Alexander Isaevich Solzhenitsyn. Curriculum vitae

Associated

I interrupt my notes again for the diary of the censor Golovanov. Only on November 14, from a conversation with the editor-in-chief of Goslitizdat A.I. Puzikov, he learned the details of the conversation between Tvardovsky and Khrushchev, which consolidated the stunning decision to publish the “camp story”. His short note is interesting in that it shows what information the censors had about us that day.

14. X.62. took place business conversation with Comrade Puzikov. Tv[ardovsky] - Khr[ushchev]

Question I: Solzhenitsyn (maybe!)

Question II: Zoshchenko (V. Kaverin). (Thinks.)

Question III: Terkin is in hell (you have to think about it). According to the cult ... (there is data).

“Two editors: me and C[ensor]. (Need to think.)

Reference

At the time of my stay at the censorship session on November 16, at about 4 pm, a courier for the journal Novy Mir arrived at the Glavlit of the USSR to arrange the publication of the magazine. No. 11 - 1962. Release to the public was allowed immediately.

3.XI.1962.

Signed for publication No. 11.

In the room:

A. Solzhenitsyn. One day of Ivan Denisovich.

Victor Nekrasov. On both sides of the ocean.

Poems by E. Mezhelaitis, S. Marshak.

Articles by K. Chukovsky (“Marshak”), V. Lakshin (“Trust”. About the stories of P. Nilin), A. Dementiev.

Reviews by M. Roshchin, I. Solovieva and V. Shitova, L. Zonina and others.

16.XI. 62- "Signal" No. 11, 1962.

20.XI. Talk about Solzhenitsyn all around. The first reviews appeared. In the evening issue of Izvestia of November 18, an article by K. Simonov, in Pravda, V. Yermilov writes that Solzhenitsyn's talent was "Tolstoy's strength."

Were with I.A. Sats in Peredelkino, visited M.A. Lifshits, had lunch with him. “In those unfree conditions that Solzhenitsyn shows,” argues Lifshitz, “free “socialist labor” became possible. If I were to write an article about this story, I would definitely remember Lenin’s “Great Initiative,” either seriously or ironically, says M.A.

“The question of the relationship between ends and means is perhaps the main question that is now occupied by everyone in the world.”

Visited these days and Marshak. After an illness, he lies in an unbuttoned white shirt, breathes heavily, rises from the pillows and talks, talks incessantly. He also talks about Solzhenitsyn, calling him either Solzhentsev or Solzhentsov (“this Solzhentsev, my dear ...”).

“In this story, the people spoke of themselves, the language is completely natural.” He also spoke about the cognitive effect of good literature - from Solzhentsev you can find out how a prisoner's day flows, what they eat and drink in the camp, etc. But this was already a little small. “Darling, why doesn’t he come to me? After all, it seems that he was at Akhmatova's? So bring him to me."

Recently, Marshak spent the whole evening telling me about Gorky: about his acquaintance with him at Stasov's dacha, about the divergence later, and about Gorky's support for their cause - the Leningrad edition of Detizdat. “Gorky knew how to charm. He sucked everything out of a person and then cooled towards him.

“Tell me what is being done in the magazine,” Marshak asked. - For a year in 1938 or 39, Tvardovsky and I dreamed of starting our own magazine. As I now understand, it was supposed to be Novy Mir… The journal must be maintained in such a way that each section of it could grow into a separate journal.”

In the next few days after the publication of No. 11, the next Plenum of the Central Committee was held. The printing house was asked for 2,200 copies of the magazine to sell it in kiosks at the Plenum.

Someone joked: “They won’t discuss the report, everyone will read Ivan Denisovich.” The excitement is terrible, the magazine is being torn out of hand, in libraries in the morning there are queues for it.

From the diary of the censor B.C. Golovanova

Materials No. 12 "New world".<…>

At about 1 o'clock in the afternoon, the editorial secretary of the magazine, Comrade Zaks, called and informed me that Comrade Polikarpov called Tvardovsky and expressed consent from the CPSU Central Committee to print an additional 25,000 copies of No. 11 of the Novy Mir magazine.

I immediately reported this to the head of the department (t?) Semenova, and she, in turn, reported to Comrade Romanov by telephone in my presence.

Then I received an explanation: “Regarding the consent of the Central Committee of the CPSU, given by Comrade Polikarpov, it is the editorial office’s business, to indicate an additional circulation of 25,000 in the imprint is also the editorial office’s business. Verification of the permission of the Central Committee of the CPSU regarding an additional circulation of 25,000 will be carried out.

All these points were explained to me by Comrade. Zaks.

Late November 1962

There was an evening at Zaks's on Aeroportovskaya Street. They sat closely in the kitchen.

Tvardovsky told me that Solzhenitsyn was with him the other day, brought new story about war. When he talked about it, he even screwed up his eyes with pleasure. Alexander Trifonovich is simply in love, he keeps saying all the time: “What a guy! He knows the price of everything. It is amazing how it is in his province that he so accurately feels what is good and what is bad in literary life. They agreed on the attitude to the latest works of Paustovsky, with whom Alexander Trifonovich is still annoyed. Trifonych was delighted that Solzhenitsyn said about “The Throw to the South” in almost the same words that he himself: “I thought it would be a civil war, battles with Wrangel, the seizure of the Crimea, but it turns out that the author rushed from Moscow to Odessa taverns and to the beaches."

Solzhenitsyn was struck by another thing - when he was at Tvardovsky's, they brought a newspaper with Simonov's article about him. He glanced briefly and said: "Well, I'll read it later, let's talk better." Alexander Trifonovich was surprised: “But how? This is the first time they write about you in a newspaper, but you seem to be not even interested in it? (Tvardovsky even saw coquetry in this.) And Solzhenitsyn: “No, they wrote about me before, in the Ryazan newspaper, when my team won the cycling championship.”

Solzhenitsyn said to Tvardovsky: “I understand that I have no time to waste. We have to take on something big."

Tvardovsky praises his new story, but does not let him read it yet. “There are some burrs there. You have to pick them up."

Paternal feeling of Alexander Trifonovich was touched by D., who met him on the stairs in the Writers' Union and asked: “Well, will you print a new story by Solzhenitsyn?” “How do you know about him?” “Solzhenitsyn has friends in Moscow,” said D.

“I thought that his main friends in Novy Mir,” lamented Alexander Trifonovich, “but it turns out that we are clampers, censors, and friends are Kopelev and company.

About L. Kopelev, whom many speak of as the discoverer of "Ivan Denisovich", Solzhenitsyn told Tvardovsky that he noticed to him, after reading the story in manuscript for the first time, about the scene of the work of prisoners - "this is in the spirit of socialist. realism." And about the second story - "A village is not worth without a righteous man": "Well, you know, this is an example of how not to write." Kopelev kept the manuscript for almost a year, not daring to hand it over to Tvardovsky. And then, after Solzhenitsyn's insistence, he handed it over to the prose department as a matter of course. “He came to me with some empty question, but he didn’t say about this, the main thing,” A.T. He was given the manuscript by A.S. Berzer.

24.XI. 1962

Alexander Trifonovich said, passing Solzhenitsyn's stories to me: “Look carefully before discussing. But by the way, you are left with small pebbles, I already threw out the cobblestones from there.

I read Tvardovsky and Solzhenitsyn's play ("Candle in the Wind") and told him: "Now you can appreciate my sincerity - I do not advise publishing the play."

"I'm thinking of talking about it with a specialist director," Solzhenitsyn replied. “But he will say “great,” Tvardovsky retorted, “he will drag you into the wheel of amendments, alterations, additions, etc.”

A stream of “camp” manuscripts poured into Novy Mir, not always high level. V. Bokov brought his poems, then some Genkin. “No matter how we have to rename our magazine to “Katorga and exile”,” I joked, and Tvardovsky repeats this joke at all intersections.

“Now everything good will come to us,” says Tvardovsky, “but even so much opportunistic turbidity, dirt is beginning to nail to Novy Mir, we need to be more careful.”

On the evening of the 24th, we feasted in the Aragvi restaurant on our victory. Raising a glass to Solzhenitsyn, Alexander Trifonovich made the next toast to Khrushchev. “In our environment it is not customary to drink for leaders, and I would feel some embarrassment if I did it just like that, out of loyal feelings. But I think everyone will agree that we now have a real reason to drink to the health of Nikita Sergeevich.

26.XI. 1962

In the morning in the editorial office a discussion of two stories by Solzhenitsyn.

