Creation of a story of bygone years in what century. The name of the lists "Tale of Bygone Years"

Read also

It is difficult to determine why, after centuries, and sometimes millennia, some representatives of the human race have a desire to get to the bottom of the truth, to confirm or refute some theory that has become habitual a long time ago. Unwillingness to believe without evidence in what is customary, convenient or profitable has allowed and allows new discoveries to be made. The value of such restlessness is that it contributes to the development of the human mind and is the engine of human civilization. One of these mysteries in the history of our Russian fatherland is the first Russian chronicle, which we know as.

The Tale of Bygone Years and Its Authors

Almost a millennium ago, almost the first ancient Russian chronicle began, which told about how and where the Russian people came from, how the ancient Russian state was formed. This chronicle, like the subsequent Old Russian chronicles that have come down to us, are not a chronological listing of dates and events. But it is also impossible to call the Tale of Bygone Years a book in its usual sense. It consists of several lists and scrolls, which are united by a common idea.

This chronicle is the most ancient handwritten document created on the territory of Kievan Rus and extant to our times. Therefore, modern scientists, like historians of previous centuries, are guided precisely by the facts given in the Tale of Bygone Years. It is with its help that they try to prove or question one or another historical hypothesis. It is from here that the desire to identify the author of this chronicle, in order to prove the authenticity of not only the chronicle itself, but also the events about which it tells, is also wanted.

In the original, the manuscript of the chronicle, which is called the Tale of Bygone Years, and was created in the XI century, did not reach us. In the 18th century, two copies were discovered made in the 15th century, something like a re-edition of the Old Russian chronicle of the 11th century. Rather, it is not even a chronicle, but a kind of textbook on the history of the emergence of Russia. It is generally accepted to consider it the author of Nestor, a monk of the Kiev-Pechora monastery.

Amateurs should not put forward too radical theories on this score, but anonymity was one of the postulates of medieval culture. Man was not a person in the modern sense of the word, but was just a creation of God, and only clergymen could be the conductors of God's providence. Therefore, when rewriting texts from other sources, as it happens in the Tale, the one who does it, of course, adds something from himself, expressing his attitude to certain events, but he does not put his name anywhere. Therefore, the name of Nestor is the first name that is found in the list of the 15th century, and only in one, Khlebnikovsky, as scientists called it.

The Russian scientist, historian and linguist A.A. Shakhmatov does not deny that the Tale of Bygone Years was written not by one person, but is a reworking of legends, folk songs, oral stories. It uses both Greek sources and Novgorod records. In addition to Nestor, hegumen Sylvester in the Kiev Vydubitsky Mikhailovsky monastery was engaged in editing this material. So, historically it is more accurate to say not the author of the Tale of Bygone Years, but the editor.

Fantastic version of the authorship of the Tale of Bygone Years

The fantastic version of the authorship of the Tale of Bygone Years claims that its author is the closest associate of Peter I, an extraordinary and mysterious personality, Jacob Bruce. A Russian nobleman and count with Scottish roots, a man of extraordinary erudition for his time, a secret freemason, alchemist and sorcerer. Quite an explosive mixture for one person! So new researchers of the authorship of the Tale of Bygone Years will have to deal with this, at first glance, fantastic version.

On November 9, the Orthodox Church honors the memory of the Monk Nestor the Chronicler. He is known as the compiler of the "Tale of Bygone Years" - the first Russian chronicle, which tells about the history of the Russian state and church.

Life of the Monk Nestor the Chronicler

The Monk Nestor was born about 1056 in Kiev. As a seventeen-year-old youth, he became a novice of the Kiev-Pechersk monastery with the Monk Theodosius. He took tonsure from Abbot Stephen, successor of Theodosius. While in the monastery, Nestor served as a chronicler.

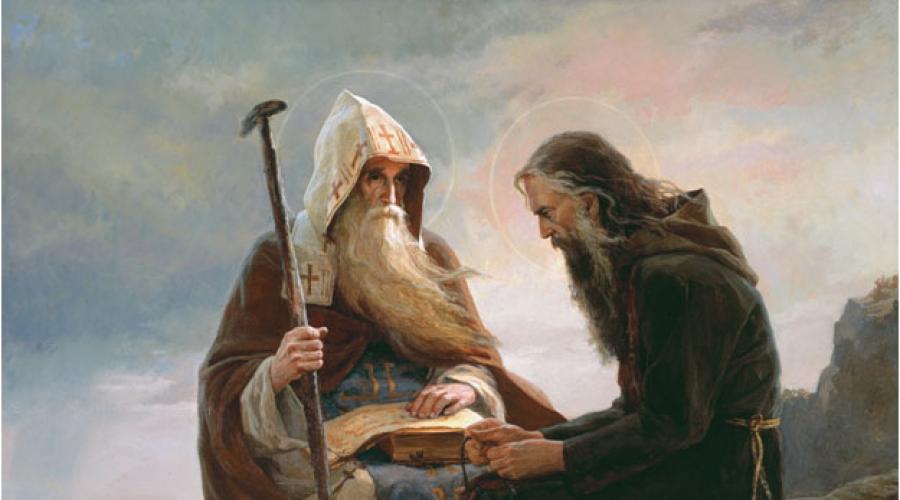

Vasnetsov's painting "Chronicler Nestor" 1919. Photo: Public Domain

Nestor died around 1114. He was buried in the Near Caves of St. Anthony of the Caves of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra. A liturgical service in his memory was compiled in 1763.

The Orthodox Church honors his memory on November 9 and October 11 - during the feast of the Cathedral of the Venerable Kievo-Pechersk Fathers in the Near Caves, as well as on the 2nd Week of Great Lent, when the Sobor of all Kievo-Pechersk Fathers is celebrated.

What is known about the writings of the chronicler?

The first written works of Nestor the Chronicler were The Life of Saints Boris and Gleb, as well as The Life of the Monk Theodosius of the Caves. His main work is considered to be the chronicle "The Tale of Bygone Years", written by him in 1113. Its full name is "Behold the tales of time years, where the Russian land came from, who in Kiev began the first princes, and from where the Russian land began to eat."

The Monk Nestor was not the only author of the "Tale"; even before him, his predecessors worked on collecting material. When compiling the chronicle, Nestor used Russian chronicles and legends, monastery records, Byzantine chronicles, various historical collections, stories of the elder boyar Yan Vyshatich, merchants, soldiers and travelers. The merit of the Monk Nestor consisted in the fact that he collected, processed and presented to the descendants his historical work and set forth in it information about the Baptism of Rus, about the creation of the Slavonic charter by the Equal-to-the-Apostles Cyril and Methodius, about the first metropolitans of the Russian Church, about the emergence of the Kiev-Pechersk monastery, about its founders and devotees.

Nestorov's "Tale" has not survived in its original form. After the death of the patron saint of the monks of the Caves Svyatopolk Izyaslavich in 1113, Vladimir Monomakh became the prince of Kiev. He came into conflict with the top of the Kiev-Pechersky Monastery and passed on the chronicles to the monks of the Vydubitsky Monastery. In 1116, Vydubytsky abbot Sylvester revised the final articles of The Tale of Bygone Years. This is how the second edition of the work appeared. The Tale of Bygone Years has survived to this day as part of the Laurentian Chronicle, the First Novgorod Chronicle and the Ipatiev Chronicle.

The Tale of Bygone Years (Primary Chronicle, Nestorov Chronicle) is one of the earliest ancient Russian annalistic collections, dating back to the beginning of the 12th century. There are several editions and lists with minor deviations from the main text. It was written in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra by her monk Nestor. Covers the period of Russian history, from biblical times to 1114.

KIEV-PECHERSK LAVRA

Kiev-Pechersk Lavra considered one of the first Orthodox monasteries of the Old Russian state. It was founded in 1051 under Prince Yaroslav the Wise. The founders of the Lavra are considered to be the monk Anthony of Lubech and his disciple Theodosius.

In the 11th century, the territory of the future Lavra was covered with a dense forest, where priest Ilarion, a resident of the nearby village of Berestovo, loved to pray. He dug for himself a small cave here, where he retired from worldly life. In 1051, Yaroslav the Wise appointed Hilarion Metropolitan of Kiev, and the cave was empty. Around the same time, monk Anthony came here from Athos. He did not like life in the Kiev monasteries, and he, together with his student Theodosius, settled in the cave of Hilarion. Gradually, a new Orthodox monastery began to take shape around Anthony's cave.

