Archaic time. Archaic period of ancient greece

The Archaic period in the history of Ancient Greece (750-480 BC) occupies a special place. At this time, the foundations of culture and development of society were laid, which were continuously improved over the next centuries. Greece of the archaic period is the improvement of crafts and shipbuilding, the emergence of real money and the widespread use of iron. There is debate about the time frame of the archaic period. It is customary to consider it within the 8-5 centuries BC.

Economy and society of the archaic period

The changes in all areas were driven by the economic recovery. The use of iron made it possible to develop viticulture and increase the amount of olive production. As a result, the surplus began to be exported outside Greece, and agriculture stimulated profit-making. Ties were strengthened between the policies, economic transformations significantly changed Greece. As a natural result - the emergence of money, and the amount of land is no longer an indicator of wealth. In all Greek policies, the number of artisans, traders, workshop owners increased, peasants sold their products at popular meetings - the cities of Greece began to form a culturally, politically and economically full-fledged society.

The pace of the economy grew rapidly, and the stratification in society grew just as rapidly. Social groups and classes appeared in the Greek city-states. Somewhere such processes proceeded more intensively, somewhere more slowly - for example, in areas where agriculture was of greater importance. The very first class of merchants and artisans emerged. This stratum gave rise to "tyranny" - coming to power with the use of force. But among the tyrants there were many who in every possible way supported the development of trade, crafts, and shipbuilding. And only then did real despots appear, and the phenomenon took on a negative connotation.

A special stage of the archaic period is the Great Greek colonization. Poor people, not resigned to stratification, were looking for a better life in the new Greek colonies. This state of affairs was beneficial to the rulers: it was easier to extend influence to new lands. The most widespread was the colonization of the southern direction: the east of Spain, Sicily, part of Italy, Corsica and Sardinia. North Africa and Phenicia were inhabited in the southeast, and the shores of the Black and Marmara Seas in the northeast. The event that subsequently influenced the course of history was the founding of Byzantium - the city-progenitor of the great Constantinople. But its development and growth already belong to other, subsequent eras.

The result of the socio-political development of the archaic period was the birth of the classic polis - a small city-state: several villages around one urban center with a total area of 100-200 square meters on average and with a population of 5-10 thousand people. (of which citizens are 1–2 thousand). The city was a place of socially significant events - religious rites and festivals, popular gatherings, theatrical performances, sports competitions. The center of the city's life was the central city square (agora) and temples. The spiritual basis of the polis was a special polis worldview (the ideal of a socially active free citizen, patriot and defender of the fatherland; subordination of personal interests to public interests). The small framework of the city-state allowed the Greek to feel his close connection with him and his responsibility for him (direct democracy).

Archaic culture

Detailed article -

Pottery and vase painting... During the Archaic period, the earliest forms of ancient Greek art developed - sculpture and vase painting, which in the later classical period became more realistic.

In the vase painting in the middle and 3rd quarter of the 6th century. BC NS. the black-figure style reached its peak and around 530 BC. NS. - red-figure style.

In ceramics, the orientalizing style, in which the influence of the art of Phenicia and Syria is noticeable, supplants the previous geometric style.

The late Archaic period is associated with such vase painting styles as black-figure ceramics, which arose in Corinth in the 7th century. BC e., and later red-figure pottery, which was created by the vase painter Andocides around 530 BC. NS.

In ceramics, elements are gradually emerging that are not typical for the archaic style and are borrowed from Ancient Egypt - such as the "left foot forward" pose, "archaic smile", a stereotyped stylized image of hair - the so-called "helmet-hair".

Architecture. Archaic - the time of addition of monumental figurative and architectural forms. In the Archaic era, Doric and Ionic architectural orders were formed.

Sculpture. The main types of monumental sculpture are being formed - statues of a naked young athlete (kouros) and a draped girl (bark).

The sculptures are made from limestone and marble, terracotta, bronze, wood and rare metals. These sculptures, both freestanding and reliefs, were used to decorate temples and as tombstones. The sculptures depict both stories from mythology and everyday life. Life-size statues suddenly appear around 650 BC. NS.

The archaic period was the period of the creation of the Greek slave society and state and the addition of many important aspects of Greek culture and art. It was a period of rapid development of society, a period of growth of its material and spiritual wealth.

The complexity and contradictions of the art of the archaic period were explained by the transitional nature of this historical stage in the development of Greek society.

The power of the head of the tribe, Basileus, back in the 8th century. BC. was strongly limited by the domination of the clan aristocracy - the Eupatrides, who concentrated wealth, land, slaves in their hands - and then, in the 7th century. BC, disappeared altogether. The decomposition of the old primitive communal relations, property inequality, as well as the increasingly widespread use of slave labor, led to the formation of the slave system in Greece. The development of trade and crafts caused the flourishing of urban life and temporary growth along with slave and free labor, and with it - the demos, that is, the masses of free citizens of the polis, opposing the old clan aristocracy.

The archaic period became a time of fierce class struggle between the old clan nobility - the Eupatrides and the people - demos, that is, the mass of free members of the community.

It was during the archaic period that system of architectural orders, which formed the basis for all further development of ancient architecture. At the same time, narrative plot vase painting flourishes and the path is gradually outlined to depicting a beautiful, harmoniously developed person in sculpture.

In the architecture of the archaic, the progressive trends of the art of this time were manifested with the greatest force. Already in ancient times, the art of Greece created a new type of building, which in the course of the centuries became a vivid reflection of the ideas of the demos, that is, the free citizens of the city-state.

Such a building was a Greek temple, the fundamental difference of which from the temples of the Ancient East was that it was the center of the most important events in the public life of the citizens of the city-state. The temple was the repository of the public treasury and artistic treasures, the square in front of it was a place of meetings and festivities. The temple embodied the idea of unity, greatness and perfection of the city-state, the inviolability of its social order.

The simplest and oldest type of stone archaic temple was the so-called "Temple in antah"... It consisted of one small room - naosa open to the east. On its facade, between the antes, that is, the protrusions of the side walls, two columns were placed.

The more perfect type of temple was prostyle, on the front facade of which four columns were placed. IN amphiprostyle the colonnade adorned both the front and rear façades, where the entrance to the treasury was.

The classic type of Greek temple was peripter, that is, a rectangular temple surrounded on all four sides by a colonnade. The peripter in its main features took shape already in the second half of the 7th century. BC..

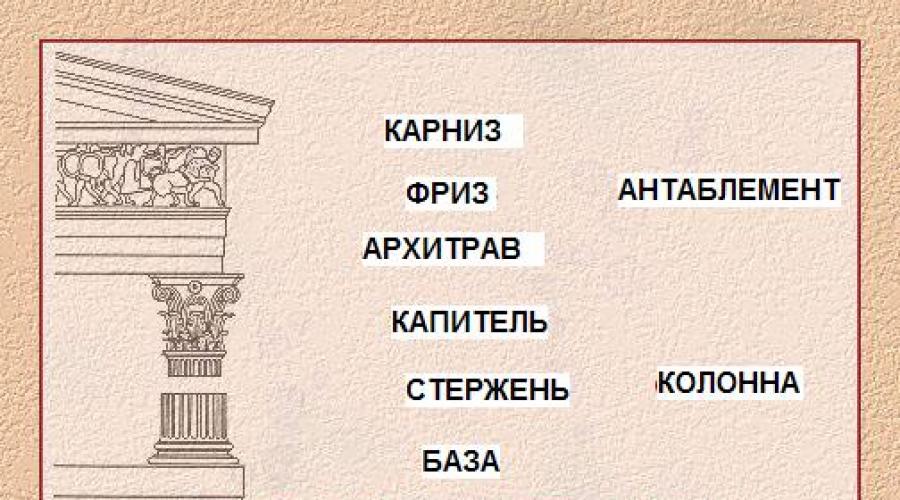

The main structural elements of the peripter are very simple and deeply popular in origin. In its origins, the construction of a Greek temple dates back to wooden architecture with adobe walls. From here there is a gable roof and (subsequently, stone) beamed ceilings; the columns also go back to the wooden posts. As a result of the processing and development of the traditions of antiquity, a clear and integral artistically meaningful architectural system was formed, which later, among the Romans, was called warrants(which means order, order). As applied to Greek architecture, the word order implies in a broad sense the entire figurative and constructive structure of Greek architecture, mainly the temple, but more often it means only the order of the ratio and arrangement of the columns and the one lying on them entablature(overlap).

