Volodya Maximov. Maksimov Vladimir Emelyanovich (Samsonov Lev Alekseevich) (1930-1995)

Read also

Encyclopedic information

Graduated from the hunting department of the Irkutsk Agricultural Institute, the Literary Institute named after V.I. A.M. Gorky. He is better known as a prose writer, author of novellas and short stories with an autobiographical basis. Travels and expeditions, the life of Siberian nature, youthful love - these are the main themes of the works.

Irkutsk. Historical and Local Lore Dictionary. Irkutsk, 2011

Biography

Maximov recalls:

« At my fourteen years old, my grandmother Ksenia Fyodorovna, from the famous Cossack family of the Lyubimovs, exiled to Siberia for participating in the Pugachev uprising, presented me with Yesenin's three-volume book. I still have it».

The teenager was struck by the amazing musicality of Yesenin's lines, and he undertook to write poetry, " ". The family soon moved to where the future writer graduated from high school.

After graduating from school, he worked as a car inspector at the Angarsk CHP - 10. Then he entered the hunting department of the Irkutsk Agricultural Institute, which he graduated in 1972. The Faculty of Hunting Science was transferred to Irkutsk from the Fur and Fur Academy in Moscow. He was the only one in the USSR who trained hunting specialists, who, as a rule, had an industrial practice twice a year, which took place at the request of the student, virtually anywhere in the country.

Studying at the institute opened the world to Vladimir Maksimov: during practice, he visited the Khabarovsk Territory (Sikhote - Alin Nature Reserve), Chukotka, the Commanders, Sakhalin, Kamchatka, went to the Pacific Ocean on a cat-registering ship with a call to Canada, Japan, traveled all over Irkutsk region.

After the institute, Vladimir Pavlovich completed his postgraduate studies at the Zoological Institute in Leningrad, worked at the White Sea Biological Station, at the Limnological Institute at.

Feeling a craving for creativity, he entered the literary institute. A. M. Gorky, studied at the seminar of the poet Vladimir Tsybin. In 1987 he graduated from the literary institute, worked in the newspapers "Soviet Youth", "Russian East", "Narodnaya Gazeta", the magazine "Okhota i priroda", etc.

During the years of perestroika, he changed several places of work: from a loader of a food base to a teacher at a school, a drilling foreman, a swimming instructor. There was little time for creativity, but it was during these years that Vladimir Pavlovich, along with poetry, began to write stories. His first story was published in 1979 in the Angarsk newspaper "The Banner of Communism" and was called "The First Rain".

In 1993, the editorial office of the "Vestnik" newspaper of the Angarsk Electrolysis Chemical Combine published a small collection of poems "An Unexpected Encounter", and in 1994 the publishing house of JSC "Format" (Angarsk) published a collection of stories "Three Days Until Autumn".

In 1993, Vladimir Pavlovich took part in the Beijing - Paris bike ride. Since his youth, he has been fond of sports: he swims, plays football, goes in for cycling.

The poems written during a trip to Europe were included in the collection "Parisian Notebook", it was published as a supplement to the Irkutsk newspaper "Gubernia" in 1996.

In 1998 Maksimov became a member of the Writers' Union of Russia. And in 1997 in the fifth issue of the magazine "Youth" was published the short story "The Unwritten Story" with a short introduction by V. Rasputin. In the same year, V. Maksimov's three books "Zagon", "Behind the Curtain, from This Side", "Frosty Kiss" were published. These small in volume, including several stories, books were prepared by the publishing house of the magazine "Siberia" and printed on paper of far from being the best quality (it was such a time!).

Stories from these collections Vladimir Pavlovich included in his "first, real", as he considered the book - "The Formula of Beauty." There were new, previously unpublished novellas "The Formula of Beauty" and "The Landing of the Soul". In these stories, the author recalls his youthful hobbies, talks about love and affection for his native nature, reflects on what beauty is.

At the very end of 1999, or rather, on December 30, Vladimir Maksimov published a new collection of poems "My Sister Autumn ...", which incorporated poems written in the period from 1965 to 1998. The poem "Angarsk" from this collection became a song about the city, the music for which was composed by Evgeny Yakushenko.

In 2004, the book "That Summer ..." was published, composed of two prose cycles: "Baikal Tales" and "Days of Our Life".

In 2005, the publishing house "Irkutsk Writer" published the book "Don't Look Back", the genre of which V. Maksimov defined as a novel - a parallel. Why parallel? There are two main characters in the novel: Igor Vetrov, who lives and acts in real time, and Oleg Sanin, unknown to Igor, whose diary Vetrov found in the attic of the hunter's house, where he lived for some time while in practice. At first glance, the heroes, their actions are similar, but only at first glance.

« ", - says V. Maksimov.

But the poems of this collection about childhood, youth, first love turned out to be interesting and not only to relatives and friends, Vladimir Pavlovich was repeatedly convinced of this at meetings with readers in libraries and the region.

In 2008, the well-known not only in, but also in Russia publisher G. Sapronov prepared the book V Maksimov "Premonition of miracles". It consists of a story and ten stories that were written, unlike others, in the 21st century.

Vladimir Pavlovich is a laureate of several regional journalistic prizes, in 2001 he was awarded a diploma of the Ministry of Railways and the Secretariat of the Union of Writers of Russia "For literary coverage of the problems of the Transsib". He is a frequent visitor to the libraries of our city and region.

Essays

Books

- An Unexpected Meeting: Poems. - Angarsk: Gaz editorial office. "Bulletin", 1993.

- Three days until autumn. - Angarsk: Publishing house of JSC "Format", 1994.

- Corral: Stories. - Irkutsk: Zhurn. Siberia, 1997.

- Behind the curtain, on this side: Stories. - Irkutsk: Zhurn. Siberia, 1997.

- Frosty Kiss: Stories. - Irkutsk: Publishing house of LLP zhurn. Siberia, 1997.

- Formula of beauty: Stories and stories. - Irkutsk: Vost. - Sib. book publishing house, 1998.

- My sister Autumn ...: Poems. - Irkutsk: Vost. - Sib. book publishing house, 1999.

- That summer ... Narratives of the last century: Stories, stories. - Irkutsk: Irkutsk writer, 2004.

- Don't Look Back: Roman. - Irkutsk: Irkutsk writer, 2005.

- Premonition of miracles: Story, stories. - Irkutsk: Publisher Sapronov, 2008.

Publications in periodicals

- Notes of a biased person // Siberia. - 1991. - No. 4. - P. 97–105. Publicistic article on the environmental topic.

- Three meetings: Story // Siberia. - 1999. - No. 3. - P. 159-161.

- But there was a case: Story // Siberia. - 2002. - No. 4. - P. 82 - 98.

- We will never be young again: Story // Siberia. - 2003. No. 6. - C 91-141.

- "Don't look back ...": [excerpt from their novel] // Siberia. - 2005. - No. 6. - P. 91–148.

Interview, conversations with the writer

- "Yes, I am a happy person": [journalist O. Bykov spoke with the writer] // Vost. - Sib. truth. - 2008 .-- June 26. - S. 4.

- Under the sound of car wheels: [O. Gulevsky conducted the conversation] // Obl. gas. - 2007 .-- Apr 2. - S. 4.

- In memory of a sunny bunny: [N. Kuklina talked to the writer] // Coachman. - 2007 .-- 6 July. - S. 15.

- "Consonance of the soul and the world": [interview with the writer was conducted by G. Kotikova] // Business world of Siberia = Busieness Word Siberia. - 2007. -№ 1-2. - S. 108 - 109.

- "It is impossible to achieve the ideal, but it is necessary to strive for it": [conversation with the writer was conducted by O. Lunyak] // Irkutsk speaks and shows. - 1999 .-- Jan 29.

Literature

- Lensky J. Debut in his youth // Vost. - Sib. truth. - 1997 .-- Aug. 27.

- Nikolaeva N."My sister is autumn ..." appeared in winter // Coachman. - 200. - No. 4 (January 28). - S. 3.

- Yasnikova T. Autumn has a brother ... // CM Number one. - 2000 .-- June 9.

- Klochkovsky A. A book that energizes // culture: Vesti. Problems. Destiny. - 2004 .-- Nov. - S. 15.

- About the book "That Summer ..."

- Kornilov V. Taigou marked destinies (Reflections on the novel by Vladimir Maksimov "Don't look back") // Your newspaper. - 2006 .-- June 29. - S. 2.

- Lazarev A. Literary events of Irkutsk // All about communication. - 2007 .-- April 3. - S. 8.

- About the collection "In memory of a sunny bunny".

