Traditions and life of a peasant family. The significance of the peasant tradition in the formation of the culture of a noble estate Russian peasant culture

Russian dwelling is not a separate house, but a fenced yard in which several buildings, both residential and utility ones, were built. Izba was the general name for a residential building. The word "hut" comes from the ancient "isba", "source". Initially, this was the name of the main heated residential part of the house with a stove.

As a rule, the dwellings of rich and poor peasants in the villages practically differed in the quality and number of buildings, the quality of decoration, but they consisted of the same elements. The presence of such outbuildings as a barn, a barn, a barn, a bathhouse, a cellar, a stable, an exit, a bryozoan, etc., depended on the level of development of the economy. All buildings in the literal sense of the word were cut with an ax from the beginning to the end of construction, although longitudinal and transverse saws were known and used. The concept of "peasant yard" included not only buildings, but also the plot of land on which they were located, including a vegetable garden, a garden, a threshing floor, etc.

The main building material was wood. The number of forests with a wonderful "business" forest far exceeded what is now preserved in the vicinity of Saitovka. Pine and spruce were considered the best types of wood for buildings, but pine was always preferred. Oak was prized for the strength of the wood, but it was heavy and difficult to work with. It was used only in the lower rims of log cabins, for arranging cellars or in structures where special strength was needed (mills, wells, salt barns). Other tree species, especially deciduous (birch, alder, aspen), were used in the construction, as a rule, of outbuildings

For each need, trees were selected according to special characteristics. So, for the walls of the log house, they tried to pick up special "warm" trees overgrown with moss, straight, but not necessarily straight-grained. At the same time, not just straight, but straight-grained trees were necessarily chosen for a tessellation on the roof. Most often, log cabins were collected already in the yard or near the yard. We also carefully chose the place for the future home.

For the construction of even the largest log-type buildings, a special foundation was usually not erected along the perimeter of the walls, but supports were laid in the corners of the huts - large boulders or so-called "chairs" made of oak stumps. In rare cases, if the length of the walls was much more than usual, the supports were also placed in the middle of such walls. The very nature of the log structure of the buildings made it possible to restrict the support to four main points, since the log structure was an integral structure.

At the heart of the overwhelming majority of buildings lay "cage", "crown" - a bunch of four logs, the ends of which were chopped into a tie. The methods of such felling could be different in terms of execution technique.

The main constructive types of chopped peasant residential buildings were "cross-section", "five-wall", a house with a cut. For insulation between the crowns of the logs, moss was laid interspersed with tow.

but the purpose of the connection was always the same - to fasten the logs together in a square with strong knots without any additional connection elements (staples, nails, wooden pins or knitting needles, etc.). Each log had a strictly defined place in the structure. Having cut down the first crown, the second was cut on it, the third on the second, etc., until the frame reached a predetermined height.

The roofs of the huts were mostly covered with straw, which, especially in lean years, often served as fodder for livestock. Sometimes more prosperous peasants erected roofs made of boards or shingles. The tes was made by hand. To do this, two workers used tall trestles and a long rip saw.

Everywhere, like all Russians, the peasants of Saitovka, according to a widespread custom, when laying a house, put money under the lower crown in all corners, and a larger coin was supposed to be in the red corner. And where the stove was placed, they did not put anything, since this corner, according to folk ideas, was intended for a brownie.

In the upper part of the log house, across the hut, there was a uterus - a four-sided wooden beam serving as a support for the ceiling. The uterus was cut into the upper rims of the frame and was often used to hang objects from the ceiling. So, a ring was nailed to it, through which an ochep (flexible pole) of the cradle (shackle) passed. A lantern with a candle was hung in the middle to illuminate the hut, and later a kerosene lamp with a shade.

In the rituals associated with the completion of the construction of the house, there was a compulsory treat called "matichnoe". In addition, the laying of the uterus itself, after which there was still a fairly large amount of construction work, was considered a special stage in the construction of the house and was furnished with its own rituals.

In a wedding ceremony for a successful matchmaking, matchmakers never went into the house for the mother without a special invitation from the owners of the house. In popular language, the expression "to sit under the womb" meant "to be a matchmaker." The uterus was associated with the idea of the father's house, luck, happiness. So, leaving home, it was necessary to hold onto the uterus.

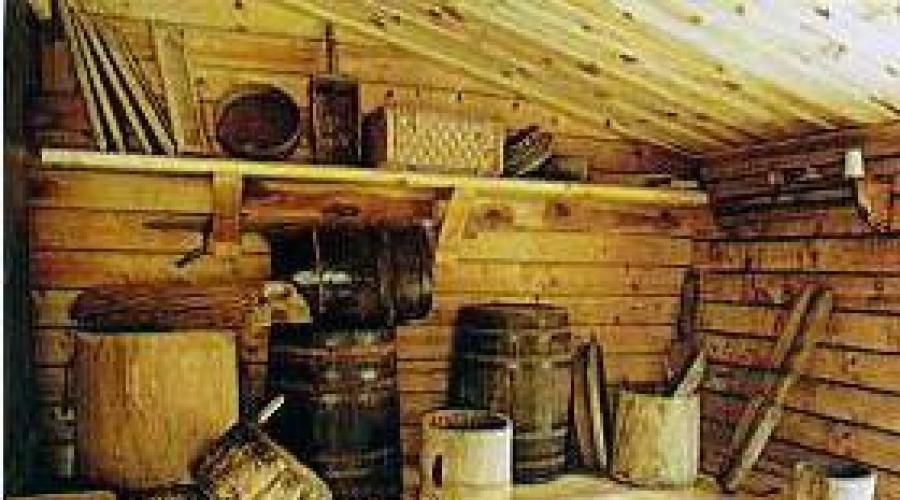

For insulation along the entire perimeter, the lower crowns of the hut were covered with earth, forming a mound, in front of which a bench was installed. In the summer, the old men whiled away the evening time on the bench and the embankment. Fallen leaves with dry soil were usually laid on top of the ceiling. The space between the ceiling and the roof - the attic in Saitovka was also called a stavka. It was usually used to store old things, utensils, dishes, furniture, brooms, bunches of grass, etc. Children, on the other hand, arranged their simple hiding places on it.

A porch and a canopy were necessarily attached to the residential hut - a small room that protected the hut from the cold. The role of the canopy was varied. This is a protective vestibule in front of the entrance, and additional living quarters in the summer, and a utility room where part of the food supplies were kept.

The soul of the whole house was the stove. It should be noted that the so-called "Russian", or more correctly the oven, is a purely local invention and is rather ancient. It traces its history back to the Trypillian dwellings. But in the design of the oven itself during the second millennium of our era, very significant changes took place, which made it possible to use fuel much more fully.

Building a good oven is not easy. At first, a small wooden blockhouse (opechek) was installed right on the ground, which served as the foundation of the furnace. Small logs split in half were laid on it and the bottom of the oven was laid on them - under, even, without a slope, otherwise the baked bread would turn out to be crooked. Above the hearth of stone and clay, a furnace vault was erected. The side of the oven had several shallow holes, called stoves, in which mittens, mittens, socks, etc. were dried. In the old days, huts (for chickens) were heated in black - the stove did not have a pipe. The smoke was leaving through a small drag window. Although the walls and ceiling became smoky, this had to be tolerated: a stove without a chimney was cheaper to build and required less firewood. Subsequently, in accordance with the rules of rural improvement, mandatory for state peasants, chimneys began to be removed over the huts.

The first to get up was the "big lady" - the owner's wife, if she was not yet old, or one of the daughters-in-law. She flooded the stove, opened the door and the smoker wide open. The smoke and cold lifted everyone up. The little guys were put on a pole to bask. Acrid smoke filled the entire hut, crawled upward, and hung from the ceiling taller than a human being. An ancient Russian proverb, known since the XIII century, says: "Smoky sorrows could not stand, they did not see warmth." Smoked logs of houses were less exposed to rotting, so the chick huts were more durable.

