Who invented these aibolit doctors. Who became the prototype of doctor aibolit from the famous tale of Chukovsky

The story of the appearance of Dr. Aibolit recalls the story of a puppet man named Pinocchio, which originates from a wooden doll named Pinocchio from an Italian fairy tale, or the story of the wizard of the Emerald City, which arose as a result of the retelling of the fairy tale by Frank Baum. Both Pinocchio and Goodwin with the company "outplayed" their predecessors in artistic implementation. The same thing happened with Dr. Aibolit.

The first image of the animal doctor was invented by the Englishman Hugh Lofting in "The Story of Doctor Doolittle" (the first book with this hero was published in 1922). Doctor Dolittle literally means "Doctor Relieve (pain)" or "Doctor Reduce (pain)". Doolittle is very fond of animals, which live in many in his house. Because of this, he loses all of his former patients and livelihood. But then his pet parrot teaches him the language of animals, and he becomes the world's best veterinarian. One day the doctor receives a message that monkeys are seriously ill in Africa, and goes on a journey to help them. On the way, he has to survive a shipwreck, he is captured by the black king, but in the end everything ends well.

Korney Chukovsky borrowed from Hugh Lofting the very figurative idea of the animal doctor and some plot moves; in addition, individual characters have moved from Dr. Doolittle's couch and from his closet to the couch and into Dr. Aibolit’s closet. But as a result, the artistic shift turned out to be so strong that it is impossible to even talk about a retelling. Chukovsky's prosaic story about Dr. Aibolit is a completely new work, albeit based on the fairy tales of Hugh Lofting. And this story is valuable not only for the exciting adventures described in it. It also contains an absolutely integral concept of the world order, which a child of five to eight years old can comprehend.

Many different animals act in the fairy tale. Here is how the house of Dr. Aibolit is “arranged”: “Hares lived in his room. There was a squirrel in the closet. There was a crow in the sideboard. A prickly hedgehog lived on the sofa. White mice lived in the chest. " The list is not limited to this, because "of all his animals, Dr. Aibolit loved most of all the duck Kiku, the dog Avva, the little pig Oink-Oink, the parrot Karudo and the owl Bumbu." But this is not all, because new ones are constantly added to the permanent inhabitants of the house (and become active acting characters).

In other words, the house of Dr. Aibolit is full of different animals, and they all coexist there in peace and harmony. I would say in an incredible peace and harmony. Nobody eats anyone, nobody fights with anyone. Even the crocodile “was quiet. I didn’t touch anyone, I lay under my bed and thought about my brothers and sisters who lived far, far away in hot Africa ”.

The inhabitants of the house are united by love and gratitude to Dr. Aibolit, about whom they say that he is very kind. Actually, this is how the tale begins: “Once upon a time there was a doctor. He was kind. " "Dobry" is the main and essential characteristic the protagonist of this story. (By the way, the main distinctive feature Dr. Doolittle - that he "knew a whole bunch of all sorts of useful things" and was "very smart.") All decisions and actions of Dr. Aibolit stem from his kindness. In Korney Chukovsky, kindness manifests itself in activity and therefore is very convincing: a good doctor lives for the sake of others, serves animals and poor people - that is, to those who have nothing. And his healing abilities border on omnipotence - there is not a single character whom he would undertake to heal and did not cure. Almost all the animals acting in the story, in one way or another, owe their lives to the doctor, a return to life. And of course, he understands animal language. But if Hugh Lofting in his story explains in detail how Dr. Doolittle mastered him, then about Aibolit the author only briefly says: "I learned a long time ago." Therefore, his ability to speak with animals in their language is perceived almost as primordial, as evidence of special abilities: he understands - that's all. And the animals living in the house obey the doctor and help him do good deeds.

What is this if not a children's analogue of paradise? And the image of the doctor's evil sister named Barbara, from whom impulses hostile to the world of the doctor constantly emanate, easily correlates with the image of the serpent. For example, Barbara demands that the doctor drive the animals out of the house ("from paradise"). But the doctor does not agree to this. And this pleases the child: the "good world" is strong and stable. Moreover, he constantly seeks to expand his boundaries, converting to the "faith" of Dr. to everyone else).

However, the children's “paradise”, as it should be in mythology, is opposed by another place - the source of suffering and fear, “hell”. And the absolutely kind "creator" in Chukovsky's fairy tale is opposed by the absolute villain, "destroyer" - Barmaley. (This image of Korney Chukovsky invented himself, without any prompting from Lofting.) Barmaley hates the doctor. Barmaley seems to have no obvious, "rational" motives to pursue Aibolit. The only explanation for his hatred is that Barmaley is evil. And the evil one cannot bear the good, he wants to destroy it.

The conflict between good and evil in Chukovsky's story is presented in the most acute and uncompromising form. No semitones, no "psychological difficulties" or moral torment. Evil is evil, and it must be punished - this is how it is perceived by both the author and the child. And if in the story "Doctor Aibolit" this punishment is indirect (Barmaley loses his ship to carry out pirate raids), then in the sequel, in the story "Penta and the sea robbers", the author deals with evil characters in the most ruthless way: pirates find themselves in the sea, and their are swallowed by sharks. And the ship with Aibolit and his animals, safe and sound, is sailing on to its homeland.

And, I must say, the (small) reader meets the end of the robbers with a "feeling of deep satisfaction." After all, they were the embodiment of absolute evil! The wise author saved us even from a hint of the possible existence of Barmaley's "inner world" and from describing any of his villainous thoughts.

Actually, the good doctor doesn't think about anything either. Everything we know about him follows from his actions or words. From this point of view, Chukovsky's story is "antipsychological." But the author did not intend to plunge us into inner world heroes. His task was to create just such a polar picture of the world, to represent in relief personified good and evil. And the definition of good and evil in the fairy tale is extremely clear: good means to heal, to give life, and evil means to torture and kill. Who among us can object to this? Is there anything that conflicts with this formula?

Good and evil in a fairy tale are fighting not for life, but for death, so the story about Dr. Aibolit turned out to be tense, exciting and in places scary. Thanks to all these qualities, as well as the clear opposition of good and evil, the story is very suitable for children aged five to eight.

By about five years of age, children begin to master rational logic (the period of explanations that "the wind blows because the trees sway" is over). And rationality initially develops as thinking in so-called “dual oppositions,” or clear opposites. And now the child not only learns from the words of an adult, “what is good and what is bad,” but also wants to motivate, substantiate, explain actions and deeds, i.e. wants to know why it is good or bad. At this age, the child is also a tough moralist, not inclined to search for psychological difficulties. He will discover the existence of complexity, duality and even reciprocity of some meanings later, at the age of 9-10.

As for the "scary" characteristic, this is exactly what a child needs after five years. By this age his emotional world already mature enough. And five or six years old differs from younger preschoolers in that they learn to manage their emotions. Including the emotion of fear. Child's request for scary, including scary tales, associated with the need for emotional "training" and an attempt to determine your threshold of tolerance. But these experiments in full force he will have to put on himself in adolescence.