Vladimir Pavlovich Maksimov: the harmony of the soul and the world

“Our constant mistake is that we do not take seriously the given, passing hour of life, that we live in the past or the future, that we are all waiting for some special hour when our life will unfold in all its significance, and we do not know that it is flows like water between fingers, like a precious grain from a bag of holes, not realizing that the most precious day is ... Confucius was right: “The past is gone. There is no future yet. There is only the present. "

This is how the parallel novel "Don't Look Back" by the Irkutsk writer begins. There is only the present ... In the present, on June 29, 2008, Vladimir Pavlovich turned 60 years old.

"In memory of the sunny bunny

It will return to early childhood.

Mama there, little boy

Goes to visit her grandmother.

Painted house, stove ...

Peacefully the lamp burns.

Grandma Ksenia: "Daughter ?!" -

He says to my mom.

And so cozy, calm

Sit quietly in the furnace.

Drink milk, eat a crust

And look at the icons. "

This is how Vladimir Pavlovich saw his childhood in his mature years. He recalls: “When I was fourteen, my grandmother Ksenia Fyodorovna, from the famous Cossack family of the Lyubimovs, who had been exiled to Siberia for participating in the Pugachev uprising, gave me a three-volume Yesenin book. I still have it ”. The teenager was struck by the amazing musicality of Yesenin's lines, and he undertook to write poetry, " wrote a huge number of them, probably no less than four hundred. True, I soon had the sense to understand that this was not poetry. And I burned everything mercilessly". Soon the family moved to Angarsk, where the future writer graduated from high school.

After leaving school, he worked as a car inspector at the Angarsk CHP-10. Then he entered the hunting department of the Irkutsk Agricultural Institute, from which he graduated in 1972. The Faculty of Hunting Science was transferred to Irkutsk from the Fur and Fur Academy in Moscow. He was the only one in the USSR who trained hunting specialists, who, as a rule, had an industrial practice twice a year, which took place at the request of the student, virtually anywhere in the country.

Studying at the institute opened the world to Vladimir Maksimov: during practice, he visited the Khabarovsk Territory (Sikhote - Alinsky Nature Reserve, Chukotka, Commanders, Sakhalin, Kamchatka, went to the Pacific Ocean on a ship to register seals with a call to Canada, Japan, traveled all over Irkutsk region). He was amazed by the beauty of nature, overwhelmed by the impressions of what he saw, which were reflected in future books. After the institute, Vladimir Pavlovich completed his postgraduate studies at the Zoological Institute in Leningrad, worked at the White Sea Biological Station, at the Limnological Institute on Lake Baikal. Feeling a craving for creativity, he entered the literary institute. A. M. Gorky, studied at the seminar of the poet Vladimir Tsybin. In 1987 he graduated from the literary institute, collaborated in the newspapers "Soviet Youth", "Russian East", "Narodnaya Gazeta", the magazine "Okhota i priroda", etc.

During the years of perestroika, he changed several places of work: from a loader of a food base to a teacher at a school, a drilling foreman, a swimming instructor. There was little time for creativity, but it was during these years that Vladimir Pavlovich, along with poetry, began to write stories. His first story was published in 1979 in the Angarsk newspaper "The Banner of Communism" and was called "The First Rain". In 1993, the editorial office of the "Vestnik" newspaper of the Angarsk Electrolysis Chemical Combine published a small collection of poems "An Unexpected Encounter", and in 1994 the publishing house of JSC "Format" (Angarsk) published a collection of stories "Three Days Until Autumn".

Since his youth, Vladimir Pavlovich has been fond of sports: he swims, plays football, goes in for cycling.

In 1993, he took part in the Beijing-Paris bike ride.

He recalled these days:

“As soon as my bike crossed the Polish border, I felt an extraordinary surge of creativity. In the three months after that, I wrote 28 poems. And in Paris he met the famous writer - emigrant Vladimir Maksimov ... "

Maksimov Sr. spoke well of the stories of Maksimov Jr.

“Farewell Paris, No regrets,

But with sadness I part with you.

Nothing awaits, I know, at home.

But I still want to go home. "

“I want to go home,” because in prosperous Europe, nostalgia grips me and pulls me home, to Siberia, to Lake Baikal.

Nostalgia

This feeling of nostalgia

This is mortal anguish.

These chains. These weights.

It blew at the temple

This feeling of nostalgia

Overtaking here,

In the center of pretty Europe

As if all the air has been drunk.

It's a strange confusion

Nailed suddenly

So ridiculous, incomprehensible

It looks like a fright.

So much like an eclipse

At the heart of the day.

But at such moments

We understand ourselves.

This feeling of nostalgia ...

Don't understand. Can't explain.

And it is not accepted about it

Here in Europe, talk.

Bavaria, September 1993

The poems written during a trip to Europe were included in the collection "Parisian Notebook", it was published as a supplement to the Irkutsk newspaper "Gubernia" in 1996. In 1998 Maksimov became a member of the Writers' Union of Russia. And in 1997 in the fifth issue of the magazine "Youth" was published the short story "An Unwritten Story" with a short preface. In the same year, V. Maksimov's three books "Zagon", "Behind the Curtain, from This Side", "Frosty Kiss" were published. These small in volume, including several stories, books were prepared by the publishing house of the magazine "Siberia" and printed on paper of far from being the best quality (it was such a time!).

Stories from these collections Vladimir Pavlovich included in his "first, real", as he considered the book - "The Formula of Beauty." There were new, previously unpublished novellas "The Formula of Beauty" and "The Landing of the Soul". In these stories, the author recalls his youthful hobbies, talks about love and affection for his native nature, reflects on what beauty is. In an interview with one of the Irkutsk newspapers, Vladimir Pavlovich said:

“Beauty is the harmony of diversity, precisely harmony, if there is no harmony in diversity, this is not beauty. This is only the physical part of the so-called beauty, and spiritual beauty is the pursuit of the ideal. "

The book contains these components ...

It is impossible to achieve the ideal, but it is necessary to strive for it, otherwise our life will become meaningless. "

At the very end of 1999, or rather, on December 30, Vladimir Maksimov published a new collection of poems "My Sister Autumn ...", which incorporated poems written in the period from 1965 to 1998. He said about the release of this book:

“I rarely write poetry. From time to time. That is why I do not consider myself a professional poet ... I am very glad that this book will be published, because it reflects a large part of my life, and, consequently, the era, in a poetic form. "

Like the previous book, "Autumn for my sister ..." was designed by the artist Irina Tsoi in autumn colors.

“Having said goodbye without regret this summer,

I met autumn, joyfully and simply,

As a best friend

I have not met

I have many long gray boring days ...

Opening him

Hugs, heart, soul

Taking out the wine

I began to listen diligently

His story:

About wanderings and countries

About different cities, about the oceans.

How a long way is looped

That there is not even a minute to rest.

What's farther and farther south again

For hundreds of countries. Over the distant seas ...

All this was told to me by a fresh wind.

Thank you, autumn, that you are in the world! "

The book was well received by Irkutsk readers and fellow writers. But, perhaps, the author himself said the best about his poetry in the poem that precedes the collection:

My quiet poetry -

Like a gentle rustle of a breeze

Like a leaf mad in late autumn

In the disturbing light of the lighthouse ...

Like a kind of sad wet, dark

Without leaves, branches of poplars.

And carried away by the wind, by the cold

To the south of the last cranes ...

My low-key poetry -

Everything is watercolor and light

As in the north sea on an island

The smoke of someone else's fire ...

My little poetry -

Lightning touch!

May it remain in your memory

Let it thunder in the soul.

The poem "Angarsk" from this collection became a song about the city, the music for which was composed by Evgeny Yakushenko.

In 2004, the book "That Summer ..." was published, composed of two prose cycles: "Baikal Tales" and "Days of Our Life".

Maximov defined the genre of the book as “ narration in stories, novellas, short stories, connected by the unity of place"And explained that he" traveled so much on earth, visited the seas and oceans and saw many beautiful places: Sakhalin and Ossetia, the Kuriles and the Carpathians, the volcanoes of Kamchatka and the fresh snowy to unnaturally clean peaks of Sikhote-Alin, neat Estonian landscapes with their fluffy white mists over the bogs and the White Sea abandoned villages in their sunset and harsh beauty, and the Transbaikal sad yellow distant steppes; blown, blown, blown by the winds of White, Black, Baltic, Caspian, Bering. Of the Sea of Japan, the Sea of Okhotsk and the Pacific Ocean ”I decided to choose from all this mosaic of places a small village in which the action of“ Baikal Tales ”takes place.