The stove occupied almost a quarter of the dwelling area. It was heated for several hours, but when heated, it kept warm and heated the room during the day. The stove served not only for heating and cooking, but also as a stove bench. They baked bread and pies in the oven, cooked porridge, cabbage soup, stewed meat and vegetables. In addition, mushrooms, berries, grain, and malt were also dried in it. Often they steamed in the oven, which replaced the bath.

In all cases of life, the stove came to the aid of the peasant. And the stove had to be heated not only in winter, but throughout the year. Even in summer, the oven had to be well heated at least once a week in order to bake a sufficient supply of bread. Using the property of the oven to accumulate, accumulate heat, the peasants cooked food once a day, in the morning, left the cooked inside the ovens until lunchtime - and the food remained hot. Only in the summer late supper did the food have to be warmed up. This feature of the oven had a decisive influence on Russian culinary, in which the processes of languor, boiling, stewing predominate, and not only the peasant one, since the way of life of many small landowners did not differ much from the peasant life.

The stove served as a lair for the whole family. On the stove, the warmest place of the hut, old people slept, who climbed there by steps - a device in the form of 2-3 steps. One of the obligatory elements of the interior was a floor - a wooden flooring from the side wall of the stove to the opposite side of the hut. Sleeping on the beds, climbing from the stove, dried flax, hemp, torch. For the day, they threw bedding and unnecessary clothes there. The floors were made high, at the height of the stove. The free edge of the boulders was often fenced off with low balusters so that nothing would fall from the boulders. Polati was a favorite place for children: both as a place to sleep and as the most convenient observation point during peasant holidays and weddings.

The location of the stove determined the layout of the entire living room. Usually the stove was placed in the corner to the right or left of the front door. The corner opposite the mouth of the furnace was the hostess's workplace. Everything here was adapted for cooking. There was a poker, a grapple, a pomelo, and a wooden shovel at the stove. Nearby there is a mortar with pestle, hand millstones and a kettle for leavening the dough. With a poker, they raked the ash out of the oven. With a grip, the cook clings to pot-bellied clay or cast-iron pots (cast irons), and sends them into the heat. In a mortar, she pounded the grain, peeling it off, and with the help of a mill she ground it into flour. A pomelo and a shovel were necessary for baking bread: with a broom, a peasant woman swept under the oven, and with a shovel she planted a future loaf on it.

There was always a scraper hanging next to the stove, i.e. towel and washstand. Under it was a wooden tub for dirty water. In the stove corner there was also a ship's bench (ship) or a counter with shelves inside, which was used as a kitchen table. On the walls were observers - cupboards, shelves for simple tableware: pots, ladles, cups, bowls, spoons. The owner of the house made them from wood. In the kitchen, one could often see earthenware in "clothes" made of birch bark - thrifty owners did not throw out cracked pots, pots, bowls, but braided them for strength with strips of birch bark. Above, there was a stove bar (pole), on which kitchen utensils were placed and various household utensils were laid. The eldest woman in the house was the sovereign mistress of the stove corner.

The stove corner was considered a dirty place, unlike the rest of the clean space of the hut. Therefore, the peasants always tried to separate it from the rest of the room with a curtain made of variegated chintz or colored homespun fabric, a tall wardrobe or a wooden bulkhead. The corner of the stove, thus closed, formed a small room called the "closet". The stove corner was considered an exclusively female space in the hut. During the holiday, when many guests gathered in the house, a second table for women was set up near the stove, where they feasted separately from the men sitting at the table in the red corner. Even men of their own family could not enter the female half without special need. The appearance of a stranger there was generally considered unacceptable.

The stove corner was considered a dirty place, unlike the rest of the clean space of the hut. Therefore, the peasants always tried to separate it from the rest of the room with a curtain made of variegated chintz or colored homespun fabric, a tall wardrobe or a wooden bulkhead. The corner of the stove, thus closed, formed a small room called the "closet". The stove corner was considered an exclusively female space in the hut. During the holiday, when many guests gathered in the house, a second table for women was set up near the stove, where they feasted separately from the men sitting at the table in the red corner. Even men of their own family could not enter the female half without special need. The appearance of a stranger there was generally considered unacceptable.

During the matchmaking, the future bride had to be in the stove corner all the time, being able to hear the whole conversation. From the corner of the stove she came out smartly dressed during the show - the ceremony of introducing the groom and his parents to the bride. There, the bride was expecting the groom on the day of departure down the aisle. In ancient wedding songs, the stove corner was interpreted as a place associated with the father's house, family, happiness. The bride's exit from the stove corner to the red corner was perceived as leaving the house, saying goodbye to him.

At the same time, the corner of the stove, from where there is an exit into the underground, at the mythological level was perceived as a place where people can meet with representatives of the "other" world. Through the chimney, according to legend, a fiery devil snake can fly to the widow yearning for her dead husband. It was believed that on especially solemn days for the family: during the baptism of children, birthdays, weddings - the dead parents - "ancestors" come to the stove to take part in an important event in the life of their descendants.

The place of honor in the hut - the red corner - was located obliquely from the stove between the side and front walls. It, like the stove, is an important landmark of the interior space of the hut, well lit, since both of its walls had windows. The main decoration of the red corner was a shrine with icons, in front of which a lamp was burning, suspended from the ceiling, therefore it was also called a "saint".

They tried to keep the red corner clean and elegantly decorated. He was removed with embroidered towels, popular prints, postcards. With the advent of wallpaper, the red corner was often pasted over or isolated from the rest of the hut space. The most beautiful household utensils were placed on the shelves near the red corner, the most valuable papers and objects were kept.

They tried to keep the red corner clean and elegantly decorated. He was removed with embroidered towels, popular prints, postcards. With the advent of wallpaper, the red corner was often pasted over or isolated from the rest of the hut space. The most beautiful household utensils were placed on the shelves near the red corner, the most valuable papers and objects were kept.

All significant events in family life were noted in the red corner. Here, as the main piece of furniture, there was a table on massive legs, on which runners were installed. The runners made it easy to move the table around the hut. It was placed in front of the oven when bread was baked, and it was moved when the floor and walls were washed.

It was followed by both everyday meals and festive feasts. Every day at lunchtime the whole peasant family gathered at the table. The table was large enough for everyone to have room. In the wedding ceremony, the matchmaking of the bride, her ransom from her bridesmaids and her brother were performed in the red corner; from the red corner of her father’s house they took her to a church wedding, brought her to the groom’s house and also led her to the red corner. During the harvest, the first and last compressed sheaf was solemnly carried from the field and set in the red corner.

"The first compressed sheaf was called the birthday man. The autumn threshing began with him, the sick cattle were fed with straw, the grains of the first sheaf were considered healing for people and birds. The first sheaf was usually healed by the eldest woman in the family. It was decorated with flowers, carried to the house with songs and put on in the red corner under the icons. " The preservation of the first and last ears of the harvest, endowed, according to popular beliefs, with magical powers promised prosperity to the family, home, and the entire economy.

Everyone who entered the hut first took off his hat, crossed himself and bowed to the icons in the red corner, saying: "Peace be to this house." Peasant etiquette ordered a guest who entered the hut to stay in half of the hut at the door, without going behind the womb. An unauthorized, uninvited intrusion into the "red half" where the table was placed was considered extremely indecent and could be perceived as an insult. A person who came to the hut could go there only at the special invitation of the owners. The most dear guests were seated in the red corner, and during the wedding - the youngest. On ordinary days, the head of the family sat here at the dinner table.

The last of the remaining corners of the hut, to the left or to the right of the door, was the workplace of the owner of the house. There was a bench where he slept. A tool was kept under it in a drawer. In his free time, the peasant in his corner was engaged in various crafts and minor repairs: weaved sandals, baskets and ropes, cut spoons, hollowed out cups, etc.

