Foreign literature of the XX century (Edited by V.M. Tolmachev) XV

Read also

France is a country ahead of others. It was here that the first revolutions took place, and not only social, but also literary, which influenced the development of art in the whole world. and poets achieved unprecedented heights. It is also interesting that it was in France that the work of many geniuses was appreciated during their lifetime. Today we will talk about the most significant writers and poets of the 19th - early 20th centuries, and also open the curtain over the interesting moments of their lives.

Victor Marie Hugo (1802-1885)

It is unlikely that other French poets can match the scope of Victor Hugo. A writer who was not afraid to raise acute social topics in his novels, and at the same time a romantic poet, he lived a long life full of creative successes. Hugo as a writer was not only recognized during his lifetime - he became rich by doing this craft.

After Notre Dame Cathedral, his fame only increased. Are there many writers in the world who could live 4 years on the street? At 79 years of age (on the birthday of Victor Hugo), a triumphal arch was erected on Eylau Avenue - in fact, under the writer's windows. 600,000 admirers of his talent passed through it that day. The street was soon renamed Avenue Victor-Hugo.

After himself, Victor Marie Hugo left not only wonderful works and a large inheritance, 50,000 francs of which was bequeathed to the poor, but also a strange clause in the will. He ordered to rename the capital of France - Paris - in Guugopolis. Actually, this is the only item that has not been fulfilled.

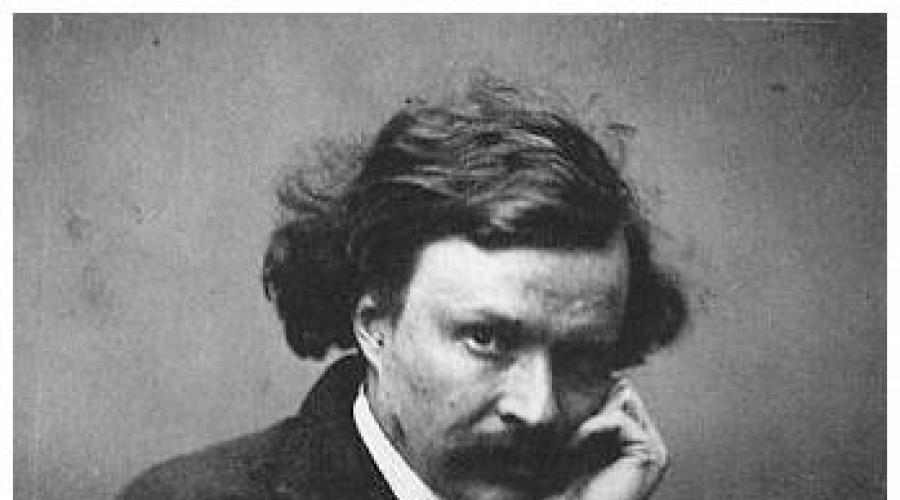

Théophile Gaultier (1811-1872)

When Victor Hugo fought classicist criticism, he was one of its brightest and most loyal supporters. French poets received an excellent replenishment of their ranks: Gaultier not only mastered the writing technique impeccably, but also opened a new era in French art, which subsequently influenced the whole world.

Having sustained his first collection in the best traditions of the romantic style, Théophile Gaultier at the same time excluded traditional themes from his poems and changed the vector of poetry. He did not write about the beauty of nature, eternal love and politics. Moreover, the poet proclaimed the technical complexity of the verse as the most important component. This meant that his poems, while remaining romantic in form, were not essentially them - feelings gave way to form.

The latest collection, "Enamels and Cameos", which is considered the pinnacle of Théophile Gaultier's creativity, also includes the manifesto of the "Parnassian school" - "Art". He proclaimed the principle of "art for art's sake", which the French poets accepted unconditionally.

Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891)

The French poet Arthur Rimbaud inspired more than one generation with his life and poetry. On several occasions he ran away from home to Paris, where he met Paul Verlaine, sending him the poem "The Drunken Ship". The friendship between the poets very soon developed into a love affair. This is what caused Verlaine to leave the family.

During Rimbaud's lifetime, only 2 collections of poetry were published and, separately, the debut verse "The Drunken Ship", which immediately brought him recognition. Interestingly, the poet's career was very short: he wrote all his poems between the ages of 15 and 21. And after that Arthur Rimbaud simply refused to write. Absolutely. And he became a merchant, selling spices, weapons and ... people until the end of his life.

Famous French poets and Guillaume Apollinaire are the recognized heirs of Arthur Rimbaud. His work and persona inspired Henry Miller for his essay "Time for Assassins", and Patti Smith constantly talks about the poet and quotes his poems.

Paul Verlaine (1844-1896)

French poets of the late 19th century chose Paul Verlaine as their "king", but there was little from the king: a rowdy and a reveler, Verlaine described the unsightly side of life - dirt, darkness, sins and passions. One of the "fathers" of impressionism and symbolism in literature, the poet wrote poetry, the beauty of the sound of which no translation can convey.

No matter how vicious the French poet was, Rimbaud played a huge role in his future destiny. After meeting the young Arthur, Paul took him under his wing. He looked for housing for the poet, even rented a room for him for some time, although he was not wealthy. Their love affair lasted for several years: after Verlaine left the family, they traveled, drank and indulged in pleasure as best they could.

When Rimbaud decided to leave his lover, Verlaine shot him in the wrist. Although the victim refused the application, Paul Verlaine was sentenced to two years in prison. After that, he never recovered. Due to the impossibility of abandoning the society of Arthur Rimbaud, Verlaine was never able to return to his wife - she achieved a divorce and ruined him completely.

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918)

The son of a Polish aristocrat, born in Rome, Guillaume Apollinaire belongs to France. It was in Paris that he lived his youth and adulthood, right up to his death. Like other French poets of that time, Apollinaire was looking for new forms and possibilities, he strove for shocking - and succeeded in this.

After the publication of prose works in the spirit of deliberate immoralism and a mini-collection of poetry "Bestiary, or Orpheus's cortege", published in 1911, Guillaume Apollinaire published the first full-fledged poetry collection "Alcohol" (1913), which immediately attracted attention by the lack of grammar, baroque imagery and tone drops.

The collection of "Caligrams" went even further - all the poems that were included in this collection are written in an amazing way: the lines of the works are lined up in various silhouettes. The reader sees a woman in a hat, a dove flying over a fountain, a vase of flowers ... This form conveyed the essence of the verse. The method, by the way, is far from new - the English began to give form to poetry in the 17th century, but at that moment Apollinaire anticipated the emergence of "automatic writing", which the surrealists loved so much.

The term "surrealism" belongs to Guillaume Apollinaire. He appeared after the staging of his "surrealistic drama" "Sostsy Tiresias" in 1917. The circle of poets led by him at that time began to be called surrealists.

André Breton (1896-1966)

The meeting with Guillaume Apollinaire became a landmark. It happened at the front, in a hospital, where young Andre, a physician by training, served as an orderly. Apollinaire received a concussion (a shell fragment hit the head), after which he never recovered.

Since 1916 André Breton takes an active part in the work of the poetic avant-garde. He met Louis Aragon, Philippe Soupot, Paul Eluard, discovered the poetry of Lautréamont. In 1919, after the death of Apollinaire, outrageous poets began to organize around André Breton. Also this year comes out a joint essay "Magnetic Fields" with Philippe Soupaud, written according to the "automatic writing" method.

Since 1924, after the proclamation of the first Manifesto of Surrealism, André Breton becomes the head of the movement. In his house on Avenue Fontaine, the Bureau of Surrealist Studies opens, magazines begin to be published. This was the beginning of a truly international movement - similar offices began to open in many cities around the world.

The French communist poet André Breton actively encouraged his supporters to join the Communist Party. He believed in the ideals of communism so much that he even deserved to meet with Leon Trotsky in Mexico (although at that time he was already expelled from the Communist Party).

Louis Aragon (1897-1982)

A loyal ally and comrade-in-arms of Apollinaire, Louis Aragon became the right hand for André Breton. French poet, communist until his last breath, in 1920 Aragon published the first collection of poems "Fireworks", written in the style of surrealism and dadaism.

After the poet entered the Communist Party in 1927, together with Breton, his work was transformed. He became in some way the “voice of the party”, and in 1931 he was prosecuted for the poem “The Red Front”, imbued with a dangerous spirit of incitement.