« I want to devote this story, if I have the strength to write it to the end, to the proud transparent - white - blue Baikal rocks visible on the other side; its waters, not affectionate, but drawing to themselves with their deep purity; its fresh winds, bringing vigor and joy; large emerald - blue pieces of ice of stars above it; eerily transparent, wind-polished ice and a small village where I was always so good and calm, like in no other place. And where more than once at nights I listened to the smoothly-measured breathing of the waves, hiding behind a sheepskin-smelling sheepskin coat in the hayloft and looking, unable to tear myself away, into the mesmerizing abyss of the black sky, guessed only because of the stars and looking, like in a mirror, at Baikal. And where only one night, in the same hayloft, I overheard the plaintive tired sighs of the autumn wind, perhaps from somewhere from a high plateau located near Mount Kinabalu on the island of Kalimantan and the Indian Ocean ...

It was then, when the wind seemed to pass through me, I tangibly felt that I was just a particle of an immensely vast world, a particle of this wind and, at the same time, I was the entire Cosmos ... Memories that had not yet happened, blurred like watercolors, came to life and merged with me. And then it seemed to me that I understood what the wind was crying about ...

He grieved for everything and for everyone: for the planet on which he was born, and for us, who live on the planet - for everyone, from the ant to the person. And that he is alive only as long as the Earth is alive and inviolable. And about his eternity, which is such an unbearably heavy burden ...»

Maksimov managed to convey to the reader the sincerity of feelings, the joy of communicating with nature, the book is distinguished by the originality of the language, the persistent desire to see the light in life and tell it to the reader. The pages that talk about underwater research on Lake Baikal, in which the author was a participant, are read with great interest.

In 2005, the publishing house "Irkutsk Writer" published the book "Don't Look Back", the genre of which V. Maksimov defined as a novel - a parallel. Why parallel? There are two main characters in the novel: Igor Vetrov, who lives and acts in real time, and Oleg Sanin, unknown to Igor, whose diary Vetrov found in the attic of the hunter's house, where he lived for some time while in practice. At first glance, the heroes, their actions are similar, but only at first glance. Vladimir Kornilov, a poet from Bratsk, who studied at the same time as V. Maksimov at the Literary Institute, wrote a review "Taiga Marked Fates" (Reflections on Vladimir Maksimov's novel "Don't Look Back"). The review was published in the weekly "Tvoya Gazeta" (g.). Without elevating or pleading for the novel's merits, Kornilov gave, in our opinion, an objective assessment of the book. He noted that it was written in a pure, poetry-filled language that retained the expressive Russian dialect. Concluding his reflections, Vladimir Kornilov writes:

« Closing the book, I still cannot part with its heroes, with these spiritually generous people devoted to romance. As if all these years in the same team I wandered with them through the wild taiga places, which left an indelible mark in their fates, together they froze and wandered through the snow, shared the last biscuit like a brother ...»

Most of the readers who got acquainted with this novel share the opinion of V. Kornilov, noting the artistic expressiveness, masterful descriptions of nature, as well as the moral searches and experiences of the heroes.

In March 2007, the publishing house "Irkutsk Writer" published a collection of poems by V. Maksimov "In Memory of a Sunny Bunny".

« This book is very personal and is dedicated to the memory of parents who recently passed away. And a person, no matter how old he is, after the loss of his parents feels his orphanhood on this earth. That is why many of the poems of this collection are very sad, imbued with reflections on life and death, on the phenomenon of time. And I thought that this book would be, so to speak, for a small circle of readers: relatives and friends.", - says V. Maksimov.

But the poems of this collection about childhood, youth, first love turned out to be interesting and not only to relatives and friends, Vladimir Pavlovich was repeatedly convinced of this at meetings with readers in the libraries of Irkutsk and the region.

On the eve of the anniversary, the publisher G. Sapronov, known not only in Irkutsk, but also in Russia, prepared a book by V. Maksimov "Premonition of Miracles". It consists of a story and ten stories that were written, unlike others, in the 21st century. Like all books published by G. Sapronov's publishing house, the book is printed with high quality. The stories included in the collection tell about our contemporaries who had to live in an era of change, and on whom these changes were reflected in different ways. In the preface to the book V. Maksimov writes:

«... I'm interested in an ordinary person, who is a unit of the scale of the universe. His mental attitude, his worries, experiences, his love ... And since our life, of any person in itself is a unique miracle, often not perceived by us as such, I wish all of you all kinds of miracles, hoping that the book is not will seem boring to you and that after reading it, you will not leave the premonition of a miracle at least for some time».

Life poses many problems and questions for the heroes of V. Maksimov, they strive to make it better, fairer and more beautiful to the best of their understanding. It doesn't always work out. But when reading this book, as well as the earlier ones, the feeling of light sadness does not leave, perhaps it should be so, because according to the definition of another of our fellow countrymen, L. Borodin, there is no miracle without sadness.

Vladimir Pavlovich is a laureate of several regional journalistic prizes, in 2001 he was awarded a diploma of the Ministry of Railways and the Secretariat of the Union of Writers of Russia "For literary coverage of the problems of the Transsib". He is a frequent visitor to the libraries of our city and region, our readers remember these meetings, because they give a meeting with an amazing person who is in love with Siberia, its nature and, of course, Siberians, they bring to those present not only light sadness, but charge with good energy, inherent in the writer.

P.S.

In 2008, the publishing house of Sapronov published a new book by V. Maksimov "Premonition of Miracles". This book is light prose telling about real events and destinies. With the heroes of the book you will visit the Kuriles and Commanders; in the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Japan; on the banks of the Dniester and Kamchatka; in old and very young cities.

Literature

- Formula of beauty. The story. Stories. Irkutsk, 1998.

- Do not look back. A parallel novel. Irkutsk, 2005.

- Premonition of miracles. Story, stories. Irkutsk, 2008.

- Where does all this disappear? .. Story, stories. Irkutsk, 2010.

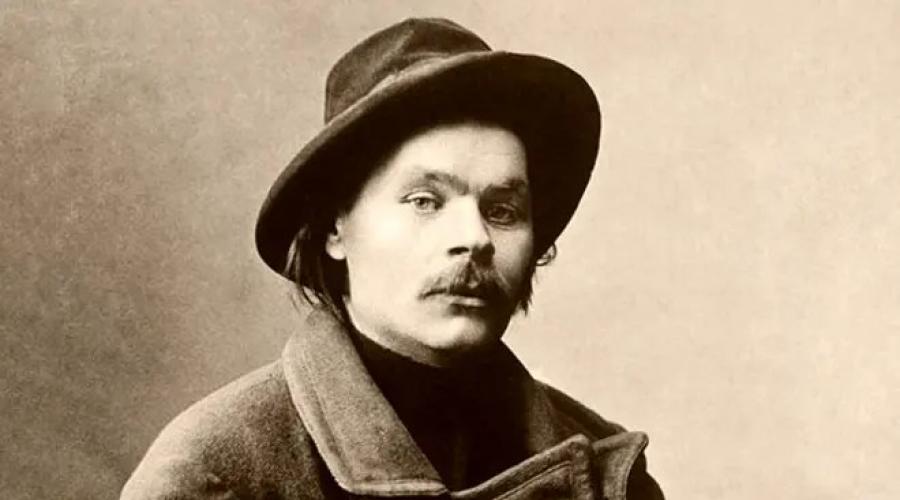

Alexey Peshkov, better known as the writer Maxim Gorky, is a cult figure for Russian and Soviet literature. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize five times, was the most published Soviet author throughout the entire existence of the USSR and was considered on a par with Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin and the main creator of Russian literary art.

Alexey Peshkov - the future Maxim Gorky | Pandia

He was born in the town of Kanavino, which at that time was located in the Nizhny Novgorod province, and now is one of the districts of Nizhny Novgorod. His father Maxim Peshkov was a carpenter, and in the last years of his life he ran a steamship office. Vasilievna's mother died of consumption, so Alyosha Peshkova's parents were replaced by Akulina Ivanovna's grandmother. From the age of 11, the boy was forced to start working: Maxim Gorky was a messenger at a store, a barman on a steamer, an assistant to a baker and an icon painter. The biography of Maxim Gorky is reflected by him personally in the stories "Childhood", "In people" and "My universities".

Photo of Gorky in his youth | Poetic portal

Photo of Gorky in his youth | Poetic portal After an unsuccessful attempt to become a student at Kazan University and arrest due to his connection with a Marxist circle, the future writer became a watchman on the railway. And at the age of 23, a young man goes to wander around the country and managed to get to the Caucasus on foot. It was during this journey that Maxim Gorky briefly wrote down his thoughts, which would later become the basis for his future works. By the way, the first stories of Maxim Gorky also began to be published around that time.

