Man is the main character of aitmatov in his works. Works of Chingiz Aitmatov

The novel "Plakha" sounds like a warning. The action takes place in Central Asia, in the Moyunkum steppe. The novel begins with the theme of wolves. Their natural habitat is dying, dying through the fault of a man who breaks into the savannah like a predator, like a criminal. Wolves are not just humanized in the work, as has always happened with the images of animals in literature. Based on the author's intention, they are endowed with that nobility, that high moral strength, which people who opposed them are deprived of. Boston, one of the main characters in the novel, takes responsibility for both those who shot saigas from helicopters and for Bazarbai, who carried away the cubs.

The writer develops in detail the storyline of Boston in the novel, which embodies the moral norm, that natural humanity, which is violated and desecrated by Bazarbay. The she-wolf carries away the son of Boston. Boston kills his son, a she-wolf, Bazarbai. The origins of this murder are in the disturbance of the existing equilibrium. Having shed blood three times, Boston realizes: he killed himself with these three shots. The beginning of this catastrophe was there, in the Moyunkum savanna, where, according to someone's plan, sealed with authoritative seals, the natural course of life was destroyed.

Aitmatov sees the depicted situation from two sides, as if on two levels. And as a result of gross mistakes in the economic, economic field. And as a manifestation of both ecological and moral crisis of universal human significance. The storyline of the wolves and Boston develops in parallel with the line of Avdiy Kallistratov. This is the second semantic and plot center of the novel. The former seminarian wants and hopes with his moral influence, his high spirituality and dedication to turn these fallen people, drug dealers, from their criminal business and criminal path. The writer gives his own interpretation of the legend of Jesus Christ and compares the story of Obadiah with the story of Christ who sacrificed himself to atone for the sins of mankind. Obadiah goes to self-sacrifice for the salvation of human souls. But, apparently, times have changed. The death of the crucified, like Christ, Obadiah, is not able to atone for human sins. Humanity is so mired in vices and crimes that the victim can no longer return anyone to the path of Good. The idea leading Obadiah to the chopping block is not approved, but tested for vitality in today's world, for real social effectiveness. The writer's conclusions are pessimistic.

Ch. Aitmatov's novel "Plakha" sounded in the 1980s as a distress signal, as a warning to mankind, who forgets that it lives in the natural world, belongs to it, that the destruction of nature, neglect of its laws and its primordial balance threatens innumerable disasters both to the individual and to the entire human community. The writer seeks to comprehend environmental problems as problems of the human soul. If humanity does not heed, does not stop in its ever-accelerating movement to the edge, to the abyss, a catastrophe awaits it.

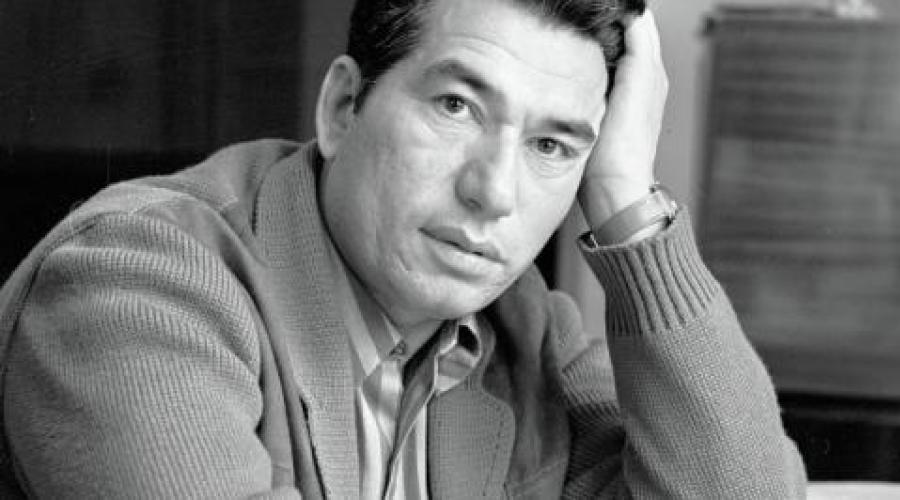

Chingiz Aitmatov was born in 1928 in the valley of the Talas River, in the Sheker village of the Kirov region of the Kyrgyz SSR. The working biography of the future writer began during the Great Patriotic War. “Now I can't believe it myself,” Chingiz Aitmatov recalled, “at the age of fourteen I already worked as a secretary of ail councils. At the age of fourteen I had to solve issues concerning the most diverse aspects of life in a large village, and even in wartime. "

Hero of Socialist Labor (1978), Academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz SSR, laureate of the State. Prize (1968, 1977, 1983), laureate of the Lenin Prize in 1963, holder of the Order of Friendship (1998), adopted from the hands of Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin, ex-editor-in-chief of the journal "Foreign Literature". In 1990 he was appointed Ambassador of the USSR in Luxembourg, where he currently resides as the Ambassador of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan.

For a long time and persistently he searched for his themes, his heroes, his own style of storytelling. And- found them. Its heroes are ordinary Soviet workers who firmly believe in the bright, good beginnings of life created with their most active participation. “A bright, human life”, people are pure and honest, open to everything good in the world, reliable in business, lofty in aspirations, direct and frank in relationships with people. In the stories of "Jamil" (1958). “My poplar in a red scarf” (1961), “The first teacher” (1962) the harmony, purity and beauty of their souls and thoughts are symbolized by the melodious poplars, spring white swans on Lake Issyk-Kul and this blue lake itself in a yellow collar of sandy shores and gray sand and white necklace of mountain peaks.

With their sincerity and straightforwardness, the heroes found by the writer, as it were, suggested to him the manner of storytelling - agitated, slightly upbeat, tensely confidential and, often, confessional - in the first person, from the "I".

From the very first works, Ch. customs (laws of adat), or predators, power-hungry despots, lead bureaucrats, like Segizbayev in the story “Farewell, Gyulsary!”, with tyrants and scoundrels like Oroe-kul in the “White steamer”.

In "Jamila" and "The First Teacher" the writer managed to capture and capture the bright pieces of life, glowing with joy and beauty, despite their inner drama penetrating them. But those were precisely the pieces, episodes of life, about which he spoke sublimely, to use the famous Lenin's word, spiritually uplifting, himself, filled with joy and happiness, as the artist who sets the tone in Jamila and The First Teacher is filled with them. (This is how M. Gorky once talked about his life in "Tales of Italy.") For this, critics called them romantic, despite a solid realistic basis, as the writer's talent developed, deepening it into a life that subjugated all romantic elements.

The writer captures life more and more deeply, trying to penetrate its innermost secrets, without avoiding the most pressing issues generated by the twentieth century. The controversial story "Mother's Field" (1965) marked the transition of the writer to the most severe realism, which reached its maturity in the stories "Farewell, Gyulsary!" (1966). The White Steamer (1970). “Early Cranes” (1975), in the novel “Storm Stop (And the Day Lasts More Than a Century)” (1980). No longer separate pieces, layers, layers of life, but the whole world begins to be seen in the paintings created by the writer, the real world with all its past, present, future, a world that is not even limited by the Earth. Joys, sorrows, bright and dark possibilities of our planet in its geographic integrity and social fragmentation paint the writer's work in new colors. Aitmatov possesses strategic thinking, he is interested in ideas of a planetary scale. If in his early works, for example, in the story "The First Teacher", the writer focused mainly on the originality of Kyrgyz love, life, culture and, as they say now, mentality, then in the novels "Plakha" and "And the day lasts longer than a century", which had a resounding success in the late 70s - 80s, he already showed himself as a citizen of the globe. Raised, as they used to say, global issues. For example, he openly declared that drug addiction is a terrible scourge. He allowed himself to be raised, because before him no one was allowed. After all, as you know, drug addiction, like sex, was not in the USSR.

“Much wisdom gives birth to sorrow,” said the ancients. Chingiz Aitmatov did not escape this either. Starting with the story “Farewell, Gyulsary!”, For all, I would say, the militantly asserting pathos of his work, it shakes with the sharp drama of the collisions of life taken, stunning turns in the fate of the heroes, sometimes tragic fate in the most sublime meaning of these words, when she herself death serves the elevation of a person, the awakening of the resources of good hidden in him.