Peru Louis Aragon also belongs to "History of the USSR". He defended the ideals of communism until the end of his life, although his last works returned a little to the traditions of realism, not tinged with "red".

International Day of Francophonie is celebrated annually on March 20. This day is dedicated to the French language, which is spoken by more than 200 million people around the world.

We took advantage of this occasion and propose to recall the best French writers of our time, representing France in the international book arena.

Frederic Beigbeder ... Prose writer, publicist, literary critic and editor. His literary works, with descriptions of modern life, man's throwing in the world of money and love experiences, very quickly won fans around the world. The most sensational books "Love lives for three years" and "99 francs" were even filmed. The novels "Memories of an Unreasonable Young Man", "Vacation in a Coma", "Tales under Ecstasy", "Romantic Egoist" also brought the writer well-deserved fame. Over time, Beigbeder founded his own literary prize, the Flora Prize.

Michelle Houellebecq ... One of the most widely read French writers of the early 21st century. His books have been translated into a good three dozen languages, he is extremely popular among young people. Perhaps this is due to the fact that the writer was able to touch the painful points of modern life. His novel Elementary Particles (1998) won the Grand Prix, Map and Territory (2010) - the Goncourt Prize. They were followed by "Platform", "Lanzarote", "Island Opportunity" and others, and each of these books became a bestseller.

New novel of the writer"Obedience" tells about the collapse in the near future of the modern political system of France. The author himself defined the genre of his novel as "political fiction." The action takes place in 2022. A Muslim president comes to power in a democratic way, and the country begins to change before our eyes ...

Bernard Verber ... Cult science fiction writer and philosopher. His name on the cover of the book means only one thing - a masterpiece! The total world circulation of his books is over 10 million! The writer is better known for the trilogies "Ants", "Thanatonauts", "We, the Gods" and "Third Humanity". His books have been translated into many languages, and seven novels have become bestsellers in Russia, Europe, America and Korea. On the account of the author - a lot of literary prizes, incl. Jules Verne Prize.

One of the most sensational books of the writer -"Empire of Angels" where fantasy, mythology, mysticism and the real life of the most ordinary people are intertwined. The main character of the novel goes to heaven, undergoes the "last judgment" and becomes an angel on Earth. According to heavenly rules, he is given three human clients, whose lawyer he must later become at the Last Judgment ...

Guillaume Musso ... A relatively young writer, very popular among French readers. Each of his new works becomes a bestseller, films are made based on his works. Deep psychologism, piercing emotionality and vivid figurative language of books fascinate readers all over the world. His adventure psychological novels are set all over the world - in France, the USA and other countries. Following the heroes, the readers set out on adventures full of dangers, investigate riddles, plunge into the abyss of the heroes' passions, which, of course, gives rise to a glimpse into their inner world.

At the heart of the new novel of the writer"Because I love you" - the tragedy of one family. Mark and Nicole were happy until their little daughter - the only, long-awaited and adored child - disappeared ...

Mark Levy . One of the most famous novelist writers, whose works have been translated into dozens of languages and published in huge editions. The writer is a laureate of the Goya National Prize. Steven Spielberg paid two million dollars for the right to film his first novel, Between Heaven and Earth.

Literary critics note the versatility of the author's work. In his books - "Seven Days of Creation", "Meet Again", "Everyone Wants to Love", "Leave to Return", "Stronger than Fear", etc. - the theme of disinterested love and sincere friendship, the secrets of old mansions and intrigue is often encountered , reincarnation and mysticism, unexpected plot twists.

Writer's new book"She and he" is one of the best novels at the end of 2015. This is a romantic story about an irresistible and unpredictable love.

Anna Gavalda

... The famous writer who conquered the world with her novels and their refined, poetic style. She is called “the star of French literature” and “the new Françoise Sagan”. Her books have been translated into dozens of languages, awarded with a whole constellation of awards, plays are staged and films based on them. Each of her works is a story about love and how it adorns every person.

In 2002, the first novel of the writer was published - "I loved her, I loved him." But this was all just a prelude to the real success that the book brought her."Just together"

, which eclipsed even the novel "Da Vinci Code" by Brown in France.This is an amazingly wise and kind book about love and loneliness, about life and, of course, happiness.

Hello everyone! Came across a list of the 10 best French novels. I, frankly, did not work out with the French, so I will ask the connoisseurs - how do you like the list that you have read / did not read from it, what would you add / remove to it?

1. Antoine de Saint-Exupery - "The Little Prince"

The most famous work of Antoine de Saint-Exupery with author's drawings. A wise and "humane" fairy tale-parable, which simply and soulfully speaks about the most important things: about friendship and love, about duty and loyalty, about beauty and intolerance towards evil.

“We all come from childhood,” the great Frenchman reminds us and introduces us to the most mysterious and touching hero of world literature.

2. Alexandre Dumas - "The Count of Monte Cristo"

The plot of the novel was gleaned by Alexandre Dumas from the archives of the Parisian police. The true life of François Picot, under the pen of the brilliant master of the historical and adventure genre, turned into a gripping story about Edmond Dantes, a prisoner of the Château d'If. Having made a daring escape, he returns to his hometown to administer justice - to take revenge on those who destroyed his life.

3. Gustave Flaubert - "Madame Bovary"

The main character, Emma Bovary, suffers from the inability to fulfill her dreams of a brilliant, social life, full of romantic passions. Instead, she is forced to drag out the monotonous existence of the wife of a poor provincial doctor. The painful atmosphere of the boondocks strangles Emma, but all her attempts to break out of the joyless world are doomed to failure: a boring husband cannot satisfy the needs of his wife, and her outwardly romantic and attractive lovers are actually self-centered and cruel. Is there a way out of life's impasse? ..

4. Gaston Leroux - The Phantom of the Opera

“The Phantom of the Opera really existed” - one of the most sensational French novels of the turn of the XIX-XX centuries is devoted to the proof of this thesis. It belongs to the pen of Gaston Leroux, the master of the police novel, the author of the famous Mystery of the Yellow Room, The Scent of the Lady in Black. From the first to the last page, Leroux keeps the reader in suspense.

5. Guy de Maupassant - "Dear friend"

Guy de Maupassant is often called the master of erotic prose. But Dear Friend (1885) goes beyond this genre. The story of the career of an ordinary seducer and play-off of life, Georges Duroy, developing in the spirit of an adventure novel, becomes a symbolic reflection of the spiritual impoverishment of the hero and society.

6. Simone De Beauvoir - "Second Sex"

Two volumes of the book "The Second Sex" by the French writer Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) - "a born philosopher", according to her husband J.-P. Sartre, - are still considered the most complete historical and philosophical study of the entire complex of problems associated with women. What is “female destiny”, what is behind the concept of “natural purpose of sex”, how and why the position of a woman in this world differs from the position of a man, is a woman capable, in principle, to take place as a full-fledged person, and if so, in what conditions, what circumstances limit a woman's freedom and how to overcome them.

7. Scholerlot de Laclos - "Dangerous Liaisons"

Dangerous Liaisons, one of the most striking novels of the 18th century, is the only book by Chauderlos de Laclos, a French artillery officer. The heroes of the erotic novel, the Viscount de Valmont and the Marquis de Merteuil, are plotting a sophisticated intrigue, wanting to take revenge on their opponents. Having developed a cunning strategy and tactics of seduction of the young girl Cecile de Volange, they masterly play on human weaknesses and shortcomings.

8. Charles Baudelaire - Flowers of Evil

Among the masters of world culture, the name of Charles Baudelaire shines like a bright star. This book includes a collection of the poet "Flowers of Evil", which made his name famous, and a brilliant essay "School of the Gentiles." The book is preceded by an article by the remarkable Russian poet Nikolai Gumilyov, and the rarely published essay on Baudelaire by the outstanding French poet and thinker Paul Valery ends.

9. Stendhal - "Parma monastery"

The novel, written by Stendhal in just 52 days, received worldwide recognition. The dynamism of the action, the intriguing course of events, the dramatic denouement combined with the depiction of strong characters capable of anything for the sake of love are the key moments of the work that never cease to excite the reader until the last lines. The fate of Fabrizio, the protagonist of the novel, a freedom-loving young man, is filled with unexpected ups and downs that take place during a period of historical turning point in Italy at the beginning of the 19th century.