The son of Yaroslav the Wise - Prince Svyatoslav Yaroslavich - presented the newly formed monastery with the land located above the caves, and later beautiful stone temples grew here,

Anthony and Theodosius - founders of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra

In 1688 the monastery received the status of a lavra and became "the stavropegion of the Moscow Tsar and the Russian Patriarch." Lavra in Russia refers to large male Orthodox monasteries that have special historical and spiritual significance for the entire state. Since 1786, the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra was reassigned to the Kiev metropolitan, who became its holy archimandrite. Under the ground temples of the lavra there is a huge underground complex of the monastery, consisting of the Near and Far caves.

Kiev-Pechersk Lavra

The first dungeons on the territory of the Old Russian state appeared in the 10th century. These were small caves that were used by the population as storerooms or as a shelter from enemies. Beginning in the 11th century, people who wanted to get away from worldly temptations began to flock to the territory of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra, and Anthony showed them places to build underground cells.

Gradually, individual dwelling cells were connected by underground passages, caves for joint prayers, extensive storerooms and other utility rooms appeared. This is how the Far Caves arose, which are called in another way Theodosius (in memory of the Monk Theodosius, who drew up the Rule of the cave monastery).

The underground cells were erected at a depth of five to fifteen meters in a layer of porous sandstone that maintained normal humidity and a temperature of + 10 degrees Celsius underground.

The climate of the catacombs not only provided quite comfortable living conditions for people, but also prevented the decay of organic matter. Thanks to this, the mummification (formation of relics) of the deceased monks took place in the caves of the Lavra, many of whom bequeathed to be buried in the cells where they lived and prayed. These ancient burials were the first stage in the creation of an underground necropolis.

Today, there are more than 140 tombs in the lower floors of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra: 73 burials in the Near caves and 71 in the Far ones. Here, along with the graves of monks, there are burials of laymen. Thus, Field Marshal Pyotr Aleksandrovich Rumyantsev and statesman of post-reform Russia Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin were buried in the dungeons of the monastery.

Today, there are more than 140 tombs in the lower floors of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra: 73 burials in the Near caves and 71 in the Far ones. Here, along with the graves of monks, there are burials of laymen. Thus, Field Marshal Pyotr Aleksandrovich Rumyantsev and statesman of post-reform Russia Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin were buried in the dungeons of the monastery.

Very quickly, the underground monastery grew so much that it had to be expanded. Then the labyrinth of the Near Caves appeared, consisting of three "streets" with numerous dead-end branches. As often happens, the Kiev-Pechersk undergrounds quickly became overgrown with myths. Medieval authors wrote about their incredible length: some reported 100-mile long passages, others argued that some of the labyrinths were more than thousands of miles long. Now let's go back to the distant 11th century, to the time when the laurel was just beginning to be created.

In 1073, on the Kiev hills, above the caves of the monastery, the monks laid the first ground stone church, completed and consecrated in 1089. Its interior decoration was designed by the artists of Constantinople, among whom the name Alypius is known.

In 1073, on the Kiev hills, above the caves of the monastery, the monks laid the first ground stone church, completed and consecrated in 1089. Its interior decoration was designed by the artists of Constantinople, among whom the name Alypius is known.

Seven years later, the monastery, which had not yet matured, survived a terrible attack by the Polovtsians. Orthodox shrines were plundered and desecrated. But already in 1108, under the abbot Theoktistos, the monastery was restored, and new frescoes and icons adorned the walls of ground-based cathedrals.

By this time, the laurel was fenced in with a high palisade. At the temples, there was a hospice, arranged by St. Theodosius for the shelter of beggars and cripples. Every Saturday the monastery sent a cart of bread to Kiev prisons for prisoners. In the 11-12 centuries, more than 20 bishops emerged from the monastery, who served in churches throughout Russia, but at the same time retained a strong connection with their native monastery.

The Kiev-Pechersk Lavra has repeatedly been invaded by enemy armies. In 1151 it was plundered by the Turks, in 1169 the combined troops of Kiev, Novgorod, Sukhdal and Chernigov even tried to finally destroy the monastery during the princely strife. But the most terrible destruction of the Lavra happened in 1240, when the hordes of Batu took Kiev and established their rule over Southern Russia.

Under the blows of the Tatar-Mongol army, the monks of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra either died or fled to the surrounding villages. It is not known how long the desolation of the monastery lasted, but by the beginning of the 14th century it was completely restored again and became the burial place of the noble princely families of Russia.

In the 16th century, an attempt was made to subjugate the Kiev-Pechersk monastery to the Roman Catholic Church, and the monks twice had to defend the Orthodox faith with weapons in their hands. After that, having received the status of a lavra, the Kiev-Pechersky Monastery became a stronghold of Orthodoxy in South-Western Russia. To protect against enemies, the above-ground part of the lavra was first surrounded by an earthen rampart, and then, at the request of Peter the Great, by a stone wall.

Great Lavra Bell Tower

In the middle of the 18th century, next to the main temple of the Lavra, the Great Lavra Bell Tower was erected, the height of which, together with the cross, reached 100 meters. Even then, the Kiev-Pechersk monastery became the largest religious and cultural center in Russia. There was a miraculous icon of the Dormition of the Mother of God, the relics of St. Theodosius and the first Metropolitan Hilarion of Kiev. The monks have collected a large library filled with valuable religious and secular rarities, as well as a collection of portraits of the great Orthodox and statesmen of Russia.

During Soviet times (1917-1990), the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra ceased to function as an Orthodox church. Several historical and state museums were created here. During the years of the fascist occupation, the Orthodox churches of the Lavra were desecrated, in which the Germans organized warehouses and administrative structures. In 1943, the Nazis blew up the main church of the monastery - the Assumption Church. They filmed the destruction of an Orthodox shrine on film and incorporated this footage into the official German newsreel.

Nowadays, the Bandera authorities in Kiev are trying to distort this historical data, claiming that the cathedral was blown up by Soviet partisans, who somehow broke into the center of Kiev occupied by the Germans. However, the memoirs of fascist generals - Karl Rosenfelder, Friedrich Heyer, SS Obergruppenfuehrer Friedrich Ekkeln - testify that the Orthodox shrines of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra were systematically destroyed by the German occupation authorities and their minions from among the Ukrainian Banderaites.

After the liberation of Kiev by Soviet troops in 1943, the territory of the Lavra was returned to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. And in 1988, in connection with the celebration of the 1000th anniversary of the baptism of Rus, the territories of the Near and Far Caves were also returned to the monastic community of the Lavra. In 1990, the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Currently, the famous monastery is already located in the center of Kiev - on the right, high, bank of the Dnieper and occupies two hills separated by a deep hollow descending to the water. The Lower (underground) Lavra is under the jurisdiction of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, and the Upper (ground) Lavra is under the jurisdiction of the National Kiev-Pechersk Historical and Cultural Reserve.

NESTOR Chronicler

Nestor the Chronicler

(1056-1114) - Old Russian chronicler, hagiographer of the late 11th - early 12th centuries, monk of the Kiev-Pechersk Monastery. He is one of the authors of The Tale of Bygone Years, which, along with the Czech Chronicle of Kozma of Prague and the Chronicle and Deeds of Polish Princes and Rulers by Gall Anonymous, is considered the most important document in the history of ancient Slavic statehood and culture. It is also assumed that Nestor wrote "Readings on the Life and Destruction of Boris and Gleb."

Nestor the Chronicler

(1056-1114) - Old Russian chronicler, hagiographer of the late 11th - early 12th centuries, monk of the Kiev-Pechersk Monastery. He is one of the authors of The Tale of Bygone Years, which, along with the Czech Chronicle of Kozma of Prague and the Chronicle and Deeds of Polish Princes and Rulers by Gall Anonymous, is considered the most important document in the history of ancient Slavic statehood and culture. It is also assumed that Nestor wrote "Readings on the Life and Destruction of Boris and Gleb."

The author of "The Tale" and "Readings" was canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church as the Monk Nestor the Chronicler, and October 27 is considered his day of memory. Under the same name, he is included in the list of saints of the Roman Catholic Church. Nestor's relics are in the Near Caves of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra.

Order of the Reverend Nestor the Chronicler

The future author of the main Russian chronicle was born ca. 1056 and as a young man came to the Kiev-Pechersk monastery, where he was tonsured. In the monastery he carried the obedience of the chronicler. The great feat of his life was the compilation of the "Tale of Bygone Years". Nestor considered his main goal to preserve the legend for the descendants of "where did the Russian land come from, who in Kiev began the first princes and where the Russian land began to eat."

