Satirical devices in the fairy tale selfless hare. Reception of the grotesque in "Fairy Tales" M

Read also

The question is difficult for adolescents 16-30 years old.

Pechorin did not like Bela.

Balkonsky did not like Natasha.

Raskolnikov and Bazarov generally loved only themselves.

Onegin did not like Tatiana one hundred poods.

All of them are heroes of their time - And what is interesting Most modern men are the same in character as they are - our ancestors. They also do not know what they want, who they need. On the other hand, a woman seems to be needed - decent - for life, or so - for fun, so to indulge.

And Pechorin, in these searches, generally became a rapist. He read it recently and was horrified: Stole. He raped. He broke the girl’s life. And he became a hero of that time.

And you ask whether Onegin loved?

My answer is no! I didn’t love. And in my search I recommend - do not ruin the life of naive girls - they are still stupid and dreamy in their youth!

Interest Ask. To think whether a literary character loved another literary character. Let's think about it. I think that Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin told us all the following story: there are men who love what they cannot get. The novel in verse showed such an elite hero - a jaded young man who thinks that he has already understood and comprehended everything in this life. He lived like this, playfully, it was more interesting for him to go to a duel for an unattainable object (Olga) than to respond with sincere feelings to a declaration of love for a good girl.

And then, when Tatiana got married, she suddenly became interesting to him. And I think that precisely because I got into the category of unattainable. And it was only when this girl told him that she would not cheat on her husband because she didn’t have such principles, no matter whom she loved, then he realized who he really lost. At the end of the novel, this young man, who naively believed that he had already learned everything in this life, stands “as if struck by thunder…”;

Did Onegin love Tatiana? I fell in love when everything was already lost. With some men it happens - a storm of sensations when it is no longer needed by anyone.

It is difficult to answer this question unambiguously, because in Pushkin's work there are no bare facts and statements, it would simply not be interesting to read. The reader himself can think out and understand (or not understand) the characters. Personally, my opinion is that I still loved, but love is different, like people themselves. Perhaps this was such a man's love that Onegin did not immediately recognize or did not know what to do with it. Perhaps what he felt was the maximum that he was capable of feeling.

Of course I loved, I just didn't want to get everything so accessible, I wanted to fight in a duel for the inaccessible. And when Tatyana became unavailable, he suddenly decided to confess his love to her, but it was already too late, Tatyana, although she loved him, decided to be faithful to her husband.

I doubt Onegin's love for Tatiana before and after her marriage. Love is such a thing that does not change forever, it is today, the same as yesterday and a hundred years ago. Therefore, Eugene Onegin did not like Tatiana, and after refusal, he saw her dignity in the heroine, what distinguished her from most of her contemporaries. Time would have passed, life with her would have bored Eugene Onegin and he would have left Tatyana. Therefore, it is good that she refused Onegin, she got sick, she almost got rid of him. At least she knew love, but Onegin did not.

Roman Eugene Onegin written by the brilliant Pushkin, it is amazing, but what the poet wrote so long ago is relevant to this day.

Of course he loved, but with some kind of selfish love, even for the sake of love, he did not want to marry, and then when it was already too late only then he fully realized that alone there is no salvation, even if it is very convenient.

They wrote and write that Onegin is an egoist and that it was not love on his part. If there were no love, there would not be this wonderful story. Onegin loved Tatiana. But he loved her in his own way. It now seems that he was a "spoiled man". Then it was in the order of things. And Tatyana was a wise lady and did not want to destroy what had already been created.

I remember writing an essay at school and many agreed that there was love. But so peculiar.

Yes, he loves, because a whole story has been written about this!

And in my opinion he did not like e ... She attracted his attention only when she was already married, unapproachable, respectable lady ... And the letter e did not penetrate him in any way, at that moment she was a girl in love with him - too easy a victory ... Not interesting ...

Love in the understanding of Onegin and Tatiana.

(after A. Pushkin "Eugene Onegin")

In my essay, I want to understand and understand what love means for Onegin and Tatiana. I would like to understand why Eugene and Tatiana did not stay together, and, in general, is it possible.

Eugene Onegin is an extraordinary figure. He is successful in society, popular with the ladies, but, nevertheless, he felt bored and left for the village. In this complex spiritual phenomenon, called Eugene Onegin, there are two main centers. One of them is indifference, coldness, the other center is described in the first chapter "but in what he was a true genius" - and further follows the characterization of Eugene as a "genius of love". At the beginning, it can be mistaken for the irony, grin, Don Juanism of the hero. We see a free, fashionable, passionate rake, an apostate of fashionable pleasures, an enemy and a waste of order.

He sees no sense in anything, is indifferent to everything except self-esteem and independence. The feeling of love is alien to him, only "the science of tender passion" is familiar to him. It is difficult to imagine that in a few years this callous character will comprehend a selfless, spontaneous, poetic feeling. In the meantime, he sees in girls only potential brides planning how to spend his fortune after the wedding. He perceived Olga and Tatiana in the same way. He was surprised to learn that his friend (Lensky) was in love with Olga:

When I was like you, poet

Olga has no life in her features

Exactly in the Madonna of Vendice

She is round, red in face,

Like that stupid moon

In this stupid sky.

He admitted that if he was a poet, he would choose Tatiana. He is not a poet, but he notices the personality, the singularity of the heroine. She attracted his interest with her mystery, elusiveness, spirituality, depth. But he only singled her out of the two sisters, nothing more. The girl did not arouse any other interest in him. But his soul, incapable of deep feelings, was touched by Tatyana's letter:

But, having received Tanya's message,

Onegin was vividly moved:

The language of girlish dreams

In it he revolted the thoughts with a swarm.