10. André Gide - The Counterfeiters

A novel that is significant both for the work of André Gide and for French literature of the first half of the 20th century in general. A novel that largely predicted the motives that later became the main ones in the work of the existentialists. The tangled relationships of three families - representatives of the big bourgeoisie, united by crime, vice and a labyrinth of self-destructive passions - become the background for the story of the growing up of two young men - two childhood friends, each of whom will have to go through their own, very difficult school of "education of feelings."

Xv

FRENCH LITERATURE

SECOND HALF OF THE XX CENTURY

Sociocultural situation in France after 1945. The concept of "engaged literature". - Sartre and Camus: a controversy between two writers; artistic features of the post-war existentialist novel; development of existentialist ideas in drama ("Behind a Closed Door", "Dirty Hands", "The Recluses of Altona" by Sartre and "Fair" by Camus). - Ethical and aesthetic personalism program; Carol's work: poetics of the novel "I will live by the love of others", essays. - The concept of art as "anti-destiny" in Malraux's later work: the novel "The Hazel Trees of Altenburg", the book of essays "The Imaginary Museum". - Aragon: Interpretation of "Engagement" (novel "Doom Seriously"). - Creativity Selina: the originality of the autobiographical novels "From castle to castle", "North", "Rigaudon". - Creativity of Zhenet: the problem of myth and ritual; drama "High Surveillance" and the novel "Our Lady of Flowers". - "New novel": philosophy, aesthetics, poetics. Robbe-Grillet's work (novels "Elastic Bands", "The Spy",

"Jealousy", "In the labyrinth"), Sarroth ("Planetarium"), Butera ("Distribution of time", "Change"), Simon ("Roads of Flanders", "Georgiki"). - "New criticism" and the concept of "text". Blanchot as a literary theorist and novelist. - French postmodernism: the idea of a "new classic"; Le Clézio's work; the novel "The Forest King" Tournier (peculiarities of poetics, the idea of "inversion"); language experiment of Novarina.

French literature of the second half of the 20th century has largely retained its traditional prestige as a trendsetter in world literary fashion. Its international authority remained deservedly high, even if we take such a conditional criterion as the Nobel Prize. Its laureates were André Gide (1947), François Mauriac (1952), Albert Camus (1957), Saint-Jon Perce (1960), Jean-Paul Sartre (1964), Samuel Beckett (1969), Claude Simon (1985).

It would probably be wrong to equate literary evolution with the movement of history as such. At the same time, it is obvious that the key historical milestones are May 1945 (liberation of France from fascist occupation, victory in World War II), May 1958 (coming to power of President Charles de Gaulle and the relative stabilization of the country's life), May 1968 . ("Student revolution", counterculture movement) - help to understand the direction in which the society was moving. The national drama associated with the surrender and occupation of France, the colonial wars that France waged in Indochina and Algeria, the left movement - all this turned out to be the backdrop for the work of many writers.

During this historical period, General Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970) became a key figure for France. From the first days of the occupation, his voice sounded on the BBC waves from London, calling for resistance to the forces of the Wehrmacht and the authorities of the "new French state" in Vichy, led by Marshal A. -F. Peten. De Gaulle succeeded in transforming the shame of the inglorious surrender into an awareness of the need to fight against the enemy, to give the Resistance movement during the war years the character of a national revival. The program of the National Committee of Resistance (the so-called "charter"), containing in the long term the idea of creating a new liberal democracy, required a profound transformation of society. It was expected that the ideals of social justice shared by the members of the Resistance would be realized in post-war France. To a certain extent, this happened, but it took more than one decade for this. De Gaulle's first post-war government lasted only a few months.

In the Fourth Republic (1946-1958), de Gaulle, as an ideologist of national unity, was largely unclaimed. This was facilitated by the Cold War, which again polarized French society, and the painfully endured process of decolonization (the fall of Tunisia, Morocco, then Algeria). The era of "Great France" came only in 1958, when de Gaulle, who finally became the sovereign president of the Fifth Republic (1958-1968), managed to put an end to the Algerian war, approve the line of France's independent military policy (the country's withdrawal from NATO) and diplomatic neutrality. Relative economic prosperity and industrial modernization led to the formation of the so-called "consumer society" in France in the 1960s.

During the war years, French writers, like their compatriots, were faced with a choice. Some preferred collaboration, one or another degree of recognition of the occupying authorities (Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Robert Brasillac, Louis-Ferdinand Celine), others - emigration (Andre Breton, Benjamin Pere, Georges Bernanos, Saint-Jon Perce, André Gide), others joined to the Resistance movement, in which the Communists played a prominent role. André Malraux under the pseudonym Colonel Berger commanded an armored column, the poet Rene Char fought in the poppies (partisan movement; from the French maquis - bushes) of Provence. Louis Aragon's poetry was quoted by Charles de Gaulle on the radio from London. Leaflets with the poem "Liberty" by Paul Eluard were dropped over French territory by British planes. The common struggle forced the writers to forget about past disagreements: under one cover (for example, the magazine Fontaine, published clandestinely in Algeria), were printed communists, Catholics, democrats - "those who believed in heaven" and "those who did not believe in it" , as Aragon wrote in the poem "Rose and Reseda". The moral authority of the thirty-year-old A. Camus, who became editor-in-chief of the magazine Combat (Combat, 1944-1948), was high. F. Mauriac's journalism temporarily eclipsed his fame as a novelist.

Obviously, in the first post-war decade, literary men who took part in the armed struggle against the Germans came to the fore. The National Committee of Writers, created by the communists headed by Aragon (a staunch Stalinist in those years), compiled "black lists" of "traitors" writers, which caused a wave of protest from many members of the Resistance, in particular Camus and Mauriac. A period of tough confrontation began between the authors of the communist, pro-communist persuasion and the liberal intelligentsia. Typical publications of this time were the communist press against existentialists and surrealists (Literature of the Gravediggers by R. Garaudy, 1948; “Surrealism Against Revolution” by R. Vaillant, 1948).

In journals, politics and philosophy prevailed over literature. This is noticeable in the personalist "Esprit" (Ed. E. Mounier), the existentialist "Tan modern" (Ed. J. -P. Sartre), the communist "Lettre française" (Les Lettres françaises , chief ed. L. Aragon), the philosophical and sociological "Critique" (Critique, chief ed. J. Bataille). The most authoritative pre-war literary magazine, La Nouvelle revue française, ceased to exist for some time.

The artistic merits of literary works seemed to be relegated to the background: the writer was expected, first of all, to be moral; political, philosophical judgments. Hence the concept of engaged literature (litterature engagee, from the French engagement - commitment, recruiting as a volunteer, political and ideological position), citizenship of literature.

In a series of articles in the magazine Comba, Albert Camus (1913-1960) argued that the duty of a writer is to be a full participant in History, to tirelessly remind politicians of conscience, protesting against any injustice. Accordingly, in the novel The Plague (1947), he tried to find those moral values that could unite the nation. Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) went "even further": according to his concept of engaged literature, politics and literary creation are inseparable. Literature should become a “social function” in order to “help change society” (“I thought I was giving myself to literature, but I took the tonsure,” he wrote ironically about this).

For the literary situation of the 1950s, the controversy between Sartre and Camus is very indicative, which led to their final break in 1952 after the release of Camus's essay "The Rebellious Man" (L "Homme revoke, 1951). In it Camus formulated his credo:" I rebel , therefore, we exist ", but nevertheless condemned the revolutionary practice, for the sake of the interests of the new state, legalized repression of dissidents. Camus opposed the revolution (which gave birth to Napoleon, Stalin, Hitler) and the metaphysical rebellion (de Sade, Ivan Karamazov, Nietzsche)" ideal rebellion "- a protest against an inappropriate reality, which actually boils down to self-improvement of the individual. Sartre Camus's reproach for passivity and conciliation outlined the boundaries of the political choice of each of these two writers.

Political engagement of Sartre, who set himself the goal of "supplementing" Marxism with existentialism, led him in 1952 to the camp of "Friends of the USSR" and "fellow travelers" of the Communist Party (a series of articles "Communists and the World", "Answer to Albert Camus" in "Tan Modern" for July and October — November 1952). Sartre participates in international congresses in defense of peace, regularly, up to 1966, visits the USSR, where his plays are staged with success. In 1954, he even became vice-president of the France-USSR Friendship Society. The Cold War forces him to make a choice between imperialism and communism in favor of the USSR, just as in the 1930s R. Rolland saw the USSR as a country capable of resisting the Nazis, giving hope for building a new society. Sartre has to make compromises, which he had previously condemned in his play Dirty Hands (1948), while Camus remains an implacable critic of all forms of totalitarianism, including socialist reality, the Stalinist camps that became the property of publicity.