The aesthetic expressiveness of the order system was based on the appropriate harmony of the ratio of the parts that form a single whole, and on the feeling of an elastic, lively balance of the bearing and being carried parts. Even very insignificant changes in the proportions and scales of the order made it possible to freely modify the entire artistic structure of the building.

In the archaic era, the Greek order took shape in two versions - Doric and ionic... This corresponded to the two main local schools of art.

The Doric order, according to the Greeks, embodied the idea of masculinity, that is, the harmony of strength and solemn severity. The Ionian order, on the contrary, was light, slender and well-dressed; when in the Ionic order the columns were replaced by caryatids, it was not by chance that graceful and elegant female figures were placed.

The column was the most important part of the order, since it was the main bearing part. The Doric column relied directly on stylobate; its proportions in the archaic period were usually squat and powerful (height equal to 4-6 lower diameters). The Doric column consisted of a trunk ending at the top with a capital. The trunk was cut through a series of longitudinal grooves - flute... Doric columns were not geometrically precise cylinders. In addition to the general narrowing upwards, at a height of one third, they had a certain uniform thickening - entasis, which was clearly visible on the silhouette of the column. Entasis, like the tense muscles of a living creature, created the feeling of an elastic force with which the columns carried entablature. The Doric capital was very simple; it consisted of echina- a round stone pillow, - and abacus- a low stone slab, on which the pressure of the entablature lay.

The entablature consisted of architrave, that is, a beam that lay directly on the columns and carried the entire weight of the floor, frieze and cornice. The Doric architrave was smooth. The Doric frieze consisted of triglyphs and metope... The triglyphs were divided into three stripes by vertical grooves. The metopes were rectangular tiles. The cornice completed the entablature.

The triangles formed on the front and rear, facades - under a gable roof - were called gables... The ridge of the roof and its corners were crowned with sculptural (usually ceramic) decorations, the so-called acrotheria... The pediments and metopes were filled with sculpture.

The capital of the Ionic order had an echinus, forming two graceful curls - volutes... Later, already in the era of the classics, the third order was developed - Corinthian. In it, the columns, more elongated in proportion (the height of the column reaches 12 lower diameters), were crowned with a lush and complex basket-shaped capital, composed of floral ornament - stylized acanthus leaves - and curls (volut).

In archaic architecture, built of limestone, bright colors were widely used. The main one was most often a combination of red and blue colors.

The archaic period was the heyday of artistic crafts. The need for products of applied art was caused by the growth of the well-being of a significant part of the free population and the development of overseas trade. Greek ceramics reached a particularly high flowering.

Greek vases served a wide variety of purposes and needs. They were very varied in shape and size. Usually the vases were covered with artistic painting. During the early archaic period (7th century BC), the so-called "orientalizing" (that is, imitating the East) style prevailed in Greek vase painting. The artists of these vases combined in one composition schematic images of humans, animals or fantastic creatures with purely ornamental motives, trying to fill the entire field of the composition, leaving no empty spaces, and thus create the impression of a decorative whole. In the 6th century. BC. the orientalizing style was replaced by the so-called black-figure vase painting. The patterned ornament was replaced by a clear silhouette pattern that characterizes the general appearance of the figure and more or less expressively conveys gesture and movement. Drawings of people and animals were filled with black varnish and stood out clearly against the reddish background of baked clay

Black-figure vase painting reached its greatest flourishing in Attica.

The largest Attic vase painter of the middle of the 6th century. BC. (550 - 530), with the greatest power to reveal all the living and progressive sides of black-figure vase painting, was Exekius.

For example, a drawing on an amphora depicting Ajax and Achilles playing dice. The image of Dionysus in a boat (painting of the bottom of the cilicus), characterized by a delicate sense of rhythm and mastery of composition, also gives an idea of the high skill of Exekius.

With the further growth of realism in Greek art in vase painting, there was a tendency to overcome the flatness and conventionality inherent in the entire artistic system of black-figure vase painting. This resulted in about 530 BC. to a whole revolution in the technique of vase painting - to the transition to the so-called red-figure vase painting with light figures on a black background.

In sculpture almost until the very end of the Archaic period - until the middle of the 6th century. BC. strictly frontal and motionless statues of the gods were created, as if frozen in solemn peace. These statues corresponded to ancient traditions, a canonical scheme that does not allow artists to violate the rules for making this kind of sculpture. This type of statues includes "Artemis" from the island of Delos, "Hera" from the island of Samos, "Goddess with a pomegranate apple" of the Berlin Museum. "Artemis" from the island of Delos (7th century BC) is an almost undivided stone block with poorly outlined body shapes. The head is erect, the hair falls symmetrically on the shoulders, the arms are lowered along the body, the feet seem to be mechanically attached to a lumpy mass of long clothes.

Particularly typical of the archaic period were erect nude statues of heroes, or, later, warriors, the so-called kuros.

The kouros type developed during the 7th and early 6th centuries. BC .. His appearance was of great progressive importance for the further development of Greek sculpture. The very image of a kouros - a strong, courageous hero or warrior - was associated with the development of a person's civil consciousness; it meant a big step forward from the old artistic ideals. Associated first with the cult of heroes, these statues of the Kuros by the 6th century. BC. they began to associate with even more vital images of ideal warriors - they began to serve as tombstones for warriors and are erected in honor of the winners of Olympic and other competitions. From the second half of the 6th century. BC. in archaic sculpture (including relief), realistic quests began to emerge more clearly and distinctly. The most advanced of the late Archaic Greek art schools was the Attic school. Athens, the main city of Attica, already in the late archaic period acquired the significance of the largest artistic center, where masters flocked from all over Greece.

One of the highest achievements of the archaic art of Athens at the end of the 6th century. BC. were found on the Acropolis beautiful statues of girls (kor) in smart clothes. bronze statue of a young man, made around 500 BC, - the so-called "Apollo of Piombino",

Archaic period: 7th - 6th centuries BC.

The period of big shifts in the economy is the emergence of money. The social system is the formation of a Greek slave-owning society and a state - a slave-owning republic (in power, not a sole ruler, as in the East, but - an aristocratic elite). Where the demos (farmers, artisans, merchants) triumphed, a democratic republic was established.The country is divided into regions or city-states - policies. But there is no struggle because of trade ties and military clashes with other peoples, slaves of foreigners. Between the poleis, there is a consciousness of the unity of the Greek world.

The sanctuaries are of general Greek importance, especially the temple of Zeus at Olympia, where from 776 BC. Olympic Games are held.

Architecture

In the 7th century. cities are growing rapidly and construction is expanding. Monumental limestone buildings appear. Basically, these are temples, which were not only religious, but also public buildings.In the 7th century. various types of buildings are produced:

The simplest one is the temple in antae (takes roots in the Mycenaean megaron). Columns between the ends of the side walls - antas.

Prostyle - 4 columns on the facade, located in front of the ants.

Amphiprostyle - columns on the front and back facades.

Peripter - columns along the entire perimeter of the temple. Most often, there are 6 columns on the facade (hexastyle peripter). The most common type of temple.

Dipter - two rows of columns surround the temple.

The premise of the temple (cella) is divided into 3 parts:

- front - pronaos - serves as a vestibule;

- central - naos, the most extensive;

- an opisthode - for storing houses, with an entrance from the rear facade.

