Verdi's famous works. Giuseppe Verdi's operatic work: an overview

Read also

Aida and Requiem further increased Verdi's fame. He turned sixty years old. And in spite of the fact that his creative powers have not dried up, his voice is silent for a long time.

Mazzini wrote to him in 1848: “What Garibaldi and I do in politics, what our mutual friend Manzoni does in poetry, you do in music. We all serve the people as best we can. " This is exactly how - as serving the interests of the people - Verdi understood his creative task. But over the years, observing the onset of political reaction, he came into conflict with the Italian reality around him. A feeling of deep disappointment crept into his soul. Verdi retires from social activities, reluctantly accepts the title of senator conferred on him in 1860 (in 1865 he renounces it), for a long time, without leaving, he lives on his estate Sant'Agata, where he is engaged in agriculture, meets few people. He wrote with bitterness after Rossini's death: “... it was one of the glorious names of Italy. When there will be no other (the letter said about Manzoni - M. D.) - what remains for us? Our ministers and glorious "exploits" under Lisse and Custozza? ... " (This refers to the defeat of Italy in the war with Austria.).

Verdi is also hurt by the betrayal of national ideals (a direct consequence of political reaction!), Which is observed among the figures of Russian art. The fashion for everything foreign has come. The repertoire of Italian musical theaters is dominated by foreign authors. Young composers are fond of Wagner. Verdi feels lonely.

Under these conditions, he is even deeper aware of his social vocation, which he sees in preserving and further developing the classical traditions of Italian opera at the level of new ideological tasks and aesthetic requirements. The ingenious composer-patriot is now even more demanding than before with regard to his work and to those works that won him worldwide fame in the 50s. He cannot calm down on what he has achieved. This necessitates further deepening and improving the realistic method.

This is how ten long years of meditation pass, which separate the date of the end of the Requiem from the beginning of work on Othello. But it will take three more years of hard work before the premiere of Verdi's brilliant opera will take place.

None of the works required from the composer such an exertion of creative forces, such careful consideration of each of its details, as “Othello”. And not because Verdi is already over seventy years old: the music he wrote is striking in its freshness and spontaneity, it was born in a single impulse. A deep sense of responsibility for the future of Italian music made the composer so slow. This is his creative testament: he must give an even higher and more perfect expression of the national traditions of Russian opera. There is another circumstance that compelled Verdi to think over the drama of his work in such detail - its literary primary source belongs to Shakespeare, Verdi's favorite writer.

Arrigo Boito was a talented and loyal assistant in this work. (Boito's opera "Mephistopheles", which gained European fame, was written in 1868 (second edition - 1879). The composer was then fond of Wagner. "Aida" forced him to reconsider his artistic positions. Creative friendship with Verdi began in 1881, when Boito accepted participation in the revision of the libretto "Simon Bocanegra".)- by that time, already a well-known composer, a gifted writer and poet, who sacrificed his creative activity in order to become a librettist for Verdi. Back in 1881, Boito introduced Verdi full text libretto. However, the composer's intention was only gradually ripening. In 1884, he came to grips with its implementation, forcing Boito to radically alter many things (the finale of Act I; Iago's monologue - in II, in the same place - Desdemona's release; completely Act III; the last act had four editions). The music took two years to compose. The premiere of Othello, in the preparation of which Verdi took an active part, took place in Milan in 1887. It was a triumph for Italian art.

"The genius old man Verdi in" Aida "and" Othello "opens new paths for Italian musicians," Tchaikovsky noted in 1888 (Having heard Aida in 1876 in Moscow, Tchaikovsky said that he himself could not have written an opera based on such a plot and with such heroes.)... Verdi also developed these paths in the genre of comic opera. For decades, other ideas distracted him. But it is known that at the end of the 60s he wanted to write an opera based on Moliere's Tartuffe, and even before that - Shakespeare's Wives of Windsor. These plans were not realized, only at the end of his life he managed to create a work of the comic genre.

Falstaff (1893) is Verdi's last opera. It uses the content of both "The Wives of Windsor" and comic interludes from the historical chronicle of Shakespeare "Henry IV".

The work of the eighty-year-old master strikes with youthful cheerfulness, a bizarre combination of cheerful buffoonery with sharp satire (depicting the townspeople of Windsor), light playful lyrics (a couple of Nanette and Fenton in love) with a deep psychological analysis of the main image of Falstaff, about whom Verdi said that “this is not just a character , and the type! ". In the motley sequence of episodes, where skillfully perfected ensembles play an important role (the quartet and nonet of the second scene, the final fugue sparkling with wit), the unifying role of the orchestra increases, which is extremely brilliant and varied in the use of individual timbres. However, the orchestra does not overshadow, but emphasizes the richness of the melodic characteristics of the vocal parts. In this respect, Falstaff completes those Italian national traditions of comic opera, of which Rossini's The Barber of Seville was an unsurpassed example. At the same time, in the development of methods for the musical and dramatic embodiment of the rapidly unfolding stage action, Falstaff opens new stage in the history of musical theater. These techniques were mastered by young Italian composers, most notably Puccini.

Until the last days of his life, Verdi retained clarity of mind, creative inquisitiveness, loyalty to democratic ideals. He died at the age of eighty-seven on January 27, 1901.

The publication was prepared on the basis of the textbook by M. Druskin

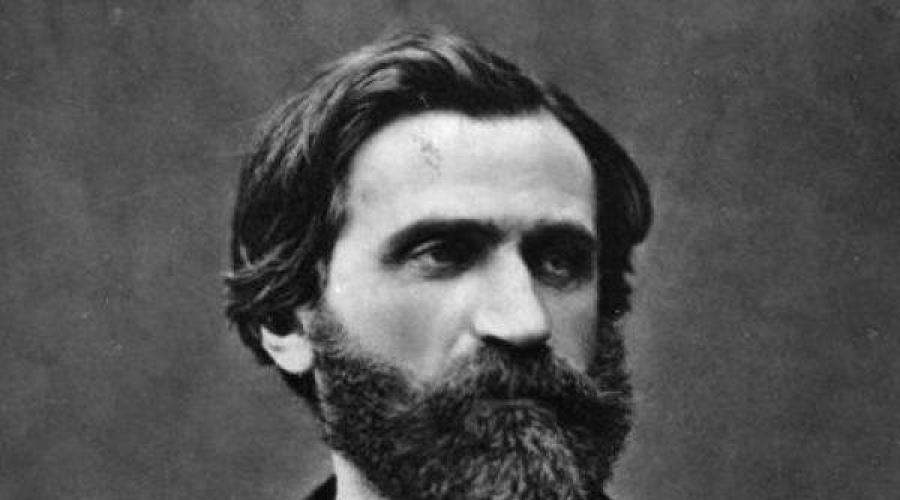

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (October 10, 1813 - January 27, 1901) is an Italian composer who became famous all over the world for his incredibly beautiful operas and requiems. He is considered the man thanks to whom the Italian opera was able to fully take shape and become what is called "the classic of all times."

Childhood

Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 10 in Le Roncole, an area near the town of Busseto, Parma province. It just so happened that the child was very lucky - he became one of the few people of that time who had the honor of being born during the emergence of the First French Republic. At the same time, Verdi's date of birth is also associated with another event - the birth on the same day of Richard Wagner, who later became the composer's sworn enemy and constantly tried to compete with him in the musical field.

Father Giuseppe was a landowner and maintained a large village tavern at that time. Mother was an ordinary spinner, who sometimes worked as a laundress and nanny. Despite the fact that Giuseppe was the only child in the family, they lived very poorly, like most of the inhabitants of Le Roncole. Of course, my father had some connections and was familiar with the managers of other, more famous inns, but they were only enough to buy the most necessary things to support the family. Only occasionally did Giuseppe, along with his parents, go to Busseto for fairs that began in early spring and lasted almost until mid-summer.

Verdi spent most of his childhood in church, where he learned to read and write. In parallel, he helped the local ministers, who in return fed him and even taught him how to play the organ. It was here that Giuseppe first saw a beautiful, huge and stately organ - an instrument that conquered him from the first second with its sound and made him fall in love forever. By the way, as soon as the son began to type the first notes on the new instrument, his parents gave him a spinet. According to the composer himself, this was a turning point in his life, and he kept an expensive gift for his whole life.