Solzhenitsyn was very slow to go along with the amendments, which were proposed, however, by the members of the editorial board rather cautiously, carefully. “We have a new Marchachok,” Alexander Trifonovich was angry at his stubbornness.

The first story was universally praised. Tvardovsky suggested calling it "Matryona's Dvor" instead of "There is no village without a righteous man." “The name should not be so instructive,” Alexander Trifonovich argued.

“Yes, I have no luck with your names,” Solzhenitsyn replied, however, quite good-naturedly.

They also tried to rename the second story. Suggested - we and the author himself - "The Green Cap", "On Duty" ("Chekhov would call it that," remarked Solzhenitsyn).

Everyone agreed that in the story "The Incident at the Krechetovka Station" the motive of suspicion is improbable: the actor Tveritinov allegedly forgot that Tsaritsyn was renamed Stalingrad, and thereby ruined himself. Is it possible? Everyone knew Stalingrad.

Solzhenitsyn, defending himself, said that this was indeed the case. He himself remembers these stations, near the military rear, when he served in the wagon train at the beginning of the war. But there was material, material - and the case with the artist, whom he learned about, illuminated everything for him.

I reproached Solzhenitsyn for certain excesses of literature, the arbitrary use of old words, such as "shoulder", "zelo". And artificial - "venulo", "menelo". “You want to straighten me out,” he fumed at first. Then he agreed that some phrases are unsuccessful. - I was in a hurry with this story, but in general I like forgotten words. In the camp, I came across the third volume of Dahl's dictionary, I went through it, correcting my Rostov-Taganrog language.

Talking with me later in private, he was so generous with his generosity that he even offered a compliment: "And you have an ear for words."

I told him about the meeting with Y. Stein. “I have common acquaintances with everyone,” Alexander Isaevich replied, “even with Khrushchev. I was in the same cell with his personal driver in 1945. He spoke well of Nikita. And now people began to appear who recognized themselves in the story. Katorang Buinovsky is Burkovsky, he serves in Leningrad. The head of the Special Camp described in "Ivan Denisovich" works as a watchman in "Gastronom". He complains that he is offended, comes to his former prisoners with a quarter - to talk about life.

He was found in Ryazan and K., who introduced himself to him as the son of a repressed man. I knew him from university.

"What kind of person is he?" Solzhenitsyn asked. I said that I was thinking about him, and I was going to confirm this with some episode, but Alexander Isaevich interrupted me: “Enough. It is important for me to know your opinion. Do not need anything else".

He speaks quickly, briefly, as if continuously saving time on conversation.

28.XI. 1962

Tvardovsky was ironic about the response to Solzhenitsyn's story that appeared in Literature and Life.

“This breathless newspaper published a review of Dymshits, written as if on purpose so as to ward off the story ... Not a single vivid quote, not a reminder of any scene ... Compares with Dostoevsky's House of the Dead, and then out of place. After all, with Dostoevsky it’s the other way around: there the exiled intellectual looks at the life of simple guarded people, but here everything is through the eyes of Ivan Denisovich, who, in his own way, sees the intellectual (Caesar Markovich).

“And as Tyurin in Solzhenitsyn says exactly this: after all, the 37th year is retribution for the expropriation of the peasantry in the 30th.” And Alexander Trifonovich recalled his father: “What kind of fist is he? Unless the house is a five-wall. But I was threatened with expulsion from the party for concealing the facts of my biography - the son of a kulak, exiled to the Urals.

From the book 70 and another 5 years in the ranks author Ashkenazi Alexander Evseevich9. Passing reading While I am writing all this in fits and starts, I continue to read everything that comes up. I decided to insert this part of the “Triptych” by Yakov Kozlovsky both in the “Personnel” section and in the “Peter I” section. flags in

From the book Solzhenitsyn and the wheel of history author Lakshin Vladimir YakovlevichDiaries and Passing

From the author's bookPassing In September 1962, I was not in the editorial office. Meanwhile, events developed as follows: between 9 and 14 September B.C. Lebedev in the south read aloud the story of Solzhenitsyn N.S. Khrushchev and A.I. Mikoyan. September 15 (or 16) - called Tvardovsky at home with the news that the story of Khrushchev

From the author's bookIn passing I will interrupt the diary for a later note. In the 1970s, one of the heirs of Viktor Sergeevich Golovanov, the censor of Novy Mir, handed me a notebook left over from the deceased. On the cover it says: “Notebook 1. Passage of materials on the magazine "New World" with

From the author's bookIn passing I interrupt my notes again for the sake of the diary of the censor Golovanov. Only on November 14, from a conversation with the editor-in-chief of Goslitizdat A.I. Puzikov, he learned the details of Tvardovsky's conversation with Khrushchev, which consolidated the stunning decision - to publish the "camp

From the author's bookIn passing We were still living in euphoria from the success of One Day, and censorship was still wary of us after what had happened. But in early December, N.S. Khrushchev unexpectedly visited the exhibition of the Moscow Union of Artists in the Manege. Incited by V.A. Serov and other leaders of the Union of Artists, and perhaps

From the author's bookIn passing In the evening issue of Izvestia 29. III. 1963 published an article by V. Poltoratsky "Matryona Dvor and its environs" - the first, apart from Kozhevnikov's review, a response to Solzhenitsyn's story.6. IV. 1963<…>We made an insert in the front line for No. 4 - about "Matryona Dvor". Censorship

From the author's bookPassing In fact, the number was released only at the end of January. The date 29.XP.63, apparently, was given not according to the last, but according to the first sheet signed for printing. The censorship continued to do so, in accordance with a special instruction, in order to disorient those readers, here and in the West,

From the author's bookAssociated<…>A.I. Todorsky, glorified in his book, had a difficult fate. Lenin spoke about his pamphlet A Year with a Rifle and a Plow in 1920. Leaving the camp, Todorsky, himself a retired lieutenant general, spent useful work- wrote something that was not published anywhere then

From the author's bookPassing At first glance, the article in Literaturnaya Gazeta had no mood or mood. Praise for "meticulous quoting" and, a few paragraphs later, reproach the critic for "truncation of citations"; call themselves defenders of the story and its hero - and at the same time express dissatisfaction

From the author's bookPassing I didn't write it down in my diary, but I remember that evening distinctly. Busy with Ehrenburg's stories, I jumped out late, caught a taxi with difficulty and rushed to Zhuravlev Square, to the television theater, where I promised to be an hour before the start. The fact is that the transfer, as in those

From the author's bookA year later, I read M. Mikhailov’s essays “Moscow, 1964”, published in many countries, from which, it seems, his misadventures began: his trial, years in prison, then emigration to the West. In Mikhailov’s essays, a special chapter was devoted to our conversation . He passed

From the author's bookIn passing The end of 1964 and the beginning of 1965 were marked for us by troubles around Tvardovsky's article "On the occasion of the anniversary", prepared for the opening of the 1st issue. In January, the magazine, founded in 1925, turned 40 years old.<…>Censorship marks in the article “On the occasion

At one time, M. Gorky very accurately described the inconsistency of the character of a Russian person: “Piebald people are good and bad together.” In many ways, this "piebaldness" became the subject of research by Solzhenitsyn.

The protagonist of the story “The Incident at the Kochetonka Station” (1962), a young lieutenant Vasya Zotov, embodies the kindest human traits: intelligence, openness towards a front-line soldier or encirclement who entered the room of the linear commandant’s office, a sincere desire to help in any situation. Two female images, only slightly outlined by the writer, set off the deep purity of Zotov, and even the very thought of betraying his wife, who was in occupation under the Germans, is impossible for him.