Alexey Peshkov, who took the pseudonym Gorky | Nostalgia

Alexey Peshkov, who took the pseudonym Gorky | Nostalgia Having already become a famous writer, Alexey Peshkov leaves for the United States, then moves to Italy. This happened not at all because of problems with the authorities, as some sources sometimes present, but because of changes in family life. Although abroad, Gorky continues to write revolutionary books. He returned to Russia in 1913, settled in St. Petersburg and began working for various publishing houses.

It is curious that for all his Marxist views, Peshkov was rather skeptical about the October Revolution. After the Civil War, Maxim Gorky, who had some disagreements with the new government, went abroad again, but in 1932 he finally returned home.

Writer

The first of the published stories by Maxim Gorky was the famous "Makar Chudra", which came out in 1892. The two-volume "Essays and Stories" brought fame to the writer. It is interesting that the circulation of these volumes was almost three times higher than usually accepted in those years. Of the most popular works of that period, it is worth noting the stories "Old Woman Izergil", "Former People", "Chelkash", "Twenty Six and One", as well as the poem "Song of the Falcon". Another poem "The Song of the Petrel" has become a textbook. Maxim Gorky devoted a lot of time to children's literature. He wrote a number of fairy tales, for example, "Sparrow", "Samovar", "Tales of Italy", published the first special children's magazine in the Soviet Union and organized parties for children from poor families.

Legendary Soviet writer | Kiev Jewish community

Legendary Soviet writer | Kiev Jewish community The plays by Maxim Gorky "At the bottom", "Bourgeois" and "Yegor Bulychov and others", in which he reveals the talent of a playwright and shows how he sees the life around him, are very important for comprehending the work of the writer. The stories "Childhood" and "In People", the social novels "Mother" and "The Artamonovs Case" are of great cultural significance for Russian literature. The last work of Gorky is considered the epic novel "The Life of Klim Samgin", which has the second name "Forty Years". The writer worked on this manuscript for 11 years, but did not manage to finish it.

Personal life

The personal life of Maxim Gorky was rather stormy. For the first and officially only time, he got married at the age of 28. The young man met his wife Yekaterina Volzhina at the publishing house "Samarskaya Gazeta", where the girl worked as a proofreader. A year after the wedding, a son, Maxim, appeared in the family, and soon a daughter, Catherine, named after her mother. Also in the upbringing of the writer was his godson Zinovy Sverdlov, who later took the surname Peshkov.

With his first wife Yekaterina Volzhina | Livejournal

With his first wife Yekaterina Volzhina | Livejournal But Gorky's love quickly disappeared. He became burdened by family life and their marriage with Ekaterina Volzhina turned into a parental union: they lived together exclusively because of the children. When little daughter Katya died unexpectedly, this tragic event became the impetus for the breaking of family ties. However, Maxim Gorky and his wife remained friends and corresponded until the end of their lives.

With his second wife, actress Maria Andreeva | Livejournal

With his second wife, actress Maria Andreeva | Livejournal After parting with his wife, Maxim Gorky, with the help of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov, met the actress of the Moscow Art Theater Maria Andreeva, who became his de facto wife for the next 16 years. It was because of her work that the writer left for America and Italy. From previous relationships, the actress left a daughter, Catherine, and a son, Andrei, who were raised by Maxim Peshkov-Gorky. But after the revolution, Andreeva became interested in party work, began to pay less attention to the family, so in 1919 this relationship came to an end.

With third wife Maria Budberg and writer HG Wells | Livejournal

With third wife Maria Budberg and writer HG Wells | Livejournal Gorky himself put a point, saying that he was leaving for Maria Budberg, the former baroness and concurrently his secretary. The writer lived with this woman for 13 years. The marriage, like the previous one, was unregistered. The last wife of Maxim Gorky was 24 years younger than him, and all her acquaintances were aware that she was "spinning novels" on the side. One of the lovers of Gorky's wife was the English science fiction writer Herbert Wells, to whom she left immediately after the death of her de facto husband. There is a great chance that Maria Budberg, who had a reputation as an adventurer and unambiguously collaborated with the NKVD, could be a double agent and also work for British intelligence.

Death

After his final return to his homeland in 1932, Maxim Gorky works in publishing houses of newspapers and magazines, creates a series of books "History of Factories and Plants", "Library of the Poet", "History of the Civil War", organizes and conducts the First All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers. After the unexpected death of his son from pneumonia, the writer wilted. At the next visit to the grave of Maxim, he caught a bad cold. For three weeks Gorky had a fever that led to his death on June 18, 1936. The body of the Soviet writer was cremated, and the ashes were placed in the Kremlin wall on Red Square. But first, the brain of Maxim Gorky was removed and transferred to the Research Institute for further study.

In the last years of his life | Digital library

In the last years of his life | Digital library Later, the question was raised several times that the legendary writer and his son could have been poisoned. People's Commissar Genrikh Yagoda, who was the lover of Maxim Peshkov's wife, was involved in this case. Also suspected of involvement and even. During the repressions and the consideration of the famous "Doctors' Case", three doctors were accused of including the death of Maxim Gorky.

Books by Maxim Gorky

- 1899 - Foma Gordeev

- 1902 - At the bottom

- 1906 - Mother

- 1908 - The life of an unnecessary person

- 1914 - Childhood

- 1916 - In people

- 1923 - My Universities

- 1925 - The Artamonovs case

- 1931 - Yegor Bulychov and others

- 1936 - The Life of Klim Samgin

Maximov

Vladimir Emelyanovich

(Samsonov Lev Alekseevich)

(1930-1995)

Writer, publicist, editor.

Born in Moscow in the family of a worker who was repressed in the 30s. He changed his last name and first name, ran away from home, was homeless, was brought up in orphanages and colonies for juvenile delinquents, from where he constantly escaped to Siberia, Central Asia, and Transcaucasia. He was convicted on criminal charges and spent several years in camps and exile. After his release in 1951, he lived in the Kuban, where he first began publishing in newspapers and published a collection of very mediocre poems.

The impressions of these years formed the basis of the first publications: "We are making habitable the earth" (Sat. "Tarusa pages", 1961), "A man is alive" (1962), "Ballad of Savva" (1964), etc. In 1963 it was adopted to the Union of Soviet Writers. The novels "Quarantine" and "Seven Days of Creation", which were not accepted by any publishing house, were widely circulated in Samizdat. For these novels, their author was expelled from the Writers' Union and placed in a psychiatric hospital. In 1974 Maksimov was forced to emigrate. Lived in Paris.

In 1974 Maksimov founded the quarterly literary, political and religious journal Continent (see vol. 3, p. 265), of which he remained the editor-in-chief until 1992.

In exile, he wrote "The Ark for the Uninvited" (1976), "Farewell from Nowhere" (1974-1982), "Look into the Abyss" (1986), "Wandering to Death" (1994), etc.

The most complete editions:

Collection in 6 volumes, Frankfurt am Main: Sowing, 1975-1979;

Collected works in eight volumes, M .: "TERRA" - "TERRA", 1991-1993;

Vladimir Maksimov is a famous Russian writer. Also known as an editor and publicist.

Biography of the writer

Vladimir Maksimov was born in 1930. He was born in Moscow. His father was a simple worker. According to one version, he went missing during the Great Patriotic War, according to another, he fell under the Stalinist repressions of 1937 on charges of Trotskyism.

The name of the writer at birth was Lev Alekseevich Samsonov. In adolescence, he had a rebellious character. He grew up without a father, his mother could not cope with him. In his youth, Vladimir Maksimov ran away from home. He lived on the street as a homeless child, due to the fact that he changed his name and surname, his relatives could not find him. As a result, the future prose writer was brought up in orphanages. He ended up in colonies for juvenile delinquents, from where he regularly escaped. He was hiding all over the country - in Central Asia, Siberia and Transcaucasia.

At the age of 16, he received 7 years in prison for a combination of crimes, but was soon released for health reasons. Once free, he worked at construction sites and on expeditions in the Far North and Siberia. In the end he settled in the Kuban, getting a job in the agricultural artel "Krasnaya Zvezda" as a collective farmer.

The first literary experiments

Vladimir Maksimov began to write poetry in the 50s. In 1952 it was first published in the Soviet Kuban newspaper. From the 54th he lived in the city of Cherkessk in the Stavropol Territory. Here he has already taken up journalistic work. He worked on radio and in local print media.

His first collection of poetry was published in Cherkessk. It was called "Generation on the Watch". It includes poems, poems and even translations of North Caucasian authors. The book was not successful.

To continue self-education, Vladimir Maximov moved to Moscow. Here he took up literary daily work, wrote articles and essays for newspapers and magazines, translated poems of poets of the Soviet republics.