Elements of the order system:

- basement part, three-stage (stylobate);

- column (base, trunk, capital);

- entablature (consisting of an architrave (beam), frieze and cornice) - the overlapping part of the structure.

- a triangular pediment formed by two roof slopes.

There were 2 main orders - Doric (simplicity and masculinity of forms) and Ionic (lightness, harmony, grace, relatively large decorativeness).

In the Doric order, the columns had no bases.

The greatest flowering of the classics of the 5th - 4th centuries. would not have been possible without the great achievements of the archaic period.

Throughout Greece, many temples are being built, especially in the 6th century. Everywhere they are moving to the construction of temples from stone.

Temples were decorated with sculptures (pediment, frieze, metopes).

The most difficult task is to place the multi-figured composition in the triangular field of the pediment.

An unusually wide main façade. The shape of the columns is peculiar - the upper diameter is much narrower than the lower one, bulky capitals have a large extension.

An odd number of columns, the main room divided by a row of columns into two parts (nave) are typically archaic features.

Not one of the monuments of the Ionic order has reached us in such a state that it could be viewed in its entirety.

The transition from the archaic to the classics (late 6th - early 5th century)

Temple of Hera (II) at Paestum. The columns are still heavy, but the shape is closer to the classical one.

art

The fine arts (7th - 6th centuries) of the archaic laid the foundation for the future flourishing of classical art, which played such a significant role in the development of world artistic culture.During this period, all types of art develop rapidly.

The search for a form that expresses the ideal of a beautiful, strong, healthy in body and spirit citizen of the polis. Creative efforts are aimed at mastering the correct construction of the figure, plastic anatomy, transmission of movement. The latter is the most difficult. The complete illusion of movement will be only in the middle. 5 c.

The lawsuit had a great influence - in Egypt and Mesopotamia. For example, from the more perfect Assyrian, they borrowed the composition, interpretation of clothes and hairstyles.

The appearance of a nude athletic figure - kuros (male) and bark (female). Both people and gods were depicted.

Kuros of the Shadow. T.N. Apollo of the Shadow. Marble. 560 BC The athletic build is accentuated by broad shoulders and powerful legs. Softer and more voluminous than previously transferred musculature. But the hairstyle is treated decoratively, strongly protruding eyes, a conditional smile.

Even more voluminous and realistic.

Work on the draped figure and attempts to convey movement:

Female statue (goddess with a hare). 560 BC Presumably the iconic statue of Hera. While static, the lower part is in the form of a round pillar. The folds of the chiton are strictly parallel, although the arms and chest are already plastically modeled.

A group of female statues of the 2nd floor is distinguished by a special skill. 6 c.

Peplos bark from the Acropolis of Athens. Marble coloring book. 540 BC

Bark from the Acropolis. Detail. Attempts to match the folds of clothing with body movement. Marble. Excellently crafted. Beautifully painted. Graceful poses - the image of girls of the aristocratic circle.

Temple sculpture (metopes, pediments, zophoric friezes).

Mostly mythological plots.

Metopes from the temple in Paestum speak of the search for new compositional constructions.

Athena and Perseus killing the Gorgon. A metope from ridge. in Selinunte. 2nd floor 6 c. BC. layout in a square.

The most difficult task is the arrangement of the pediment in the field.

Pediment of the Temple of Artemis from the island of Kerkyra. Gorgon. Detail. Fragment. 6 c. BC NS. A bold attempt to convey flight - a conventional kneeling posture. Quite flat, poorly modeled terrain.

Painting

Expansion of subject matter, more realistic drawing, different angles of figures, movement, polychromy - these are the achievements of the time of the archaic (7th - 6th centuries).The silhouette is replaced with an outline drawing to convey details.

In the 6th century. black-figure technique dominates.

the illustrious François Crater. The vase painter Cletius, the potter Ergotim. OK. 570 (named after the archaeologist). 5 belts, mythological scenes, signatures about what is happening. Thoroughness of drawing, variety of movements. The most important masters are Amasis and Exekios. One of the best works of Exekia:

Archaic period

The term means an early stage in the development of civilization. For example, in Egypt, the A. n. Encompasses the first two dynasties (3200–2800 BC), during which the country was united and its culture first flourished. In Greece, A. n. Corresponds to the formation of civilization (from 750 BC to the Persian invasion of 480 BC). In the understanding of Americanists, the term means not so much a chronological period as a stage in development. It is characterized by hunting and gathering as the backbone of the economy in the post-Pleistocene environment. Under certain circumstances, tribes can move to a sedentary lifestyle, pottery making and even agriculture, but in addition to collecting wild plants. The term was developed for certain cultures of the forest belt of eastern North America (dating from 8000–1000 BC), but soon it was used (often uncritically) for any other cultures that showed a similar level of development without regard to their dating.

Archaeological Dictionary. - M .: Progress. Warwick Bray, David Trump. Translated from English by G.A. Nikolaev. 1990 .

See what the "Archaic period" is in other dictionaries:

Archaic Southwest- Archaic southwest, eng. The Archaic Southwest is a term encompassing the archaeological cultures of the US Southwest between roughly 6500 BC. NS. and 200 AD NS. The cultures belonging to the specified period were ... Wikipedia

Hellenic period- History of Greece Prehistoric Greece (up to XXX century BC) Aegean civilization (XXX XII BC) Western Anatolian civilization Minoan civilization ... Wikipedia

Pre-dynastic period (Ancient Egypt)- History of Ancient Egypt Pre-dynastic period 00 ... Wikipedia

Woodland period- Woodland period, eng. The Woodland period in the pre-Columbian chronology of North America dates back to about 1000 BC. NS. to 1000 AD NS. in the eastern part of North America. The term "Woodland" ... ... Wikipedia

Tribes of the Caucasus during the Eneolithic period- The largest copper production center was located on the border of Asia and Europe in the Caucasus. This center was especially important because the Caucasus was directly connected with the advanced countries of the then world with the slave-owning states ... ... The World History. Encyclopedia

Archaic Greece

Ancient Greece- History of Greece Prehistoric Greece (up to XXX century BC) ... Wikipedia

History of Uzbekistan- History of Uzbekistan ... Wikipedia

Ancient Greek Art- "Delphic charioteer", approx. 475 BC e., Archaeological Museum, Delphi. One of the few surviving originals of antique bronze ... Wikipedia

Ancient greek literature- This article should be wikified. Please, arrange it according to the rules of article formatting ... Wikipedia

Books

- Archaic thinking. Yesterday, today, tomorrow, P.P. Fedorov, As a result of ethnographic research in the twentieth century, the question of a special archaic thinking was raised: a savage is no more stupid than a civilized person, but thinks differently (in the first ... Category: Anthropology Publisher: URSS, Manufacturer: URSS, Buy for 735 UAH (only Ukraine)

- Early Greek Tyranny Reader, S. Zhestokanov (comp.), Compiled by S.M. Zhestokanov, Associate Professor of St. Petersburg State University, this anthology is devoted to one of the most interesting and controversial phenomena in the history of ancient Greece - early Greek tyranny (VII - 1st half. ... Category:

The so-called archaic period, covering the VIII-VI centuries. BC e., is the beginning of a new important stage in the history of ancient Greece. During these three centuries, i.e., in a relatively short historical period, Greece far outstripped neighboring countries in its development, including the countries of the ancient East, which until that time were at the forefront of the cultural progress of mankind.

The Archaic period was the time of the awakening of the spiritual forces of the Greek people after almost four centuries of stagnation. This is evidenced by an unprecedented explosion of creative activity.