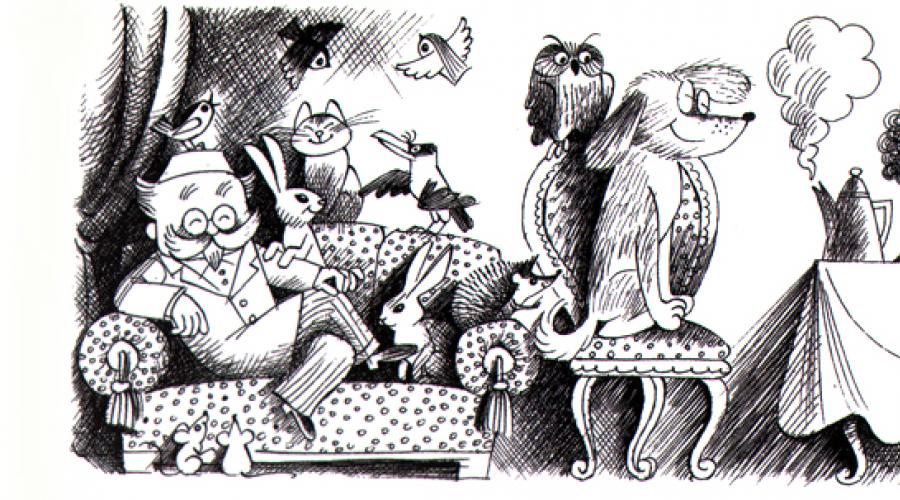

The illustrations of Viktor Chizhikov, as strange as it may sound, are in some contradiction with the tension and "horror" of the tale. The images in the illustrations are funny, funny. Doctor Aibolit is so round, rustic. Most characters have mouths stretched out in a smile. And even the most dramatic moments - the attack of pirates, the clash of pirates with sharks - are depicted cheerfully, with humor. And in the story itself there is not a drop of humor. There is nothing fun about the battle between good and evil. It's not even clear at what point in the story you can smile. So Chizhikov's drawings seem to reduce the degree of drama and thereby give the reader a break. Well, and to think that maybe everything is not so scary.

Marina Aromshtam

A veterinarian, of course, is a noble profession. In medical care for a dumb creature,

who cannot even explain that he is in pain, there is something similar to the treatment

a small child. True, sometimes patients of veterinarians can easily crush or swallow their attending physician. Noble and dangerous work veterinarians are an excellent basis for literary works... The main book healers of animals are the Russian Aibolit and the English Dolittle. In fact, these two characters are close relatives.

The animal doctor Dolittle, the personification of kindness and compassion, was born in a place not very suitable for these feelings - in the trenches of the First World War. It was there in 1916 that Lieutenant of the Irish Guards Hugh John Lofting, in order to cheer up the remaining son Colin and daughter Elizabeth Mary, who remained in England, began in letters

for them to compose a fairy tale, illustrating it with his own hand. The war went on for a long time, the tale turned out to be a long one. In 1920, already in the USA, where the Loftings moved, these letters caught the eye of a familiar publisher, who was delighted with both fairy tales and pictures. In the same year, The Story of Dr. Dolittle was published.

It was quickly followed by "Travels of Doctor Dolittle", "Post ...", "Circus ...", "Zoo ...", "Opera ..." and "Park ..." by the same doctor. In 1928, Lofting got tired of his character and, wanting to get rid of him, sent him to the moon. But readers longed for sequels, and five years later, The Return of Doctor Dolittle happened - his Diary was published. Three more stories about the veterinarian were published after the death of Hugh Lofting in 1947.

* Hugh John Lofting

-------

When the adventures of John Doolittle, MD, took place, the opening lines of the first book read vaguely: "A long time ago, when your grandparents were still young." Judging by the entourage, carriages and sailing ships, the courtyard was in the 1840s. But the place where he lived is marked quite accurately - central England, a small invented town of Paddleby. He was not an animal doctor, but an ordinary, human one, but he loved animals so much that he discouraged all clientele from his house, full of variegated fauna. The parrot Polynesia, or simply Polly, taught him the animal language, and four-legged and winged patients rushed to Dolittle from all around. The fame of the wonderful doctor quickly spread throughout the world and African monkeys, who were mowed down by the epidemic, called him to help. Dolittle, with several animal helpers, hurried to the rescue, but in Africa he was captured by the king of black savages. A daring escape, a cure for the suffering and a gorgeous gift from the rescued in the form of an unprecedented two-headed antelope. Way back, captured again, fearsome sea pirates, liberation little boy and returning home.

And this is an incomplete list of the adventures of just the first story. And then Doctor Dolittle travels with animals all over England, makes money in the circus and menagerie, organizes the world's best bird mail, gets to the island with dinosaurs, puts on an opera written by a piglet, and goes

into space ... As already mentioned, the profession of a veterinarian is dangerous, but very interesting.

John Doolittle got to Soviet readers surprisingly quickly. In 1920, a book about him was published in the USA, two years later in England, and already in 1924 in the USSR, The Adventures of Doctor Doolittle, translated by Lyubov Khavkina, with pictures by the author, was published. Lyubov Borisovna faithfully translated all the adventures of the doctor. She did not Russify the names of the characters, but simply transcribed them. For example, a two-headed herbivore was called in its version a pushmipulu. The footnote explained that this strange word “means Tolkmen - Dergtebya”. The seven thousandth print run of this edition sold out, remaining almost unnoticed by historians of children's literature. The era of Aibolit was approaching.

* Dr. Dolittle. Jersey Island stamp, 2010

-------

According to the recollections of Korney Chukovsky, he invented a doctor (though then his name sounded like Oybolit) in 1916 on a train from Helsingfors (Helsinki) to Petrograd, entertaining and comforting his sick son. But from the oral history of the road to the book fairy tale was far - as from Finland to Africa. Only in 1924, Korney Ivanovich began to translate Lofting's story, simultaneously retelling it to his little daughter Mura. The translation, or rather the retelling of Chukovsky, was first published in 1925 and was very different from the original. It was not for nothing that the writer followed the children's reaction to what was written while working - the text was clearly adapted for the youngest readers. All unnecessary details have disappeared from it, it turned out much

More concise than Khavkina's translation. Doctor Dolittle became Aibolit, his residence lost everything national traits, the help-animals received names that were familiar to Russian ears, and the writer simply and clearly called the two-headed antelope Tyanitolkay. True, this translation was very different from the fairy tale "Doctor Aibolit", which is still being published today. In Africa, Aibolit and his friends were captured by the Negro king Chernomaz, and on the way back he returned home without any adventures. Chukovsky left only twenty chapters of the loft

fourteen. He dedicated his retelling to "dear doctor Konukhes - the healer of my chukovyats."

* Roots Chukovsky with his daughter Mura

In the same 1925, Aibolit appeared in a poetic tale, though not yet in his own, but as a character of "Barmaley": a doctor who flew over Africa in an airplane tried to save Tanya and Vanya from the clutches of robbers, but he himself got into the fire, from where he politely asked the crocodile to swallow Barmaley. Then, succumbing to the moans of the bandit, he petitioned for his release. It is interesting that in both books of 1925 Aibolit is depicted by illustrators as a typical bourgeois: in a tailcoat, top hat and with a thick belly. Soon Korney Ivanovich began to compose poetic tales about the doctor. "Aibolit" was published in 1929 in three issues of the Leningrad magazine "Yozh". Chukovsky further simplified the lofting plot

and rhymed what was left of him. Doctor Aibolit almost lost his individual traits, retaining only two, but very important for children - kindness and courage. Due to the blurring of the image, illustrators painted it in their own way. But their doctor invariably resembled doctors whom little readers could meet in the nearest hospital. The readers really liked the methods of treatment that Aibolit applied to his tailed patients: chocolates, gogolmogol, pats on the tummies, and from purely medical procedures - only an endless measurement of temperature. It was impossible not to love such a doctor, and Soviet literature received a new positive hero... In the same year, Aibolit appeared in another Chukovsky's tale - "Toptygin and the Fox". He at the request

stupid bear sewn that peacock tail.