Nestor the Chronicler

Reconstruction on the skull of S.A. Nikitina

The famous Russian linguist A.A. Shakhmatov established that The Tale of Bygone Years was created on the basis of more ancient Slavic chronicles and chronicles. The original version of the "Tale" was lost in antiquity, but its revised later versions have survived, the most famous of which are contained in the Laurentian (14th century) and Ipatiev (15th century) annals. At the same time, none of them contains clear indications on which historical event Nestor the Chronicler stopped his narration.

According to the hypothesis of A.A. Shakhmatova, the oldest chronicle collection "The Tale of Bygone Years" was compiled by Nestor in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra in 1110-1112. The second edition belongs to the pen of Abbot Sylvester, abbot of the Vydubitsky monastery (1116). And in 1118, on the instructions of the Novgorod prince Mstislav Vladimirovich, the third edition of the Tale was written.

According to the hypothesis of A.A. Shakhmatova, the oldest chronicle collection "The Tale of Bygone Years" was compiled by Nestor in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra in 1110-1112. The second edition belongs to the pen of Abbot Sylvester, abbot of the Vydubitsky monastery (1116). And in 1118, on the instructions of the Novgorod prince Mstislav Vladimirovich, the third edition of the Tale was written.

Nestor was the first church historian who gave in his work a theological substantiation of Russian history, while preserving many historical facts, characteristics and documents that later formed the basis of educational and popular science literature on history. Deep spiritual saturation, the desire to faithfully convey the events of the state and cultural life of Russia and high patriotism put the "Tale of Bygone Years" on a par with the highest works of world literature.

"WHERE WAS THE RUSSIAN LAND GONE ..."

History of Russia from the time of Noah

F. Danby. Global flood.

4.5 thousand years ago “the waters of the Flood came to the earth, all the springs of the great abyss were opened, and the windows of heaven were opened, and it rained on the earth for forty days and forty nights ... Every living creature that was on the surface of the earth was destroyed; only Noah remained and what was with him in the ark ... ”(Old Testament).

For five months, the water covered the Earth by 15 cubits (cubit - 50 cm), the highest mountains disappeared into its depths, and only after this period the water began to subside. The ark stopped on the mountains of Ararat, Noah and those with him came out of the ark and released all animals and birds to breed them on Earth.

I.K. Aivazovsky. Noah leads the survivors from Ararat.

In gratitude for his salvation, Noah made a sacrifice to God and received from Him a solemn promise that in the future there will be no such terrible floods on Earth. The sign of this promise is the rainbow that appears in the sky after the rain. And then people and animals descended from the Ararat mountains and began to inhabit the deserted land.

To prevent his heirs from quarreling when settling in cities and countries, Noah divided the Earth between his three sons: Shem got the east (Bactria, Arabia, India, Mesopotamia, Persia, Media, Syria and Phenicia); Ham got possession of Africa; and the northwestern territories were ceded to Yafet. Varangians, Germans, Slavs and Swedes are named as the descendants of Yafet in the Bible.

Thus, Nestor calls the forefather of these tribes Yafet, the middle son of Noah, and emphasizes the origin of the European and Slavic peoples from one ancestor. After the Babylonian pandemonium, many peoples emerged from the single tribe of Japheth, who each received their own dialect and their lands. The ancestral home of the Slavs (noriks) in the "Tale of Bygone Years" refers to the banks of the Danube River - the countries of Illyria and Bulgaria.

During the Great Migration of Peoples (4th - 6th centuries), the Eastern Slavs, under pressure from the Germanic tribes, left the Danube and settled on the banks of the Dnieper, Dvina, Kama, Oka, as well as the northern lakes - Nevo, Ilmen and Ladoga.

Nestor connects the settlement of the Eastern Slavs with the times of the Apostle Andrew the First-Called, who stayed in their lands and after whose departure the city of Kiev was founded on the high bank of the Dnieper.

Other Slavic cities in the annals are called Novgorod (Slovenia), Smolensk (Krivichi), Debryansk (Vyatichi), Iskorosten (Drevlyane). At the same time, Ancient Ladoga was first mentioned in the Tale of Bygone Years.

Olga Nagornaya. Slav!

The calling of the Varangians to Russia

Battle ship of the Varangians - Drakkar

The initial date of the "Tale" is 852, when the Russian land was first mentioned in the chronicles of Byzantium. At the same time, the first reports appeared about the Varangians - immigrants from Scandinavia ("findrs from overseas"), who sailed on warships - Drakkars and Knorrs - in the Baltic Sea, robbing European and Slavic merchant ships. In Russian chronicles, the Varangians are represented primarily by professional warriors. Their very name, according to a number of scientists, comes from the Scandinavian word "wering" - "wolf", "robber".

Nestor reports that the Varangians were not a single tribe. Among the "Varangian peoples" he mentions Russia (the tribe of Rurik), Sveev (Swedes), Normans (Norwegians), Goths (Gotlandians), "Danes" (Danes), etc. 9th century. Somewhat later, the Constantinople Chronicles mention the Scandinavians (at the beginning of the 11th century, the Varangians appeared as mercenaries in the Byzantine army), as well as the records of the scientist Al-Biruni from Khorezm, who calls them "Varanks".

Varangian society was divided into bonds - noble people (by origin or merit to the state), free warriors and trells (slaves). The most respected of all classes were the bonds - the people who owned the land. Landless free members of society who were in the service of the king or bonds did not enjoy much respect and did not even have the right to vote at general gatherings of the Scandinavians.

Varangian society was divided into bonds - noble people (by origin or merit to the state), free warriors and trells (slaves). The most respected of all classes were the bonds - the people who owned the land. Landless free members of society who were in the service of the king or bonds did not enjoy much respect and did not even have the right to vote at general gatherings of the Scandinavians.

The emergence of free, but landless Varangians was explained by the law of inheritance of paternal property: after death, all the property of the father was transferred to the eldest son, and the younger sons had to conquer the land for themselves or earn it by faithful service to the king. For this, young landless warriors united in detachments and, in search of luck, set off on sea voyages. Armed to the teeth, they went out to sea and robbed merchant ships, and later even began to attack European countries, where they seized land for themselves.

The emergence of free, but landless Varangians was explained by the law of inheritance of paternal property: after death, all the property of the father was transferred to the eldest son, and the younger sons had to conquer the land for themselves or earn it by faithful service to the king. For this, young landless warriors united in detachments and, in search of luck, set off on sea voyages. Armed to the teeth, they went out to sea and robbed merchant ships, and later even began to attack European countries, where they seized land for themselves.

In Europe, the Varangians were known under various names, the most common of which were the names “Danes”, “Normans” and “Northerners”. The robbers themselves called themselves "Vikings", which translated as "man from the fjords" ("fjord" - "a narrow deep sea bay with steep rocky shores"). At the same time, not all inhabitants were called "Vikings" in Scandinavia, but only those who were engaged in sea robberies. Gradually the word "viking" under the influence of European languages was transformed into "viking".

The first Viking attacks on European cities began in the middle of the 8th century. One fine day, near the European shores, warships decorated with the muzzles of dragons appeared, and unknown fair-haired fierce warriors began to plunder the coastal settlements of Germany, England, France, Spain and other states.

For their time, Viking ships were very fast. So, a drakkar, going under sails, could reach a speed of 12 knots. Built in the 20th century according to ancient drawings, such a ship was able to cover a distance of 420 kilometers in a day. Possessing such transport, the sea robbers did not fear that the Europeans would be able to catch up with them on the water.

In addition, for orientation in the open sea, the Scandinavians had astrolabes, with the help of which they could easily determine the path through the stars, as well as an unusual "compass" - a piece of the mineral cordierite, which changed its color depending on the position of the Sun and the Moon. The sagas also mention real compasses, consisting of small magnets attached to a piece of wood or dipped in a bowl of water.

In addition, for orientation in the open sea, the Scandinavians had astrolabes, with the help of which they could easily determine the path through the stars, as well as an unusual "compass" - a piece of the mineral cordierite, which changed its color depending on the position of the Sun and the Moon. The sagas also mention real compasses, consisting of small magnets attached to a piece of wood or dipped in a bowl of water.

Attacking a merchant ship, the Vikings first fired at it with bows or simply threw stones at it, and then went on boarding. It is known that the bows of the barbarians could easily hit the target at a distance of 250 to 400 meters. But in most cases, the outcome of the battle depended on the maritime skill of the attackers and their ability to wield melee weapons - axes, spears, daggers and shields.

Starting with attacks on individual merchant ships, the Vikings soon moved on to raid coastal regions of Europe. The small draft of the ships allowed them to lift up navigable rivers and plunder even cities lying far from the sea coast. The barbarians were fluent in hand-to-hand fighting techniques and always easily dealt with the local militia trying to defend their homes.