Youth

During one mass, the wealthy merchant Antonio Barezzi hears Giuseppe playing the organ. Since a man has seen many good and bad musicians in his entire life, he immediately realizes that a grandiose fate is in store for the young boy. He believes that little Verdi will eventually become a person who will be recognized by everyone, from villagers to rulers of countries. It was Barezzi who recommends Verdi to finish his studies at Le Roncole and move to Busseto, where Fernando Provezi, the director of the Philharmonic Society himself, can take care of him.

Giuseppe follows the advice of a stranger and after a while his talent is already seen by himself. However, at the same time, the director understands that without proper education, the guy will not get anything but playing the organ during the mass. He undertakes to teach Verdi literature and instills in him a love of reading, for which the young guy is incredibly grateful to his mentor. He is fond of the work of such world celebrities as Schiller, Shakespeare, Goethe, and the novel "The Betrothed" (Alexander Mazzoni) becomes his most favorite work.

At the age of 18, Verdi goes to Milan and tries to enter the Conservatory of Music, but fails the entrance exam and hears from the teachers that "he is not trained in the game so well as to apply for a place in the school." In part, the guy agrees with their position, because all this time he received only a few private lessons and still does not know much. He decides to be distracted for a while and visits several opera houses Milan. The atmosphere at the performances makes him change his mind about his own musical career... Now Verdi is sure that he wants to be exactly an opera composer.

Career and recognition

Verdi's first public appearance took place in 1830, when, after Milan, he came back to Busseto. By that time, the guy is impressed by the opera houses of Milan and at the same time completely devastated and angry that he did not enter the Conservatory. Antonio Barezzi, seeing the composer's confusion, undertakes to independently arrange his performance in his tavern, which at that time was considered the largest entertainment institution in the city. The audience welcomes Giuseppe with a thunderous ovation, which once again instills confidence in him.

After that, Verdi has lived in Busseto for 9 years and performs in Barezzi establishments. But in his heart he understands that he will only achieve recognition in Milan, since his hometown is too small and cannot provide him with a wide audience. So, in 1839 he went to Milan and almost immediately met the impresario of the Teatro alla Scala, Bartolomeo Merelli, who offered talented composer sign a contract for the creation of two operas.

Having accepted the offer, Verdi wrote the operas "The King for an Hour" and "Nabucco" for two years. The second was staged for the first time in 1842 at La Scala. The piece was waiting incredible success... During the year, it spread throughout the world and was staged over 65 times, which allowed it to firmly gain a foothold in the repertoires of many famous theaters. After Nabucco, the world heard several more of the composer's operas, including The Lombards in the Crusade and Hernani, which became incredibly popular in Italy.

Personal life

Even at the time when Verdi performs in the Barezzi establishments, he has an affair with the merchant's daughter Margarita. After asking the father's blessing, the young people get married. They have two wonderful children: daughter Virginia Maria Luisa and son Izilio Romano. However, living together after a while becomes for the spouses, rather, a burden than happiness. Verdi at that time is taken to writing his first opera, and his wife, seeing her husband's indifference, spends most of the time in her father's institution.

In 1838, a tragedy occurs in the family - Verdi's daughter dies of illness, and a year later, the son. Mother, unable to withstand such a serious shock, dies in 1840 from a long and serious illness. At the same time, it is not known for certain how Verdi reacted to the loss of his family. According to some biographers, this unsettled him for a long time and deprived him of inspiration, while others are inclined to believe that the composer was too absorbed in his work and took the news relatively calmly.

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi(ital. Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi, October 10, Roncole, near the city of Busseto, Italy - January 27, Milan) - Italian composer, central figure of the Italian opera school. His best operas ( Rigoletto, La Traviata, Aida), known for their wealth of melodic expressiveness, are often performed in opera houses around the world. Often disparaged by critics in the past (for "indulging the tastes of the common people", "simplistic polyphony" and "shameless melodramatization"), Verdi's masterpieces form the basis of the usual operatic repertoire a century and a half after they were written.

Early period

This was followed by several more operas, among them - the "Sicilian Supper" ( Les vêpres siciliennes; commissioned by the Paris Opera), Troubadour ( Il Trovatore), "Masquerade Ball" ( Un ballo in maschera), "The Force of Destiny" ( La forza del destino; written by order of the Imperial Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg), the second version of Macbeth ( Macbeth).

Operas by Giuseppe Verdi

- Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio - 1839

- King for an Hour (Un Giorno di Regno) - 1840

- Nabucco or Nebuchadnezzar (Nabucco) - 1842

- The Lombards in the First Crusade (I Lombardi ") - 1843

- Ernani- 1844. Based on the play of the same name by Victor Hugo

- Two Foscari (I due Foscari)- 1844. Based on a play by Lord Byron

- Jeanne d'Arco- 1845. Based on the play "The Maid of Orleans" by Schiller

- Alzira- 1845. Based on the play of the same name by Voltaire

- Attila- 1846. Based on the play "Attila, Leader of the Huns" by Zacharius Werner

- Macbeth- 1847. Based on the play of the same name by Shakespeare

- Rogues (I masnadieri)- 1847. Based on the play of the same name by Schiller

- Jerusalem (Jérusalem)- 1847 (Version Lombard)

- Corsair (Il corsaro)- 1848. Based on the poem of the same name by Lord Byron

- Battle of Legnano (La battaglia di Legnano)- 1849. Based on the play "The Battle of Toulouse" by Joseph Meri

- Luisa Miller- 1849. Based on the play "Treachery and Love" by Schiller

- Stiffelio- 1850. Based on the play The Holy Father, or the Gospel and the Heart, by Émile Souvestre and Eugene Bourgeois.

- Rigoletto- 1851. Based on the play The King Amuses himself by Victor Hugo

- Troubadour (Il Trovatore)- 1853. Based on the play of the same name by Antonio García Gutierrez

- La Traviata- 1853. Based on the play "Lady of the Camellias" by A. Dumas-son

- Sicilian Vespers (Les vêpres siciliennes)- 1855. Based on the play "Duke of Alba" by Eugene Scribe and Charles De Verier

- Giovanna de Guzman(Version of "Sicilian Vespers").

- Simon Boccanegra- 1857. Based on the play of the same name by Antonio García Gutierrez.

- Aroldo- 1857 (Stiffelio version)

- Masquerade ball (Un ballo in maschera) - 1859.

- The Force of Destiny (La forza del destino)- 1862. Based on the play "Don Alvaro, or the Force of Destiny" by Angel de Saavedra, Duke of Rivas, adapted for the stage by Schiller under the title "Wallenstein". Premiered at the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg

- Don Carlos- 1867. Based on the play of the same name by Schiller

- Aida- 1871. Premiered at the Khedive Opera House in Cairo, Egypt

- Otello- 1887. Based on the play of the same name by Shakespeare

- Falstaff- 1893. Based on Shakespeare's "Windsor Ridiculous"

Musical fragments

Attention! Musical excerpts in Ogg Vorbis format

- "A beauty's heart is prone to treason", from the opera "Rigoletto"(info)

Notes (edit)

Links

- Giuseppe Verdi: Sheet Music at the International Music Score Library Project

Opera Giuseppe Verdi

Oberto (1839) King for an hour (1840) Nabucco (1842) Lombards in the first crusade (1843) Hernani (1844) Two Foscari (1844)

Joan of Arc (1845) Alzira (1845) Attila (1846) Macbeth (1847) Robbers (1847) Jerusalem (1847) Corsair (1848) Battle of Legnano (1849)

Louise Miller (1849) Stifellio (1850) Rigoletto (1851) Troubadour (1853) La Traviata (1853) Sicilian Vespers (1855) Giovanna de Guzman (1855)

Verdi's work is the culmination of the development of 19th century Italian music. His creative activity, associated primarily with the genre of opera, spanned more than half a century: the first opera (Oberto, Count Bonifacio) was written by him at the age of 26, the penultimate (Othello) at 74, the last ( "Falstaff") - at 80 (!) Years. In total, taking into account six new editions of previously written works, he created 32 operas, which to this day make up the main repertory fund of theaters around the world.

A certain logic can be seen in the general evolution of Verdi's operatic creativity. In terms of themes and plots, the operas of the 1940s stand out with the priority value of plot motives, designed for a great socio-political resonance (Nabucco, Lombards, Battle of Legnano). Verdi addressed such events ancient history, which turned out to be consonant with the moods of contemporary Italy.