In 1935, a fairy tale in verse about Aibolit was published as a separate edition. True, it was called "Limpopo". Subsequently, Korney Ivanovich renamed

a poem in "Aibolit", and the name "Doctor Aibolit" remained behind a prosaic tale-tale.

It was published in 1936. Chukovsky himself appeared on the cover as the author, although title page honestly it said "According to Guyu Lofting." Compared to the publication of eleven years ago, the story has undergone significant changes... This time Kornei Ivanovich recounted the entire first book about Dolittle, breaking it into two parts. The second was called "Penta and the Bandits" and included the adventures of the doctor, missed by the narrator in 1925.

* This is how children first saw Aibolit (artist Dobuzhinsky, 1925)

-------

The first part of "A Journey to the Country of the Monkeys" has become noticeably Russified. For example, the doctor's sister, whom both Lofting and in the previous retelling was called Sarah, suddenly became a Barbarian. At the same time, Chukovsky, apparently to highlight the virtue of Aibolit, made her an evil tormentor of animals. Evil must be punished, and in the finale of the first part, Tyanitolkai throws the Barbarian into the sea. In the original source, Sarah, who was not harmful, but simply zealous, peacefully married.

All black savages also disappeared from Africa. Representatives of the indigenous population oppressed by the colonialists and their king Chernomaz were replaced by Barmaley and his pirates. It's funny that the American publishers of Lofting's fairy tale followed the same path in the 1960s and 1970s. They noticeably smoothed out some of the episodes associated with the blackness of individual characters.

* Cover of the first edition of the fairy tale "Doctor Aibolit" (artist E. Safonova)

In the 1938 edition, Chukovsky included retellings of two more episodes of Dr. Dolittle's adventures - "Fire and Water" and "The Adventure of a White Mouse." Approximately in this form, "Doctor Aibolit" is published to this day, although the writer made minor edits to the text of the story until the end of his life. The last tale Chukovsky wrote about Doctor Aibolit in the severe year of 1942. "Let's Defeat Barmaley" printed " Pioneer truth". Unlike all the other tales of Chukovsky, this one did not work out very well.

kind and utterly militarized. The peaceful Aibolitiya, inhabited by birds and herbivores, is attacked by a horde of predators and other animals that seemed terrible to Chukovsky, under the leadership of Barmaley. Aibolit riding a camel leads the defense:

"And put at the gate

Long-range anti-aircraft guns.

To a brazen saboteur

The troops did not land on us!

You machine gun frog

Buried behind a bush

To the enemy unit

Suddenly attack. "

The forces are not equal, but the valiant Vanya Vasilchikov flies to the aid of the animals from a distant country, and a radical turning point occurs in the war:

“But Vanyusha takes out a revolver from his belt

And with a revolver swoops on her like a hurricane:

And he planted the Karakul

There are four bullets between the eyes "

Defeated Barmaley was sentenced to capital punishment, carried out immediately:

"And so much fetid poison poured out

From the black heart of a murdered reptile,

That even hyenas are filthy

And they staggered as if drunk.

Fell into the grass, got sick

And every one of them died.

And good animals were saved from infection,

They were saved by wonderful gas masks. "

And there was general prosperity.

* Drawing by V. Basov for the fairy tale "Let's Defeat Barmaley. 1943)

-------

In 1943, "Let's Defeat Barmaley" was published by three publishing houses at once. At the end of the year, it was included in an anthology of Soviet poetry. And then a thunderstorm struck. Stalin personally crossed out the galleys of the collection "A War Tale". Soon devastating newspaper articles appeared. On March 1, 1944, Pravda published an article by P. Yudin, director of the Institute of Philosophy, with the eloquent title “The vulgar and harmful concoctions of K.

Chukovsky ":" K. Chukovsky transferred to the world of animals social phenomena having endowed the animals with the political ideas of "freedom" and "slavery", he divided them into bloodsuckers, parasites and peaceful workers. It is clear that nothing but vulgarity and nonsense, Chukovsky could not have worked out of this venture, and this nonsense turned out

politically harmful. " The tale "We Will Defeat Barmaley" can hardly be attributed to the number of Korney Ivanovich's creative successes, but she hardly deserved accusations "of deliberately vulgarizing the great tasks of raising children in the spirit of socialist patriotism." After such a high spread of fairy tales in verse, Chukovsky no longer wrote.

"Let's Defeat Barmaley" was published next time only in collected works in 2004. True, two fragments from this tale - "Joy" and "Aibolit

and a sparrow "(in the magazine version -" Visiting Aibolit ") - Chukovsky published as independent works.

New touches to the biography of Aibolit were added by cinematography. In the 1938 film "Doctor Aibolit", the roles of animals were played by real trained animals. With this approach, it was difficult to act out the scenes of pan-African healing, and screenwriter Yevgeny Schwartz built the plot around the events of the second and third parts of the story about the doctor. Almost the entire Aibolit film is engaged in non-medical,

and with law enforcement, he fights against pirates and their leader Benalis, who is actively assisted by the malicious Barbara. The climax is the scene sea battle using watermelons, apples and other ammunition.

The military theme continues in the cartoon "Barmaley" (1941). Tanechka and Vanechka go to Africa not for the sake of prank, but, armed with a rifle with a bayonet, to repulse the villain walking

topless, but in a top hat. Aibolit with the help of aviation supports the liberation of Africa from the Barmaley oppression. In Rolan Bykov's wonderful movie tale "Aybolit-66", the doctor, with difficulty, but still re-educates the robber and his gang.

In the film "How We Looked for Tishka" (1970) Aibolit made a career in the penitentiary

system - works in the zoo. Finally, in the animated series "Doctor Aibolit" (1984) director David Cherkassky intertwined a bunch of other Chukovsky's tales into the main plot. "Cockroach", "Stolen Sun", "Tsokotukha Fly" turned the doctor's story into a fascinating thriller.

The film adapters of Dolittle's adventures went even further. In the 1967 film, the veterinarian came up with a pretty girlfriend and the goal of life - to find the mysterious pink sea snail, and the Negro Prince Bumpo from Lofting's book was for some reason baptized into William Shakespeare H. In 1998, American political correctness made Doolittle himself a black man. From the tale, only the name of the protagonist and his ability to talk with animals remained. The action has been transferred to modern America, and the plot is practically invented from scratch. But comedian Eddie Murphy's Dolittle was so charming that the film grossed a good box office, forcing the producers to direct four sequels. True, starting with the third film, the doctor himself no longer appears on the screen - the problems of animals are resolved by his daughter Maya, who inherited her father's talent for languages. By 2009, the topic of conversations with animals was completely exhausted.

By that time, Lofting's books had already been repeatedly translated into Russian and published in our country. Most of the translations carefully followed the first editions of the Dolittle tales, ignoring the later distortions of the original source for the sake of tolerance. The versions of the translations mainly differed in the spelling of proper names. For example, the name of the protagonist was sometimes written with one letter "t",

and sometimes two. The most extravagant turned out to be Leonid Yakhnin, who did not translate the tale, but “retold” it. He mixed several stories under one cover at once, for some reason repeatedly diluted the text with the verses missing from the original and changed most of the names beyond recognition. So,

tyanitolkai are somewhat erotically called by Yakhnin "thithersudaychikami".

Despite all these translations, Hollywood turned out to be stronger than Russian book publishers, and if any of our young fellow citizens have any associations with the surname Doolittle, then, most likely, this is the image of a funny black doctor.