Although most peasant huts consisted of only one room, not divided by partitions, an unspoken tradition prescribed the observance of certain placement rules for members of the peasant hut. If the stove corner was the female half, then in one of the corners of the house there was a special place for the older married couple to sleep. This place was considered honorable.

Shop

Most of the "furniture" was part of the structure of the hut and was motionless. Along all the walls, which were not occupied by the stove, there were wide benches, hewn from the largest trees. They were intended not so much for sitting as for sleeping. The benches were firmly attached to the wall. Other important pieces of furniture were benches and stools, which could be freely carried from place to place when guests arrived. Above the benches, along all the walls, shelves were arranged - "half-shelves", on which household items, small tools, etc. were stored. Special wooden pegs for clothes were also driven into the wall.

An integral attribute of almost every Saitovka hut was a pole - a bar embedded in the opposite walls of the hut under the ceiling, which in the middle, opposite the pier, was propped up by two plows. The second pole rested with one end against the first pole, and with the other against the pier. In winter, this design was the support of the mill for weaving matting and other ancillary operations associated with this fishery.

Spinning wheel

The hostesses were especially proud of the chiseled, carved and painted spinning wheels, which were usually placed in a prominent place: they served not only as an instrument of labor, but also as a decoration for the home. Usually, with elegant spinning wheels, peasant girls went to "get-togethers" - cheerful rural gatherings. The "white" hut was cleaned with household weaving items. The beds and the couch were covered with colored linen curtains. On the windows there were curtains made of homespun muslin, the window sills were decorated with geraniums, dear to the peasant's heart. The hut was especially carefully cleaned for the holidays: the women washed it with sand and scraped it white with large knives - "mowers" - the ceiling, walls, benches, shelves, and shelves.

The peasants kept their clothes in chests. The more wealth there is in the family, the more chests there are in the hut. They were made of wood, upholstered with iron strips for strength. Chests often had clever mortise locks. If a girl grew up in a peasant family, then from an early age a dowry was collected for her in a separate chest.

A poor Russian man lived in this space. Often in the winter cold, domestic animals were kept in the hut: calves, lambs, kids, piglets, and sometimes poultry.

The artistic taste and skill of the Russian peasant was reflected in the decoration of the hut. The silhouette of the hut was crowned with carved

the ridge (oohlupen) and the roof of the porch; the pediment was decorated with carved moorings and towels, the planes of the walls - window frames, often reflecting the influence of the city's architecture (baroque, classicism, etc.). The ceiling, door, walls, stove, less often the outer pediment were painted.

Non-residential peasant buildings constituted the household yard. Often they were gathered together and placed under the same roof as the hut. A household yard was built in two tiers: in the lower one there were cattle sheds, a stable, and in the upper one there was a huge sennik filled with fragrant hay. A significant part of the household yard was occupied by a shed for storing working equipment - plows, harrows, as well as carts and sleds. The more prosperous the peasant, the larger his farm was.

Non-residential peasant buildings constituted the household yard. Often they were gathered together and placed under the same roof as the hut. A household yard was built in two tiers: in the lower one there were cattle sheds, a stable, and in the upper one there was a huge sennik filled with fragrant hay. A significant part of the household yard was occupied by a shed for storing working equipment - plows, harrows, as well as carts and sleds. The more prosperous the peasant, the larger his farm was.

A bathhouse, a well, and a barn were usually placed separately from the house. It is unlikely that the then baths were very different from those that can still be found today - a small log house,

sometimes without a dressing room. In one corner there is a stove, next to it are shelves or shelves, on which they steamed. In another corner there is a barrel for water, which was heated by throwing hot stones into it. Later, cast iron boilers were installed to heat water in the heater. To soften the water, wood ash was added to the barrel, thus preparing the lye. The entire decoration of the bathhouse was illuminated by a small window, the light from which drowned in the blackness of the smoky walls and ceilings, since in order to save firewood, the baths were heated "in black" and the smoke came out through the slightly open door. From above, such a structure often had an almost flat pitched roof covered with straw, birch bark and sod.

The barn, and often the cellar under it, was placed in full view against the windows and at a distance from the dwelling, so that in the event of a fire in the hut, to preserve the annual supply of grain. A lock was hung on the door of the barn - perhaps the only one in the entire household. The main wealth of the farmer was kept in the barn in huge boxes (bottom bins): rye, wheat, oats, barley. No wonder in the village they used to say: "What is in the barn, so is in the pocket."

QR code of the page

Do you like reading from your phone or tablet more? Then scan this QR code directly from your computer monitor and read the article. To do this, any "QR Code Scanner" application must be installed on your mobile device.

noble estate, peasant traditions, harmony with nature, mythologeme of reason

Annotation:The article discusses the principles of the estate organization, which are not based on a diametric opposition of the values of urban and rural life. Here, urban civilization, with the dominant mythologeme of the human mind, is opposed to the natural beginning of rural life, the idea of harmony with nature.

Article text:

An important factor for understanding the status of a noble estate in an agrarian society was two areas of its functional purpose: preserving traditions and ensuring development. The estate, both in material and physical terms (as a cultural space), and in the minds of its inhabitants (with a change in external forms of existence and chronotopic characteristics) was in a borderline position between town and country. “... This "ambivalence" of the estate, its connection with both poles of social life gave it the meaning of a kind of universal symbol of Russian life, deeply rooted in its history ... "

The principles of the manor organization are not based on a diametric opposition of the values of urban and rural life. But the urban civilization, with the dominant mythologeme of the human mind, is opposed to the natural beginning of rural life, the idea of harmony with nature. For a nobleman who grew up on a manor, city life was not an ideal of life. Even if he wanted to, he could not get rid of the image of a happy childhood, to some extent, idealizing the way of life in the estate. This explains the duality of the noble cultural tradition - the forced living in the city and the voluntary choice of village life later, which was perceived by the nobleman as gaining freedom:

“... In the person of a Russian nobleman, culture takes on the conscious position of a civilized person: to return to the bosom of nature, gaining independence, feeling individual forces in oneself, to combine them with the forces of nature for the good of society ... Rational and natural principles are united here, saturated with historical symbolism. Positive - the elegance of architecture and the internal comfort of housing, the possibility of cultural communication with a close-minded circle of friends, the simplicity of the internal organization and the integrity of household and family life, closeness to nature and immediacy of human relations ... "

The nobility, as the main bearer of the manor mythologeme and the representative of the more progressive part of society, strove to create a universal space, which is a close interconnection of economic, social and cultural factors. Returning to the estate obliged the nobleman, brought up in the military or civil service, to show pragmatism and prudence in social and economic activities, the intensity of intellectual and intuitive activity. The system of his knowledge about the cosmological concepts of the peasant tradition was abstract and imperfect, the accumulated experience was not enough for radical transformations. At the same time, estate life in the province imposes certain obligations on the owner's personality in private life, forming new models of his behavior in society. The norms generally accepted in the capital cities are completely unacceptable in the patriarchal society of the province. The organization of the estate space, the perception of oneself in this space, the management of the illiterate peasants subject to him demanded the abandonment of a number of customs and conventions adopted in the capital's aristocratic circles. It was necessary to learn to understand the world of nature, peasant psychology, to delve into the intricacies of the agricultural economy, while remaining a full-fledged member of the noble corporation. When applied to the estate style of life, the concept of "philosophy of the economy" is not a metaphor. The integrity of the nobleman's ideological foundations has a direct impact on the choice of priorities for behavior and forms of agricultural activity, in the process of which the nobleman turned to the peasant experience of running an economy accumulated over the centuries. The natural features of the area, the specifics of agricultural sectors, monitoring of cultivated and wild plants, domestic and wild animals, weather conditions, soil resources - a vast area of knowledge, skills and abilities that were the property of the peasant community, and they needed to be able to actively and effectively apply on practice. Constant ideological, mental correlation, interconnection of world and everyday space, thoroughness and unconditional adherence to Orthodox dogmas, characteristic of the peasant tradition, acquire a special status in the noble worldview, subordinating to itself the utilitarian, pragmatic concerns and values of everyday life.