The royal cavalry was much more dangerous for the Scandinavians. To hold back the onslaught of the knights chained in iron, the Vikings formed a dense formation, reminiscent of a Roman phalanx: a wall of solid shields appeared in front of the cavalry rushing on them, protecting them from arrows and swords. At first, such a fighting technique brought success, but then the knights learned to break through the barbarian defenses with the help of heavy cavalry and chariots, reinforced on the sides with thick pointed spears.

The royal cavalry was much more dangerous for the Scandinavians. To hold back the onslaught of the knights chained in iron, the Vikings formed a dense formation, reminiscent of a Roman phalanx: a wall of solid shields appeared in front of the cavalry rushing on them, protecting them from arrows and swords. At first, such a fighting technique brought success, but then the knights learned to break through the barbarian defenses with the help of heavy cavalry and chariots, reinforced on the sides with thick pointed spears.

At first, the Vikings avoided major battles with European armies. As soon as they saw an enemy army on the horizon, they quickly loaded onto ships and sailed into the open sea. But later the barbarians began to erect well-fortified fortresses on the land captured during the attack, which served as strongholds for new raids. In addition, they created special berserker strike squads in their troops.

Berserkers differed from other warriors in their ability to enter a state of uncontrollable rage, which made them very dangerous opponents. Europeans considered berserkers such a terrible "weapon" that in many countries these frenzied warriors were outlawed. Until now, it has not been precisely established with the help of which the berserkers entered a state of combat madness.

Berserkers differed from other warriors in their ability to enter a state of uncontrollable rage, which made them very dangerous opponents. Europeans considered berserkers such a terrible "weapon" that in many countries these frenzied warriors were outlawed. Until now, it has not been precisely established with the help of which the berserkers entered a state of combat madness.

In 844, the Vikings landed for the first time in southern Spain, where they sacked several Muslim cities, including Seville. In 859, they broke into the Mediterranean and devastated the coast of Morocco. It got to the point that the emir of Cordoba had to ransom his own harem from the Normans.

Soon all of Europe fell under the blows of fierce sea robbers. The bells of the church bells warned the population about the danger threatening from the sea. When the Scandinavian ships approached, people left their homes in droves, hid in the catacombs, and fled to monasteries. But the monasteries soon ceased to serve as protection for the civilian population, as the Vikings began to plunder Christian shrines as well.

Soon all of Europe fell under the blows of fierce sea robbers. The bells of the church bells warned the population about the danger threatening from the sea. When the Scandinavian ships approached, people left their homes in droves, hid in the catacombs, and fled to monasteries. But the monasteries soon ceased to serve as protection for the civilian population, as the Vikings began to plunder Christian shrines as well.

In 793, the Normans, led by Eric the Bloody Ax, plundered a monastery on one of the English islands. The monks who did not have time to escape were either drowned or enslaved. After this raid, the monastery fell into complete desolation.

In 860, the Scandinavians made several raids into Provence and then sacked the Italian city of Pisa. From other European countries at this time, the Netherlands suffered greatly, completely unprotected from attack from the sea. Bands of sea robbers also rose along the rivers Rhine and Meuse and attacked the lands of Germany.

In 865, the Danes captured and plundered the English city of York, but did not go back to Scandinavia, but settled in the vicinity of the city and engaged in peaceful farming. They imposed taxes on the English population and calmly stuffed their own money thanks to this.

In 885, the Vikings laid siege to Paris, approaching it on battle drakkars along the Seine. The army of the Normans was located on 700 ships and amounted to 30 thousand people. All the inhabitants of Paris rose to defend the city, but the forces were unequal. And only consent to a shameful and humiliating peace saved Paris from total destruction. The Vikings received large land holdings in France for their use and imposed tribute on the French.

By the middle of the 9th century, they ruled not only in the coastal territories of Europe, but also successfully attacked cities located at large distances from the Baltic coast: Cologne (200 km from the sea), Bonn (240 km), Koblenz (280 km), Mainz (340 km), Trier (240 km). Only a century later, Europe with great difficulty was able to stop the raids of the barbarians on their lands.

Ancient Novgorod

In Eastern Europe, in the lands of the Slavs, the Vikings appeared in the middle of the 9th century. The Slavs called them Varangians. European chronicles describe how in 852 the Danes laid siege to and plundered the Swedish capital city of Birka. However, the Swedish king Anund managed to buy off the barbarians and send them towards the Slavic lands. Danes on 20 ships (50-70 people on each) rushed to Novgorod.

The first to come under their attack was a small Slavic town, the inhabitants of which were unaware of the invasion of the Scandinavians and could not fight back. The same European chronicles describe how, "having unexpectedly attacked its inhabitants, who lived in peace and silence, the Danes seized it by force of arms and, taking great spoils and treasures, returned home." By the end of the 850s, all of northern Russia was already under the Varangian yoke and was imposed with a heavy tribute.

And then let us turn to the pages of the Novgorod chronicles: "The people who endured a great burden from the Varangians sent to Burivaya to ask him for the son of Gostomysl to reign in the Great City." The Slavic prince Burivy is hardly mentioned in the annals, but Russian chroniclers tell about his son Gostomysl in more detail.

I. Glazunov. Gostomysl.

Burivy, presumably, reigned in one of the earliest Russian cities - Byarme, which the Novgorodians called Korela, and the Swedes called Keskholm (now it is the city of Priozersk, Leningrad Region).

Burivy, presumably, reigned in one of the earliest Russian cities - Byarme, which the Novgorodians called Korela, and the Swedes called Keskholm (now it is the city of Priozersk, Leningrad Region).

Byarma was located on the Karelian Isthmus and in ancient times was considered a large trade center. Hence the Novgorodians asked for the reign of Burivoy's son, Prince Gostomysl, knowing him as a wise man and a brave warrior. Gostomysl, without delay, entered Novgorod and assumed the princely power.

“And when Gostomysl took power, immediately the Vikings, who were on the Russian land, whom they beat up, which they drove out, and refused to pay tribute to the Vikings, and, having gone to them, Gostomysl won, and built a city in the name of the eldest son of his Choice at the sea, concluded peace with the Varangians, and there was silence throughout the land.

“And when Gostomysl took power, immediately the Vikings, who were on the Russian land, whom they beat up, which they drove out, and refused to pay tribute to the Vikings, and, having gone to them, Gostomysl won, and built a city in the name of the eldest son of his Choice at the sea, concluded peace with the Varangians, and there was silence throughout the land.

This Gostomysl was a man of great courage, the same wisdom, all the neighbors were afraid of him, and the Slovene loved, the trial of cases for the sake of justice. For this reason, all the close peoples honored him and gave gifts and tributes, buying the world from him. Many princes from distant countries came by sea and land to listen to wisdom, and to see his judgment, and ask for his advice and his teachings, since he was glorified everywhere. "

So, Prince Gostomysl, who headed the Novgorod land, managed to expel the Danes. On the shores of the Gulf of Finland, in honor of his eldest son, he built the city of Vyborg, and around it erected a chain of fortified settlements to protect against the attack of sea robbers. According to The Tale of Bygone Years, this happened in 862.

But after that, the world did not stay on Russian soil for long, since a struggle for power began between the Slavic clans: clan, and they had strife, and began to fight with each other. " The outbreak of internecine war was brutal and bloody, and its main events unfolded on the banks of the Volkhov River and around Lake Ilmen.

The burnt settlements recently discovered by archaeologists on the territory of the Novgorod region are vivid evidence of this war. This is also indicated by the traces of a large fire discovered during excavations in Staraya Ladoga. The buildings of the city were destroyed in a total fire. Apparently, the destruction was so great that the city had to be rebuilt.

The burnt settlements recently discovered by archaeologists on the territory of the Novgorod region are vivid evidence of this war. This is also indicated by the traces of a large fire discovered during excavations in Staraya Ladoga. The buildings of the city were destroyed in a total fire. Apparently, the destruction was so great that the city had to be rebuilt.

At about the same time, the Lyubshan Fortress on the Baltic Sea coast ceases to exist. Archaeological evidence suggests that the last time the fortress was taken was not by the Vikings, since all the arrowheads found belong to the Slavs.

The Novgorod chronicles indicate that the Slavs suffered heavy losses in this war: all four sons of Prince Gostomysl perished in strife, and the destruction of Old Ladoga caused great damage to the Novgorod economy, since this city was a large economic center of Northern Russia, through which the trade route passed “from the Varangians to the Greeks.