After reading the letter, Onegin felt the excitement of his soul, for a long time, and perhaps never, he had never known a real deep feeling that would have worried him so much. “Perhaps an old sense of ardor took possession of him for a minute,” but Eugene returned from the clouds to the ground, overwhelmed his feelings, decided that they did not suit each other, did not dare to try his luck. The hero is endowed with intelligence, therefore he acts rationally, consciously, but love and reason are different things. There are times when you need to "cast aside" the calculation, the head, and live with the heart. Eugene's heart is "chained" and it is very difficult to break them.

After Lensky's death, we do not see the hero, he leaves, and comes back completely different, the opposite. We do not know what happened to the hero during his journey, what he thought, he understood, why he “removed the chains from his heart,” but we see another person who is able to feel and love, experience and suffer. Perhaps he realized that he had done the wrong thing, rejecting Tatyana, that in vain he had decided not to try to live the fabulous, airy life that Lensky admired so much, but nothing can be returned, and the image of Tanya “melts” in Onegin's memory.

His meeting with Tatiana in St. Petersburg was a surprise to him:

"Really, - thinks Eugene: - is she really? .." Both heroes have changed over these 2 years. Tatiana follows Eugene's advice:

"Learn to rule yourself,

not everyone, like me, will understand

inexperience leads to trouble. "

Eugene becomes sensual and vulnerable. He falls in love: he counts the hours before meeting Tanya, seeing her, he is speechless. The hero is overwhelmed with feelings, he is gloomy, awkward, but this does not touch Tatyana's soul:

He's barely awkward

The head answers her

Its full of gloomy thought.

He looks gloomily. She

sitting, calm and free.

In all Eugene's actions, inexperience is visible, he never loved the way he was now. His youth - the time of love - he lived the life of an adult, strict indifferent man. Now that this time has passed, and the time has come for a real adult life, love makes him a boy, inexperienced and insane.

In the anguish of loving thoughts

He spends day and night.

He is happy if he throws it on her

Boa fluffy on the shoulder,

Or touches hotly

Her arms, or spread

Before her is a motley regiment of liveries,

Or he will raise a handkerchief for her.

Onegin enjoys every minute of his life spent next to Tatyana. Does not pay attention to his appearance, painful condition:

Onegin begins to turn pale:

She can't see it, or it's not a pity,

Onegin dries - and barely

He's not sick with consumption.

With each of his actions, Eugene wants to earn attention, Tatiana's tender look, but she is insensitive and cold. She hid all her feelings far, far away, she “bound her heart with chains,” as Onegin once did. Tanya's current life is a masquerade. She has a mask on her face that looks quite natural, but not for Eugene. He saw her as none of the people around her now. He knows a gentle and romantic, naive and in love, sensitive and vulnerable Tanya. The hero hopes that all this could not disappear without a trace, that under this mask the real face of the girl is hidden - the village Tatiana, who grew up on French novels and dreams of great and pure love. For Eugene, all this was very important, but gradually the hope melted away, and the hero decided to leave. On the last explanation with Tatiana, he "looks like a dead man." His passion is similar to Tanya's suffering in Chapter 4. When the young man came to her house, he saw the real Tanya without a mask and pretense:

... Simple maiden

with dreams, with the heart of the old days,

now resurrected in her again.

We all see that the village Tanya is alive, and her behavior is just an image, a cruel role. Now let's move to the village and try to understand what love means for Tanya at the beginning and at the end of the novel.

Tatiana, like Onegin, was a stranger in the family. She did not like noisy games, feasts, never caressed her parents. Tanya lived in another, parallel world, the world of books and dreams.

She liked novels early;

They replaced everything for her:

She fell in love with deceptions

And Richardson and Russo.

from others, deep concentration on the inner movements of the soul make love for Tatyana more imperious. In Onegin, she saw all the best sides of literary heroes, she fell in love with the image created by writers, society and Tatyana herself. She lives a dream, believes in a happy ending to the novel called life. But dreams dissipate when Eugene answers her letter, flirts with Olga, kills a friend. Then Tatiana understands that dreams and reality are different things. The hero of her dreams is far from humanity. The world of books and the world of people cannot exist together, they must be separated. After all these events, Tatyana does not suffer, does not try to forget her lover, she wants to understand him. To do this, the girl visits Eugene's house, in which she learns other, secret sides of Onegin. Only now Tanya begins to understand, comprehend the actions of the hero. But she understood him too late, he left, and it is not known whether they will see each other again. Perhaps the girl would have lived with dreams of meeting, studying his soul, spending time in his house. But an event happened that changed Tanya's life. She was taken to Petersburg, given in marriage, separated from her native nature, books, the country world with the stories and tales of the nanny, with her warmth, naivety, cordiality. All that, with which she was separated, made up the favorite circle of the heroine's life. In St. Petersburg, no one needs her, her provincial views seem strange and naively funny there. Therefore, Tanya decides that the best in this case would be to hide under a mask. She hides her affections, becomes a model of "impeccable taste", a faithful snapshot of nobility, sophistication. But, I am sure that Tanya constantly recalls that serene life, full of hopes and dreams. She remembers her beloved quiet nature, she remembers Eugene. She does not try to "bury" the village Tanya, but simply does not show her to those around her. We see that inwardly Tanya has not changed at all, but now she has a husband, and she cannot recklessly surrender to love.

Reflecting on what love means for Tatiana at the end of the novel (since we already understood that in the beginning love played a big role in the heroine's life), I came to this conclusion. Tanya has remained the same, so sometimes she allows herself to think, dream about another life, full of love and tenderness. But she, who grew up in the spirit of the patriarchal nobility, cannot break the marriage bond, cannot build her happiness on the misfortune of her husband. Therefore, she surrenders to the will of fate, rejects love and lives in a world full of lies and pretense.