For a traditional community, a noble estate should become a protective barrier against the aggressive actions of civilization, gradually involving it in economic and cultural development. The invasion of the peasant space, the expansion of a new culture into the material environment of the patriarchal village was an attack on the traditional foundations of the community, and the desire to establish innovative Western European standards by neutralizing ethnic and folklore forms was a cultural provocation. Therefore, maintaining the stability of relations between the estates required the owner of the estate to exert stress and concentration of will, moral and spiritual strength. And it obliged the nobleman to maintain a certain level of social consolidation, to respect the system of values, rules, customs, social standards of the peasant class. But the lack of options, in the conditions of the serf system, for the formation of parity social relations was expressed in the implementation of conditional goals that did not go beyond the framework of real social relations.

Under the conditions of an agrarian society, the new Western European culture did not have an active influence on the peasant tradition. Two worlds of culture - noble and peasant existed on their own. As Western European borrowings acquire an independent national position, a socio-cultural dialogue begins, and subsequently, modernization processes in the space of the provincial peasant society. The prerogative in this process belonged to the estate.

At the first stages of its formation, the estate, as a cultural space, has quite clear boundaries within the framework of an architectural and park complex, which at the same time had its continuation in the specific perspectives of nearby groves and fields. But gradually, as it spreads into the surrounding space, the boundaries of the estate are neutralized. "... For a man of the manor tradition, everything" participatory "he mastered became a fact of unconditional" spatial attraction ... "... The spiritual vertical of the noble culture, with access to the peasant space, acquires a horizontal dimension. Actively interacting with the territorial, economic, social space of the patriarchal village and, despite the complete absence of legal culture, the provincial estate acquires a special, different from the capital residences, specificity, individual configuration, architectonics, ways of broadcasting and exchanging spiritual, cultural and economic with the folk tradition. experience.

The constancy and periodic renewal of the basic parameters of the life of the peasant community became the source of a certain conservatism in its worldview and culture. The estate for patriarchal ontology, peasant psychology is an object of special perception . Traditional consciousness defines the opposition between the noble and peasant loci by the dual opposition of the sacred world of the estate and the everyday life of the surrounding space. The nature of this cultural opposition is rooted in the subconscious levels of the peasant's mental organization.

For the peasant community, the imaginative perception of the estate world is characterized by the focus of psychological, spatial, material and objective characteristics of life, which is characterized by the utmost civilizational density: architectural, cultural, spiritual, moral, economic. Rational orderliness, aesthetic and emotional loading of the estate space contribute to its idealization and sacralization in the archaic consciousness of the peasantry and are transferred from the estate mythical image to the image of the owner. At the same time, the model of the relationship between the owner and the peasants is built by analogy with the internal hierarchy of the peasant community. The appeal of a gray-haired old man to the young master, "father", is nothing more than a projection of relations existing within the family, reproducing the attitude of the head of the family to power, who, in the peasant's perception, was the owner of the estate.

Manor life was divided into three components - everyday, economic and spiritual. In the sphere of spiritual culture, the nobility and the peasantry had the same roots, traditions and customs. Within the economic activity of the estate, there is a certain economism - the material wealth of the owner depends on the productivity of the serfs. In everyday life and everyday life, it is difficult for a nobleman to do without a courtyard, whose services he constantly needs. The patriarchal traditions of the agrarian society assumed the landowner's moral responsibility for the fate of the peasants, both the right to govern them and the duty to take care of them, help them in need, and fairly resolve their disputes. The cult of the “father of the family”, the indisputability of authority and confidence in its unlimited possibilities, doubts about their independence and the habit of lack of freedom were so strong in the minds of the peasants that legal freedom after the abolition of serfdom was perceived ambiguously by the peasantry.

The direct presence of the owner in the estate, who in the psychological perception of the serf was a support, protection, and in some cases, a guarantee against the arbitrariness of managers, was a positive factor in the life of the rural community. Russian army officer and Smolensk nobleman Dmitry Yakushkin wrote: “... The peasants ... assured them that I would be so useful to them, that in my presence they would be less oppressed. I became convinced that there is a lot of truth in their words, and moved to live in the village ... "

The estate for all representatives of the family is the starting point of the active and creative perception of the world. Born on the estate, they served in capitals, receiving ranks and awards, wandered around the world in search of new impressions and ideals, and found their last refuge, as a rule, in the family necropolis of their native estate. The eternal love for the "native ashes", sometimes not even explainable, in this case - a feeling of a high philosophical order, which, leveling class differences, is an implication of the spiritual unity of the nobility and the common people. The color of the estate life was determined by the spiritual space, history, traditions, which were reverently guarded and passed on from generation to generation, with significant events captured forever in family heirlooms, with a family gallery, library, collections, family albums, tombstones near the church. The continuity of family traditions - “it is so accepted here”: adherence to patriarchal principles, respect for elders, living with a large family - determined the behavior model of the inhabitants of the estate. More than one generation of nobility, for whom nobility, duty, honor, responsibility were the most important qualities of every member of the nobility, were nurtured on generic values, on “legends of deep antiquity”. The formation of the personality principle in the estate took place within the framework of the natural environment, aesthetic environment, a limited circle of communication, initiation into work, supplemented by the study of literary, historical and scientific sources and the obligatory presence of role models, represented by older representatives of the family. These factors had a significant impact on the formation of the phenomenon of historical authorities, scientists and artists. The system of values of the nobility underwent a transformation over time, but the eternal ones remained - “for the Faith, the Tsar and the Fatherland”. Subsequently, the material sphere of the estate aesthetics directly affects the process of the formation of spiritual values and contributes to the process of mythologicalization of space in the minds of the inhabitants of the estate.

"... The myth turns out to be possible only with the balance of the terms, including the material ones, and the noble estate functions in the exemplary unity of its cultural traditions ..."

The combination of personal impressions and objective reality into a general picture of life enhanced the ability of the human soul to return to the past, contributed to its idealization and formation in the noble tradition home home phenomenon

- a space that reveals and stores the spiritual and material values of several generations of the clan. For examples, let us turn to the memoir and epistolary legacy of Boris Nikolaevich Chicherin and Yevgeny Abramovich Boratynsky. In a letter to Pyotr Andreevich Vyazemsky in the summer of 1830, Boratynsky wrote: “... You can live wherever you want and where fate wants, but you need to live at home…».

These words of the poet express the essence and are fundamental in the concept home home phenomenon, in which it is possible to highlight the following structural elements:

- home corner (dwelling house) - a safe space and a safe refuge;

- a piece of land (park area), which can be looked after and arranged in accordance with your wishes and ideas;

- a system of objects (manor temple, chapel, necropolis) - the material embodiment of spiritual values and collective ancestral memory;

- a group of people (parents, children, brothers, sisters, nannies, governesses, home teachers, courtyard people, peasant community) who have spiritual and family ties;

- the cultural content of the estate - family traditions, habits and occupations of the inhabitants, household furnishings, family comfort, a wide variety of cultural phenomena (objects of art, science, technology).