But Aibolit in our country will live forever - in children's books, in films, cartoons and the names of veterinary clinics.

It is not at all difficult to guess that the patient's anxious cry “Ay! Hurts!" turned into the most affectionate name in the world for a fabulous doctor, very kind, because he heals with chocolate and eggnog, rushes to the rescue through snow and hail, overcomes steep mountains and raging seas, selflessly fights the bloodthirsty Barmaley, frees a boy from pirate captivity Penta and his fisherman father, protects the poor and sick monkey Chichi from the terrible organ-grinder ..., while saying only one thing:

“Oh, if I don’t make it,

If I get lost on the way

What will become of them, of the sick,

With my beasts of the forest? "

Of course, everyone loves Aibolit: animals, fish, birds, boys and girls ...

Doctor Aibolit has an English "predecessor" - Dr. Doolittle invented by a writer Hugh Lofting .

HISTORY OF FAIRY TALE

Each of the books has its own fascinating story.

"Dr. Aibolit" K.I. Chukovsky written based on the plot of fairy tales English writerHugh Loftinga about Doctor Doolittle ("The Story of Doctor Doolittle", "The Adventures of Doctor Doolittle", Doctor Doolittle and His Beasts ).

THE PLOT OF THE FAIRY TALE

Good to the doctorAibolit come to be treated and "And a cow, and a she-wolf, and a bug, and a worm, and a bear"... But suddenly the children got sick Hippopotamus, and Dr. Aibolit goes to Africa, reaching which, he repeatedly risks his life: either the wave is ready to swallow him, then the mountains "Go under the clouds"... And in Africa, animals are waiting for their savior - Doctor Aibolit .

Finally he is in Africa:

Ten Nights Aibolit

Doesn't eat, drink or sleep,

Ten nights in a row

He heals the unfortunate beast

And he puts and puts thermometers for them.

And so he cured everyone.

Everyone is healthy, everyone is happy, everyone is laughing and dancing.

A Hippotamus sings:

“Glory, glory to Aibolit!

Glory to the good doctors! "

PROTOTYPE OF DOCTOR AIBOLIT

1. What animals lived with Dr. Aibolit?

(In the room - hares, in the closet - a squirrel, in the sideboard - a crow, on the sofa - a hedgehog, in the chest - white mice, Kiki's duck, Abba the dog, pig Oink - oink, Korudo parrot, Bumbo owl.)

2. How many animal languages did Aibolit know?

3. From whom and why did the Chichi monkey run away?

(From an evil organ grinder, because he dragged her around on a rope and beat her. Her neck hurt.)

Good doctor Aibolit!

He sits under a tree.

Come to him for treatment

Both the cow and the she-wolf

Both a bug and a worm,

And the bear!

Heal everyone, heal

Good doctor Aibolit!

And the fox came to Aibolit:

"Oh, I was bitten by a wasp!"

And he came to Aibolit watchdog:

"A chicken pecked me in the nose!"

And the hare came running

And she screamed: “Ay, ay!

My bunny got hit by a tram!

My bunny, my boy

Hit by a tram!

He was running down the path

And his legs were cut

And now he's sick and lame

My little bunny! "

And Aibolit said: “It doesn't matter!

Serve it here!

I'll sew him new legs

He will run on the track again. "

And they brought a bunny to him,

Such a sick, lame,

And the doctor sewed on his legs,

And the bunny jumps again.

And with him the mother hare

I went to dance too

And she laughs and shouts:

“Well, thank you. Aybolit! "

Suddenly from somewhere a jackal

He rode on a mare:

“Here is a telegram for you

From the Hippopotamus! "

“Come doctor,

To Africa soon

And save me doctor

Our kids! "

"What? Really

Are your children sick? "

"Yes Yes Yes! They have a sore throat

Scarlet fever, cholerol,

Diphtheria, appendicitis,

Malaria and bronchitis!

Come soon,

Good doctor Aibolit! "

“Okay, okay, I'll run,

I will help your children.

But where do you live?

On a mountain or in a swamp? "

“We live in Zanzibar,

In the Kalahari and Sahara,

On Mount Fernando Po,

Where Hippo-Po walks

Along wide Limpopo. "

And Aibolit got up, Aibolit ran.

Through fields, but forests, through meadows, he runs.

And only one word is repeated by Aibolit:

"Limpopo, Limpopo, Limpopo!"

And in his face the wind, and snow, and hail:

"Hey, Aibolit, turn back!"

And Aibolit fell and lies in the snow:

"I can't go any further."

And now to him from behind the tree

Shaggy wolves run out:

"Sit down, Aibolit, on horseback,

We will take you quickly! "

And Aibolit galloped forward

And only one word keeps repeating:

"Limpopo, Limpopo, Limpopo!"

But here is the sea in front of them -

Raging, making noise in the open.

And there is a high wave in the sea.

Now she will swallow Aibolit.

"Oh, if I drown,

If I go to the bottom

With my beasts of the forest? "

But then a whale comes out:

"Sit on me, Aibolit,

And like a big steamer

I'll take you ahead! "

And sat on the whale Aibolit

And only one word keeps repeating:

"Limpopo, Limpopo, Limpopo!"

And the mountains stand in front of him on the way,

And he begins to crawl over the mountains,

And the mountains are getting higher, and the mountains are getting steeper,

And the mountains go under the very clouds!

“Oh, if I don’t make it,

If I get lost on the way

What will become of them, of the sick,

With my beasts of the forest? "

And now from a high cliff

Eagles flew to Aibolit:

"Sit down, Aibolit, on horseback,

We will take you quickly! "

And sat on the eagle Aibolit

And only one word keeps repeating:

"Limpopo, Limpopo, Limpopo!"

And in Africa,

And in Africa,

On black

Limpopo,

Sits and cries

In Africa

Sad Hippopo.

He's in Africa, he's in Africa

Sits under a palm tree

And out to sea from Africa

He looks without rest:

Is he going in a boat

Dr. Aibolit?

And prowl along the road

Elephants and rhinos

And they say angrily:

"Why don't you have Aibolit?"

And next to the hippos

They grabbed their tummies:

They, the hippos,

The tummies ache.

And then the ostriches

Squeal like pigs.

Oh, sorry, sorry, sorry

Poor ostriches!

And they have measles and diphtheria,

And they have smallpox and bronchitis,

And their head hurts,

And the neck hurts.

They lie and rave:

“Well, why isn't he going,

Well, why doesn't he go,

Dr. Aibolit?"

And nestled next to

Toothed shark

Shark

Lies in the sun.

Ah, her little ones

The poor have sharks

For twelve days already

My teeth hurt!

And the shoulder is dislocated

The poor grasshopper;

He does not jump, he does not jump,

And he cries bitterly and bitterly

And the doctor calls:

“Oh, where is the good doctor?

When will he come? "

But now, look, some kind of bird

Closer and closer rushes through the air.

Aibolit is sitting on the bird.

And he waves his hat and shouts loudly:

"Long live dear Africa!"

And all the kids are happy and happy:

“I have arrived, I have arrived! Hooray! Hooray!"

And the bird is circling above them,

And the bird sits on the ground.

And Aibolit runs to the hippos,

And slaps them on the tummies

And all in order

Gives a chocolate bar

And he puts and puts thermometers for them!

And to the striped

He runs to the cubs.

And to the poor humpbacks

Sick camels

And every gogol,

Every mogul

Nogol-mogul,

Nogol-mogul,

Gogol-mogul treats.

Ten Nights Aibolit

Doesn't eat, doesn't drink and doesn't sleep,

Ten nights in a row

He heals the unfortunate animals

And he puts and puts thermometers for them.