At the beginning of the novel, when the characters' happiness seems so close, Onegin rejects Tatiana. Why? Simply because he is not only cruel, but also noble. He understands that happiness will be short-lived and decides to reject Tanya immediately, rather than gradually torment her. He sees the hopelessness of their relationship, so he decides to leave without starting a relationship. At the end of the novel, the situation changes, the hero lives with his love, it means a lot to him. But now the final word is for the heroine. But she also refuses the relationship. Again, why? The girl was brought up according to ancient customs. Cheating on her husband, leaving him is impossible for her. For this act, everyone would condemn her: family, society, and, first of all, herself. We see different characters of heroes, upbringing, worldview, different attitudes towards love. To combine them, you need to change all these qualities, all these data, but then we will not see Eugene Onegin and Tatyana Larina, but completely different heroes, with different qualities. But who can guarantee that these people will be drawn to each other, as our heroes?

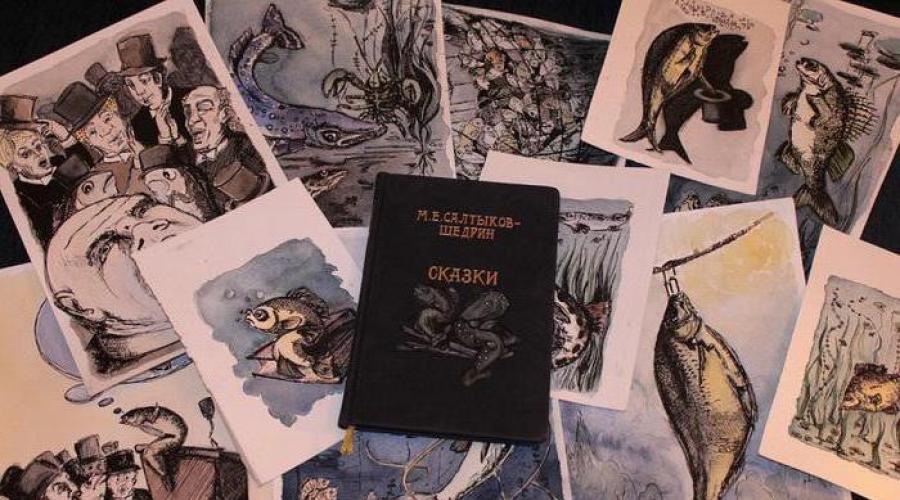

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin is the creator of a special literary genre - a satirical fairy tale. In short stories, the Russian writer denounced bureaucracy, autocracy, liberalism. This article examines such works of Saltykov-Shchedrin, such as "The Wild Landowner", "The Eagle-Patron", "The Wise Gudgeon", "Crucian-idealist".

Features of the tales of Saltykov-Shchedrin

Allegory, grotesque, and hyperbole can be found in the tales of this writer. There are features characteristic of the Aesopian narrative. The communication between the characters reflects the relationships that prevailed in the society of the 19th century. What satirical techniques did the writer use? In order to answer this question, it is necessary to briefly tell about the life of the author, who so mercilessly exposed the inert world of landowners.

about the author

Saltykov-Shchedrin combined literary activity with public service. The future writer was born in the Tver province, but after graduating from the Lyceum he left for St. Petersburg, where he received a position in the War Ministry. Already in the first years of work in the capital, the young official began to languish with bureaucracy, lies, and boredom that reigned in institutions. With great pleasure Saltykov-Shchedrin attended various literary evenings, which were dominated by anti-serfdom sentiments. He informed the people of St. Petersburg about his views in the novellas "Confused Business", "Contradiction". For which he was exiled to Vyatka.

Life in the provinces made it possible for the writer to observe in every detail the bureaucratic world, the life of the landowners and the peasants oppressed by them. This experience became the material for the works written later, as well as the formation of special satirical techniques. One of the contemporaries of Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin once said about him: "He knows Russia like no one else."

Satirical techniques of Saltykov-Shchedrin

His work is quite diverse. But fairy tales are perhaps the most popular among the works of Saltykov-Shchedrin. There are several special satirical techniques with the help of which the writer tried to convey to the readers the inertness and deceit of the landlord's world. And above all, in a veiled form, the author reveals deep political and social problems, expresses his own point of view.

Another technique is the use of fantastic motives. For example, in "The Tale of How One Man Fed Two Generals," they serve as a means of expressing dissatisfaction with the landlords. And finally, when naming Shchedrin's satirical devices, one cannot fail to mention symbolism. After all, the heroes of fairy tales often point to one of the social phenomena of the 19th century. So, the main character of the work "Horse" reflects all the pain of the Russian people, oppressed for centuries. Below is an analysis of individual works of Saltykov-Shchedrin. What satirical techniques are used in them?

"Crucian idealist"

In this tale, the views of the intelligentsia are expressed by Saltykov-Shchedrin. The satirical techniques that can be found in the work "Carp the idealist" are symbolism, the use of folk sayings and proverbs. Each of the heroes is a collective image of representatives of a particular social class.

In the center of the plot of the tale is the discussion between Karas and Ruff. The first, which is already understood from the title of the work, tends to an idealistic worldview, belief in the best. Ruff is, on the contrary, a skeptic, sneering at the theories of his opponent. There is a third character in the tale - Pike. This unsafe fish symbolizes the powerful in the work of Saltykov-Shchedrin. Pikes are known to feed on crucian carp. The latter, driven by the best feelings, goes to the predator. Karas does not believe in the cruel law of nature (or an established hierarchy in society for centuries). He hopes to bring Pike to reason with stories about possible equality, universal happiness, virtue. And therefore dies. Pike, as the author notes, the word "virtue" is not familiar.