The emotional factors of perception of the native estate, the beauty of the surrounding nature, the close proximity of relatives, laid down from early childhood, are the starting point for the formation in the minds of the younger generation home cult , which throughout life serves as the basis on which the generic cultural universals of the nobility are based. At the same time, the manor space is the starting point of the creative perception of the world. All the achievements of the manor culture that contribute to the formation in the noble tradition of an intimate image of the native manor, which will become a fundamental factor in the process of formation home cult , were realistic and symbolic at the same time. The material objects of the estate - a dwelling house with a library and a family portrait gallery, a manor temple, a park zone - carried information about the history and genealogy of the clan, about philosophical and scientific truth; beauty was reflected in interior items - sculpture, paintings, literary works; divine - in objects of worship and religious symbolism; good is in the morals and being of the inhabitants. Patriarchal traditions, strong spiritual and family ties of the nobility contributed to the fact that home cult "Passed on by inheritance." Boratynsky, who considered Mara a holy place, subsequently building a house in Muranovo, will already prepare perception for his children home home phenomenon , on the example of which the primacy of the myth in relation to real practical activity is visible. The manor house, built in accordance with the needs and tastes of the owner, vividly reflected the style and sense of the time, which the poet himself called “eclectic”. Muranov's device was based on practical-rationalistic tendencies, combined with the identity of the family, household and economic structure, natural and artificial, which was the embodiment of the universality and harmony of the universe. In letters to close people, the poet's joy from finding a "family nest" is obvious:

« ... The new house in Muranovo is under a roof ... Something extremely attractive turned out: improvised little Lubichi ... Thank God, the house is nice, very warm ... The house is completely finished: two full floors, plastered walls, floors painted, covered with iron ... Our life has changed the fact that we rarely go to Moscow ... Now, thank God, we we spend more time at home …».

Existence in the family tradition of tradition is a phenomenon of a special order. In the Chicherin family, the legend was associated with the father of Boris Nikolaevich: having bought the estate, Nikolai Vasilyevich widely celebrated this event - with a large congress of guests in honor of the name day of his wife Ekaterina Borisovna (nee Khvoshchinskaya.). As a sign of respect for the world, he laid a table for the peasants and, welcoming them, promised to manage the estate diligently, without burdening the community with unnecessary burdens. With this civil act, Nikolai Vasilyevich conditionally realized the idea of class unity, which excited at that time the minds of the liberal-minded nobility. The paternal attitude towards their serfs was also distinguished by the next owner of the estate, who sacredly revered the family tradition, which could develop and be preserved only on the condition of long-term preservation of "family relations" between the owners of the estate and the peasants. The authority of parental authority was a spiritual law that determined and regulated the life of subsequent representatives of the family.

Cult home was so strong in the worldview of the nobility that even in the post-reform period, despite the changes in the economic status of the estate, the construction of family nests continued in the provinces. B.N. Chicherin in the 1880s took up the improvement of the Karaul estate. The absence of direct offspring (three children died at an early age) left a negative imprint on the psychological mood of the owner of the estate, but a sense of duty, the perception of the estate as a heritage of the family obliged him to complete the work started by his father:

«… I myself happily set about decorating the house, using my small savings to build my own nest ... Now some antique furniture, chandeliers, vases, porcelain, partly inherited by my wife (Alexandra Alekseevna, nee Kapnist), partly bought in St. Petersburg ... they bought or made the necessary additional furniture at home, ordered them from Paris for the occasion and bought various cretons in St. Petersburg, and Moscow calicoes for the bedrooms; our old home carpenter Akim made stands for vases and curtain rods for draperies based on my drawings. All this was a source of continuous pleasure for us. The wife settled down to her taste, and in every new improvement I saw the completion of my father's work, the decoration of an expensive nest, the continuation of family traditions ... "

The positive energy of Boris Nikolayevich, with which the manor interiors are arranged, accumulated in the space of a residential building, remained in various "visual" texts - pieces of furniture, paintings, small metal, marble and porcelain sculptures, contributing to the establishment of a dialogue with future generations. The nostalgic retrospective tones characteristic of the state of mind of Boris Nikolaevich somewhat idealize the estate way of life, but at the same time, by turning thoughts and feelings to the past, they felt the irreversible passage of time more sharply. This self-reflection and persistent self-awareness contributed to the acquisition of that elegiac tonality that determined the semantics of the estate architectural and park ensemble. The owner's attention, focused on the continuation of the family tradition, indicates the most important meaning of the estate model of being - the desire to bequeath to the descendants an established family estate.

Having deployed a prosperous farm in the estate, Boris Nikolaevich very actively delved into peasant affairs. In 1887, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the acquisition of the Guard, mass services, a solemn memorial service at the grave of his parents and a common feast, he will continue the family tradition of spiritual unity with the peasant community, which will determine his actions and deeds throughout the rest of his life.

“... Great interest and adornment of rural life are good relations with the surrounding population. I inherited them. When leaving the serf state, the old moral bond was not destroyed. The peasants of the guard knew me from childhood, and it gives me heartfelt pleasure not only to know everyone by sight and by name, but to be familiar with his moral qualities, with his position and his needs. Everyone turns to me in any adversity: one has a horse that has died, the other has no cow, and the children are asking for milk, and the third has fallen apart. With a small amount of money, you can help everyone, and you know and see that this help goes to work. The wife, for her part, entered into the closest relationship with them; she heals all of them, knows all the women and children, constantly walks around the huts. For many years we have been living like a family ... "

The economic well-being of the Guard for almost fifty years (the second half of the 19th century) is an exceptional phenomenon that could not take place without the personal participation of the owner, his consistent efforts to introduce advanced techniques of agricultural technology and agriculture.

The proximity of the estate to the peasant village contributed to the formation of certain representatives of the nobility of a sense of moral guilt. Worries about the unfairness of existing relations, the desire to comply with the humane norms of Orthodox morality, the presence of actions that meet the requirements of an enlightened owner - all this is difficult to link with the concepts of "class exploitation". The liberal views of the landowner in relation to the peasants contributed to the organization of a patriarchal society on the principle of a large family, the head of which was the owner of the estate. The patronage of peasant families by the owner of the estate was expressed in patronage, trusteeship, and management of peasant families. In the lean year 1833, in the fall, E.V. Boratynsky, realizing the responsibility for the peasant community of the estate, wrote from Mary to Ivan Vasilyevich Kireevsky:

“... I'm all mired in economic calculations. No wonder: we have complete hunger. For the food of the peasants we need to buy 2,000 quarters of rye. This, at current prices, is 40,000. Such circumstances can give rise to thought. I, as the eldest in the family, bear all the administrative measures ... "

A noble estate and a peasant village, existing within the boundaries of one estate, could not but touch each other. A provincial estate, as a socio-cultural object, is the result of the unity of the way of thinking of the owner, who acted as a social customer, and the creative process of the performers. When arranging the estate, all the achievements of world art - painting and architecture - are used in the decors of buildings and interior design. But at the same time, the internal potential of the estate is actively used - the abilities and talent of serfs, whose dependent position was not only a material base for the development of a noble culture, but also served as an inexhaustible source of human resources. Folk craftsmen and talents from the common people were the human material that would later become the color of Russian culture. In a feudal society, a talented peasant was a hostage to the system, unable to develop his talent. Raised in the mainstream of the noble culture, the serf intelligentsia in their worldview was much closer to the nobility than to the peasantry with its traditional way of life. The drama of the position of serf masters was also in the fact that according to their social status they were serfs, but according to the system of ideological values, occupation, and creative skills they no longer belonged to the peasant world. For all the paradox of the situation when a creative person was legally and economically dependent, the contribution of folk craftsmen to the process of shaping the culture of the noble estate culture was enormous. Individual representatives of the nobility were characterized by manifestations of paternalism in relation to especially talented peasants - the only opportunity for them to realize their talent in the conditions of the serf system. For example, Pavel Petrovich Svinin, a diplomat and publisher, according to the Russian tradition, on the bright holiday of Easter with the serf artist Tropinin, offered him his freedom in an Easter egg. Serf artists - the Argunov brothers, actors - Mikhail Shchepkin and Praskovya Kovaleva-Zhemchugova, architect Andrey Voronikhin have reached a high level of professional skill, developing their activities in line with the modern cultural process.