Already in the first operas by Verdi, created by him in the 40s, national liberation ideas, so relevant for the Italian public of the 19th century, were embodied: "Nabucco", "Lombards", "Hernani", "Jeanne d, Arc", "Atilla" , "Battle of Legnano", "The Robbers", "Macbeth" (Verdi's first Shakespearean opera), etc. - all of them are based on heroic-patriotic stories, singing praises of freedom fighters, each of them contains a direct political allusion to the social situation in Italy, which is fighting against Austrian oppression. The performances of these operas evoked an outburst of patriotic feelings among the Italian listener, poured out into political demonstrations, that is, they became events of political significance.

The melodies of opera choirs composed by Verdi acquired the meaning of revolutionary songs and were sung throughout the country. The last opera of the 40s - Louise Miller " based on Schiller's drama "Cunning and Love" - opened a new stage in Verdi's work. For the first time, the composer turned to a new topic for himself - social inequality that worried many artists second half of the XIX century, representatives critical realism ... Heroic plots are replaced by personal drama due to social reasons. Verdi shows how an unfair social order breaks human destinies... At the same time, poor, powerless people turn out to be much nobler, spiritually richer than representatives of the "high society."

In his operas of the 1950s, Verdi departs from the civic heroic line and focuses on the personal dramas of individual characters. During these years, the famous opera triad was created - "Rigoletto" (1851), "La Traviata" (1853), "Troubadour" (1859). The theme of social injustice, originating from "Louise Miller", was developed in the famous opera triad of the early 50s - Rigoletto (1851), Troubadour, La Traviata (both 1853). All three operas tell about the suffering and death of people who are socially disadvantaged, despised by "society": a court jester, a beggar gypsy woman, a fallen woman. The creation of these compositions speaks of the increased skill of Verdi as a playwright.

Compared to the early operas of the composer, this is a huge step forward:

- the psychological beginning is enhanced, associated with the disclosure of bright, extraordinary human characters;

- contrasts, reflecting life contradictions, are sharpened;

- traditional operatic forms are interpreted in an innovative way (many arias, ensembles turn into freely organized scenes);

- the role of recitation increases in vocal parts;

- the role of the orchestra is growing.

Later, in operas created in the second half of the 50s ( "Sicilian Vespers" - for the Paris Opera, "Simon Boccanegra", "Masquerade Ball") and in the 60s ( "The Force of Destiny" - commissioned by the St. Petersburg Mariinsky Theater and Don Carlos - for the Paris Opera), Verdi again returns to the historical-revolutionary and patriotic themes. However, now social and political events are inextricably linked with the personal drama of the heroes, and the pathos of the struggle, bright crowd scenes are combined with subtle psychologisms.

The best of these works is the opera Don Carlos, which exposes the terrible nature of Catholic reaction. It is based on a historical plot borrowed from the drama of the same name by Schiller. The events unfold in Spain during the reign of the despotic King Philip II, who betrays his own son into the hands of the Inquisition. Having made the oppressed Flemish people one of the main characters of the work, Verdi showed heroic resistance to violence and tyranny. This tyrannical pathos of "Don Carlos", consonant political events in Italy, in many ways prepared "Aida".

"Aida", created in 1871 by order of the Egyptian government, opens late period in the works of Verdi. This period also includes such summit creations of the composer as a musical drama. "Othello" and comic opera Falstaff (both based on Shakespeare on a libretto by Arrigo Boito).

These three operas combine the best features of the composer's style:

- deep psychological analysis of human characters;

- vivid, captivating display of conflict clashes;

- humanism aimed at exposing evil and injustice;

- spectacular entertainment, theatricality;

- democratic intelligibility musical language based on the tradition of Italian folk song.

In two recent operas based on Shakespeare's plots - "Othello" and "Falstaff" Verdi seeks to find some new ways in the opera, to give it a more in-depth study of the psychological and dramatic aspects. However, in terms of melodic weight and content (especially in Falstaff) they are inferior to previously written operas. Let us add that in quantitative terms, the operas are located along the line of "extinction". Over the last 30 years of his life, Verdi wrote only 3 operas: i.e. one performance in 10 years.

Opera by Giuseppe Verdi "La Traviata"

Plot " La Traviatas "(1853) is borrowed from the novel" The Lady of the Camellias "by Alexandre Dumas-son. As a possible operatic material, it attracted the composer's attention immediately after its publication (1848). The novel was a sensational success, and the writer soon reworked it into a play. Verdi attended its premiere and finally confirmed his decision to write an opera. He found in Dumas a theme close to him - the tragedy of a woman's fate ruined by society.

The theme of the opera caused a stormy controversy: the modern plot, costumes, hairstyles were very unusual for the audience of the 19th century. But the most unexpected thing was that for the first time the "fallen woman" appeared on the opera stage as the main character, depicted with undisguised sympathy (a circumstance specially emphasized by Verdi in the name of the opera - this is how the Italian traviata is translated). This novelty is the main reason for the scandalous failure of the premiere.

As in many other operas by Verdi, the libretto was written by Francesco Piave. Everything in it is extremely simple:

- minimum of actors;

- lack of tangled intrigue;

- the emphasis is not on the event, but on the psychological side - the spiritual world of the heroine.

The compositional plan is extremely laconic, it is concentrated on personal drama:

1st day - exposition of images of Violetta and Alfredo and the beginning of a love line (recognition of Alfredo and the emergence of a reciprocal feeling in Violetta's soul);

The second day shows the evolution of the image of Violetta, whose whole life was completely transformed under the influence of love. Already here a turn towards a tragic denouement takes place (Violetta's meeting with Georges Germont becomes fatal for her);

Day III contains the culmination and denouement - the death of Violetta. Thus, her fate is the main dramatic core of the opera.

By genre"La Traviata" - one of the first samples lyric-psychological opera. The ordinariness and intimacy of the plot led Verdi to abandon the heroic monumentality, theatrical spectacle, and showiness that distinguished his first opera works. This is the "quietest" chamber opera by the composer. The orchestra is dominated by stringed instruments, the dynamics rarely go beyond R.

Much wider than in his other works, Verdi relies on modern everyday genres... This is, first of all, the waltz genre, which can be called the "leitgenre" of "La Traviata" (vivid examples of waltz are Alfredo's drinking song, part 2 of Violetta's aria "Be Free ...", a duet of Violetta and Alfredo from 3 acts. We will leave the land ”). Against the background of the waltz, Alfred's amorous explanation in Act I takes place.

The image of Violetta.

The first characterization of Violetta is given in a short orchestral prelude, which introduces to the opera, where two opposite themes are played:

1 - the theme of "dying Violetta", anticipating the denouement of the drama. Given in the muted sound of divizi violins, in the mournful h-moll, choral texture, on second intonations. Repeating this theme in the introduction to Act III, the composer emphasized the unity of the entire composition (the method of the "thematic arch");

2 - "the theme of love" - passionate and enthusiastic, in the bright sonority of the E-dur, combines the melodiousness of the melody with the smooth waltz of the rhythm. In the opera itself, she appears as Violetta in act II at the time of her separation from Alfredo.

V I action(picture of the ball) Violetta's characteristic is based on the intertwining of two lines: brilliant, virtuoso, associated with the embodiment external essence image, and lyric-dramatic, conveying interior Violetta's world. At the very beginning of the action, the first dominates - the virtuoso. At the celebration, Violetta seems inseparable from her environment - a fun secular society. Her music is not very individualized (it is characteristic that Violetta joins Alfredo's drinking song, which is soon picked up by the entire chorus of guests).

After Alfredo's loving explanation, Violetta is at the mercy of the most contradictory feelings: here both the dream of true love and disbelief in the possibility of happiness. That's why its big portrait aria , completing the I action, is based on a contrasting comparison of two parts:

1 part - slow ("Aren't you me ..." f-moll). Differs in a pensive, elegiac character. A smooth waltz-like melody is full of thrill and tenderness, inner excitement (pauses, pp, discreet accompaniment). The theme of Alfred's love confession acts as a kind of refrain to the main melody. From now on, this beautiful melody, very close to the theme of love from the orchestral prelude, becomes the leading theme of the opera (the so-called 2nd volume of love). In Violetta's aria, she sounds several times, first in her part, and then in Alfredo, whose voice is given by the second plan.