Satirical techniques are used here not only to expose the harshness of representatives of certain strata of society. With the help of them, the author tries to convey the futility of the moralistic disputes that were widespread among the intelligentsia of the 19th century.

"Wild landowner"

The theme of serfdom is given a lot of place in the work of Saltykov-Shchedrin. He had something to tell readers about this. However, writing a publicistic article on the relationship of landowners to the peasants or publishing a work of fiction in the genre of realism on this topic was fraught with unpleasant consequences for the writer. Therefore, I had to resort to allegories, light humorous stories. In "Wild Landowner" we are talking about a typical Russian usurper, not distinguished by education and worldly wisdom.

He hates "men" and dreams of limiting them. At the same time, the stupid landowner does not understand that without the peasants he will perish. After all, he does not want to do anything, and he does not know how. One might think that the prototype of the hero of the fairy tale is a certain landowner whom, perhaps, the writer met in real life. But no. We are not talking about any particular gentleman. And about the social stratum as a whole.

In full, without allegories, Saltykov-Shchedrin disclosed this theme in "Gentlemen Golovlevs". The heroes of the novel - representatives of a provincial landowner family - perish one after another. The reason for their death is stupidity, ignorance, laziness. The character of the fairy tale "The Wild Landowner" will face the same fate. After all, he got rid of the peasants, which at first was glad, but now he was not ready for life without them.

"Eagle patron"

The heroes of this tale are eagles and crows. The former symbolize the landlords. The second are peasants. The writer again resorts to the method of allegory, with the help of which he makes fun of the vices of the powerful. The tale also includes the Nightingale, Magpie, Owl and Woodpecker. Each of the birds is an allegory for a type of people or social class. The characters in the "Eagle the patron" are more human than, for example, the heroes of the fairy tale "Carp the idealist". So, the Woodpecker, who has a habit of reasoning, at the end of the bird's story does not become a victim of a predator, but ends up behind bars.

"Wise gudgeon"

As in the works described above, in this tale the author raises questions that are relevant for that time. And here it becomes clear from the very first lines. But the satirical techniques of Saltykov-Shchedrin are the use of artistic means to critically portray not only social vices, but also universal ones. The narration in "The Wise Gudgeon" is conducted by the author in a typical fairytale style: "Once upon a time ...". The author is characterized as follows: “enlightened, moderately liberal”.

Cowardice and passivity are ridiculed in this tale by the great master of satire. After all, it was precisely these vices that were characteristic of the majority of the intelligentsia in the eighties of the XIX century. The gudgeon never leaves his refuge. He lives a long life, avoiding encounters with dangerous inhabitants of the aquatic world. But only before his death he realizes how much he missed in his long and worthless life.

Grotesque is a term that means a type of artistic imagery (image, style, genre) based on fantasy, laughter, hyperbole, bizarre combination and contrast of something with something. In the genre of the grotesque, the ideological and artistic features of Shchedrin's satire were most clearly manifested: its political acuteness and purposefulness, the realism of its fantasy, the ruthlessness and depth of the grotesque, the crafty sparkling humor.

Shchedrin's “Tales” in miniature contain the problems and images of the entire work of the great satirist. If, except for "Tales", Shchedrin wrote nothing, then they alone would have given him the right to immortality. Of the thirty-two tales of Shchedrin, twenty-nine were drunk by him in the last decade of his life (most from 1882 to 1886), and only three tales were created in 1869. Fairy tales, as it were, sum up the forty years of the writer's creative activity. Shchedrin often resorted to the fabulous genre in his work. Elements of fairy-tale fantasy are also present in The History of a City, while the satirical novel Modern Idyll and the chronicle Abroad include completed fairy tales.

And it is no coincidence that the flowering of the fairy-tale genre fell on Shchedrin in the 80s. It was during this period of rampant political reaction in Russia that the satirist had to look for a form most convenient for circumventing censorship and at the same time the closest, understandable to the common people. And the people understood the political acuteness of Shchedrin's generalized conclusions hidden behind Aesop's speech and zoological masks. The writer created a new, original genre of political fairy tale, which combines fantasy with real, topical political reality.

In Shchedrin's tales, as in all his work, two social forces are opposed: the working people and their exploiters. The people appear under the masks of kind and defenseless animals and birds (and often without a mask, under the name "man"), the exploiters - in the guise of predators. The symbol of peasant Russia is the image of Konyaga - from the fairy tale of the same name. Konyaga is a peasant, a toiler, a source of life for everyone. Thanks to him, bread grows in the vast fields of Russia, but he himself has no right to eat this bread. His lot is eternal hard labor. “There is no end to work! The whole meaning of his existence is exhausted by his work ... ”- exclaims the satirist. Konyaga is tortured and beaten to the limit, but he alone is able to liberate his native country. “From century to century the formidable immobile bulk of the fields has become numb, as if it is guarding a fabulous power in captivity. Who will free this power from captivity? Who will call her into the light? This task fell to two creatures: the peasant and the Konyag ... This tale is a hymn to the working people of Russia, and it is no coincidence that it had such a great influence on the democratic literature of modern Shchedrin.

In the fairy tale "The Wild Landowner" Shchedrin, as it were, summarized his thoughts on the reform of the "emancipation" of the peasants, contained in all of his works of the 60s. Here he raises an unusually acute problem of the post-reform relationship between the serf-owners and the peasantry finally ruined by the reform: “The cattle will go out to drink - the landowner shouts: my water! the chicken goes out to the outskirts - the landowner shouts: my land! And earth, and water, and air - everything became him! The peasant did not light up Luchina in the light, the rod was gone, how could he sweep the hut. So the peasants all over the world prayed to the Lord God: - Lord! it is easier for us to be abyss with children and small ones, than to languish like that all our life! "

This landowner, like the generals from the tale of two generals, had no idea of work. Abandoned by his peasants, he immediately turns into a filthy and wild animal. He becomes a forest predator. And this life, in essence, is a continuation of his previous predatory existence. The wild landowner, like the generals, takes on an external human appearance only after his peasants return. Scolding the wild landowner for his stupidity, the police chief tells him that without peasant "taxes and duties" the state "cannot exist", that without peasants everyone will die of hunger, "you cannot buy a piece of meat or a pound of bread in the bazaar" and money from there will be no masters. The people are the creator of wealth, and the ruling classes are only consumers of this wealth.