The compositional center of the story is Zotov's meeting with his entourage lagging behind his echelon, which strikes him with its intelligence and gentleness. Everything - the words, the intonations of the voice, the gentle gestures of this man, who is capable of holding on with dignity and gentleness even in the monstrous flaw put on him - attracts the hero: he “was extremely pleased with his manner of speaking; his manner of stopping if it seemed that the interlocutor wanted to object; his manner of not waving his arms, but somehow light movements fingers to explain their speech. He reveals to him his half-childish dreams of escaping to Spain, talks about his longing for the front and looks forward to several hours of wonderful communication with an intelligent, cultured and knowledgeable person- an actor before the war, a militia without a rifle - at its beginning, a recent entourage who miraculously got out of the German “cauldron” and now lagged behind his train - without documents, with a meaningless follow-up sheet, in essence, and not a document. And here the author shows the struggle of two principles in the soul of Zotov: human and inhuman, evil, suspicious. Already after a spark of understanding ran between Zotov and Tveritinov, which once arose between Marshal Davout and Pierre Bezukhov, which then saved Pierre from execution, a circular appears in Zotov’s mind, crossing out the sympathy and trust that arose between two hearts that had not yet had time to stand still on war. “The lieutenant put on his glasses and again looked at the catch-up list. The follow-up sheet, in fact, was not a real document, it was drawn up from the words of the applicant and could contain the truth, or it could also be a lie. The instruction demanded to be extremely attentive to the encircled, and even more so to the loners. And Tveritinov’s accidental slip of the tongue (he only asks what Stalingrad used to be called) turns into disbelief in Zotov’s young and pure soul, already poisoned by the poison of suspicion: “And - everything broke off and went cold in Zotov<...>. So, not an encirclement. Sent! Agent! Probably a white émigré, that’s why the manners are like that.” What saved Pierre did not save the unfortunate and helpless Tveritinov - a young lieutenant "surrenders" a man who has just fallen in love and is so sincerely interested in him in the NKVD, and last words Tveritinova: “What are you doing! What are you doing!<...>You can't fix this!!" - are confirmed by the last, accordant, as always with Solzhenitsyn, phrase: "But never later in his whole life Zotov could not forget this man ...".

Naive kindness and cruel suspicion - two qualities that seem to be incompatible, but quite conditioned Soviet era 30s, - are combined in the soul of the hero.

The inconsistency of character appears sometimes from the comic side - as in the story "Zakhar-Kalita" (1965).

This short story is built entirely on contradictions, and in this sense it is very characteristic of the writer's poetics. Its deliberately lightened beginning, as it were, parodies the common motifs of the confessional or lyrical prose of the 60s, which clearly simplify the problem of the national character.

“My friends, are you asking me to tell you something from the summer cycling?” - this opening, setting you up for something summer, vacation and optional, contrasts with the content of the story itself, where a picture of the September battle of 1380 is recreated on several pages. “Starting, look at the turning point in Russian history, burdened with historiographic solemnity: “The truth of history is bitter, but it is easier to express it than hide it: not only the Circassians and Genoese were brought by Mamai, not only the Lithuanians were in alliance with him, but also the Prince of Ryazan Oleg.<...>For this, the Russians crossed the Don, in order to protect their backs with the Don from their own, from the Ryazan people: they would not hit, the Orthodox. The contradictions lurking in the soul of one person are also characteristic of the nation as a whole: “Was it not from here that the fate of Russia was led? Isn't there a turning point in her story here? Is it always only through Smolensk and Kyiv that enemies swarmed at us?..” Thus, from the inconsistency of the national consciousness, Solzhenitsyn takes a step towards the study of the inconsistency of national life, which led much later to other turns in Russian history.

But if the narrator can pose such questions and comprehend them, then the main character of the story, the self-appointed watchman of the Kulikovo field Zakhar-Kalita, simply embodies an almost instinctive desire to preserve the historical memory that was lost. There is no sense in his constant, day and night stay on the field, but the very fact of the existence of a funny eccentric person is significant for Solzhenitsyn. Before describing it, he seems to stop in bewilderment and even strays into sentimental, almost Karamzin intonations, begins the phrase with such a characteristic interjection “ah”, and ends with question and exclamation marks.

On the one hand, the Superintendent of the Kulikovo Field with his senseless activities is ridiculous, how ridiculous his intentions are to reach Furtseva, the then Minister of Culture, in search of his own, only known truth. The narrator cannot help laughing, comparing him with a dead warrior, next to whom, however, there is neither a sword nor a shield, but instead of a helmet, a cap worn out and near his arm a bag with selected bottles. On the other hand, the completely disinterested and senseless, it would seem, devotion to Paul as the visible embodiment of Russian history makes us see something real in this figure - sorrow. The author's position is not clear - Solzhenitsyn, as it were, is balancing on the verge of the comic and the serious, seeing one of the bizarre and extraordinary forms of the Russian national character. Comic for all the senselessness of his life on the Field (the heroes even have a suspicion that in this way Zakhar-Kalita shirks hard rural work) is a claim to seriousness and his own importance, his complaints that he, the field's caretaker, is not given weapons. And next to this - it’s not at all the comic passion of the hero, using the means available to him, to testify to the historical glory of Russian weapons. And then “everything that mocking and condescending thing that we thought about him yesterday immediately fell away. On this frosty morning, rising from the shock, he was no longer the Overseer, but, as it were, the Spirit of this Field, guarding, never leaving him.

Of course, the distance between the narrator and the hero is enormous: the hero does not have access to the historical material with which the narrator freely operates, they belong to different cultural and social environments, but they are brought together by a true devotion to national history and culture, belonging to which makes it possible to overcome social and cultural differences.

Turning to the folk character in the stories published in the first half of the 60s, Solzhenitsyn offers literature a new concept of personality. His heroes, such as Matryona, Ivan Denisovich (the image of the janitor Spiridon from the novel “In the First Circle” also gravitates towards them), are people who do not reflect, they live by some natural, as if given from the outside, in advance and not developed by them ideas. And, following these ideas, it is important to survive physically in conditions that are not at all conducive to physical survival, but not at the cost of losing one's own human dignity. To lose it means to perish, i.e., having physically survived, to cease to be a person, to lose not only the respect of others, but also respect for oneself, which is tantamount to death. Explaining this, relatively speaking, ethics of survival, Shukhov recalls the words of his first brigadier Kuzemin: “Here’s who dies in the camp: who licks bowls, who hopes for the medical unit, and who goes to knock on a godfather.”

With the image of Ivan Denisovich, a new ethics, as it were, came into literature, forged in the camps through which a very large part of society passed. (Many pages of The Gulag Archipelago will be devoted to the study of this ethics.) Shukhov, not wanting to lose his human dignity, is not at all inclined to take all the blows of camp life - otherwise he simply cannot survive. “That's right, groan and rot,” he remarks. “And if you resist, you will break.” In this sense, the writer denies the generally accepted romantic ideas about the proud confrontation of personality tragic circumstances on which literature brought up the generation of Soviet people of the 30s. And in this sense, the opposition of Shukhov and the captain Buinovsky, the hero who takes the blow, is interesting, but often, as it seems to Ivan Denisovich, it is senseless and destructive for himself. The protests of the captain rank against the morning search in the cold of people who had just woken up after getting up, shivering from the cold, are naive:

“Buinovsky - in the throat, he got used to his destroyers, but there are no three months in the camp:

You have no right to undress people in the cold! You don't know the ninth article of the criminal code!..

Have. They know. You, brother, don't know yet."

The purely folk, peasant practicality of Ivan Denisovich helps him survive and preserve himself as a man - without setting himself eternal questions, without trying to generalize the experience of his military and camp life, where he ended up after captivity (neither the investigator who interrogated Shukhov, nor he himself were able to figure out what kind of task of German intelligence he was performing). He, of course, cannot reach the level of historical-philosophical generalization of the camp experience as a facet of the national-historical existence of the 20th century, which Solzhenitsyn himself will rise to in The Gulag Archipelago.

In the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”, Solzhenitsyn faces the creative task of combining two points of view - the author and the hero, points of view that are not opposite, but ideologically similar, but differ in the level of generalization and breadth of material. This task is solved almost exclusively by stylistic means, when there is a slightly noticeable gap between the speech of the author and the character, either increasing or practically disappearing.

Solzhenitsyn refers to the tale style of narration, which gives Ivan Denisovich the opportunity for verbal self-realization, but this is not a direct tale that reproduces the hero’s speech, but introduces the image of the narrator, whose position is close to that of the hero. Such a narrative form made it possible at some moments to distance the author and the hero, to make a direct conclusion of the narration from the “author's Shukhov's” into the “author's Solzhenitsyn's” speech... By shifting the boundaries of Shukhov's sense of life, the author received the right to see what his hero could not see , something that is beyond Shukhov's competence, while the ratio of the author's speech plan to the plan of the hero can be shifted in the opposite direction - their points of view and their stylistic masks will immediately coincide. Thus, “the syntactic and stylistic structure of the story has developed as a result of a peculiar use of adjacent possibilities of a tale, shifts from improperly direct to improperly authorial speech,” which are equally focused on the colloquial features of the Russian language.