The development of relations between the landowner and the peasants was also determined by the preferences of the owner, the level of his cultural development and the economic situation of the peasants, they were separated by "huge distances" - social and property. In the life of a noblewoman and a peasant woman in a provincial estate, an analogy can be traced and traditional features are preserved - both are linked by family ties, the way of life and concerns about raising children. In the children's perception, the class difference practically did not exist. The children of the courtyards were the partners of the noble children in games and amusements. The upbringing and initial education of noble children in the estate often took place together with poor relatives and courtyard children, which left a certain imprint on the quality side of the upbringing of peasant children.

The idea of enlightening the people did not leave the minds of the progressive nobility, which, through the spread of literacy, introduction to art through the construction of serf theaters and the organization of folk choral groups, tried to distract the peasant from the tavern, to make him an active participant in cultural events taking place in the space of a provincial estate: "... I fell in love with the Russian peasant, although I am very far from seeing him as the ideal of perfection ...". But individual manifestations of negative character traits in the Russian peasant can in no way be considered a national archetype. The peasantry as a social corporation was distinguished by a high intracommunal organization with a historically, spiritually and culturally conditioned form of life that was not contained in its legal status. The ability to perceive the signs and phenomena of the surrounding world of nature, the wisdom accumulated by centuries of experience, prudence in interaction with great efficiency helped the Russian peasant to maneuver between the accidents of life, which, at first glance, can determine the national characteristics of the Great Russian. Confirmation of the high spiritual and moral qualities and hard work of the peasants is their service as housekeepers and maids in the homes of nobles and nurses of their children:

"... We had such a custom that when letting the nurse go home, at the end of the feeding period, the gentlemen, as a reward for the successful and conscientious end of this business, gave her daughter freedom, and if the newborn was a boy, then he was released from recruitment ..."

Until the end of their lives, peasant women who raised noble children were distinguished by disinterestedness, touching attitude and extreme affection for their pupils, and cases of respect on the part of masters and their children for courtyard people, who were practically members of a noble family, were not isolated. Strong intra-class moral and patriarchal traditions influenced the actions of the peasants at critical moments for one or another member of the community, for example, when the whole world ransomed a young peasant from a landowner, relieving him of the soldier's service.

Interest in the peasant as a human person was directly the basis for the revival of sources of non-classical heritage - monuments of Slavic culture and folklore sources. The interrelation of folk agricultural and cultural traditions, manifestations of national mentality, socio-historical and religious factors contributed to the cultural and everyday rapprochement of the two estates. Peasant customs and traditions entered the fabric of the noble culture, becoming its integral and integral part. Life in the estate was closely connected with the folk calendar, with folk traditions, rituals, amusements that were arranged at Christmas, Christmastide, Shrovetide. Easter was a special Orthodox holiday for all the inhabitants of the estate. In the estate Sofievka of the Saratov province, the estate of Sofia Grigorievna Volkonskaya (sister of the Decembrist Sergei Volkonsky) whose serf Ivan Kabeshtov in his memoirs could not: “… To deny yourself the pleasure of remembering the Volkonskys with a kind word. They have always been kind and even humane with their serfs. By their order, the peasants were obliged to work in the corvee no more than three days a week; Sunday and public holidays were definitely prohibited. Easter was celebrated for a whole week ... "

The change after the reform of 1861 of the economic basis of the provincial estate, the status of its owner and the legal status of the peasant, contributes to the fact that there is clearly a convergence of cultures in the estate space, which is expressed not only in the influence of folk culture on the nobility, but also in the influence of the noble culture on the folk. Elements of the culture of the nobility are actively penetrating the peasant environment. The appearance of village buildings is changing, handicraft items for utilitarian purposes are replaced with similar ones, but factory-made, clothes made from homespun cloth are becoming a thing of the past. The cultural space of the provincial estate retains its independence, the estate becomes the keeper and conservator of the noble traditions, but the culture of the “noble nest” is unified, becoming more democratic and liberal. The social essence of the estate is being transformed, its significance in the life of the nobility and the peasant community is changing, its content and economic functions are changing, but the spiritual and moral value as a family nest remains unchanged. This period, contrary to popular belief, cannot be called a time of decline in the production, material and spiritual culture of the estate:

“... The first years after the liberation of the peasants were very favorable for our province ... The harvests were good; the peasants had excellent earnings; the landlords not only did not complain, but, on the contrary, were completely satisfied. I have not seen any impoverishment either in our district or in others. There were, as always, people who went broke through their own fault; their estates passed into the hands of those who had money, that is, merchants. But this was an exception. Abandoned estates and abandoned farms have never met us ... "

The integrity of the manor culture phenomenon is not limited to only a positive analysis. Like any socio-economic structure, the estate had its negative aspects of life. The relative freedom that the nobles received in a provincial estate turned into a powerful instrument of domination, expressed in the arbitrariness of the landowner; the need to sell or pledge the estate, recruitment, the transformation of the estate into a theater of military operations (the Patriotic War of 1812) are the negative aspects of the estate phenomenon, which must be considered in the context of historical and economic processes. The relationship between the landowner and the peasant in the provincial estate, formed under the conditions of the serfdom, gave the owner the opportunity to control the fate of the people entrusted to him - punishment, sale, loss at cards were not exceptional cases. The serf peasant of the Kaluga province Avdotya Khrushchova, according to her recollections, at the age of 10 was played by the master at cards to the landowner of the Yaroslavl province of the Lyubimovsky district Shestakov Gavril Danilovich, who “ ... often punished servants, most severely persecuted disrespect for the landlord's power. But he did not allow his children to punish the servants, saying: "Make your own people and when you dispose of them, and do not dare to touch your parent!" He did not ruin his peasants, he took care of them in his own way, observing his own interests ... "

The attitude of the landowner to the peasant was regulated by the legislatively enshrined power of the owner, but private property, to which the peasants belonged, was the economic basis of the state structure. The maintenance of property belonging to a nobleman in due order was controlled by the state, interested in peasant well-being for the successful functioning of tax and tax policy. These circumstances imposed certain obligations on the owners of estates, who were forced to delve into the economic and family life of their peasants. For example, Platon Aleksandrovich Chikhachev, the founder of the Russian Geographical Society, in his estates Gusevka and Annovka of the Saratov province in his free time could talk with serfs for hours, had complete information about every peasant household and always tried to satisfy peasants' requests for help. But strict, sometimes turning into cruel, measures against the peasants were applied to them if anyone dared to beg.

The use of child labor is also considered the negative side of the landlord economy. But, at the same time, labor is a good educational tool, provided that the children worked in the field only in the summer season. And the downtroddenness of the peasantry, when children were deliberately not sent to school, did not contribute to the formation of positive moral and ethical traits in the character of the younger generation of peasants: “ ... the small population of the Guard, employed in tobacco production from an early age, is accustomed to work. This industry gives me excellent income, and the peasants receive up to two thousand rubles a year on it, mainly through the work of children. In a hungry year, they told me that in the past, parents fed their children, and now children are feeding their parents ... "

Considering the relations between the two estates in the mainstream of social development, we can give examples of the biased attitude of the peasant to the nobleman and the commission of rash acts that were the result of previous negative conditions. Brought up on Christian traditions, the Russian peasant was distinguished by kindness, humility and religiosity. But at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, in the period of the search for new forms of life, the reassessment of values and nihilism, some representatives of the peasantry are characterized by a perversion of the positive features of a past life, maximalism and extremism. The previously mentioned pogroms by peasants of noble estates in the fall of 1905 testify to the presence of negligible interest in material culture and the ability to suddenly change feelings and interests - the destruction of beauty created by oneself. The phenomenon of manor culture, which in the presence of some negative features does not become less significant, retains its impact on the spiritual world of the inhabitants - mind, feelings, thinking, contributing to the awareness, understanding and acceptance of cultural and aesthetic values, as a result of which culture turns into a social quality of each inhabitant estates.

