The Pushkin Era in the Novel. "Eugene Onegin" as an encyclopedia of Russian life

Fashion and A.S. Pushkin ... The poet was a socialite, often visited high society, went to balls and dinners, took walks and clothes played an important role in his life. In the second volume of the "Dictionary of Pushkin's Language", published in 1956, you can read that the word "fashion" is used 84 times in Pushkin's works! And most of the examples the authors of the dictionary cite from the novel "Eugene Onegin". The fashion of the beginning of the 19th century was influenced by the ideas of the Great French Revolution, and France dictated fashion to the whole of Europe ... The Russian costume of nobles was formed in the mainstream of European fashion. With the death of Emperor Paul I, the bans on French costume collapsed. The nobles tried on a tailcoat, a frock coat, a vest.

Pushkin in the novel "Eugene Onegin" speaks with irony about the outfit of the protagonist:

“... I could before the learned light

Describe his outfit here;

Of course it would be bold

Describe my own business:

But pantaloons, tailcoat, vest,

All these words are not in Russian ... "

So what kind of outfits did the ladies and gentlemen of the time wear? The French fashion magazine Le Petit Courrier des Dames for the years 1820-1833 can help with this. The illustrations of clothing models from there just give an idea of what the people around him wore during the time of Pushkin.

The skill of creating dresses for men and women boggles our imagination. How can you make such splendor with your own hands, given that at that time there were not so many technical devices as now? How could these beautiful creations of skilled tailors be worn, given that they weighed much more than today's clothes?

The war of 1812 died down, but nevertheless, the most popular in culture in general, and in fashion in particular, by the 20s of the 19th century, was the Empire style. Its name comes from the French word "empire" and was inspired by the victories of Napoleon. This style is based on imitation of antique samples. The costume was designed in the same style as the columns, the high waist of women's dresses, a straight skirt, a corset that helps to better maintain the silhouette, created the image of a tall, slender beauty of ancient Rome.

“... Music roar, candles shine,

A flicker, a whirlwind of fast steam,

Beauties light hats.

Choirs dazzling with people,

Brides are a vast semicircle,

All the senses are suddenly struck ... "

Women's costume was complemented by a variety of different decorations, as if compensating for its simplicity and modesty: pearl threads, bracelets, necklaces, tiaras, feronnieres, earrings. Bracelets were worn not only on the hands, but also on the legs; almost every finger was decorated with rings and rings. Ladies' shoes, sewn from fabric, most often from satin, had the shape of a boat and were tied with ribbons around the ankle like antique sandals.

It is no coincidence that A.S. Pushkin dedicated so many poetic lines to female legs in Eugene Onegin:

"... Legs of lovely ladies fly;

In their captivating footsteps

Fiery eyes fly ... "

The ladies' toilet included long gloves, which were removed only at the table (and mitts - fingerless gloves - were not removed at all), a fan, a reticule (small purse) and a small umbrella that served as protection from rain and sun.

Men's fashion was permeated with the ideas of romanticism. In the male figure, the arched chest, thin waist, graceful posture were emphasized. But fashion gave way to the trends of the times, the requirements of business qualities, and enterprise. To express the new properties of beauty, completely different forms were required. Silk and velvet, lace, and expensive jewelry disappeared from clothing. They were replaced by wool, cloth of dark smooth colors.

Wigs and long hair are disappearing, men's fashion is becoming more stable, and English costume is gaining more and more popularity. During the 19th century, men's fashion was mainly dictated by England. It is still believed that London is for mens fashion what Paris is for womens.

Any secular man of that time wore a tailcoat. In the 20s of the XIX century, short pants and stockings with shoes were replaced by long and wide pantaloons - the predecessors of men's trousers. This part of the male costume owes its name to the character of the Italian comedy Pantalone, who invariably appeared on stage in long wide pants. The pantaloons were held on by the fashionable suspenders, and at the bottom they ended with stripes, which made it possible to avoid folds. Usually pantaloons and a tailcoat were of different colors.

Pushkin writes about Onegin:

"... Here is my Onegin at large;

Cut in the latest fashion;

How dandy London is dressed -

And finally I saw the light.

He is in French perfectly

I could express myself and write;

Easily danced the mazurka

And bowed at ease;

What is more to you? The light decided

That he's smart and very nice. "

Literature and art also influenced fashion and style. Among the nobility, the works of W. Scott gained fame, all those involved in literary novelties began to try on caged outfits and berets. Wanting to show Tatyana Larina's literary predilections, Pushkin dresses her in a new-fashioned beret.

This is what the scene at the ball looks like after Eugene Onegin returns to Moscow and where he meets Tatyana again:

"... The ladies moved closer to her;

The old ladies smiled at her;

The men bowed below

They caught the gaze of her eyes;

The girls passed quieter

In front of her in the hall: and all above

And he raised his nose and shoulders

The general came in with her.

Nobody could have her beautiful

Name; but from head to toe

No one could find in her

That which is an autocratic fashion

In the high London circle

It's called vulgar. (I can not...

"Really, - thinks Eugene, -

Is she really? But sure ... No ...

How! from the wilderness of the steppe villages ... "

And the obsessive lorgnette

He draws by the minute

The one whose appearance reminded vaguely

Forgotten features to him.

"Tell me, prince, do you not know,

Who is there in the crimson beret

Does the ambassador speak Spanish? "

The prince looks at Onegin.

- Aha! you haven't been in the world for a long time.

Wait, I'll introduce you. -

"Who is she?" - My Zhenya. -... "

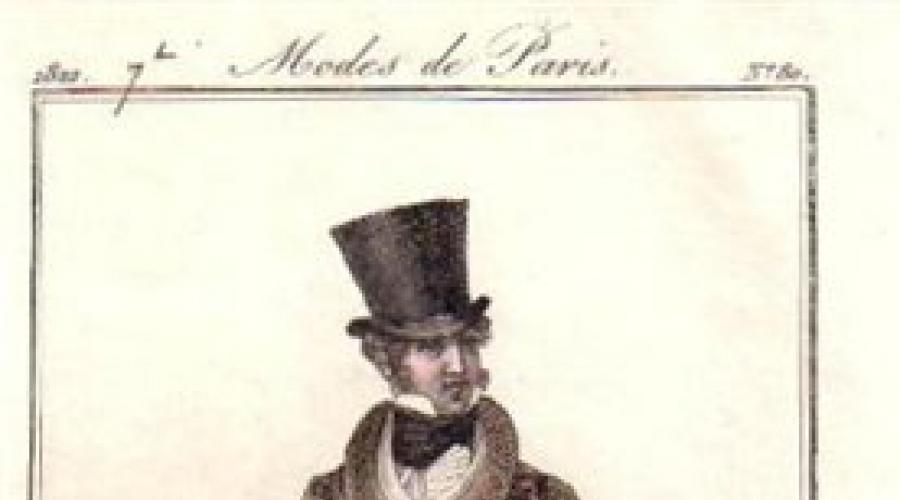

For men, the most common headdress of the Pushkin era was the top hat. It appeared in the 18th century and later changed color and shape more than once. In the second quarter of the 19th century, a wide-brimmed hat - bolivar, named after the hero of the liberation movement in South America, Simon Bolivar, came into fashion. Such a hat meant not just a headdress, it indicated the liberal public sentiment of its owner.Gloves, a cane and a watch were added to the men's suit. Gloves, however, were more often worn in the hands than on the hands, so as not to make it difficult to take them off. There were many situations when this was required. Good cut and quality material were especially appreciated in gloves.

The most fashionable thing in the 18th and early 19th centuries was a cane. The canes were made of flexible wood, which made it impossible to lean on them. They were worn in the arms or under the arm solely for panache.

In the second quarter of the 19th century, the silhouette of a woman's dress changes again. The corset comes back. The waistline dropped to its natural place, and the lacing was used. The skirt and sleeves have widened a lot to make the waist appear thinner. The female figure began to resemble an inverted glass in shape. Cashmere shawls, capes, boas were thrown over the shoulders, which covered the neckline. Accessories - umbrellas with frills in summer, in winter - clutches, handbags, gloves.