Naturally, the principles of storytelling also become more complex. The story from the author is sometimes combined by means of improperly direct speech with the hero's confession, which often turns into an internal monologue. The hero's inner monologue just as imperceptibly pours into the author's speech. Reality is captured in the unity of its present, its roots and its future. The role of folklore elements is sharply increasing. Following the lyrical songs that often sound in the first stories, the author more and more freely intersperses folk legends, reminiscences from Manas and other folk epic tales into the fabric of his works. In the story "The White Steamer", the paintings of modern life, like multicolored carpet patterns, are woven on the canvas of the expanded Kyrgyz legend about the mother Olenikha, and are woven in such a way that sometimes it is difficult to understand where the basis is and where the drawing is. In addition, the revitalization, humanization (anthropomorphism) of nature is so organic that a person is perceived as an inseparable part of it, in turn, nature is inseparable from a person. In the story Piebald Dog Running by the Edge of the Sea (1977), in the novel Burannyi Polustanok, the artistic palette is also enriched by unobtrusive submission to the realism (realism of the purest test) of myth, legends, and “legends of deep antiquity”. These and other folklore elements always carry a polysemantic meaning, they are perceived either as symbols, or as allegories, or as psychological parallels, giving the works a diversity and depth, the content - polysemy, and the image is stereoscopic. The writer's work as a whole begins to be perceived as an epic legend about the world and man in one of the most magnificent eras - a legend created by one of its most active and passionate figures.

Chingiz Aitmatov sees the main justification for the development of mankind for millions of years, its centuries-old history, captured in myths and legends, a guarantee of its bright future. Life - human existence - freedom - revolution - building socialism - peace - the future of mankind - these are the steps that form a single and unique ladder along which the real creator and master of life, Man of Mankind, rises “all ahead! and higher!". He, the main character of Chingiz Aitmatov, is personally responsible for everything that was, is and will be, that can happen to people, the Earth, the Universe. He - a man of action and a man of intense thought - is intently examining his past in order to prevent miscalculation on the difficult path paved by all of humanity. He is looking anxiously into the future. This is the scale that guides the writer both in his approach to the modern world and in portraying his hero, comprehending them in all their polysemy.

A poignant work, written really with the blood of the heart, the novel "Burannyi polustanok" gave rise to a variety of, in many respects, diverging opinions. The discussion around him continues. Some believe that the temporal ambiguity of the image of the "semolina mouth" can give rise to misinterpretation. Others say that the symbol called "Parity" in the novel and bearing the entire cosmic line in the work is made up of contradictory principles and therefore cannot be accepted unconditionally, as well as the very solution of the main problem associated with it. In addition, others add, both the legend of the “mankurt” and the space fresco created by purely publicistic means are not very organically welded to the main - strictly realistic - part of the narrative. One can agree or disagree with such opinions, but one cannot but admit the main thing: the novel “Storm Stop”, permeated, according to Mustai Karim, with “pain and immeasurable optimism, immeasurable faith in man ...”, will hardly leave anyone indifferent ...

The writer managed to convincingly show the richest spiritual world of an ordinary person who has his own opinion on the most difficult problems of human existence. Through the eyes of its protagonist our era itself looks at us with its victories and defeats, its bitterness and joys, difficult problems and bright hopes.

New novel - "Brand of Cassandra", published in "Znamya" in 1994. Even more restless, but restless in its own way, "in the Aitmatov way." It would seem that people in the vast expanses of the CIS are fighting, stealing money in huge quantities, doing other obscenities - just write about it. However, Aitmatov, apparently, is not able to consider all kinds of particulars under his feet. His gaze is still directed to the Earth from top to bottom, covering it entirely.

It is no coincidence that the main character, the monk Philotheus, flies around the Earth in an orbital station: so you can better see her, unfortunate, better. Filofey was not always like that, before he was a scientist Andrei Andreevich Kryltsov, who specialized in breeding artificial people, "iksrods", in the womb, so to speak, of free experimenters, that is, female prisoners. Then, shortly before declaring himself a monk, the scientist found out that not only is this unrighteous business, but embryos also refuse to be born, in which evil reigns. This was the decision of nature: to protect itself from blood-sucking humanity, let it die out. Isn't it a mild Apocalypse?

Read also:

|

Chingiz Torekulovich Aitmatov is a wonderful modern writer. Working in literature for over forty years, he was able to vividly and truthfully reflect the difficult and heroic moments of our history. The writer is still full of creative plans, working on another novel.

Aitmatov was born in 1928 in the remote village of Sheker in Kyrgyzstan. In 1937, his father, a prominent party worker, was illegally repressed. It was then that Aitmatov received a lesson in honor: "When asked" whose son are you? " it is necessary, without lowering his head, looking straight into the eyes of people, to call the name of his father. This was the order of my grandmother, my father's mother. " A long-standing lesson of honor became the principle of life and later - of creativity.

The writer makes extensive use of mythology, even a fairy tale. Aitmatov's mythology is rather peculiar. Modern mythologism is not only the poetics of myth, but also the perception of the world behind it, which includes a complex set of ideological and artistic views.

The myth is also present in his "White Steamer". The whole life of the myth in the story is realistically correlated with reality: the old grandfather tells his grandson a fairy tale, and the grandson, a little boy, as is typical for children, believed in its truth. Aitmatov, gradually revealing to us the inner world of his hero, shows how in his rich poetic imagination, constantly creating his little fairy tales (with binoculars, stones, flowers, briefcase), a "fairy tale" (as he calls the myth) about the Horned Mother can also live deer. The appearance of living marals in the local reserve supports the legend of the saving Deer living in the boy's mind.

The second deep plan of the life of a myth is born outside the narrative, already in our, reader's mind: nature is the mother of everything on earth and man too: forgetting this truth leads to fatal consequences, most of all fraught with deep moral losses, i.e. myth plays the role of artistic metamorphosis to express this thought of the writer.

Ch.Aitmatov deeply and correctly depicted the undivided human consciousness, was able to enter it. The realist writer sets himself the task of recreating the peculiar inner world of the patriarchal Nivkh man. The artist consistently reveals a new national world for himself, widely using the Nivkh geographical, ethnic, folklore material. Ch. Aitmatov builds his story in his usual epic vein - again widely using repetitions, refrains, again applying the technique of the author's voice in the heroes' zones, the main nerve is still the stream of consciousness, allowing to reveal that subtle psychologism that puts this epic legend in a number of contemporary works. And realistic signs not only of everyday life (clothes, hunting equipment, dugout boat), but also of time, are given, albeit sparingly, but accurately and clearly, in order to recreate a certain historical moment in the life of the Nivkhs.

Ch. Aitmatov tells the story as a legend, but we still perceive it as a story. This is because, setting himself the task of creating a legend, a myth, Aitmatov deprives the narrative of the conventions inherent in myth and, plunging us into the world of reality, thereby destroys the myth.

The very action of the works, the actions of the heroes, the movement of the plot are devoid of mythical miracles. To Ch. Aitmatov, the truth is fundamentally important. This is his position, his literary credo.

In the novel “And the day lasts longer than a century”, there are, as it were, several spaces: Buranny half-station, Sary-Ozekov, a country, a planet, near-earth and deep space. It's like

one coordinate axis, the second temporal: the distant past, the present and an almost fantastic future are linked together. Each space has time, they are all interconnected.

From these interconnections, which arise due to a complex compositional solution, metaphors and associative images of the novel are born, giving depth and expressiveness to the writer's artistic generalizations. At the very beginning of the novel, the switchman Edigei divorces all three

time; the letter will go to the future at the Sary-Ozek cosmodrome, Edigei himself will remain in the present, and his thoughts will be carried away into the past. From this moment on, the categories of time will exist in different worlds and develop in parallel. They will unite, they will close only in the finale of the novel in the terrible picture of the apocalypse. “The sky collapsed on your head, opening up in clouds of boiling fire and smoke ... Man, camel, dog - these simple creatures, maddened, ran away. Terrified, they ran together, fearing to part with each other, they ran across the steppe, mercilessly

illuminated by gigantic flashes of fire ... "

The meeting place of times was the ancient ancestral cemetery Ana-Beyit, "which arose at the place of the death of a mother, killed by the hand of a mankurt son, disfigured by medieval Ruanzhuans.