2 part of the aria - fast ("To be free ..." As-major). This is a brilliant waltz, captivating with the swiftness of rhythm and virtuoso coloratura. A similar 2-part structure is found in many operatic arias; however, Verdi brought Violetta's aria closer to a free dream-monologue, including expressive recitative links (in them - a reflection of Violetta's spiritual struggle) and using the technique of two-plane (Alfredo's voice from afar).

Falling in love with Alfredo, Violetta left noisy Paris with him, breaking with her past. To emphasize the evolution of the protagonist, Verdi in Act II radically changes the features of her musical speech. External brilliance and virtuoso roulades disappear, intonations acquire song simplicity.

In the center II action - duet of Violetta with Georges Germont , Alfred's father. This, in the full sense of the word, is a psychological duel of two natures: the spiritual nobility of Violetta is contrasted with the philistine mediocrity of Georges Germont.

Compositionally, the duo is very far from the traditional type of singing together. This is a free stage, including recitatives, arioso, ensemble singing. In the construction of the scene, three large sections can be distinguished, connected by recitative dialogues.

Section I includes Germont's arioso "Pure, with an angel's heart" and Violetta's return solo "You will understand the power of passion." Violetta's part is distinguished by stormy excitement and contrasts sharply with the measured cantilena of Germont.

The music of the second section reflects the turning point in Violetta's mood. Germont manages to plant in her soul painful doubts about the longevity of Alfredo's love (arioso Germont "Passion passes") and she yields to his requests (" Your daughter ... "). In contrast to the 1st section, in the 2nd, joint singing prevails, in which the leading role belongs to Violetta.

Section 3 ("I will die, but in my memory") dedicated to showing Violetta's selfless determination to renounce her happiness. His music is sustained in the character of a harsh march.

The scene following the duet of Violetta's farewell letter and her parting with Alfredo is full of emotional confusion and passion, which culminates in the expressive sound of the so-called love from the orchestral prelude (in words “Ah, my Alfred! I love you so much").

The drama of Violetta, who decided to leave Alfredo, continues at Flora's ball (finale of act 2 or scene 2 of act 2). Again, as at the beginning of the opera, light-hearted dance music sounds, but now the motley bustle of the ball weighs on Violetta; she is painfully experiencing a break with her beloved. The culmination of the finale of 2 days - the wasting of Alfredo, who throws money at Violetta's feet - payment for love.

III action almost entirely dedicated to Violetta, exhausted by her illness and abandoned by everyone. Already in a small orchestral introduction, there is a feeling of an impending catastrophe. It is based on the theme of the dying Violetta from the orchestral prelude to Act I, only in a more intense c minor. It is characteristic that in the introduction to Act III there is no second, contrasting theme - the theme of love.

Central by value episode III actions - Violetta's aria "Forgive me forever"... This is a farewell to life, to moments of happiness. Before the beginning of the aria, the 2nd volume of love appears in the orchestra (when Violetta reads a letter from Georges Germont). The melody of the aria is very simple, it is based on smooth humming motives and song moves on the sixth. The rhythm is very expressive: accents on weak beats and long pauses evoke associations with difficulty breathing, with physical exhaustion. The tonal development from a-minor is directed to the parallel-mu, and then to the major of the same name, the sadder is the return to the minor. The form is couplet. The tragedy of the situation is aggravated by the festive sounds of the carnival, bursting into the open window (in the finale of Rigoletto, the Duke's song plays a similar role).

The atmosphere of approaching death is briefly illuminated by the joy of Violetta's meeting with the returning Alfredo. Their duet "We will leave the land" - this is another waltz, light and dreamy. However, Violetta's forces soon leave. The music of the last farewell sounds solemnly and mournfully, when Violetta gives Alfreda her medallion (choral chords in an ostinata rhythm on rrrr - characteristic signs of a funeral march). Just before the denouement, the theme of love sounds again in the extremely quiet sonority of stringed instruments.

Opera by Giuseppe Verdi "Rigoletto"

This is the first mature opera by Verdi (1851), in which the composer moved away from heroic themes and turned to conflicts generated by social inequality.

At the heart of plot- Victor Hugo's drama The King Is Amused, banned immediately after the premiere, as undermining the authority of the royal power. To avoid clashes with censorship, Verdi and his librettist Francesco Piave moved the scene from France to Italy and changed the names of the heroes. However, these "external" alterations did not diminish the power of social exposure: Verdi's opera, like Hugo's play, denounces the moral lawlessness and depravity of secular society.

The opera consists of those actions during which a single storyline, connected with the images of Rigoletto, Gilda and the Duke, develops intensively and rapidly. Such a focus solely on the fate of the main characters is characteristic of Verdi's drama.

Already in Act I - in the episode of Monterone's curse - that fatal outcome is foreseen, to which all the passions and actions of the heroes are drawn. Between these extreme points of the drama - the curse of Monterone and the death of Gilda - there is a chain of interconnected dramatic climaxes, relentlessly bringing the tragic ending closer.

- the scene of Gilda's abduction in the finale of Act I;

- Rigoletto's monologue and the following scene with Gilda, in which Rigoletto vows to take revenge on the Duke (II act);

- The quartet of Rigoletto, Gilda, Herzog and Maddalena is the culmination of Act III, opening a direct path to the fatal denouement.

The main character of the opera is Rigoletto- one of the brightest images created by Verdi. This is a person over whom, according to Hugo's definition, a triple misfortune gravitates (ugliness, weakness, and a despised profession). Unlike Hugo's drama, the composer named his work after him. He managed to reveal the image of Rigoletto with the deepest truthfulness and Shakespeare's versatility.

He is a man of great passions, with an extraordinary mind, but forced to play a humiliating role at court. Rigoletto despises and does not see the nobility, he does not miss the opportunity to mock the corrupt courtiers. His laughter does not spare even the fatherly grief of old Monterone. However, Rigoletto's daughter is not altogether different: he is a loving and selfless father.

The very first theme of the opera, which opens a short orchestral introduction, is associated with the image of the main character. it curse theme based on persistent repetition of one sound in a sharp-dotted rhythm, dramatic c-minor, in trumpets and trombones. The character is sinister, gloomy, tragic, emphasized by tense harmony. This theme is perceived as an image of rock, unforgiving fate.

The second theme of the introduction is called the "theme of suffering." It is based on woeful second intonations, interrupted by pauses.

V I picture of the opera(ball in the Duke's palace) Rigoletto appears in the guise of a jester. His grimaces, antics, lame gait are conveyed by the theme sounding in the orchestra (No. 189 from sheet music). It is characterized by sharp, "prickly" rhythms, unexpected accents, angular melodic turns, "clown" acting out.

A sharp dissonance in relation to the whole atmosphere of the ball is the episode associated with the curse of Monterone. His formidable and majestic music characterizes not so much Monterone as the state of mind of Rigoletto, shaken by the curse. On the way home, he cannot forget about him, so ominous echoes of the l-va of the curse appear in the orchestra, accompanying Rigoletto's recitative "Forever by those old-cem I am cursed." This recitative opens 2 a picture of the opera where Rigoletto participates in two duet scenes that are completely opposite in color.

The first, with Sparafucile, is an emphatically "businesslike", restrained conversation between two "conspirators", which did not need cantilevered singing. It is designed in gloomy colors. Both parties are thoroughly recitative and never unite. The "cementing" role is played by a continuous melody in octave unison of cellos and double basses in the orchestra. At the end of the scene, again, like an obsessive memory, l-v curses sounds.

The second scene, with Gilda, reveals a different, deeply human side of Rigoletto's character. Feelings of paternal love are conveyed through a broad, typically Italian cantilena, of which two Rigoletto's ariosos from this scene are a prime example - "Don't talk to me about her"(No. 193) and "Oh, take care of the luxurious flower"(address to the servant).

Central to the development of Rigoletto's image is his scene with courtiers after the abduction of Gilda from 2 actions... Rigoletto appears humming jester song without words, through whose feigned indifference hidden pain and anxiety are clearly felt (thanks to the minor scale, an abundance of pauses and descending second intonations). When Rigoletto realizes that his daughter is with the Duke, he throws off the mask of feigned indifference. Anger and hatred, passionate plea are heard in his tragic aria-monologue "Courtesans, fiend of vice."

The monologue has two parts. Part I is based on a dramatic declaration, in which the expressive means of the orchestral introduction to the opera are developed: the same pathetic c-minor, the speech expressiveness of the melody, the energy of the rhythm. The role of the orchestra is extremely important - the non-stop flow of strings figuration, the repeated repetition of the sigh motif, the excited pulsation of the sextuplets.