Here is how Pushkin says about it in Eugene Onegin:

"... The corset was very narrow

And Russian N, like N French,

She knew how to pronounce in the nose ... "

The heroes of A.S. Pushkin's novels and stories followed fashion and dressed in fashion, otherwise the respectable public would not have read the works of our Great Writer, he lived among people and wrote about what was close to people. And the insidious fashion, meanwhile, went on and on ...

You can be a smart person and think about the beauty of your nails!

A.S. Pushkin

![]()

DICTIONARY

names of clothes and toilet items used in the novel "Eugene Onegin"

Beret- soft, loose-fitting headgear. Who is there in the crimson beret // Speaks Spanish with the Ambassador?

Boa- women's wide shoulder scarf made of fur or feathers. He is happy if he throws // Boa fluffy on her shoulder ...

Bolivar- men's hat with very wide brim, kind of top hat. Putting on a wide bolivar, // Onegin goes to the boulevard ...

Fan- a small hand-held folding fan, unfolded in the shape of a semicircle, a necessary ladies' ballroom accessory.

Diadem- female head jewelry, origin. headdress of kings, and earlier - of priests.

Vest- short men's clothing without a collar and sleeves, over which a frock coat, tailcoat is put on. Here, noteworthy dandies seem to be // Their insolence, their vest ...

Carrick- men's winter coat, which had several (sometimes up to fifteen) large decorative collars.

Caftan- antique Russian men's clothing with a small collar or without it. In glasses, in a torn caftan, // With a stocking in his hand, a gray-haired Kalmyk ...

Necklace- Women's neck decoration with pendants in the front.

Corset- a wide elastic belt that covers the torso and under the dress tightens the waist. The corset was very narrow ...

Sash- a belt several meters long, to which various objects were fastened. The coachman sits on an irradiation // In a sheepskin coat, in a red sash ...

Lorgnette- optical glass, to the frame of which a handle is attached, usually folding. The double lorgnette leads with a bevel // On the lodges of unfamiliar ladies ...

Mac- a coat or raincoat made of rubberized fabric.

Trousers- men's long pants with strips without cuffs and smoothed pleats. But pantaloons, a tailcoat, a vest, // all these words are not in Russian ...

Gloves- a garment that covers the hands from the wrist to the end of the fingers and each finger separately.

Handkerchief- 1. garment - a piece of fabric, usually square, or a knitted product of this shape. With a handkerchief on her head, gray, // An old woman in a long quilted jacket ... 2. the same as a handkerchief. ... Or he will raise a handkerchief for her.

Readingot- women's and men's long fitted coat with a wide turn-down collar, buttoned up to the top.

Reticule- small handbag for women.

Coat- men's initially knee-length outerwear, deaf or with an open chest, with a stand-up or turn-down collar, at the waist, with narrow long sleeves.

Padded jacket- women's warm sleeveless sweater with gathers at the waist. With a headscarf on her head, gray, // An old woman in a long quilted jacket ...

Cane- straight thin stick.

Sheepskin coat- a long-brimmed fur coat, usually bare, not covered with cloth. The coachman sits on an irradiation // In a sheepskin coat, in a red sash ...

Feronniere- a narrow ribbon worn on the forehead with a gem in the middle.

Tailcoat- men's clothing, cut at the waist, with narrow long folds at the back and cut-out front hemlines, with a turn-down collar and lapels, often trimmed with velvet. But pantaloons, a tailcoat, a vest, // All these words are not in Russian ...

Robe- Household clothing, zipped or zipped from top to bottom. And he himself ate and drank in his dressing gown ...

Cylinder- a tall solid man's hat with a small firm brim, the upper part of which is in the shape of a cylinder.

Cap- a female headdress that covers the hair and is tied under the chin. Aunt Princess Helena // All the same tulle cap ...

Shawl- a large knitted or woven shawl.

Shlafor- home clothes, a spacious robe, long, without fasteners, with a wide wrap, belted with a lace with tassels. And finally updated // On cotton wool dressing gown and cap.

The end of the 10s -20s of the last century is often called the "Pushkin era". This is the heyday of that noble culture, which Pushkin has become a symbol of in our history. The influence of European enlightenment is replacing traditional values, but it cannot win. And life goes on in an amazing interweaving and confrontation between the old and the new. The rise of free-thinking - and the ritual of secular life, dreams of “becoming equal with the century” - and the patriarchal life of the Russian province, the poetry of life and its prose ... Duality.

The combination of good and bad in the peculiarities of noble life is a characteristic feature of the "Pushkin era".

In the novel "Eugene Onegin" we have an amazingly expressive and precise panorama of noble Russia. Detailed descriptions coexist with cursory sketches, full-length portraits are replaced by silhouettes. Characters, morals, way of life, way of thinking - and all this is warmed by the author's lively, interested attitude.

Before us is an era seen through the eyes of a poet, through the eyes of a person of high culture, high demands on life. Therefore, the pictures of Russian reality are imbued with sympathy

And dislike, warmth and aloofness. The novel created the author's image of the era, Pushkin Russia. There are features in it that are infinitely dear to Pushkin, and features that are hostile to his understanding of the true values of life.

Petersburg, Moscow and the provinces are three different faces of the Pushkin era in the novel. The main thing that creates the individuality and originality of each of these worlds is the way of life. It seems that even time flows in Russia in different ways: in St. Petersburg - quickly, and in Moscow - more slowly, in the provinces it is completely unhurried. The high society of St. Petersburg, the noble society of Moscow, the provincial landlord "nests" live, as it were, apart from each other. Of course, the lifestyle of the “hinterland” differs sharply from that of the capital, but in the novel the Moscow “roots” nevertheless stretch to the countryside, and the Petersburg resident Onegin turns out to be the Larins' neighbor. For all the individuality of the capitals and provinces, the novel ultimately created a single, integral image of the era, because in Moscow, in St. Petersburg, and in the hinterland there is noble Russia, the life of the educated class of Russian society.

Petersburg life appears before us brilliant and varied. And her paintings are not limited in the novel to criticism of secular ritual, a secured and meaningless existence. In the life of the capital, there is also poetry, the noise and splendor of “restless youth”, “seething passions”, a flight of inspiration ... All this is created by the presence of the author, his special sense of the world. Love and friendship are the main values of the author's “Petersburg” youth, the time he recalls in the novel. "Moscow ... how much of this sound has merged for the Russian heart!"

These famous Pushkin's lines are probably best of all critical articles capable of conveying the spirit of the ancient capital, the special warmth of its image in Eugene Onegin. Instead of Petersburg classical lines, the splendor of white nights, austere embankments and luxurious palaces, there is a world of churches, half of country estates and gardens. Of course, the life of Moscow society is no less monotonous than the life of the St. Petersburg world, and even devoid of the glitter of the northern capital. But in Moscow's customs there are those homely, patriarchal, primordially Russian features that soften the impression of "drawing rooms". For the author, Moscow and the city that did not submit to Napoleon is a symbol of Russian glory. In this city, a person involuntarily wakes up a national feeling, a sense of his involvement in national destiny.

And what about the province? I live there and not at all in a European way. The life of the Larin family is a classic example of provincial simplicity. Life is made up of everyday sorrows and everyday joys: household, holidays, mutual visits. Tatyana's name days differ from peasant name days, probably, only by the treat and the character of the dances. Of course, even in the provinces, monotony can “capture” a person, turn life into existence. An example of this is the uncle of the protagonist. But all the same, how much in the rustic simplicity is attractive, how much charm! Solitude, peace, nature ... It is no coincidence that the author begins to dream of "old days", of new literature dedicated to unassuming, natural human feelings.

The Pushkin era is now remembered as the “golden age” of Russian culture. The complex, dramatic features of the "Alexander" time seem almost imperceptible, receding before the magic of Pushkin's novel.

