The main idea of the first movement of the Moonlight Sonata. Beethoven - Moonlight Sonata

Beethoven's Sonata "Quasi una Fantasia" cis-moll ("Moonlight")

The history of the origin of "Lunar" - both the sonata itself and its name - is widely known. The article offered to the reader's attention does not contain any new data of this kind. Its goal is to analyze the “complex of artistic discoveries” with which this unique work of Beethoven is so rich; consideration of the logic of thematic development associated with a whole system of expressive means. Finally, behind all of the above, there is a kind of super task - to reveal the inner essence of the sonata as a living artistic organism, as one of the many expressions of Beethoven's spirit, to reveal the specific uniqueness of this particular creative act of the great composer.

Three parts of "Lunar" - three stages in the process of the formation of a single artistic idea, three stages, reflecting a purely Beethoven method of embodiment of the dialectical triad - thesis, antithesis, synthesis *. This dialectical triad is the basis of many laws of music. In particular, both sonata and sonata-cyclical forms owe a lot to her. The article attempts to reveal the specifics of this triad both in Beethoven's work as a whole and in the sonata being analyzed.

One of the features of its embodiment in the work of the great composer is an explosion - a sharp qualitative change in the transition to the third link with an instant release of powerful energy.

In Beethoven's work of the mature period, a dramatic complex operates: movement - inhibition - the emergence of an obstacle - the instant overcoming of the latter. The formulated triad is embodied at various levels - from the functional plan of the theme to the construction of a whole work.

The main part "Appassionata" is an example in which the first eight measures (the first two elements, given in the comparison of f-minor and Ges-major) - action, the appearance of the third element and the resulting fragmentation, the struggle of the second and third elements - inhibition, and the final passage sixteenths - explosion.

A similar functional relationship is found in the main game of the first part of "Heroic". The initial fanfare themed seed is action. The appearance of the cis sound in the bass, syncopation in the upper voice, deviation in g-moll - an obstacle, a diverging scale-like move completing the sentence with a return to Es - overcoming. This triad governs the development of the entire exhibition. In the second sentence of the main party, the overcoming of the obstacle (powerful syncopations) also occurs by means of a similar diverging scale. The third sentence in the same way leads to the exit to the dominant B-dur. The pre-ordinary theme - (the compositional functions of this theme are the combination of the pre-act before the side part - the dominant organ point - with the presentation of the new theme; but from the fact that such a significant musical idea is expressed here, its dramatic function of the side part follows) - a roll call of woodwind and violins in syncopated rhythm is an obstacle arising at a higher level of action, in which the first member of the triad is the entire main party. A careful analysis can reveal the effect of this method throughout not only the exposure, but throughout the entire first part.

Sometimes, with a continuous succession of touching links, a kind of dramatic ellipsis can arise, as, for example, in the development center, when the development of rhythm figure leads to heightened dissonant syncopations - the real embodiment of the idea of a surmounted obstacle. Both members of the triad merge into one whole, and the next episode in e-moll introduces a sharp contrast: the lyrics are an obstacle to the heroic (the embodiment of this inside the exhibition is moments of lyrical calm).

In 32 variations appears, as L.A. Mazel writes,

"Characteristic series" - a group of variations that implement this principle in a special form (variations with lively movement, lyrical, "quiet" variation and a group of "loud" dynamically active variations arising in the form of an explosion - for example, VII-VIII, IX, X-XI variations).

Various variants of the triad are also formed at the level of the cycle. The most peculiar solution is the articulation of the third and fourth movements of the Fifth Symphony. In the first section "scherzo" (Beethoven does not give this name, and it is hardly fair to call this part so without reservations), where there is a return to the idea of the first part - the idea of struggle, the first element of the triad - action - is realized. A striking artistic discovery was that the "antithesis" - an obstacle - was embodied by the composer not by a contrasting thematic construction, but by a variant of the initial one: a "muffled" reprise becomes the expression of the second joint of the triad. “The famous transition to the finale,” writes S. E. Pavchinsky, “is something completely new. ... Beethoven here reached an exhaustive completeness and no longer repeated himself in this (the concept of the Ninth Symphony is by no means identical with the Fifth). "

S. Pavchinsky rightly points to the "completeness" of the expression of Beethoven's technique. But it can be considered "exhaustive" only in the aspect of this solution of the problem, when the function of the explosion is performed by the famous dominant dynamic growth and the major tonic that arises as a result. In the Ninth Symphony, Beethoven really finds a different solution, but on the basis of the same triad, when the third movement - a lyrical digression - is replaced by the shock beginning of the finale. A dramatic passage announcing the overcoming of the lyrics becomes, in the order of a dramatic ellipsis, the beginning of a new stage - movement, recitative - a brake; the moment of overcoming is stretched - the emergence of the theme of joy in the quiet basses is a unique case: the place of the explosion is a retreat into the area of the most hidden, distant ("anti-explosion").

The dramatic function of the explosion is carried out in the development of variations. All further movement of the music of the finale goes through a number of triad links.

In Lunar, Beethoven's dramatic method receives an individual solution. This sonata is one of Beethoven's relatively early creations, and it can be assumed that the peculiarities of the embodiment of the triad were the result of both the specificity of the concept and the dramatic principles of the composer not yet fully formed. "Triad" is not a Procrustean bed, but a general principle, solved in each case differently. But the most specific of the "triad" is already expressed in the "Lunar".

The music of the finale is the otherness of the music of the first movement. The artistic essence of all parts will be considered further, but even without analysis it is clear that the Adagio conveyed an internally focused deepening into one idea. In the finale, however, this latter is embodied in a violently effective aspect; that which in Adagio was constrained, concentrated in itself, directed inward, in the final, as it were, finds a way out, is directed outward. The sorrowful consciousness of life's tragedy turns into an explosion of furious protest. Sculptural statics are replaced by the rapid movement of emotions. The turning point is due to the character of the second movement of the sonata. Let us recall Liszt's words about Allegretto - “a flower between two abysses”. All the music of this quasi-scherzo conveys something very far from the profound philosophical nature of the first movement, on the contrary, it reveals the immediate, simple and trusting (like a ray of the sun, a smile of a child, the chirping of birds) - that which opposes the darkness of the tragedy of Adagio thought: life itself is herself beautiful. Comparison of the first two parts generates a psychological reaction - one must live, act, fight.

Beethoven's hero, as if waking up from mournful self-absorption under the influence of a smile of simple joy that flashed before his eyes, instantly ignites - the joy of the upcoming struggle, anger, rage of indignation replace the previous reflection.

R. Rolland wrote about the internal connection of the three parts of the sonata: “This playing, smiling grace must inevitably cause — and indeed does — an increase in sorrow; her appearance turns the soul, at first crying and depressed, into a fury of passion. " “The tragic mood, restrained in the first part, breaks through here in an unrestrained stream,” writes V. D. Konen. There is only one step from these thoughts to the idea of the complete dialectical unity of the Lunar cycle.

In addition, another psychological complex is reflected in the essay being analyzed.

Let us recall Dante's verses - "there is no greater torment than remembering the days of past joy in days of sorrow." What was said in a short phrase for its embodiment also requires a triad: restrained sadness - an image of past joy - a stormy outburst of grief. This triad, embodying psychological truth and dialectic of feelings, is reflected in various musical works. In Lunar, Beethoven found a special version, the specificity of which lies in the third link - not an outburst of grief, but an outburst of protesting anger - the result of what he had experienced. It can be understood that the dramatic formula of Lunar combines the essence of both triads considered.

Mournful reality - an image of pure joy - a protest against the conditions that give rise to suffering, sorrow. This is the generalized expression of the Lunar drama. This formula, although it does not exactly coincide with Beethoven's triad of the mature period, but, as it was said, is close to it. It also creates a conflict between the first and second links - the thesis and the antithesis, leading to a violent outbreak as a way out of the contradiction.

This output can be very different. For Beethoven's symphonies, a heroic solution to a problem is typical, for his piano sonatas - a dramatic one.