Part 2 of the monologue is built on a flowing, soulful cantilena, in which rage gives way to supplication ("Gentlemen, have mercy on me).

The next step in the development of the protagonist's image is Rigoletto the avenger. This is how he appears for the first time in a new duet scene with her daughter in act 2, which begins with Gilda's story of the abduction. Like the first duet of Rigoletto and Gilda (from the 1st act), it includes not only ensemble singing, but also recitative dialogues and arioso. The change of contrasting episodes reflects different shades of the emotional state of the characters.

The final section of the entire scene is commonly referred to as the "revenge duo." The leading role in it is played by Rigoletto, who vows to brutally take revenge on the Duke. The character of the music is very active, strong-willed, which is facilitated by a fast tempo, strong sonority, tonal stability, an ascending direction of intonation, a stubbornly repeating rhythm (No. 209). All 2 actions of the opera are concluded with a "duet of revenge".

The image of Rigoletto the avenger is developed in the central issue 3 actions, ingenious quartet where the destinies of all the main characters are intertwined. Rigoletto's gloomy determination is here opposed to the Duke's frivolity, and Gilda's mental anguish, and Maddalena's coquetry.

During a thunderstorm, Rigoletto makes a deal with Sparafucile. The picture of the storm has a psychological meaning, it complements the drama of the characters. In addition, the most important role in Act 3 is played by the Duke's lighthearted song "The Heart of Beauties", acting as an extremely vivid contrast to the dramatic events of the finale. The last performance of the song reveals to Rigoletto a terrible truth: his daughter was the victim of revenge.

Rigoletto's scene with the dying Gilda, their last duet is the denouement of the whole drama. His music is dominated by declamation.

The two other leading characters of the opera - Gilda and the Duke - are psychologically profoundly different.

The main thing in the image Gilda- her love for the Duke, for which the girl sacrifices her life. The characterization of the heroine is given in evolution.

Gilda first appears in a duet scene with her father in Act I. Her release is accompanied by a vivid portrait theme in the orchestra. Fast pace, cheerful C major, dance rhythm with "mischievous" syncopations convey both the joy of meeting and the bright, youthful appearance of the heroine. The same theme continues to develop in the duet itself, linking short, melodious vocal phrases.

The development of the image continues in the following scenes of Act I - the love duet of Gilda and the Duke and Gilda's aria.

Remembering a love date. The aria is built on one theme, the development of which forms a three-part form. In the middle section, the melody of the aria is colored with a virtuoso coloratura ornament.

Opera by Giuseppe Verdi "Aida"

The creation of Aida (Cairo, 1871) stems from a proposal by the Egyptian government to write an opera for a new opera house in Cairo to commemorate the opening of the Suez Canal. Plot was developed by the famous French scientist-Egyptologist Auguste Mariette according to an old Egyptian legend. The opera reveals the idea of the struggle between good and evil, love and hate.

Human passions and hopes collide with the inexorable fate and fate. This conflict is first presented in the orchestral introduction to the opera, where two leading leitmotifs are compared and then polyphonically combined - the theme of Aida (the personification of the image of love) and the theme of the priests (a generalized image of evil, fate).

In its style, "Aida" is in many ways close "Great French opera":

- large scales (4 acts, 7 paintings);

- decorative splendor, brilliance, "entertainment";

- an abundance of mass choral scenes and large ensembles;

- big role of ballet, solemn processions.

At the same time, elements of the "big" opera are combined with features lyric-psychological drama because the main humanistic idea is reinforced by a psychological conflict: all the main characters of the opera, who make up the love triangle, experience the most acute internal contradictions. So, Aida considers her love for Radames a betrayal before her father, brothers, homeland; in the soul of Radames, military duty and love for Aida are fighting; Amneris rushes between passion and jealousy.

The complexity of the ideological content, the emphasis on psychological conflict determined the complexity dramaturgy , which is characterized by emphasized conflict. Aida is truly an opera of dramatic collisions and intense struggle not only between enemies, but also between lovers.

1 scene I act contains exposition all the main characters in the opera, except for Amonasro, Aida's father, and string love line, which is literally referred to the very beginning of the opera. it trio of jealousy(No. 3), which reveals the complex relationships of the participants in the "love triangle" - the first ensemble scene of the opera. In his impetuous music, one can hear anxiety, the excitement of Aida and Radames, and Amneris's barely restrained anger. The orchestral part of the trio is based on the leitmotif of jealousy.

In 2 actions contrast is enhanced. In his first picture, more close-up the opposition of two rivals (in their duet) is given, and in the second picture (this is the finale of the 2nd act) the main conflict of the opera is significantly aggravated due to the inclusion in it of Amonasro, the Ethiopian captives on the one hand, and the Egyptian pharaoh, Amneris, the Egyptians on the other.

V 3 actions dramatic development is completely switched to the psychological plane - to the area of human relationships. Two duos follow one after the other: Aida-Amonasro and Aida-Radames. They are very different in expressive and compositional solutions, but at the same time they create a single line of gradually increasing dramatic tension. At the very end of the action, a plot "explosion" occurs - the involuntary betrayal of Radames and the sudden appearance of Amneris, Ramfis, and the priests.

4 action- the absolute pinnacle of the opera. Its reprisal in relation to Act I is evident: a) both open with the duet of Amneris and Radames; b) in the finale, the themes from the "initiation scene" are repeated, in particular, the prayer of the great priestess (however, if earlier this music accompanied the solemn glorification of Radames, then here is his ritual funeral service).

Act 4 has two climaxes: the tragic one in the court scene and the “quiet” lyrical one in the finale, in the farewell duet of Aida and Radames. Court scene- this is the tragic denouement of the opera, where the action develops in two parallel plans. From the dungeon, the music of the priests is heard, accusing Radames, and in the foreground, in despair, Amneris is crying to the gods. The image of Amneris is endowed with tragic features in the court scene. The fact that she, in essence, herself turns out to be a victim of the priests, brings Amneris to the positive camp: she seems to take the place of Aida in the main conflict of the opera.

The presence of a second, "quiet" climax is an extremely important feature of Aida's drama. After grandiose processions, processions, triumphal marches, ballet scenes, intense clashes, such a quiet, lyrical ending states great idea love and heroism in her name.

Ensemble scenes.

Everything the most important points in the development of psychological conflict in "Aida" they are associated with ensemble scenes, the role of which is exceptionally great. This is the "trio of jealousy", performing the function of the opening in the opera, and the duet of Aida with Amneris - the first culmination of the opera, and the duet of Aida with Radames in the finale - the denouement of the love line.

The role of duet scenes arising in the most tense situations is especially great. In act I it is a duet between Amneris and Radames, which develops into a "trio of jealousy"; in act 2 - Aida's duet with Amneris; in act 3, two duets with Aida's participation follow in a row. One of them is with his father, the other is with Radames; in act 4 there are also two duets surrounding climax scene ships: at the beginning - Radames-Amneris, at the end - Radames-Aida. There is hardly another opera in which there would be so many duets.

Moreover, they are all very individual. Aida's meetings with Radames are not of a conflicting nature and approach the type of "ensembles of consent" (especially in the finale). In the meetings of Radames with Amneris, the participants are sharply isolated, but there is no struggle, Radames evades it. But the meetings of Aida with Amneris and Amonasro in the full sense of the word can be called spiritual battles.

In terms of form, all Aida ensembles are freely organized scenes , the construction of which depends entirely on the specific psychological content. They alternate episodes based on solo and ensemble singing, recitative and purely orchestral sections. A striking example of a very dynamic scene-dialogue is the duet of Aida and Amneris from 2 acts ("duet of testing"). The images of the two rivals are shown in clash and dynamics: the evolution of the image of Amneris goes from hypocritical gentleness, insinuity to undisguised hatred.

Her vocal part is based mainly on pathetic recitative. The culmination of this development comes at the moment of "dropping the mask" - in the subject "You love, I love too"... Her fierce character, breadth of range, unexpected accents characterize Amneris' imperious, indomitable disposition.

In Aida's soul, despair is replaced by stormy joy, and then a prayer for death. The vocal style is more arios, with a predominance of mournful, pleading intonations (for example, arioso "I'm sorry and sorry" based on a sad lyric melody played against the backdrop of arpeggiated accompaniment). In this duet, Verdi uses an "invasion technique" - as if to confirm the triumph of Amneris, the sounds of the Egyptian hymn "To the Sacred Banks of the Nile" from picture I burst into his music. Another thematic arc is the theme "My Gods" from Aida's monologue from Act I.