The petitioner raven turns to all the highest authorities of his state in turn, begging to improve the unbearable life of the peasant crows, but in response he hears only "cruel words" that they cannot do anything, because under the existing system the law is on the side of the strong. “Whoever prevails is right,” the hawk instructs. “Look around - there is strife everywhere, everywhere there is a quarrel,” the kite echoes. This is the "normal" state of a proprietary society. And although "the crow lives in society, like real men", it is powerless in this world of chaos and predation. The men are defenseless. “They are firing at them from all sides. Now the railway will shoot, now the car is new, now the crop fails, now the extortion is new. And they just know they turn over. How did it happen that Guboshlepov got his way? After that, the hryvnia in their purse decreased - how can a dark person understand this? * the laws of the world around them.

The crucian carp from the tale “Crucian carp the idealist” is not a hypocrite, he is truly noble, pure in soul. His socialist ideas deserve deep respect, but the methods of their implementation are naive and ridiculous. Shchedrin, being himself a socialist by conviction, did not accept the theory of the utopian socialists, he considered it the fruit of an idealistic view of social reality, of the historical process. “I don’t believe ... that struggle and quarrels were a normal law, under the influence of which everything living on earth was supposedly destined to develop. I believe in bloodless prosperity, I believe in harmony ... ”- the crucian ranted. It ended up being swallowed by a pike, and swallowed mechanically: she was struck by the absurdity and strangeness of this sermon.

In other variations, the idealist crucian carp theory was reflected in the tales The Selfless Hare and The Sane Hare. Here the heroes are not noble idealists, but ordinary cowards, hoping for the kindness of predators. Hares do not doubt the right of the wolf and the fox to take their lives, they consider it quite natural that the strong eat the weak, but they hope to touch the wolf's heart with their honesty and obedience. "Or maybe the wolf ... ha-ha ... will have mercy on me!" Predators remain predators. Zaitsev is not saved by the fact that they “didn’t start up revolutions, they didn’t come out with weapons in their hands”.

Shchedrin's wise gudgeon - the hero of the fairy tale of the same name - became the personification of the wingless and vulgar philistine. The meaning of life of this "enlightened, moderately liberal" coward was self-preservation, avoiding clashes, from struggle. Therefore, the gudgeon lived to a ripe old age unharmed. But what a humiliating life it was! It all consisted of a continuous trembling for its skin. "He lived and trembled - that's all." This fairy tale, written during the years of political reaction in Russia, hit the liberals, creeping in front of the government because of their own skin, without a miss, at the townsfolk who were hiding in their holes from the public struggle. For many years the passionate words of the great democrat have sunk into the souls of the thinking people of Russia: “Those who think that only those minnows can be considered worthy citizens, who, mad with fear, sit in holes and tremble, are wrong. No, these are not citizens, but at least useless minnows. " Shchedrin showed such "minnows" -deepers in the novel "Modern Idyll".

The toptygins from the fairy tale "The Bear in the Voivodeship", sent by the lion to the voivodeship, set as much "bloodshed" as possible with the aim of their reign. By doing this, they aroused the anger of the people, and they suffered the "fate of all fur-bearing animals" - they were killed by the rebels. The same death from the people was accepted by the wolf from the fairy tale "Poor Wolf", which also "robbed day and night." In the fairy tale "The Eagle the Patron" is given a destructive parody of the tsar and the ruling classes. The eagle is the enemy of science, art, protector of darkness and ignorance. He destroyed the nightingale for his free songs, the literate woodpecker "dressed up ... in shackles and imprisoned in a hollow forever", ravaged the raven-men to the ground. In the end, the crows rebelled, "the whole herd took off and flew away," leaving the eagle to starve to death. "Let this be a lesson for the eagles!" - the satirist concludes the tale meaningfully.

All of Shchedrin's tales were subjected to censorship persecution and many alterations. Many of them were published in illegal publications abroad. The masks of the animal world could not hide the political content of Shchedrin's tales. The transfer of human traits, both psychological and political, to the animal world created a comic effect, clearly exposed the absurdity of existing reality.

The fantasy of Shchedrin's tales is real, it carries a generalized political content. Eagles are "predatory, carnivorous ..." They live "in alienation, in inaccessible places, they do not engage in hospitality, but they plunder" - this is what the tale of the eagle-medenate says. And this immediately draws the typical circumstances of the life of a royal eagle and makes it clear that we are not talking about birds at all. And further, combining the atmosphere of the avian world with affairs by no means avian, Shchedrin achieves lofty political pathos and caustic irony. There is also a tale about the Toptygin, who came to the forest to "pacify internal adversaries". Do not obscure the political meaning of the beginnings and endings, taken from magical folk tales, the image of Baba Yaga, Leshy. They only create a comic effect. The discrepancy between form and content contributes here to a sharp exposure of the properties of a type or circumstance.

Sometimes Shchedrin, having taken traditional fairy-tale images, does not even try to introduce them into a fairy-tale setting or use fairy-tale techniques. Through the lips of the heroes of the tale, he directly expresses his idea of social reality. Such is, for example, the fairy tale "Neighbors".