One of the essential differences between these two types of sonata cycles in Beethoven lies precisely in the fact that in sonatas with a dramatic first movement, their author never arrives at the heroic final decision. The otherness of the drama of the first movement ("Appassionata"), its dissolution in folk song versions ("Pathetic"), in the boundless sea of lyric moto perpetuo (Seventeenth Sonata) - these are the options for resolving the conflict. In the later sonatas (e-moll and c-moll), Beethoven creates a "dialogue" of dramatic conflict either with a pastoral idyll (Sonata Twenty-seventh) or with images of high hovering spirit (Sonata Thirty-second).

Lunar, on the other hand, is decisively different from all the other piano sonatas in that the center of drama in it is the last movement. (These are the essential features of Beethoven's innovation. It is known that later - especially in Mahler's symphonies - shifting the center of gravity of the cycle to the finale became one of the forms of drama.)

The composer, as it were, reveals one of the possible ways of creating dramatically effective music, while in other cases it serves as a starting point.

Thus, the drama of this sonata is unique: the finale -

not a solution to the problem, but only its statement. The paradoxical inconsistency of such a drama turns in the hands of a genius into the highest

naturalness. The universal love of the widest masses of listeners, tens of millions of people, captured by the greatness and beauty of this music from the day of its birth, is proof of the rare combination of the richness and depth of ideas with the simplicity and universality of their musical solution.

There are not so many such creations. And each of them requires * special attention. The inexhaustible content of such works makes the forms of their study inexhaustible. This article is just one of many possible research aspects. In its central, analytical section, specific forms of embodiment of the sonata's drama are considered. The analysis of the three parts contains the following internal plan: expressive means - thematism - forms of its development.

In conclusion, there are generalizations of aesthetic and ideological nature.

In the first movement of the sonata - Adagio - the expressive and formative role of texture is very great. Its three layers (AB Goldenveiser states their presence) - the lines of the bass, middle and upper voices - are associated with three specific genre origins.

The first textured layer - the dimensional movement of the lower voice - as if bears the "imprint" of basso ostinato, predominantly descending from the tonic to the dominant with a number of bends and bends. In Adagio, this voice does not stop for a moment - its mournful expressiveness becomes the deep foundation of the complex multi-layered figurative alloy of the first movement. The second textured layer - the pulsation of triplets - originates from the genre of prelude. Bach repeatedly used calm, continuous movement in works of this kind with their deep generalized expressiveness. Beethoven also reproduces the typical harmonic formula of the initial Bach thematic core TSDT, complicating it with chords of the VI degree and II low. In combination with the descending bass, all this testifies to the existence of significant connections with the art of Bach.

The metro-rhythmic design of the main formula plays a decisive role. In this case, in Adagio, both sizes are combined - 4X3. Perfect squareness in the scale of a bar and three-dimensionality in terms of its beat. The two main sizes coexist and join forces. The triplets create the effect of roundness, rotation that permeates Adagio; a lot is connected with them in the essence of the expressiveness of the first movement of "Lunar".

It is thanks to this rhythmic formula that a deep, through emotion comprehensible embodiment of an artistic idea arises - a kind of projection of a non-stop objective progressive movement onto the plane of a person's mental world. Each triplet, with a rotational movement along chord sounds, is a spiral curl; The accumulated gravitation of the two lighter beats (the second and third eighth of each triplet) does not lead forward in an ascending direction, but returns to the original low point. As a result, an unrealizable inertial linear gravitation is created.

A regular and evenly repeated return to the lower sound and an equally uniform and regular movement ascending from it, not interrupted for a moment, gives rise to the effect of a spiral going into infinity, a movement of a constrained, not finding an outlet, concentrated in itself. The minor mode defines a deep mournful tone.

The role of the uniformity of movement is also great. The time-measuring side of rhythm * is clearly revealed in it. Each triplet measures a fraction of the time, the quarters collect them in three, and the bars in twelve. The invariable alternation of heavy and light bars (two bars) is twenty-four.

The analyzed Adagio is a rare example of such a ramified metric organization in slow tempo music with a complex meter. This creates a special expressiveness. This is how seconds, minutes and hours of running time are measured. We "hear" it in moments of special mental concentration, in moments of lonely deepening into the world around us. Thus, before the mental gaze of the thinker, days, years, centuries of human history pass in a measured succession. Concise and organized time as the most important factor determining our life - this is one of the sides of the expressive power of Adagio.

An even movement in C major in a higher and lighter register is the basis of Bach's Prelude in C major. Here, the time measurement under the conditions of an absolutely square movement (4X4) and a different textured formula embodies a softer, more gentle and blissful image. The legend of the Annunciation, associated with the idea of prelude (the descent of an angel), suggests a luminous generalization of the eternal image of the current time. Closer to "Lunar" there is a uniform movement with the same 4X3 formula in the introduction of Mozart's Fantasy d-moll. The minor and the descending bass formula create a more Beethoven-like image, but the low register and wide arpeggiated movement bring a dark flavor to life. Here the genre of prelude is embodied by Mozart in its purest form - this episode becomes just an introduction to the fantasy itself.

In Adagio, the initial impulse is very important - the first figurations of triplets outline the movement from fifth to third, forming a "lyric sixth" (The idea of a "lyric sixth" in the melody was expressed by B.V. Asafiev and developed by L. Mazel.) tone. The lyrical sixth is given here only as a skeleton. Beethoven used it more than once in an intonational-individualized form. Especially significant - in the finale of the sonata in d-moll, where, as if captured by a similar rotational movement, the initial sixth outlines the relief of the melodized cell - the basis of the final moto perpetuo. This seemingly external analogy, however, is essential for understanding the idea of "Lunar" as a whole.

So, an even spiral movement is like circles spreading along the water surface from pebbles evenly falling into it - four quarters. The latter form a square base, they determine the movement of both the bass and the upper voice. The upper voice is the third layer of the Adagio texture. The initial core is the recitative of the upper voice - the first five bars of the theme itself - the movement from the fifth cis-minor to the E-dur prim. The questioning character of the fifth is clearly embodied in Adagio. The turn of T-D, D-T creates a complete logical whole within a two-bar - a phrase of a question-and-answer harmonic movement, which, however, does not give permission thanks to the fifth ostinato of the upper voice.

Let us name the similar fifth ostinato in Beethoven: Marcia funebre from the Twelfth Sonata, Allegretto from the Seventh Symphony, the initial impulse from the second movement of the Third Symphony.

The expressive value of the emphasis on the fifth, its “fatal” character, is confirmed decades later in the works of various composers, for example, in Wagner (in the Funeral March from The Death of the Gods), in Tchaikovsky (in Andante from the Third Quartet).

The analogy with Marcia funebre from Beethoven's Twelfth Sonata, written quite shortly before Lunar, turns out to be especially convincing. Moreover, the initial sentence of the theme from "Lunar" is close to the second sentence of March ** from the Twelfth Sonata ("... the rhythm of the funeral march is" invisibly "present here").

It is also interesting to note the characteristic turn - modulation and melody course from the VI degree of minor to the first degree of the parallel major, used in both sonatas.

The similarities between the sonatas, op. 27 No. 2 and op. 26 is amplified by the appearance after the final cadence of the minor of the same name, which greatly thickens the mourning color of the music (F major - e minor, H major - h minor). A different texture, a new, rare for that time, tonality of cis-moll gives birth to a new version of the mourning image - not a funeral procession, but a mournful reflection on human destinies. Not an individual hero, but humanity as a whole, its destinies - that is what is the subject of mournful reflection. This is also facilitated by the chord basis of the texture - the joint action of three voices. The decomposed triad at a slow pace and in the appropriate register is capable of creating an image of a kind of dispersed chorality, this genre is, as it were, in the depths of our perception, but it directs our consciousness to the path of generalized imagery.

The sublime, the impersonal, generated by the combination of the chorale and the prelude, is combined with the manifestation of the personal - the recitative of the upper voice, turning into arioso. This is how the characteristic of the music of I.S. Bach's one-time contrast.