Both the hero and the narrator (here is the obvious basis for their unity, expressed in the speech element of the work) have access to that specifically Russian view of reality, which is usually called folk. It is precisely the experience of a purely "muzhik" perception of the camp as one of the aspects of Russian life in the 20th century. and paved the way for the story to the reader of the "New World" and the whole country. Solzhenitsyn himself recalled this in The Calf:

“I won’t say that such an exact plan, but I had a sure hunch-premonition: this peasant Ivan Denisovich cannot remain indifferent to the upper peasant Alexander Tvardovsky and the riding peasant Nikita Khrushchev. And so it came true: not even poetry, not even politics, decided the fate of my story, but this is his ultimate peasant essence, so much ridiculed, trampled and cursed with us since the Great Break, and even earlier” (p. 27).

In the stories published at that time, Solzhenitsyn did not approach one of the most important topics for him - the topic of resistance to the anti-people regime. It will become one of the most important in the Gulag Archipelago. So far, the writer was interested in the folk character itself and its existence “in the very interior of Russia - if there was such a place, she lived”, in that very Russia that the narrator is looking for in the story “Matryona Dvor”. Ho, he finds untouched by the turmoil of the 20th century. an island of natural Russian life, but a folk character that managed to preserve itself in this turmoil. “There are such born angels,” the writer wrote in the article “Repentance and Self-Restriction”, as if characterizing Matryona, “they seem to be weightless, they seem to glide over this slurry, not drowning in it at all, even touching its surface with their feet? Each of us met such people, there are not ten or a hundred of them in Russia, they are the righteous, we saw them, were surprised (“eccentrics”), used their good, in good moments answered them the same, they dispose, - and immediately sank again to our doomed depth” (Publicism, vol. 1, p. 61). What is the essence of Matrona's righteousness? In life, not by lies, we will now say in the words of the writer himself, uttered much later. She is outside the sphere of the heroic or exceptional, she realizes herself in the most ordinary, everyday situation, she experiences all the “charms” of the Soviet rural novelty of the 50s: having worked all her life, she is forced to bother about a pension not for herself, but for husband, missing since the beginning of the war, measuring kilometers on foot and bowing to office tables. Not being able to buy peat, which is mined everywhere around, but not sold to collective farmers, she, like all her friends, is forced to take it secretly. Creating this character, Solzhenitsyn places him in the most ordinary circumstances of rural collective farm life in the 1950s. with its lack of rights and arrogant disregard for an ordinary, unimportant person. The righteousness of Matrena lies in her ability to preserve her humanness even in such inaccessible conditions for this.

But who does Matryona oppose, in other words, in a collision with what forces does her essence manifest itself? In a collision with Thaddeus, a black old man who appeared before the narrator, the school teacher and Matryona's tenant, on the threshold of her hut, when he came with a humiliated request for his grandson? He crossed this threshold forty years ago, with fury in his heart and with an ax in his hands - his bride from the war did not wait, she married her brother. “I stood on the threshold,” says Matryona. - I'll scream! I would throw myself at his knees! It’s impossible ... Well, he says, if it weren’t for my brother, I would chop you both!”

According to some researchers, the story "Matryona's Dvor" is latently mystical.

Already at the very end of the story, after the death of Matryona, Solzhenitsyn lists her quiet virtues:

“Not understood and abandoned even by her husband, who buried six children, but did not like her sociable, a stranger to her sisters, sister-in-law, funny, stupidly working for others for free - she did not accumulate property to death. Dirty white goat, rickety cat, ficuses...

We all lived next to her and did not understand that she was the same ethnographer, without whom, according to the proverb, the village does not exist.

Neither city.

Not all our land."

And the dramatic finale of the story (Matryona dies under a train, helping to transport Thaddeus the logs of her own hut) gives the ending a very special, symbolic meaning: she is no more, therefore, the village cannot exist without her? And the city? And all our land?

In 1995-1999 Solzhenitsyn published new stories, which he called "two-part". Their most important compositional principle is the opposition of two parts, which makes it possible to compare two human destinies and characters that manifested themselves differently in the general context of historical circumstances. Their heroes - and people who seem to have sunk into the abyss of Russian history and left a bright mark in it, such as, for example, Marshal G.K. Zhukov - are considered by the writer from a purely personal side, regardless of official regalia, if any are available. The problematic of these stories is formed by the conflict between history and a private person. The ways of resolving this conflict, no matter how different they may seem, always lead to the same result: a person who has lost faith and is disoriented in historical space, a person who does not know how to sacrifice himself and compromises, is crushed and crushed by the terrible era in which he live.

Pavel Vasilievich Ektov is a rural intellectual who saw the meaning of his life in serving the people, confident that “everyday assistance to the peasant in his current urgent needs, alleviation of the people’s need in any real form does not require any justification.” During the Civil War, Ektov did not see for himself, a populist and a people-lover, any other way out but to join the peasant insurrectionary movement led by Ataman Antonov. Most educated person among Antonov's associates, Ektov became his chief of staff. Solzhenitsyn shows a tragic zigzag in the fate of this generous and honest man, who inherited from the Russian intelligentsia an inescapable moral need to serve the people, to share the peasant's pain. But issued by the same peasants (“on the second night he was extradited to the Chekists at the denunciation of a neighbor woman”), Ektov is broken by blackmail: he cannot find the strength to sacrifice his wife and daughter and commits a terrible crime, in fact, “surrendering” all the Antonov headquarters - those people to whom he himself came to share their pain, with whom he needed to be in hard times, so as not to hide in his mink in Tambov and not to despise himself! Solzhenitsyn shows the fate of a crushed man who finds himself in front of an insoluble life equation and is not ready to solve it. He can put his life on the altar, but the life of his daughter and wife?.. Is it even possible for a person to do such a thing? "The Bolsheviks used a great lever: to take families hostage."

The conditions are such that the virtuous qualities of a person turn against him. A bloody civil war squeezes a private person between two millstones, grinding his life, his fate, his family, his moral convictions.

“Sacrifice his wife and Marinka (daughter. - M.G.), step over them - how could he ??

For whom else in the world - or for what else in the world? - is he more responsible than for them?

Yes, all the fullness of life - and they were.

And most - to hand over them? Who can?!”

The situation appears to the ego as hopeless. The non-religious and humanistic tradition, dating back to the Renaissance and directly denied by Solzhenitsyn in his Harvard speech, prevents a person from feeling his responsibility more than for his family. “In the story “Ego,” the modern researcher P. Spivakovsky believes, “it is precisely shown how the non-religious and humanistic consciousness of the protagonist turns out to be a source of betrayal.” The hero's inattention to the sermons of rural priests is very feature worldview of the Russian intellectual, to which Solzhenitsyn, as if in passing, draws attention. After all, Ektov is a supporter of “real”, material, practical activity, but focusing only on it alone, alas, leads to oblivion of the spiritual meaning of life. Perhaps the church sermon, which the Ego arrogantly refuses, could be the source of “that very real help, without which the hero falls into the trap of his own worldview”, that very humanistic, non-religious one, which does not allow the individual to feel his responsibility before God, but his own fate - as part of God's providence.

A man in the face of inhuman circumstances, changed, crushed by them, unable to refuse compromise and deprived of a Christian worldview, defenseless in the face of the conditions of a forced bargain (can the Ego be judged for this?) is another typical situation in our history.

Ego was compromised by two features of the Russian intellectual: belonging to a non-religious humanism and following the revolutionary democratic tradition. But, paradoxically, the writer saw similar collisions in Zhukov's life (the story "On the Edge", a two-part composition paired with "Ego"). The connection between his fate and the fate of Ego is amazing - both fought on the same front, only on different sides of it: Zhukov - on the side of the Reds, Ego - the rebellious peasants. And Zhukov was wounded in this war with his own people, but, unlike the idealist Ego, he survived. In his history, full of ups and downs, in victories over the Germans and in painful defeats in apparatus games with Khrushchev, in the betrayal of people whom he once saved (Khrushchev - twice, Konev from the Stalinist tribunal in 1941), in the fearlessness of youth, Solzhenitsyn is trying to find the key to understanding this fate, the fate of the marshal, one of those Russian soldiers who, according to I. Brodsky, “boldly entered foreign capitals, / but returned in fear to their own” (“ On the death of Zhukov”, 1974). In the ups and downs, he sees a weakness behind the marshal's iron will, which manifested itself in a completely human tendency to compromise. And here is the continuation of the most important theme of Solzhenitsyn's work, begun in One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and culminating in The Gulag Archipelago: this theme is connected with the study of the boundary of compromise, which a person who wants not to lose himself must know. Crushed by heart attacks and strokes, senile infirmity, Zhukov appears at the end of the story - but this is not his trouble, but in another compromise (he inserted two or three phrases into the book of memoirs about the role of political instructor Brezhnev in the victory), which he went to see his own book published. Compromise and indecision in the turning periods of life, the very fear that he experienced when returning to his capital, broke and finished off the marshal - differently than Ego, but in essence the same. The ego is helpless to change anything, when it betrays terribly and cruelly, Zhukov, too, can only helplessly look back at the edge of life: “Maybe even then, even then - it was necessary to decide? Oh, it seems - a fool, a fool? praying for his idol Tukhachevsky, he participated in the destruction of the world of the Russian village that gave birth to him, when the peasants were smoked out of the forests with gases, and the “probanditized” villages were burned completely.