A characteristic feature of the confrontation between the two writers was their attitude to the "Pasternak case" in connection with the award of the Nobel Prize to the author of "Doctor Zhivago" (1958). There is a letter from Camus (1957 Nobel laureate) to Pasternak expressing solidarity. Sartre, on the other hand, having refused the Nobel Prize in 1964 (“a writer should not turn into an official institution”), expressed regret that Pasternak had been given the prize earlier than Sholokhov, and that the only Soviet work awarded such an award was published abroad and prohibited in their country.

The personality and creativity of J.-P. Sartre and A. Camus had a tremendous influence on the intellectual life of France in the 1940s and 1950s. Despite their disagreements, in the minds of readers and critics, they personified French existentialism, which took on the global task of solving the main metaphysical problems of human existence, substantiating the meaning of its existence. The very term "existentialism" was introduced in France by the philosopher Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973) in 1943, and then was taken up by criticism and Sartre (1945). Camus, on the other hand, refused to recognize himself as an existentialist, considering the category of absurdity as the starting point of his philosophy. However, despite this, the philosophical and literary phenomenon of existentialism in France had integrity, which became obvious when it was replaced in the 1960s by another hobby - "structuralism". Historians of French culture speak of these phenomena as defining the intellectual life of France over the thirty post-war years.

The realities of war, occupation, and Resistance pushed existentialist writers to develop the theme of human solidarity. They are busy substantiating the new foundations of humanity - “the hopes of the desperate” (as defined by E. Munier), “being-against-death”. This is how Sartre's programmatic speech "Existentialism is humanism" (L "Existentialisme est un humanisme, 1946), as well as Camus's formula:" The absurd is the metaphysical state of man in the world ", however," we are not interested in this discovery in itself, but its consequences and rules of conduct derived from it. "

Perhaps, one should not overestimate the contribution of French existentialist writers to the development of the philosophical ideas of the "philosophy of existence" proper, which has deep traditions in German (E. Husserl, M. Heidegger, K. Jaspers) and Russian (N. A. Berdyaev, L. I Shestov) thoughts. In the history of philosophy, French existentialism does not belong to the first place, but in the history of literature it undoubtedly remains with it. Sartre and Camus, both graduates of philosophy departments, eliminated the gap that existed between philosophy and literature, substantiated a new understanding of literature ("If you want to philosophize, write novels," Camus said). In this regard, Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986), a like-minded person and companion of Sartre's life, quotes in her memoirs the witty words of the philosopher Raymond Aron, addressed to her husband in 1935: “You see, if you are engaged in phenomenology, you can talk about this cocktail [the conversation took place in a cafe] and it will already be philosophy! " The writer recalls that Sartre, upon hearing this, literally turned pale with excitement (The Force of Age, 1960).

The influence of existentialism on the post-war romance went along several lines. An existentialist novel is a novel that solves the problem of human existence in the world and society in a generalized way. His hero is “the whole person who has absorbed all people, he is worth everyone, everyone is worth it” (Sartre). The corresponding plot is rather arbitrary: the hero wanders (literally and figuratively) through the desert of life in search of lost social and natural connections, in search of himself. Longing for genuine being is immanent in man (“you would not have looked for me if you had not already found me,” noted Sartre). The "wandering man" ("homo viator", in the terminology of G. Marcel) experiences a state of anxiety and loneliness, a feeling of "lost" and "uselessness", which can be filled to one degree or another with social and historical content. There must be a “borderline situation” in the novel (the term by K. Jaspers), in which a person is forced to make a moral choice, that is, to become himself. Existentialist writers treat the disease of the century not with aesthetic, but with ethical means: gaining a sense of freedom, affirming a person's responsibility for his fate, the right to choose. Sartre stated that for him the main idea of creativity was the conviction that "the fate of the universe depends on each work of art." He establishes a special relationship between the reader and the writer, interpreting it as a dramatic clash of two freedoms.

Sartre's literary work after the war opens with the tetralogy Roads of Freedom (Les Chemins de la liberté, 1945-1949). The fourth volume of the cycle "Last Chance" (La Derniere Chance, 1959) was never completed, although it was published in excerpts in the magazine "Tan Modern" (under the title "Strange Friendship"). This circumstance can be explained by the political situation in the 1950s. What should be the participation of heroes in History with the beginning of the Cold War? The choice became less obvious than the choice between collaboration and Resistance. "With its incompleteness, Sartre's work reminds of that stage in the development of society when the hero realizes his responsibility to history, but does not have enough strength to make history," said the literary critic M. Zeraffa.

The tragedy of existence and insurmountable ideological contradictions receive from Sartre not only prosaic, but also scenic embodiment (plays “The Flies”, Les Mouches, 1943; “Behind a Closed Door”, Huis cios, 1944; “Respectful Slut”, La putain respectueuse, 1946; The Dead Without Burial, Morts sans sépultures, 1946; Dirty Hands, Les Mains sales, 1948). Plays of the 1950s are marked with the stamp of a tragicomedy: the anatomy of the state machine (primitive anti-communism) becomes the theme of the farce play "Nekrassov" (Nekrassov, 1956), the moral relativism of any activity in the field of History and society is postulated in the drama "The Devil and the Lord God" (Le Diable et le Bon Dieu, 1951).

The play Flies, written by Sartre at the request of director Charles Dulen and staged during the occupation, explains the reasons why Sartre turned to theater. He was attracted not by a passion for the stage, but by the possibility of a direct impact on the audience. An engaged writer, Sartre influenced History, through the mouth of Orestes, calling on his compatriots (the humiliated people of Argos) to resist the invaders.

However, created free, a person may never find freedom, remaining a prisoner of his own fears and insecurities. Fear of freedom and inability to act are characteristic of the protagonist of the drama "Dirty Hands" Hugo. Sartre believes that "existence" (existence) precedes "essence" (essence). Freedom as an a priori sign of a person, at the same time, must be acquired by him in the process of existence. Are there limits to freedom? Responsibility becomes its limit in Sartre's ethics. Therefore, we can talk about the Kantian and Christian essence of existentialist ethics (compare with the well-known words of J.-J. Rousseau: "The freedom of one person ends where the freedom of another begins"). When Jupiter warns Orestes that his discovery of the truth will not bring happiness to the people of Argos, but will only plunge them into even greater despair, Orestes replies that he has no right to deprive the people of despair, since "a person's life begins on the other side of despair." Only after realizing the tragedy of his existence, a person becomes free. Everyone needs their own "trip to the end of the night" for this.

In the play “Behind the Closed Door” (1944), which was initially called “The Others” during the work on it, the three dead (Ine, Estelle and Garsen) are condemned to be forever in each other's company, knowing the meaning of the fact that “hell is others ". Death put a limit to their freedom, "behind a closed door" they have no choice. Each is a judge of the other, each tries to forget about the presence of a neighbor, but even silence “screams in their ears”. The presence of another takes away from a person his face, he begins to see himself through the eyes of another. Knowing that his thoughts, which “tick off like an alarm clock,” can be heard, he becomes a provocateur, not only a puppet, a victim, but also an executioner. In a similar way, Sartre considered the problem of the interaction of “being-for-oneself” (awareness of oneself as a free personality with the project of one's own life) with “being-for-others” (feeling oneself under the gaze of another) in the book “Being and Nothingness” (1943) ...

The plays "Dirty Hands" and "The Recluses of Altona" (Les Séquestrés d "Altona, 1959), separated by a decade, are an interpretation of communism and Nazism. In the play" Dirty Hands "Sartre (who had before his eyes the Soviet experience of building a socialist society) opposed personal morality and revolutionary violence. In one of the states of Central Europe, on the eve of the end of the war, the communists seek to seize power. The country (possibly Hungary) will be occupied by Soviet troops. Opinions of the members of the Communist Party are divided: for the sake of success, to enter into a temporary coalition with other parties or rely on One of the leaders of the party, Höderer, is in favor of a coalition. Opponents of such a step decide to eliminate the opportunist and entrust this to Hugo, who becomes Höderer's secretary (Sartre played here the circumstances of Trotsky's murder.) After many hesitation, Hugo commits a murder, but also he himself perishes as an unnecessary witness, he is ready to accept death.