.To civilized people, many of the rituals of Russian peasants may seem like episodes from horror films. However, our ancestors did not see anything terrible in such rituals. Voluntary self-immolation or human sacrifice, under certain circumstances, even seemed logical to them: such were the customs.

For a husband to the next world

In the old days, the death of her husband foreshadowed the Russian peasant woman and her own demise. The fact is that in some regions the ritual of burning the wife along with her deceased husband was adopted. Moreover, women went to the fire absolutely voluntarily. Historians suggest that there were at least 2 reasons for such actions. First, according to legends, a female representative who died alone would never be able to find her way to the kingdom of the dead. This was the privilege of men. And, secondly, the fate of a widow in those days often became unenviable, because after the death of her husband, the woman was limited in many rights. In connection with the death of the breadwinner, she was deprived of a permanent income and for her relatives became a burden, an extra mouth in the family.

Salting children

The youngest members of the family were also subjected to numerous rituals. In addition to the so-called "baking" ritual, when the baby was put into the oven so that he was "born again", without ailments and troubles, salting was also practiced in Russia. The child's naked body was rubbed thickly with salt from head to toe, including the face, and then swaddled. The baby was left in this position for some time. Sometimes the delicate skin of a child could not withstand such torture and simply peeled off. However, the parents were not at all embarrassed by this circumstance. It was believed that with the help of salting a child can be protected from diseases and the evil eye.

The murders of the elderly

The frail elderly were not only a burden and completely useless members for their families. It was believed that old people, especially long-livers, exist only due to the fact that they suck energy from young fellow tribesmen. Therefore, the Slavs carried their relatives of old age to the mountain or took them to the forest, where the old people died of cold, hunger or from the teeth of wild predators. Sometimes, for loyalty, the elderly were tied to trees or simply beaten on the head. By the way, most often it was the old people who found themselves in the role of the victim during the sacrifices. For example, infirm people were drowned in water in order to make it rain during a drought.

"Blowing" the spouse

The ceremony of "blowing" the spouse was usually performed immediately after the wedding. The young wife had to take off her husband's shoes. It is worth noting that the Slavs since ancient times endowed the legs, and accordingly the trail that she leaves, with a variety of magical properties. For example, the boot was often used by unmarried girls for fortune telling, and fatal damage could be put on a human trail. Therefore, it is not surprising that the shoes were a kind of protection for their owner. By allowing his wife to take off his shoes, the man showed her his confidence. However, after that, the husband usually hit the woman with a whip several times. Thus, the man showed the woman that from then on she was obliged to obey him in everything. Presumably, it was then that the saying “beats, it means that he loves” appeared.

Fedot Vasilievich Sychkov (1870 -1958) "Peasant girl"

I love to walk to the pole,

I love to stir hay.

As if to see a sweetheart,

Talk for three hours.

|

|

| At haymaking. Photo. The beginning of the XX century. | B. M. Kustodiev. Haymaking. 1917. Fragment |

|

|

| A. I. Morozov. Haymaking rest. OK. I860 | Women in mowing shirts harvesting hay. Photo. The beginning of the XX century. |

|

|

| A group of young women and girls with a rake. Photo. 1915. Yaroslavl province. | Drying hay on stakes. Photo. 1920s. Leningrad region. |

Haymaking began at the very end of June: "June went through the forests with a scythe", from the day of Samson Senognoy (June 27 / July 10), from Petrov's Day (June 29 / July 12) or from the summer day of Kuzma and Demyan (July 1/14 ). The main work took place in July, the "Senozornik".

Hay was procured in flood meadows located in river valleys and on small plots of land reclaimed from the forest. Grasslands could be located both near the village and at some distance from it. The peasants went to distant meadows with their whole family: "Everyone who is old enough, hurry to the haymaking." Only old men and women remained at home to look after the little ones and take care of the livestock. This is how, for example, the peasants of the villages of Yamny, Vassa, Sosna of the Meshchovsky district of the Kaluga province went to hay in the late 1890s: “The time has come for mowing ... , with scythes, rakes, pitchforks. Almost every cart carries three or four people, of course, with children. Some are carrying a keg of kvass, jugs of milk. They are riding discharged: men in chintz shirts of all colors and the wildest imagination; young people in jackets, moreover, waistcoats ... Women imagine from their frilled sundresses and Cossack blouses in the waist such a flower garden that dazzles in their eyes. And the scarves! But it is better to keep silent about shawls: their variety and brightness is innumerable. And in addition, aprons, that is, aprons. Now there are sailors here, so you will meet a pretty peasant girl, and you might well think that this is a city girl, or, what good, a landowner. Teenagers and children also try to dress up in all the best. They're going and singing songs as hard as they can ”[Russian peasants. T. 3.P. 482).

The girls were looking forward to the hay season with great impatience. The bright sun, the proximity of water, fragrant herbs - all this created an atmosphere of joy, happiness, freedom from everyday life, and the absence of the stern eye of old people and old women - the village guards of morality - made it possible to behave somewhat more relaxed than in ordinary times.

Residents of each village, having arrived at the place, arranged a parking lot - a machine: they put up huts in which they slept, prepared firewood for a fire, on which they cooked food. There were many such machines along the banks of the river - up to seven or eight on two square kilometers. Each machine usually belonged to the inhabitants of the same village, who worked in the meadow together. The mowed and dried grass was divided by the machine according to the number of men in the family.

We got up early in the morning, even before sunrise, and without having breakfast, we went to mowing so as not to miss the time while the meadow is covered with dew, since it is easier to mow wet grass. When the sun rose higher above the horizon and the dew began to "cover", the families sat down to breakfast. On a fast day, they ate meat, bread, milk, eggs, on fast days (Wednesday and Friday) - kvass, bread and onions. After breakfast, if the dew was strong, they continued to mow, and then spread the grass in even thin rows in the meadow to dry it out. Then we dined and rested. During this time, the grass wrapped a little, and they began to stir it up with a rake so that it dries better. In the evening, the dried hay was piled up in heaps. In the common work of the family, everyone knew their job. Boys and young men were mowing the grass. Women and girls laid it out in rows, stirring it up and gathering it into heaps. Throwing haystacks was the job of boys and girls. The guys served hay on wooden pitchforks, and the girls laid it out on the haystack, crushed it with their feet so that it lay down more tightly. The evening for the older generation ended with the beating of braids with hammers on small anvils. This ringing echoed throughout the meadows, signifying that the work was over.

“The hay man knocked down the peasant's arrogance that he had no time to lie down on the stove,” says the proverb about the employment of people in the kosovishte from morning to evening. However, for boys and girls, haymaking was a time when they could demonstrate to each other the ability to work well and have fun. It is not for nothing that on the Northern Dvina the communication of young people during the haymaking season was called “beauty”.

Fun reigned at lunchtime, when the elders rested in the huts, and the youth went to bathe. The joint bathing of boys and girls was not approved by public opinion, so the girls went away from the bench, trying not to be tracked down by the guys. The guys still found them, hid their clothes, arousing the girls' indignation. They usually returned together. The girls sang to their boyfriends, for example, the following song:

It will rain, the senzo will wet,

The tatya will scold -

Help me, good one,

My germ will fly.

Frequent rain pours

My dear remembers:

- Wets my darling

In the haymaking, poor.

The main fun came in the evening, after sunset. Young people gathered to one of the machines, where there were many "glavnits". The accordion was playing, dances, songs, round dances, and festivities in pairs began. The joy of the festivities, which lasted almost until the very morning, is well conveyed by the song:

Petrovskaya night,

The night is small

And the rail, okay,

Small!