So he cured them,

Limpopo!

So he cured the sick.

Limpopo!

And they went to laugh,

Limpopo!

And dance and indulge

Limpopo!

And the shark Karakul

Winked with her right eye

And laughs and laughs,

As if someone tickles her.

And baby hippos

Grabbed the tummies

And they laugh, they fill up -

So the oaks are shaking.

Here comes Hippo, here comes Popo,

Hippo-popo, Hippo-popo!

Here comes the Hippopotamus.

It comes from Zanzibar.

He goes to Kilimanjaro -

And he shouts, and he sings:

“Glory, glory to Aibolit!

Glory to the good doctors! "

Analysis of the poem "Aybolit" by Chukovsky

The work of Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky is based on the theme of love for animals and the glorification of one of the most difficult, but noble professions- doctor. The protagonist of the tale is Doctor Aibolit, who embodies kindness, sensitivity and compassion for others.

The central idea of the fairy tale: healing the poor and sick animals. The doctor takes on the treatment of any animals that turn to him for help. So the tram of the inconsolable hare ran over her son's legs. Aibolit heals the baby: it sews on new legs.

One day a disturbing telegram is brought to the doctor. The animals very much asked her to go to Aibolit in Africa in order to cure their children, who fell ill with serious and incomprehensible diseases. The doctor sets off: runs through the fields and forests, without even stopping to rest. The doctor is assisted by wolves: they carry him on their backs. A whale helps to swim across the sea, and eagles to fly over high mountains.

For ten days Aibolit has been treating patients in Africa: it measures the temperature of animals, gives chocolate and eggnog. When everyone finally recovers, the animals arrange a holiday. They sing and dance and glorify good doctor... The work demonstrates to us that animals cannot be treated in the same way as things or objects. They are exactly the same living creatures.

The tale is written in the simplest possible childish language. It is easy to read, but at the same time has a huge educational value... The work highlights those basic qualities, without which it is impossible to live in the world. Aibolit does not refuse to help anyone, tries to pay attention and time to any animal. By his example, the doctor shows how important it is to be near those who need help.

In the wonderful work of Chukovsky, we clearly see how strong friendship and mutual assistance can create a real miracle. The doctor heals the animals, and they respond to him with love and gratitude. The strength of a close-knit team is perfectly demonstrated here. It will be difficult to resist this alone dangerous enemy how, but with joint efforts it is great.

It doesn't matter at all whether you are a human or a beast. We all equally need love, support and faith in a miracle. If each of us is one a certain moment will be able to lend a helping hand to those who are weaker, this world will definitely become a better place. You should always have friends and not leave them in difficult times.

Leningrad, State Publishing House, 1925.35 p. with silt. Circulation 10,000 copies. In col. publishing lithographic cover. Extremely rare!

In 1924, a book was published in the Leningrad branch of Detgiz, on the title page of which it read: "Lofting Guy. Doctor Aibolit. There are four things worth paying attention to in this output: the name of the author, the title, the wording "retold for young children", and the release date. The most simple problem- with a date. The year 1925 on the title page is a common ploy in publishing practice, when a book published at the end of November or December is marked the next year to preserve the novelty of the publication. The name of the author, incorrectly indicated in both of the first Russian editions of Lofting (as retold by Chukovsky and translated by Khavkina), is a publishing mistake. The name of the author (the initial "N." on the cover of the original edition) was misinterpreted by employees of the State Publishing House, possibly (if the name was known at all) as an abbreviated form. This error indirectly testifies, by the way, to one important circumstance. Russian Lofting started out as a publishing project. Moreover, the project is "of different ages" - Khavkin translated the material provided by the publishing house for the middle age, Chukovsky retold it for the younger. Probably, the publication of a series of books was planned (in any case, in the afterword to Lyubov Khavkina's translation, Lofting's second book from the series - "The Travels of Doctor Doolittle" was announced, and it was promised that "this book will also be published in Russian translation in the Gosizdat edition"). For obvious reasons, there was no continuation. Neither the second nor the third books came out in the twenties.

One of the features creative manner Chukovsky is the presence of the so-called. “Cross-cutting” characters who move from fairy tale to fairy tale. At the same time, they do not combine works into a certain sequential "serial", but, as it were, exist in parallel in several worlds in different variations. For example, Moidodyr can be found in "Telefon" and "Bibigon", and Crocodil Krokodilovich - in "Telefon", "Moidodyr" and "Barmaley". No wonder Chukovsky ironically called his fairy tales "crocodiliades". Another favorite character - Behemoth - exists in Chukovsky's "mythology" in two guises - actually Behemoth and Hippopotamus, which the author asks not to confuse ("Behemoth is a pharmacist, and Hippopotamus is a king"). But, probably, the most versatile characters of the writer were the good doctor Aibolit and the evil cannibal pirate Barmaley. So in the prosaic "Doctor Aibolit" ("retelling according to Guy Lofting") the doctor is from the foreign city of Pindemont, in "Barmaley" - from Soviet Leningrad, and in the poem "Let's Defeat Barmaley" - from the fabulous country of Aibolitia. The same is with Barmaley. If in eponymous tale he corrects himself and goes to Leningrad, then in a prosaic version he is devoured by sharks, and in "We Will Defeat Barmaley" he is completely shot from a machine gun. Tales about Aibolit are a constant source of controversy about plagiarism. Some believe that Korney Ivanovich shamelessly stole the plot from Hugh Lofting and his fairy tales about Doctor Dolittle, while others believe that Chukovsky had Aibolit earlier and only later was used in Lofting's retelling. And before we begin to restore the "dark" past of Aibolit, it is necessary to say a few words about the author of "Doctor Dolittle".

So Hugh Lofting was born in England in 1886 inMaidenhead (Berkshire) in a mixed Anglo-Irish familyand, although from childhood he adored animals (he loved to tinker with them on his mother's farm and even organized a home zoo), he learned not at all to be a zoologist or veterinarian, but to be a railway engineer. However, the profession allowed him to visit exotic countries in Africa and South America.After graduating in 1904. private school at Chesterfield decided to devote himself to a career as a civil engineer. He went to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in America. A year later he returned to England, where he continued his studies at the London Polytechnic Institute. In 1908, after short attempts to find a decent job in England, he moved to Canada. In 1910 he worked as an engineer on a railroad in West Africa, then again on a railroad in Havana. But by 1912, the romance of changing places and the hardships of this kind of camping life began to pall, and Lofting decided to change his life: he moved to New York, got married and became a writer, got a family and even began to write various profile articles in magazines. In many articles devoted to Lofting's life, a curious fact is noted: the first story of a former engineer, who traveled around the world and gained a wide variety of impressions, was not at all about African or Cuban exoticism, but about drainage pipes and bridges. To people who know Lofting only from the epic about the adventures of Dr. Dolittle, it seems at all strange that he began as a completely "adult" writer and that "The History of Doctor Dolittle", so noticeably different in tone and naivety of presentation from other books, is not " first experience of a novice writer ". By 1913, Lofting the writer already had a fairly stable reputation among the publishers of New York magazines, in which he regularly publishes his short stories and essays. Life is gradually getting better. Children are born: Elizabeth in 1913. and Colin in 1915. By the start of World War I, Lofting is still a British subject. In 1915 he joined the British Ministry of Information, and in 1916 he was drafted into the army as a lieutenant in the Irish Guard (Lofting's mother is Irish).His children missed their dad very much, and he promised to constantly write letters to them. But will you write to the kids about the surrounding carnage? And so, impressed by the picture of horses dying in the war, Lofting began to compose a fairy tale about a kind doctor who learned the animal language and helped various animals in every possible way. The doctor received a very speaking name"Do-Little" ("Do little"), which makes you remember Chekhov and his principle of "small deeds".