Essays on topics:

- During the Great Patriotic War M. Isakovsky wrote one of his best works - the poem "Russian Woman", creating in it ...

Arise, prophet, and see, and hearken,

Fulfill my will

And, bypassing the seas and lands,

Burn the hearts of people with the verb.

A.S. Pushkin

Two feelings are marvelously close to us -

In them, the heart finds food -

Love for the native ashes,

Love for fatherly coffins.

A.S. Pushkin

"Peter (. - L. R.) threw a challenge to Russia, to which she responded with a colossal phenomenon" - these words of A. I. Herzen are not an exaggeration. Only by the beginning of the 19th century. In Russian artistic culture, there have been striking changes caused by the beginning of a dialogue between two powerful Russian cultural traditions. The first of them, ancient, folk, was born at the end of the 10th century. in the depths of spirituality and is illuminated by the names of Anthony Pechersky, Dmitry Rostovsky, Seraphim Sarovsky. The second is official, noble, young, but already having a rich experience of "Russian Europeanness" in the 18th century. Their dialogue (but in the expression of DS Likhachev, "the combination of various heritage") was not direct and immediate.

Suffice it to recall that many noblemen of the Pushkin era, and even Alexander Sergeevich himself, were not even familiar with their great contemporary, prayer for the Russian land, Elder Seraphim of Sarov (1760-1833). We are talking about something else: from the beginning of the XIX century. Russian secular culture, and above all art culture, acquired features of maturity. Russian masters have learned to embody in artistic images all those ideas and ideals that were nurtured by the Russian people throughout its Orthodox history. Therefore, the Christian foundations of art in the first half of the 19th century. can be traced in everything: both in the desire for knowledge of the high truths and laws of Being, and in the desire to understand and reflect in artistic images the suffering and misery of a simple, disadvantaged person, and in a passionate protest against lies, hatred, and injustice of this world.

And also - in the inescapable love for Russia, for its endless expanses, for its long-suffering history. And finally, in the piercing theme of the responsibility of the artist-creator, the artist-prophet to the people for each of his works. In other words, the centuries-old Orthodox spirituality formed an unwritten moral code among Russian artists, composers, and writers, which became the main reference point in the creative search for “their own way” in the art of the Pushkin era and in the decades that followed. In conclusion of this short preamble to the main content of the section, I would like to compare the statements of the two great sons of Russia. “Acquire the spirit of peace,” called Elder Seraphim of Sarov. “And revive the spirit of humility, patience, love and chastity in my heart,” AS Pushkin wrote shortly before his death. In the history of Russian artistic culture, the 19th century is often called the "golden age", marked by the brilliant development of literature and theater, music and painting. The masters of the "golden age" made a rapid breakthrough to the heights of creativity in the most complex European forms and genres, such as novel, opera and symphony. The "Russian Europeanness" of the 18th century has become a thing of the past, along with the outdated colloquial vocabulary and powdered wigs of Catherine's times. To replace the creators of the classicist art of the Enlightenment, the “defeated teachers” - Derzhavin and Levitsky, Bazhenov and Bortnyansky - a new generation of Russian artists - “winner-pupils” - was in a hurry. AS Pushkin (1799-1837) is rightfully considered the first among them.

The Pushkin era, i.e. the first three decades of the "golden age" are the "beginning of the beginnings" of the achievements, discoveries and revelations of the great Russian classics, an impulse that predetermined the further cultural development of Russia. The result of this movement is the rise of art to the level of high philosophy, spiritual and moral teachings. The problems of the Divine and the earthly, life and death, sin and repentance, love and compassion - all this took on an artistic form, capturing the complex, extraordinary world of a Russian person who is not indifferent to the fate of the Fatherland and is trying to solve the most acute problems of Being. The creators of the Pushkin era laid the main thing in the Russian classics - its teaching, moral and educational character, its ability to embody everyday reality, without contradicting the eternal laws of beauty and harmony. The Pushkin era was marked by two significant events for Russia - the Patriotic War of 1812 and the Decembrist uprising of 1825. These upheavals did not pass without a trace. They contributed to the ripening in the Russian public consciousness of protest sentiments, a sense of national dignity, civic patriotism, love of freedom, which often came into conflict with the age-old foundations of the autocratic state. Brilliant in its artistic merit, the realistic comedy of A. S. Griboyedov "Woe from Wit", depicting the opposition of "one sane person" from among the educated "non-whipped generation" (A. Herzen) of the Russian nobility and the conservative nobility is convincing proof of this.

In the midst of the seething polyphony of ideologies, views, attitudes, a phenomenon was born and took place, which today we call the "genius of Pushkin." Pushkin's work is a symbol of Russian art for all times. His poetry and prose deeply and multifaceted captured the national spiritual experience and traditional moral values of the Russian people. At the same time, Pushkin's unique ability to feel world culture as a single whole in space and time is obvious and to respond to the echoes of previous centuries with all his inherent “universal responsiveness” (F. M. Dostoevsky). Here it should be reminded once again that it was Pushkin, according to many researchers, who managed “to overcome the duality of Russian culture, to find the secret of combining its opposite principles. The synthesis of deeply national and truly European content in his work occurs extremely naturally. His fairy tales were read both in the living rooms of the nobility and in the peasant huts. With the works of Pushkin, Russian self-awareness entered the vast world of new European culture.<…>The "Golden Age" of Russian culture bears a distinct imprint of the Pushkin style. This allows us to conditionally designate the type of this cultural era as the "Pushkin" model of Russian culture ”1. Perhaps more has been written about Pushkin the writer than about any other Russian genius 2. Therefore, let's move on to considering the phenomena of artistic culture that arose in the depths of the Pushkin era. V.F. Odoevsky named A.S. Pushkin "the sun of Russian poetry."

To paraphrase these words, MI Glinka (1804-1857), the founder of the Russian classical music school, can be called "the sun of Russian music." By the power of his genius, Glinka was the first to bring the musical art of Russia into one of the most significant phenomena of world culture. He approved the principles of nationality and national character in Russian music, organically linking the achievements of European art with Russian folk song. The composer's artistic credo can be considered his words: "... the people create music, and we, composers, only arrange it." The people are the main hero of his works, the bearer of the best moral qualities, dignity, and patriotism. The expression of the nationality was the melodious Glinka melody, sincere, direct, which grew out of the deep layers of Russian musical folklore. Each voice in the musical fabric of his works sings in its own way, obeying the logic of general development. Glinkinskaya chanting makes his music akin to folk song, makes it nationally colored and easily recognizable. At the same time, the composer was inexhaustiblely inventive in the variant development of musical themes. This composer's method, also "overheard" in Russian folk song, becomes "significant" for Russian classical music of the 19th century. Anyone who listens to Glinka's music cannot escape the parallel between Glinka and Pushkin. This comparison is inevitable: Pushkin's poetry sounds both in Glinka's romances and in his opera Ruslan and Lyudmila. Both masters were the founders and discoverers of the "golden age". Like Pushkin's poetry, Glinka's music embodies a healthy life principle, the joy of being, an optimistic perception of the world. This relationship is complemented by the "universal responsiveness" that is equally inherent in both the poet and the composer. Glinka was close to the temperamental tunes of the East, the graceful grace of Polish dances, the most complex melodic lines of Italian opera arias, passionate Spanish rhythms. Listening to the world of foreign-language musical cultures, the composer, like a diligent collector, collected priceless musical treasures of different nations and refracted them in his work. These are the magnificent Polish scenes in the opera A Life for the Tsar, and the images of Russian Spain in the Spanish Overtures for the symphony orchestra, and the Russian East in the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila. Opera is central to Glinka's legacy. The composer laid the foundations for two leading opera genres in Russian classical music - opera-drama and epic opera-fairy tale. Glinka called his opera A Life for the Tsar (1836) “the national heroic-tragic”.