After all the direct heirs of the Russian throne perished in bloody strife, the question arose of who would "own the land of Ruska." The aged Gostomysl met with the main wise men of Novgorod and after a long conversation with them decided to call the son of his middle daughter - Rurik, whose father was the Varangian king, to Russia. In the Joachim Chronicle, this episode is described as follows:

“Gostomysl had four sons and three daughters. His sons were either killed in the wars, or died in the house, and not a single son remained, and his daughters were given to the Varangian princes as wives. And Gostomysl and the people were grieving about this, Gostomysl went to Kolmogard to inquire of the gods about the heritage and, ascending to a high place, made many sacrifices and gave the Magi. The Magi answered him that the gods promise to give him an inheritance from the womb of his woman.

But Gostomysl did not believe this, for he was old and his wives did not give birth to him, and therefore he sent for the wise men to ask them to decide how he should inherit from his descendants. But he, not having faith in all this, was in sorrow. However, in the afternoon he slept in a dream, how from the womb of his middle daughter Umila a great fruitful tree grows and covers the entire Great City, from its fruits the people of the whole earth are satisfied.

But Gostomysl did not believe this, for he was old and his wives did not give birth to him, and therefore he sent for the wise men to ask them to decide how he should inherit from his descendants. But he, not having faith in all this, was in sorrow. However, in the afternoon he slept in a dream, how from the womb of his middle daughter Umila a great fruitful tree grows and covers the entire Great City, from its fruits the people of the whole earth are satisfied.

Rising from sleep, Gostomysl summoned the Magi and told them this dream. They decided: "He should inherit from her sons, and the land should be enriched with his reign." And everyone rejoiced that the son of the eldest daughter would not inherit, for he was worthless. Gostomysl, anticipating the end of his life, summoned all the elders of the land from the Slavs, Rus, Chud, Ves, Mer, Krivich and Dryagovich, told them a dream and sent the chosen ones to the Varangians to ask the prince. And after the death of Gostomysl Rurik came with two brothers and their relatives. "

Gostomysl ambassadors "are calling Rurik and his brothers to Russia"

About Rurik (d. 872) the Novgorod chronicles give very short and contradictory information. Presumably, he was the son of the Danish king and princess of Novgorod Umila, the grandson of Prince Gostomysl. By the time he was called to Russia, Rurik with a detachment of Varangians was known throughout Europe: he took an active part in raids on European cities, where he earned the nickname "the plague of Christianity."

The choice of the Novgorodians was not accidental, since Rurik was widely known as an experienced and brave warrior capable of defending his possessions from the enemy. In Russia, he became the first prince of the united northern Slavic tribes and the founder of the royal dynasty of Rurikovich.

M.V. Lomonosov wrote that “the Varangians and Rurik with their kin, who came to Novgorod, were Slavic tribes, spoke the Slavic language, came from ancient Ross and were by no means from Scandinavia, but lived on the eastern-southern shores of the Varangian Sea, between the Vistula and Dvina rivers ".

Monument to Rurik in Veliky Novgorod

Rurik came to Russia with his younger brothers - Truvor and Sineus. The chronicle says: "And the eldest, Rurik, came and sat in Novgorod, and the other, Sineus, was at Beloozero, and the third, Truvor, was in Izborsk." After the death of Gostomysl, the brothers faithfully served the Russian land, repelling any encroachments on its lands both from the Varangians and from other peoples. Two years later, both brothers of Rurik died in battles with enemies, and he began to rule alone in the Novgorod land.

During his reign, Rurik put things in order in his lands, established solid laws and significantly expanded the territory of the Novgorod land by joining neighboring tribes - Krivichi (Polotsk), Finno-Ugrians and Mary (Rostov), Murom (Murom) ... Under the year 864, the Nikon Chronicle reports on an attempt to incite a new internecine war in the Novgorod land, initiated by the Novgorod boyars led by Vadim the Brave. Rurik successfully suppressed their uprising and until 872 solely ruled Veliky Novgorod and the lands belonging to him.

Oleg the Prophet

The Tale of Bygone Years further informs that in 872 Rurik died, leaving his three-year-old son Igor as heir to the throne. Uncle Igor, one of the closest associates of his father, the noble warrior Oleg (d. 912), became regent under him. Continuing the policy of Rurik, Oleg expanded and strengthened the territory of Northern Russia.

He possessed the talent of an outstanding commander, was brave and courageous in battle. His ability to foresee the future and his luck in any business amazed his contemporaries. The warrior-prince was nicknamed the Prophet and enjoyed great respect among his fellow tribesmen.

At this time, in the southern Slavic lands, another state union was formed and strengthened - South Russia. Kiev became its main city. Power here belonged to two Varangian warriors who fled from Novgorod and headed the local tribes - Askold and Dir. Tradition reports that, dissatisfied with Rurik's policy, these Varangians asked him to go on a campaign to Constantinople, but seeing on the way on the banks of the Dnieper the town of Kiev, they remained in it and began to own the lands of the meadows.

Askold and Dir constantly fought with neighboring Slavic tribes (Drevlyans and Uglichs), as well as with Danube Bulgaria. Gathering around them many fugitive Varangian warriors, in 866, on 200 boats, they even embarked on a campaign against Byzantium, which is mentioned in the Byzantine chronicles. The campaign was unsuccessful: during a strong storm, most of the ships were lost, and the Varangians had to return to Kiev.

Askold and Dir constantly fought with neighboring Slavic tribes (Drevlyans and Uglichs), as well as with Danube Bulgaria. Gathering around them many fugitive Varangian warriors, in 866, on 200 boats, they even embarked on a campaign against Byzantium, which is mentioned in the Byzantine chronicles. The campaign was unsuccessful: during a strong storm, most of the ships were lost, and the Varangians had to return to Kiev.

The Kievans, like all glades, did not like Askold and Dir for their arrogance and contempt for Slavic customs. In the "Veles book" there is a message that, having adopted Christianity under the influence of Byzantium, both princes spoke with contempt of the pagan faith and humiliated the Slavic gods.

Ancient Kiev

For three years Oleg ruled in Novgorod, after which he decided to go to South Russia and annex it to his possessions. Having recruited a large army from the tribes subject to him, he put him on ships and moved along the rivers to the south. Soon Smolensk and Lyubech passed under the rule of the Novgorod prince, and after a while Oleg approached Kiev.

In an effort to avoid unnecessary losses, the prince decided to conquer Kiev by cunning. He hid the boats with the soldiers behind the high bank of the Dnieper and, approaching the gates of Kiev, called himself a merchant going to Greece. Askold and Dir entered into negotiations, but were immediately surrounded by Novgorodians.

I. Glazunov. Oleg and Igor.

Raising little Igor in his arms, Oleg told them: “You are not princes and not a princely family. Here is the son of Ruriks! " After that Askold and Dir were killed and buried on the Dnieper hill. And to this day this place is called Askold's grave.

Raising little Igor in his arms, Oleg told them: “You are not princes and not a princely family. Here is the son of Ruriks! " After that Askold and Dir were killed and buried on the Dnieper hill. And to this day this place is called Askold's grave.

So, in 882, the unification of Northern and Southern Russia into a single Old Russian state took place, the capital of which was Kiev.

Having established himself on the Kiev throne, Oleg continued Rurik's work to expand the territory of Rus. He conquered the tribes of Drevlyans, northerners, Radimichi and imposed tribute on them. A huge territory was under his rule, on which he founded many cities. The famous trade route "from the Slavs to the Greeks" passed through the lands of Ancient Rus. The boats of Russian merchants sailed along it to Byzantium and Europe. Russian furs, honey, pedigree horses and many other goods of the Rus were well known throughout the medieval civilized world.

Byzantium, the superpower of the medieval world, sought to limit the trade relations of the Old Russian state both on its territory and on the lands of neighboring countries. The Greek emperors were afraid of the strengthening of the Slavs and in every possible way prevented the growth of the economic power of Russia. For the Slavs, trade with Europe and with Byzantium itself was very important. Having exhausted diplomatic methods of struggle, Oleg decided to put pressure on Byzantium with weapons.

In 907, having equipped two thousand warships and collecting a huge cavalry army, he moved these forces to Constantinople. Until the Black Sea, Russian boats sailed along the Dnieper, and horse detachments went along the coast. Having reached the Black Sea coast, the cavalry went over to ships, and all this army rushed to the capital of Byzantium - Constantinople, which the Slavs called Constantinople.

“The tale of bygone years about this event is written as follows:“ In the year 907. Oleg went to the Greeks, leaving Igor in Kiev; He took with him a multitude of Varangians, and Slavs, and Chudi, and Krivichi, and Meru, and Drevlyans, and Radimichs, and Polyans, and Northerners, and Vyatichi, and Croats, and Dulebs, and Tivertsy, known as the Tolmachi: all of them were called Greeks "Great Scythia".