The play is structured in the form of Hugo's reflections on what happened - he is waiting for his comrades, who must declare him useful. Hugo's reasoning about morality Hoederer calls bourgeois anarchism. He is guided by the principle that “clean hands are with those who do nothing” (compare with the revolutionary formula of L. Saint-Just: “You cannot rule innocently”). Although Sartre stated that "Hugo was never sympathetic to him" and he himself considers Höderer's position more "healthy", in fact the play became a denunciation of the bloody Stalinist terror (foreign activities of Soviet intelligence), and this is how it was perceived by the audience and critics.

The play "The Recluses of Altona" is one of the most complex and profound plays by Sartre. In it, Sartre tried to portray the tragedy of the 20th century as a century of historical catastrophes. Is it possible to demand personal responsibility from a person in the era of collective crimes, what were the world wars and totalitarian regimes? In other words, Sartre translates F. Kafka's question “can a person be considered guilty in general” into the historical plane. Former Nazi Franz von Gerlach is trying to accept his age with all its crimes "with the stubbornness of a vanquished". Fifteen years after the end of the war, he spent in seclusion, haunted by terrible memories of the war years, which he lived out in endless monologues.

Commenting on the play Behind a Closed Door, Sartre wrote: “Whatever the circle of hell we live in, I think we are free to destroy it. If people do not destroy it, then they remain in it voluntarily. So they voluntarily imprison themselves in hell. " Franz's hell is his past and present, since history cannot be reversed. No matter how much the Nuremberg court would talk about collective responsibility for crimes, everyone - according to Sartre's logic, simultaneously an executioner and a victim - will experience them in their own way. Franz's hell is not others, but himself: "One plus one equals one." The only way to destroy this hell is by self-destruction. Franz puts himself on the brink of insanity, and then resorts to the most radical way of self-justification - kills himself. In his final monologue, recorded on tape before his suicide, he says the following about the burden of his choice: “I carried this century on my shoulders and said: I will answer for it. Today and forever. " Trying to justify his existence in the face of future generations, Franz claims that he is a child of the 20th century and, therefore, has no right to condemn anyone (including the father; the theme of fatherhood and sonship is also one of the central ones in the play).

"The Recluses of Altona" clearly demonstrate Sartre's disillusionment with engaged literature, with a rigid division of people into guilty and innocent.

A. Camus worked no less intensely than Sartre after the war. The poetics of his "The Stranger" (1942) makes it clear why he was not ready to call himself an existentialist. The seeming cynicism of the narrative has a double orientation: on the one hand, it evokes a feeling of the absurdity of earthly existence, but, on the other hand, behind this manner of Meursault lies an innocent acceptance of every moment (the author brings Meursault to this philosophy before execution), capable of filling life with joy and even justifying human destiny. “Can we give physical life a moral foundation?” Asks Camus. And he himself is trying to answer this question: a person has natural virtues that do not depend on upbringing and culture (and which social institutions only distort), such as masculinity, patronage of the weak, in particular women, sincerity, aversion to lies, a sense of independence , love of freedom.

If existence has no meaning, and life is the only good, why risk it? Reasoning on this topic led the writer Jean Gionot (1895-1970) in 1942 to the idea that it is better to be "a living German than a dead French." Giono's telegram to French President E. Daladier is known about the conclusion of the Munich Agreement (September 1938), which postponed the outbreak of World War II: "I am not ashamed of peace, whatever its conditions." Camus's thought moved in a different direction, as follows from the essay "The Myth of Sisyphe" (Le Mythe de Sisyphe, 1942). "Is life worth the labor to be lived" if "a sense of absurdity can strike a person in the face at the bend of any street"? In the essay, Camus tackles "the only really serious philosophical problem" - the problem of suicide. Contrary to the absurdity of being, he builds his concept of morality on a rational and positive vision of a person who is able to bring order to the initial chaos of life, to organize it in accordance with his own attitudes. Sisyphus, the son of the wind god Aeolus, for his resourcefulness and cunning was punished by the gods and condemned to roll a huge stone onto a steep mountain. But at the very top of the mountain, each time a stone breaks down, and the "useless worker of the underworld" again takes up his hard work. Sisyphus "teaches the highest fidelity, which denies the gods and raises the debris of the rocks." Every moment Sisyphus rises in spirit above his destiny. "We must imagine Sisyphus happy" - this is Camus's conclusion.

In 1947, Camus publishes the novel "The Plague" (La Peste), which was a resounding success. Like Sartre's Roads of Freedom, he expresses a new understanding of humanism as a personality's resistance to the catastrophes of history: ... the way out is not in banal disappointment, but in an even more stubborn striving "to overcome historical determinism, in the" fever of unity "with others. Camus describes an imaginary plague epidemic in the city of Oran. The allegory is transparent: fascism spread like a plague across Europe. Each hero goes his own way to become a fighter against the plague. Dr. Riyo, expressing the position of the author himself, sets an example of generosity and dedication. Another character, Tarru, the son of a wealthy prosecutor, on the basis of his life experience and as a result of the search for "holiness without God" comes to the decision "in all cases to take the side of the victims in order to somehow limit the scope of the disaster." Epicurean journalist Rambert, seeking to leave the city, eventually stays in Oran, admitting that "it is a shame to be happy alone." Camus's laconic and clear style does not betray him this time either. The narration is emphatically impersonal: only towards the end does the reader realize that it is being led by Dr. Riyo, stoically, like Sisyphus, doing his duty and convinced that “a microbe is natural, and the rest is health, honesty, the result of will. "

In his last interview with Camus, when asked whether he himself could be considered an "outsider" (according to the vision of the world as universal suffering), he replied that he was originally an outsider, but his will and thought allowed him to overcome his destiny and made his existence inseparable from time in which he lives.

Theater Camus (the writer was engaged in drama at the same time as Sartre) has four plays: "Misunderstanding" (Le Malentendu, 1944), "Caligula" (Caligula, 1945), "State of Siege" (L "État de siège, 1948)," The Just " (Les Justes, 1949) Particularly interesting is the last play based on the book "Memories of a Terrorist" by B. Savinkov. combined with the assertion of the right to kill (he later analyzes this situation in the essay "The Rebellious Man"). The basis of terrorists' morality is their willingness to give their lives in exchange for the one taken from another. Only if this condition is met, individual terror is justified by them. otherwise, any political murder becomes “meanness.” “They start with a thirst for justice, and end up being in charge of the police,” brings this thought to its logical conclusion Head of the Police Department Skuratov. The planned and then carried out murder of the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich is accompanied by a dispute between the revolutionaries about the price of the revolution and its victims. The bomber Kaliayev violated the order of the Organization and did not throw a bomb into the carriage of the Grand Duke, since there were children in it. Kaliayev wants to be not a murderer, but a "creator of justice", because if children suffer, the people "will hate the revolution." However, not all revolutionaries think so. Stepan Fedorov is convinced that a revolutionary has "all rights", including the right to "step over death." He believes that "honor is a luxury that only carriage owners can afford." Paradoxically, the love for which terrorists act is also an unaffordable luxury. The heroine of the play Dora, who loves the "noble" terrorist Kaliayev, formulated this contradiction: "If the only way out is death, we are not on the right path ... First love, and then justice." Love for justice is incompatible with love for people, this is Camus's conclusion. The inhumanity of the coming revolutions is already embedded in this antinomy.

Camus considers illusory any hope that the revolution can become a way out of the situation that caused it. It was natural in this connection that Camus turned to the experience of FM Dostoevsky. In addition to the original plays, Camus wrote a stage version of the novel Demons (1959). In Dostoevsky, highly esteemed by him, the writer admired the ability to recognize nihilism in a variety of guises and find ways to overcome it. Camus's "Just" is one of the best examples of the theater of "borderline situations" so fruitful in the 1950s.