The stories about Ektov and Zhukov are addressed to the fates of subjectively honest people, broken by the terrible historical circumstances of the Soviet era. Ho, another variant of compromise with reality is also possible - complete and joyful submission to it and the natural oblivion of any pangs of conscience. About this story "Apricot jam". The first part of this story is a terrible letter addressed to a living classic Soviet literature. It is written by a semi-literate person who is quite clearly aware of the hopelessness of the Soviet life vice, from which he, the son of dispossessed parents, will no longer get out, having disappeared in labor camps:

“I am a slave in extreme circumstances, and such a life has set me up to the last insult. Maybe it will be inexpensive for you to send me a grocery parcel? Have mercy...”

The food package contains, perhaps, the salvation of this man, Fyodor Ivanovich, who has become just a unit of the forced Soviet labor army, a unit whose life has no significant value at all. The second part of the story is a description of the life of a beautiful cottage famous writer, rich, warmed and caressed at the very top, - a man happy from a successfully found compromise with the authorities, joyfully lying both in journalism and in literature. The Writer and the Critic, who carry on literary official conversations over tea, are in a different world than the entire Soviet country. The voice of the letter with the words of truth that has flown into this world of rich writers' dachas cannot be heard by representatives of the literary elite: deafness is one of the conditions for a compromise with the authorities. The rapture of the Writer about the fact that “from the depths of modern readers emerges a letter with a primordial language is the height of cynicism.<...>what a self-willed, and at the same time captivating combination and control of words! Enviable and writer!” A letter that appeals to the conscience of a Russian writer (according to Solzhenitsyn, the hero of his story is not a Russian, but a Soviet writer), becomes only material for the study of non-standard speech turns that help stylization folk speech, which is comprehended as exotic and to be reproduced by the "folk" Writer, as if knowing the national life from the inside. The highest degree of disdain for the cry of a tortured person in the letter is visible in the writer's remark, when he is asked about the connection with the correspondent: “Yes, what to answer, the answer is not the point. It's a matter of language."

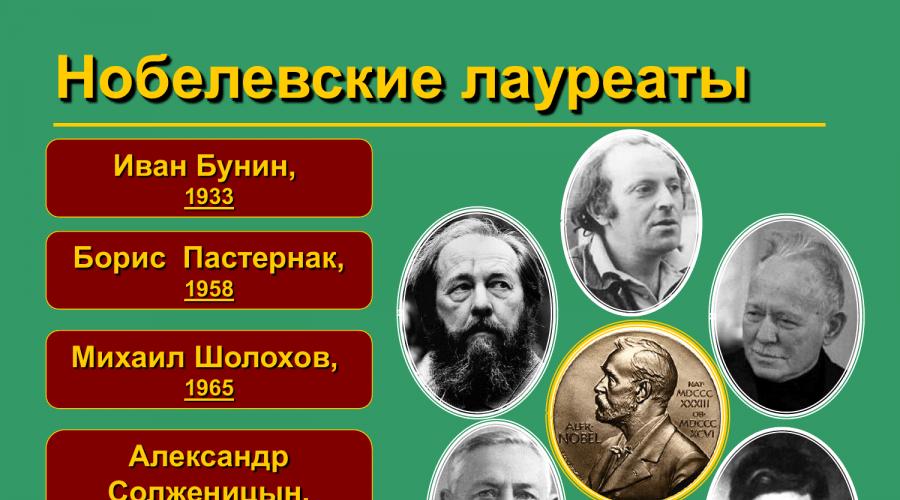

With this article, we open a series of articles dedicated to the Nobel Prize winners from Russia in the field of literature. We are interested in the question - for what, why and by what criteria are issued this award, as well as why this award is not given to people who deserve it with their talent and achievements, for example, Leo Tolstoy and Dmitry Mendeleev.

Laureates of the Nobel Prize in Literature from our country in different years steel: I. Bunin, B. Pasternak, M. Sholokhov, A. Solzhenitsyn, I. Brodsky. At the same time, it should be noted that, with the exception of M. Sholokhov, all the rest were emigrants and dissidents.

In this article, we will talk about the 1970 Nobel Prize winner writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

WHO IS ALEXANDER SOLZHENITSYN?

Alexander Solzhenitsyn is known to the reader for his works “In the First Circle”, “Gulag Archipelago”, “Cancer Ward”, “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” and others.

And this writer appeared on our heads, thanks to Khrushchev, for whom Solzhenitsyn (even the word “lie” is present in the surname itself) became another tool for cracking down on the Stalinist past, and no more.

The pioneer of the “artistic” lies about Stalin (with the personal support of Khrushchev) was the former camp informer Solzhenitsyn, elevated to the rank of Nobel laureate in literature (see the article “Vetrov, aka Solzhenitsyn” in the Military History Journal, 1990, No. 12 , p. 77), whose books were published in mass editions during the period of “perestroika” at the direction of the treacherous leadership of the country in order to destroy the USSR.

Here is what Khrushchev himself writes in his memoirs:

I am proud that at one time I supported one of Solzhenitsyn's first works... I don't remember Solzhenitsyn's biography. I was told earlier that he spent a long time in the camps. In the mentioned story, he proceeded from his own observations. I read it. It leaves a heavy impression, exciting, but true. And most importantly, it causes disgust for what was happening under Stalin .... Stalin was a criminal, and criminals must be condemned at least morally. The strongest judgment is to brand them in a work of art. Why, on the contrary, was Solzhenitsyn considered a criminal?

Why? Because the anti-Soviet graphomaniac Solzhenitsyn turned out to be a rare find for the West, who was rushed in 1970 (even though given year was not chosen by chance - the year of the 100th anniversary of the birth of V.I. Lenin, as another attack on the USSR) to undeservedly award the Nobel Prize in Literature to the author of "Ivan Denisovich" is an unprecedented fact. As Alexander Shabalov writes in Comrade Stalin's Eleventh Strike, Solzhenitsyn begged for the Nobel Prize, stating:

I need this award as a step in a position, in a battle! And the faster I get it, the harder I will become, the harder I will hit!

And, indeed, the name of Solzhenitsyn became the banner of the dissident movement in the USSR, which at one time played a huge negative role in the elimination of the Soviet socialist system. And most of his opuses first saw the light "over the hill" with the support of Radio Liberty, the Russian department of the BBC, the Voice of America, Deutsche Welle, the Russian department of the State Department, the Pentagon's agitation and propaganda department, and the information department of the British MI.

And having done his dirty deed, he was sent back to Russia destroyed by the liberals. Because even enemies do not need such traitors. Where he grumbled with the air of a "prophet" on Russian television with his "dissenting" opinion of the mafia Yeltsin regime, which no longer interested anyone and could change absolutely nothing.

Let us consider in more detail the biography, creativity, ideological views writer A. Solzhenitsyn.

SHORT BIOGRAPHY

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was born on December 11, 1918 in Kislovodsk, into a Cossack family. Father, Isaakiy (that is, in fact, his patronymic is Isaakovich, that is, he lied to everyone, saying everywhere, including in writing, that he was Isaevich) Semenovich, died on a hunt six months before the birth of his son. Mother - Taisiya Zakharovna Shcherbak - from a family of a wealthy landowner.

In 1939, Solzhenitsyn entered the correspondence department of the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature, and History (some sources indicate literary courses at Moscow State University). In 1941 Alexander Solzhenitsyn graduated from the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Rostov University (entered in 1936).

In October 1941 he was drafted into the army, and in 1942, after studying at the artillery school in Kostroma, he was sent to the front as the commander of a sound reconnaissance battery. He was awarded the Order of the Patriotic War 2nd class and the Order of the Red Star.

The book written by Solzhenitsyn's first wife, Natalia Reshetovskaya, published in the Soviet Union, contains funny things: it turns out that in 1944-1945, Solzhenitsyn, being a Soviet officer, composed plans for the elimination of Stalin.