Having received a report about the approach to the Byzantine shores of the Russian fleet, Emperor Leo the Philosopher ordered to hastily lock the harbor. Powerful iron chains were stretched from one of its banks to the other, blocking the path of Russian ships. Then Oleg landed his troops ashore near Constantinople. He ordered his soldiers to make wheels from wood and put warships on them.

Waiting for a favorable wind, the soldiers raised their sails on the masts, and the boats rushed to the city by land, as if by sea: “And Oleg ordered his soldiers to make wheels and put ships on wheels. And when a fair wind blew, they raised sails in the field and went to the city. The Greeks, seeing this, were frightened and said, sending to Oleg: "Do not destroy the city, we will give you the tribute you want." And Oleg stopped the soldiers, and brought him food and wine, but did not accept it, since it was poisoned. And the Greeks were frightened, and said: "This is not Oleg, but Saint Dmitry, sent against us by God."

And the Greeks agreed, and the Greeks began to ask the world not to fight the Greek land. Oleg, moving slightly away from the capital, began negotiations for peace with the Greek kings Leon and Alexander and sent his soldiers Karl, Farlaf, Vermud, Rulav and Stemis to the capital with the words: "Pay me tribute." And the Greeks said: "What you want, we will give you." And Oleg ordered to give his soldiers 2,000 ships for 12 hryvnia per rowlock, and then give tribute to Russian cities: first of all for Kiev, then for Chernigov, for Pereyaslavl, for Polotsk, for Rostov, for Lyubech and for other cities: for by these cities sit the grand dukes, subject to Oleg. "

And the Greeks agreed, and the Greeks began to ask the world not to fight the Greek land. Oleg, moving slightly away from the capital, began negotiations for peace with the Greek kings Leon and Alexander and sent his soldiers Karl, Farlaf, Vermud, Rulav and Stemis to the capital with the words: "Pay me tribute." And the Greeks said: "What you want, we will give you." And Oleg ordered to give his soldiers 2,000 ships for 12 hryvnia per rowlock, and then give tribute to Russian cities: first of all for Kiev, then for Chernigov, for Pereyaslavl, for Polotsk, for Rostov, for Lyubech and for other cities: for by these cities sit the grand dukes, subject to Oleg. "

The frightened Greeks, having agreed to all of Oleg's conditions, signed an agreement on trade and peace. Drawn up in Russian and Greek, this treaty provided Russia with great advantages:

Oleg nails his shield on the gates of Constantinople. Engraving by F.A. Bruni, 1839

Oleg ruled in Russia for 33 years. Major historical events in the history of our state are associated with his name:

- he significantly increased the territory of the country; his power was recognized by the tribes of the Polyans, Northerners, Drevlyans, Ilmen Slovens, Krivichi, Vyatichi, Radimichi, Ulichi and Tivertsy;

- through his governors and vassals, Oleg started state building - the creation of a management apparatus and judicial and tax systems; at the conclusion of the treaty of 907 with Byzantium, the legal document of the Slavs that has not come down to us is already mentioned - "Russian Law"; annual detours of the lands subject to Oleg to collect tribute (polyudye) laid the foundation for the tax power of the Russian princes;

- Oleg led an active foreign policy; he dealt a strong blow to the Khazar Kaganate, which, having seized the southern sections of the trade route "from the Varangians to the Greeks," collected huge duties from Russian merchants for two centuries; when the Hungarians appeared near the borders of Russia, migrating from Asia to Europe, Oleg managed to establish peaceful relations with them, thereby protecting his people from unnecessary clashes with these warlike tribes; under the command of Oleg, the strongest power of the Middle Ages was defeated - the Byzantine Empire, which recognized the power of Russia and agreed to a trade agreement that was unfavorable for itself;

- under the leadership of Oleg, the core of the Old Russian state was laid and its international authority was consolidated; the European powers recognized the state status of Rus and built their relations with it on the basis of equality and military parity.

M.V. Lomonosov considered Prince Oleg a great commander, the first truly Russian ruler, about whom A.S. Pushkin will write: “Your name is glorified by victory. Your shield is at the gates of Constantinople! " In 912, Prince Oleg, bitten by a poisonous snake, died, and the place of his burial is unknown today. But there is a mound near Staraya Ladoga on the Baltic Sea coast, which is still called the Grave of Prophetic Oleg. According to the Novgorod chronicles, it is here that the legendary Slavic prince, the founder of the Old Russian state, lies.

Prince Igor and Princess Olga

Igor Rurikovich (878-945), according to legend, was the son of Rurik and Efanda, a Varangian princess and the beloved wife of a Russian prince.

Igor Rurikovich (878-945), according to legend, was the son of Rurik and Efanda, a Varangian princess and the beloved wife of a Russian prince.

After the death of his father, Igor was brought up by Oleg the Prophet and received the princely throne only after his death. He ruled in Kiev from 912 to 945.

Even during Oleg's life, Igor married the beautiful Olga, who, according to the Orthodox Life, was the daughter of a Scandinavian ("from the Varangian language"). She was born and raised in the village of Vybuty, located 12 kilometers from Pskov on the banks of the Velikaya River. In Scandinavian languages, the name of the future Russian princess sounds like Helga.

V.N. Tatishchev (1686-1750) - famous Russian historian and statesman, author of "History of Russia from the most ancient times."

He believes that Prince Oleg brought Olga to wife Igor from Izborsk and that the young 13-year-old bride belonged to the noble family of Gostomysl. The girl's name was Prekras, but Oleg renamed her Olga.

Subsequently, Igor had other wives, since the pagan faith welcomed polygamy, but Olga for Igor always remained the only assistant in all his state affairs. According to "History" V.N. Tatishchev, Olga and Igor had a son, Svyatoslav, the legal heir to the Russian throne. But, according to the chronicles, Igor also had a son, Gleb, who was executed by the Slavs for adherence to Christianity.

Having become the Grand Duke of Kiev, Igor continued the policy of Oleg the Prophet. He expanded the territory of his state and pursued a rather active foreign policy. In 914, having set out on a campaign against the rebellious Drevlyans, Igor confirmed his power in the Slavic lands and imposed a heavier tribute on the recalcitrant Drevlyans than under Oleg.

Having become the Grand Duke of Kiev, Igor continued the policy of Oleg the Prophet. He expanded the territory of his state and pursued a rather active foreign policy. In 914, having set out on a campaign against the rebellious Drevlyans, Igor confirmed his power in the Slavic lands and imposed a heavier tribute on the recalcitrant Drevlyans than under Oleg.

A year later, nomadic hordes of Pechenegs appeared on the lands of Russia for the first time, going to the aid of Byzantium against the barbarians, and Igor fought with them several times, demanding the recognition of the power of Kiev. But one of the main events in the activities of this prince was the military campaigns against Constantinople, the purpose of which was to confirm the trade agreements concluded by Prince Oleg.

On June 11, 941, ten thousand Russian warships approached Constantinople, threatening the Greeks with a siege. But by this time, the Byzantine emperors already had at their disposal the latest weapon - Greek fire.

Greek fire ("liquid fire") was a combustible mixture used by the Byzantine army to destroy enemy warships. The prototype of this weapon was used by the ancient Greeks back in 190 BC during the defense of the island of Rhodes from the troops of Hannibal. However, this formidable weapon was invented much earlier. In 424 BC, in a land battle at Delia, ancient Greek soldiers fired from a hollow log at the Persian army some kind of incendiary mixture consisting of crude oil, sulfur and oil.

Officially, the invention of Greek fire is attributed to the Greek engineer and architect Kalinnik, who in 673 tested it and, fleeing from Heliopolis captured by the Arabs (modern Baalbek in Lebanon), offered his invention to the Byzantine emperor. Kalinnik created a special device for throwing an incendiary mixture - a "siphon", which was a copper pipe, throwing out a burning liquid stream with the help of bellows.

Officially, the invention of Greek fire is attributed to the Greek engineer and architect Kalinnik, who in 673 tested it and, fleeing from Heliopolis captured by the Arabs (modern Baalbek in Lebanon), offered his invention to the Byzantine emperor. Kalinnik created a special device for throwing an incendiary mixture - a "siphon", which was a copper pipe, throwing out a burning liquid stream with the help of bellows.

Presumably, the maximum range of such siphons was 25-30 meters, so most often Greek fire was used in the fleet at the time of the approach of ships during a battle. According to the testimony of contemporaries, Greek fire posed a mortal threat to wooden ships. It could not be extinguished, it continued to burn even in water. The recipe for its manufacture was kept in strict secrecy, and after the fall of Constantinople it was completely lost.