The new barbarians built a cosmodrome on the ancestral cemetery, where, in the thickness of the earth, in the ashes of their ancestors, for the time being, robotic missiles lurked, closing the seemingly broken connection of times on a signal from the future, the forces of evil of the distant past, incredibly cruel with point of view of the present. So in the novel by Ch. Aitmatov, images of space - time, heroes, thoughts and feelings are intertwined and a surprisingly harmonious unity is born, which is especially necessary in our century not only because of the invasion of scientific and technical achievements into the field of fiction, but rather because it is contradictory and disharmonious the world we live in.

The originality of the myth lies in the fact that the past is closely intertwined with the present, which means that people of our time turn to the past, while Ch. Aitmatov's past is a myth. Therefore, the writer reveals the problems of modernity in myths.

Aitmatov is interested in ideas on a planetary scale. If in the story “The First Teacher” the writer focused mainly on the originality of Kyrgyz love, life, culture and, as they say now, mentality, then in the novels “Plakha” and “And the day lasts longer than a century”, he showed himself as a citizen of the globe. It raises global issues. The writer openly stated that drug addiction is a terrible scourge. And in the USSR at that time there was no drug addiction, like sex. Aitmatov allowed himself to raise this topic, because before him no one was allowed.

Aitmatov's narrative principles become more complicated. The story from the author is sometimes combined by means of improperly direct speech with the hero's confession, which often turns into an internal monologue. The hero's inner monologue turns into the author's thoughts. The role of folklore elements is increasing. Following the lyrical songs that were used in early stories, the author more and more freely intersperses folk legends into the fabric of his works.

Pictures of modern life in the story "The White Steamer" are presented against the background of the Kyrgyz legend about the Mother Deer, and it is even difficult to understand where is the basis and where is the drawing. In addition, the personification of nature is organic, and a person is perceived as an integral part of it. Nature, in turn, is inseparable from man.

The writer's work as a whole begins to be perceived as an epic legend about the world and man in one of the most majestic eras - a legend created by one of its most active and passionate figures.

Life - human existence - freedom - revolution - building socialism - peace - the future of mankind - these are the steps that form a single and unique ladder, according to

which the real creator and master of life, Man of Mankind, rises “all ahead! and higher!". He, the main character of Chingiz Aitmatov, is personally responsible for everything that was, is and will be, that can happen to people, the Earth, the Universe. He - a man of action and a man of intense thought - is intently examining his past in order to prevent miscalculation on the difficult path paved by all of humanity. He is looking anxiously into the future. Such is the scale by which

the writer is guided both in the approach to the modern world and in the portrayal of his hero, comprehending them in all their polysemy.

"Burannyi polustanok" - the first novel by Ch. Aitmatov - is a significant phenomenon in our literature. In this work those creative findings and ideas that "appeared" in the stories found their development; which brought the writer not only all-Union, but also world fame. A distinctive feature is an epic orientation ”. Three storylines that develop in parallel and intersect only once, but their relationship is carried out throughout the entire narrative. The breadth and spatiality of the depicted world. The category of time reinforces the overall epic thrust of the piece. The interdependence of the present, past, future creates the volumetric integrity of the work. Time is epic. The character of the protagonist is epic and gets caught up in the most important events taking place in the world. The pathos of the novel is in the affirmation of the harmonious synthesis of man and society, the triumph of reason and peace. The essential features of the epic novel - the spatiality and volume of time and main plot lines, the epic character and conflict, the author's own worldview - are present in the novel in organic unity.

All this constitutes the originality of Ch.Aitmatov's work.

The main actions in the novel "Plakha" take place on the endless expanses of the Mayunkum savanna, the Issykul region. The main characters: Avdiy Kallistratov, messengers for the hash, Oberkandal and Boston Urkunchiev. The main artistic arsenal for solving the problem of freedom-non-freedom: techniques that reveal psychology: internal monologues, dialogues, dreams and visions; images-symbols, antithesis, comparison, portrait.

Avdiy Kallistratov is one of the most important links in the chain of heroes of the Mayunkum chapters of Plakhi. As the son of a deacon, he entered a theological seminary and was listed there “... as a promising one ...” However, two years later he was expelled for heresy. The fact is (and these were the first steps of the hero as a free person) that Obadiah, believing “... that traditional religions ... are hopelessly outdated ...” because of his dogmatism and obduracy, puts forward his own version “.. . development in time

categories of God depending on the historical development of mankind. " The character is sure that an ordinary person can communicate with the Lord without intermediaries, that is, without priests, and the church could not forgive this. In order to "... return the lost youth to the bosom of the church ..." a bishop or, as he was called, the Coordinator Father, comes to the seminary. During a conversation with him, Obadiah "... felt in him the power that in every human deed, guarding the canons of faith, first of all observes its own interests." Nevertheless, the seminarian is frank about the fact that

dreams of "... overcoming the eternal stagnation, emancipation from dogmatism, giving the human spirit freedom in knowing God as the highest essence of one's own being." In other ways, the “spirit of freedom” should govern a person, including his desire to know God.

Contrary to the assurances of the Coordinator's Father that the main reason for the "rebellion" of the seminarian is extremism characteristic of youth, Obadiah does not renounce his views. In the "sermon" of the Father

The coordinator sounded a thought that became reality in the further tragic life of Kallistratov:

who doubts the fundamental teachings ... and you will still pay ... ”Obadiah's conclusions were unsettled, debatable, but even such freedom of thought, official theology did not forgive him, expelling him from its midst.

After being expelled from the theological seminary, Avdiy works as a freelance employee of the Komsomol newspaper, the editorial board of which was interested in such a person, since the former

the seminarian was a kind of anti-religious propaganda. In addition, the hero's articles differed in unusual topics, which aroused the interest of readers. Obadiah pursued the goal “... to acquaint the reader with the circle of thoughts for which, in fact, he was expelled

from the theological seminary. " The character himself says about it this way: “I have long been tormented by the thought - to find the paths I have found to the minds and hearts of my peers. I saw my vocation in teaching good. ”In this aspiration of the hero Ch. Aitmatov can be compared with Bulgakov's Master

the novel about Pilate also advocated the most humane human qualities, defending the freedom of the individual. Like the hero of “The Master and Margarita”, Avdiy cannot publish his “alarm” articles on drug addiction, since “... higher authorities ...”, deprived of truth, and therefore freedom, not wanting to damage the country's prestige with this problem, do not let them go to print. “Fortunately and unhappily for his own, Avdiy Kallistratov was free from the burden of such ... hidden fear ...” The hero's desire to tell the truth, no matter how bitter it may be, emphasizes his freedom.

In order to collect detailed material about the anashists, Obadiy penetrates into their environment, becomes a messenger. The day before the trip to the Mayunkum steppes to collect the "evil thing", realizing the danger and responsibility of what is being undertaken, he unexpectedly receives great moral support: a concert of Old Bulgarian temple singing. Listening to the singers, “... this cry of life, the cry of a man with his hands lifted up high, talking about the eternal thirst to assert himself, ... to find a fulcrum in the vast expanses of the universe ...”, Obadiah receives the necessary energy, strength to fulfill his mission ... Under the influence of singing, the hero involuntarily recalls the story "The Six and the Seventh", which tells about the time of the civil war on the territory of Georgia, and finally understands the reason for the tragic ending when the Chekist Sandro, who infiltrated Guram Dzhokhadze's detachment, after singing together on the night before parting kills everyone and himself. A song pouring from the very

hearts, brings people together, inspires, fills souls with a sense of freedom and Sandro, splitting in two in the struggle of duty and conscience, having gotten the bandits, kills himself.