So Hugh Lofting was born in England in 1886 inMaidenhead (Berkshire) in a mixed Anglo-Irish familyand, although from childhood he adored animals (he loved to tinker with them on his mother's farm and even organized a home zoo), he learned not at all to be a zoologist or veterinarian, but to be a railway engineer. However, the profession allowed him to visit exotic countries in Africa and South America.After graduating in 1904. private school at Chesterfield decided to devote himself to a career as a civil engineer. He went to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in America. A year later he returned to England, where he continued his studies at the London Polytechnic Institute. In 1908, after short attempts to find a decent job in England, he moved to Canada. In 1910 he worked as an engineer on a railroad in West Africa, then again on a railroad in Havana. But by 1912, the romance of changing places and the hardships of this kind of camping life began to pall, and Lofting decided to change his life: he moved to New York, got married and became a writer, got a family and even began to write various profile articles in magazines. In many articles devoted to Lofting's life, a curious fact is noted: the first story of a former engineer, who traveled around the world and gained a wide variety of impressions, was not at all about African or Cuban exoticism, but about drainage pipes and bridges. To people who know Lofting only from the epic about the adventures of Dr. Dolittle, it seems at all strange that he began as a completely "adult" writer and that "The History of Doctor Dolittle", so noticeably different in tone and naivety of presentation from other books, is not " first experience of a novice writer ". By 1913, Lofting the writer already had a fairly stable reputation among the publishers of New York magazines, in which he regularly publishes his short stories and essays. Life is gradually getting better. Children are born: Elizabeth in 1913. and Colin in 1915. By the start of World War I, Lofting is still a British subject. In 1915 he joined the British Ministry of Information, and in 1916 he was drafted into the army as a lieutenant in the Irish Guard (Lofting's mother is Irish).His children missed their dad very much, and he promised to constantly write letters to them. But will you write to the kids about the surrounding carnage? And so, impressed by the picture of horses dying in the war, Lofting began to compose a fairy tale about a kind doctor who learned the animal language and helped various animals in every possible way. The doctor received a very speaking name"Do-Little" ("Do little"), which makes you remember Chekhov and his principle of "small deeds".

H. Lofting:

“My children were waiting at home for letters from me - better with pictures than without. It was hardly interesting to write reports from the front to the younger generation: the news was either too terrible or too boring. Moreover, they were all censored. One thing, however, has attracted my attention more and more - this is the significant role that animals played in the World War, and over time they seem to become no less fatalistic than humans. They risked as much as the rest of us. But their fate was very different from that of humans. No matter how seriously the soldier was wounded, they fought for his life, all the means of surgery, which had developed perfectly during the war, were sent to help him. A seriously wounded horse was shot in time with a bullet fired. Not very fair, in my opinion. If we exposed animals to the same danger that we faced ourselves, then why didn't we surround them with the same attention when they were injured? But, obviously, to operate horses at our evacuation points, knowledge of the equine language would be required. So this idea was born to me ... ".

Lofting illustrated all his books himself

In total, Dr. Dolittle Lofting wrote 14 books about Dr.

V. Konashevich, Soviet edition

the prosaic retelling of "Doctor Aibolit".

Good doctor Aibolit!

He sits under a tree.

Come to him for treatment

Both the cow and the she-wolf ...

V. Suteev, Book "Aybolit" (M: Children. Literature, 1972)

In a number of articles in Russian editions, a legend, probably at some point invented by Lofting himself, is presented that the writer's children allegedly independently handed over their father's letters to one of the publishing houses, and by the time the latter returned from the front, the book had already been published. The reality is a little more prosaic. In 1918 Lofting was seriously wounded and discharged from the army on account of his disability. His family met him in England, and in 1919 they decided to return to New York. Even before returning home, Lofting decided to rework the stories about the animal doctor into a book. By a happy coincidence, on the ship on which the family was returning to America, the writer met Cecil Roberts, a famous British poet and novelist, and she, having familiarized herself with the manuscript during the voyage, recommended that he contact its publisher, Mr. Stokes. In 1920 the first book was published by Stokes. In 1922 - the first sequel. From that moment, until 1930, Stokes began to produce one Doolittle per year. The success of the series was not phenomenal, but sustainable. By 1925 - the year of the release of the Russian translation and arrangement Lofting was already a well-known author in America and Europe. Laureate of several literary prizes... Several translations of his books are being published and are being prepared for publication. To some extent, one can even say that his doctor Doolittle has become a symbol - a symbol of the new "post-war humanism." What is this symbolism? In 1923, at the American Library Association's Newbury Prize, Lofting "confessed" that the idea for The Story of Doctor Doolittle came to his mind at the sight of horses killed and wounded in battle, impressed by the courageous behavior of horses and mules under fire, that he invented a little doctor for them in order to do for them what was not done in reality - to do little (in fact, this principle is illustrated by speaking surname doctors - do-little). But "doing a little" also means going back in time and replaying, making it impossible for what is happening today.

In this sense, "Doctor Doolittle" is not just a fairy tale or adventure series for children and adolescents, but one of the first deployed alternative history projects. No wonder the action of the epic belongs to the 30s - mid 40s. XIX century. - "almost a hundred years ago", and almost no detailed review can do without mentioning the "values" of Victorian England. In total, Lofting's Doolittle cycle contains fourteen books. Ten of them are novels written and published during the life of the author:

The Story of Doctor Dolittle. 1920;

The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle. 1922;

Doctor Dolittle's Post Office. 1923;

Circus of Doctor Dolittle (Doctor Dolittle "s Circus. 1924);

Doctor Dolittle's Zoo (1925);

Caravan of Doctor Dolittle (Doctor Dolittle's Caravan. 1926);

Doctor Dolittle's Garden (1927);

Doctor Dolittle in the Moon (1928);

Doctor Dolittle's Return. 1933;

Doctor Dolittle and the Secret Lake and the Secret Lake. 1948).

Two are compilations published by Olga Fricker (sister of Lofting's third wife, Josephine) after his death. Two more - "additional", compiled by Lofting in between: the collection of stories "Gab-Gab" s Book, An Encyclopedia of Food. 1932) and "Doctor Dolittle" s Birthday Book. 1936) - illustrated diary with quotes. Without exception, all books are equipped with author's illustrations, the heirs of those pictures with which Lofting accompanied his letters home. The books are published in a different order from their "internal chronology". Beginning with the second volume, the figure of the narrator appears in the text - Tommy Stubbins, the son of a shoemaker who works as an assistant for the doctor, other rather vividly depicted constant characters appear in a psychological manner. The action begins to build like a memory ( backdating and what is happening in the first book turns out to be not just a prehistory, but, as it were, also a memory, albeit retold from hearsay). In general, the style of the story changes noticeably. These are adventure stories for middle-aged children, full of events, numerous inserted episodes, on the alternation of which the internal logic of the story is built. It is from the second book that the animals from Lofting begin to acquire " human traits"(moreover, these human traits are not idealized, they are given" without embellishment ", animals are looking for profit, are lazy, capricious, the motivation of their actions is largely dictated by selfishness, etc.). It is from the second book that we begin to learn some details from the life of the doctor himself, his family (the life story of his sister Sarah), the people around him (Tommy Stubbins, Matthew Mugg).