The development of duet scenes is always conditioned by a specific dramatic situation. An example is two duets from 3 acts.Aida's duet with Amonasro begins with their full agreement, which is expressed in the coincidence of thematic (theme "We will soon return to our native land" sounds first in Amonasro, then in Aida), but its result is a psychological "distance" of images: Aida is morally depressed in an unequal duel.

Aida's duet with Radames, on the contrary, begins with a contrasting juxtaposition of images: enthusiastic exclamations of Radames ( "Again with you, dear Aida") are opposed to the mournful recitative of Aida. However, through overcoming, the struggle of feelings, the joyful, enthusiastic consent of the heroes is achieved (Radames, in an impulse of love, decides to flee with Aida).

The finale of the opera is also built in the form of a duet scene, the action of which unfolds in two parallel plans - in the dungeon (farewell to the lives of Aida and Radames) and in the temple located above it (prayer singing of the priestesses and the sobs of Amneris). The entire development of the final duet is directed towards a transparent, fragile, upward-looking theme "I'm sorry, earth, I'm sorry, the shelter of all suffering"... By its nature, it is close to the leitmotif of Aida's love.

Mass scenes.

The psychological drama in Aida unfolds against a broad backdrop of monumental crowd scenes, the music of which paints the scene (Africa) and recreates the harsh majestic images of ancient Egypt. Musical basis mass scenes are the themes of solemn hymns, victory marches, triumphal processions. In act I there are two such scenes: the scene of "the glorification of Egypt" and the "scene of the consecration of Radames".

The main theme of the glorification scene of Egypt is solemn hymn Egyptians "To the sacred banks of the Nile", which sounds after the pharaoh announced the will of the gods: the Egyptian troops will lead Radames. All those present are seized by a single belligerent impulse. Features of the anthem: chiselled marching rhythm, original harmonization (modal variability, widespread use of deviations in secondary keys), harsh coloring.

The most grandiose in scale mass scene of "Aida" - final 2 acts. As in the dedication scene, the composer uses here the most diverse elements of operatic action: singing of soloists, chorus, ballet. Along with the main orchestra, a brass band is used on stage. The abundance of participants explains multidimensionality finale: it is based on many themes of a very different nature: a solemn hymn "Glory to Egypt" melodious theme of the female choir « Laurel wreaths», a victorious march, the melody of which is led by a solo trumpet, the ominous leitmotif of the priests, dramatic theme Amonasro's monologue, Ethiopian plea for clemency, etc.

Many episodes that make up the finale of 2 days are combined into a slender symmetrical structure, consisting of three parts:

Part I has three parts. It is framed by the jubilant chorus "Glory to Egypt" and the stern chant of the priests, based on their leitmotif. In the middle, the famous march (trumpet solo) and ballet music sound.

Part 2 contrasts with its extreme drama; it is formed by episodes with the participation of Amonasro and the Ethiopian captives pleading for clemency.

Part 3 is a dynamic reprise that begins with an even more powerful sounding of the theme "Glory to Egypt". Now she unites with the voices of all the soloists on the principle of contrasting polyphony.

Like any mighty talent. Verdi reflects nationality and its era. He is the flower of his soil. He is the voice of modern Italy, not lazy-dozing or carelessly laughing Italy in comic and pseudo-serious operas by Rossini and Donizetti, not sentimentally tender and elegiac, crying Bellini's Italy, but Italy, awakened to consciousness, Italy, agitated by political storms, Italy , bold and passionate to the point of fury.

A. Serov

No one could feel life better than Verdi.

A. Boito

Verdi is a classic of Italian musical culture, one of the most significant composers XIX v. His music is characterized by a spark of high civil pathos that does not fade over time, unmistakable accuracy in the embodiment of the most complex processes taking place in the depths. human soul, nobility, beauty and inexhaustible melody. The composer owns 26 operas, spiritual and instrumental works, romances. The most significant part creative heritage Verdi is composed of operas, many of which (Rigoletto, La Traviata, Aida, Othello) have been performed from the stages of opera houses around the world for over a hundred years. Works of other genres, with the exception of the inspired Requiem, are practically unknown, the manuscripts of most of them have been lost.

Verdi, unlike many musicians of the 19th century, did not proclaim his creative principles in his programmatic speeches in print, did not associate his work with the assertion of the aesthetics of a certain artistic direction. Nevertheless, his long, difficult, not always impetuous and victorious creative path was directed towards a deeply long-suffering and conscious goal - the achievement of musical realism in an opera performance. Life in all the variety of conflicts - this is the overarching theme of the composer's work. The range of its embodiment was unusually wide - from social conflicts to the confrontation of feelings in the soul of one person. At the same time, Verdi's art carries a sense of special beauty and harmony. “I like everything in art that is beautiful,” said the composer. His own music has also become an example of beautiful, sincere and inspired art.

Clearly aware of his creative tasks, Verdi was tireless in his search for the most perfect forms of embodiment of his ideas, extremely demanding of himself, of librettists and performers. He often picked himself literary basis for the libretto, discussed in detail with the librettists the entire process of its creation. The most fruitful collaboration connected the composer with such librettists as T. Solera, F. Piave, A. Gislanzoni, A. Boito. Verdi demanded dramatic truth from the singers, he was intolerant of any manifestation of falsehood on stage, senseless virtuosity, not colored by deep feelings, not justified dramatic action... "... Great talent, soul and stage instinct" - these are the qualities that he primarily appreciated in performers. The "meaningful, reverent" performance of operas seemed necessary to him; "... when operas cannot be performed in all their integrity - as the composer intended, it is better not to perform them at all."

Verdi lived a long life. He was born into the family of a peasant innkeeper. His teachers were the village church organist P. Baistrocchi, then F. Provezi, who headed the musical life in Busseto, and the conductor of the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, V. Lavigna. Already a mature composer, Verdi wrote: “I learned some of the best works of our time, not studying them, but hearing them in the theater ... I would be lying if I said that in my youth I did not go through a long and rigorous study ... I have a hand strong enough to handle the note the way I want it to and confident enough to most of the time achieve the effects I intend; and if I write something not according to the rules, it is because the exact rule does not give me what I want, and because I do not consider all the rules adopted to this day to be unconditionally good. "

The first success of the young composer was associated with staging in Milan theater La Scala of the opera "Oberto" in 1839. Three years later, the opera "Nebuchadnezzar" ("Nabucco") was staged in the same theater, which brought the author wide fame (1841). The first operas of the composer appeared in the era of the revolutionary upsurge in Italy, which was called the Risorgimento era (Italian - revival). The struggle for the unification and independence of Italy engulfed the entire people. Verdi could not stand aside. He deeply experienced the victories and defeats of the revolutionary movement, although he did not consider himself a politician. Heroic-patriotic operas of the 40s - "Nabucco" (1841), "Lombards in the first crusade" (1842), "Battle of Legnano" (1848) - were a kind of response to revolutionary events. The biblical and historical plots of these operas, far from modern times, glorified heroism, freedom and independence, and therefore were close to thousands of Italians. "Maestro of the Italian Revolution" - this is how his contemporaries called Verdi, whose work became extremely popular.

However, the creative interests of the young composer were not limited to the theme of the heroic struggle. In search of new subjects, the composer turns to the classics of world literature: V. Hugo (Hernani, 1844), W. Shakespeare (Macbeth, 1847), F. Schiller (Louise Miller, 1849). The expansion of the theme of creativity was accompanied by the search for new musical means, the growth of composer's skill. The period of creative maturity was marked by a remarkable triad of operas: Rigoletto (1851), Troubadour (1853), La Traviata (1853). For the first time in Verdi's work, a protest against social injustice was voiced so openly. The heroes of these operas, endowed with ardent, noble feelings, come into conflict with generally accepted moral norms. Turning to such plots was an extremely bold step (Verdi wrote about La Traviata: "The plot is modern. Someone else would not take on this plot, perhaps because of decency, because of the era and because of a thousand other stupid prejudices .. I do it with the greatest pleasure ").