"We are settling in the land"

The first significant work Maksimov Vladimir Emelyanovich published in 1961. In the almanac "Tarusa Pages" his story "We are making habitable the earth" was published. Around the same time, another of his novellas, "A Man Is Alive", appeared in another literary magazine.

Maksimov's heroes had an unusual fate, while they lived uncomfortably and restlessly. They looked like most Soviet citizens, but did not at all resemble the characters in other works of that time. Much of these stories were autobiographical.

These works were highly appreciated, in particular by Paustovsky and Tvardovsky. In 1963, Vladimir Maksimov was admitted to the Union of Writers of the USSR. The biography of the prose writer was further associated exclusively with literary creativity.

Writer in opposition

Moreover, Maksimov himself, like many heroes of his works, was opposed to what was happening around him, did not fit well into Soviet reality. This became especially evident in the early 70s. In his articles and letters, he criticized the system and the existing government. These texts were distributed exclusively in samizdat. Also published in émigré publications abroad.

During this period, two of Maksimov's novels were published abroad: "Quarantine" and "7 Days of Creation". They criticize the Soviet society, a Christian orientation is clearly expressed. These publications led to the author's final break with the authorities. In 1973, Vladimir Maksimov was expelled from the Writers' Union. The author's photo no longer appeared in the official Soviet press.

Finding himself out of business at home, the prose writer became more and more popular in the West.

Emigration

In 1974, Maksimov and his wife were allowed to leave for France for one year. But he left the country for good, as shortly before that he received a summons demanding to come for a medical examination of his mental health condition. At that time, this could threaten with compulsory confinement to a psychiatric clinic.

In Paris, Maximov came to life. He began to write a lot. Two novels created in exile stand out in particular. These are "The Ark for the Uninvited" and "Look into the Abyss".

The first reveals the image of the Soviet Generalissimo Stalin through the contrast between his everyday routine and natural disasters caused by his politicians. In the second, written in 1986, through a romantic story, the fate of the participant in the Civil War, Admiral Kolchak, was shown.

Continent magazine

The most ambitious work of Maksimov in France was the release of the magazine "Continent". He worked on this émigré edition for about twenty years.

Thus, the release of "Continent" became a kind of continuation of the tradition of publishing a periodical about the problems in Russia abroad. The first sign was Herzen's "Bell".

Maksimov's magazine clearly and fairly described the domestic reality, talked about what could not be mentioned in the pages of the Soviet press. Moreover, in many ways it was a literary magazine. Therefore, he was often compared with Pushkin's Contemporary and Nekrasov's Notes of the Fatherland. Both in these publications and in the Continent, the novelties of modern prose and poetry were socially significant texts that stimulated society to an active civic position, reflecting the main problems of Russian society at that time.

Vladimir Maksimov is a writer who managed to create a more progressive publication than even Tvardovsky's "New World", which nevertheless came out in the USSR in conditions of strict limitations in the choice of topics and their coverage. Only in this way was it possible to confirm the legitimacy of the definition of the intelligentsia as a concept that means a part of society that is able to think freely and express its views on any issues.

At the same time, among the progressively minded part of Soviet society, there were many who were critical of the publication of the magazine "Continent". Among them was the famous writer, Nobel Prize laureate in literature, Alexander Solzhenitsyn. By the way, a native of the "New World". He criticized the brainchild of Maximov for being too cautious, trying to become a compromise on many issues.

Return to Russia

After the collapse of the USSR, Vladimir Maksimov began to visit his homeland. At the same time, the biography of the writer remained connected with abroad until the last years of his life. In the 90s he himself began to periodically come to Russia. However, even at this time, he was very skeptical and critical of the existing government and what was happening in the country in order to find understanding among those in power. The only thing that has changed dramatically is access to his works. Nobody forbade printing and publishing them at home anymore.

Many were surprised and outraged by his publication in Pravda. Hotheads even managed to accuse the writer of unscrupulousness. After all, he has always been known for his anti-communist sentiments. And here he spoke in the opposite way. Not everyone understood that the main thing for Maksimov was not the existing political system, but patriotism and concern for the true welfare for their homeland. His publicistic articles and essays, with which he began to appear regularly on the pages of the media in the 90s, were devoted exclusively to protecting the interests of the Russian people. And nothing else.

At this time, his most famous works were republished in Russia, even the complete collection of the author's works in eight volumes was published. And in 1992 at the Mayakovsky Theater was staged a play based on Maximov's play entitled "Who's Afraid of Ray Bradbury?"

Death of the prose writer

Soviet citizenship, which Maximov was deprived of after emigrating abroad, was promptly returned to him back in 1990. In the last years of his life, he began to come to Russia more and more often and stay for longer periods. For a long time at this time he lived in Moscow. He strongly counted on democratic transformations in society and on the fact that the face of Russia would radically change.

The harsh reality around him showed him and everyone else that these hopes were premature and in vain. In his public speeches and articles, the theme of disappointment, pessimism, and disbelief in the bright future of Russia was increasingly seen.

He died in 1995 in Paris.

The name of Vladimir Maksimov was reintroduced into literary criticism and readership in the second half of the 80s of the XX century. Even according to the first negative assessments of Maksimov, the “leftists” could understand that the worldview and work of the writer clearly did not fit into the liberal system of values. Discrediting the writer was carried out at the level of casually thrown facts or alleged facts. Among them, the most frequently mentioned were the "Stalinist" poems of Maximov.

The accusers, led by Vitaly Korotich, of course, did not recall the "toast" to Stalin written by AAkhmatova, B. Pasternak, O. Mandelstam. They did not remember "The Ballad of Moscow" and "At the Great Grave" by A. Tvardovsky, "How You Teached" and "Friendship" by KSimonov, "Memorable Page" and "Great Farewell" by SMarshak and many other works of a similar orientation. They did not pay attention to the fact that V. Maksimov, in contrast to the named authors, was practically a young man at the time of writing the "seditious" poems.

Arybakov in the article “From Paris! Clear?!" ("Literaturnaya Gazeta", 1990, No. 20) cited other facts from the biography of Vladimir Yemelyanovich, designed to discredit him. According to Arybakov, in the article "Relay Race of the Century" Maksimov supported the "pogrom" organized by Khrushchev of the intelligentsia in March 1963. And as a result, according to Rybakov, "in October 1967 Kochetov made Maksimov a member of the editorial board of the magazine - zeal should be rewarded." Rybakov also argued that the management work in the magazine "October" went to V. Maksimov's benefit - it came in handy in the "Continent".

Similar accusations against V. Maksimov sounded before. One of the questions to the writer Alla Pugach was revealingly formulated: “I would risk causing displeasure, but you are often remembered<...>participation in the editorial board of the Kochetovsky "October" ("Youth", 1989, No. 12). Maksimov's answer contains a statement of a fact that explains a lot: “And I myself left the editorial board of Oktyabr after 8 months, when I saw that I could not influence at least prose in any way. But which of them did it? "

Returning to Rybakov's publication, I would like to note his obvious bias: Anatoly Naumovich left out of the brackets of his article the meager period of Vladimir Yemelyanovich’s stay in Oktyabr. In addition, someone who Rybakov knew very well that a member of the editorial board in a magazine most often does not decide anything and, moreover, does not lead. And in general, some kind of delayed reaction in Vs. Kochetova: I dragged on for four and a half years with gratitude ... The assertion of the author of Children of the Arbat: Maksimov is the foam of “Russian foreign literature” - there is no need to comment on it.

Attacks on Vladimir Maksimov from V. Korotich, Arybakov, Elkovlev and other rassadins were also caused by the fact that for a long time Vladimir Yemelyanovich was perceived by many “leftists” as their own or almost theirs. There were formal and informal prerequisites for this.

In the 60s, among the writers-friends of Maximov, the "left" prevailed significantly. It is no coincidence that A. Borschagovsky, MLisyansky, R. Rozhdestvensky were recommended to the Writers' Union of Vladimir Yemelyanovich. And the appeal in defense of the AGinzburg "group" 5 years later Maksimov signed together with L. Kopelev, Vaksenov, B. Balter, V. Voinovich, L. Chukovskaya, B. Akhmadulina ... from the USSR in 1974, the writer became the head of the "Continent" - that is, he received the blessing of the CIA for this position. And yet, it was in the emigration that Maksimov's obvious “Russification” began, disagreements and conflicts with many “leftists” arose.

In this regard, they often recall the story of Andrei Sinyavsky, allegedly expelled by Maximov from the "Continent". Andrey Donatovich is an iconic figure in the world in which Vladimir Yemelyanovich had to "cook" almost his entire creative life. Through Terts-Sinyavsky, both Maksimov himself and the “left” intelligentsia (in the emigration and the Soviet Union), and the main reason for their disagreements, more precisely, Rhesus incompatibility, are "more visible".