Once again, after a long break, seemingly forgotten forms of art are reviving: architecture, monumental sculpture, painting. The colonnades of the first Greek temples are erected from marble and limestone. The statues are carved out of stone and cast in bronze. The poems of Homer and Hesiod, the lyrical verses of Archilochus and Saffo, surprising in depth and sincerity of feeling, appear. Alkea and many other poets. The first philosophers are Thales. Anaximenes. Anaximander - intensely reflecting on the question of the origin of the universe and the fundamental principle of all things.

The rapid growth of Greek culture during the 8th - 6th centuries. BC NS. was directly associated with the Great Colonization taking place at that time. Earlier (see “Early Antiquity,” lecture 17) it was shown that colonization brought the Greek world out of the state of isolation it found itself in after the collapse of the Mycenaean culture. The Greeks learned a lot from their neighbors, especially from the peoples of the East. So, the Phoenicians borrowed the alphabetic writing, which the Greeks improved by introducing the designation not only of consonants, but also of vowels; the modern alphabets, including Russian, originate from here. From Phenicia or from Syria to Greece came the secret of making glass from sand, as well as the method of extracting purple paint from the shells of sea mollusks. The Egyptians and Babylonians became teachers of the Greeks in astronomy and geometry. Egyptian architecture and monumental sculpture strongly influenced the nascent Greek art. From the Lydians, the Greeks adopted such an important invention as coinage.

All these elements of foreign cultures were creatively reworked, adapted to the urgent needs of life and entered as organic components in Greek culture.

Colonization made Greek society more mobile, more receptive. It opened up a wide scope for the personal initiative and creative abilities of each person, which contributed to the release of the individual from the control of the clan and accelerated the transition of the whole society to a high level of economic and cultural development. In the life of Greek city-states, navigation and maritime trade now come to the fore. Initially, many of the colonies on the remote periphery of the Hellenic world became economically dependent on their metropolises.

The colonists were in dire need of basic necessities. They lacked such foods as wine and olive oil, without which the Greeks could not imagine a normal human life at all. Both had to be delivered from Greece by ship. Pottery and other household utensils were also exported from the metropolises to the colonies, then textiles, weapons, jewelry, etc. These things attract the attention of local residents, and they offer in exchange for them grain and cattle, metals and slaves. The unpretentious products of Greek artisans initially could not, of course, compete with the high-quality oriental goods that Phoenician merchants transported throughout the Mediterranean. Nevertheless, they were in great demand in the markets of the Black Sea, Thrace, and the Adriatic, remote from the main sea routes, where Phoenician ships appeared relatively rarely. In the future, cheaper, but more massive products of Greek handicraft began to penetrate into the "reserved zone" of the Phoenician trade - to Sicily.

Southern and Central Italy, even Syria and Egypt - and gradually conquers these countries. Colonies are gradually turning into important centers of intermediary trade between the countries of the ancient world. In Greece itself, the main centers of economic activity are the policies, which are at the head of the colonization movement. Among them are the island cities of Euboea, Corinth and Megara in the Northern Peloponnese, Aegina, Samos and Rhodes in the Aegean archipelago, Miletus and Ephesus on the western coast of Asia Minor.

The opening of markets on the colonial periphery gave a powerful impetus to the improvement of handicraft and agricultural production in Greece itself. Greek artisans persistently improve the technical equipment of their workshops. In the entire subsequent history of the ancient world, never again were so many discoveries and inventions made as in the three centuries that made up the archaic period. Suffice it to point out such important innovations as the discovery of a method for brazing iron or bronze casting. Greek vases of the 7th-6th centuries BC NS. amaze with the richness and variety of forms, the beauty of the picturesque design. Among them are the vessels of the work of Corinthian masters, painted in the so-called orientalizing, that is, "oriental" style (it is distinguished by the colorfulness and fantastic whimsy of the pictorial decor, reminiscent of drawings on oriental carpets), and later black-figure style vases, mainly Athenian and Peloponnesian production. The products of Greek ceramists and bronze castors testify to high professionalism and a far advanced division of labor not only between industries, but also within individual branches of handicraft production. The bulk of the ceramics exported from Greece to foreign markets was made in special workshops by skilled potters and vase painters. Specialists-artisans were no longer, as once, powerless loners who stood outside the community and its laws and often did not even have a permanent place of residence. Now they form a very numerous and rather influential social stratum. This is indicated not only by the quantitative and qualitative growth of handicraft products, but also by the appearance in the most economically developed policies of special craft quarters, where artisans of one particular profession settled. So, in Corinth, starting from the 7th century. BC NS. there was a quarter of potters - Ceramics. In Athens, a similar quarter, which occupied a significant part of the old city, arose in the 6th century. BC NS. All these facts indicate that during the archaic period in Greece there was a historical shift of great importance: handicrafts finally separated from agriculture as a special, completely independent branch of commodity production. Accordingly, agriculture is also being restructured, which can now focus not only on the internal needs of the family community, but also on market demand. Communication with the market becomes a matter of paramount importance. Many Greek peasants at that time had boats or even whole ships on which they delivered the products of their farms to the markets of nearby cities (land roads in mountainous Greece were extremely inconvenient and unsafe due to robbers). In some areas of Greece, peasants are moving from growing poorly successful grain crops to more profitable perennial crops - grapes and oilseeds: excellent Greek wines and olive oil were in great demand in foreign markets in the colonies. In the end, many Greek states abandoned the production of their own grain altogether and began to live off the cheaper imported grain.

So, the main result of the Great Colonization was the transition of Greek society from the stage of primitive subsistence economy to a higher stage of commodity-money economy, which required a universal equivalent of commodity transactions. In the Greek cities of Asia Minor, and then in the most significant policies of European Greece, their own monetary standards appeared, imitating the Lydian. Even before that, in many regions of Greece, small metal (sometimes copper, sometimes iron) bars were used as the main exchange unit, called obolami (literally, "knitting needles", "skewers"). Six obols made up a drachma (literally, "a handful"), since so many of them could be grasped with one hand. Now these ancient names were transferred to new monetary units, which also began to be called obols and drachmas. Already in the VII century. in Greece, two main coinage standards were in use - the Aeginian and Euboean. The Euboean standard was adopted, in addition to the island of Euboea, also in Corinth, Athens (from the beginning of the 6th century) and in many Western Greek colonies, in other places they used the Aegian standard. Both systems of coinage were based on a weight unit called talent (Tal ant as a weight unit was borrowed from Asia Minor; Babylonian talent (biltu, about 30 kg) of 60 minutes, or 360 shekels, and Phoenician talent (kikkar , about 26 kg, which is equal to the Euboean talent) of 60 minutes, or 360 shekels. The Aegipan talent weighed 37 kg. - Ed. note), which in both cases was divided into 6000 drachmas (drachmas were usually minted from silver, obol - from copper or bronze). "Money makes a person" - this dictum, attributed to a certain Spartan Aristodemus, has become a kind of motto of the new era. Money has accelerated many times over the process of property stratification of the community, which had begun even before its appearance, and brought the complete and final triumph of private property even closer.

Purchase and sale transactions now apply to all types of material assets. Not only movable property: livestock, clothing, utensils, etc., but also land, which until now was considered the property not of individuals; but of the clan or the entire community, freely pass from hand to hand: sold, pledged, passed on by will or as a dowry. The already mentioned Hesiod advises his reader to seek the favor of the gods with regular sacrifices, "so that," he finishes his instruction, "you buy the plots of others, and not yours — others."