By the mid-50s. the name of Verdi is widely known all over the world. The composer enters into contracts not only with Italian theaters. In 1854. he creates the opera "Sicilian Vespers" for the Parisian theater Grand Opera, a few years later the operas "Simon Boccanegra" (1857) and "Masquerade Ball" (1859, for the Italian theaters San Carlo and Appolo) were written. In 1861, commissioned by the management of the St. Petersburg Mariinsky Theater, Verdi created the opera The Force of Destiny. In connection with its production, the composer twice leaves for Russia. Opera did not have great success, although Verdi's music was popular in Russia.

Among the operas of the 60s. The most popular was the opera Don Carlos (1867) based on the drama of the same name by Schiller. The music of Don Carlos, saturated with deep psychologism, anticipates the heights of Verdi's operatic creativity - Aida and Othello. Aida was written in 1870 for the opening of a new theater in Cairo. It organically merged the achievements of all previous operas: the perfection of the music, the bright colors, the sharpness of the drama.

Following Aida, Requiem (1874) was created, after which there was a long (more than 10 years) silence caused by the crisis of social and musical life. In Italy, a widespread passion for the music of R. Wagner reigned, while the national culture was in oblivion. The current situation was not just a struggle of tastes, various aesthetic positions, without which artistic practice is inconceivable, but the development of all art. It was a time when the priority of national artistic traditions fell, which was especially deeply felt by the patriots of Italian art. Verdi reasoned like this: “Art belongs to all peoples. No one believes this more firmly than I do. But it develops individually. And if the Germans have a different artistic practice than ours, their art is fundamentally different from ours. We cannot compose like the Germans ... "

Thinking about the future of Italian music, feeling a huge responsibility for each next step, Verdi set about realizing the idea of the opera "Othello" (1886), which became a true masterpiece. "Othello" is an unsurpassed interpretation of a Shakespearean plot in the operatic genre, a perfect example of a musical and psychological drama, the creation of which the composer went all his life.

Verdi's last work, the comic opera Falstaff (1892), surprises with its cheerfulness and impeccable skill; it seems to open new page the work of the composer, unfortunately, did not receive a continuation. Verdi's whole life is illuminated by a deep conviction in the correctness of the chosen path: “As far as art is concerned, I have my own thoughts, my own convictions, very clear, very precise, from which I cannot and should not give up.” L. Escudier, one of the composer's contemporaries, very aptly characterized him: “Verdi had only three passions. But they achieved the greatest strength: love for art, national feeling and friendship. " Interest in the passionate and truthful work of Verdi continues unabated. For new generations of music lovers, it invariably remains a classic standard, combining clarity of thought, inspiration of feeling and musical perfection.

A. Zolotykh

Opera was at the center of Verdi's artistic interests. At the earliest stage of his work, in Busseto, he wrote many instrumental works (their manuscripts have been lost), but never returned to this genre. An exception is the string quartet of 1873, which was not intended by the composer for public performance. In the same teenage years by the nature of his activity as an organist, Verdi composed sacred music. Towards the end of his career, after the Requiem, he created several more works of this kind (Stabat mater, Te Deum and others). A few romances also belong to the early creative period. For more than half a century, he devoted all his energies to opera, from Oberto (1839) to Falstaff (1893).

Verdi wrote twenty-six operas, six of them he gave in a new, significantly modified version. (By decades, these works are placed as follows: late 30s - 40s - 14 operas (+1 in a new edition), 50s - 7 operas (+1 in a new edition), 60s - 2 operas (+2 in a new version), 70s - 1 opera, 80s - 1 opera (+2 in a new version), 90s - 1 opera.) Throughout his long journey in life, he remained faithful to his aesthetic ideals. “I may not have enough strength to achieve what I want, but I know what I am striving for,” wrote Verdi in 1868. These words can describe all of his creative activity... But over the years it became clearer artistic ideals composer and more perfect, honed - his skill.

Verdi aspired to the embodiment of the drama "strong, simple, significant." In 1853, composing La Traviata, he wrote: “I dream of new large, beautiful, diverse, bold subjects, and extremely bold ones”. In another letter (of the same year) we read: "Give me a beautiful, original story, interesting, with magnificent situations, passions, - first of all passions! .."

Truthful and vivid dramatic situations, sharply outlined characters - this is what, in Verdi's opinion, is the main thing in the opera plot. And if in the works of the early, romantic period, the development of situations did not always contribute to the consistent disclosure of characters, then by the 50s the composer clearly realized that the deepening of this connection serves as the basis for creating a life-like musical drama. That is why, firmly taking the path of realism, Verdi condemned modern Italian opera for monotonous, monotonous plots, routine forms. He also condemned his previously written works for the insufficient breadth of showing the contradictions in life: “There are scenes in them that arouse great interest, but there is no variety. They affect only one side - the sublime, if you will - but always the same. "

In Verdi's understanding, opera is inconceivable without the extreme sharpening of conflicting contradictions. Dramatic situations, the composer said, should reveal human passions in their characteristic, individual form. Therefore, Verdi decisively opposed all sorts of routine in the libretto. In 1851, starting work on the Troubadour, Verdi wrote: “The freer the Cammarano (librettist of the opera. M. D.) will interpret the form, the better for me, the more I will be satisfied. " A year earlier, having conceived an opera based on the plot of Shakespeare's King Lear, Verdi pointed out: “It is not necessary to make a drama out of Lear in a generally accepted form. It would be necessary to find a new, larger form, free from bias. "

For Verdi, a plot is a means of effectively revealing the idea of a work. The composer's life is permeated with the search for such subjects. Starting with Ernani, he persistently seeks literary sources for their operatic designs. An excellent connoisseur of Italian (and Latin) literature, Verdi was well versed in German, French, and English drama. His favorite authors are Dante, Shakespeare, Byron, Schiller, Hugo. (About Shakespeare Verdi wrote in 1865: “He is my favorite writer, whom I know from early childhood and I constantly reread.” He wrote three operas on Shakespeare's plots, dreamed of Hamlet and The Tempest, and returned to work on “ King Lear "(in 1847, 1849, 1856 and 1869); on the plots of Byron - two operas (the unfinished concept of" Cain "), Schiller - four, Hugo - two (the idea of" Ruy Blaz ").)

Verdi's creative initiative was not limited to the choice of the plot. He actively supervised the work of the librettist. “I have never written operas on ready-made librettos, made by someone else,” the composer said, “I just cannot understand how a screenwriter can be born who can guess exactly what I can translate into an opera.” Verdi's extensive correspondence is filled with creative instructions and advice to his literary staff. These instructions relate primarily to the script plan of the opera. The composer demanded maximum concentration plot development literary source and for this - the reduction of the side lines of intrigue, the compression of the text of the drama.

Verdi prescribed to his employees the phrases he needed, the rhythm of the poems and the number of words needed for music. He paid special attention to "key" phrases in the libretto text, designed to clearly reveal the content of a specific dramatic situation or character. “It does not matter whether this or that word is needed - a phrase that will excite, will be scenic is needed,” he wrote to the librettist of Aida in 1870. Improving the libretto "Othello", he removed unnecessary, in his opinion, phrases and words, demanded rhythmic variety in the text, broke the "smoothness" of the verse, which fetters musical development, and sought the utmost expressiveness and laconicism.

Verdi's bold designs did not always receive a worthy expression from his literary collaborators. So, highly appreciating the libretto "Rigoletto", the composer noted weak verses in it. Much did not satisfy him in the drama of "Troubadour", "Sicilian Vespers", "Don Carlos". Having failed to achieve a completely convincing script and literary embodiment of his innovative idea in the libretto of King Lear, he was forced to abandon the completion of the opera.

In intense work with the librettists, Verdi finally matured the idea of the composition. He usually began music only after the development of the complete literary text of the entire opera.

Verdi said that the most difficult thing for him was "to write quickly enough to express a musical thought in the inviolability with which it was born in the mind." He recalled: "In my youth, I often worked without interruption from four in the morning to seven in the evening." Even in his old age, creating the score of Falstaff, he immediately instrumentalized completed large excerpts, as “he was afraid to forget some orchestral combinations and timbre combinations”.