Vaksenov, in response to the death of A. Sinyavsky "In Memory of Terts", expressed his attitude towards Andrei Donatovich and the country, an attitude so characteristic of the majority of the "left". I will cite only a small excerpt from Vaksenov's fake and vicious verdict: “It will not be easy for Russia to plead guilty to Sinyavsky. In his fate, she revealed to the full extent and depth all her "abyss of humiliation." This, by his own definition, "motherland-bitch" revealed in his early student years an exceptional talent, an extraordinary mind, began to "work" with him, that is, to defame in the most vile way ... "(V. Aksenov, Zenitsa Oka. - M ., 2005).

V. Maksimov repeatedly denied such accusations against Russia, emotionally convincingly showed their groundlessness and absurdity. He, like the most diverse authors, was unacceptable to identify the USSR and Russia. Vladimir Yemelyanovich said more than once that he fought with an ideology, a system, and not a country. This fundamentally distinguished him from Russophobes of all stripes - from dissidents to Soviet officialdom headed by Alexander Yakovlev. Moreover, Maksimov, an anti-communist, spoke with respect of those communists who did not run away from the party at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s (Yunost, 1991, No. 8).

In the aforementioned essay, V Aksenov calls ASinyavsky and Yu Daniel "a symbol of struggle and even victory." L. Borodin in his book of memoirs "Without a Choice" (Moscow, 2003) evaluates his fellow prisoners differently.

Julius Daniel, by definition of Leonid Ivanovich, "soldier", which, according to the terminology of the author of the memoirs, means "the highest assessment of human behavior in captivity." Borodin perceived Sinyavsky in a fundamentally different way. For his indifferent and pragmatic attitude to a person, Andrey Donatovich was called a “cannibal”, a “consumer of people” in the camp. The idol of the liberal intelligentsia and in the zone "lived among people, not with people", "every person was interesting to him only until the time when interest was not exhausted."

Asinyavsky, according to Aksyonov, “a fighter and even a winner of the regime”, in the camp for exemplary behavior (and it also included attending political classes, which all political classes, with the exception of the “Sinyavtsy”, refused at the cost of a punishment cell and hunger strikes) received a thug job »- a cleaner in a furniture shop. According to Borodin, "none of the political prisoners would go to such work even on orders."

ASinyavsky's disgusting words "Russia is a bitch", which Vaksenov and the majority of the "left" liked, and for which at least you need to beat the face, are a revealing illustration of Abram Tertz's usual attitude to the Motherland. And in the camp, as a devout "leftist", according to Borodin, he scolded Russia and the Russians with ease and joy, with extraordinary rudeness, and was very reverently obsequious towards the Jews, which sometimes took comic forms. I will cite an excerpt from L. Borodin's memoirs: “... For the sake of a Jew by religion Rafailovich,“ the whole honest company ”sat down in the dining room, without taking off their dirty camp hats with ribbons, almost floating in plates. I am not even talking about unkempt and unwashed beards. I called aside the "Shurik" serving Sinyavsky's company and said: "Listen, explain to our Russian intelligentsia, those at the table, that if you are consistent, you need to mature even before circumcision."

My rudeness worked. They all took off their caps. "

Leonid Borodin, who served in camps and prisons for 11 years (I remind those who groan about “sufferers” like Joseph Brodsky and Andrei Sakharov), ends his memoirs symbolically, in Russian: “About myself, I can say with clear confidence that I was lucky, happiness fell - in the years of troubles and trials, personal and national - neither in words nor in thoughts could I be defiled by the curse of the Motherland. " ASinyavsky, like most of the representatives of the third wave of emigration, made a career for himself on this desecration ...

The theme of the relationship between Maksimov and Sinyavsky in "Continent" repeatedly arises after the death of Vladimir Yemelyanovich. So, in June 2006, to the question: "... What was the immediate reason for ASinyavsky's resignation from the editorial board of the" Continent "?" - Natalya Gorbanevskaya, who knows the situation from the inside, did not answer. However, she clearly stated that the gap occurred on the initiative of Sinyavsky, who did not clearly explain his choice.

The following fact characterizes the “dictator” Maksimov is interesting. Bukovsky and Galich, convinced that Vladimir Yemelyanovich was to blame for the conflict, tried to intercede for Sinyavsky and resolve the problem. According to N. Gorbanevskaya, the reaction of the editor-in-chief of the Continent stunned Bukovsky and Galich: “Please,” said Maksimov, “I highlight 50 pages in the Continent, a“ free rostrum ”edited by Andrei Sinyavsky, and I don’t interfere, not a single comma throne. And in addition - outside of these 50 pages - I am ready to publish any articles by Sinyavsky "(" Voprosy literatury ", 2007, No. 2).

Andrey Donatovich refused such a generous offer. He refused, I think, because, firstly, he wanted and could only be the first, the only one, and secondly, he was perfectly aware of his incompatibility - human and creative - with Maximov.

It was the attitude to Russia that determined the conflict between Vladimir Maksimov and A. Sinyavsky, Vaksenov, F. Gorenstein, V. Voinovich and other “leftists”. Moreover, in contrast to the overwhelming majority of representatives of the third wave of emigration, V. Maksimov perceived his life outside his homeland as a misfortune. In the very first interview given to a journalist from the USSR, Vladimir Yemelyanovich admitted that he lost more abroad than he gained, and assessed his inner state as very bad (Yunost, 1989, no. 12). Love for the Motherland outweighs for Maximov freedom, editorial and writing success, material benefits and other advantages of living abroad.

Emigration, editing of the "Continent", a tough and cruel struggle of ideas and ambitions, a rare concentration of mutually exclusive authorities on the narrow site of the magazine, and other things taught Maksimov to remain himself in any circumstances, to be one warrior in the field.

Since the beginning of perestroika, Maksimov, who always felt that he was a part of the people, the country, closely followed the events taking place, taking everything to heart. He, who knew the "civilized" world firsthand, tried to save from possible mistakes, to dispel many illusions.

In the article "We are elevated by deception" ("Literaturnaya gazeta", 1990, No. 9) V. Maksimov not only asserts that freedom of speech in the West is a myth, but also raises his hand against the "holy of holies": "Democracy is not a choice the best, but the choice of their own kind. " A year later, in a conversation with Alla Pugach, he talks about the deformities of the "civilized" world and, in solidarity with the well-known thought of Igor Shafarevich (who was at that time one of the most powerful irritants for the "left"), asserts: "... And one and the other path, in general, leads to the same social and spiritual cliff "(" Youth ", 1991, no. 8).

V. Maksimov immediately and accurately assessed T. Tolstaya, A. Nuikin, B. Okudzhava, A. Boznesensky, Art. Rassadin and all those who claimed and are still claiming the role of ideological and cultural leaders. "Looting naughty" he calls them in an article with the same name and characterizes, in particular, as follows: flirting matron (T. Tolstaya. -Yu.P.) means anyone but himself. Whom? Of course, the "enemies of perestroika", that is, those who prevent people like her from powdering the brains of their foreign listeners with impunity<...>.

"Enemies of perestroika" every day more and more sounds like "enemies of the people." Atu them! It is not possible to defame, and it is not a sin to soak it "(" Continent ", 1989, no. 1).

Four years later, V. Maksimov's forecast came true. True, on the conscience of the "superintendents of perestroika", the signers and non-signers of the famous letter of 42, not only the blood of the innocent victims of October 1993, but also those tens of millions who died prematurely as a result of "reforms" engendered or blessed by the "marauding mischievous ".

Despite all that has been said, there was no unified attitude of the "left" to Maksimov at the turn of the 1980s-1990s. While some immediately began to “kill” Vladimir Emelyanovich, others still hoped to return him to their camp. It is significant who and how met the writer during his first visit to his homeland. So, according to the memoirs of Pyotr Alyoshkin, on April 10, 1990 at the airport of Vladimir Emelyanovich, “only a few people from the magazines Oktyabr, Yunost, the writers Addis, Krelin, Konchits, were waiting for me” (Literary Russia, 1995, No. 13). And at the banquet in the restaurant "Prague", according to Igor Zolotussky, there were only "friends". “Then these“ friends ”began to dissipate, because Volodya, contrary to the“ party ”etiquette, began to meet with Rasputin, Belov, and even visited (my detente - Yu.P.) Stanislav Kunyaev. They already began to look askance at him, asking: why are you doing this? After all, they are red-brown ”(I. Zolotusskiy On the stairs at Raskolnikov's. - M., 2000).