Money itself is bought and sold. A rich man could lend them to a poor man at an interest rate that, according to our concepts, is very high (18% per annum in those days was not considered too high a norm) (As we saw above, in ancient Western Asia of the previous period, the interest rate was much higher. an increase in the marketability of farms and, consequently, a certain decrease in their dependence on usurious credit, the domination of which in Greece turned out to be short-lived.- Ed. note). Debt slavery appeared along with usury. Self-mortgage transactions are becoming commonplace. Unable to timely pay off his creditor, the debtor pledges his children, his wife, and then himself. If the debt and the interest accumulated on it were not paid after that, the debtor with his entire family and the remnants of property fell into bondage to the usurer and turned into a slave whose position was no different from that of slaves taken prisoner or bought on the market. Debt slavery was a terrible danger for the young and still not strong Greek states. It depleted the internal forces of the polis community, undermined its combat capability in the fight against external enemies. In many states, special laws were passed that prohibited or limited the enslavement of citizens. An example is the famous Solonovskaya seisakhteya (“shaking off the burden”) in Athens (see about it below). However, purely legislative measures would hardly have been able to eradicate this terrible social evil if the slaves of fellow tribesmen had not been replaced by foreign slaves.The spread of this new and, for that time, undoubtedly more progressive form of slavery was directly associated with colonization. In those days, the Greeks had not yet fought big wars with neighboring peoples. The bulk of the slaves entered the Greek markets from the colonies, where they could be purchased in large quantities and at affordable prices from the local kings. Slaves constituted one of the main articles of Scythian and Thracian exports to Greece; they were exported in masses from Asia Minor, Italy, Sicily and other areas of the colonial periphery.

The surplus of cheap labor in the markets of Greek cities made possible for the first time the widespread use of slave labor in all major branches of production. Purchased slaves now appear not only in the homes of the nobility, but also in the farms of wealthy peasants.

Slaves could be seen in craft workshops and merchant shops, in markets, in the port, in the construction of fortifications and temples, in mining. Everywhere they performed the most difficult and humiliating work that did not require special training. Thanks to this, their owners, the citizens of the polis, created an excess of free time, which they could devote to politics, sports, art, philosophy, etc. This is how the foundations of a new slave-owning society were laid in Greece and at the same time a new polis civilization, sharply different from the previous one. her palace civilization of the Cretan-Mycenaean era. The first and most important sign of the transition of Greek society from barbarism to civilization was the formation of cities. It was precisely in the archaic era that the city for the first time truly separated from the village both politically and economically subordinated it to itself. This event was associated with the separation of handicrafts from agriculture and the development of commodity-child relations (However, the Greeks themselves saw the main feature of the city not from trade and industrial activities, but in the political independence of the settlement, its independence from other communities. ) could also be considered unfortified settlements that had independence for reasons of a military-political nature.).

Almost all Greek cities, with the exception of the colonies, grew out of the fortified settlements of the Homeric era - polis, retaining this ancient name. Between the Homeric polis and the archaic polis that replaced it, there was, however, one very significant difference. Homer's policy was at the same time both a city and a village, since there were no other settlements competing with it on the territory under its control. The archaic polis, on the contrary, was the capital of a dwarf state, which, in addition to itself, also included villages (in Greek, comas), located on the outskirts of the territory of the polis and politically dependent on it.

It should also be borne in mind that in comparison with Homeric time, the Greek city-states of the Archaic period became larger. This enlargement took place both due to natural population growth and due to the artificial merger of several villages of the village type into one new city. To this measure, called synekism in Greek, i.e. "Joint settlement", resorted to many communities in order to strengthen their defenses in the face of hostile neighbors. There were no big cities in the modern sense of the word in Greece yet. Polis with a population of several thousand people were an exception: in most cities the number of inhabitants did not exceed, apparently, a thousand people. An example of an archaic polis is ancient Smyrna, excavated by archaeologists; part of it was on the peninsula, which closed the entrance to a deep bay - a convenient ship dock. The center of the city was surrounded by a brick defensive wall on a stone dock. There were several gates in the wall with towers and observation decks. The city had the correct layout: the rows of houses were strictly parallel to each other. There were several churches in the city. The houses were quite spacious and comfortable, some of them even had terracotta baths.

The main life center of the early Greek city was the so-called agora, which served as a place for popular gatherings of citizens and at the same time was used as a market square. The free Greek spent most of his time here. Here he bought and sold, here in the community of other citizens of the policy he was engaged in politics - he decided state affairs; here in the agora, he could find out all the important news of the city. Originally, the agora was just an open area, devoid of any buildings whatsoever. Later, they began to arrange wooden or stone seats on the pei, rising in steps one above the other. On these benches the people were accommodated during the meetings. At an even later time (already at the end of the archaic period), special sheds were erected on the sides of the square - porticoes that protected people from the rays of the sun. The porticoes have become a favorite haven for petty traders, philosophers and all kinds of idle public. Government buildings of the policy were located directly on the agora or not far from it: the bouleuterium - the building of the city council (boule), get a place for the meetings of the ruling collegium of the pritans, the dicasterium - the courthouse, etc. On the agora, new laws and orders were exhibited for general information government.

Among the buildings of the archaic city, the temples of the main Olympic gods and famous heroes stood out for their size and splendor of decoration. Parts of the outer walls of the Greek temple were painted in bright colors and richly decorated with sculpture (also painted). The temple was considered the home of the deity, and it was present in it in the form of its image.

Initially, it was just a rough wooden idol, which had a very distant resemblance to a human figure.

However, by the end of the archaic era, the Greeks had already improved so much in plastic art that the statues of the gods carved by them from marble or cast in bronze could easily pass for living people (the Greeks imagined their gods as humanoid creatures endowed with the gift of immortality and superhuman power). On holidays, the god, dressed in his best clothes (for such occasions, each temple had a special wardrobe), crowned with a golden wreath, graciously accepted gifts and sacrifices from the citizens of the polis, who came to the temple in a solemn procession. Before approaching the shrine, the procession passed through the city to the sound of flutes with garlands of fresh flowers and lighted torches, accompanied by an armed escort. The festivities in honor of the deity of this polis were celebrated with special splendor.

Each polis had its own special patron or patroness. So, in Athens it was Pallas Athena. in Argos - Hera, in Corinth - Aphrodite, in Delphi - Apollo. The temple of the god-"city holder" was usually located in the city citadel, which the Greeks called the acropolis, that is, the "upper city". The state ka: sha of the polis was kept here. Here came the Fines levied for various crimes, and all other types of state income), In Athens already in the VI century. the top of the impregnable rock of the acropolis was crowned with the monumental temple of Athena, the main goddess of the city.

It is known how much athletic competition took place in the life of the ancient Greeks. From the earliest times in the Greek cities special areas for youth exercises were arranged - they were called gymnasiums. and palasters. Young men and adolescents spent whole dpi there, regardless of the season, diligently doing God, wrestling, fist fights, jumping, javelin and discus throwing. Not a single big holiday was complete without a massive athletic competition - agon, in which all free-born citizens of the policy, as well as specially invited foreigners, could take part.

Some agons, which were especially popular, turned into interpolis general Greek festivals. Such are the famous Olympic Games, which every four years attracted athletes and "fans" from all over the Greek world, including even the most remote colonies. The participating States prepared for them no less seriously than for the upcoming military campaign. Victory or defeat at Olympia was a matter of the prestige of each polis. Grateful fellow citizens showered the winner-olympionic with truly royal honors (sometimes they even dismantled the city wall to clear the way for the victor's triumphal chariot: it was believed that a person of such rank could not pass through an ordinary gate).

These are the main elements that made up the daily life of a citizen of a Greek polis in the archaic era, as well as in a later time: commercial transactions in the agora, speech in the popular assembly, participation in the most important religious ceremonies, athletic exercises and competitions.

And since all these types of spiritual and physical activity could only be done in the city, the Greeks could not imagine a normal human life outside the city walls. Only this way of life they considered worthy of a free man - a real Hellene, and in this special way of life they saw their main thing different from all the surrounding "barbarian" peoples.