In this episode, music, symbolizing the feeling of freedom, fills the soul of the former seminarian. Ch. Aitmatov, through the lips of a hero, reflects: “Life, death, love, compassion

and inspiration - everything will be said in music, because in it, in music, we were able to achieve the highest freedom, for which we fought throughout history ... "

The day after the concert, Avdiy, together with the anashists, rushes to Mayunkum. As the hero meets the messengers, the original plan to simply collect material for the article gives way to a desire to save lost souls. Obadiah “... was possessed by a noble desire to turn their (anashists - V.D.) destinies to light by the power of words ...”, not knowing “... that evil opposes good even when good wants to help those who have entered the path of evil ... ”]

The culminating moment in the story with the Anashists is a dialogue between Avdi and the leader of the messengers Grishan, during which the views of the characters from the point of view of the problem of interest to me become obvious.

Grishan, realizing Kallistratov's plan to save young drug addicts, is trying to prove the illegality of Avdiy's actions, their senselessness. The ex-seminarian hears words that are similar to what the Coordinator Father once said to him: "And you, the savior-emissary, thought before about what force is opposed to you?" These words sound a direct threat, but the preacher remains true to himself. Obadiah believes that "... to withdraw, seeing the atrocity with his own eyes, ... is tantamount to a grave fall." Grishan claims that he, more than anyone else, gives everyone freedom in the form of a high from drugs, while the Callistratovs "... are deprived of even this self-deception."

However, in the very words of the leader of the Anashists lies the answer: freedom under the influence of a drug is self-deception, which means that neither the messengers nor Grishan have true freedom. That's why

the anashists attack Obadiya and, having severely beat him, throw him off the train. Notable fact: Grishan does not participate in the beating. He, like the biblical Pontius Pilate, washes his hands, giving the victim to be torn apart by the maddened crowd.

Thanks to a young body or some kind of miracle, Avdiy Kallistratov remains alive. Now it would seem that the hero will come to his senses, understand the danger of fighting the “windmills” of immorality, lack of spirituality, and lack of freedom. However, this does not happen. Avdiy, having barely recovered, falls into the “brigade” or “junta”, as the people themselves christened themselves, Ober-Kandalov, a former military man “... former from the penal battalion ...”], who went to Mayunkum for

shooting saigas to fulfill the meat delivery plan. The raid had a strong effect on Obadiah: “... he screamed and rushed about, as if in anticipation of the end of the world, - it seemed to him that everything was flying into tartaras, plunging into a fiery abyss ...” Wanting to end the cruel carnage, the hero wanted to turn people to God who came to the savannah hoping to earn bloody money. Avdiy “... wanted to stop the colossal extermination machine that was accelerating in the open spaces of the Mayunkum

savannah, - this all-crushing mechanized force ... I wanted to overcome the irresistible ... ”This force physically suppresses the hero. He is not trying to save, but it was almost impossible, because Ober-Kandalov opposed a cruel thought: “... whoever is not with us pulled up, so much so that his tongue was on one side at once. I would hang everyone, everyone who is against us, and in one string the whole globe, like a hoop, wrapped it around, and then no one would resist a single word of ours, and everyone would walk on

to the string ... "Obadiy" to the string "could not and did not want to, so he was crucified in saxaul. His “... the figure was somewhat reminiscent of a large bird with outstretched wings ...” The mention of the bird, the free image of which appears three times in the biblical legend of the novel, allows

to assert: the comparison testifies that Obadiy dies as a free person, while the Oberkandalites, deprived of all moral norms, in general of human likeness, are not free.

Father Coordinator, Anashists and Oberkandalites are a modern alternative to Avdiy, the Christ of the 20th century. They tried to force him to renounce his convictions, faith, freedom. However, just like two thousand years ago, Pontius Pilate hears a refusal three times from the lips of Christ, so modern Pilates cannot break the will of a free man - Avdiy Kallistratov.

The last character of the Mayunkum chapters, in the appendix to which the problem of freedom and non-freedom is investigated, is Boston Urkunchiev. The storyline of the character is intertwined with the line of wolves. The hero never meets Avdiy Kallistratov on the pages of the novel, but, nevertheless, his life is filled with the ideas of Christ of the twentieth century. Boston “... accumulates in itself healthy skills and principles of being and

his stay on earth, ... taking into account the experience of a man of the twentieth century, expresses aspirations for real humanism. "

The most important thing in the hero's life is his family (wife and little Kenjesh) and work, “... after all, from childhood he lived by work”. Boston puts all his soul into the hard work of the shepherd, almost around the clock dealing with lambs. He tries to introduce a rental contract in the brigade he leads, believing that for each "... business, someone in the end must ... be the owner." The desire for significant changes that give more freedom to make decisions and actions confirms and indicates the hero's desire not only for freedom on a narrow, concrete, but also on a global scale.

However, it is not possible to carry out the plan due to misunderstanding, indifference, indifference of the state farm management, which in certain circumstances turns into criminal permissiveness and misanthropy. This is what caused the enmity between Urkunchiev and the drunkard Bazarbay. It is indifference and misunderstanding in the general lack of spirituality that are the main reasons for the death of Ernazar, a friend and like-minded person of Boston, who perishes on the way to new pastures for livestock.

Boston is grieving over the death of Ernazar. Although, if you think about it, the character is not guilty of the tragedy that happened. Not Urkunchiev, but a society, indifferent and rigid, holding on,

like the official church, on dogmatism, it pushes the shepherds to a risky business. The author of "Plakhi" deduces the freedom of a character from the concept of "morality, that is, only a highly moral person who correlates his actions with conscience, according to Ch. Aitmatov, can be free. All these qualities are inherent in Boston Urkunchiev. After the death of Yernazar “... for a long time, years and years, Boston dreamed the same terrible dream forever imprinted in his memory ...”, in which the hero descends into an ominous abyss, where Yernazar found his last shelter frozen into the ice. A dream, in the course of which the shepherd experiences agony again and again, is

decisive in the question of morality, and hence in the question of the freedom of the character.

Human degradation and cruelty, intensified in the treatment of nature, the people around them, is the cause of the tragedy of Boston. The fact is that Bazarbai, having ruined the wolf's lair, leads the animals to the Boston dwelling. On repeated requests of the shepherd to give or sell the cubs

Bazarbai refused. Meanwhile, the wolves slaughtered the sheep, did not let their howls sleep peacefully at night. The hero, in order to protect his family and economy from such a disaster, ambushes and kills the wolf-father. His death is the first link in subsequent deaths. The next was his son Kenjesh and the she-wolf: Boston, wanting to shoot the beast that kidnapped the child, kills both. For the hero, the world fades, "... he disappeared, he was gone, in his place there was only a raging fiery darkness." From that moment on, the character, who differs from those around him by the presence of moral purity and freedom, loses it. This can be explained as follows: by killing the wolf-mother, who embodies and personifies Nature, its highest wisdom and intelligence, Boston kills itself in its offspring.

However, on the path of losing freedom, Boston goes even further, becoming the same unfree person as Kochkorbayev, Oberkandal and Anashists, bringing lynching to Bazarbay.

Concluding the conversation about the existence or absence of freedom among the heroes of the “Mayunkum” chapters of the novel, the following conclusions can be drawn. The only hero with exceptional freedom is Avdiy Kallistratov. The character who fought for the salvation of the "lost souls" of the Anashists and

Oberkandal, who preaches goodness, moral purity and freedom, perishes without changing his faith in a person, without renouncing the convictions of a free person. Anashists and Oberkandalites, deprived of moral principles, pursuing only one goal in life - enrichment, are deprived of freedom. At the same time, anashists, considering the intoxication of the drug as a release from

of all prohibitions, aggravate their lack of freedom.

Boston Urkunchiev, being an extraordinary, initially free person, as a result of the crime of human norms, following the lead of such as Kochkorbaev, Father Coordinator, anashists and Oberkandalists, loses freedom, puts an end to his life as a free person and the life of his kind.

27. Deepening the social analysis of reality in Ch. Aitmatov's story "Farewell, Gyulsary".

A writer from Kyrgyzstan now adequately represents both his people and all post-Soviet literature abroad. Achievements, interacting literatures, are judged by the achievements of writers such as Ch. Aitmatov.