At the same time, he wrote his directives in letters and sent them to his friends. So he wrote directly - “Directive number one”, etc., and this is obvious madness, because then there was military censorship and every letter was stamped “Checked by military censorship”. For such letters then, in wartime, they were guaranteed to be arrested, and therefore only a half-mad person, or a person who hopes that the letter will be read and sent from the front to the rear, could do such things. And these are not simple words.

The fact is that among the artillery batteries during the Great Patriotic War there were also batteries of instrumental reconnaissance - sound measurements, on one of which Solzhenitsyn served. This was the most reliable means of detecting enemy firing batteries. Sound meters deployed a system of microphones on the ground that received an acoustic wave from a shot, the signal was recorded and calculated, on the basis of which they received the coordinates of the enemy’s firing batteries even in a battlefield that was fairly saturated with artillery. This made it possible, with a good organization of command and control, to begin to suppress enemy batteries with their artillery fire after one or three volleys of the enemy.

Therefore, sound meters were valued, and in order to ensure the safety of their combat work, they were deployed in the near rear, and not on the front lines, and even more so not in the first line of trenches. They were placed so that they did not end up near objects that could be subjected to enemy air raids and shelling. During the retreat, they were among the first to be taken out of the battle area; during the offensive, they followed the troops of the first line. Those. doing their important work, they directly came into contact with the enemy in a combat situation only in some emergency cases, and to counter it they had only small arms - carbines and personal weapons of officers.

However, A.I. Solzhenitsyn was "lucky": the Germans hit him, the front rolled back, command and control of the troops was lost for some time - an opportunity presented itself to show heroism. But it was not he who showed heroism, but the foreman of the battery, who saved it by leading it to the rear. War is paradoxical. If we talk specifically about the sound-measuring battery, then the actions of the foreman were correct: he saved equipment and qualified personnel from useless death in battle, for which the sound-measuring battery was not intended. Why didn’t its commander Solzhenitsyn, who appeared at the location of the battery later, do this, is an open question: “the war wrote off” (it was not up to such trifles).

But this episode was enough for A.I. Solzhenitsyn: he realized that in the war for socialism alien to him (he himself came from a clan of not the last rich people in Russia, although not from the main branch: uncle on the eve of World War I owned one of the nine Rolls - Royces" that existed in the empire) can be killed, and then the "idea fix" - a dream from childhood: to enter the history of world literature as Dostoevsky or Tolstoy of the 20th century, will not come true. So A.I. Solzhenitsyn fled from the front to the Gulag in order to be guaranteed to survive. And the fact that he laid a friend down is trifles against the background of salvation precious life future "great writer". On February 9, 1945, he was arrested and on July 27 was sentenced to 8 years in labor camps.

Natalya Reshetovskaya further describes Solzhenitsyn's arrest, where she was interrogated as a witness and other people were also interrogated. One of the witnesses, a sailor, a young midshipman, testified that Solzhenitsyn met him by chance on the train and immediately began to engage in anti-Stalinist agitation. To the question of the investigator - “why didn’t you immediately report it?” The midshipman replied that he immediately realized that he was in front of a madman. That's why he didn't deliver.

He stayed in the camps from 1945 to 1953: in New Jerusalem near Moscow; in the so-called "sharashka" - a secret research institute in the village of Marfino near Moscow; in 1950 - 1953 he was imprisoned in one of the Kazakh camps.

In February 1953 he was released without the right to reside in the European part of the USSR and sent to the "eternal settlement" (1953 - 1956); lived in the village of Kok-Terek, Dzhambul region (Kazakhstan).

On February 3, 1956, by decision of the Supreme Court of the USSR, Alexander Solzhenitsyn was rehabilitated and moved to Ryazan. Worked as a mathematics teacher.

In 1962, in the journal Novy Mir, by special permission of N.S. Khrushchev (!!!, which says a lot), the first story by Alexander Solzhenitsyn was published - “One day in the life of Ivan Denisovich” (reworked at the request of the editorial story “ Shch-854. One day for one convict). The story was nominated for the Lenin Prize, which caused active resistance from the communist authorities.

In 1964, the ideological inspirer and patron of A. Solzhenitsyn, Nikita Khrushchev, was removed from power, after which Solzhenitsyn's "star" in the USSR began to fade.

In September 1965, the so-called archive of Solzhenitsyn fell into the State Security Committee (KGB) and, by order of the authorities, further publication of his works in the USSR was discontinued: already published works were withdrawn from libraries, and new books began to be published through the channels of "samizdat" and abroad .

In November 1969 Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Writers' Union. In 1970, Alexander Isaevich Solzhenitsyn won the Nobel Prize in Literature, but refused to travel to Stockholm for the award ceremony, fearing that the authorities would not let him back to the USSR. In 1974, after the publication of the book “The Gulag Archipelago” in Paris (in the USSR, one of the manuscripts was confiscated by the KGB in September 1973, and in December 1973 a publication took place in Paris, which leads to interesting thoughts, given the fact that the head of the KGB at that time was Yu.V. Andropov, about whom we wrote in this article - http://inance.ru/2015/06/andropov/), the dissident writer was arrested. On February 12, 1974, a trial took place: Alexander Solzhenitsyn was found guilty of high treason, deprived of citizenship and sentenced to expulsion from the USSR the next day.

From 1974 Solzhenitsyn lived in Germany, in Switzerland (Zurich), from 1976 - in the USA (near the city of Cavendish, Vermont). Despite the fact that Solzhenitsyn lived in the United States for about 20 years, he did not ask for American citizenship. He rarely spoke with representatives of the press and the public, which is why he was known as a "Vermont recluse." He criticized both the Soviet order and American reality. During 20 years of emigration in Germany, the USA and France, he published a large number of works.

In the USSR, Solzhenitsyn's works began to be published only from the end of the 1980s. In 1989, in the same Novy Mir magazine, where One Day ... was published, the first official publication of excerpts from the novel The Gulag Archipelago took place. On August 16, 1990, by decree of the President of the USSR, the Soviet citizenship of Alexander Isaevich (?) Solzhenitsyn was restored. In 1990, for the book The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn was awarded the State Prize (of course, presented by liberals who hate Soviet power). May 27, 1994 the writer returned to Russia. In 1997 he was elected a full member of the Academy of Sciences of the Russian Federation.

WHO ARE YOU, ALEXANDER SOLZHENITSYN - A "GREAT WRITER" OR A "GREAT TRAITOR" OF OUR MOTHERLAND?

The name of Alexander Solzhenitsyn has always caused a lot of heated debate and discussion. Some call and called him a great Russian writer and active social activist, others - a fraudster historical facts and detractor of the Motherland. However, the truth is probably somewhere. The casket opens very simply: Khrushchev needed a hack who, without a twinge of conscience, could denigrate the successes that were achieved during the reign of Joseph Stalin. And it turned out to be Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

For almost 20 years, Russian liberal ministers and officials openly called Solzhenitsyn a great Russian writer. And even for decency, he never once objected to this. Equally, he did not protest against the titles "Leo Tolstoy of the 20th century" and "Dostoevsky of the 20th century." Alexander Isaevich modestly called himself "Antilenin".

True, the true title of "great writer" in Russia was given only by Time. And, apparently, Time has already pronounced its verdict. It is curious that the life of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov is well known to literary critics and historians. And if they argue about something, then on some points.

The reader can easily find out why, when and how our writers were subjected to government repressions. When and in what editions were their books published? What was the real success (marketability) of these books. What authors received royalties. With what funds, for example, Chekhov bought the Melikhovo estate. Well, Solzhenitsyn's life is scandals, shocking, triumphs and a sea of white spots, and it is precisely at the most turning points in his biography.

But in 1974 Solzhenitsyn ended up not just anywhere, but in Switzerland, and right there in April 1976 - in the USA. Well, in the "free world" you can not hide from the public and journalists. But even there Solzhenitsyn's life is known only in fragments. For example, in the summer of 1974, for fees from the Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn created the Russian Public Fund for Assistance to the Persecuted and Their Families to help political prisoners in the USSR (parcels and money transfers to places of detention, legal and illegal material assistance to the families of prisoners ).

"Archipelago" was published with a circulation of 50,000 copies. The Soviet media at the time made jokes about the illiquid deposits of Solzhenitsyn's books in bookstores in the West. One of the secrets of Solzhenitsyn and the CIA is the ratio of sold to the number of destroyed copies of Solzhenitsyn's books.

Well, okay, let's say that all 50 thousand were sold. But what was the fee? Unknown.