Generated by the powerful surge in economic activity that accompanied the Great Colonization, the early Greek city, in turn, became an important factor in further economic and social progress. The urban way of life, with its characteristic intensive exchange of goods and other types of economic activity, in which masses of people of various origins took part, from the very beginning came into conflict with the then structure of Greek society, based on two main principles: the principle of class hierarchy, which separates all people on the "best" or "noble" and "worse" or "low-born", and the principle of strict isolation of separate clan unions both from each other and from the entire external world. In the cities, which began earlier, in connection with the resettlement to the colonies, the process of breaking the intergeneric barriers went on at an especially fast pace. People who belonged to different clans, philae and phratries, not only now live side by side, in the same neighborhoods, but also enter into business and simply friendly contacts, enter into marriage alliances. Gradually, the line begins to blur, separating the old clan nobility from wealthy merchants and landowners who came from the common people. There is a fusion of these two strata into a single ruling class of slave owners. The main role in this process was played by money - the most accessible and most mobile type of property. This was well understood by the contemporaries of the events described. “Money is held in high esteem. Wealth has mixed the breeds, ”exclaims the Megarian poet of the 6th century. Theognides.

The growth of cities is associated with progress in the field of intra-polis and international law. The need for further development of commodity-money relations, rallying the entire population of the policy into a single civil collective was difficult to reconcile with the traditional principles of tribal law and morality, in accordance with which every stranger - a native of a foreign clan or phratry - was perceived as a potential enemy to be destroyed or turned into slave. In the archaic era, these views gradually begin to give way to broader and more humane views, according to which there is a kind of divine justice that applies equally to all people, regardless of their clan or tribal affiliation. We come across such a representation already in The Works and Days of Hesiod, the Boeotian poet of the 8th century. BC e., although it is completely alien to his closest predecessor, Homer. Gods, in the understanding of Hesiod, closely follow the right and wrong deeds of people. For this purpose, “three myriads of immortal guards ... spies of right and evil human deeds were sent to earth, they roam the world everywhere, clothed with foggy haze” (Hereinafter, translations by V.V. Veresaev.).

The main guardian of law is the daughter of Zeus - the goddess Dike ("Justice"). The most ancient collections of laws attributed to famous legislators: Drakont, Zalevk, Harond, and others testify to the real progress of public legal consciousness. Judging by the surviving passages, these codes were still very imperfect and contained many archaic legal norms and customs: at the core of the Drakont's laws and their like were a record of customary law already in existence. Many of these laws are rooted in the depths of the primitive era, such as the exotic custom of bringing to justice “murdered” animals and inanimate objects, which we encounter in one of the fragments of the Draconian laws that have come down to us. At the same time, the very fact of the registration of law cannot but be assessed as a positive shift, since it testifies to the desire to put a limit to the arbitrariness of influential families and clans and to achieve submission of the clan to the judicial authority of the policy. Recording, laws and the introduction of correct legal proceedings contributed to the elimination of such ancient customs as blood feud or the bribe for murder. Now the murder is no longer considered a private affair of two families: the family of the killer and the family of his victim. The entire community, represented by its judicial authorities, is involved in resolving the dispute.

The advanced norms of morality and law apply in this era not only to compatriots, but also to foreigners, citizens of other policies. The corpse of the slain enemy was no longer subjected to abuse (cf., for example, the Iliad, where Achilles outraged the body of the deceased Hector), but is given to relatives for burial. Free Hellenes captured in war, as a rule, are not killed or turned into slaves, but returned to their homeland for ransom. Measures are being taken to eradicate sea piracy and robbery on land. Separate policies conclude agreements with each other, guaranteeing personal safety and the inviolability of citizens' property if they find themselves on a foreign territory. These steps towards rapprochement were prompted by a real need for closer economic and cultural contacts. To a certain extent, this led to overcoming the former isolation of individual cities and the gradual development of common Greek, or, as they said, Pan-Hellenic, patriotism. However, things did not go beyond these first attempts. The Greeks did not become a single people.

It was the cities that were the main centers of the achievements of advanced culture in the archaic period. A new writing system - the alphabet - became widespread here.

It was much more convenient than the syllabic writing of the Mycenaean era: it consisted of only 24 characters, each of which had a firmly established phonetic meaning. If in the Mycenaean society, literacy was available only to a few initiates who were part of a closed group of professional scribes, now it becomes the common property of all citizens of the polis (everyone could master the elementary skills of writing and reading in elementary school). For the first time, the new writing system was a truly universal means of transmitting information, which could equally well be used in business correspondence and for writing lyric poems or philosophical aphorisms. All this led to the rapid growth of literacy among the population of the Greek city-states and, undoubtedly, contributed to the further progress of culture in all its main areas.

However, all this progress, as is usually the case in history, had its downside, shadow side. The rapid development of commodity-money relations, which gave rise to the first cities with their advanced, life-affirming culture, had a negative impact on the position of the Greek peasantry. The agrarian crisis, which was the main reason for the Great Colonization, not only did not subside, but, on the contrary, began to rage with even greater force. Almost everywhere in Greece, we see the same bleak picture: the peasants are being ruined by the masses, deprived of their "paternal plots" and join the ranks of farm laborers - fetas. Describing the situation in Athens at the turn of the 7th-6th centuries. BC BC, before the reforms of Solon, Aristotle wrote: “It must be borne in mind that in general the state system was oligarchic, but the main thing was that the poor were enslaved not only themselves, but also their children and wives. They were called pelates and six-handed people, because on such lease conditions they cultivated the fields of the rich (It is not clear with the dog what Aristotle wanted to say with this phrase. Six-handed people could give the landowner either 5/6 or 1/6 of the harvest. The latter seems more likely, since with the existing agricultural technique, it is unlikely that the peasant could feed his family with one-sixth of the harvest from a plot of such size that he could work with his wife and children.). All the land in general was in the hands of a few. At the same time, if these poor people did not pay rent, they could be taken into bondage both themselves and their children. Yes, and all loans were secured by personal bondage up to the time of Solon. " To one degree or another, this characteristic is applicable to all other regions of the then Greece.

The radical breakdown of the habitual way of life had a very painful effect on the consciousness of the people of the archaic era. In Hesiod's poem Works and Days, the entire history of mankind is presented as a continuous decline and a movement backwards from the best to the worst. On earth, according to the poet, four human generations have already changed: gold, silver, copper and the generation of heroes. Each of them lived worse than the previous one, but the most difficult fate went to the fifth, iron generation of people, to which Hesiod himself reckons. “If I could not live with the generation of the fifth century! - the poet exclaims sadly. - Before he died, I would like to be born later ”.

The consciousness of his helplessness in the face of the "king-darling" ("Tsars" (basilei) in the Lord, as well as in Homer, are representatives of the local clan nobility, standing at the head of the community.), Apparently, especially oppressed the poet-peasants and on the. This is evidenced by the "Fable of the Nightingale and the Hawk" included in Hesiod's poem:

Now I will tell the fable to the kings how unreasonable they are. This is what a nightingale once said to a loose hawk. Claws plunging into him and carrying him in high clouds. The nightingale squeaked pitifully, pierced by crooked claws. The same imperiously addressed him with such a speech: “What are you, unfortunate, squeaking? After all, I am much stronger than you! How do you not sing, but I will take you wherever I please, And I can dine with you, and set you free. He has no reason who wants to measure himself with the strongest; Neither will he defeat him - he will only add grief to the unnzhenie! " That's what the swift hawk said, long-winged bird.

At the time when Hesiod created his "Works and Days", the power of the clan nobility in most Greek city-states remained unshakable.

After some hundred years, the picture changes radically.

We learn about this from the poems of another poet, a native of Megara Theognis. Theognis, although by birth he belonged to the highest nobility, feels very insecure in this changing world before our eyes and, like Hesiod, is inclined to be very pessimistic about his era. He is tormented by the consciousness of the irreversibility of social changes taking place around him:

Our city is still a city, oh Kirn, but people are different,

Who knew neither laws nor justice, Who dressed his body with worn-out goat fur

And outside the city wall he grazed like a wild deer.