The combination of two opposite figurative and ideological factors creates the atmosphere of Adagio, its polysemy. Many specific subjective interpretations stem from this. With the inner emphasis of the upper voice, the personal aspect of perception is enhanced; if the focus of the listener's (and the performer's) attention is transferred to the chorale-prelude layer of texture, emotional generalization increases.

The most difficult thing both in performance and in listening to music is to achieve the unity of the personal and the impersonal that is objectively inherent in this music.

The intonational concentration of the initial thematic core extends to the form of Adagio as a whole, to its tonal plane. The first period contains a movement from cis-minor to H-major, that is, to the dominant e-minor. E-moll is, in turn, the key of the same name to E-dur - parallel to cis-moll. The tonal path typical of a sonata exposition is complicated by the major minor tuning of the Adagio.

And nevertheless, being in H-major (with a variable value of the dominant e-moll) determines the thematicism of the “side part” * (NS Nikolaeva writes about the features of sonata in the form of Adagio) - humming of the h sound in the range of a diminished third c-ais ... The aching harmony of II low - an echo of the opening bars, where in the "hidden" voice - a turn in the range of a diminished third.

The analogy with the sonata side part is enhanced by both the readiness of the main motive by the previous development, and especially by its transposition in the reprise, where it sounds in the same key.

Further development after the "side game" leads in the exposition to the cadence in fis-moll and the middle part, in the reprise - to the cadence in cis-minor and to the coda.

Passionate, but restrained, in the culmination of the middle part ("development") of the main thematic recitative nucleus (in the subdominant tonality) meets the gloomy funeral sound of it in the lower voice in the main tonality:

The wide-enveloping passages at the organ point of the dominant (the prediction before the reprise) correspond to similar figurations in the code.

The custom form of Adagio cannot be defined unequivocally. In her three-part composition, the rhythm of the sonata form beats. The latter is given as a hint, the order of thematic and tonal development is close to the conditions of the sonata form. She here, as it were, "breaks through" a path for herself, which is closed to her by the very essence of thematicism and its development. This is how a functional semblance of a sonata form arises. One of the features of the composition of Adagio is successfully captured in G.E. parts. Before him - 27, after him - 28 bars. (Konyus singles out the last bar into a "spire" *. (This is how the author of the theory of metrotectonism calls the last bars, not in the general symmetrical plan of the form of a musical work.) As a result, a strictly organized structure is created in which the introduction and unstable beginning of the "left" part of the form are balanced by the coda Indeed, being within the specified organ point is an essentially noticeable “area of musical action,” and this “location” of it organizes the course of musical development and is perceived without much effort. the truth of the embodied image.

A significant role in the unity of the expressive and form-building functions of Adagio is played by the ostinate violation of squareness within the framework of constructions that go beyond the two-bar. The constant change in the values of phrases, sentences, the dominance of invading cadences contribute to the illusion of improvisational immediacy of the utterance. This is undoubtedly reflected in the title of the sonata given by Beethoven himself: Quasi una fantasia.

The famous researcher of Beethoven's work P. Becker writes: "From the combination of fantasy and sonata, Beethoven's most original creation is born - the fantasy sonata." P. Becker also notes the improvisation of Beethoven's compositional techniques. Interesting is his statement about the finale of Lunar: “In the finale of the cis-moll sonata, there is already an innovation that could have a strong influence on the future form of the sonata: this is an improvisational introduction of the main part. It does not exist in the form of a pre-given, ready-made element, as it has hitherto; it develops before our eyes ... so, in the sonata, the initial passage, which looks only prelude, develops into a theme through periodic repetition. " Further P. Becker expresses the idea that improvisation is only an illusion, a specially calculated device of the composer.

The above can be even more related to the first part. In the finale, her illusory improvisation is just replaced by strict organization. Only in the main party, as P. Becker notes, there are traces of the past. On the other hand, what could not be embodied in Adagio is realized in the final - Presto.

The decisive shift is happening in the microkernel itself. The unrealized inertial upward movement is carried out, a fourth sound arises, closing the figure, breaking the spiral, destroying the triplet.

For accuracy, we note that the first sound in the Adagio - cis melody meets the requirements of linear inertial gravitation, but only partially, as it is superimposed over the triplet texture. In the end, this moment of imaginary realization takes the form of an acting factor. Instead of 4X3, 4X4 now appears - a "staircase" of uplifting quarters * rushing along an ascending line is created * (V.D.Konen writes about the connection of the arpeggios of the extreme parts).

The finale is the true otherness of Adagio. Everything that in the first part was connected with the spiral, that was limited by it, is now embodied in the conditions of free aspiring movement. The almost complete identity of the bass voice is striking. In this sense, the main part of the finale is a kind of variation on the figured basso ostinato of the first movement.

Hence the paradoxical nature of the thematism. The main part function is combined with the intro function. The role of the main theme is transferred to the side party - only in it an individualized theme appears.

The idea of “otherness” is manifested in something else as well. The fifth sound of the recitative of the first movement is stratified. In the main part of the finale, the quint tone is realized in two beats of chords, in the side quint gis - the main persistent sound of her melody. The punctured rhythm against the background of smooth movement is also the "heritage" of Adagio.

At the same time, the emerging melody links are a new melodic version of the extended Adagio formula. The move е1-cis1-his is the reincarnation of the melody of the voice that sounds in the precursor to the Adagio reprise. (This voice, in turn, is associated with the bass move in the "side" part of Adagio)

The considered melody is at the same time one of the thematic ideas "floating" in the air. We will find its prototype in the sonata by F.-E. Bach.

The beginning of Mozart's sonata a-moll is also close both in melodic contours and in the emotional content hidden behind them.

Let's return, however, to Beethoven. The move from e to his and back is fixed in the final game in the upper and middle votes.

The brief thematic impulse of Adagio thus stimulates the development of the Presto exposition. The functional semblance of the sonata form in the Adagio is transformed into a true sonata form of the finale. The rhythm of the sonata form, being bound by the spiraling movement of the first movement, is released and brings to life the true sonata form of the finale.

The influence of the first part also affects the role of the Presto connecting party. In the exposition, it is only a "technical necessity" for modulation into a dominant tonality. In the reprise, the internal connection of the finale with the first movement is clearly outlined: just as in Adagio, the introduction introduced directly into the main and only theme, so in the reprise of the finale, the former introduction - now the main part - directly introduces into the main (but now not the only) theme - the side party.

The dynamism of the main artistic idea of the finale requires a wider thematic framework and broader development. Hence the two themes of the final installment. The second one is synthetic. The e-cis-his move is the "legacy" of the previous motive, and the repetition of the fifth is the initial recitative of the first movement.

Thus, the entire section of the side and final games of the finale corresponds on the whole to the development of the only theme of the first part.

The contours of the finale's sonata form are also the otherness of the Adagio form. The middle section of the Adagio (a kind of development) consists of two large sections: five bars of the theme in fis-moll and fourteen bars of the dominant organ point. The same is observed in the final. The development of the finale (now genuine) consists of two sections: conducting the main theme of the finale, its secondary part in fis-moll with a deviation into the key of II low * (For the role of this harmony, see below) and a 15-bar dominant pre-act.

Such a "stingy" tonal plan is atypical for Beethoven's sonata form in such an intensely dramatic music. S. E. Pavchinsky notes both this and other features of the finale structure. All of them are explained precisely by the fact that the Presto form is the otherness of the Adagio form. But the noted specificity of the tonal plan plays an important role, contributing to the special solidity and process of musical development of the sonata as a whole, and its crystallized result.

And the code of the final is also the otherness of the code of Adagio: again, the main theme sounds in the main key. The difference in the form of its presentation corresponds to the ideological difference of the finale: instead of the culmination of hopelessness and sadness of the first movement, here is the culmination of dramatic action.