After completing six classes, Aitmatov was the secretary of the village council, a tax agent, an accountant, and performed other work on the collective farm. After graduating from the Dzhambul Zootechnical School, he entered the Kyrgyz Agricultural Institute. It was at this time that short notes, essays, correspondences written by the future writer began to appear in the republican press. During his student years, Aitmatov also conducts philological research, as evidenced by the articles "Translations far from the original", "On the terminology of the Kyrgyz language." In this work, he is helped by his equally fluent knowledge of both his native and Russian languages. After working for three years in his specialty in an experimental animal husbandry, Aitmatov enters a two-year higher literary course in Moscow. Aitmatov made his first steps in writing in the fifties. In 1958, his first book "Face to Face" was published in Russian. Translation from Kyrgyz was carried out by A. Drozdov. This short story, but bright in content, tells about a dramatic period in our history - the Great Patriotic War. She rolled with tears of pain and loss to a distant Kyrgyz village. She burned Seide, the main character of the story, with a terrible and shameful word: "deserter."

After studying in Moscow, Aitmatov worked in the republican press, and then - for five years - as his own correspondent for the newspaper Pravda in Kyrgyzstan.

In the 60s, the writer wrote the stories "Camel Eye", "The First Teacher", "Poplar in a Red Headscarf", "Mother's Field". They talk about the difficult formation of Kyrgyzstan, about overcoming inertia and prejudice, about the victory of the human spirit.

In the 70s, Aitmatov continued to work in the genre of the story. The Early Cranes appear, telling about the difficult wartime, when teenagers, bypassing youth, stepped straight into adulthood. This is largely an autobiographical tale. Aitmatov is also from this generation. The White Steamer is a tragic story about a childhood destroyed by the cruelty of adults. This is one of the author's best stories, written in 1970.

Beginning with the story "Farewell, Gyulsary!"

twists and turns in the fates of heroes, sometimes tragic fates in the most sublime meaning of these words, when death itself serves to elevate a person.

The story "Farewell, Tulsary!" talks not only about some important social problems of the 40-50s, about mistakes and excesses in that period. Many mistakes of that time have been overcome, excesses have been corrected, but literature has deeper tasks, Rather than pointing out individual, even significant, mistakes and shortcomings of social life.

When analyzing the social connections of the hero of the story "Farewell, Gyulsary!" one should not forget about the historically specific, geographically precisely designated environment in which Tanabai Bakasov operates. The artistic persuasiveness of the story lies in the fact that the writer, through the power of talent, was able to show the fate of his contemporary, highlighting in it the essential social relationships of the world and man, he was able to give the story of the dramatic fate of one person a universal sound.

The development of the character of Tana6ai Bakasov goes in concentric circles of gradually expanding knowledge of life. Corporal Bakasov would not have learned much if he had stayed to work as a hammer in the Ail smithy. This was in the early post-war years, when all Soviet people lived in the "air of victory, like bread." Even then, in the head of the impatient Tanabai, the thought flashed about how to quickly and better improve the lives of fellow villagers. The whole story, in fact, became a summing up; it begins with those difficult last questions that usually once in a lifetime, at some critical moment, arise before a person: about the meaning of life, about a person's dignity, about the running time. The writer laid these two themes as the basis of artistic construction: the life of a person and the life of a pacer.

From the first pages of the story, these two characters are outlined - the collective farmer Tanabay Bakasov and the famous horse Gyulsary. And the whole action develops as the story of a restless man, beating against the sharp corners of life, a man who withstood the hardships of time. At the same time, the tragic story of the famous pacer Gyulsary unfolds, patiently enduring all the blows of fate, with an even step in life, from the winner of horse races to the wretched, driven old horse, who stretched out zeroes on the frozen steppe road on a cold February night.

A juxtaposition of these two fates is inevitable for a writer; juxtaposing them begins and ends the story; it runs like a nagging refrain through all the chapters — the old man and the old horse. The comparison is carried out according to the principle of similarity and according to the principle of dissimilarity. The analogy in this case would be dry, dead, flat. The artist needed such an ideological and compositional technique in order to emphasize the spiritual obsession of a person who has not resigned himself to his fate, who continues to fight for the cause to which he gave all his strength and the best years of his life. With each refrain, the author emphasizes the desire of the old shepherd to comprehend his past, to understand the past years.

And gradually Tanabai's stubborn desire to assert his innocence, his position as a communist, is growing. The old man indignantly recalls the absurd words of his daughter-in-law: "Look, why did you need to join the party, if you spent your whole life in shepherds and herdsmen, you were kicked out by old age ..."

Then, in a conversation with his daughter-in-law and son, Tanabai had not yet managed to find the right words about himself, about his fate. And on the way as a lady, he is not a magician to forget grievances. It took a sleepless night by a fire in the cold February darkness, next to a dying pacer, to mentally re-live his whole life, to remember the path of his beloved horse, in order to finally firmly say to himself: "I still need, I will be needed ..."

The finale is generally optimistic, but what an abyss of human suffering, strength of mind, insatiable striving for the ideal is revealed by the writer in the biography of the Kyrgyz herder and shepherd Tanabai Gakasov, who tore his sides and heart in blood in the struggle for his principles.

And in a story on a burning modern theme, a story about a Kyrgyz collective farmer, the chilling depth and inexhaustibility of the eternal questions of human life is revealed.

The path of Tanabai's cognition of his being, his time, is divided by the writer into two stages. The first covers the period when Tanabai worked as a herder, raised and nursed Gyulsary. It ends with a dramatic shock of the hero associated with the forcible expulsion of the pacer from his herd, the emasculation of Gyulsary. The second stage of Tanabai's social self-awareness is his work as a shepherd, a hard winter in the skinny sheep-shelters, a clash with the district prosecutor Selizbayev, and expulsion from the party.

In the first half of the story, Tanabai lives far from the artel, drives a herd of horses across the pastures, in which he immediately noticed an unusual pacer. This part of the story is painted in major, light colors, however, already here, working as a herdman, Tanabai saw the state of the artisan farm. The harsh winter and lack of food drove Tanabai to despair at times. Aitmatov notes: "The horses did not remember this, the man remembered about it." But spring came, bringing warmth, joy and food to the horses. In those first years, with the herd, Tana6ai enjoyed his strength, youth, he felt how the pacer was growing up, how "from a shaggy kurgan one and a half year old he was turning into a slender, strong stallion." Ate character and temperament delighted Tanabai. Only one passion so far possessed the pacer - the passion for running. He rushed among his peers like a yellow comet, "some incomprehensible force drove him tirelessly." And even when Tanabai traveled around the young horse, taught him to the saddle, Gyulsary “almost did not feel any embarrassment from him. It was easy and joyful for him to carry the rider on him. " This is an important detail in the life sense of the pacer and Tanabai: they both felt “easy and joyful”; they aroused the admiration of people who, seeing how swiftly and evenly the horse was running along the road, gasped: “Put

a bucket of water on it - and not a drop will splash out! " And the old herd keeper Torgoy said to Tanabai: “Thank you, well, I left. Now you will see how your pacer's star will rise! "

For Tanabai, those years were perhaps the best in the entire post-war period. "The gray horse of old age was still waiting for him beyond the pass, although close ..." He experienced happiness and courageous excitement when he flaunted in the saddle on his pacer. He recognized his true love for a woman and turned to her every time he passed her yard. At that time Tanabai and Gulysary experienced together the delightful feeling of victory in the Kyrgyz national races - alaman-baige. As the old horse herder Torgoy predicted, "the pacer's star has risen high." Everyone in the area already knew the famous Gyulsary. The fifth chapter of the story, describing the victory of the pacer on the big alaman-baiga, draws the highest point of the living unity of man and horse. This is one of the best pages of Aitmatov's prose, where the fullness of the feeling of life is permeated with the passionate drama of the struggle. After the races, Gyulsary and Tanabai went around to the shouts of enthusiastic shouts, and this is a well-deserved recognition. And everything that happens to the pacer and Tanabai after their joint celebration will be evaluated in the story from the point of view of a harmonious, true life.