And I, young,

Didn't get enough sleep

And the rail, okay,

Didn't get enough sleep!

Didn't get enough sleep

Not walked up!

And the rail, okay,

Not walked up!

I'm with a sweet friend

Not insisted!

And the rail, okay,

Not insisted!

I did not insist

I didn’t say enough

And the rail, okay,

I didn’t say enough!

At the end of the festivities, a "collapsible" song of the girls was performed:

Let's go girls home

Dawn is studying!

Dawn is engaged

Mom will swear!

Haymaking remained “the most enjoyable of rural work” even if it took place near the village and therefore every evening it was necessary to return home. Eyewitnesses wrote: “The season, warm nights, bathing after the exhausting heat, the fragrant air of the meadows - all together have something charming, pleasantly affecting the soul. Women and girls have a custom to work in the meadows to put on not only clean linen, but even dress in a festive way. For the girls, the meadow is a gulbish, where they, working together with a rake and accompanying the work with a common song, draw themselves in front of the suitors "(Selivanov V. V. S. 53).

Haymaking ended on the feast day of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God (July 8/21) or on Ilya's Day (July 20 / August 2): "Ilya the Prophet is a deadline for mowing." It was believed that "after Ilya" the hay would not be so good: "Before Ilyin's day in the hay a pood of honey, after Ilya's day - a pood of manure."

You are reapers, you are reapers

My young ones!

Young reapers

Sickles are golden!

You reap, reap,

Reap don't be lazy!

And having squeezed the nyvka,

Drink, have fun.

The hay harvest was followed by the harvest of "grain" - this was the name of all grain crops. In different regions, the bread was ripened at different times, depending on climatic conditions. In the southern part of Russia, the harvest began already in mid-July - from the feast of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God, in the middle lane - from Ilyin's day or from the day of St. Boris and Gleb (July 24 / August b), and in the north - closer to mid-August. Winter rye was the first to ripen, followed by spring bread, oats, and then buckwheat.

Sting, stinging oats,

I switched to buckwheat.

If I see a sweetheart -

I will meet him.

Harvesting was considered a job for girls and married women. However, the main harvesters were girls. Strong, sturdy, dexterous, they easily coped with a rather difficult job.

|

|

| P. Vdovichev, Harvest. 1830th | The rye is ripe. Photo by S. A. Lobovikov. 1926-1927 |

|

|

| Reaper. Photo by S. A. Lobovikov. 1914-1916 | A.G. Venetsianov. At the harvest. Summer. Before 1827 |

The harvest was supposed to start on the same day. Before that, women chose from among their midst a healer who would perform a symbolic hedge of the field. Most often it was a middle-aged woman, a good reaper, with a "light hand". Early in the morning, secretly from everyone, she ran to the field, eaten three small sheaves, saying, for example, like this:

Shoot, half, at the end,

Like a Tatar stallion!

Run and rye, grind and tear

And look for the end by the field!

Run out, run out

Give us a will!

We came with sharp sickles

With white hands

With soft ridges!

After that, the woman laid the sheaves crosswise at the edge of the field, and next to her left a piece of bread with salt for Mother Earth and an icon of the Savior to protect the harvest from evil spirits.

The entire female half of the family, headed by the mistress, went to the harvest. Girls and women wore special harvest clothes - belted white canvas shirts, decorated with a red woven or embroidered pattern along the hem and on the sleeves. In some villages, the upper part of the shirt was sewn from bright chintz, and the lower part from canvas, which was covered with a beautiful apron. The heads were tied with calico kerchiefs. The harvest garment was very festive to match the important day when Mother Earth will give birth to the harvest. At the same time, the clothes were also comfortable for work, loose, it was not hot in it under the summer sun.

The first day of the harvest began with a common prayer of the family in their strip. The reapers worked in the field in a specific order. Ahead of all was the hostess of the house, saying: “Bless, God, to squeeze the cornfield! Give, Lord, ergot and lightness, good health! " (Folk traditional culture of the Pskov region. P. 65). On her right hand was the eldest daughter, followed by seniority were the other daughters, and after them the daughters-in-law. The first sheaf was supposed to be squeezed by the eldest daughter in the family, so that she would get married in the fall: "The first sheaf to reap is to make a groom." They believed that the first metacarpus of cut rye stalks and the first sheaf collected from them had “spore”, “sportiveness” - a special vital force, so necessary for the future mistress and mother.

The reapers went to the field after the sun dries up the dew. It was impossible to harvest bread covered with dew, so that the grain and straw would not rot before threshing. The girls went to the field together, sang songs that were called harvest songs. The main theme of the songs was unhappy love:

Early and early our courtyard is overgrown.

Overgrown-bloomed our courtyard with grass-ant.

It’s not grass in the field, not an ant, pink flowers.

There flowers bloomed in the field, bloomed, and withered.

The guy loved the red girl, but left.

Leaving the girl, he laughed at her.

Don't laugh at the girl, boy, you are still single yourself.

Single, unmarried, no wife taken.

While working, girls were not supposed to sing - it was the prerogative of only married women. Married women turned in songs to God, the field, the sun, the spirits of the field with a request for help:

Yes, take away, God, a thundercloud,

Yes, save, God, the working field.

Peasant fields (stripes) were located nearby. The reapers could see how the neighbors were working, echo each other, cheer up the tired, reproach the lazy. The songs were interspersed with the so-called whooping, that is, shouts, exclamations of "Ooh!", "Hey!" Gukanye was so strong that it could be heard in villages far from the fields. All this polyphonic noise was beautifully called "the singing of the stubble".

So that by the evening a certain part of the work was completed, the laggards were urged on: “Pull up! Pull up! Pull! Pull your goat! " Each girl tried to press more sheaves, get ahead of her friends, and not get into the laggards. They laughed at the lazy ones, shouted: “Girl! Kila to you! " - and at night on the runway negligent girls "put a keel": they stuck a stick into the ground with a bunch of straw tied to it or an old bast shoe. The quality and speed of work was used to determine whether a girl was “hard-working” and whether she would be a good housewife. If the reaper left an uncompressed groove behind her, then they said that she would have "a man with a nuttz"; if the sheaves turned out to be large, then the peasant will be big, if even and beautiful, then rich and hardworking. To make the work stand out, the girls said: "A strip to the edge, like a white rabbit, shoot, drive, shoot, drive!" (Morozov I. A., Sleptsova I. S. 119), and in order not to get tired, they girdled themselves with a flagellum of stalks with the words: "As mother rye became a year old, but she was not tired, so my back would not be tired to reap" ( Maikov L.N.S. 204).

The work ended when the sun declined and the stubble was covered with dew. It was not allowed to remain on the field after entering: according to legend, this could prevent the deceased ancestors from "walking in the fields and enjoying the harvest." Before leaving the under-pressed strip, it was supposed to put two handfuls of stems crosswise to protect it from damage. Sickles, hiding, were usually left in the field, and not carried into the house, so as not to bring rain.

After a hard day, the girls again gathered in a flock and all went to rest together, singing about unhappy love:

She sang songs, my chest ached

Heart was breaking.

Tears rolled down my face -

She parted with the darling.

Hearing loud chanting, guys appeared who flirted with the girls, counting on their favor. The guys' jokes were sometimes pretty rude. For example, the guys frightened the girls, unexpectedly attacking them from behind the bushes, or they put "gags": they tied up the tops of the grasses that grew on both sides of the path along which the girls walked. In the dark, the girls might not notice the traps, they fell, causing the guys to laugh.

Then they walked together, and the girls "sang" to the guys of the brides:

Maryushka walked with us in the garden,

We have Vasilievna green.

Ivan the good fellow looked at her:

“Here comes my precious, invaluable beauty.

I went through the whole village,

I couldn't find Maria better, better.