The exact composition of this incendiary mixture is not known today. Marco Greco in his "Book of Fire" gives the following description: "1 part of rosin, 1 part of sulfur, 6 parts of saltpeter in finely ground form, dissolve in linseed or laurel oil, then put in a pipe or in a wooden trunk and light. The charge immediately flies in any direction and destroys everything with fire. " It should be noted that this composition only served to eject a fiery mixture in which an "unknown ingredient" was used.

Greek fire was, among other things, an effective psychological weapon: fearing it, enemy ships tried to keep their distance from the Byzantine ships. The Greek fire siphon was usually installed on the bow of the ship, and sometimes the fiery mixture was thrown onto enemy ships in barrels. Ancient chronicles report that as a result of careless handling of these weapons, Byzantine ships often caught fire.

Greek fire was, among other things, an effective psychological weapon: fearing it, enemy ships tried to keep their distance from the Byzantine ships. The Greek fire siphon was usually installed on the bow of the ship, and sometimes the fiery mixture was thrown onto enemy ships in barrels. Ancient chronicles report that as a result of careless handling of these weapons, Byzantine ships often caught fire.

It was with this weapon, which the Eastern Slavs had no idea about, and Prince Igor had to face in 941. In the very first sea battle with the Greeks, the Russian fleet was partially destroyed by the flaming mixture. Leaving Constantinople, Igor's troops tried to take revenge in land battles, but were driven back to the coast. In September 941, the Russian army returned to Kiev. The Russian chronicler narrates the words of the surviving soldiers: “As if the Greeks had heavenly lightning and, letting it go, they burned us; therefore they did not overcome them. "

In 944, Igor gathered a new army from the Slavs, Varangians and Pechenegs and again went to Constantinople. The cavalry, as under Oleg, went along the coast, and then the troops were put on boats. Warned by the Bulgarians, the Byzantine emperor Roman Lakapin sent noble boyars to meet Igor with the words: "Do not go, but take the tribute that Oleg took, and I will add to that tribute."

Negotiations between the Slavs and Greeks ended with the signing of a new military-trade agreement (945), according to which between Russia and Byzantium "eternal peace was established while the sun was shining and the whole world was standing." The contract first used the term “Russian land”, and also mentioned the names of Igor’s wife, Olga, his nephews and son Svyatoslav. Byzantine chronicles report that by this time some of Igor's warriors had already been baptized and, signing the agreement, swore on the Christian Bible.

Polyudye in Ancient Russia

In the fall of 945, upon returning from the campaign, Igor's squad, as usual, went to the Drevlyansky land at polyudye (collecting tribute). Having received the due gifts, the soldiers, dissatisfied with the content, demanded that the prince return to the Drevlyans and take another tribute from them. The Drevlyans did not participate in the campaign against Byzantium, perhaps that is why Igor decided to improve his financial situation at their expense.

“The Tale of Bygone Years” says: “After thinking it over, the prince said to his squad:“ Go home with a tribute, and I will return and look again. ” And he sent his squad home, and he returned with a small part of the squad, wanting more wealth. The Drevlyans, having heard that it was coming again, held a council with their prince Mal: “If a wolf gets into the habit of the sheep, he will carry out the whole flock until they kill him; so this one: if we do not kill him, then we will all ruin. "

The rebellious Drevlyans, led by Prince Mal, attacked Igor, killed his companions, and Igor was tied to the tops of two trees and torn in two. This was the first popular uprising in Russia against the princely power, recorded in the annals.

Olga, having learned about the death of her husband, in a rage took cruel revenge on the Drevlyans. After collecting a tribute from each house of the Drevlyans, one pigeon and one sparrow, she ordered tow to be tied to the paws of birds and set on fire. Pigeons and sparrows each flew to his own house and spread fire across the capital of the Drevlyans, the city of Iskorosten. The city was burnt to the ground.

Olga, having learned about the death of her husband, in a rage took cruel revenge on the Drevlyans. After collecting a tribute from each house of the Drevlyans, one pigeon and one sparrow, she ordered tow to be tied to the paws of birds and set on fire. Pigeons and sparrows each flew to his own house and spread fire across the capital of the Drevlyans, the city of Iskorosten. The city was burnt to the ground.

After that, Olga destroyed all the nobility of the Drevlyans and killed many ordinary people in the Drevlyansky land. Having imposed a heavy tribute on the disobedient, she, nevertheless, had to streamline the collection of taxes in the subject lands in order to avoid similar uprisings in the future. By her order, clear-cut amounts of taxes were established and special graveyards were built throughout Russia to collect them. After the death of her husband, Olga became regent under her young son Svyatoslav and until his adulthood ruled the country independently.

In 955, according to The Tale of Bygone Years, Princess Olga, against the will of her son Svyatoslav, was baptized in Constantinople under the name of Helena and returned to Russia as a Christian. But all her attempts to accustom her son to the new faith met with his sharp protest. Olga, thus, became the first ruler of Russia to be baptized, although the squad, the heir son, and the entire Russian people remained pagans.

On July 11, 969 Olga died, "and her son and her grandchildren and all the people wept for her with great lamentation." According to the will, the Russian princess was buried according to Christian tradition, without a funeral feast.

And in 1547 the Russian Orthodox Church declared her a saint. Only five women in the world, besides Olga, were honored with this honor: Mary Magdalene, the first martyr Thekla, the Greek queen Elena, the martyr Apphia and the Georgian queen-educator Nina.

On July 24, we celebrate the day of this great Russian woman, who, after the death of her husband, preserved all the achievements of the previous princely power, strengthened the Russian state, raised a son-commander and was one of the first to bring the Orthodox faith to Russia.

Prince Svyatoslav Igorevich (942-972)

Formally, Svyatoslav became the Grand Duke of Kiev in 945, immediately after the death of his father, but in reality his independent reign began around 964, when the prince came of age. He was the first Russian prince with a Slavic name, and thanks to him, Europe for the first time saw up close the power and courage of the Russian squads.

Formally, Svyatoslav became the Grand Duke of Kiev in 945, immediately after the death of his father, but in reality his independent reign began around 964, when the prince came of age. He was the first Russian prince with a Slavic name, and thanks to him, Europe for the first time saw up close the power and courage of the Russian squads.

From childhood, Svyatoslav was brought up as a warrior. Varangian Asmud was his mentor in matters of military skill. He taught the little prince to always be the first - both in battle and in the hunt, to hold firmly in the saddle, to be able to control a battle boat and swim well, as well as to hide from enemies in the forest and in the steppe. And Svyatoslav learned military leadership from another Varangian - the Kiev governor Sveneld.

As a child, Svyatoslav took part in the battle with the Drevlyans, when Olga led her troops to the Drevlyane city of Iskorosten. In front of the Kiev squad, a little prince was sitting on a horse, and when both troops converged for battle, Svyatoslav was the first to throw a spear at the enemy. He was still small, and the spear, flying between the ears of the horse, fell at his feet. Sveneld turned to the friendship and said: "The prince has already begun, let's follow, the squad, for the prince!" This was the custom of the Rus: only a prince could start a battle, and no matter what age he was at the same time.

The Tale of Bygone Years reports about the first independent steps of the young Svyatoslav, beginning in 964: “When Svyatoslav grew up and matured, he began to gather many brave warriors, and he was fast, like Pardus, and fought a lot. On campaigns, however, he did not carry either carts or cauldrons with him, did not cook meat, but, having thinly sliced horse meat, or animals, or beef and roasted on coals, he ate like that; he did not have a tent, but slept, spreading a saddle-cloth with a saddle in their heads - the same were all his other soldiers. And, setting out on a campaign, he sent his warrior to other lands with the words: "I am going to you!" ".

After the death of Princess Olga, Svyatoslav faced the task of organizing the state administration of Russia. By this time, nomadic hordes of Pechenegs appeared on its southern borders, who overwhelmed all other nomadic tribes and began to attack the border regions of Russia. They ravaged peaceful Slavic villages, plundered nearby towns and took people into slavery.

Another painful problem for Russia at that time was the Khazar Kaganate, which occupied the lands of the Black Sea region and the Lower and Middle Volga regions.

The international trade route "from the Varangians to the Greeks" passed through these territories, and the Khazars, blocking it, began to collect heavy duties from all merchant ships going through Russia from Northern Europe to Byzantium. Russian merchants also suffered.

The international trade route "from the Varangians to the Greeks" passed through these territories, and the Khazars, blocking it, began to collect heavy duties from all merchant ships going through Russia from Northern Europe to Byzantium. Russian merchants also suffered.