And further dramatic events are already anticipated in the first half of the story. During these best years of his life, rejoicing at the growing pacer, Tanabai often asked himself and his friend, collective farm chairman Choro Sayakov, about matters in the artel economy, about the situation of collective farmers. Elected to members of the Audit Commission, Tanabai often pondered what was happening around him. As the pacer had a "passion for running," so Tana

Bai was often impatient. Choro's friend would often say to him, “You want to know, Tanabai, why are you unlucky? From impatience. By golly. Everything to you sooner and sooner. Give the world revolution immediately! What a revolution, an ordinary road, an ascent from Aleksandrovka, and then you can't bear it ... And what do you gain? Nothing. All the same, you sit there, upstairs, waiting for others. "

But Tanabai is impatient, hot, hot-tempered. He saw that the situation on the collective farm was bad, "the collective farm was all in debt, and the bank accounts were arrested." Tanabai often argued with his comrades in the kolkhoz office, asking, "how does this work out and when, finally, such a life will begin so that the state has something to give and so that people do not work for nothing." “No, it shouldn't be that way, comrades, something is wrong here, there’s some kind of snag here,” Tanabai said. “I don’t believe it should be that way. Either we have forgotten how to work or you are leading us incorrectly. "

And before the war, Tanabai was an active communist, and after passing the front, knowing the happiness of victory over fascism, he grew spiritually and morally. So all his fellow villagers felt. It is not for nothing that Chairman Choro, thinking about "how to do to raise the economy, feed the people and fulfill the plans," notices the main process in the spiritual development of his compatriots: "And the people are not the same, they want to live better ..."

Tanabai still cannot tell what the matter is; he only doubts whether the collective farm and district leaders are working correctly. He feels anxiety and personal responsibility for the fate of the common cause. He had his own "special" reasons for anxiety and anxiety. " They are very important both for understanding the protagonist of the story and for understanding the social meaning of the entire work. Artel affairs are in decline. Tanabai saw that the collective farmers “are now quietly laughing at him and, seeing him, they look defiantly in the face: well, how, they say, are things? Maybe you will undertake dispossession of kulaks again? Only from us now the demand is low. Where you sit, there you will get off. "

Such are the social origins of the old herd's personal drama, which grows into the drama of millions of honest peasants who believe in socialist cooperation in the countryside and are painfully experiencing zigzags and disruptions to collective agriculture.

And if you look from the point of view of the individual, it is easy to see that the failures and difficulties of restoring the post-war economy became personal and the problems of hundreds of thousands of peasants, such as Tanabai, ardently devoted to the ideals of socialism. The gap between the increased consciousness of people and difficult circumstances will look all the more sharp. This is how the exposition of Tanabai Bakasov's drama looks like. The most difficult acts of this drama are yet to come. So far, he evaluates a lot indirectly, based on the position of the pacer. So he meets the new chairman, proceeding from his attitude towards Gyulsary. And when a written order comes from the new chairman (it is quite typical that the signature under the order is illegible) to place the pacer in the collective farm stable, Tanabai senses impending disaster. Gyulsary is taken away from the herd, but he stubbornly runs away again into the herd, appearing in front of Tanabai with pieces of rope around his neck. And then one day the pacer hobbled around with wrought iron shackles - a log on his feet. Tanabai could not stand such treatment of his beloved horse, he freed him from the shackles and, handing over Gyulsary to the grooms, threatened the new chairman to "smash his head with a swarm."

In the ninth chapter, an event takes place that puts an end to the former free life of Gyulsary: the pacer is emasculated. Emasculating such a breeding stallion as Gyulsary meant much impoverishment and weakening the genetic branch of collective farm horse breeding, but the chairman of the collective farm, Aldanov, was not thinking about economic interests, but about his external prestige: he wanted to show off riding a famous pacer. And earlier, before this terrible operation, the relationship between the horse and the chairman was bad: Gyulsary could not stand the fusel smell that often emanated from the new chairman. They said that “he is a tough person, he went to 6 big bosses. At the very first meeting, he warned that he would severely punish the negligent, and for failure to comply with the minimum he threatened to court ... ”But the chairman appears for the first time in the scene of the castration of a horse. Aldanov "stands importantly, spreading his thick short legs in wide riding breeches ... He put one hand on his hips, with the other twists a button on his tunic." This scene is one of the most striking in its skill, in its precise psychological drawing. Strong, healthy people perform a cruel, unjustified by any economic considerations, operation of emasculation of a noble, talented horse. The operation is performed on a bright sunny day, to the sounds of a childish song during the game, and especially contrasts with the gloomy plans of people who decided to pacify the rebellious horse. When he was thrown to the ground, tied tightly with lassos and crushed by his knees, then Chairman Aldanov jumped up, no longer fearing the pacer, “squatted down at the head of the bed, doused him with yesterday's fusel scent and smiled In outright hatred and triumph, as if you were not lying in front of him a horse, but a man, his enemy is fierce. " The man was still squatting in front of him, looking and waiting for something: "And suddenly a sharp pain blew up the light in the eyes" of the pacer, "a bright red flame flared up, and immediately it became dark, black-black ..."

Of course, this is the murder of Gyulsary. It is no coincidence that the sycophantic Ibrahim, who participated in the emasculation of the horse, said, rubbing his hands: “Now he will not run anywhere. All - run over. " And for such a horse, not to run is not to live. An unreasonable operation carried out from Gyulsary prompted Tanabai to make new sad discourses about the chairman Aldanov and collective farm affairs. He told his wife: “No, it still seems to me that our new chairman is a bad person. The heart feels. " Reflection begins with a direct, close to Tanabai reason-relationship to the pacer. After dinner, circling around the herd on the steppe, Tanabai tries to distract himself from gloomy thoughts: “Maybe you really can't judge a person like that? Silly, of course. Because, probably, because I am getting old, because I drive the herd all year round, I do not see and do not know anything. " However, Tanabai cannot get away from doubts, from anxious reflections. He recalled, “how they once started the collective farm, how they promised the people a happy life ... Well, at first they healed well. They would have healed even better if it hadn’t been for this damned war. ” And is it only about the war? After all, many years have passed since the war, and we “are all repairing the economy like an old yurt. If you cover it in a place, a hole will open in another. From what?"

The herdman is approaching the most serious moment of his reflections, he is still shy in front of vague guesses, he is trying to speak frankly with his friend Choro: “If I'm confusing, let him say, but if not? What then? "

A stubborn, persistent thought torments Tanabai's heart and mind; he is sure of only one thing: "It should not be like this," but as it should be, he does not dare to immediately provide, he still refers to the district and regional leaders: "There are wise people ...". Tanabai recalls how, in the 1930s, representatives from the region came, immediately went to the collective farmers, explained, advised. “And now he will come and shout at the chairman in the office, but he does not speak to the village council at all. At the party meeting, he will speak more and more about the international situation, and the situation on the collective farm does not seem to be such an important matter. work, give us a plan, and that's it ... "

Tanabai seems to feel the views of people who “just ask:“ Well, here you are, a party man, you started a collective farm - you pulled your throat most of all, explain to us how it all turns out? What do you tell them? " What could he say, what could the restless herd man say to them, if not everything was clear to him, to his party conscience? For example, “why does the collective farm seem to be not your own, as then, but like a stranger? Then the meeting decided what was the law. They knew that they had adopted the law themselves and that they had to fulfill it. And now the meeting is nothing but empty talk. No one is whole before you. It seems that the collective farm is not managed by the collective farmers themselves, but someone from the outside. They twist, twirl the farm this way and that, but there is no sense. "

This is where the realm of moral issues begins.

Before leaving for a new nomadic camp, he kept racking his brains over difficult questions, trying to understand "what is the catch here." At the end of the eleventh chapter, Tanabai drives his herd across a large meadow, past the ail, and when he saw his beloved Bubyuzhan's house, where he usually drove on his pacer, the herd's heart ached: “Now there was no woman or pacer Gyulsary for him. Gone, everything is in the past, that couple rustled like a flock of gray geese in the spring ... "

Here, for the second time, a beautiful Kyrgyz song about a white Camel who has lost her black-eyed camel appears in the narrative. The first time this sad song was sung to Tanabai by his wife Dasaidar, when the pacer was taken away from them and put into the stable. Listening then to the ancient music of nomads, Tanabai thought about his youth, again saw in his aging wife "a swarthy girl with braids falling on her shoulders", recalled himself, "young-young", and his former intimacy with that girl whom he fell in love with for her songs , for her playing the temir-komuz ... Later, in the last chapters, the saddest, tragic notes of the life of the pacer and his master will be interwoven into this rhythm of a sad, pensive melody. And here is the magic of folk art: everything dark and difficult that happened to Tanabai and Gyulsary finds in an ancient Kyrgyz song a kind of emotional outlet, catharsis, revealing to the reader the eternal depth of human suffering, helping to correctly perceive the dramatic scenes of the story. And the system "man and social environment", which the writer explores, is logically supplemented by more general categories - "man and environment", "man and the world". At the same time, the social guidelines of artistic research are by no means dissolved, not canceled; they line up in a more complex perspective - temporal and spiritual.