Camus's latest novel, The Fall (La Chute, 1956), is undoubtedly his most enigmatic work. It is deeply personal in nature, and probably owes its appearance to the author's polemic with Sartre about the essay "The Rebellious Man" (1951). In a dispute with the left-wing intelligentsia, who "caught" Camus of being good-hearted, he brought out in "The Fall" the "false prophet, of whom there are so many today," a person seized with a passion for blaming others (exposing his age) and self-accusation. However, Clamance (his name is taken from the expression "vox clamans in deserto" - "a voice crying in the wilderness") is perceived, according to the writer's biographers, rather as a kind of double of Camus himself than as a caricature of Sartre. At the same time, he resembles Rameau's nephew from the eponymous work of D. Diderot and the hero of "Notes from the Underground" by FM Dostoevsky. In The Fall, Camus masterfully used theatrical technique (the hero's monologue and implicit dialogue), turning his hero into a tragic actor.

One of the variants of the existentialist novel was the personalist novel, the samples of which are quite few, since around the main theorist of this philosophical trend, E. Mounier, were united mainly philosophers and critics, and not writers. The exception is Jean Cayrol (p. 1911). Sartre, I think, not without reason, noted that "in the life of every person there is a unique drama", which is the essence of his life. The drama experienced by Keyrol, a member of the Resistance, a prisoner of the Mauthausen concentration camp, had a dimension that makes it possible to recall the Old Testament Job. The writer tried to answer the questions generated by his life experience: “The prisoner returned, although he seemed doomed. Why did he come back? Why exactly did he come back? What is the meaning of the death of others? "

The answer to these questions was the trilogy "I will live by the love of others" (Je vivrai l "amour des autres, 1947-1950. , 1947) were awarded the Renaudot Prize (1947) and brought the writer wide fame. The novel "They Speak With You" is written in the first person and is a monologue of an unnamed character. exclusivity), since from the experience of the war, I learned that “an ordinary person is the most extraordinary.” From the confusing confession of the narrator, we learn about some facts of his childhood, youth, imprisonment in a concentration camp, about the details of his present life, passing in search of work and in the eternal fear of losing a roof over his head - in a word, about his inner life, woven of memories and reflections.

The plot of the novel is the narrator's wanderings around the city. Meeting people on the streets, talking with neighbors in the apartment in which he is renting a corner - this is the outer outline of the novel. At the same time, due to the evangelical reminiscences, Keyrol gives the character's subjective experiences an almost cosmic scale: he is not only the “first comer”, but represents the entire human race.

"My life is an open door" - this is the principle of the existence of the character of Carol. Here he meets his former fellow prisoner Robert, who makes his living by enlarging photos, and takes him under the protection of the reader in front of the reader: “Keep in mind, if you come across a guy who offers to enlarge photos, do not refuse him. He needs it not in order to survive, but to believe that he is living. " The willingness to sympathize with a person is what, according to the writer, makes a person a person, and a similar quality is inherent in his hero.

Carol's hero solves the problem of choosing a path in life not in favor of society. To join the life of society for him means betraying himself, losing his human dignity: "The harness does not talk, and they do not talk to it." The episode when the hero finds a hundred-franc ticket on the pavement is symbolic. With his beggarly existence, the banknote seems to him a pass to a new life, but “Imagine, I never spent that money; never ... Maybe the day will come when I will cease to be afraid to become one of you ... I do not want to eat, my hunger is too great. " What looks unlikely in terms of events is full of meaning in terms of the philosophy of an act. The values offered to the hero by the surrounding society (personal and material success) are not genuine in his eyes. What is he longing for? “He's in search of a life that is Life,” says Keyrol of his narrator in the preface. Keyrole's hero lives an intense spiritual life, looking for a high meaning in everyday life.

“We are being burned by a fire not kindled by us” - such a spiritual anxiety eats away the protagonists F. Mauriac and J. Bernanos, they refuse to accept the world as it is. The novel offers two ways of confronting an improper world order and loyalty to the ideals of humanity and compassion. On the one hand, this is creativity. Keyrole's hero dreams of writing "a novel in which loneliness explodes like the sun." On the other hand, it is suffering. It regenerates a person, compels him to do great, and not only aesthetic, inner work. Thus, the author is looking for the possibility of true self-fulfillment of the individual, which corresponds to the personalist concept of a “reborn person”. (Compare: "A work of art involves a person in a" productive imagination "; an artist, competing with the world and surpassing it, imparts new values to individuals, makes a person seem to be reborn - this is the most important - the demiurgic aspect of artistic creation, E. Mounier. )

The very title of the trilogy: "I will live by the love of others", clearly opposes the thesis of J.-P. Sartre that “hell is others” (1944). Keyrol insists on an "open position" in relation to the "other", as was characteristic of E. Mounier's personalism, who assimilated the range of topics and problems discussed in non-religious philosophies, primarily in existentialism and Marxism. However, the ways of overcoming the crisis were supposed to be fundamentally different. They are based on the preaching of moral self-improvement, education of others by personal example of "openness" to people, denial of "irresponsibility and selfishness", individualism.

An important document in the creative biography of Carol is the essay "Lazare among us" (Lazare parminous, 1950). The story of the resurrection of Lazarus (Gospel of John, ch. 12) is linked by the author with his own experience of "resurrection from the dead." Thinking about why he was able to survive in the inhuman conditions of the concentration camp, Keyrol comes to the conviction that this can only be explained by the invulnerability of the human soul, its diverse and endless ability for creativity, for imagination, which he calls "the supernatural protection of man."

From an existentialist point of view, the existence of concentration camps was an argument in favor of recognizing the absurdity of the world, as evidenced by David Rousset (1912-1919). Returning from his imprisonment in a concentration camp, Rousse published two essays: "The Concentration World" (L "Univers concentrationnaire, 1946) and" Days of Our Death "(Les Jours de notre mort, 1947), in which he attempted a philosophical analysis of the" world of concentration camps. " , introduced into the post-war French literature the concept of "concentration", "concentration everyday life", seeing in the events of the Second World War confirmation of the absurdity of history.

Keyrol objected to Rousse. The absurd is not omnipotent as long as a person exists: "He fights and needs help." Therefore, the writer was looking for a fulcrum for this struggle, taking as a basis the thesis of a person's focus on proper being, on the "additional development" of reality, which "does not close in itself, but finds its completion outside of itself, in truth." Longing for “being of a“ higher order ”reveals the features of the romantic worldview inherent in Carroll and personalism in general:“ Our immediate future is to feel the concentration camp in our souls. There is no concentration myth, there is a concentration everyday life. It seems to me that the time has come to witness these strange impulses of the Concentrationate, his still timid penetration into the world, born of great fear, his stigmata on us. Art born directly from human convulsion, from catastrophe, should have been called "Lazarev's" art. It is already taking shape in our literary history. "

Existentialist writers did not create a new type of discourse and used traditional varieties of the novel, essay, and drama. They did not create a literary group either, remaining some kind of "loners" in search of solidarity (solitaire et solidaire - the key words in their worldview): "Loners! you will say contemptuously. Maybe so, now. But how lonely you will be without these loners ”(A. Camus).

In the 1960s, with the death of A. Camus, the final stage in the evolution of existentialism begins - the summing up. The "Memoirs" of Simone de Beauvoir ("Memoirs of a well-bred girl", Mémoires d "une jeune filie rangée, 1958;" The force of age ", La Force de Gâge, 1960;" The power of things ", La Force des choses, 1963) are very popular , Sartre's autobiographical novel "Words" (Les Mots, 1964). Assessing his work, Sartre notes: "I have long mistook the pen for the sword, now I am convinced of our powerlessness. It does not matter: I write, I will write books; they are needed, they are still useful. Culture does not save anyone or anything, and it does not justify. But it is the creation of man: he projects himself into it, recognizes himself in it; only in this critical mirror does he see his appearance. "

In the last years of his life, Sartre was more involved in politics than literature. He ran extreme left-wing newspapers and magazines such as JTa Cause du peuple (La Cause du peuple), Libération (Liberation), supporting all protest movements against the existing government, and rejecting the alliance with the communists, who by this time had become its ideological opponents. Struck with blindness in 1974, Sartre died in the spring of 1980 (see the reminiscences of the last years of Sartre's life in Simone de Beauvoir's book The Farewell Ceremony, La cérémonie des adieux, 1981).

The work of A. Malraux (André Malraux,

1901 - 1976). André Malraux is a man-legend, the author of the novels “The Royal Road” (La Voie royale, 1930), “The Lot of Man” (La Condition humaine, 1933), “Hope” (L "Espoir, 1937), which thundered before the war. Resistance in the south of the country, Colonel Maki, commander of the Alsace-Lorraine brigade, Malraux was repeatedly wounded and taken prisoner. In 1945 he met de Gaulle and from that moment remained his loyal companion until the end of his life. In the first post-war government became minister of information, four years later - general secretary of the De Gaulle party, in 1958 - minister of culture.