The essay, based on real events in Russian history at the beginning of the 17th century, is devoted to a deeply patriotic theme: the village head Ivan Susanin dies, at the cost of his life saving the royal family from the reprisals of the Polish invaders. For the first time in Russian music, the main character of an opera composition is the common people - the bearer of high spiritual qualities, goodness and justice. In the mass folk scenes that frame the opera, the introduction (from the Latin introductio - introduction) and the epilogue, where Glinka composed the grandiose hymns of Russia, stand out. The famous choir "Glory", which the composer called "anthem-march", sounds victorious and solemn in the finale of the opera. Glinka endowed the main tragic character of the opera - the peasant Ivan Susanin with the real features of a Russian farmer - a father, a family man, a master. At the same time, the image of the hero has not lost its greatness. According to the composer, Susanin draws spiritual strength for selfless feat from the source of the Orthodox faith, from the moral foundations of Russian life. Therefore, in his part, themes taken from folk scenes are heard. Pay attention: Glinka almost never uses genuine folk songs in the opera: he creates his own melodies that are close in intonation to folk musical speech.

However, for the first appearance on the stage of Ivan Susanin, the composer nevertheless took a real folk tune - a melody recorded from a Luga cabman (in the opera, Susanin's remark: “What to guess about a wedding”). It is no coincidence that the composer's enemies after the successful premiere of the opera dubbed it "coachman's". But on the other hand, A.S. Pushkin responded to Glinka's creation with a magnificent impromptu: Listening to this novelty, Envy, darkening with malice, Let it grind, but Glinka cannot be trampled into the mud. Another peak in the work of MI Glinka is the opera "Ruslan and Lyudmila" (1842) based on the youthful poem by Alexander Pushkin. The composer hoped that Pushkin would write the libretto himself, but the poet's untimely death ruined this beautiful plan. Without changing the outline of Pushkin's text, Glinka made some adjustments to it: he removed the touch of irony and playfulness and endowed the main characters - Ruslan and Lyudmila - with deep, strong characters.

Some changes are related to the specifics of the opera genre. So, for example, if Pushkin's princely feast in Kiev occupies all seventeen lines of poetry, then Glinka turned this holiday into a grandiose musical scene, magnificent and magnificent. "Ruslan and Lyudmila" is an epic opera, which means that the conflict in it is revealed not through a direct clash of opposing forces, but on the basis of the unhurried development of events captured in completed paintings with strict logic. The introduction and finale that frame the opera appear as stately frescoes of ancient Slavic life. Between them, the composer placed contrasting magical acts, reflecting the adventures of the heroes in the kingdom of Naina and Chernomor. In "Ruslana and Lyudmila" the features of an epic, a fairy tale and a lyric poem are combined, therefore, heroic, lyrical and fantastic lines can be distinguished in the music of the opera. The heroic line opens with Bayan's songs in the introduction of a musical work and continues in the development of the image of the noble warrior Ruslan. The lyrical line is the images of love and fidelity. She is presented in the arias of Lyudmila, Ruslan, in the ballad of Finn. The bright characters of the opera are contrasted with "evil fantasy" - the powers of magic, sorcery, oriental exoticism.

In fantastic scenes, the composer used colorful, unusual-sounding means of orchestral expressiveness and genuine folk themes that exist in different regions of the Caucasus and the Middle East. The opera's antiheroes do not have developed vocal characteristics, and the evil Chernomor is a dumb character at all. The composer did not deprive the magical evil of Pushkin's humor. The famous "March of Chernomor" conveys the features of a formidable but funny Karla, whose fairy-tale world is illusory and short-lived. Glinka's symphonic heritage is small in volume. Glinka's orchestral masterpieces include Waltz-Fantasy, Kamarinskaya, Aragonese Jota, Memories of a Summer Night in Madrid, whose music contains the main principles of Russian classical symphony. A special area of the composer's creativity is "Pushkin romances": "I am here, Inesilla", "Night marshmallow", "The fire of desire burns in the blood", "I remember a wonderful moment" and many other Pushkin lines have found surprisingly sensitive and expressive embodiment in magical sounds Glinka. The process of the organic combination of two cultural traditions - deep national and European - was vividly reflected in the visual arts. Russian countryside, the life of peasants and ordinary townspeople - these are the images of the paintings of the outstanding masters of the Pushkin era A.G. Venetsianov and V.A. Tropinin. The works of A.G. Venetsianov (1780-1847) bear traces of classicist ideas about the lofty ideals of harmonious beauty. When, by the decision of Emperor Alexander I, an exhibition of Russian artists was opened in the Winter Palace, Venetsianov's canvases took pride of place in it. This is no coincidence. A remarkable master, Venetsianov is rightfully considered the ancestor of a promising new genre of genre in Russian painting. The son of a Moscow merchant, A.G. Venetsianov, in his youth, worked as a draftsman and land surveyor, until he realized that his true vocation was painting.

Having moved from Moscow to Petersburg, he began to take lessons from the famous portrait painter V.L. Borovikovsky and quickly established himself as the author of classicist ceremonial portraits. The turn in his creative life happened unexpectedly. In 1812, the artist acquired a small estate in the Tver province, where he settled. The peasant life amazed and inspired the master on completely new themes and subjects. Villagers peeling beets, scenes of plowing and harvesting, haymaking, a shepherd asleep by a tree - all this appears on the artist's canvases as a special poetic world, devoid of any contradictions and conflicts. There is no plot development in the "quiet" paintings of A. G. Venetsianov. His works are fanned by the state of eternal prosperity and harmony between man and nature. The beauty of the touching, skillfully done by the painter always emphasizes the spiritual generosity, dignity, nobility of a simple farmer, forever connected with his native land, with its ancient traditions and foundations ("Sleeping Shepherd", 1823 - 1824; "On arable land. Spring", 1820s .; "At the harvest. Summer", 1820s; "Reapers", 1820s).

Equally calm and harmonious is the inner world of the heroes of paintings by VA Trolinin (1776-1857), a remarkable Moscow master of portrait painting. Tropinin achieved fame, success, the title of academician thanks to his enormous talent and ability to follow his life vocation, despite the obstacles prepared by fate. A serf, Tropinin almost to old age served as a lackey for his masters, and received his freedom only at forty-five years old under pressure from the public, being already a famous artist. The main thing that the master managed to achieve was to establish his artistic principles, where the main thing is the truth of the environment and the truth of character. The heroes of Tropinin's paintings feel at ease and at ease. Often absorbed in the usual work, they seem to not notice the close attention to them. Numerous "Lacemakers", "Gold Embroiderers", "Guitarists" say that Tropinin, like Venetsianov, somewhat idealized his models, highlighting sparks of reasonable beauty and goodness in everyday life. Among the artist's works, a special place is occupied by images of people of art, devoid of any ceremonial bombast, attracting with their rich inner content. Such are the portraits of A.S. Pushkin (1827), K.P.Bryullov (1836), a self-portrait against the background of a window overlooking the Kremlin (1844), "Guitarist" (portrait of the musician V.I.Morkov, 1823). Even during the life of AS Pushkin, the words “Great Karl”, uttered by someone from his contemporaries, could mean only one thing - the name of the genius artist KP Bryullov (1799-1852).

None of the masters of Russia had such fame then. It seemed that everything was given to Bryullov too easily. However, behind a light brush was hidden inhuman labor and a constant search for unbeaten paths in art. Take a look at the famous "Self-portrait" (1848). Before us is an extraordinary person, confident in himself and his professionalism, but at the same time immensely tired of the burden of fame. KP Bryullov's works captivated the audience with the brilliance of temperament, a sense of form, and the dynamics of rich color. A graduate of the Academy of Arts, Bryullov, already in his first paintings, declared himself as an independent master, alien to the closed academism. He knew the canons of classicism well, but as needed he freely overcame them, filling artistic images with a sense of living reality.