In both extreme parts of "Lunar" - both in Adagio and in Presto - the sound and harmony of II low plays a significant role (for a description of these examples, see V. Berkov's book "Harmony and Musical Form"). Their initial formative role is to create heightened tension at the moment of development, often at its culmination. The first measure of the intro is the initial core. Its variant development, based on the descending bass, culminates in the Neapolitan sixth chord - this is the moment of the greatest divergence of the extreme voices, the appearance of an octave between them. It is also significant that this moment is the point of the golden section of the initial four-bar. Here is the beginning of the middle voice d-his-cis, the humming of the reference sound within the smallest possible intervals - the diminished third, which creates a special condensed intonation tension, well corresponding to the climax of this moment.

The "side batch" of Allegro is the beginning of the development that emerges after the modulating period (the "main batch"). There is a combination of functions ("switching of functions" according to BF Asafiev). The moment of development - the "side party" - connects with a new thematic impulse. The singing move of the introduction IIн - VIIc - I sounds (a little differently) in the upper voice. (This moment coincides with the point of the golden section of "exposure" (v. 5-22): bar 12 of 18 (11 + 7).) This motive makes remember Kyrie No. 3 from the Mass h-moll by IS Bach - another example of the connection with the art of the great polyphonist.

Due to the organ point in the bass on the tonic, a nagging dissonance of the minor nona is formed. So the development of Neapolitan harmony creates an impulse for the emergence of a small non-chord - the second leitharmony of the extreme parts. From now on, the moments of culmination will be marked by both the one and the other leitharmony, and II low will receive a new functional meaning - pre-cade turnover, which arises at the end of the Adagio exposition.

In the middle section of Adagio ("development"), the harmony of the dominant non-chord comes to the fore, forming a zone of quiet culmination and pushing back the Neapolitan harmony.

The brighter is the appearance of the sound d as the last variant of the melodic move d-his-cis.

Movement in the range of the diminished third d-his acts as a harbinger of a recapitulation. Its coming was foreseen earlier, but re-bekar with complete inevitability and necessity attracts us to return. Here time measurement is combined with the expression of inevitability, predetermination, irreversibility of the course of time.

In the reprise, the role of II low is strengthened - the idea of humming in the volume of a reduced third is fixed in the cadence turnover. Therefore, a similar move in the "side game" sounds like a variation of the previous one.

As a result, another type of switching of functions arises - what was at the end is reintone into a thematic impulse.

So, turnover from low II and humming in the volume of a reduced third, starting as a moment of development, by the end of Adagio covers all three functions - thematic impulse, development and completion. This is reflected in its fundamentally important role for Adagio.

The code is a reflection of "development". As has been shown, the fifth recitative sounds in the lower voice. The appearance of the harmony of the dominant non-chord also corresponds to the principle of "reflection".

In the finale, the dialectic of the development of the two leitharmonies brings to life the dynamic forms of their manifestation. The second low as a development factor creates a turning point in the side game of the final. This sharply emphasized moment coincides with the culmination of not only this topic, but the entire exposition. Location II low in this case is exactly the middle of the exposure (32 + 32), that is, also a mathematically determined point.

Participation in the final round is an addition to the first theme of the final installment.

In the development of the finale, the role of II low becomes extremely significant - the Neapolitan harmony, fulfilling the function of development, already creates the tonality of II low from the subdominant - G-dur. This is the harmonious culmination of the whole finale.

In the code, there is a struggle between two leitharmonies for domination. The nonchord wins.

Let us now proceed to consider thematism and its development within the second part of "Lunar".

Allegretto assumes a soft and unhurried sound, we must not forget that the designation of the tempo refers to the quarters.

The contrast that Allegretto brings to the cycle is created by many factors: the eponymous, irreplaceable throughout the entire part of the major (Des-dur), the ostinate amphibrachic rhythm formula

quarter I half quarter I half. However, the grouping of three-quarter measures of four ties the Adagio to the Allegretto - here also the 4X3. The connection with the first part is strengthened by the motivational similarity of topics *.

It can be seen that the fifth stroke from V to I in Adagio is replaced in Allegretto by passing seconds. As an echo of Adagio in the second movement, there is a rotation with a diminished third.

If we take into account the mourning character of Adagio, its distant connections with the Marcia funebre of the Twelfth Sonata, attacca in the transition to Allegretto, then the second movement can be understood as a kind of cyclical trio in relation to the first movement. (Indeed, for a funeral march, a trio in the tonality of the major of the same name is typical.) This is also facilitated by the figurative solidity of the Allegretto, associated with the absence of figurative contrast. move associated with the "encircling" small seventh b-c. It is being prepared at the conclusion of the first section of the Allegretto and is finally established as a trio.

But because the minor seventh is played on the dominant bass, a large dominant chord is formed. Together with the echo of the stroke within the reduced third, they both become, as it were, major versions of the two leitharmonic and leitintonation formations of Adagio.

As a result, Allegretto, appearing without interruption in the role of a cyclic trio, contains those elements of intonation commonality that are typical for both parts of the cycle and for trios.

A retreat is needed here. The trio as part of a complex three-part form is the only section in non-cyclic, one-part forms that is genetically related to the suite (it is known that one of the sources of the complex three-part form is the alternation of 2 dances with a repetition of the first of them: for example, Minuet I, Minuet II , da capo), the only new topic in a non-cyclical form that arises not from “toggling”, but from “disabling” functions. (when switching functions, a new theme appears as a moment of development of the previous one (for example, a side part); when functions are turned off, the development of the previous one is completely completed, and the next theme appears as if anew) But parts of the sonata cycle also exist on the basis of the same principle. Therefore, the genetic and functional relationship between parts of a complex three-part and cyclic forms facilitates the possibility of their mutual reversibility.

Understanding Allegretto as a cyclic trio, and Presto as the otherness of Adagio allows us to interpret the entire three-part cycle "Lunar" as a combination of the functions of the cyclical and complex three-part forms. (There is actually no break between the second and third parts. The German researcher I. Mies writes: "It can be assumed that Beethoven forgot to write" attacca "between the second and third parts." He further gives a number of arguments in defense of this opinion).

The local functions of the three parts are the first movement, a trio and a dynamized reprise of a gigantic, complex three-part form. In other words, the ratio of all three parts of the "Lunar" is functionally similar to the ratio of sections of a three-part form with a contrasting trio.

In the light of this compositional idea, both the unique specificity of the "Lunar" cycle and the erroneous understanding of it as a cycle "without the first part" ** become apparent (See the editorial notes of A.B. Goldenweiser).

The proposed interpretation of the "Lunar" cycle explains its unique unity. It is also reflected in the "stingy" tonal plan of the sonata as a whole:

cis-H-fis-cis-cis-cis

cis-gis-fis - (G) -cis-cis-cis

In this tonal plan, first of all, fis-moll in the center of the shape of the outer parts should be noted. The appearance of the gis-moll finale in the exhibition is extremely refreshing. Such a natural - dominant - tonality arises quite late. But the stronger is its impact.

The unity of the sonata cycle of the cis-moll sonata is enhanced by a single rhythmic pulsation (which, by the way, is typical for classical samples of a complex three-part form). In footnotes to the sonata, A. B. Goldenweiser notes: “In the C sharp minor sonata, although perhaps with less literality than in the E flat major, one can also approximately establish a uniform pulsation throughout the sonata: the triplet the eighths of the first movement are, as it were, equal to the quarters of the second, and the whole bar of the second movement is equal to the half note of the finale. "

But the difference in tempo creates conditions for the opposite direction of a single rhythmic movement.

The expressive significance of the metro-rhythmic factors in Adagio was mentioned above. The difference between the extreme parts is reflected primarily in the above microstops of figuration: the fourth peon Presto is opposed to the dactyl of Adagio - a foot that contributes to the effect of a continuously storming movement (as, for example, in the development of the first movement of Beethoven's Fifth Piano Sonata or within the first movement of his Fifth Symphony ). In combination with the Presto tempo, this foot contributes to the creation of an image of forward-looking movement.