V. Maksimov has repeatedly stated that he, outside of the struggle, over the struggle, does not accept group approaches and treats each person and phenomenon specifically and individually. And this is really so. However, something else is also obvious: most of the statements and assessments of Vladimir Yemelyanovich in the last years of his life sound in unison with the most sensational articles of "right-wing" critics. I will give two examples, as if taken from the articles “We are changing? ..” by V. Kozhinov and “Essays on literary customs” by V. Bondarenko.

In a letter dated November 26, 1987 to Alexander Polovets, Vladimir Emelyanovich calls Vitaly Korotich and Andrei Voznesensky "Soviet crooks from literature" and as one of the evidence he cites the book of the first about America "The Face of Hatred", published "only four years ago" ("Questions Literature ", 2007, No. 2). And in a conversation with Lola Zvonareva V. Maksimov characterizes two active “perestroika” as follows: “I hate to hear from Okudzhava, a former member of the CPSU for more than thirty years, his new anti-communist manifestos. Immediately I want to ask: "What have you been doing there for thirty years?" And Borschagovsky? He presided over the meeting, which kicked me out of the Writers' Union, calling me a "literary Vlasov", and now I am "red-brown" for him. It is difficult to calmly observe how people change once again together with their superiors "(Literaturnaya Rossiya, 1995, No. 1-2).

Maksimov could not and did not want to adapt to the democratic times and customs. From a "right-wing" position, he has repeatedly spoken out on the explosive national question. Already in his first interview with a Soviet journalist from a "left" publication, the national movements in Georgia and Latvia, which were welcomed and supported by the liberals in every possible way, were called chauvinistic by Vladimir Yemelyanovich (Yunost, 1989, no. 12). And his statement from another interview even today, when the opening of museums of occupation is in vogue in the former republics of the USSR, sounds relevant: “... And when, say, Georgian patriots talk about occupation, I answer them: we can purely political sense. Its ideological leader was Ordzhonikidze, and the military was Kikvidze. And they were greeted with open arms by generally not the worst representatives of the Georgian people - Okudzhava, Orakhelashvili, Mdivani. And Georgia was ruled by Georgians for all seventy years.<...>And in the same “enslaved” Georgia, not a single person - not only Russian - could occupy positions of responsibility ”(“ Moscow ”, 1992, No. 5-6). Maksimov's version of the "occupation" of Poland, the Czech Republic, the Baltic states also does not coincide with the currently fashionable primitive false myths. Vladimir Yemelyanovich repeatedly insisted that all peoples took part in these events and that each people should take on a part of the common blame. To blame everything on the Russians, according to Maximov, is unfair and immoral.

Unlike the "left", Vladimir Yemelyanovich has always recognized Russophobia as a fact, as a phenomenon in our country and abroad. I will cite two short statements of the writer on this topic: “You are already a nationalist, if you only utter this word (Russia - Yu.P.). You are a chauvinist and a fascist "; “Yes, yes, it did not start today, not under Soviet rule. When Peter I died, all European courts openly organized festivities on this occasion.<...>... For them, Russia has always been a hostile state, a threat that must be destroyed and trampled down ”(“ Our Contemporary ”, 1993, No. 11).

When it was said all around that politics was a dirty business, Maksimov presented a code of honor that was outdated in the eyes of many to politicians and politicians. He applied it to absolutely everyone, including his main ideological opponents - the communists. At the same time, Vladimir Yemelyanovich did not welcome the closure of the Communist Party, because it expresses the opinion and interests of a part of the people, leaving which outside the political and social field is unfair and disastrous for society. Therefore, the writer called this act of Boris Yeltsin unworthy and so unusually summed it up: “It’s not even like a man” (“Moscow”, 1992, No. 5-6).

From a similar standpoint, Maksimov assessed the idea of a trial against the Communist Party, the idea of a new Nuremberg trial, which is still popular among liberal "thinkers" today. Then, according to the writer, Boris Yeltsin, and not only him, should be in the dock. “In that Nuremberg, ideology and its representatives were judged, which brought Germany to a deplorable state. And you want to get a good job - you want to surrender your membership cards and thereby cleanse yourself of the crimes to which you are most directly related! I don’t understand this and I will never be able to understand it ”(“ Moscow ”, 1992, No. 5-6).

Ironically, it was the Pravda newspaper that became for Maksimov one of the few tribunes in Yeltsin's Russia, where he got the opportunity to freely express himself on any issue. The liberal intelligentsia in the last years of the writer's life took a completely predictable position towards him.

Maksimov's departure from the "Continent" in 1992, the transfer of the magazine to Igor Vinogradov still raises questions. Right in the wake of the events, V. Bondarenko assessed the situation more accurately than others. In his article “Requiem for the Continent,” he, in particular, asserted: “Of course, it is monstrously difficult to kill your offspring, but I think the current compromise of Maksimov - the transfer of the magazine to Vinogradov - is a huge mistake. It was nevertheless necessary to close the Continent (The Day, 1992, No. 27).

After leaving the magazine, Vladimir Yemelyanovich, according to him, planned to gain a literary form, to more fully realize his creative "I". However, death prevented the implementation of the plan.

V. Maksimov wanted his return to the domestic reader to begin with the novel "Look into the Abyss." In this work, almost all the heroes, reflecting on the events of the revolution and the civil war, more than once express the idea: there were no guilty ones - everyone is guilty. As follows from the author's characteristics, numerous interviews and journalism of the writer, this is the position of V. Maksimov himself. She is often defined as Orthodox, with which it is difficult to agree. When everyone is equal - everyone is to blame, and no one is to blame - then there is no difference between good and evil, truth and lies, murderer and victim, traitor and hero, God and Satan. That is, such a system of values has nothing to do with Orthodoxy.

In general, in "To Look Into the Abyss", it would seem, directly according to the Bible, all the heroes are rewarded for their deeds. At the level of individual characters, there is a clear division into right and wrong, because only the latter are punished, which the author constantly emphasizes with the help of a repetitive compositional technique - "running ahead", when it is reported what kind of reckoning awaited this or that sinner.

In the novel, it is primarily rewarded to those who are directly or indirectly related to the death of Kolchak: from Lenin, "thinly-thinly" howling in Gorki in anticipation of death, to Smirnov, who fulfilled the leader's instructions on the spot. In addition, Smirnov's daughter and wife become victims of a kind of retaliation. Therefore, and not only for this reason, the ending of the chapter (not built on the author's word, according to the principle of assembling various documents and evidence), when for the first time in it openly declared the position of the writer ("That's it, good gentlemen, that's it!"), Does not sound like - Orthodox. Here and later in the novel, Maximov violates one of the main traditions of Russian literature, the tradition of Christian humanism. The death of any person or hero cannot be an object for irony, sarcasm, malicious satisfaction, etc. Maksimov's humor is akin to the humor of American and Jewish literature.

For deeds, it is also rewarded to heroes who were not involved in the death of Kolchak, but who sinned on other occasions. For example, about the sailors of Kronstadt, who brutally massacred the officers, the commandant, the governor-general in February 1917, without the same Orthodox attitude it is said:<...>sailor that after only four years at the same ditch they will be slaughtered like cattle by those who lured them onto this bloody path: as they say, he would have known where to fall, he would have spread straws, but it turned out to be tight at that time with such straw , oh, how tight! "

V. Maksimov has repeatedly expressed his admiration for the novel by B. Pasternak "Doctor Zhivago". This reaction, I think, is partly due to a similar approach to understanding the question of "man and time." In “Look into the Abyss”, as in “Doctor Zhivago,” through different heroes (Kolchak, Udaltsov, Timireva, others) and the author's characteristics, the idea of the insignificance and helplessness of a person before the force of circumstances, an avalanche of time is affirmed: “From the very beginning he ( Kolchak. -Yu.P.) doomed himself to this (death. -Yu.P.) deliberately. The circumstances prevailing in Russia by that time had no other outcome, just as there was no outcome for any daredevil who would have thought of stopping the avalanche at its very rapid ”; “This is not a riot, a cornet, this is a landslide, and, as you know, only a miracle can save you from a landslide ...”.

So, on the one hand, nothing and no one will save from an avalanche of fatal events, and a person is left with one thing - to die worthily; on the other hand, it is affirmed directly in the Soviet way, only with another, opposite, the satanic genius of Lenin is familiar. And as a consequence of this approach, a miracle plays a big, and maybe a decisive role in the work, which helps Ulyanov and does not help Kolchak.

An avalanche, a miracle - these and similar images cloud the image of time and various forces that determined the course of events. In understanding revolutions and civil war, the writer is most often in captivity of "left" stereotypes, which manifests itself in different ways. For example, in such thoughts of Kolchak: “It seemed, in what a supernatural way, former ensigns, apprentices of pharmacists from the Pale of Settlement, rural veterinarians<...>win battles and battles against the famous military generals trained in academies and in war? " However, it is known that 43% of the officers of the tsarist army and 46% of the officers of the General Staff fought on the side of the "Reds".