In 1821, Bryullov was awarded the Small Gold Medal of the Academy of Arts for the painting "The Appearance of Three Angels to Abraham by the Oak of Mamvri". However, the leadership of the Academy unexpectedly denied the master a pension for a trip abroad (apparently, the refusal was due to the conflict of a quarrelsome young man with someone from the higher teaching staff). Only the Society for the Encouragement of Artists allocated money for a business trip abroad. But Bryullov soon learned how to earn his living. The purpose of his voyage was traditional - Italy. The way to her lay through Germany and Austria, where Bryullov in a short time acquired a European name as a master of portrait. Orders literally poured in from all sides.

At the same time, the artist was extremely demanding of himself and never worked only for the sake of money. He did not complete all the canvases, sometimes throwing the canvas, which he ceased to like. The rich colors of Italian nature awakened Bryullov's desire to create "sunny" canvases. Such magnificent works as "Italian morning" (1823), "Girl picking grapes in the vicinity of Naples" (1827), "Italian noon" (1827) are imbued with the mood of admiration for the beauties of the world. The artist worked with inspiration and quickly, although sometimes he nurtured his ideas for a long time. So, in 1827, he first visited the ruins of Pompeii, a city near Naples, which died from the eruption of Vesuvius in 79. The picture of the tragedy struck the artist's imagination. But only a few years later, in 1830, he took up the painting "The Last Day of Pompeii", completing it three years later. Two figurative spheres converged in the picture. The first is a formidable element, beyond the control of man, a fatal retribution for his sins (recall that, according to legend, Pompeii and Herculaneum were punished by God as cities of debauchery, as a place for sexual entertainment for wealthy Romans) 1. The second is the image of humanity, sacrifice, suffering and love. Among the heroes of the canvas are those who save the most precious things in these terrible moments - children, father, bride. In the background, Bryullov depicted himself with a box for paints.

This character is full of close attention to the unfolding tragedy, as if preparing to capture it on canvas. The presence of the artist tells the audience: this is not a figment of the imagination, but the historical testimony of an eyewitness. In Russia, the painting "The Last Day of Pompeii" was officially recognized as the best painting of the 19th century. A laurel wreath was laid on the artist to an enthusiastic ovation, and the poet E. A. Baratynsky responded to the master's triumph with verses: And it became "The Last Day of Pompeii" For the Russian brush, the first day. Beautiful human bodies and faces have always attracted KP Bryullov, and many of his characters are unusually beautiful. During his last years in Italy, he wrote the famous Horsewoman (1832). On the canvas is a magnificent lady, riding a hot horse with the dexterity of an Amazon. A certain conventionality of the appearance of the prancing beauty is overcome by the liveliness of the girl who ran out to her (the sisters of Paccini, the daughter of the Italian composer, who were brought up in the house of the childless Countess Yu.P. Samoilova, posed for the master).

No less beautiful is the portrait of Y.P. Samoilova herself with her pupil Amatsilia Paccini (c. 1839). There is a sense of admiration for the beauty of the model dressed in a luxurious fancy dress. So, literature, music, painting of the Pushkin era, with all the diversity of their images, speak about one thing - about the stormy self-identification of Russian culture, about the desire to assert Russian national spiritual and moral ideals on the "European field". In those years, no philosophical substantiation of the “Russian idea” was found, but artistic traditions have already appeared that develop the idea of the values of Russian statehood, the significance of Russian military victories, overshadowed by the banners of the Orthodox faith.

So, back in 1815, on the crest of popular jubilation over the victory over Napoleon, poet VA Zhukovsky wrote "The Prayer of the Russians", beginning with the words "God Save the Tsar", which was originally sung on the theme of the English anthem. In 1833, the composer A.F. Lvov (on behalf of A.H. Benkendorff) created a new melody, which made it possible to approve the "Prayer of the Russians" as the military and official anthem of Russia. But, perhaps, the most vividly of all the ideals of the heroic time and the increased Russian self-awareness were embodied in architecture. Images of architecture of the first decades of the 19th century. amaze with their regal splendor, scope and civic pathos. Never before has the construction of St. Petersburg and Moscow, as well as many provincial cities, acquired such a grandiose scale. Achievements of architecture, unlike other arts, are associated with a new stage in the development of classicism, which is called "high", or "Russian", Empire style. Classicism of the XIX century. was not a "repetition of the past", he discovered many original, innovative architectural ideas that meet the needs of his contemporaries. And although the Empire style came to Russia from Europe, it can be argued that it received its most striking development only on Russian soil.

In terms of the number of masterpieces of this style, St. Petersburg may well be considered a kind of museum collection of 19th century architectural classicism. The main feature of the Russian Empire style is the organic synthesis of architecture, sculpture and arts and crafts. The aesthetic understanding of construction tasks has also changed: now each city building was not closed in itself, but was inscribed in the neighboring buildings compositionally and logically, with the exact calculation of creating "stone beauty". The structure determined the appearance of the square, and the square - the nearby urban structures: such a chain was born in the projects of the early 19th century. This is how the ensembles of the main squares of St. Petersburg are formed - Dvortsovaya, Admiralteyskaya, Senatskaya. Moscow, which was badly damaged by the fire of 1812, is not lagging behind in updating its appearance: the territory around the Kremlin is being rebuilt, Red Square is being rebuilt, Teatralnaya is being broken up, new squares are emerging at the intersection of ring and radial roads, old houses are being restored, new mansions, public places, trading ranks.

The founder of high Russian classicism was A. N. Voronikhin (1759-1814). The main work of his life was the construction of the Kazan Cathedral in St. Petersburg (1801-1811). A competition for the design of this building was announced during the reign of Paul I. It is known that the emperor wanted to build a temple in Russia like the Roman Cathedral of St. Peter, but Voronikhin proposed a different solution. And he won the competition! The architect conceived the cathedral as a palace with a large colonnade covering the "body" of the temple itself. The colonnade formed a semicircular square on Nevsky Prospekt, the main street of St. Petersburg. It consists of 94 columns of the Corinthian order with a height of about 13 meters, directly "flowing" into the city (by the way, this is the only similarity with St. Peter's Cathedral, agreed with Paul I). Despite its huge volumes, the Kazan shrine seems weightless. The impression of lightness, free, as it were, open space is retained when entering inside. Unfortunately, painting and luxurious sculptural decoration, created under Voronikhin, have not reached us completely. Kazan Cathedral immediately took a special place in the public life of Russia. It was here, on the Cathedral Square, that the people bid farewell to MI Kutuzov, who was leaving for the army to fight Napoleon. It is here, in the cathedral, that the field marshal will be buried, and A.S. Pushkin, having visited the grave, will dedicate the famous lines to the commander: Before the tomb of the saint I stand with a drooping head ...

Everything is asleep all around; some lamps In the darkness of the temple granite masses of columns gilded And their banners overhanging a row.<…>Delight lives in your coffin! He gives us a Russian voice; He repeats to us about that time, When the voice of the people called out to your holy gray hair: "Go, save!" You got up - and saved ... And today on the wall near the holy tomb hang the keys from the enemy cities conquered by the Russian army in the war of 1812. Later, on both sides of Kazan Square, monuments to M.I.Kutuzov and M. B. Barclay de Tolly were erected - this is how Russia immortalized the memory of its heroes. A. N. Voronikhin could no longer see all this - he died in February 1814, when our troops were just approaching Paris. “To stand firm by the sea ...” - this is how Pushkin formulated the dream of Peter the Great, the founding father of the northern capital. This plan began to be realized during the life of the emperor. But it was fully realized only by the 19th century. A hundred years have passed, and the young city of the full-night countries is a beauty and wonder, From the darkness of the forests, from the swamp of cronyism, Ascended magnificently, proudly.<…>Along the busy shores of the Hromada slender palaces and towers are crowded; ships Crowd from all corners of the earth Aspire to rich marinas; The Neva was dressed in granite; Bridges hung over the waters; The islands were covered with Her dark green gardens ... Pushkin, as always, was very accurate in describing the new, European in appearance, but Russian in essence, the city.