The language of Shchedrin's tales is deeply popular, close to Russian folklore. The satirist uses not only traditional fairy-tale techniques, images, but also proverbs, sayings, sayings ("If you don't give a word, hold on, but if you give it, hold on!" , "My hut is on the edge", "Simplicity is worse than theft"). The dialogue of the characters is colorful, the speech depicts a specific social type: an imperious, rude eagle, a beautiful-minded idealistic crucian carp, an evil reactionary blush, a prude of a priest, a dissolute canary, a cowardly hare, etc.

The images of fairy tales have come into use, have become common nouns and live for many decades, and the common human types of objects of Saltykov-Shchedrin's satire are still found in our life today, it is enough just to take a closer look at the surrounding reality and reflect.

Grotesque is a term that means a type of artistic imagery (image, style, genre) based on fantasy, laughter, hyperbole, bizarre combination and contrast of something with something.

In the genre of the grotesque, the ideological and artistic features of Shchedrin's satire were most clearly manifested: its political acuteness and purposefulness, the realism of its fantasy, the ruthlessness and depth of the grotesque, the crafty sparkling humor.

Shchedrin's “Fairy Tales” in miniature contain the problems and images of the entire work of the great satirist. If, except for "Tales", Shchedrin wrote nothing, then they alone would have given him the right to immortality. Of the thirty-two tales of Shchedrin, twenty-nine were written by him in the last decade of his life and, as it were, sum up the forty-year creative activity of the writer.

Shchedrin often resorted to the fabulous genre in his work. There are elements of fairy-tale fantasy in The History of a City, while the satirical novel Modern Idyll and the chronicle Abroad include completed fairy tales.

And it is no coincidence that the flowering of the fairy tale genre falls on Shchedrin in the 80s of the 19th century. It was during this period of rampant political reaction in Russia that the satirist had to look for a form most convenient for circumventing censorship and at the same time the closest, understandable to the common people. And the people understood the political acuteness of Shchedrin's generalized conclusions hidden behind the Aesopian speech and zoological masks. The writer created a new, original genre of political fairy tale, which combines fantasy with real, topical political reality.

In Shchedrin's tales, as in all his work, two social forces are opposed: the working people and their exploiters. The people appear under the masks of kind and defenseless animals and birds (and often without a mask, under the name "man"), the exploiters - in the guise of predators. And this is already grotesque.

"And I, if they saw: a man is hanging outside the house, in a box on a rope, and smears the wall with paint, or on the roof, like a fly, walks - this is he who I am!" - says the generals the savior-man. Shchedrin laughs bitterly at the fact that the peasant, by order of the generals, twists a rope himself, with which they then tie him up. Almost in all fairy tales the image of the peasant-people is described by Shchedrin with love, breathes with indestructible power and nobility. The man is honest, straightforward, kind, unusually sharp-witted and clever. He can do anything: get food, sew clothes; he conquers the elemental forces of nature, jokingly swims across the "ocean-sea". And the peasant treats his enslavers mockingly, without losing his self-esteem. The generals from the fairy tale “How One Man Fed Two Generals” look pitiful pygmies in comparison with the giant man. To depict them, the satirist uses completely different colors. They do not understand anything, they are dirty physically and spiritually, they are cowardly and helpless, greedy and stupid. If you are looking for animal masks, then a pig mask is just right for them.

In the fairy tale "The Wild Landowner" Shchedrin summarized his thoughts on the reform of the "emancipation" of the peasants, contained in all of his works of the 60s. Here he raises an unusually acute problem of the post-reform relationship between the serf-nobility and the peasantry, which was finally devastated by the reform: “The cattle will go out to drink - the landowner shouts: my water! the chicken goes out to the outskirts - the landowner shouts: my land! And earth, and water, and air - everything became him! "

This landowner, like the aforementioned generals, had no idea about work. Abandoned by his peasants, he immediately turns into a dirty and wild animal, becomes a forest predator. And this life, in essence, is a continuation of his previous predatory existence. The wild landowner, like the generals, takes on an external human appearance only after his peasants return. Scolding the wild landowner for his stupidity, the police chief tells him that the state cannot exist without peasant taxes and duties, that without the peasants everyone will die of hunger, at the bazaar it is impossible to buy a piece of meat or a pound of bread, and the gentlemen will not have any money. The people are the creators of wealth, and the ruling classes are only consumers of this wealth.

The crucian carp from the tale “Crucian carp the idealist” is not a hypocrite, he is truly noble, pure in soul. His socialist ideas deserve deep respect, but the methods of their implementation are naive and ridiculous. Shchedrin, being himself a socialist by conviction, did not accept the theory of the utopian socialists, he considered it the fruit of an idealistic view of social reality, of the historical process. “I don’t believe ... that struggle and quarrels were a normal law, under the influence of which everything living on earth was supposedly destined to develop. I believe in bloodless success, I believe in harmony ... ”- the crucian ranted. It ended up being swallowed by a pike, and swallowed mechanically: she was struck by the absurdity and strangeness of this sermon.

In other variations, the idealist crucian carp theory was reflected in the tales “The Selfless Hare” and “The Sane Hare”. Here the heroes are not noble idealists, but ordinary cowards, hoping for the kindness of predators. Hares do not doubt the right of the wolf and the fox to take their lives, they consider it quite natural that the strong eat the weak, but they hope to touch the wolf's heart with their honesty and obedience. "Or maybe the wolf ... ha-ha ... will have mercy!" Predators remain predators. Zaitsev is not saved by the fact that they “didn’t start up revolutions, they didn’t come out with weapons in their hands”.