This is how the first stage of social insight of Tanabay Bakasov looks like. Then Tanabai had to look at the world more directly and directly. And, passing over to the second half of the life story of “the old man and the old horse,” the reader feels that the topic of social maturation of a person, who will face considerable life trials, is coming to the fore.

The next stage in the spiritual evolution of the hero of the story begins strictly, busily: "In the autumn of that year, the fate of Tanabai Bakasov suddenly turned around." The herder became a shepherd. Of course, "it will be boring with sheep." But - a party assignment, a duty of a communist, for Tanabai these words contain his whole life. Yes, and Party organizer Choro honestly says to his old friend: "I can't help you, Tanabai."

Before sending his hero to the most difficult test, the writer draws some encouraging features of collective farm life: the artel received a new car, serious plans are being developed to raise animal husbandry, in particular, sheep breeding. Tanabaya is glad that things on the collective farm will improve a little, that he is going to a meeting of livestock breeders in the district center, where he must speak and make a high commitment. True, he had not yet seen the sheep and the shepherd, his assistants and sponsored young shepherds, too. But he feels that some kind of change is impending. The work of a shepherd on a Kyrgyz collective farm is one of the most difficult. Therefore, going to his flocks, Tanabai did not expect easy success.

Before sending his hero to the mountains, to the flocks of sheep, the writer again showed his close friend, party organizer Choro, and the pacer Gyulsary. Bitter premonitions arise when you meet them again. An old friend, Party organizer Choro persuaded Tanabai to speak at a meeting of livestock breeders, to take on unreasonable obligations and did not advise him to say "nothing else", something that was boiling in his soul. Recalling his performance with shame, Tanabai wondered that Choro had become so cautious. Tanabai felt: something in Choro "shifted, changed somehow ... learned to trick, it seems ..." And Gyulsary? Tanabai did not see him running. The narrator shows the pacer on the way of Choro from the regional center to his native village, and the first phrases about the pacer are alarming, then astonishing: the horse was typing its hooves along the evening road, like a running car. Of all the past, he has only one passion for running. Everything else has long since died in him. They killed him so that he knew only the saddle and the road. " From now on, Gyulsary will no longer be worried, willful, strive to fulfill his impulses and desires. Now he will not have any impulses, desires. A living, extraordinary horse is killed in him.

The shepherd's head was filled with obsessive questions: “What is all this for? .. Why are we raising sheep if we cannot save them? Who is to blame for this? Who?" The first spring in the uterine ota cost dearly to the shepherd.

re. Tanabai turned gray and aged for many years. And on sleepless nights, when Tanabai was suffocating from his hurtful and bitter thoughts, “a dark, terrible anger arose in his soul. She rose, covering her eyes with a black gloom of hatred for everything that was happening here, for this disastrous sheepfold, for the sheep, for herself, for her life, for everything for which he fought here, like a fish on ice. "

The last state - dullness, indifference - may be the most terrible for Tanabai. It is no coincidence that the writer presents the 6th diagram of his hero in this very chapter, which shows the extreme degrees of Tanabai's denial of the order established on the collective farm. Tanabai's biography, his character are also given in comparison with the character of his older brother Kulubai. Once in their youth, both of them worked for the same owner, and he cheated them, paid nothing. Tanabai then openly threatened the owner: "I will remember that when I grow up." But Kulubai said nothing, he was smarter and more experienced. He wanted to "become the owner himself, acquire cattle, get hold of land." Then he said to Tanabai: "I will be the master - I will never offend the worker." And when collectivization began, Tanabai embraced the ideas of artel management with all his heart. At the meeting of the village council, the lists of fellow villagers subject to dispossession were discussed. And, having reached the name of Tanabaev's brother - Kulubai, the village councilors argued. Choro doubted whether it was necessary to dispossess Kulubai? After all, he himself is from the poor. He did not engage in hostile agitation. The young, decisive Tanabai chopped in those years from the shoulder. “You always doubt,” he snapped at Choro, “you’re afraid that what’s wrong. Once it is on the list, it means a fist! And no mercy! For the sake of Soviet power, I will not regret my own father. "

This act of Tanabai was condemned by many fellow villagers. The narrator also disapproves of him. Kulubai's industriousness and diligence, his readiness to give the collective farm all his household were known to the residents of ailchans. Then people recoiled from Tanabai, and when voting his candidacy they began to abstain: "So little by little, he dropped out of the asset." It is not for nothing that after Tanabai's recollections of his skirmish with his brother Kulubai, the writer again brings his hero back to bitter thoughts about what happened to the collective farm and why the artel economy was brought to decline. “Or maybe they made a mistake, went the wrong way, the wrong way? - thought Tanabai, but immediately stopped himself: - No, it shouldn't be so, it shouldn't! The road was right. What then? Lost? Lost? When and how did this happen? " Tanabai did not fulfill his reviews. Large losses were in the flock. In connection with the case of Tanabai Bakasov, the shepherd of the "White stones" collective farm, the bureau of the regional party committee is meeting. Chingiz Aitmatov writes psychologically detailed portraits of people who are supposed to investigate the Tanabai case. Among them is the secretary of the district committee of the Komsomol Kerimbekov, an impetuous, direct, honest man who ardently spoke out in defense of the shepherd and demanded to punish Segizbayev for insulting Tanabai. One or two strokes show the chairman of the collective farm Aldanov, who avenged Tanabai for the old threat to "smash his head with a swarm" for the pacer. With a pain in his heart, the narrator describes the behavior of the party organizer Choro Sayakov at the bureau: he confirmed the factual accuracy of the prosecutor's memorandum and wanted to explain something else, to defend Tanabai, but the secretary interrupted Choro's speech, and he fell silent. Tanabai was expelled from the ranks of the party. When he listened to the accusations against him, and was horrified. Having gone through the whole war, they "did not suspect that the heart could scream with such a cry as it was screaming now." Segizbaev's report turned out to be much more terrible than himself. You cannot throw yourself against her with a pitchfork in your hands. "

In the scenes of the meeting of the bureau of the district committee, the subsequent trip of Tanabai to the district committee and the regional committee, the writer shows that history is created by living people with their own characters, passions, virtues and weaknesses. A thousand random circumstances influenced the decision of the question about Tanabai, about his fate.

At the end of the story, when Tanabai buried Choro Sayakov, when there was no longer any hope of revising the unjust decision of the district committee to expel from the party, the ancient Kyrgyz lament sounds for the great hunter Karagul, who thoughtlessly destroyed everything that “came to live and multiply”: “He interrupted he is in the mountains around all the game. The queens did not spare the pregnant women, did not spare the small cubs. He exterminated the herd of the Gray Goat, the first mother of the goat race. And he even raised his hand to the old Gray Goat and the first mother to the Gray Goat. And he was cursed by her: the goat took him into the inaccessible rocks, from where there was no exit, and with a cry said to the great hunter Karagul: “You will not leave your home forever, and no one can save you. Let your father cry over you, as I cry for my murdered children, for my lost family. " The meaning of crying for the great hunter Karagul is multifaceted. When Tanabai was expelled from the party, he “became unsure of himself, felt guilty in front of everyone. Somehow I fell asleep. " And here's what is remarkable: how the people reacted to Tanabai in those days. In one phrase - "no one stabbed his eyes" - the writer made him feel the immeasurable generosity of the people towards their sons, who can be wrong, but also recognize their mistakes.

28. Affirmation of moral ideals in the story of Ch. Aitmatov "Mother's Field".

Chingiz Aitmatov tries to penetrate the innermost secrets of life, he does not bypass the most pressing issues generated by the twentieth century.