Although after 1945 Malraux no longer publishes novels, he continues to be active in literary activity (essays, memoirs). In part, his life attitudes are changing: an independent supporter of socialism in the 1930s, after the war he is fighting against Stalin's totalitarianism; formerly a committed internationalist, he now places all his hopes on the nation.

Malraux presented his last novel, Les Noyersde l "Altenburg, Swiss edition - 1943, French edition 1948, as the first part of the novel" Battle with the Angel ", which was destroyed by the Nazis (the author found it impossible to write it again). It lacks the unity of place and time, characteristic of Malraux's previous works, there are features of different genres: autobiography, philosophical dialogue, political novel, military prose.The novel deals with three generations of the respectable Alsatian Berger family (under this pseudonym Malraux himself fought). The narrator's grandfather Dietrich and his brother Walter, friends of Nietzsche, on the eve of 1914 organize philosophical colloquia at the Altenburg monastery, in which famous German scientists and writers participate, solving the question of the transcendence of man (the prototype of these colloquia was Malraux's conversations with A. Gide and R. Martin du Gard in the Abbey of Pontilly, where European intellectuals met in the 1930s.) The narrator's father Vincent Berger, a participant in the 1914 war, experienced the horror of the first use of chemical weapons on the Russian front. The narrator himself begins his story with a recollection of a camp of French prisoners (among whom he was) in Chartres Cathedral in June 1940 and ends the book with an episode of a military campaign of the same year, when he, commanding a tank crew, found himself in an anti-tank ditch under the crossfire of the enemy and miraculously survived: “Now I know what the ancient myths about heroes who returned from the kingdom of the dead mean. I hardly remember the horror; I carry the solution to a mystery, simple and sacred. This is probably how God looked at the first man. "

New horizons of Malraux's thought are outlined in The Hazel Trees of Altenburg. Heroic action - the core of his first novels - fades into the background. It is still about how to overcome anxiety and conquer death. But now Malraux sees victory over fate in artistic creation.

One of the most striking episodes of the novel is symbolic, when Friedrich Nietzsche, who has fallen into madness, is being taken home to Germany by friends. In the Saint Gotthard tunnel, in the darkness of a third-class carriage, Nietzsche's singing is suddenly heard. This singing of a man struck by madness transformed everything around. The carriage was the same, but in its darkness the starry sky shone: “It was life - I say simply: life ... millions of years of the starry sky seemed to me swept away by man, as our poor destinies sweep away the starry sky”. Walter adds: “The greatest mystery is not that we are left to chance in the world of matter and stars, but that in this prison we are able to take out images powerful enough to disagree with the fact that we are nothing "(" Pieg notre néant ").

All of Malraux's post-war work - books of essays "Psychology de l" art, 1947-1949), "Voices of Silence" (Les Voix du silence, 1951), "Imaginary Museum of World Sculpture" (Le Musée imaginaire de la sculpture mondiale , 1952-1954), "Metamorphoses of the Gods" (La Metamorphose des dieux, 1957-1976) - devoted to reflections on art as "anti-destiny".

Following O. Spengler, Malraux is looking for features of similarity between extinct and modern civilizations in a single space of culture and art. The world of art created by man is not limited to the real world. He “devalues reality, as Christians and any other religion devalue it, devalue by their belief in privilege, the hope that man, and not chaos, carries within himself the source of eternity” (“Voices of Silence”). An interesting remark by the critic C. Roy: “An art theorist, Malraux does not describe works of art in their diversity: he tries to collect them, merge them into one permanent work, into the eternal present, a constantly renewed attempt to escape the nightmare of history.<...>At 23 in archeology, at 32 in the revolution, at 50 in the historiography of art, Malraux seeks religion. "

1967 Malraux published the first volume of Antimémoires. In them, in accordance with the name, there are no recollections of the writer's childhood, there is no story about his personal life ("is it important what is important only for me?"), There is no recreation of the facts of his own biography. It is mainly about the last twenty-five years of his life. Malraux starts from the end. Reality is intertwined with fiction, the characters of his early novels come to life in unexpected contexts, the leaders of nations (de Gaulle, Nehru, Mao Zedong) become heroes of the narrative. Heroic destinies triumph over death and time. Compositionally, "Anti-memoirs" are formed around several dialogues that Malraux conducted with General de Gaulle, Nehru and Mao. Malraux takes them beyond the framework of his era, places them in a kind of eternity. He opposes the destructive nature of time to the heroism of the Promethean principle - the actions of a person "identical to the myth about him" (Malraux's statement about de Gaulle, applied to himself).

In the 1960s, new trends in philosophy, the humanities, and literature were heading in the opposite direction to the concerns of the existentialists. A writer who tries to solve all the problems of culture and history evokes both respect and mistrust. It is especially characteristic of structuralists. J. Lacan begins to talk about “decentering the subject”, K. Levi-Strauss argues that “the goal of the humanities is not the constitution of a person, but his dissolution”, M. Foucault expresses the opinion that a person can “disappear like a drawing in the sand, washed away by the coastal wave.

Philosophy moves away from existential themes and deals with the structuring of knowledge, the construction of systems. Accordingly, the new literature addresses the problems of language and speech, neglects philosophical and moral problems. The creativity of S. Beckett and his interpretation of the absurd as nonsense is becoming more relevant.

In the 1970s, it can be stated that existentialism has completely lost its leading positions, but one should not underestimate its deep indirect influence on modern literature. Perhaps Beckett goes further in the development of the concept of absurdity than Camus, and Jean Genet's theater surpasses Sartre's drama. It is obvious, however, that without Camus and Sartre there would be no Beckett or Genet. The influence of French existentialism on post-war French literature is comparable to that of surrealism after World War I. Each new generation of writers, up to the present time, has developed its own attitude towards existentialism, towards the problem of engagement.

Louis Aragon (Louis Aragon, nast, name - Louis Andrieux, Louis Andrieux, 1897-1982), like Malraux, Sartre, Camus, is one of the engaged writers. This resulted in his commitment to communist ideas. If A. Gide became interested in communism by reading the Gospel, then Aragon was captured by the idea of social revolution, to which he came from the idea of revolution in art, being one of the founders of surrealism. It took him ten years of artistic experimentation in the circles of the "golden youth" to then master the method he called "socialist realism" and to recreate the era of the 1920s and 1930s in the novels of the cycle "The Real World" ("Basel Bells", Les Cloches de Bâle, 1934; "Rich Quarters", Les Beaux quartiers, 1936; "Passengers of the Imperial", Les Voyageurs de l "іmregialе, 1939, 1947;" Aurelien ", Aurélien, 1944) and" Communists "(Les Communistes, 1949-1951, 2nd ed. 1967-1968).

An active member of the Resistance, a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of France, Aragon on the pages of the Lettre Française newspaper tried, although not always consistently (carried away by the works of Yu. Tynyanov, V. Khlebnikov, B. Pasternak), to pursue the party line in art. But after the XX Congress of the CPSU, he is revising his previous political views. In the novel "Holy Week" (La Semaine sainte, 1958), he implicitly draws a parallel between the tumultuous times of the Napoleonic hundred days and the debunking of the Stalinist cult of personality. The core of the novel turns out to be the betrayal of Napoleon's officers (and, accordingly, the communists - Stalin) and their sense of guilt. In the novel “Doom Seriously” (La Mise à mort, 1965), of particular interest are the description of the funeral of A.M. an eyewitness to events that at first did not seem to be anything particularly significant. And when later I comprehended their meaning, I felt like a simpleton: after all, seeing and not understanding is the same as not seeing at all.<...>All I saw was the luxurious marbled and sculptured metro stations. So talk about realism after that. The facts are striking, and you turn away from them with beautiful-minded judgments ... Such an awkward thing life. And we all try to find meaning in it. We are all trying ... Naive people. Can you trust the artist? Artists go astray, are mistaken: "he is either a satellite or a criminal."