In 1924, Doolittle was noticed in Soviet Russia as well. The publishing house has ordered as many as two translations of the tale. The first was designed for middle-aged children, and it was performed by E. Khavkina. Subsequently, it was forgotten and was never republished in the USSR. But the second option, which bore the title “Guy Lofting. Dr. Aibolit. For small children, it was recounted by K. Chukovsky ”, had a long and rich history. Exactly the target audience became the reason that the language of the tale is very simplified. In addition, Chukovsky wrote that he "introduced dozens of realities into his revision that are not in the original." Indeed, in new editions the "retelling" was constantly revised. So Dolittle turned into Aibolit, the dog Jeep - into Abba, the piglet Jab-Jab - into Oink-oink, the boring puritanical hypocrite and the sister of Dr. Sarah - into a very evil Barbarian, and the native king of Jolinginki and the pirate Ben-Ali will completely merge into one the image of the man-eating pirate Barmaley. And although the retelling of Doctor Aibolit was constantly accompanied by the subtitle "According to Gugh Lofting," a mysterious editorial afterword appeared in the 1936 edition:

“A very strange thing happened a few years ago: two writers at two ends of the world wrote the same tale about the same person. One writer lived overseas, in America, and the other in our USSR, in Leningrad. One was named Guyu Lofting, and the other was Korney Chukovsky. They had never seen each other and had never even heard of each other. One wrote in Russian, and the other in English, one in poetry and the other in prose. But their tales turned out to be very similar, because in both tales one and the same hero: a kind doctor who heals animals ... ".

So after all: who invented Aibolit? If you do not know that the first retelling of Lofting came out back in 1924, then it seems that Chukovsky simply took Aibolit from his poetic tales and simply put it in the retelling. But taking this fact into account, everything does not look so clear, because Barmaley was written in the same year as the retelling, and the first version of the poetic Aibolit was written 4 years later. Here, probably, one of the paradoxes arises in the minds of people comparing the worlds of Dr. Doolittle and Dr. Aibolit. If we proceed not just from the first tale of Lofting, but at least from three or four stories of the cycle, we begin to consider it as part of the whole, as a kind of preliminary approach, only denoting, sketching the system of relationships between characters, but not yet conveying all its complexity and completeness (despite the fact that the kernel still remains there, in the first book). The characters change, the narrator (Tommy Stubbins) matures, potential readers mature (this is, of course, not some kind of "distinguishing feature" of the Lofting cycle, the same happens with the heroes of Milne, Tove Janson, Rowling, etc.). When we start comparing the Lofting cycle with the Chukovsky cycle, it turns out that (with practically equal volumes) the heroes of Chukovsky's fairy tales remain, as it were, unchanged. The point is not even the absence of a "continuous chronology". Each of Chukovsky's fairy tales is a separate world, and these worlds are not just parallel, they influence each other, they are mutually permeable (albeit up to a certain limit). In fact, we cannot even say anything definite about the identity of the heroes. Indeed, Aibolit "Barmaleya", Aibolit "Limpopo", Aibolit different options Lofting's "Doctor Aibolit", Aibolit "military fairy tale", etc., etc. - is it literally the same hero? If so, why does one live somewhere abroad, the other in Leningrad, the third in the African country of Aibolitia? And Barmaley? And the Crocodile? And why, if Barmaley was eaten by sharks, he again attacks Aibolit with Tanya-Vanya? And if that was before, since he had already corrected himself, why does he behave himself so badly again that in the end he is eaten by sharks? Or even not sharks at all, but the valiant Vanya Vasilchikov chops off his head? We are dealing with some kind of "invariants": invariants of the heroes, what happens to them, of our assessments. That is, the first book of Lofting (retold by Chukovsky and becoming, if not the center of this world, then the first step into it) in this system of relationships does not receive the development that it received in the system of Lofting's books. Development here goes in a completely different direction. At the same time, it is also worth noting that here the texts not only lack a direct chronology, there is not even a mandatory set of the texts themselves. A potential reader will always have a truncated version at his disposal, will have an obviously fragmentary idea not even about the whole, but about the ratio of the parts at his disposal. The number of versions and editions of fairy tales that we have at the moment (only Lofting's "Doctor Aibolit" has four main versions, differing from each other not only in volume, but also in heroes, plot structure, general direction of action), gigantic book circulations (not allowing one or another rejected or corrected edition to disappear completely without a trace), the absence of clear copyright instructions, multiplied by the arbitrariness or incompetence of publishers in the selection of materials, create a situation in which the reader himself (but unconsciously, by chance) makes for himself a certain individual card reading. Whenever possible, we will try to work with the entire main body of texts, try to trace the main movements within this special space. But even in this study, it is possible to consider only the main options containing cardinal plot and semantic differences (while Chukovsky made corrections in almost all editions of the 1920-1950s).

Chukovsky himself claimed that the doctor had appeared in the first improvisational version of The Crocodile, which he composed for a sick son. K. Chukovsky, from the diary, 10/20/1955 .:

"... and there was" Doctor Aibolit "as one of actors; only it was called then: "Oybolit". I brought this doctor there in order to soften the painful impression left on Kolya by the Finnish surgeon. "

Chukovsky also wrote that the prototype of a good doctor for him was a Jewish doctor from Vilna - Timofey Osipovich Shabad, whom he met in 1912. He was so kind that he agreed to treat poor people and sometimes little animals for free.

K. Chukovsky:

“Dr. Shabad was the most good person whom I knew in my life. It happened that a thin girl would come to him, he said to her: “Do you want me to write you a prescription? No, milk will help you. Come to me every morning and get two glasses of milk. "

Whether the idea of writing a fairy tale about the animal doctor really swarmed in Chukovsky's head, or not, one thing is clear: the stimulus for its appearance was clearly an acquaintance with Lofting. And then almost original creativity began.

Belukha, Evgeny Dmitrievich(1889, Simferopol - 1943, Leningrad) - graphic artist, artist of arts and crafts, book illustrator. He studied in St. Petersburg in the engraving workshop of V.V. Mate (1911), the Higher Art School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture under the IAH (1912-1913), took lessons from V.I. Shukhaeva (1918). Lived in Leningrad. V early work worked under the pseudonym E. Nimich. He worked in the field of easel, book, magazine, applied graphics; was engaged in etching, lithography. He performed portraits, landscapes, animalistic studies and sketches; in 1921–1922 he created several miniature portraits (of his wife, EK Spadikova). Illustrated for the magazines Ves Mir, Ogonyok (1911–1912), The Sun of Russia (1913–1914); drew for "Krasnaya Gazeta" (1918), "Petrogradskaya Pravda" (1919-1920; including created the headline of the newspaper). Created ex-libris projects. He was engaged in painting porcelain at the State Porcelain Factory (1920s). In the 1920s and 1930s he mainly illustrated books for publishing houses: Gosizdat, Priboy, Academia, Lenizdat and others. Designed books: "Tales" by R. Kipling (1923), "Tales of the South Slavs" (1923), "Doctor Aibolit" by K. I. Chukovsky (1924), "Passionate Friendship" by H. Wells (1924), "Student Stories" L. N. Rakhmanov (1931), “In People” by A. M. Gorky (1933), “A Mule Without a Bridle” by Payenne of Mezieres (1934), “The Stars Look Down” by A. Cronin (1937), “The Course of Life” E. Dhabi (1939) and others. During the Great Patriotic War was in besieged Leningrad... Completed posters: "Soldier, take revenge on the German bandits for suffering Soviet people"And others, the series" Leningrad in the days of the war "(1942-1943). Since 1918 - participant of exhibitions.