Thus, Prince Svyatoslav faced two main foreign policy tasks: to clear the trade routes up to Constantinople from extortions and to protect Russia from the raids of nomads - the Pechenegs and their allies. And the young prince set about solving the vital problems of his country.

Svyatoslav delivered the first blow to Khazaria. The Khazar Khaganate (650-969) was created by nomadic peoples who came to Europe from the Asian steppes during the Great Migration (4-6 centuries). Having seized vast territories in the regions of the Lower and Middle Volga regions, in the Crimea, Azov, Transcaucasia and North-West Kazakhstan, the Khazars conquered the local tribes and dictated their will to them.

Khazars

In 965, Russian troops invaded the border regions of Khazaria. Before that, Svyatoslav cleared the lands of the Slavs-Vyatichi from the numerous Khazar outposts and annexed them to Russia. Then, quickly dragging the boats from the Desna to the Oka, the Slavs descended along the Volga to the borders of the Kaganate and defeated the Volga Bulgars, which were dependent on the Khazars.

Further "The Tale of Bygone Years" says: "In the summer of 965 Svyatoslav went to the Khazars. Hearing, the Khazars went out to meet him with their prince Kagan and agreed to fight, and Svyatoslav the Khazars defeated in the battle. " The Rus managed to capture both capitals of the Khaganate - the cities of Itil and Semender, and also to clear Tmutarakan from the Khazars. The thunderbolt inflicted on the nomads echoed throughout Europe and became the end of the Khazar Kaganate.

In the same year 965, Svyatoslav also went to another Turkic state, which was formed on the territory of Eastern Europe during the Great Migration of Peoples - the Volga, or Silver, Bulgaria. Located in the 10th - 13th centuries on the territory of modern Tatarstan, Chuvashia, Ulyanovsk, Samara and Penza regions, Volga Bulgaria after the fall of the Khazar Kaganate became an independent state and began to claim part of the trade route "from the Varangians to the Greeks."

The capture of Semender by the Slavs

Having defeated the army of the Volga Bulgars, Svyatoslav forced them to conclude a peace treaty with Russia and thereby secured the movement of Russian merchant ships from Novgorod and Kiev to Byzantium. By this time, the glory of the victories of the Russian prince had reached Constantinople, and the Byzantine emperor Nicephorus Thomas decided to use Svyatoslav to fight the Bulgarian kingdom - the first European barbarian state of the 10th century, which won part of its lands from Byzantium and established its power on them. During its heyday, Bulgaria covered most of the Balkan Peninsula and had access to three seas.

Historians call this state the First Bulgarian Kingdom (681 - 1018). It was founded by the ancestors of the Bulgarians (Proto-Bulgarians), who united with the Slavic tribes of the Balkan Peninsula under the leadership of Khan Asparuh. The city of Pliska was considered the capital of Ancient Bulgaria, which in 893, after the adoption of Christianity by the Bulgarians, was renamed Preslav. Byzantium tried several times to regain the lands seized by the Bulgarians, but all attempts ended in failure.

Historians call this state the First Bulgarian Kingdom (681 - 1018). It was founded by the ancestors of the Bulgarians (Proto-Bulgarians), who united with the Slavic tribes of the Balkan Peninsula under the leadership of Khan Asparuh. The city of Pliska was considered the capital of Ancient Bulgaria, which in 893, after the adoption of Christianity by the Bulgarians, was renamed Preslav. Byzantium tried several times to regain the lands seized by the Bulgarians, but all attempts ended in failure.

By the middle of the 10th century, after several successful wars with its neighbors, the Bulgarian kingdoms strengthened, and the ambitions of its next ruler increased so much that he began to prepare for the seizure of Byzantium and its throne. In parallel, he sought recognition of the status of an empire for his kingdom. On this basis, in 966, a conflict broke out again between Constantinople and the Bulgarian kingdom.

Emperor Nicephorus Thomas sent a large embassy to Svyatoslav asking for help. The Greeks handed over to the Russian prince 15 centarii of gold and a request to "lead the Rus to the conquest of Bulgaria." The purpose of this appeal was the desire to resolve the territorial problems of Byzantium by someone else's hands, as well as to protect himself from the threat from Russia, since Prince Svyatoslav by this time had already begun to take an interest in the outlying provinces of Byzantium.

In the summer of 967, Russian troops led by Svyatoslav moved south. The Russian army was supported by Hungarian troops. Bulgaria, in turn, relied on the Yases and Kasogs, hostile to the Russians, as well as on the few Khazar tribes.

In the summer of 967, Russian troops led by Svyatoslav moved south. The Russian army was supported by Hungarian troops. Bulgaria, in turn, relied on the Yases and Kasogs, hostile to the Russians, as well as on the few Khazar tribes.

As chroniclers say, both sides fought to the death. Svyatoslav managed to defeat the Bulgarians and capture about eighty Bulgarian cities along the banks of the Danube.

Svyatoslav's trip to the Balkans was completed very quickly. True to his habit of lightning-fast hostilities, the prince, breaking through the Bulgarian outposts, defeated the army of the Bulgarian Tsar Peter in an open field. The enemy had to conclude a forced peace, according to which the lower course of the Danube with a very strong fortress city Pereyaslavets went to the Russians.

Having completed the conquest of Bulgaria, Svyatoslav decided to make the city of Pereyaslavets the capital of Russia, transferring all administrative structures here from Kiev. However, at that moment a messenger came from a distant homeland, who said that Kiev was besieged by the Pechenegs and Princess Olga was asking for help. Svyatoslav with a horse squad rushed to Kiev and, utterly defeating the Pechenegs, drove them away into the steppe. At this time, his mother died, and after the funeral Svyatoslav decided to return to the Balkans.

But before that it was necessary to organize the administration of Rus, and the prince put his sons on the kingdom: the eldest, Yaropolk, remained in Kiev; the middle one, Oleg, was sent by his father to the Drevlyansky land, and to Novgorod Svyatoslav, at the request of the Novgorodians themselves, gave his youngest son - Prince Vladimir, the future baptist of Russia.

But before that it was necessary to organize the administration of Rus, and the prince put his sons on the kingdom: the eldest, Yaropolk, remained in Kiev; the middle one, Oleg, was sent by his father to the Drevlyansky land, and to Novgorod Svyatoslav, at the request of the Novgorodians themselves, gave his youngest son - Prince Vladimir, the future baptist of Russia.

This decision of Svyatoslav, according to the Soviet historian B.A. Rybakov, marked the beginning of a difficult "specific period" in Russian history: for more than 500 years, Russian princes will divide the principalities between their brothers, children, nephews and grandchildren.

Only at the end of the XIV century. Dmitry Donskoy for the first time bequeaths to his son Vasily the Grand Duchy of Moscow as a single "fatherland". But specific skirmishes will persist even after the death of Dmitry Donskoy. For another century and a half, the Russian land will groan under the hooves of princely squads fighting with each other for the Great Kiev throne. Even in the 15th and 16th centuries, real "feudal wars" will continue to torment Moscow Russia: both Ivan III and his grandson Ivan IV the Terrible will fight against appanage princes, boyars.

In the meantime, having divided his possessions between his sons, Syatoslav began to prepare for a further struggle with Byzantium. Having collected in Russia replenishment for his army, he returned to Bulgaria. Explaining this decision of Svyatoslav, The Tale of Bygone Years gives us his words: “I don’t like to sit in Kiev, I want to live in Pereyaslavets on the Danube - because there is the middle of my land, all the benefits flow there: from the Greek land - gold, pavoloks, wine , various fruits, from Bohemia and Hungary, silver and horses, from Russia furs and wax, honey and slaves. "

Frightened by the successes of Svyatoslav, the Byzantine emperor Nikifor Foka urgently made peace with the Bulgarians and decided to consolidate it with a dynastic marriage. The bride had already arrived from Constantinople to Preslav when a coup d'etat took place in Byzantium: Nicephorus Phocas was killed, and John Tzimiskes sat on the Greek throne.

While the new Greek emperor hesitated to provide military assistance to the Bulgarians, they, frightened by Svyatoslav, entered into an alliance with him and then fought on his side. Tzimiskes tried to persuade the Russian prince to leave Bulgaria, promising him a rich tribute, but Svyatoslav was adamant: he decided to firmly settle on the Danube, thus expanding the territory of Ancient Russia.

While the new Greek emperor hesitated to provide military assistance to the Bulgarians, they, frightened by Svyatoslav, entered into an alliance with him and then fought on his side. Tzimiskes tried to persuade the Russian prince to leave Bulgaria, promising him a rich tribute, but Svyatoslav was adamant: he decided to firmly settle on the Danube, thus expanding the territory of Ancient Russia.