When creating music, Verdi had in mind the possibilities of its stage implementation. Associated with various theaters until the mid-50s, he often solved certain issues musical drama depending on the performing forces that the group had at its disposal. Moreover, Verdi was interested not only in the vocal qualities of the singers. In 1857, before the premiere of Simon Boccanegra, he pointed out: "The role of Paolo is very important, it is absolutely necessary to find a baritone who would be a good actor." Back in 1848, in connection with the production of Macbeth planned in Naples, Verdi rejected the singer Tadolini proposed to him, since her vocal and stage skills did not fit the intended role: “Tadolini has a magnificent, clear, transparent, powerful voice, and I I would like a voice for a lady to be deaf, harsh, gloomy. Tadolini has something angelic in her voice, and I would like the lady's voice to have something devilish. "

In learning his operas, right up to Falstaff, Verdi took an energetic part, interfering with the conductor's work, paying particular attention to the singers, carefully going through the parts with them. So, the singer Barbieri-Nini, who played the role of Lady Macbeth at the premiere of 1847, testified that the composer rehearsed a duet with her up to 150 times, seeking the funds he needed vocal expressiveness... He worked just as demandingly at the age of 74 with the renowned tenor Francesco Tamagno, the performer of the role of Othello.

Verdi paid special attention to the issues of the stage interpretation of the opera. His correspondence contains many valuable statements on these issues. "All the forces of the stage provide dramatic expressiveness," wrote Verdi, "and not only the musical transmission of cavatins, duets, finals, etc." In connection with the production of The Force of Destiny in 1869, he complained about the critic, who wrote only about the vocal side of the performer: life pictures filling half of the opera and giving it the character of a musical drama, neither the reviewer nor the audience say anything ... ". Noting the musicality of the performers, the composer emphasized: “Opera, - don't get me wrong, - that is stage musical drama, was given very mediocre. " It is against this separation of music from the stage and Verdi protested: participating in the learning and staging of his works, he demanded the truth of feelings and actions both in singing and in stage movement. Verdi argued that only under the condition of the dramatic unity of all means of musical and stage expression, an opera performance can be full-fledged.

Thus, starting from the choice of the plot in the intense work with the librettist, when creating music, during its stage implementation - at all stages of work on the opera, from the conception of the idea to production, the master's imperious will manifested itself, which confidently led his native Italian art to the heights realism.

Verdi's operatic ideals were formed as a result of many years of creative work, a lot of practical work, and persistent research. He knew well the state of the contemporary musical theater in Europe. Spending a lot of time abroad, Verdi got acquainted with the best troupes in Europe - from St. Petersburg to Paris, Vienna, London, Madrid. He was familiar with the operas of the greatest composers of our time. (Probably, in St. Petersburg Verdi heard Glinka's operas. In the personal library of the Italian composer there was a clavier “ Stone guest"Dargomyzhsky.)... Verdi evaluated them with the same degree of criticality with which he approached his own work. And quite often he did not so much assimilate the artistic achievements of other national cultures as he reworked in his own way, overcame their influence.

This is how he treated the musical and stage traditions. French theater: They were well known to him, if only because three of his works (Sicilian Vespers, Don Carlos, the second edition of Macbeth) were written for the Parisian stage. Such was his attitude to Wagner, whose operas, mainly of the middle period, he knew, and some of them highly appreciated ("Lohengrin", "Valkyrie"), but Verdi creatively polemicized with both Meyerbeer and Wagner. He did not diminish their importance for the development of French or German musical culture, but rejected the possibility of slavish imitation of them. Verdi wrote: “If Germans, proceeding from Bach, reach Wagner, then they act like genuine Germans. But we, the descendants of Palestrina, imitating Wagner, commit a musical crime, create unnecessary and even harmful art. " “We feel differently,” he added.

The question of Wagnerian influence has become especially acute in Italy since the 1960s; many young composers succumbed to him (Wagner's most ardent admirers in Italy were Liszt's pupil, the composer J. Sgambatti, conductor J. Martucci, A. Boito(at the beginning of his creative career, before meeting with Verdi) and others.)... Verdi noted with bitterness: “All of us - composers, critics, the public - have done everything possible to renounce our musical nationality. Here we are at a quiet pier ... one more step, and we will be numbered in this, as in everything else. " It was hard and painful for him to hear from the lips of young people and some critics that his previous operas were outdated, did not meet modern requirements, and that the current ones, starting with Aida, are following in Wagner's footsteps. "What an honor, after forty years of creative career, to end up as a copycat!" - Verdi exclaimed angrily.

But he did not reject the value of Wagner's artistic achievements. The German composer made him think about many things, and above all - about the role of the orchestra in opera, which was underestimated by Italian composers of the first half of the 19th century (including by Verdi himself at an early stage of his work), about increasing the importance of harmony (and by this important means musical expressiveness neglected by the authors of the Italian opera) and, finally, on the development of principles of end-to-end development to overcome the dismemberment of the forms of the number structure.

However, for all these questions, which are most important for the musical drama of opera in the second half of the century, Verdi found their solutions other than Wagner's. In addition, he outlined them even before he got acquainted with the works of the brilliant German composer. For example, the use of "timbre dramaturgy" in the scene of the appearance of spirits in Macbeth or in the depiction of an ominous thunderstorm in Rigoletto, the use of string divisi in high register in the introduction to the last act of La Traviata or trombones in Miserere's Troubadour - these are bold, individual instrumentation techniques are found regardless of Wagner. And if we talk about someone's influence on Verdi's orchestra, then one should rather have in mind Berlioz, whom he greatly appreciated and with whom he was in friendly relations since the early 60s.

Verdi was just as independent in his search for a fusion of the principles of song-arios (bel canto) and declamatory (parlante). He developed his own special "mixed manner" (stilo misto), which served as the basis for him to create free forms of monologue or dialogic scenes. Rigoletto's aria "Courtesans, Fiend of Vice" or the spiritual duel between Germont and Violetta were also written before the acquaintance with Wagner's operas. Of course, acquaintance with them helped Verdi more boldly develop new principles of drama, which in particular affected his harmonic language, which became more complex and flexible. But between creative principles There are fundamental differences between Wagner and Verdi. They are clearly visible in their attitude to the role of the vocal principle in the opera.

With all the attention that Verdi paid to the orchestra in his latest compositions, he recognized the vocal-melodic factor as the leader. Thus, regarding the early operas of Puccini, Verdi wrote in 1892: “It seems to me that the symphonic principle prevails here. This is not bad in itself, but you have to be careful: an opera is an opera, and a symphony is a symphony. "

"Voice and melody," said Verdi, "will always be the most important for me." He ardently defended this position, believing that typical national features of Italian music were expressed in it. In his project for the reform of public education, presented to the government in 1861, Verdi advocated the organization of free evening singing schools, for the all-round stimulation of vocal music-making at home. Ten years later, he appealed to young composers to study classical Italian vocal literature, including works by Palestrina. In the assimilation of the peculiarities of the singing culture of the people of Verdi, he saw the guarantee of the successful development of the national traditions of musical art. However, the content that he put into the concepts of "melody" and "melody" was changing.

During the years of his creative maturity, he sharply opposed those who interpreted these concepts one-sidedly. In 1871 Verdi wrote: “You cannot be only a melodist in music! There is something more than melody, than harmony - in fact, the music itself! .. ". Or in a letter from 1882: “Melody, harmony, recitation, passionate singing, orchestral effects and colors are nothing more than means. Make good music with these tools! .. ". In the heat of polemics, Verdi even expressed judgments that sounded paradoxical in his mouth: “Melodies are not made from scales, trills or gruppetto ... There are, for example, melodies in the bard's choir (from Bellini's Norma. M. D.), the prayer of Moses (from the opera of the same name by Rossini - M. D.), etc., but they are not present in the cavatins " Barber of Seville"," Magpies-thieves "," Semiramis "and so on. - What is it? “Anything you want, just not melodies” (from a letter from 1875.)

What caused such a sharp attack on Rossini's opera melodies by such a consistent supporter and convinced propagandist of national musical traditions Italy, what was Verdi? Other tasks that were put forward by the new content of his operas. In singing, he wanted to hear "a combination of the old with the new declamation", and in the opera - a deep and multifaceted identification of the individual traits of specific images and dramatic situations. This is what he was striving for, renewing the intonation structure of Italian music.

But in the approach of Wagner and Verdi to the problems of operatic drama, in addition to national differences, the other style orientation of artistic searches. Having started as a romantic, Verdi has emerged as the greatest master of realistic opera, while Wagner was and remains a romantic, although in his works from different creative periods, the features of realism appeared to a greater or lesser extent. This ultimately determines the difference between the ideas that worried them, the themes, the images, which made Verdi oppose Wagner's “ musical drama"Your understanding" musical stage drama».