The basis of the layout of St. Petersburg was determined by the river - capricious, bringing a lot of trouble during floods, but full-flowing, accessible for ships of all sizes. During the navigation period from the time of Peter the Great, the port was located at the eastern end of Vasilievsky Island in front of the famous building of the Twelve Collegia. There was also the Exchange, unfinished in the 18th century. The talented Swiss architect Tom de Thomon (1760-1813) was entrusted with the erection of the building of the new Stock Exchange (1805-1810). The exchange was located on the spit of Vasilyevsky Island, washed on the sides by two channels of the Neva. The architect completely changed the look of this place, turning it into an important point of the ensemble of the center of St. Petersburg. A semicircular square has formed in front of the main facade of the Stock Exchange, allowing you to admire the clear, compact composition of the building with unusually simple and powerful geometric shapes. The houses to the right and left of the Stock Exchange were built after the death of the architect by his followers. Equally important for the formation of the complete look of the center of St. Petersburg was the construction of the Admiralty (1806-1823), designed by the Russian architect A.D. Zakharov (1761-1811). Let's remind that the main idea of this building belonged to Peter 1.

In 1727-1738. the building was rebuilt by I.K. Korobov. The work of A.D. Zakharov became the highest point in the development of late classicism. The Admiralty appears as a monument to the glory of the Russian capital, as its symbol and at the same time as the most important part of the city. Construction began with the renovation of the old building, but then Zakharov went far beyond the original task and designed a new composition, while preserving the famous Korobov spire. The main facade of the Admiralty stretched along the resulting square, and the side facades of the general U-shaped configuration turned out to be directed towards the Neva. Zakharov believed: the Admiralty needs a sculptural decoration that matches the image. Therefore, he himself drew a detailed plan for the location of the sculptures, which was later implemented by remarkable Russian masters - FF Shchedrin, II Terebenev, VI Demut-Malinovsky, SS Pimenov and others. The selection of subjects for the sculptures was determined by the function of the building - the main naval department of the then Russia. Here are the deities who control the water elements, and the symbolism of rivers and oceans, and historical scenes on the themes of the construction of the fleet and the exploits of Russian sailors. Among the most expressive sculptural decorations is the stucco frieze1 "Establishment of the Fleet in Russia", created by the master II Terebenev.

Thus, the Admiralty became a tribute to the memory of the deeds of Peter the Great, who made Russia a powerful naval power. In the first decades of the XIX century. preference in architecture is given to buildings of a public or utilitarian nature. Theaters and ministries, departments and regimental barracks, shops and horse yards - all this is being erected relatively quickly, efficiently and in the best traditions of Russian high classicism. It should be borne in mind that many buildings of seemingly practical purpose acquired the symbolism of monuments that glorify Russia (such as the Admiralty).

The victory in the Patriotic War of 1812 stirred up a sense of patriotism, national pride and a desire to perpetuate the feat of arms of Russian soldiers in society. The field of Mars, famous today all over the world, was once a swamp. Then, in Peter's times, it was drained and a palace was built for Empress Catherine I. Tsaritsyn Meadow, as these once perilous lands began to be called, turned into a favorite pastime of Petersburgers: they had fun and let fireworks here, so over time the meadow was nicknamed the Amusing Field.

After the war with Napoleon, the square was renamed the Field of Mars (Mars is the god of war). Now military parades and reviews were held here, and the field became associated with military glory. In 1816, the barracks of the Pavlovsky regiment began to be erected on the Field of Mars. The elite Life Guards Pavlovsky regiment was a living legend, the embodiment of courage and valor. Therefore, for the Pavlovian grenadiers, it was necessary to create something worthy, solid and extraordinary. The work was carried out according to the project of the native Muscovite, architect V.P. Stasov (1769-1848), to whom the northern capital owes many wonderful architectural creations. Pavlovsk barracks is a strict, solemn and somewhat austere structure, which surprisingly accurately meets their purpose. "Restrained majesty" - this is how Stasov himself appreciated the image of the barracks.

The master retains this style in his other works as well. Another significant building rebuilt by Stasov, the Imperial Stables (1817-1823), adjoins the Field of Mars. The architect turned the inexpressive century-old building into a true work of art, making it the center of the organized around the square. This place has a special meaning for us: in the gate church on Konyushennaya Square on February 1, 1837, A.S. Pushkin was buried. A special area of creativity V.P. Stasov - regimental churches and cathedrals. The architect built two wonderful cathedrals in St. Petersburg for the Preobrazhensky and Izmailovsky regiments. The regimental church in the name of the Holy Trinity (1827-1835) was erected on the site of the wooden church of the same name, which had fallen into disrepair. Proposing to Stasov the development of the project, the customers specially stipulated the conditions: the new church must accommodate at least 3000 people and have exactly the same arrangement of the chapters as in the old church. The condition was fulfilled, and the stately, snow-white, handsome temple ascended over the capital with its light blue domes, on which golden stars shone. By the way, this is how temples were decorated in Ancient Russia, and Stasov knew his native well. Spaso-Preobrazhensky Cathedral (1827-1829) was also not created from scratch: during its construction, the architect had to use the construction of this

the middle of the 18th century, which was badly damaged by fire. The end of construction work coincided with the victory in the Russian-Turkish war (1828-1829). In memory of this event, V.P. Stasov built an unusual fence around the temple, made up of captured Turkish cannons. On the fifteenth anniversary of the Battle of Borodino, the ceremony of laying the Triumphal Gate was held at the Moscow Outpost - the beginning of the journey from St. Petersburg to the old capital. The project of the triumphal building belonged to Stasov and was conceived as a monument to Russian military glory. The gate consists of twelve Doric columns, fifteen meters high. A heavy entablature rests on the columns. Above the pairs of extreme columns, there are eight compositions of copper: intertwined armor, spears, helmets, swords, banners, symbolizing the exploits and triumph of Russian weapons. The cast-iron composition was crowned with the inscription: "To the victorious Russian troops", then the feats accomplished in 1826-1831 were listed. The first among equals in Russian architecture in the 1810s - 1820s. KI Rossi (1775-1849) is rightfully considered. In an era when Russia was inspired by the triumph of its victories, Rossi developed the principles of grandiose ensemble urban planning, which became a model for other masters. And it was at this time that Rossi realized all his ingenious creative plans.

The master thought outside the box and on a large scale. Receiving an order for a project of a palace or a theater, he immediately expanded the framework of construction, creating new squares, squares, and streets around the building being erected. And each time he found special methods of harmonious correlation of the building with the general appearance of the area. For example, during the construction of the Mikhailovsky Palace (now the State Russian Museum), a new square was laid out, and a street was laid from it, connecting the palace with Nevsky Prospekt. It was Rossi who gave the Palace Square a finished look, building the IT in 1819-1829. the building of the General Staff and the ministries and throwing a wide arch between the two buildings. As a result, the irregular, from the point of view of high classicism, the shape of the Palace Square, inherited from the 18th century, acquired a regular, harmonious and symmetrical character. In the center of the entire composition there is a triumphal arch crowned with six horses with warriors and a chariot of glory.

One of the most beautiful creations of K. I. Rossi is the Alexandria Theater (1816-1834). In connection with its construction, the appearance of the nearest buildings has changed beyond recognition. Rossi organized the square and cut new streets, including the famous street with symmetrical buildings that now bears his name. The architect had a strong character and an outstanding ability to defend his ideas, which he thought through to the smallest detail. It is known that he supervised all the work on the decoration of buildings, he himself made projects for furniture, wallpaper, closely followed the work of sculptors and painters. That is why its ensembles are unique not only in terms of architectural composition, but also as an outstanding phenomenon of the synthesis of the arts of high classicism. The last creations of the architect - similar to the palaces of the Synod and the Senate (1829-1834), completing the ensemble of the Senate Square, where the famous "Bronze Horseman" E. M. Falcone is located.