"Mother's Field" became a work close to realism, it marked the transition

writer to the most severe realism, which reached its maturity in the stories "Farewell, Gyulsary!" (1966), “White Steamer” (1970), “Early Cranes” (1975), in the novel “Storm Stop” (1980).

The movement of history, requiring from the individual person spiritual perseverance and unparalleled endurance, as in The First Teacher, continued to occupy the writer in The Mother's Field, one of the most tragic works of Chingiz Aitmatov.

The story begins and ends with the words about the grandson Zhanbolot. And this is not just a compositional technique for framing Tolgonai's monologue. If we recall that Aliman, the mother of Zhanbolot, also goes through the whole story and is, along with Tolgonai, the heroine of the Mother's Field, then the writer's intention becomes clearer. The fate of women-mothers - Tolgogai, Alman - is what interests the writer.

The situation is extreme, very dramatic: in the face of death, a person usually remembers that one cannot take with him to the grave. This intense drama immediately attracts our attention to the old Tolgonai. Moreover, the field with which she speaks also claims that “a person must find out the truth,” even if he is only twelve years old. Tolgonai only fears how the boy will be able to perceive the harsh truth, “what will he think, how will he look at the past, will he reach the truth with his mind and heart,” if he will not turn his back to life after this truth.

We do not yet know what kind of boy we are talking about, by whom he is brought to old Tolgonai, we only know that she is lonely and that this one boy lives with her, trusting and ingenuous, and for him old Tolgonai must "open his eyes to himself."

The writer has been exploring the fate of one Kyrgyz woman, Tolgonai Suvankulova, for half a century - from the twenties to the present day. The story is structured as a monologue of an old akenshina, who, alone with Mother Earth, recalls a long, difficult life.

Tolgonai begins from his childhood, when she guarded the crops with a barefoot, shaggy girl,

Pictures of happy youth appear transformed in the memories of old Tolgonai.

Aitmatov keeps the description of happy moments on the verge of romantic and realistic perception. Here is a description of Suvankul's caress: "With a hard, hard, like cast iron hand, Suvankul quietly stroked my face, forehead, hair, and even through his palm I could hear his heart pounding violently and joyfully."

The writer does not describe the details of Tolgonai's pre-war life, we do not see how her three sons grow up. Aitmatov only paints a scene of the arrival of the first tractor on a collective farm field, selfless collective labor on the ground, the appearance in the Suvankulov family of a beautiful girl Aliman, who became the wife of her eldest son, Kasym. It is important for the author to convey the happy atmosphere of the pre-war socialist village, in which the dreams of rural workers have come true. On the eve of the war, in the evening, Tolgonai returned with her husband from work, thought about the growing sons, about the flying years and, looking at the sky, saw the Strawmaker's Road, the Milky Way, “something trembled in my chest”; she remembered: “and that first night, and our love, and youth, and that mighty grain grower, about which I dreamed. So, everything came true, - the woman thinks happily, - everything we dreamed of! Yes, the land and water became ours, we plowed, sowed, threshed our grain - that means that what we thought about on the first night came true. "

The war brings down blow after blow on a simple Kyrgyz woman: her three sons and her husband go to the front. The author depicts only individual episodes of the heroine's difficult military life, but these are the very moments when suffering with renewed vigor fell on Tolgonai and her soul absorbed new pain and anguish. Among such episodes is the fleeting meeting of Tolgonai and Aliman with Maselbek, who, as part of a military train, rushed past the station, having only managed to shout two words to them on the code and toss his hat to his mother. A frantically rushing train and for one short moment the face of young Maselbek: "The wind ruffled his hair, the flaps of his greatcoat beat like wings, and on his face and in his eyes there was joy, and sorrow, and regret, and forgiveness!" This is one of the most exciting scenes in the story: a mother running after an iron train, a mother hugging a cold steel rail in tears and groans; "The clatter of the wheels went further and further and further, then it died down." After this meeting, Tolgonai returned to her native village "yellow, with sunken, exhausted eyes, as after a long illness." The writer notes outward changes in the face of the old woman very sparingly, in one or two phrases - in Tolgonai's conversation with mother earth or with his daughter-in-law. It is sadly noted how the gray hair hit Tolgonai's head, how she left, gritting her teeth. But she did not even imagine what trials awaited her in the future: the death of her three sons and her husband, the famine of Ail children and women, a desperate attempt to collect the last kilograms of seeds from starving families and, in spite of all the prescriptions of the collective farm charter and wartime requirements, to sow over the plan a small a section of the deposit to alleviate the suffering of the ail residents.

Pictures of a military, half-starved village in "Mother's Field" are among the best pages of Soviet multinational prose dedicated to the selfless labor of women, old people and adolescents in difficult times. Tolgonai went to the courtyards to ask for a handful of seeds to sow an extra piece of land for her fellow countrymen. I collected 2 bags. And they were stolen by a deserter with his friends ... How to look people in the eye? It is difficult to imagine more difficult trials that the writer offers his heroes in "Mother's Field".

The popular view of the tragic events taking place is expressed primarily in the symbolic dialogue of Tolgonai with mother earth, with the mother's field, a dialogue that, in essence, leads the story, emotionally preparing the reader for the upcoming presentation of memories, sometimes anticipating events. The story begins and ends with a dialogue with mother earth. The earth knows how to be silent with understanding, watching with pain how Tolgonai changes and grows old. After she only for a moment saw the middle son of Masel-bek in the roaring military train flying past the station, past Tolgonai and Aliman, the earth remarks: “Then you became silent, harsh. Silently came here and left, gritting her teeth. But it was clear to me, I saw it in my eyes, each time it became more and more difficult for you. " The maternal field suffers from human wars, it wants people to work peacefully, turning our planet into a wonderful home for humans. Together with people, the maternal field in Ch. Aitmatov's story rejoiced on Victory Day, but the earth very accurately determines the complex emotional tone of the experiences of those days: “I always remember the day when you people met soldiers from the front, but I still cannot tell Tolgonai, which was more - joy or sorrow. " It was a truly heartbreaking sight

Shche: a crowd of Kyrgyz women, children, old people and invalids stood on the outskirts of the village and with bated breath and waited for the soldiers to return after the victory. “Each one silently thought about his own, bowing his head. People were waiting for the decision of fate. Everyone asked himself: who will return, who will not? Who will wait and who will not? Life and further destiny depended on this. " And on the road appeared only one soldier with an overcoat and a duffel bag thrown over his shoulder. “He was approaching, but none of us moved. The faces of the people were bewildered. We were still waiting for some kind of miracle. We could not believe our eyes, because we expected not one, but many. "

In the most difficult years, “the people did not disperse, they remained the people,” Tolgonai recalled. “The women of that time are now old women, children have long been fathers and mothers of families, it is true that they have already forgotten about those days, and every time I see them, I remember what they were then. They stand before their eyes as they were - naked and hungry. How they worked then, how they waited for victory, how they cried and how they took courage. According to the Kyrgyz custom, it is not customary to immediately bring sad news to a person; aksakals decide at what moment it will be more tactful to report a disaster, and gradually prepare a person for it. In this concern of the people, the old ancestral instinct of self-preservation is reflected, which has taken the form of nationwide sympathy, compassion, which to some extent relieves the mental pain and misfortune of the victim. Chingiz Aitmatov twice describes scenes of general grief - when the death of Suvankul and Kasym was reported and when Maselbek's last letter was received. In the first case, an aksakal comes to Tolgonai's field and takes her ail, helping her with a word, helping her dismount at her native Court, where a crowd of fellow villagers has already gathered. Tolgonai is seized with a terrible premonition, "already dead", slowly walking towards the house. Silently, women quickly approached her, took her hands and told her about the terrible news.

The people not only sympathize, they actively intervene in events, while maintaining dignity and common sense. After the war, when the deserter Jenshenkul was tried for fleeing from the front, for the stolen widow's wheat. The next morning the deserter's wife was no longer in the village. It turns out that at night fellow villagers came to Jenshenkul's wife, loaded all her goods onto carts and said: “Go wherever you want. You have no place in our village. " In these harsh simple words, there is a popular condemnation of the deserter and his wife, a deep understanding of the grief of Tolgonai and Aliman.