It is curious that in the United States at the end of the twentieth century they came up with an analogue of the Soviet "Union of Writers" with its literary fund. That is, the writer teaches somewhere - at universities or in some training centers for novice writers. Thus, there is a “feeding” of those who write works pleasing to Western states and business.

But Solzhenitsyn, unlike Yevtushenko and many others, did not teach anywhere. However, in 1976 he purchased an expensive 50-acre(!) estate in Vermont. Together with the estate, a large wooden house with furniture and other equipment. Nearby, Solzhenitsyn is building a large three-story house “for work” and a number of other buildings.

Solzhenitsyn's sons study in expensive private schools. Alexander Isaakovich (we will now call him correctly) maintains a large staff of servants (!) And security guards. Naturally, their number and payment are unknown, if not classified. However, some eyewitnesses saw two karate champions on duty around the clock in his apartment in Switzerland.

But maybe rich Russian emigrants helped Solzhenitsyn? Not! On the contrary, he helps everyone himself, establishes foundations, maintains newspapers, such as Our Country in Buenos Aires.

"Where's the money, Zin?"

Oh! Nobel Prize! And here again the “top secret”: I received the award, but how much and where did it go?

The Nobel Prize in 1970 was awarded to A. Solzhenitsyn - "For the moral strength gleaned from the tradition of great Russian literature" which he was awarded in 1974.

For comparison, Mikhail Sholokhov, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, received 62 thousand dollars in 1965 (while it is known what he spent on the arrangement of his native village of Vyoshenskaya). This is not even enough to buy an estate and build a house. And Alexander Isaakovich did not seem to be engaged in business. So our "new Tolstoy" lived without Yasnaya Polyana and Mikhailovsky, but much richer than Lev Nikolaevich and Alexander Sergeevich. So who kept "our" "great writer"?

ANTIPATRIOTISM OF SOLZHENITSYN

In May 1974 Solzhenitsyn said:

I will go to the USA, I will speak in the Senate, I will talk with the president, I want to destroy Fulbright and all senators who intend to make agreements with the communists. I must get the Americans to increase their pressure in Vietnam.

And now Solzhenitsyn proposes to "increase the pressure." Kill a couple more million Vietnamese or unleash a thermonuclear war? Let's not forget that over 60,000 Soviet military personnel and several hundred civilian specialists fought in Vietnam.

And Alexander Isaakovich shouted: “Come on! Let's!"

By the way, he several times urged the States to destroy communism with the help of nuclear war. Solzhenitsyn publicly stated:

The course of history has placed the leadership of the world on the United States.

Solzhenitsyn congratulated General Pinochet, who carried out a coup d'état in Chile and killed thousands of people without trial or investigation in stadiums in Santiago. Alexander Isaakovich sincerely mourned the death of the fascist dictator Franco and urged the new Spanish authorities not to rush to democratize the country.

Solzhenitsyn angrily denounced American presidents Nixon and Ford for indulging and making concessions to the USSR. They de "do not interfere actively enough in the internal affairs of the USSR", and that "the Soviet people are left to the mercy of fate."

Intervene, Solzhenitsyn urged. Intervene again and again as much as you can.

In 1990 (by the new liberal authorities) Solzhenitsyn was restored to Soviet citizenship with the subsequent termination of the criminal case, and in December of the same year he was awarded the State Prize of the RSFSR for the Gulag Archipelago. According to the story of the press secretary of the President of the Russian Federation Vyacheslav Kostikov, during the first official visit of B. N. Yeltsin to the United States in 1992, immediately upon arrival in Washington, Boris Nikolayevich called Solzhenitsyn from the hotel and had a “long” conversation with him, in particular, about the Kuril Islands.

As Kostikov testified, the writer's opinion turned out to be unexpected and shocking for many:

I have studied the entire history of the islands since the 12th century. These are not our islands, Boris Nikolaevich. Need to give. But expensive...

But perhaps Solzhenitsyn's interlocutors and journalists misquoted or misunderstood our great patriot? Alas, returning to Russia, Solzhenitsyn did not renounce any of the words he had previously said. So, he wrote in the "Archipelago" and other places about 60 million prisoners in the Gulag, then about 100 million. But when he arrived, he could learn from various declassified sources that from 1918 to 1990, 3.7 million people were repressed in Soviet Russia for political reasons. The dissident Zhores Medvedev, who wrote about 40 million prisoners, publicly acknowledged the mistake and apologized, but Solzhenitsyn did not.

The writer, like any citizen, has the right to oppose the existing government. You can hate Stalin, Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Putin, but at the same time not go over to the side of Russia's enemies. Pushkin wrote insulting poems about Alexander I and was exiled. Dostoevsky participated in an anti-government conspiracy and went to hard labor. But in 1831, Alexander Sergeevich, without hesitation, wrote "Slanderers of Russia", and Fyodor Mikhailovich on the eve of the war of 1877 wrote an article "And once again that Constantinople is sooner or later, but should be ours." None of them betrayed their country.

And now in schools, portraits of Solzhenitsyn are hung between portraits of Pushkin and Dostoevsky. Shouldn't we go even further and hang portraits of Grishka Otrepyev, Hetman Mazepa and General Vlasov in the classrooms (A. Solzhenitsyn considered the latter a hero)?

End of article here:

Alexander Solzhenitsyn is an outstanding Russian writer, essayist, historian, poet and public figure.

He became widely known, in addition to literary works (as a rule, affecting acute socio-political topics), as well as historical and journalistic works about the history of Russia in the 19th-20th centuries.

Former dissident, for several decades (sixties, seventies and eighties of the XX century) actively fought against the communist regime in Russia.

The first years Solzhenitsyn lived in Kislovodsk, in 1924 he moved with his mother to Rostov-on-Don.

Already in his youth, Solzhenitsyn realized himself as a writer.

In 1937, he conceived a historical novel about the beginning of the First World War and began to collect materials for its creation. Later, this idea was embodied in "August the Fourteenth": the first part ("knot") of the historical narrative "Red Wheel".

In 1941, Solzhenitsyn graduated from the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Rostov University. Even earlier, in 1939, he entered the correspondence department of the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and Art. The war prevented him from graduating from college. After training at the artillery school in Kostroma in 1942, he was sent to the front and was appointed commander of a sound reconnaissance battery.

Solzhenitsyn went through the battle path from Orel to East Prussia, received the rank of captain, and was awarded orders. At the end of January 1945, he led the battery out of encirclement.

On February 9, 1945, Solzhenitsyn was arrested: military censorship drew attention to his correspondence with his friend Nikolai Vitkevich. The letters contained sharp assessments of Stalin and the orders he had established, spoke of the deceitfulness of modern Soviet literature. Solzhenitsyn was sentenced to eight years in the camps and eternal exile. He served his term in New Jerusalem near Moscow, then on the construction of a residential building in Moscow. Then - in a "sharashka" (a secret research institute where prisoners worked) in the village of Marfino near Moscow. He spent 1950-1953 in the camp (in Kazakhstan), was at the general camp work.

After the end of his term of imprisonment (February 1953), Solzhenitsyn was sent into indefinite exile. He began to teach mathematics in the district center of Kok-Terek, Dzhambul region of Kazakhstan. On February 3, 1956, the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union released Solzhenitsyn from exile, and a year later he and Vitkevich were declared completely innocent: criticism of Stalin and literary works was recognized as fair and not contrary to socialist ideology.

In 1956, Solzhenitsyn moved to Russia - to a small village in the Ryazan region, where he worked as a teacher. A year later he moved to Ryazan.

Even in the camp, Solzhenitsyn was diagnosed with cancer, and on February 12, 1952, he underwent an operation. During his exile, Solzhenitsyn was treated twice at the Tashkent Oncological Dispensary, using various medicinal plants. Contrary to the expectations of doctors, the malignant tumor disappeared. In his healing, the recent prisoner saw a manifestation of Divine will - a command to tell the world about Soviet prisons and camps, to reveal the truth to those who do not know anything about it or do not want to know.

Solzhenitsyn wrote the first surviving works in the camp. These are poems and a satirical play "The Feast of the Victors".

In the winter of 1950-1951, Solzhenitsyn conceived a story about a prisoner's day. In 1959, the story "Sch-854" (One Day of a Prisoner) was written. Sch-854 is the camp number of the protagonist, Ivan Denisovich Shukhov, a prisoner (convict) in a Soviet concentration camp.