Became noble from now on.

And the people who were noble,

Low steel. Well, who could have endured all this?

Theognides' poems show that the process of property stratification of the community affected not only the peasantry, but also the nobility. Many aristocrats, overwhelmed by the thirst for profit, invested their fortune in various commercial enterprises and speculations, but, lacking sufficient practical acumen, they went bankrupt, giving way to more tenacious and resourceful people from the lower classes, who, thanks to their wealth, now rise to the very top of the social ladder. These "upstarts" evoke in the soul of the poet-aristocrat wild anger and hatred. In his dreams, he sees the people returned to their former, half-slave state:

With a firm foot, step on the chest of the imaginative rabble, Beat it with a brass butt, bend your neck under the yoke! .. No under the all-seeing sun, there is no wide people in the world, To voluntarily endure the strong reins of the masters ...

Reality, however, shatters these illusions of the herald of aristocratic reaction. Going back is no longer possible, and the poet is aware of this.

Theognides' poems captured the height of the class struggle, the moment when the mutual hostility and hatred of the fighting parties reached their highest point. A powerful democratic movement swept at this time the cities of the Northern Peloponnese, including the hometown of Theognis Megara, also Attica, the island policies of the Aegean Sea, the Ionian cities of Asia Minor and even the remote western colonies of Italy and Sicily.

Everywhere democrats put forward the same slogans: "Redistribution of land and cancellation of debts", "Equality of all citizens of the policy before the law") (isonomia), "Transfer of power to the people" (democracy). This democratic movement was heterogeneous in its social composition. It was attended by rich merchants from the common people, and wealthy peasants, and artisans, and the disadvantaged masses of the rural and urban poor. If the former sought, first of all, political equality with the old nobility, the latter were much more attracted by the idea of universal property equality, which meant, under the conditions of the time, a return back to the traditions of the communal clan system, to regular redistribution of land. In many places, desperate peasants tried to put into practice the patriarchal utopia of Hesiod and lead humanity back to the "golden age." Encouraged by this idea, they seized the property of the rich and nobility and divided it among themselves, threw the hated mortgage pillars from their fields (These pillars were erected by the creditor on the debtor's field as a sign that the field was a pledge of debt payment and could be taken away in case of non-payment. ), burned debt books of usurers. Defending their property, the rich are increasingly using terror and violence, and thus the class enmity that has accumulated over the centuries develops into a real civil war. Rebellions and coups d'etat, accompanied by brutal killings, mass expulsions and confiscation of the property of the defeated, became at this time a common occurrence in the life of the Greek city-states. Theognides, in one of his elegies, addresses the reader with a warning:

Let our city rests in complete silence, - Believe me, she can reign in the city for a short time. Where bad people begin to strive for that, In order to derive benefit for themselves from the passions of the people. For from here - uprisings, civil wars, murders, Also monarchs - protect us from them, fate!

The mention of monarchs in the last line is quite symptomatic:

in many Greek states, the socio-political crisis that sometimes lasted for decades was resolved by the establishment of a regime of personal power.

The polis community, exhausted by endless internal unrest and strife, could no longer resist the claims of influential persons for sole power, and the dictatorship of a "strong man" was established in the city, who ruled regardless of the law and traditional institutions: council, popular assembly, etc. The Greeks called such usurpers tyrants (the word itself was borrowed by the Greeks from the Lydian language and initially had no abusive meaning.), Opposing them to the ancient kings - Basilei, who ruled on the basis of hereditary law or popular election. Having seized power, the tyrant began reprisals against his political opponents. They were executed without trial or investigation. Entire families and even clans were sent into exile, and their property passed to the tyrant's treasury. In the later historical tradition, mainly hostile to tyranny, the very word "tyranny" has become in Greek synonymous with merciless bloody arbitrariness. Most often, the victims of repression were people from old aristocratic families. The spearhead of the terrorist policy of the tyrants was directed against the clan nobility. Not content with the physical extermination of the most prominent representatives of this social group, tyrants infringed upon its interests in every possible way, forbidding aristocrats to do gymnastics, gather for joint meals and drinks, acquire slaves and luxury goods. The nobility, being the most organized and at the same time the most influential and wealthy part of the community, represented the greatest danger to the tyrant's sole power. From this side, he constantly had to expect conspiracies, assassination attempts, riots.

The relationship between the tyrant and the people was different. Many tyrants of the archaic era began their political careers as prostates, that is, the leaders and defenders of the demos. The famous Pisistratus, who seized power over Athens in 562 BC. e., relied on the support of the poorest part of the Athenian peasantry, which lived mainly in the inner mountainous regions of Attica. The "guard" of the tyrant, given to Peisistratus at his request by the Athenian people, was composed of a detachment of three hundred men armed with clubs - the usual weapon of the Greek peasantry in that troubled time. With the help of these "club-bearers" Pisistratus seized the Athenian acropolis and thus became the master of the situation in the city. While in power, the tyrant placated the demos with gifts, free treats, and entertainment during the holidays. Thus, Pisistratus introduced a cheap agricultural loan in Athens, lending to needy peasants with implements, seeds, cattle. He instituted two new popular festivals; Great Panathenes and City Dionysias and celebrated them with extraordinary splendor (The program of City Dionysias included theatrical performances. According to legend, in 536 BC, under Peisistratus, the first tragedy in the history of Greek theater was staged.). The desire to achieve popularity among the people was also dictated by the measures attributed to many tyrants for the improvement of cities: the construction of water pipes and fountains, the construction of new magnificent temples, porticos on the agora, port buildings, etc. All this, however, does not give us the right to count the tyrants themselves "Fighters" for the people's cause. The main goal of the tyrants was the all-round strengthening of dominion over the polis and, in the long term, the creation of a hereditary dynasty. The tyrant could carry out these plans only by breaking the resistance of the nobility. For this he needed the support of the demos, or at least benevolent neutrality on his part. In their "love for the people" tyrants usually did not go further than insignificant handouts and demagogic promises to the crowd. None of the tyrants we know tried to implement in practice the main slogans of the democratic movement: "Redistribution of land" and "Cancellation of debts." None of them did anything to democratize the political system of the polis. On the contrary, constantly in need of money to pay salaries to mercenaries, for their construction enterprises and other needs, tyrants levied previously unknown taxes on their subjects. So, under Pisistratus, the Athenians annually deducted 1/10 of their income to the tyrant's treasury. On the whole, tyranny not only did not contribute to the further development of the slave-owning state, but, on the contrary, hindered it.

The tactics used by tyrants in relation to the masses can be defined as the "carrot and stick policy."

Flirting with the demos and trying to win him over as a possible ally in the fight against the nobility, tyrants were at the same time afraid of the people. To protect themselves from this side, they often resorted to disarming the citizens of the polis and at the same time surrounded themselves with hired bodyguards from among foreigners or released slaves. Any gathering of people in a city street or square aroused suspicion in the tyrant; it seemed to him that the citizens were up to something, preparing a mutiny or an assassination attempt; the tyrant's dwelling was usually located in the city citadel - on the acropolis. Only here, in his fortified nest, he could feel at least relatively safe.

Naturally, in such conditions, there was no really strong alliance between the tyrant and the demos and could not be. The only real support of the regime of personal power in the Greek city-states, in essence, was the mercenary guard of the tyrants. Tyranny left a noticeable mark on the history of early Greece. The colorful figures of the first tyrants - Periander, Peisistratus, Polycrates, and others - invariably attracted the attention of later Greek historians. From generation to generation, legends about their extraordinary power and wealth, about their superhuman luck, which aroused the envy of even the gods themselves, were passed down - such is the well-known legend about the Polycratic ring, preserved by Herodotus (Tradition says that the tyrant of the island of Samos, who was visiting Polycrates, The Egyptian king advised him to sacrifice the most expensive that he had, so that the gods would not envy his happiness. Polycrates threw his ring into the sea, but the next day the fisherman brought him a big fish as a gift, and the thrown ring was found in her belly. left Polycrates, considering him doomed, and soon he really died.). In an effort to add more splendor to their reign and perpetuate their name, many tyrants attracted prominent musicians, poets, and artists to their courts. Such Greek city-states as Corinth, Sikion, Athens, Samos, Miletus, became rich, prosperous cities under the rule of tyrants, were adorned with new magnificent buildings. Some of the tyrants were quite successful in their foreign policy.