In the heritage of Russia there is another creation that is not directly related to architecture, but has a huge historical, spiritual and moral significance. This is the Military Gallery dedicated to the memory of the heroes of the Patriotic War, which adorned one of the interiors of the Winter Palace. The gallery contains 332 portraits of prominent Russian military leaders. A.S. Pushkin wrote: The Russian Tsar has a chamber in his palaces: It is not rich in gold, not in velvet;<…>In a crowded crowd, the artist placed Here the leaders of our people's forces, Covered with the glory of a wonderful campaign And the eternal memory of the twelfth year. Moscow, in a hurry to renew its appearance after the fire of 1812, adopted the new ideas of high classicism, but at the same time retained many traditional forms.

The combination of the new and the old gives Moscow architecture a special uniqueness. Among the architects who carried out the reconstruction of the ancient capital, the name of OI Bove (1784-1834) stands out. It was he who first tried to combine the medieval buildings of Red Square with a new building - the Trading Rows (1815, later dismantled). The low dome of the Trading Rows was directly opposite the dome of the Kazakov Senate, visible from behind the Kremlin wall. On this formed axis, a monument to Minin and Pozharsky, the heroes of 1612, made by the sculptor I.P. Martos (1754-1835) was erected, with its back to the rows. Bove's most famous creation is the Triumphal Gates, erected at the entrance to Moscow from the St. Petersburg side (1827–1834; nowadays they have been moved to Kutuzovsky Prospekt). A monumental arch crowned with six horses echoes the images of St. Petersburg architecture and complements the panorama of the grandiose monuments of Russian architecture that glorified Russia and its victorious army.

Rapatskaya L.A. History of the artistic culture of Russia (from ancient times to the end of the XX century): textbook. manual for stud. higher. ped. study. institutions. - M .: Publishing Center "Academy", 2008. - 384 p.

Panorama of Russian culture. Literature is the face of culture. Romantic philosophy of art. Humanistic ideals of Russian culture. Creative contradictions of the Pushkin era. Pushkin Pleiad. Three secrets of Pushkin.

The first decades of the 19th century in Russia took place in an atmosphere of social upsurge associated with the Patriotic War of 1812, when among educated Russian people a sense of protest against the existing order of things was ripening. The ideals of this time found expression in the poetry of the young Pushkin. The war of 1812 and the Decembrist uprising largely determined the character of Russian culture in the first third of the century. V.G. Belinsky wrote about 1812 as an era from which "a new life for Russia began," emphasizing that it is not only "in the external greatness and splendor", but above all in the internal development in society of "civic consciousness and education", which are " the result of this era ”. The most important event in the social and political life of the country was the uprising of the Decembrists, whose ideas, struggle, even defeat and death influenced the mental and cultural life of Russian society.

Russian culture in this era is characterized by the existence of various trends in art, successes in science, literature of history, i.e. we can talk about the panorama of our culture. In architecture and sculpture, mature, or high, classicism dominates, often coiled by the Russian Empire style. The success of painting, however, lay in a different direction - romanticism. The best aspirations of the human soul, the ups and downs of the spirit were expressed by the romantic painting of that time, and above all by the portrait, where outstanding achievements belong to O. Kiprensky. Another artist, V. Tropinin, with his work contributed to the strengthening of realism in Russian painting (suffice it to recall his portrait of Pushkin).

The main direction in the artistic culture of the first decades of the 19th century. - romanticism, the essence of which is to oppose the reality of the generalized ideal image. Russian romanticism is inseparable from the general European, but its feature was a pronounced interest in national identity, national history, the establishment of a strong, free. personality. Then the development of artistic culture is characterized by a movement from romanticism to realism. In literature, this movement is especially associated with the names of Pushkin, Lermontov, Gogol.

In the development of Russian national culture and literature, the role of A.S. Pushkin (1799-1837) is huge. Gogol expressed this beautifully: “With the name of Pushkin, the thought of a Russian national poet immediately dawns ... years". Pushkin's work is a natural result in the artistic interpretation of the life problems of Russia, from the reign of Peter the Great to his time. It was he who determined the subsequent development of Russian literature.

Pushkin's literary work clearly expresses the idea of the "universality" of Russian culture, and it is not just prophetically expressed, but is forever enclosed in his brilliant creations and his name has been proven. In the era of Pushkin, the golden age of Russian literature, art and, above all, literature acquired an unprecedented significance in Russia. Literature, in essence, turned out to be a universal form of social consciousness; it combined aesthetic ideas proper with tasks that were usually within the competence of other forms or spheres of culture. Such syncretism assumed an active life-creating role: in the post-Decembrist decades, literature very often modeled the psychology and behavior of the enlightened part of Russian society. People built their lives focusing on high book standards, embodying literary situations, types, ideals in their actions or experiences. Therefore, they put art above many other values.

This extraordinary role of Russian literature was explained in different ways at different times. Herzen attached decisive importance to the absence of political freedom in Russian society: "The influence of literature in such a society is acquiring dimensions that have long been lost by other European countries." Modern researchers (G. Gachev and others), without denying this reason, are inclined to suppose another, deeper one: for the holistic spiritual development of Russian life, internally "heterogeneous, which has absorbed several different social structures, it is not directly among themselves. connected, - it was precisely the form of artistic thinking that was required, and only this form is fully necessary for solving such a problem.

But whatever explains the increased interest of Russian society in art and its creators, especially in literature - this face of culture, this interest itself is obvious, here it is necessary to reckon with a well-prepared philosophical and aesthetic soil - the romantic philosophy of art, organically inherent in Russian culture of that era.

The horizons of Russian poets and writers of the Pushkin era included many ideas of French romantics: in Russia, the books by J. de Stael, F. Chateaubriand, articles-manifestos by V. Hugo, A. Vigny were well known; were known from memory the controversy associated with the judgments of J. Byron, but still the main attention was paid to the German romantic culture, provided by the names of Schelling, Schlegel, Novalis and their like-minded people. It is German romanticism that is the main source of philosophical and aesthetic ideas that entered the minds of Russian writers and, accordingly, were refracted in it.

If we look for the shortest formula of romanticism, then it will obviously be this: romanticism is the philosophy and art of freedom, moreover, unconditional freedom, unrestrained by anything. German romantics do not hesitate to reject the main thesis of the classicists and enlighteners, who consider the essence of art to be "imitation of Nature". Romantics are closer to Plato with his disbelief in the truth of the sensuously perceived world and with his teaching on the ascent of the soul to the supersensible, beyond the world. The same Novalis sometimes considers the creative personality as a kind of microcosm, in which all world processes are reflected, and the artist's imagination - as the ability to comprehend in revelation the true nature of the universe, the "divine universe". "A true poet is omniscient," exclaims Novalis, "he really is the universe in a small refraction." In general, German romantics created a myth about art, claiming to create the world by means of art.

The Russian philosophy of the art of the golden age of Russian literature does not accept the following three elements of German romanticism: its militant subjectivism, the unrestrained creative self-affirmation of genius declared by it, and the frequent exaltation of art over morality. Along with this, Russian writers subjected the ideas of German romantic philosophy of art to testing from different angles and with different results. Suffice it to recall the artistic experiments of V. Odoevsky, in which the aesthetic utopias of romanticism were subjected to various tests. As a result, the formula of "Russian skepticism" appeared - a paradoxical combination of criticism and enthusiasm. Since the check reveals a whole knot of contradictions and problems that are clearly insoluble within the framework of the current state of the world, it is precisely "Russian skepticism" that promotes the search for endlessly expanding horizons of thought. One of the results of this kind of search can be considered the movement of Russian artistic thought towards critical realism, a gravitation towards humanism.