Shchedrin's wise gudgeon - the hero of the fairy tale of the same name - became the personification of the wingless and vulgar philistine. The meaning of life of this "enlightened, moderately liberal" coward was self-preservation, avoiding collisions, from struggle. Therefore, the gudgeon lived to a ripe old age unharmed. But what a humiliating life it was! It all consisted of a continuous trembling for its skin. "He lived and trembled - that's all." This fairy tale, written during the years of political reaction in Russia, hit the liberals, creeping in front of the government because of their own skin, without a miss, at the townsfolk who were hiding in their holes from the public struggle.

The toptygins from the fairy tale "The Bear in the Voivodeship", sent by the lion to the voivodeship, set as much "bloodshed" as possible with the aim of their reign. By doing this, they aroused the anger of the people, and they suffered “the fate of all fur-bearing animals” - they were killed by the rebels. The same death from the people was accepted by the wolf from the fairy tale “Poor Wolf”, which also “robbed day and night”. In the fairy tale "The Eagle the Patron" is given a destructive parody of the tsar and the ruling classes. The eagle is the enemy of science, art, protector of darkness and ignorance. He destroyed the nightingale for his free songs, literate the woodpecker “dressed up. ... "Let this be a lesson for the eagles!" - the satirist concludes the tale meaningfully.

All of Shchedrin's tales were subjected to censorship persecution and alterations. Many of them were published in illegal publications abroad. The masks of the animal world could not hide the political content of Shchedrin's tales. The transfer of human traits - psychological and political - to the animal world created a comic effect, clearly exposed the absurdity of existing reality.

The images of fairy tales have come into use, have become common nouns and live for many decades, and the common human types of objects of Saltykov-Shchedrin's satire are still found in our life today, it is enough just to take a closer look at the surrounding reality and reflect.

9. Humanism of Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel "Crime and Punishment"

« The willful murder of even the last of people, the most harmful of people, is not permitted by the spiritual nature of man ... The eternal law came into its own, and he (Raskolnikov) fell under his rule. Christ did not come to violate, but to fulfill the law ... Those who were truly great and genius, who performed great deeds for all mankind, did not act like that. They did not consider themselves supermen, to whom everything is permitted, and therefore could give a lot to the "human" (N. Berdyaev).

Dostoevsky, by his own admission, was worried about the fate of "nine-tenths of humanity", morally humiliated, socially disadvantaged in the conditions of his contemporary bourgeois system. Crime and Punishment is a novel that reproduces pictures of the social suffering of the urban poor. Extreme poverty is characterized by "nowhere else to go". The image of poverty is constantly changing in the novel. This is the fate of Katerina Ivanovna, who remained after the death of her husband with three young children. This is the fate of Mar-Meladov himself. The tragedy of a father forced to accept the fall of his daughter. The fate of Sonya, who committed the "feat of crime" on herself for the sake of love for her loved ones. The torment of children who grew up in a dirty corner, next to a drunken father and a dying, irritated mother, in an atmosphere of constant quarrels.

Is the destruction of the "unnecessary" minority acceptable for the sake of the happiness of the majority? Dostoevsky answers with all the literary content of the novel: no - and consistently refutes Raskolnikov's theory: if one person arrogates to himself the right to physically destroy an unnecessary minority for the sake of the happiness of the majority, then “simple arithmetic” will not work: apart from the old woman-pawnbroker, Raskolnikov also kills Lizaveta the most humiliated and insulted, for the sake of which, as he is trying to convince himself, the ax was raised.

If Raskolnikov and others like him take on such a lofty mission - defenders of the humiliated and insulted, then they must inevitably consider themselves extraordinary people to whom everything is allowed, that is, they inevitably end up with contempt for the very humiliated and insulted whom they defend.

If you allow yourself "blood according to your conscience", you will inevitably turn into Svidrigailov. Svidri-gailov - the same Raskolnikov, but already finally "corrected" from all prejudices. Svid-rigailov blocks all paths to Raskolnikov that lead not only to repentance, but even to a purely official confession. And it is no coincidence that only after Svidrigailov's suicide Raskolnikov makes this confession.

The most important role in the novel is played by the image of Sonya Marmeladova. Active love for one's neighbor, the ability to respond to someone else's pain (especially deeply manifested in the scene of Raskolnikov's confession of murder) make the image of Sonya ideal. It is from the standpoint of this ideal that the verdict is pronounced in the novel. For Sonya, all people have the same right to life. No one can seek happiness, his own or someone else's, by crime. Sonya, according to Dostoevsky, embodies the folk principle: patience and humility, immeasurable love for man.

Only love saves and reunites a fallen person with God. The power of love is such that it can help save even such an unrepentant sinner as Raskolnikov.

The religion of love and self-sacrifice acquires an exceptional and decisive significance in Dostoevsky's Christianity. The idea of the inviolability of any human person plays a major role in understanding the ideological meaning of the novel. In the image of Ras-Kolnikov, Dostoevsky executes the denial of the intrinsic value of the human person and shows that any person, including the disgusting old woman-usurer, is sacred and inviolable, and in this respect people are equal.

Raskolnikov's protest is associated with acute pity for the poor, suffering and helpless.

10. The theme of the family in the novel by Leo Tolstoy "War and Peace"

The idea of the spiritual foundations of nepotism as an external form of unity between people received a special expression in the epilogue of the novel "War and Peace". In the family, as it were, the opposition between the spouses is removed, in the communication between them, the limitations of loving souls complement each other. Such is the family of Marya Bolkonskaya and Nikolai Rostov, where such opposite principles of the Rostovs and Bolkonsky are combined in a higher synthesis. Wonderful is the feeling of Nikolai's “proud love” for Countess Marya, based on surprise “before her soulfulness, before that almost inaccessible to him, sublime, moral world in which his wife has always lived”. And the submissive, tender love of Marya "for this man who will never understand everything that she understands, and as if from this she loved him even more, with a tinge of passionate tenderness, is touching."