Periander, who ruled Corinth from 627 to 585 BC e., managed to create a large colonial power, stretching from the islands of the Ionian Sea to the shores of the Adriatic. Famous tyrant of the island

Samos Polycrates in a short time subordinated to his dominion most of the island states of the Aegean Sea. Pisistratus successfully fought for the seizure of an important sea route that connected Greece through a corridor of straits and the Sea of Marmara with the Black Sea region. Nevertheless, the contribution of tyrants to the socio-economic and cultural development of archaic Greece cannot be exaggerated. In this matter, we can well rely on that sober and impartial assessment of tyranny, which was given by the greatest of the Greek historians, Thucydides. “All the tyrants who were in the Hellenic states,” he wrote, “turned their concerns exclusively to their own interests, to the safety of their personality and to the exaltation of their home. Therefore, in governing the state, they were primarily, as far as possible, concerned about taking measures for their own security; they did not accomplish a single remarkable deed, except perhaps the wars of individual tyrants with the border inhabitants. " But having a solid social support among the masses, tyranny could not become a stable form of government in the Greek polis. Later Greek historians and philosophers, for example Herodotus, Plato, Aristotle, saw in tyranny an abnormal, unnatural state of the state, a kind of polis disease caused by political unrest and social upheaval, and were sure that this state could not last long.

Indeed, only a few of the Greek tyrants of the archaic period managed not only to retain the throne they had seized, but also to pass it on to their children (The longest was the reign of the Orphagorid dynasty in Sicyon (670-510 BC). the second place is taken by the Corinthian Cypselides (657-583 BC), the third - the Pisistratis (560-510 BC)).

Tyranny only weakened the ancestral nobility, but could not completely break its power, and probably did not strive for this. In many city-states, following the overthrow of the tyrapy, outbreaks of acute struggle are again observed. But in the cycle of civil wars, a new type of state is gradually emerging - the slave-owning policy.

The formation of the polis was the result of the persistent reformatory activities of many generations of Greek legislators. We know almost nothing about most of them. (Ancient tradition has brought to us only a few names, among which the names of two prominent Athenian reformers - Solon and Cleisthenes and the great Spartan legislator Lycurgus - are especially prominent. As a rule, the most significant transformations were carried out in an environment of acute political crisis. A number of cases are known when citizens of a state, driven to despair by endless strife and unrest and who did not see any other way out of the situation, chose one of their midst as mediator and conciliator.

Solon was one such conciliator. Elected in 594 BC NS. to the post of the first archon (Archons (literally, "commander") - the ruling collegium of officials, consisting of nine people. The first archon was considered the chairman of the collegium. A year was designated by his name in Athens.) with the rights of a legislator, he developed and implemented a broad program of social - economic and political transformations, the ultimate goal of which was to restore the unity of the polis community, split by civil strife into warring political groupings. The most important among Solon's reforms was the radical reform of debt law, which went down in history under the figurative name of “shaking off the burden” (seisakhteya). Solon did in fact throw off the hated burden of debt bondage from the shoulders of the Athenian people, declaring all debts and the interest accumulated on them invalid and forbidding self-mortgage transactions for the future. Seysakhteya saved the peasantry of Attica from enslavement and thereby made possible the further developed democracies in Athens. Subsequently, the legislator himself proudly wrote about this service of his to the Athenian people: What kind of one am I?

About that all the best could be said from Mother Black Earth, Pillars set

A slave before

(Translation by S.I.Radtsig.).

did not fulfill those tasks, then he rallied the people,

before the Time of the court of the Olympians, the highest - from which I then took off a lot of debt,

now free. Having freed the Athenian demos from the debt burdening him, Solon, however, refused to fulfill his other demand - to redistribute the land. According to Solon himself, his intention was not at all "to give the bad and the noble an equal share in the gains of relatives," that is, to completely equalize the nobility and the common people in property and social terms. Solon tried only to stop the further growth of large landholdings and thereby put a limit on the dominance of the nobility in the economy of Athens. Solon's law is known, which forbade the acquisition of land in excess of a certain rate. Obviously, these measures were successful, since later, during the 6th and 5th centuries. BC e., Attica remained predominantly a country of medium and small landownership, in which even the largest slaveholding farms exceeded several tens of hectares in area.

Another important step towards democratizing the Athenian state and strengthening its internal unity was made at the end of the 6th century. (between 509 and 507) Cleisthenes (Between Solon and

Cleisthenes in Athens was ruled by the tyrant Pisistratus, and then by his sons. Tyranny was eliminated in 510 BC. NS.). If Solop's reforms undermined the economic power of the nobility, then Cleisthenes, although he himself came from a noble family, went even further. The main support of the aristocratic regime in Athens, as well as in all other Greek states, were clan associations - the so-called phylae and phratries. Since ancient times, the entire Athenian demos was divided into four phylae, each of which included three phratries. At the head of each phratry was a noble family in charge of its cult affairs. Ordinary members of the phratry were obliged to submit to the religious and political authority of their "leaders", supporting them in all their endeavors.

Occupy a dominant position in the tribal unions, the aristocracy kept the entire mass of the demos under its control. It was against this political organization that Klisphep directed his main blow. He introduced a new, purely territorial system of administrative division, distributing all citizens into ten fils and one hundred smaller units - demes. The Philae established by Cleisthenes had nothing to do with the old ancestral Philae.

Moreover, they were drawn up in such a way that persons belonging to the same clans and phratries would henceforth be politically disunited, living in different territorial-administrative districts. Cleisthenes, in the words of Aristotle, "mixed the entire population of Attica", regardless of its traditional political and religious ties. Thus, he managed to simultaneously solve three important problems: 1) the Athenian demos, and above all the peasantry, which constituted a very significant and at the same time the most conservative part of it, was freed from the ancient clan traditions on which the political influence of the nobility was based; 2) the often arising feuds between individual clan unions, which threatened the internal unity of the Athenian state, were terminated; 3) those who had previously stood outside the phratries and phil and, therefore, did not enjoy civil rights were involved in political life. Cleisthenes' reforms complete the first phase of the struggle for democracy in Athens. In the course of this struggle, the Athenian demos achieved great success, grew politically and strengthened. The will of the demos, expressed by a general vote in the assembly of the people (ecclesia), acquires the force of a law binding on all. All officials, not excluding the highest ones - archons and strategists (Generals in Athens were called strategists who commanded the army and navy. A collegium of ten strategists was established by Cleisthenes.) Are elected and are obliged to report to the people in their actions, and in that case, if any wrongdoing is committed on their part, they can be subjected to severe punishment.

The council of five hundred (boule) created by Cleisthenes and the jury (helium) established by Solon worked hand in hand with the popular assembly. The Council of Five Hundred performed the functions of a kind of presidium at the people's assembly, engaged in preliminary discussion and processing of all proposals and bills that were then submitted for final approval to the ecclesia. Therefore, the decrees of the national assembly in Athens usually began with the formula: "The council and the people decided." As for helium, it was the highest court in Athens, to which all citizens could complain about unfair decisions of officials. Both the council and the jury were drawn by lot for ten philes instituted by Cleisthenes. Thanks to this, ordinary citizens could also get into their composition on an equal basis with representatives of the nobility. In this they fundamentally differed from the old aristocratic council and court - the Areopagus.