Rhythmic continuity, the gravitation towards the implementation of an individualized theme through general forms of melodic movement is one of the typical properties of many finals of sonatas and symphonies.

It is caused each time by the drama of this cycle, but still one can find a single guiding tendency - the desire to dissolve the personal in the universal, the mass, in other words, the desire for more generalized forms of expressive means. This is due, among other things, to the fact that the ending is the last part. The function of completion requires one form or another of generalization, reduction to a result. A visual-pictorial analogy is possible here. When moving away from the object of the image, when transferring a massive, collective (for example, a crowd of people), detailing gives way to wider strokes, more general contours. The desire to embody the image of a philosophically generalized nature also often leads to the continuity of movement in the final moments. Individual differences, thematic contrasts of the preceding parts dissolve in the vastness of the continuous movement of the finale. In the last part of "Lunar", the continuous movement is broken only twice on the edges of the reprise and the final section of the coda *. (Here dactylic three-bars of a higher order appear instead of the constantly acting choreic two-bars. This is also an echo of Adagio, in which a similar movement occurs before the dominant organ point. Further, a rhythmic and dynamic fracture creates an "explosion" - the third, decisive link in Beethoven's triad.) otherwise, it either captures the entire texture, or, like Adagio, coexists with the melody of the upper voice.

If the continuity of slow movement was associated with spiritual introspection, self-deepening, then the continuity of the rapid movement of the finale is explained by the psychological orientation outward, into the world around a person, - so in the mind of the artist, who embodies the idea of an active invasion of the personality into reality, the images of the latter take the form of some summary general background, coexisting with emotionally intense personal statements. The result is a rare combination of the final generalization with the proactive and active development inherent in the first parts.

If we start from Adagio and Presto "Lunar" as from the extreme poles in the expression of rhythmic continuity, then at the midpoint is the sphere of the lyrical moto perpetuo, embodied in the finale of Beethoven's Sonata d-moll. The movement in the range of the lyrical sixth of the first movement of "Lunar" here takes on a more individualized and lyrically accentuated form, embodied in the initial motif of the finale of the Seventeenth Sonata, in its first splash, giving birth to a boundless ocean.

In Lunar, the continuous movement of Presto is not so objective, its passionate romantic pathos arises from the familiar idea of angry protest, the activity of struggle.

As a result, the seeds of the future are ripening in the music of the cis-moll Sonata finale. Robert Schumann inherited the passion of expression of Beethoven's finals ("Lunar", "Appassionata"), as well as one of the forms of its expression - moto perpetuo. Let us recall the extreme parts of his fis-moll Sonata, the play "In der Nacht" and a number of similar examples.

Our analysis is complete. As far as possible, he proved the dramatic plan of the analyzed unique work postulated at the beginning of the article.

Leaving aside the version about the connection between the content of the sonata and the image of Juliet Guicciardi (dedication is only rarely connected with the artistic essence of the work) and any attempt at a plot interpretation of such a philosophical and generalized work, we will take the last step in revealing the main idea of the considered work.

In a large, significant piece of music, you can always see the features of the spiritual image of its creator. Of course, both time and social ideology. But both of these factors, like many others, are translated through the prism of the composer's individuality and do not exist outside of it.

The dialectic of Beethoven's triad reflects the personality traits of the composer. In this Man, the sharpness of uncompromising decisions, violent outbursts of a quarrelsome character with deep spiritual tenderness and cordiality coexist: an active nature, always looking for activity, with the contemplation of a philosopher.

Raised on the freedom-loving ideas of the late 18th century, Beethoven understood life as a struggle, a heroic act as overcoming constantly arising obstacles. High citizenship is combined in this great man with the most earthly and direct love for life, for the earth, for nature. Humor, no less than philosophical penetration, accompanies him in all the vicissitudes of his complex life. The ability to elevate the ordinary - the property of all great creative souls - in Beethoven is combined with courage and mighty willpower.

The ability to make quick decisions found direct expression in the third link of his drama. The very moment of the explosion is dialectical in essence - in it there is an instantaneous transition of quantity into quality. The accumulated, long-held tension leads to a contrasting shift in the state of mind. At the same time, the combination of actively effective volitional tension with external calmness is surprising and new in the history of musical embodiment. In this sense, Beethoven's pianissimos are especially expressive - a deep concentration of all spiritual forces, a powerful volitional restraint of bubbling internal energy. (An example of this is the "struggle" of two motives in the main part of "Appassionata" - the moment of structural fragmentation before the unifying and final explosion - passage sixteenth; the first the proposal of the main part from the Fifth Symphony before the explosion-motive). The next rhythmic and dynamic break creates an "explosion" - the third, decisive link in Beethoven's triad.

The peculiarity of the drama of the cis-moll sonata is, firstly, that between the state of concentrated tension and its release there is an intermediate stage - Allegretto. Secondly, in the very nature of concentration. Unlike all other cases, this stage arises as originally given) and, most importantly, combines many properties of Beethoven's spirit, philosophical severity, dynamic concentration with the expression of the deepest tenderness, a passionate desire for impossible happiness, active love. The image of the mourning procession of mankind, the movement of centuries is inextricably linked with a sense of personal sorrowful experience. What is primary, what is secondary? What exactly was the impetus for composing the sonata? This is not given to us to know ... But this is not essential. A genius of a human scale, you express yourself, embodies the universal. Any particular circumstance that prompted the creation of an artistic concept becomes only an external reason.

It was said about the role of Allegretto as a mediating link between concentration and "explosion" in the Sonata cis-moll and about the role of "Dante's formula". But in order for this formula to be involved in action, precisely those properties of Beethoven's human nature that have been described are necessary - his direct love for the earth and its joys, his humor, his ability to laugh and rejoice at the very fact ("I live" ). Allegretto combines elements of a minuet - not solemnly aristocratic, but folk - a minuet, which was danced in the open air, and a scherzo - a manifestation of humor and joyful laughter.

The most important aspects of Beethoven's spirit are condensed in Allegretto. Let us recall his major allegri of many sonatas, imbued with laughter, playing, and jokes. Let's call the 2nd, 4th, 6th, 9th sonatas ... Let us recall his minuets and scherzo of the same opuses.

It was only because Beethoven's music had such a powerful store of kindness and humor that it was possible that the short and outwardly modest Allegretto caused such a drastic shift. It was the opposition of mournful and tender concentration to the manifestation of love - simple and humane - that could give rise to the rebelliousness of the finale.

The incredible difficulty of performing AIIegretto stems from this. In this short moment of musical time, devoid of contrasts, dynamics, the richest life content, an essential aspect of Beethoven's worldview, is embodied.

The "explosion" in "Lunar" is a manifestation of noble anger: in the finale, the mental pain expressed in the first part is combined with a call to struggle, to overcome the conditions that give rise to this pain. And - this is the most important thing: the activity of Beethoven's spirit gives rise to faith in life, admiration for the beauty of the struggle for its rights - the highest joy available to man.

Our analysis was based on the idea of Presto as the other being of Adagio. But leaving aside all these factors, proceeding only from emotional and aesthetic comprehension and from psychological plausibility, we will come to the same. Great souls have great hatred - the other side of great love.

The usually dramatic first movement reflects life's conflicts in a stormy and dramatic aspect. The uniqueness of the drama of the cis-moll sonata lies in the fact that the response to the contradictions of reality, to the evil of the world is embodied in two aspects: the rebelliousness of the finale - the otherness of the mournful stiffness of Adagio, and both of them together - the otherness of the idea of good, a kind of proof from the opposite of its power and indestructibility ...

Thus, the sonata "Quasi una fantasia" reflects the dialectic of the great soul of its author in a single form, created only once.

But the dialectic of Beethoven's spirit, for all its exclusiveness, could take such a form only under the conditions of its time - from the crossing of socio-historical factors generated by the awakened forces of great world events, the philosophical awareness of the new tasks facing humanity and, finally, immanent laws evolution of musical and expressive means. The study of this trinity in connection with Beethoven is possible, of course, on the scale of his work as a whole. But within the framework of this article, you can still express a number of considerations on this matter.