Belukha, Evgeny Dmitrievich(1889, Simferopol - 1943, Leningrad) - graphic artist, artist of arts and crafts, book illustrator. He studied in St. Petersburg in the engraving workshop of V.V. Mate (1911), the Higher Art School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture under the IAH (1912-1913), took lessons from V.I. Shukhaeva (1918). Lived in Leningrad. V early work worked under the pseudonym E. Nimich. He worked in the field of easel, book, magazine, applied graphics; was engaged in etching, lithography. He performed portraits, landscapes, animalistic studies and sketches; in 1921–1922 he created several miniature portraits (of his wife, EK Spadikova). Illustrated for the magazines Ves Mir, Ogonyok (1911–1912), The Sun of Russia (1913–1914); drew for "Krasnaya Gazeta" (1918), "Petrogradskaya Pravda" (1919-1920; including created the headline of the newspaper). Created ex-libris projects. He was engaged in painting porcelain at the State Porcelain Factory (1920s). In the 1920s and 1930s he mainly illustrated books for publishing houses: Gosizdat, Priboy, Academia, Lenizdat and others. Designed books: "Tales" by R. Kipling (1923), "Tales of the South Slavs" (1923), "Doctor Aibolit" by K. I. Chukovsky (1924), "Passionate Friendship" by H. Wells (1924), "Student Stories" L. N. Rakhmanov (1931), “In People” by A. M. Gorky (1933), “A Mule Without a Bridle” by Payenne of Mezieres (1934), “The Stars Look Down” by A. Cronin (1937), “The Course of Life” E. Dhabi (1939) and others. During the Great Patriotic War was in besieged Leningrad... Completed posters: "Soldier, take revenge on the German bandits for suffering Soviet people"And others, the series" Leningrad in the days of the war "(1942-1943). Since 1918 - participant of exhibitions.

Exhibited at exhibitions: Communities of Artists (1921, 1922), Petrograd artists of all directions, original drawings of Petrograd book signs (both - 1923), Russian book signs (1926), “Graphic art in the USSR. 1917-1928 ", an anniversary exhibition of fine arts (both - 1927)," Artistic bookplate "(1928)," Woman before and after the revolution "(1930) in Petrograd (Leningrad)," Russian book sign "in Kazan (1923), "Artists of the RSFSR for 15 years" (1933), "Heroic front and rear" (1943) in Moscow and others.

Participant of many international exhibitions, including a book exhibition in Florence (1922), an exhibition of artistic and decorative arts in Paris (1925), "The Art of the Book" in Leipzig and Nuremberg (1927), "Contemporary book art on international exhibition press ”in Cologne (1928). The artist's personal exhibition was held in Leningrad (1951). The works are in the largest museum collections, among them - the State Tretyakov Gallery, Pushkin Museum im. A.S. Pushkin, State Literary Museum, State Russian Museum and others.

Our reader knows K. Chukovsky's translation much better than L. Khavkina's translation:

Lofting, Hugh John. The Adventures of Doctor Doolittle. Drawings by the author. Translated into Russian by Lyubov Khavkina. Moscow, Gosizdat, 1924.112 p. with silt. Circulation 7000 copies. Publisher's paperback. Extremely rare!

Gosizdat used illustrations by the author himself - they are funny:

Khavkina, Lyubov Borisovna(1871, Kharkov - 1949, Moscow) - Russian theorist and organizer of librarianship, a prominent librarian and bibliographer. Honored Scientist of the RSFSR (1945), Doctor of Pedagogy (1949). She was born into a family of Kharkov doctors. After graduating from the women's gymnasium in 1888-1890. taught in Sunday school, founded by Christina Alchevskaya. In 1891 he was one of the organizers of the first Kharkov free library. In the same year he began to work at the Kharkov Public Library, where he worked, intermittently, until 1918. In 1898-1901. Khavkina studied librarianship at the University of Berlin, attended the 1900 World's Fair in Paris, where she became acquainted with the methods of the American Library Association and the ideas of its founder, Melville Dewey, that had a great influence on her. In addition, in parallel with her work in the library, Khavkina graduated from the Kharkov School of Music with a degree in Music Theory, which in 1903 allowed her to organize and head the first subscription music department in the Russian public libraries in the Kharkov Public Library; Khavkina also published music reviews and reviews in Kharkov newspapers. Khavkina's library studies originate from the book "Libraries, Their Organization and Technology" (St. Petersburg: Edition of A. Suvorin, 1904), which received wide recognition in Russia and was awarded the gold medal of the 1905 World Exhibition in Liege. During the 1900-1910s. Khavkina collaborates with the magazines "Russian School", "Education", "Bulletin of education", "For the people's teacher", writes several articles for " People's encyclopedia". In 1911, the "Guide for Small Libraries" written by Khavkina was published (Moscow: Edition of the ID Sytin Partnership), which went through six editions (up to 1930); for this book Khavkina was elected an honorary member of the Russian Bibliographic Society. During the same period, Khavkina published popular science books "India: A Popular Essay" and "How People Learned to Write and Print Books" (both - Moscow: Publishing House of ID Sytin, 1907). Since 1912, Lyubov Khavkina divides her life between Kharkov and Moscow, where in 1913 at the Shanyavsky People's University, on the basis of a project drawn up by her, the first courses of librarians in Russia were opened, the need for which Khavkina spoke of back in 1904 in her report at the Third Congress Russian figures technical and vocational education... Khavkina combines teaching at courses in a number of disciplines with work for the Kharkov Public Library (in 1914 she was elected to the board of the library) and foreign trips - in 1914, in particular, Khavkina gets acquainted with the experience of organizing librarianship in the United States (New York , Chicago, California, Honolulu) and Japan, describing this experience in The New York Public Library and various reports. The work of Khavkina, "Ketter's Author's Tables in Processing for Russian Libraries" (1916), is also based on American experience - the rules for arranging books on library shelves and in library catalogs based on the principles developed by C.E. Cutter; these tables are used in Russian libraries to this day and are called colloquially "Khavkina's tables" (tables of the author's mark). In 1916, Lyubov Khavkina took part in the preparation and conduct of the founding congress of the Russian Library Society and was elected chairman of its board, remaining in this position until 1921. In 1918, Khavkina published the book "Book and Library", in which she formulates her attitude to ideological trends of the new era:

"The library lays the foundation for universal human culture, therefore the influence of state policy diminishes its task, narrows its work, gives its activity a tendentious and one-sided character, turns it into an instrument of party struggle, to which the public library, by its very nature, should be alien."

After the October Revolution, Shanyavsky University was reorganized (and essentially closed), but the librarianship department headed by Khavkina was retained as the Research Cabinet of Library Science (since 1920), which later became the basis for the Moscow Library Institute (now - Moskovsky State University culture and arts). In 1928, Lyubov Khavkina retired. Throughout the 1930-40s. she advised various Soviet organizations (not so much as a librarian, but on the foreign languages: Khavkina was fluent in ten languages). At the same time, she did not stop working on methodological works on library science, having published the books "Compilation of Indexes to the Contents of Books and Periodicals" (1930), "Consolidated Catalogs (Historical and Theoretical Practice)" (1943), etc. After the Great Patriotic War they remembered Khavkina. She was awarded the Order of the Badge of Honor (1945), she was awarded the title of Honored Scientist of the RSFSR (1945), and in 1949, shortly before her death, she was awarded the degree of Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences (for the book "Consolidated Catalogs"). Lyubov Borisovna was buried at the Miusskoye cemetery in Moscow.