The humanistic ideals of Russian society were reflected in its culture - in the highly civilian examples of architecture of that time and monumental decorative sculpture, in the synthesis with which decorative painting and applied art appear, but they appeared most vividly in the harmonious national style created by Pushkin, laconic and emotionally restrained, simple and noble, clear and precise. The bearer of this style was Pushkin himself, who made his life full of dramatic events a point of intersection of historical eras and modernity. Gloomy, tragic notes and joyful, bacchanal motives, taken separately, do not fully embrace the sourness of being and do not convey it. In them, the "eternal" is always associated with the temporary, transitory. The true content of being is in constant renewal, in the change of generations and eras, and again affirming the eternity and inexhaustibility of creation, which ultimately triumphs over the victory of life over death, light over darkness, truth over falsehood. In the course of this historical stream, simple, natural values will eventually be restored to their rights. This is the wise law of life.

The flowing darkness, the tragic chaos of reality, Pushkin opposed a bright mind, harmony and clarity of thought, completeness and integrity of sensations and perception of the world. Deep emotional movements are conveyed in his poetry naturally, with graceful artistry and genuine freedom, the form of lyrical expression is given an amazing lightness. It seems as if Pushkin writes jokingly, playing with any size, especially iambic. In this freely flowing poetic speech, the master's art gains genuine power over the subject, over the content, infinitely complex and far from harmonious. Here the mind forms the element of language, wins a victory over it, gives it order and, as it were, tangibly creates an artistic cosmos.

Pushkin's poetic style was created as a general norm, bringing all styles into harmonious unity and giving them wholeness. The stylistic synthesis he achieved opened the way for new poetic searches, internally already containing the styles of Fet, Nekrasov, Maykov, Bunin, Blok, Yesenin and other poets of the past and present centuries. And this applies not only to poetry. In Pushkin's prose - it was not for nothing that he was called "the beginning of all beginnings" -

Dostoevsky and Chekhov with their humanistic ideals of Russian culture.

Pushkin is at the center of all the creative searches and achievements of the poets of that time, everything seemed equally accessible to him, and it was not without reason that they compared him with Protem. N. Yazykov called Pushkin "the Prophet of the graceful", evaluating the artistic perfection of his creations, born in a controversial era. Pushkin's golden age of Russian literature was truly woven from creative contradictions. The sharp rise in the culture of verse itself, the power of Pushkin's voice did not suppress, but revealed the originality of the original poets. A faithful Karamzinist, combining dryish rationality and wit with unexpected negligence and ultimately triumphs over the victory of life over death, light over darkness, truth over falsehood. In the course of this unstoppable historical stream, simple, natural values will eventually be restored to their rights. This is the wise law of life with the emerging melancholic notes, P.A. Vyazemsky; fan of biblical literature and ancient virtues, deeply religious tyrant fighter F.N. Glinka; the most gifted of Zhukovsky's followers, a pacified and lyrical singer of grief and soul, I.I. Kozlov; a hardworking student of almost all poetry schools, redeeming with remarkable political audacity the original secondary nature of the author's manner, K.F. Ryleev; the singer of ancient hussar liberties, who inspired elegiac poetry with the fury of genuine passion, the poet-partisan D.V. Davydov; a concentrated master of the high poetic word, who rarely interrupts a long-term conversation with Homer, N.I. Gnedich - all these are poets who cannot be perceived otherwise than in the light of Pushkin's radiance.

"As for Pushkin," Gogol said, "he was for all poets, contemporary to him, like a poetic fire thrown from the sky, from which, like candles, other semi-precious poets were lit. A whole constellation of them formed around him ..." Together with Pushkin, such remarkable poets as Zhukovsky, Batyushkov, Delvig, Ryleev, Yazykov, Baratynsky and many others lived and worked, whose poems are evidence of the extraordinary flourishing and unique wealth of poetry at the beginning of the 19th century. The poets of this time are often spoken of as the poets of the "Pushkin galaxy" who have "a special imprint that favorably distinguishes them from the poets of the next generation" (IN Rozanov). What is this special imprint?

First of all, it is in the sense of time, in the desire to affirm new ideas, new forms in poetry. The very ideal of the beautiful also changed: the unlimited domination of reason, the abstract normativity of the aesthetics of classicism was contrasted with feeling, the emotional and spiritual world of man. The requirement for the subordination of the individual to the state, abstract duty was replaced by the affirmation of the personality itself, an interest in the feelings and experiences of a private person.

Finally, and this is also extremely important, the poets of the Pushkin era are united by the cult of artistic skill, harmonious perfection of form, completeness and grace of verse - what Pushkin called "an extraordinary sense of the graceful." A sense of proportion, impeccability of artistic taste, artistry are the qualities that distinguished the poetry of Pushkin and his contemporaries. In the "Pushkin Pleiad" there were not just satellites that shone with the reflected light of Pushkin's genius, but the stars of the first magnitude, who followed their own special paths, which is embodied in the trends in the development of poetry of the Pushkin era.

The line of romantic, subjective-emotional, psychological lyrics is presented primarily by Zhukovsky and Kozlov, who follows him. It ends with the philosophical lyrics of Venevitinov and the "wisdom" poets. On a different basis, this tradition is reflected in the lyrics of Baratynsky.

Another trend, although influenced by romantic aesthetics, is a kind of neoclassicism, which arose from the appeal to antiquity, the continuation of the best achievements of classicism. Gnedich, Batyushkov, Delvig generously paid tribute to antiquity and at the same time cultivated elegiac poetry characteristic of romanticism. Teplyakov adjoins them with his "Thracian Elegies".

The third group - the poets of the civil direction, primarily the Decembrist poets, who combined in their work the educational, odic traditions of the 18th century with romanticism. Ryleev, Glinka, Kuchelbecker, Katenin, early Yazykov and A. Odoevsky represent this civic line in poetry.

And finally, the last trend is poets who to a large extent shared the positions of civic poetry and romanticism, but already turned to a sober, realistic depiction of reality. These are, first of all, Pushkin himself, as well as Denis Davydov, Vyazemsky, Baratynsky, whose realistic tendencies of creativity are manifested in very different ways.

It is clear that typological schemes of this kind take into account, first of all, the common features of poets of different schools. No less essential is the poet's individuality, uniqueness, his "face is not a common expression," as Baratynsky said. In his - "Reflections and analyzes" P. Katenin, putting forward the requirement to create his own national "folk" poetry and not agreeing with its division into different directions, wrote: "For a connoisseur, beauty in all forms and is always beautiful ..." Russian literature is the poetry of Pushkin, which is why Russian thinkers are discussing the three secrets of the genius of Russian classics.

The first, which has long amazed everyone, is the mystery of creativity, its inexhaustibility and completeness, in which all the previous ones are united and all the subsequent development of Russian literature is enclosed. At the same time, Pushkin turned out to be not just a predecessor, but what an amazing finalizer of the tendencies emanating from him, which is more and more revealed in the course of the literary-historical process. The harmony and perfection of Pushkin's spirit, sometimes defined as the divine spirit, are amazing (V. Rozanov insists on this).

Russian philosophers (V. Ilyin, P. Struve, S. Frank and others) see the secret of the spirit in Pushkin's genius. That catharsis, that harmonious beauty, into which everything unhappy and tragic in a person's life is resolved, is interpreted by Russian philosophers as the work of not only poetic] gift, but also human "self-restraint" (P. Struve), "self-overcoming", "self-control "(S. Frank), sacrifice, asceticism. Pushkin's work is an act of self-sacrifice.

At the same time, it turns out that Pushkin consoles us not with the ghostly consolation of a stoic, which is often attributed to him in literature, but with such a sage's benevolence for the whole universe, through which conviction in its meaning is revealed to us. Thus, the mystery of creativity also leads to the mystery of Pushkin's personality - and this is the main thing that attracts the attention of Russian thinkers. They ponder the riddle of the passionate attraction of the Russian soul to every sign that emanates from him. "Pushkin is a wonderful secret for the Russian heart" (A. Kartashev); and it consists in the fact that he is the personal embodiment of Russia, or, according to S. Bulgakov, "the revelation of the Russian people and the Russian genius." But in this regard, it is necessary to understand the phenomenon of "Russianness", which is becoming especially relevant in our time.