In "Lunnaya" the ideological content of a panhuman scale is expressed. Connections with the past and the future are crossed in the sonata. Adagio throws a bridge to Bach, Presto to Schumann. The system of expressive means of the studied work connects the music of the 17th-19th centuries and remains creatively viable (which can be proved in a special analysis) in the 20th century. In other words, the sonata concentrates on the expression of that common, undying thing that unites the artistic thinking of such different eras. Therefore, Beethoven's creation once again proves the simple truth that brilliant music, reflecting contemporary reality, raises the problems it poses to the height of universal generalization, notes the eternal in today's (in the conventional sense of the word).

The ideas that worried the young Beethoven, which determined his worldview for the rest of his life, arose in him at an essential time. These were the years when the great liberating principles, postulates were not yet distorted by the course of history, when they appeared in their eagerly absorbing minds in their pure form. In light of this, it is extremely important that the world of ideas and the world of sounds were completely one for the composer. BV Asafiev wrote about this beautifully: “For him (Beethoven - VB), creative artistic construction is so closely connected with the senses of life and with the intensity of reactions-responses to the surrounding reality that there is no possibility and need to separate Beethoven - the master and the architect of music from Beethoven, a man who nervously reacted to impressions, which determined the tone and structure of his music by their strength. Beethoven's sonatas are therefore deeply relevant and vital. They are a laboratory in which the selection of life impressions took place in the sense of the response of the great artist to the feelings that outraged or delighted him and to the phenomena and events that elevated his thought. And since Beethoven developed high ideas about the rights and duties of a person, then, naturally, this sublime structure of mental life was reflected in music. "

Beethoven's musical genius was in close union with his ethical talent. The unity of ethical and aesthetic is the main condition for the emergence of creations of a universal scale. Not all major masters express in their work the unity of a conscious ethical principle and aesthetic perfection. The combination of the latter with a deep belief in the veracity of the great ideas reflected in the words "hug, millions" is the peculiarity of the inner world of Beethoven's music.

In the cis-moll sonata, the main components of the specific combination of conditions described above create a musical, ethical and philosophical image that is unique in its laconicism and generalization. It is impossible to name another work of a similar plan from Beethoven's sonatas. Dramatic sonatas (First, Fifth, Eighth, Twenty-third, Thirty-second) are united by a single line of stylistic development, have points of contact. The same can be said about the series of cheerful sonatas imbued with humor and direct love for life. In this case, we have before us a single phenomenon *.

Beethoven's truly universal artistic personality combines all types of expressiveness characteristic of his era: the richest spectra of lyrics, heroics, drama, epicness, humor, spontaneous cheerfulness, pastorality. All this, as if in focus, is reflected in a single triadic dramatic formula "Lunar". The ethical meaning of the sonata is as enduring as the aesthetic one. This work captures the quintessence of the history of human thought, passionate faith in goodness and life, captured in an accessible form. The whole immense philosophical depth of the sonata's content is conveyed by simple music going from heart to heart, music understandable to millions. Experience shows that "Lunar" captures the attention and imagination of those who remain indifferent to many other works of Beethoven. The impersonal is expressed through personal music itself. The extremely generalized becomes extremely generalized.

What you need to know about Beethoven, about the sufferings of Christ, about Mozart's opera and about romanticism in order to correctly understand one of the most famous works in the world, explains Vice-rector of the Humanitarian Institute of Television and Radio Broadcasting, Candidate of Arts Olga Khvoina.

In the vast repertoire of the world musical classics it is difficult, perhaps, to find a more famous work than Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata. You don't have to be a musician or even a great lover of classical music, so that, having heard its first sounds, you instantly recognize and easily name both the work and the author.

Sonata No. 14 or "Moonlight"

(in C sharp minor, op. 27, no. 2),

First part

Execution: Claudio Arrau

One clarification, however, is required: for an inexperienced listener, the recognizable music of the "Moonlight" sonata is exhausted. In reality, this is not the entire work, but only its first part. As befits a classical sonata, it also has a second and a third. So, enjoying the "Moonlight" sonata in the recording, it is worth listening to not one, but three tracks - only then will we know the "end of the story" and will be able to appreciate the whole composition.

To begin with, let's set ourselves a modest task. Focusing on the well-known first part, let's try to understand what this exciting, compelling music is fraught with.

The Moonlight Sonata was written and published in 1801 and is among the works that opened the 19th century in musical art. Having become popular immediately after its appearance, this work gave rise to many interpretations during the composer's lifetime.

Portrait of an Unknown Woman. The miniature, which belonged to Beethoven, is believed to depict Juliet Guicciardi. Around 1810

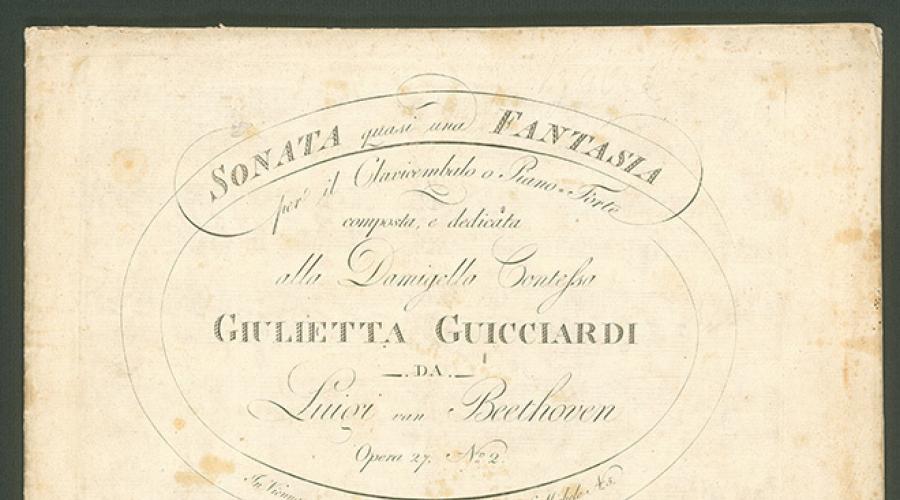

The dedication of the sonata to Juliet Guicciardi, a young aristocrat, student of Beethoven, whose marriage the musician in love dreamed of in vain during this period, fixed on the title page, prompted the audience to look for an expression of love experiences in the work.

The title page of the edition of Ludwig van Beethoven's Piano Sonata "In the Spirit of Fantasy" No. 14 (C sharp minor, op. 27, No. 2) with a dedication to Juliet Guicciardi. 1802 year

About a quarter of a century later, when European art was embraced by romantic longing, a contemporary of the composer, the writer Ludwig Rellstab, compared the sonata with a picture of a moonlit night on Lake Lucerne, describing this night landscape in the short story "Theodor" (1823) ;. It was thanks to Relshtab that the work known to professional musicians as Sonata No. 14, or, more precisely, Sonata in C sharp minor, Opus 27, No. 2, was given the poetic definition of "Moonlight" (Beethoven did not give this title to his work). In Rellshtab's text, which seems to have concentrated all the attributes of a romantic landscape (night, moon, lake, swans, mountains, ruins), the motif of “passionate unrequited love” sounds again: shaken by the wind, the strings of the aeolian harp are pitifully singing about her, filling with their mysterious sounds the whole space of the mystical night;

Having mentioned two very well-known versions of the interpretation of the sonata content, which are suggested by verbal sources (the author's dedication to Juliet Guicciardi, Rellshtab's definition of "Moonlight"), let us now turn to the expressive elements contained in the music itself, try to read and interpret the musical text.