“We use books as mirrors in which we try to find our reflection,” writes Aragon in the afterword to the novel. The hero's double, Antoan, is the Aragon-Stalinist, whom the writer himself wants to kill in himself ("death seriously"). He seems to be able to take such a step with impunity ("Goethe was not accused of murdering Werther, and Stendhal was not prosecuted because of Julien Sorel. If I kill Antoan, at least there will be extenuating circumstances ..."). But it turns out that Antoan the Stalinist cannot be killed. Firstly, because he is “long dead”, and secondly, because “I would have to go to meetings instead of him”. In a word, the past lives in us, it is not so easy to bury it.

The events of Prague in 1968 reconciled Aragon with its own falling away from Soviet-style communism. He ceases to worry about how to match his role as an orthodox party member - speaks in defense of A. Solzhenitsyn, A. Sinyavsky, Y. Daniel, petitions the Soviet government to release film director S. Parajanov from prison. His newspaper, Lettre Française, was closed in the early 1970s.

The problem of engagement appears in a completely different way in the work of Louis-Ferdinand Céline (crust, name - Louis-Ferdinand Destouches, 1894-1961). "This is a person who has no significance in the team, he is just an individual" - these words of Celine (play "Church", 1933), which served as an epigraph to Sartre's Nausea, are applicable to Celine himself, who refused to recognize the responsibility of a person to society.

The posthumous fate of this writer is no less surprising than his life: according to critics, none of the French writers of the 20th century currently has a more lasting literary status than him. His "black lyricism", accompanied by deconstruction-reconstruction of the syntax of the French language, is an artistic achievement comparable in importance with the sonnets of S. Mallarmé and the prose of M. Proust. In addition to the artistic merit of the style, many French writers of the 20th century (including Sartre and Camus) were influenced by the general intonation of Celine's works. “The relationship between Sartre and Celine is striking. Obviously, Nausea (1938) follows directly from Journey to the End of the Night (1932) and Death on Credit (1936). The same irritation, prejudice, desire to see the ugly, absurd, disgusting everywhere. It is noteworthy that the two greatest French novelists of the 20th century, no matter how far from each other, are united in their disgust for life, hatred for existence. In this sense, Proust's asthma - an allergy that has taken on the character of a common disease - and Celine's anti-Semitism are similar, served as a crystal basis for two different forms of rejection of the world, "writes postmodernist writer M. Tournier about Celine.

During the First World War, Celine was mobilized and at the age of twenty ended up at the front, was wounded in the arm. For Selin, participation in the war became that very unique drama that determined his future life. A doctor by training, he had all the prerequisites to make a career: in 1924 he brilliantly defended his dissertation, made reports at the Academy of Sciences, went on business trips to North America, Africa and Europe, and in 1927 opened a private practice. However, the sphere of his true interests turned out to be different. Without breaking completely with the profession of a doctor, Celine begins to write and immediately becomes famous: his first novels Voyage au bout de la nuit (Renaudot Prize 1932) and Death on Credit (Mort à crédit, 1936) produced the effect of a bomb exploding. The sympathetic content of the novels was enhanced by their extraordinary stylistic originality.

The material for "Traveling ..." was the writer's life experience: memories of the war, knowledge of colonial Africa, trips to the United States, which had been booming in the first third of the century with the triumph of industrial capitalism, as well as medical practice in a poor suburb of Paris. The picaresque hero of the novel, Bardamu, tells his story in the first person, drawing before the reader a ruthless panorama of the absurdity of life. The ideology of this antihero is provocative, but his language is even more provocative. S. de Beauvoir recalled: “We knew many passages from this book by heart. His anarchism seemed to us akin to ours. He attacked war, colonialism, mediocrity, common places, society in a style and tone that captivated us. Celine has cast a new tool: writing is as lively as speaking. What pleasure we got from him after the frozen phrases of Gide, Alain, Valerie! Sartre grasped its essence; he finally abandoned the prim language that he had used until now. "

However, Celine's pre-war anti-Semitic pamphlets and demonstrative collaboration (“To become a collaborator, I did not wait for the Commandant's Office to fly its flag over the Crillon Hotel”) during World War II caused his name to almost disappear from the literary horizon, although in 1940s - j950s he wrote and published a novel about his stay in London in 1915, "Puppets" (Guignol's Band, 1944), the story "Trench" (Casse-pipe, 1949), as well as notes about the bombing 1944 and stay in a political prison "Extravaganza for another occasion" (Féerie pour une autre fois, 1952) and continued their essay "Normans" (Normance, 1954).

In 1944, after the collapse of the Vichy government, Celine fled to Germany, then to Denmark. The Resistance Movement sentenced him to death. Sartre wrote that Celine was “bought” by the Nazis (Portrait of an Anti-Semite, 1945). Denmark refused to extradite him, nevertheless, in Copenhagen, the writer was put on trial and sentenced to fourteen months in prison, living under police supervision. In 1950, Celine was amnestied, he was given the opportunity to return to France, which he did in 1951.

In France, Celine works a lot and begins to publish again, although it was difficult for him to expect an unbiased attitude towards himself and his work. Only after the death of Selin did his rebirth begin as a major writer who blazed new paths in literature. For literary France at the end of the 20th century, he turned out to be the same iconic figure as J. Joyce for England and U Faulkner for the United States.

Celine explained his creative intention solely as an attempt to convey an individual emotion that must be overcome. The prophetism inherent in his works testifies to the fact that the writer gave dark pleasure to the role of Cassandra: one against all.

The autobiographical chronicles "From castle to castle" (D "un château l" autre, 1957), "North" (Nord, 1960) and the posthumously published novel "Rigodon" (Rigodon, 1969) describe Selina's apocalyptic journey accompanied by his wife Lily, a cat Beber and actor friend Le Vigan in Europe on fire. Selin's path first lay in Germany, where at Sigmaringen Castle he joined the agonizing Vichy government in exile and worked as a doctor for several months, treating collaborators. Then, having secured permission to leave through friends, Celine, under the bombs of allied aviation, managed to reach Denmark on the last train. Explaining his intention to depict the dying days of the Pétain government, Celine wrote: “I am talking about Pétain, Laval, Sigmaringen, this is a moment in the history of France, like it or not; maybe sad, you can regret him, but this is a moment in the history of France, he took place and someday they will talk about him at school. " These words of Selina require, if not sympathy, then understanding. In the face of complete military defeat, the government of Marshal Petain (national hero of the First World War) managed to achieve the division of the country into two zones, as a result of which many of those who wanted to leave France were able to do so through the south of the country.

The "lace" style of the trilogy, written in the first person (like all Selinov's works), conveys a feeling of total chaos and confusion. However, the hero, the prototype of which is the author himself, is obsessed with the desire to survive at all costs, he does not want to admit that he is defeated. The parodic tone of the tragicomic narrative hides a storm of feelings and regrets in his soul.

The seeming ease of Celine's conversational manner is the result of hard and thoughtful work ("five hundred printed pages equals eight thousand handwritten pages"). The writer R. Nimier, a great admirer of Celine's work, characterized him as follows: “The North teaches more a lesson in style than a lesson in morality. Indeed, the author does not provide advice. Instead of attacking the Army, Religion, Family, he constantly talks about very serious things: the death of a person, his fear, his cowardice. "

The trilogy covers the period from July 1944 to March 1945. But the chronology is not consistent: the first should have been the novel "North", and the action of the novel "Rigaudon" unexpectedly for the reader breaks off at the most interesting place. A disjointed narrative that does not fit into the framework of any genre, imbued with nostalgic memories of the past. Finding himself at the crossroads of History, the hero is trying to be aware of what is happening and find an excuse for himself. Celine creates his own myth: he is a great writer ("one might say, the only genius, and it does not matter whether damned or not"), a victim of circumstances. The dance of death and the atmosphere of general madness depicted by Celine work to create the image of an extravagant lone rebel. The question of who is crazier - a misunderstood prophet or the world around him - remains open: “Every person who speaks to me is a dead man in my eyes; dead man in respite, if you like, living by chance and for a moment. Death lives in me. And she makes me laugh! Here's something to remember: my dance of death amuses me like a boundless farce ... Trust me: the world is funny, death is funny; that's why my books are funny and at heart I am cheerful. "

In contrast to the biased literature, the fascination with Celine began in the 1950s. The counterculture movement in 1968 also raised him on the shield as an anti-bourgeois writer and a kind of revolutionary. By the end of the 20th century, Selin's work became, in the works of postmodernist theorists (Y. Kristev), an antithesis of all previous literature.