In the autumn of 1961, I got acquainted with the story Chief Editor magazine "New World" A.T. Tvardovsky. Tvardovsky received permission to publish the story personally from the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union N.S. Khrushchev. "Sch-854" under a changed title - "One day of Ivan Denisovich" - was published in No. 11 of the magazine "New World" for 1962. For the sake of publishing the story, Solzhenitsyn was forced to soften some details of the life of prisoners. The original text of the story was first published by the Parisian publishing house "Ymca press" in 1973. But Solzhenitsyn retained the title "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich".

The publication of the story was a historic event. Solzhenitsyn became known throughout the country.

For the first time, the undisguised truth was told about the camp world. There were publications that claimed that the writer was exaggerating. But the enthusiastic perception of the story prevailed. For a short time, Solzhenitsyn was officially recognized.

In 1964, "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich" was nominated for the Lenin Prize. But Solzhenitsyn did not receive the Lenin Prize.

A few months after "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich," Solzhenitsyn's story "Matryona's Dvor" was published in No. 1 of Novy Mir for 1963. Initially, the story "Matryona's Dvor" was called "A village does not stand without a righteous man" - according to a Russian proverb dating back to the biblical Book of Genesis. The name "Matrenin Dvor" belongs to Tvardovsky. Like "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich", this work was autobiographical and based on real events from the life of people known to the author. The prototype of the main character is the Vladimir peasant woman Matryona Vasilievna Zakharova, with whom the writer lived, the narration, as in a number of Solzhenitsyn's later stories, is told in the first person, on behalf of the teacher Ignatich (patronymic is consonant with the author's - Isaevich), who moves to European Russia from far links.

In 1963-1966, Novy Mir published three more stories for Solzhenitsyn: "The Incident at the Krechetovka Station" (No. 1 for 1963, the author's title - "The Incident at the Kochetovka Station" - was changed at the urging of the "New World" and the conservative magazine "October", headed by the writer V.A. Kochetov), "For the benefit of the cause" (No. 7 for 1963), "Zakhar-Kalita" (No. 1 for 1966). After 1966, the writer's works were not published in his homeland until the turn of 1989, when the Nobel lecture and chapters from the book The Gulag Archipelago were published in the journal Novy Mir.

In 1964, for the sake of publishing the novel in A.T. Tvardovsky's Novy Mir, Solzhenitsyn revised the novel, softening the criticism of Soviet reality. Instead of ninety-six written chapters, the text contained only eighty-seven. The original version was about an attempt by a high-ranking Soviet diplomat to prevent Stalin's agents from stealing the secret of atomic weapons from the United States. He is convinced that atomic bomb the Soviet dictatorial regime will be invincible and can conquer the as yet free countries of the West. For publication, the plot was changed: a Soviet doctor passed on to the West information about a wonderful medicine that the Soviet authorities kept in deep secrecy.

Censorship nevertheless banned the publication. Solzhenitsyn later restored the original text with minor changes.

In 1955, Solzhenitsyn conceived, and in 1963-1966 wrote the story "Cancer Ward". It reflects the author's impressions of his stay in the Tashkent Oncological Dispensary and the history of his healing. The time of action is limited to a few weeks, the scene of action is limited to the walls of the hospital (such a narrowing of time and space - distinguishing feature poetics of many works of Solzhenitsyn).

All attempts to print the story in the "New World" were unsuccessful. "Cancer Ward", like "In the First Circle", was distributed in "samizdat". The story was first published in the West in 1968.

In the mid-1960s, when an official ban was imposed on the discussion of the topic of repression, the authorities began to consider Solzhenitsyn as a dangerous opponent. In September 1965, one of the writer's friends, who kept his manuscripts, was searched. The Solzhenitsyn archive ended up in the State Security Committee. Since 1966, the writer's works have ceased to be printed, and those already published have been removed from libraries. The KGB spread rumors that during the war Solzhenitsyn surrendered and collaborated with the Germans. In March 1967, Solzhenitsyn addressed the Fourth Congress of the Union of Soviet Writers with a letter, where he spoke about the destructive power of censorship and the fate of his works. He demanded that the Writers' Union refute the slander and resolve the issue of publishing Cancer Ward.

The leadership of the Writers' Union did not respond to this call. Solzhenitsyn's opposition to power began. He writes journalistic articles that diverge in manuscripts. From now on, journalism has become for the writer the same significant part of his work as fiction. Solzhenitsyn distributes open letters protesting against the violation of human rights and the persecution of dissidents in the Soviet Union. In November 1969, Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Writers' Union. In 1970 Solzhenitsyn won the Nobel Prize. The support of Western public opinion made it difficult for the authorities of the Soviet Union to crack down on the dissident writer.

Solzhenitsyn talks about his opposition to communist power in the book "The calf butted with the oak", first published in Paris in 1975.

Since 1958, Solzhenitsyn has been working on the book "The Gulag Archipelago" - a history of repressions, camps and prisons in the Soviet Union (Gulag - Main Directorate of Camps). The book was completed in 1968. In 1973, KGB officers seized one of the copies of the manuscript. The persecution of the writer intensified. At the end of December 1973, the first volume of the Archipelago was published in the West... (the book was published in its entirety in the West in 1973-1975).

On February 12, 1974, Solzhenitsyn was arrested and expelled from the Soviet Union to West Germany a day later. Immediately after the writer's arrest, his wife Natalya Dmitrievna distributed in "samizdat" his article "Live not by lies" - an appeal to citizens to refuse complicity in the lies that the authorities demand of them.

Solzhenitsyn and his family settled in the Swiss city of Zurich, in 1976 he moved to the small town of Cavendish in US state Vermont.

In exile, Solzhenitsyn is working on the epic "Red Wheel", dedicated to the pre-revolutionary years. The "Red Wheel" consists of four parts - "knots": "August the Fourteenth", "October the Sixteenth", "March the Seventeenth" and "April the Seventeenth". Solzhenitsyn began writing The Red Wheel in the late sixties and completed it only in the early nineties. "August the Fourteenth" and the chapters of "October the Sixteenth" were created back in the USSR.

Solzhenitsyn said that he would return to his homeland only when his books returned there, when The Gulag Archipelago was printed there. The Novy Mir magazine managed to obtain permission from the authorities to publish the chapters of this book in 1989.

In May 1994 Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia. He writes a book of memoirs "A grain fell between two millstones" ("New World", 1998, No. 9, 11, 1999, No. 2, 2001, No. 4), appears in newspapers and on television with assessments of the current policy of the Russian authorities. The writer accuses them of the fact that the transformations carried out in the country are ill-conceived, immoral and cause huge damage society, which caused an ambiguous attitude towards Solzhenitsyn's journalism.

In 1991, Solzhenitsyn wrote the book "How do we equip Russia." Powerful considerations. And in 1998, Solzhenitsyn published a book Russia in a collapse, in which he sharply criticizes economic reforms. He reflects on the need to revive the Zemstvo and the Russian national consciousness. The book "Two Hundred Years Together", devoted to the Jewish question in Russia, was published. In the "New World" the writer regularly appeared in the late nineties with literary critical articles on the work of Russian prose writers and poets.

In the nineties, Solzhenitsyn wrote several short stories and novellas: "Two stories" (Ego, On the Edge) ("New World", 1995, 3, 5), called "two-part" stories "Young", "Nastenka", "Apricot Jam" ( all - "New World", 1995, No. 10), "Zhelyabug settlements" ("New World", 1999, No. 3) and the story "Adlig Shvenkitten" ("New World", 1999, 3). The structural principle of "two-part stories" is the correlation of two halves of the text, which describe the fate of different characters, often involved in the same events, but not knowing about it. Solzhenitsyn addresses the theme of guilt, betrayal and responsibility of a person for his actions.

In 2001-2002, a two-volume monumental work "Two Hundred Years Together" was published, which the author devotes to the history of the Jewish people in Russia. The first part of the monograph covers the period from 1795 to 1916, the second - from 1916 to 1995.

In 2007, Russian President Vladimir Putin awarded Alexander Solzhenitsyn the State Prize of the Russian Federation for humanitarian work.

On the night of August 3-4, 2008 Alexander Solzhenitsyn died in Moscow. According to his relatives, the cause of death was acute heart failure.

The material was prepared on the basis of information from open sources

Date of Birth: |

|

Place of Birth: |

Kislovodsk, Terek region, RSFSR |

Date of death: |

|

A place of death: |

|

Citizenship: |

|

Occupation: |

Prose writer, publicist, poet and public figure, academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences |

Tale, short story, journalism, essay, novel, miniatures ("Tiny"), lexicography |

|

Nobel Prize in Literature (1970) |

|

Childhood and youth