Of course, Kolchak could not know everything, but he certainly had an idea of the general trend. Ignorance of the true state of affairs, most likely, is the ignorance of the author. And if we assume the almost impossible, that this is really the admiral's thought, then such ignorance "does not play" on the image that the writer seeks to create.

There is a great temptation to believe Maksimov and the fact that Kolchak was a man far from politics, literally by chance, since November 1918, he turned out to be the Supreme Ruler of Russia. However, it seems that it is no coincidence that the writer rather vaguely, casually depicts the foreign period of Kolchak's life, for this period destroys the myth of the admiral's apoliticality. From June 1917 to November 1918, Kolchak negotiated with the ministers of the United States and England, met with President Wilson and, by his own admission, was almost a hired soldier. By order of British intelligence, he ended up on the Sino-Russian border, and later in Omsk, where he was proclaimed the Supreme Ruler of Russia.

It is likely that V. Maksimov and Kolchak are related not only by loneliness (the testimony of the writer himself), but also by a common fate. They both, I have no doubt, for noble motives, became dependent on those forces that made one the Supreme Ruler, the other the editor of the "Continent". Apparently, this is why Vladimir Yemelyanovich did not have the courage to peer into the abyss to the end.

Among the versions of what is happening, expressed by various characters in the novel, one more stands out, broadcast most often by Kolchak and Bergeron. The latter three times throughout the entire narrative speaks of the existence of an invisible force behind the backs of individual politicians, governments, a force orchestrating many events. However, the French officer, according to him, is afraid of the abyss that will open with such a vision of what is happening, he is afraid to name this force.

It is significant that Kolchak, who made a similar diagnosis (both "red" and "white" - cannon fodder, pawns in someone else's game), as well as

Bergeron avoids the answer with the following explanation: “I don’t want you to know about this, Anna, you still have to live and live, and you cannot hold out with this!” That is, the hero, walking at the edge of the abyss, in the end was afraid to look into it.

So, I’ll make an agreement for the heroes of the novel and its author, I’ll say what Maksimov undoubtedly knew. This, according to Bergeron's exact definition, the invisible web, this secret power, of course, is Freemasonry. Its double member (French and Russian lodges), the notorious Zinovy Peshkov, was the permanent representative of the Entente forces at Kolchak's headquarters.

In connection with this and other facts testifying to a conspiracy of different forces, to the regulation of many events during the period of the revolution and civil war, the concept of the writer, which was embodied in thoughts like the following: "The monarchy collapsed under the weight of its own weakness," and in the accusations against Nicholas II that were repeatedly expressed in the novel, clearly from the author's submission. I will cite the words of only three heroes: General Horvath, an unnamed old man, Kolchak: “I am his Imperial Majesty's servant, faithful and eternal, but, I will take a sin on my soul, I will say: his fault!”; “Where have you seen them innocent ... Our Tsar, lord, is the most guilty one”; “When it took an effort of will from him to take on the ultimate responsibility for the fate of the dynasty and the state, he chose cowardly to flee to this world, leaving the country at the mercy of unbridled devilry. And then: an inglorious renunciation, vegetation in Tobolsk, an early absurd death. "

This idea, persistently pedaled by V. Maksimov, is, to put it mildly, unconvincing both in the main and in particular (it remains only to add to Kolchak's words about the absurd death a statement from the "Evil Notes" of the Soviet "admiral" N. Bukharin about the princesses shot a little, and we get " white-red "humanistic-cannibalistic brotherhood). It also does not fit with the concept of historical fatalism, which largely determines, as already mentioned, the writer's vision of events.

However, the author of the novel is undoubtedly right in the fact that the abyss is hidden in the person himself, especially in the godless person, especially, I will add from myself, in a situation when this person is put forward as an ideal by explicit or hidden, equally godless forces. And it is not so much the Kolchaks and Timirevs who are opposed to the abyss, but the Yegorychevs and Udaltsovs, the spokesmen of traditional Orthodox values in the novel To Look Into the Abyss.

So, there is every reason to consider this work of the writer as his creative failure. I understand why in the early 90s Art. Kunyaev refused to publish the novel in Our Contemporary.

Among the best works of V. Maksimov is "Farewell from Nowhere". And in this novel, the image of the abyss, one of the most beloved by the writer, carries a multi-semantic load.

The abyss is a terrible, meaningless, hopeless big world, where the protagonist Vlad Samsonov is "a tiny ball, a mixture of water and clay, iron and blood, memory and oblivion."

The abyss is a social world, social darkness, which since childhood penetrates Samsonov, crumbles, deforms his soul and worldview, making it much more difficult to understand God's providence.

The abyss is the person himself, his many passions, first of all, “the high passion to reach the bottom of things”, “the passion of hasty love”, alcoholic passion, etc.

The abyss is also a painfully bewitching, ideologically unprincipled, honestly corrupt, falsely cannibalistic world of Soviet literature. And it is no coincidence that the first step of the boy Vlad in this world was the following lines, born under the influence of the newspaper and social abyss: “Enemy, we dare not harm! You will receive death for this! ”,“ Let it be known to the whole world ... // we will attract enemies to account. // We will sweep away the traitors with well-aimed fire from our face. // Lead Rain Will Fall // Our Beloved Leader On Them.

But the abyss is at the same time the path to the light, to God; it is, after all, a cross that a person should bear with gratitude.

This Orthodox understanding of man and time by V. Maksimov fundamentally distinguishes him from V. Grossman, A. Rybakov, Vaksenov, V. Voinovich, GM Markov and many other Russian-speaking authors. Vlad Samsonov had to come to such a vision, having overcome a long and difficult path.

For a long time in the soul and worldview of Vlad there is a struggle with varying success, about which the writer, in relation to many characters, says: “So we lived in the closed world of this strange oblivion, where in one person the victim and the executioner, the prisoner and the warden, the accuser and the accused were combined , unable to escape beyond its limits ... ".

The heroes who caused Samsonov's healing can easily be named by name: grandfather Savely, father, Seryoga, Agnyusha Kuznetsova, Abram Ruvimovich, Dasha and Mukhamed, Rotman, Vasily and Nastya, Boris Esman, Yuri Dombrovsky, father Dmitry, Ivan Nikonov, etc. These characters, fundamentally different from the heroes of "confessional" prose (which, popular during the formative years of Maksimov the writer, appears in the novel both as a background and as a model offered to Vlad. V. Maksimov negatively - softly and sharply - characterizes this is a phenomenon of Russian-language literature), are far from ideal, but their personality is determined by kindness and the "Divine gift of Conscience." And it is no coincidence that Samsonov, who lives in the epicenter of Soviet literature, for a long time does not see: the treasure is underfoot, it is these people who should become the true heroes of his books.

For understanding a person and time, the writer - a crooked mirror and a magnifying glass - is perhaps the most interesting character. Vlad on the creative path was waiting for many dangers, abysses. In the novel, the thought is expressed more than once: literature in itself is already an abyss, a disease, a drug, and the Soviet-Russian-speaking, I will add from myself, is a double abyss, many die in it, and among the survivors and living, according to V. Maksimov, graphomaniacs prevail , variously paid ideological and other marauders, whose "creations" are waste rock, the dust of art.

Through the author's characteristics, the speech of characters: Vlad, Esman, Dombrovsky and others - the writer derogatoryly and destructively characterizes Soviet literature (an autonomous body that exists parallel to reality) and its representatives, possessing a caste-egocentric consciousness, spinning in a whirlpool of “fantastic masquerade "Where everyone deceives himself and others.

However, individual "portraits" of writers, critics, scientists, artists, politicians (A. Sakharov, for example), "portraits" of Russian-speaking and Russian authors, political and religious figures raise many fundamental objections (it does not matter, the "portrayed" is named after himself or it is very clearly, in the words of A. Solzhenitsyn, "hinted"). Here are just a few names: Yu. Kazakov, V. Kozhinov, father Dmitry Dudko, ASakharov. When characterizing them, V. Maksimov negatively, as with the first three, or positively, as with ASakharov, is biased: factually inaccurate, evaluatively or conceptually superficial, or wrong.

Initially - in Siberia, Krasnoyarsk, Cherkessk - Samsonov tries to follow the familiar literary track, accepting the existing rules of the game. However, his “I” from time to time at different levels opposes and violates these rules, as evidenced by frank “conversations” with a responsible party worker in Krasnodar and the national classic Kh.Kh. in Cherkessk, an epiphany in a dirty room with sleeping guys, a sharp assessment of one's own creativity, etc.