In the epilogue of War and Peace, a new family gathers under the roof of the Lysogorsk house, uniting in the past heterogeneous Rostov, Bolkonian, and, through Pierre Bezukhov, also Karataev principles. “As in a real family, in the Lysogorsk house several completely different worlds lived together, which, each holding its own peculiarity and making concessions to one another, merged into one harmonious whole. Every event that happened in the house was equally important - joyful or sad - for all these worlds; but each world had completely its own, independent from others, reasons to rejoice or grieve at any event. "

This new family did not arise by accident. It was the result of the nationwide unity of people born of the Patriotic War. This is how the epilogue reaffirms the connection between the general course of history and individual, intimate relationships between people. The year 1812, which gave Russia a new, higher level of human communication, removed many class barriers and restrictions, led to the emergence of more complex and wider family worlds. The keepers of the family foundations are women - Natasha and Marya. There is a strong, spiritual union between them.

Rostovs. The writer is especially sympathetic to the patriarchal family of the Rostovs, in whose behavior a high nobility of feelings, kindness (even rare generosity), naturalness, closeness to the people, moral purity and integrity are manifested. The Rostovs' courtyards - Tikhon, Prokofy, Praskovya Savvishna - are devoted to their masters, feel like one family with them, show understanding and show attention to the interests of the lord.

Bolkonskys. The old prince represents the flower of the nobility of the era of Catherine II. He is characterized by true patriotism, breadth of political horizons, understanding of the true interests of Russia, indomitable energy. Andrey and Marya are progressive, educated people looking for new ways in modern life.

The Kuragin family brings only troubles and misfortunes to the peaceful "nests" of the Rostovs and Bolkonskys.

Under Borodin, at the Rayevsky battery, where Pierre falls, one can feel "common to everyone, like a family revival." “The soldiers ... mentally took Pierre into their family, appropriated and gave him a nickname. "Our master" they nicknamed him and they laughed affectionately about him among themselves. "

So the feeling of family, which in a peaceful life is sacredly cherished by those close to the people of Rostov, will turn out to be historically significant during the Patriotic War of 1812.

11. Patriotic theme in the novel "War and Peace"

In extreme situations, in moments of great shocks and global changes, a person will definitely show himself, show his inner essence, certain qualities of his nature. In Tolstoy's novel War and Peace, someone utters loud words, is engaged in noisy activities or useless vanity, someone experiences a simple and natural feeling of “the need for sacrifice and suffering in the face of common misfortune.” The former only think of themselves as patriots and loudly shout about love for the Fatherland, while the latter, essentially patriots, give their lives for the sake of common victory.

In the first case, we are dealing with false patriotism, repulsive with its falsehood, selfishness and hypocrisy. This is how secular nobles behave at a dinner in honor of Bagration; when reading poems about the war, "everyone stood up, feeling that dinner was more important than poetry." A pseudo-patriotic atmosphere reigns in the salon of Anna Pavlovna Sherer, Helen Bezukhova and in other St. Petersburg salons: “... calm, luxurious, concerned only with ghosts, reflections of life, St. Petersburg life was going on in the old way; and because of the course of this life it was necessary to make great efforts to realize the danger and the difficult situation in which the Russian people found themselves. There were the same exits, balls, the same French theater, the same interests of the courtyards, the same interests of service and intrigue. This circle of people was far from understanding all-Russian problems, from understanding the great misfortune and need of the people in this war. The world continued to live by its own interests, and even in a moment of national disaster, greed, promotion, and service reign here.

Count Rostopchin also manifests pseudo-patriotism, posting stupid "posters" around Moscow, urging residents of the city not to leave the capital, and then, fleeing the people's wrath, deliberately sends the innocent son of the merchant Vereshchagin to death.

A false patriot is presented in the novel by Berg, who, in a moment of general confusion, is looking for an opportunity to profit and is preoccupied with buying a wardrobe and a toilet "with an English secret." It does not even occur to him that now it is a shame to think about wardrobes. Such is Drubetskoy, who, like other staff officers, thinks about awards and promotions, wants to "arrange for himself the best position, especially the position of adjutant to an important person, which seemed to him especially tempting in the army." Probably, it is no coincidence that on the eve of the Battle of Borodino, Pierre notices this greedy excitement on the faces of the officers; he mentally compares it with "another expression of excitement", "which spoke of not personal, but general issues, matters of life and death."

What "other" persons are we talking about? These are the faces of ordinary Russian men, dressed in soldier's greatcoats, for whom the feeling of the Motherland is sacred and inalienable. True patriots in Tushin's battery are fighting without cover. And Tushin himself "did not experience the slightest unpleasant feeling of fear, and the idea that he could be killed or hurt painfully did not occur to him." The living, bloodthirsty feeling of the Motherland forces the soldiers to resist the enemy with inconceivable staunchness. The merchant Ferapontov, who gives up his property for plunder when Smolensk is abandoned, is also, of course, a patriot. "Bring everything, guys, don't leave it to the French!" he shouts to the Russian soldiers.

Pierre Bezukhov gives his money, sells his estate to equip the regiment. A sense of concern for the fate of his country, involvement in a common grief makes him, a wealthy aristocrat, go into the heat of the Battle of Borodino.

Those who left Moscow, not wanting to submit to Napoleon, were also true patriots. They were convinced: "It was impossible to be under the control of the French." They "simply and truly" did "that great deed that saved Russia."

Petya Rostov is eager to go to the front, because "Fatherland is in danger." And his sister Natasha frees carts for the wounded, although without family good she will remain a dowry.

True patriots in Tolstoy's novel do not think about themselves, they feel the need for their own contribution and even sacrifice, but they do not expect a reward for this, because they carry in their souls a genuine sacred feeling of the Motherland.