Have you ever thought that the sounds, by which the whole world recognizes the "Moonlight" Sonata, are not a melody, but an accompaniment? Melody - seemingly the main element of musical speech, at least in the classical-romantic tradition (the avant-garde trends of 20th century music are not counted) - does not appear in the Moonlight Sonata right away: this happens in romances and songs when the sound of the instrument precedes the singer's introduction. But when a melody prepared in this way finally appears, our attention is completely focused on it. Now let's try to remember (maybe even sing) this melody. Surprisingly, we will not find in it its own melodic beauty (various turns, leaps at wide intervals, or smooth progressive movement). The melody of the Moonlight Sonata is constrained, squeezed into a narrow range, makes its way with difficulty, is not sung at all, and only sometimes sighs a little more freely. Its beginning is especially indicative. For some time, the melody cannot tear itself away from the original sound: before even slightly moving from its place, it is repeated six times. But it is this sixfold repetition that reveals the meaning of another expressive element - rhythm. The six first sounds of the melody reproduce the recognizable rhythmic formula twice - this is the rhythm of the funeral march.

Throughout the sonata, the initial rhythm formula will return repeatedly, with the insistence of thought that has taken possession of the hero's entire being. In the code of the first movement, the original motive will finally establish itself as the main musical idea, repeating over and over again in a gloomy low register: the validity of associations with the thought of death leaves no doubt.

Returning to the beginning of the melody and following its gradual development, we find another essential element. This is a motif of four closely connected, as if crossed sounds, pronounced twice as a tense exclamation and accentuated by dissonance in the accompaniment. To listeners of the 19th century, and even more so today, this melodic turn is not as familiar as the rhythm of the funeral march. However, in church music of the Baroque era (in German culture, represented primarily by the genius of Bach, whose works Beethoven knew from childhood), he was the most important musical symbol. This is one of the variants of the motif of the Cross - a symbol of the dying sufferings of Jesus.

Those who are familiar with the theory of music will be interested in learning about one more circumstance confirming that our guesses about the content of the first movement of the Moonlight Sonata are correct. For his 14th sonata, Beethoven chose the key in C sharp minor, which is rarely used in music. There are four sharps in this key. In German, "sharp" (a sign of raising the sound by a semitone) and "cross" are denoted by one word - Kreuz, and in the tracing of the sharp there is a resemblance to a cross - ♯. The fact that there are four sharps further reinforces the passionate symbolism.

Let us make a reservation again: working with such meanings was inherent in church music of the Baroque era, and Beethoven's sonata is a secular work and was written at a different time. However, even in the period of classicism, tonality remained tied to a certain range of content, as evidenced by contemporary musical treatises for Beethoven. As a rule, the characteristics given to tonalities in such treatises fixed the moods inherent in the art of the modern era, but did not break ties with the associations recorded in the previous era. Thus, one of Beethoven's older contemporaries, composer and theorist Justin Heinrich Knecht, believed that C sharp minor sounds "with an expression of despair." However, Beethoven, composing the first movement of the sonata, as we see, was not satisfied with a generalized idea of the character of tonality. The composer felt the need to turn directly to the attributes of a long-standing musical tradition (the motif of the Cross), which testifies to his focus on extremely serious topics - the Cross (as a destiny), suffering, death.

Autograph of Ludwig van Beethoven's Piano Sonata "In the Spirit of Fantasy" No. 14 (C sharp minor, op. 27, No. 2). 1801 year

Now let us turn to the beginning of the "Moonlight" sonata - to those sounds, familiar to all, that catch our attention even before the melody appears. The backing line is made up of continuously repeating three-tone figures that resonate with deep organ basses. The initial prototype of such a sound is the busting of strings (lyre, harp, lute, guitar), the birth of music, listening to it. It is easy to feel how the non-stop, even movement (from the beginning to the end of the first movement of the sonata, it does not interrupt for a moment) creates a meditative, almost hypnotic state of detachment from everything external, and the slowly, gradually descending bass enhances the effect of withdrawing into oneself. Returning to the picture drawn in Rellshtab's short story, let us once again recall the image of the aeolian harp: in the sounds made by the strings only due to the blows of the wind, mystically-minded listeners often tried to grasp the secret, prophetic, fateful meaning.

To researchers of theatrical music of the 18th century, the type of accompaniment, reminiscent of the beginning of the Moonlight Sonata, is also known as ombra (from Italian - "shadow"). For many decades, in opera performances, such sounds accompanied the appearance of spirits, ghosts, mysterious messengers of the underworld, more broadly - reflections on death. It is reliably known that when creating the sonata, Beethoven was inspired by a very specific opera scene. In the sketchbook, where the first sketches of the future masterpiece were recorded, the composer wrote out a fragment from Mozart's opera Don Giovanni. This is a short but very important episode - the death of the Commander, who was wounded during a duel with Don Juan. In addition to the aforementioned characters, Don Juan's servant Leporello participates in the scene, so that a tercet is formed. The heroes sing at the same time, but each about his own: the Commander says goodbye to life, Don Juan is full of remorse, shocked Leporello abruptly comments on what is happening. Each of the characters not only has their own lyrics, but also their own melody. Their remarks are united into a single whole by the sound of the orchestra, which not only accompanies the singers, but, stopping the external action, fixes the viewer's attention at the moment when life teeters on the brink of nothingness: measured, "dripping" sounds count the last moments separating the Commander from death. The end of the episode is accompanied by the remarks "[The Commander] is dying" and "The month is completely hidden behind the clouds." Beethoven will repeat the sound of the orchestra from this Mozart scene almost literally at the beginning of the Moonlight Sonata.

First page of Ludwig van Beethoven's letter to brothers Karl and Johann. October 6, 1802

There are more than enough analogies. But is it possible to understand why the composer, who barely crossed the threshold of his 30th birthday in 1801, was so deeply, so really worried about the topic of death? The answer to this question is contained in a document whose text is no less poignant than the music of the Moonlight Sonata. This is the so-called "Heiligenstadt testament". It was found after the death of Beethoven in 1827, but was written in October 1802, about a year after the creation of the Moonlight Sonata.

In fact, the "Heiligenstadt Testament" is an extended letter from his death. Beethoven addressed it to his two brothers, indeed giving a few lines to the inheritance orders. The rest is an extremely sincere story about the suffering he experienced, addressed to all contemporaries, and possibly to descendants, in which the composer several times mentions the desire to die, expressing at the same time the determination to overcome these moods.

At the time of the creation of the will, Beethoven was in the suburb of Vienna, Heiligenstadt, undergoing treatment for an illness that had tormented him for about six years. Not everyone knows that the first signs of hearing loss appeared in Beethoven not in his mature years, but in the prime of his youth, at the age of 27. By that time, the composer's musical genius had already been appreciated, he was received in the best houses in Vienna, he was patronized by patrons of art, he won the hearts of ladies. The illness was perceived by Beethoven as the collapse of all hopes. Almost more painful was the fear of opening up to people, so natural for a young, proud, proud person. Fear of discovering professional inconsistency, fear of ridicule or, on the contrary, manifestations of pity, forced Beethoven to limit communication and lead a lonely life. But even reproaches for unsociability hurt him painfully with their injustice.

All this complex range of experiences was reflected in the "Heiligenstadt Testament", which recorded a turning point in the composer's mood. After several years of struggling with illness, Beethoven realizes that hopes for a cure are in vain, and rushes between despair and a stoic acceptance of his fate. However, in suffering, he early gains wisdom. Reflecting on providence, deity, art ("only it ... it held me back"), the composer comes to the conclusion that it is impossible to die without fully realizing his talent.

In his mature years, Beethoven will come to the idea that the best of people through suffering find joy. The Moonlight Sonata was written at a time when this milestone had not yet been passed.

But in the history of art, she has become one of the best examples of how beauty can be born out of suffering.

Sonata No. 14 or "Moonlight"

(in C sharp minor, op. 27, no. 2)

Execution: Claudio Arrau

The sonata cycle of the fourteenth piano sonata consists of three parts. Each of them reveals one feeling in the richness of its gradations. The meditative state of the first movement is replaced by a poetic, noble minuet. The finale is a "stormy bubbling of emotions", a tragic impulse ... it amazes with its irrepressible energy and drama.

The figurative meaning of the finale of the "Moonlight" sonata is in the grandiose battle of emotion and will, in the great anger of the soul, which fails to master its passions. Not a trace of the rapturous and disturbing dreaminess of the first part and the deceptive illusion of the second has remained. But passion and suffering dug into the soul with a force never experienced before.

It could also be called a "sonata of the alley", because, according to legend, it was painted in a garden, in a semi-burger-semi-rural environment, which the young composer liked so much "(E. Herriot. Life of L. V. Beethoven).

A. Rubinstein vigorously protested against the epithet "lunar" given by Ludwig Relstab. He wrote that moonlight requires something dreamy and melancholic, tenderly luminous in musical expression. But the first movement of the cis-moll sonata is tragic from the first to the last note, the last is stormy, passionate, something opposite to the light is expressed in it. Only the second part can be interpreted as moonlight.

“There is more suffering and anger than love in the sonata; the music of the sonata is dark and fiery ”- considers R. Rolland.

B. Asafiev wrote enthusiastically about the music of the sonata: “The emotional tone of this sonata is filled with strength and romantic pathos. The music, nervous and agitated, now flares up with a bright flame, then dies in agonizing despair. The melody sings, crying. The deep cordiality inherent in the described sonata makes it one of the most beloved and accessible. It is difficult not to succumb to the influence of such sincere music - the expression of direct feelings. "

L. Beethoven "Moonlight Sonata"

Today there is hardly a person who has never heard the "Moonlight Sonata" Ludwig van Beethoven , because this is one of the most famous and beloved works in the history of musical culture. Such a beautiful and poetic name was given to the work by the music critic Ludwig Rellshtab after the death of the composer. To be more precise, not the entire work, but only its first part.

History of creation Moonlight Sonata Beethoven, the content of the work and many interesting facts read on our page.

History of creation

If about another most popular work of Beethoven bagatelle difficulties arise, when trying to find out exactly who it was dedicated to, then everything is extremely simple. Piano Sonata No.14 in C sharp minor, written in 1800-1801, was dedicated to Juliet Guicciardi. The maestro was in love with her and dreamed of getting married.

It is worth noting that during this period the composer began to increasingly feel a deterioration in his hearing, but he was still popular in Vienna and continued to give lessons in aristocratic circles. For the first time about this girl, his student, "who loves me and is loved by me," he wrote in November 1801 to Franz Wegeler. The 17-year-old Countess Juliet Guicciardi and met in late 1800. Beethoven taught her the art of music, and did not even take money for it. In gratitude, the girl sewed his shirts. It seemed that happiness awaits them, because their feelings are mutual. However, Beethoven's plans were not destined to come true: the young countess preferred him a more noble person, the composer Wenzel Gallenberg.

The loss of a beloved woman, increasing deafness, collapsed creative plans - all this fell on the unfortunate Beethoven. And the sonata, which the composer began to write in an atmosphere of inspiring happiness and quivering hope, ended in anger and rage.

It is known that it was in 1802 that the composer wrote the very "Heiligenstadt testament". In this document, desperate thoughts of impending deafness and unrequited, deceived love merged together.

Surprisingly, the name "Lunar" was firmly entrenched in the sonata thanks to the Berlin poet, who compared the first part of the work with the beautiful landscape of Lake Lucerne on a moonlit night. Curiously, many composers and music critics opposed such a name. A. Rubinstein noted that the first movement of the sonata is deeply tragic and most likely it shows the sky with thick clouds, but not the moonlight, which, in theory, should express dreams and tenderness. Only the second part of the work can be called a moonlight with a stretch. Critic Alexander Maykapar said that the sonata does not contain the same "moonlight" that Rellshtab spoke about. Moreover, he agreed with the statement of Hector Berlioz that the first part is more reminiscent of a "sunny day" than a night. Despite the protests of critics, it was this name that was assigned to the work.

The composer himself gave his work the name "sonata in the spirit of fantasy." This is due to the fact that the usual form for this work was broken and the parts changed their sequence. Instead of the usual "fast-slow-fast", the sonata develops from a slow movement to a more mobile one.

Interesting Facts

- It is known that only two titles of Beethoven's sonatas belong to the composer himself - these are “ Pathetic "And" Farewell ".

- The author himself noted that the first part of "Lunar" requires the most delicate performance from the musician.

- The second movement of the sonata is usually compared with the dances of the elves from Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream.

- All three parts of the sonata are united by the finest motivational work: the second motive of the main theme from the first part sounds in the first theme of the second part. In addition, many of the most expressive elements from the first part are reflected and developed in the third.

- It is curious that there are many variants of the plot interpretation of the sonata. It was the image of Relshtab that received the greatest popularity.

- In addition, an American jewelry company has released a stunning natural pearl necklace called the Moonlight Sonata. How do you like coffee with such a poetic name? It is offered to its visitors by a well-known foreign company. And finally, even animals are sometimes given such nicknames. Thus, a stallion bred in America received such an unusual and beautiful nickname as "Moonlight Sonata".

- Some researchers of his work believe that in this work Beethoven anticipated the later work of romantic composers and call the sonata the first nocturne.

- Famous composer Franz Liszt called the second movement of the sonata "A Flower in the Abyss". Indeed, some listeners think that the introduction is very similar to a barely opened bud, while the second part is the flowering itself.

- The name "Moonlight Sonata" was so popular that it was sometimes applied to things completely far from music. For example, this phrase, which is familiar and familiar to every musician, was the code for the 1945 air raid on Coventry (England) by the German invaders.

In the "Moonlight" Sonata, all the features of composition and drama depend on the poetic concept. In the center of the work is a spiritual drama, under the influence of which the mood changes from mournful self-absorption, shackled by sadness of reflection to violent activity. It is in the finale that the very open conflict arises, in fact, for its display, it was necessary to rearrange the parts in places to enhance the effect and drama.

First part- lyrical, it is completely focused on the feelings and thoughts of the composer. Researchers note that the manner in which Beethoven reveals this tragic image brings this part of the sonata closer to Bach's choral preludes. Listen to the first part, what image did Beethoven want to convey to the public? Of course, the lyrics, but they are not light, but slightly overshadowed by sorrow. Maybe these are the composer's thoughts about his unfulfilled feelings? Listeners, as if for a moment, plunge into the dream world of another person.

The first part is presented in a prelude-improvisational manner. It is noteworthy that in this whole part, only one image dominates, but such a strong and laconic one that does not require any explanations, only concentration on oneself. The main melody can be called acutely expressive. It may seem that it is quite simple, but it is not. The melody is complex in terms of intonation. It is noteworthy that this version of the first part is very different from all its other first parts, since there are no sharp contrasts, transitions, only a calm and unhurried flow of thought.

However, let us return to the image of the first part, its mournful detachment is only a temporary state. The incredibly intense harmonic movement, the renewal of the melody itself, speaks of an active inner life. Can Beethoven be in a state of grief and reminiscing for so long? The rebellious spirit must still make itself felt and throw out all the raging feelings out.

The next part is rather small and is built on light intonations, as well as the play of light and shadow. What is hidden behind this music? Perhaps the composer wanted to talk about the changes that took place in his life thanks to his acquaintance with a beautiful girl. Without a doubt, during this period - true love, sincere and light, the composer was happy. But this happiness did not last long at all, because the second part of the sonata is perceived as a small respite in order to enhance the effect of the finale, which burst in with all its storm of feelings. It is in this part that emotions are incredibly high. It is noteworthy that the thematic material of the finale is indirectly connected with the first part. What emotions does this music remind? Of course, there is no more suffering and sorrow here. It is an outburst of anger that covers up all other emotions and feelings. Only at the very end, in the code, the entire experienced drama is pushed back into the depths by an incredible effort of will. And this is already very similar to Beethoven himself. In a swift, passionate impulse, menacing, mournful, agitated intonations sweep through. The whole range of emotions of the human soul, which has experienced such a heavy shock. It is safe to say that a real drama unfolds in front of the audience.

Interpretations