Slavs and Balts the time of existence. The origin of the Balts and the territory of their residence

Read also

If the Scythian-Sarmatians are far from the Slavs in language, does it mean that there is someone closer? You can try to find a solution to the mystery of the birth of Slavic tribes by finding their closest relatives by language.

We already know that the existence of a single Indo-European proto-language is beyond doubt. Approximately in the III millennium BC. NS. from this single proto-language, various groups of languages gradually began to form, which in turn, over time, were divided into new branches. Naturally, the carriers of these new kindred languages were different kindred ethnic groups (tribes, tribal unions, nationalities, etc.).

The studies of Soviet linguists, carried out in the 70-80s, led to the discovery of the fact of the formation of the Proto-Slavic language from the Baltic language array. There are a variety of judgments about the time at which the process of separation of the Proto-Slavic language from the Baltic took place (from the 15th century BC to the 6th century AD).

In 1983 the II conference "Balto-Slavic ethno-linguistic relations in the historical and areal plane" was held. It seems that this was the last such large-scale exchange of views of the then Soviet, including Baltic, historians and linguists on the origin of the Old Slavic language. The following conclusions can be drawn from the theses of this conference.

The geographic center of the Balts' settlement is the Vistula basin, and the territory occupied by the Balts stretched east, south, and west from this center. It is important that these territories included the Oka basin and the Upper and Middle Dnieper up to Pripyat. Balts lived in the north of Central Europe before the Wends and Celts! The mythology of the ancient Balts bore a clear Vedic connotation. Religion, the pantheon of gods almost coincided with the ancient Slavic ones. In a linguistic sense, the Baltic linguistic space was heterogeneous and was divided into two large groups - western and eastern, within which there were also dialects. The Baltic and Proto-Slavic languages contain signs of a great influence of the so-called "Italic" and "Iranian" languages.

An interesting mystery is the relationship of the Baltic and Slavic languages with the so-called Indo-European proto-language, which we, linguistics experts forgive me, will henceforth call the Proto-language. The logical scheme of the evolution of the Proto-Slavic language seems to be something like this:

Proto-language - Prabalt - + Italic + Scythian-Sarsmatian = Old Slavic.

This scheme does not reflect one important and mysterious detail: the Prabalt (aka “Balto-Slavic”) language, having formed from the Proto-language, did not stop contacts with it; both languages existed for a while at the same time! It turns out that the Pro-Baltic language is a contemporary of the Proto-language!

This contradicts the idea of the continuity of the Prabalt language from the Proto-language. One of the most authoritative experts on the problems of the Prabalt language V.N. Toporov put forward the assumption that "the Baltic area is a" reserve "of the ancient Indo-European speech". Moreover, THE PRABALTIC LANGUAGE IS AN ANCIENT LANGUAGE OF INDO-EUROPEANS!

Taken together with the data of anthropologists and archaeologists, this may mean that the Prabalts were representatives of the "catacomb" culture (beginning of the 2nd millennium BC).

Perhaps the ancient Slavs were some southeastern variety of the Prabalts? No. The Old Slavic language reveals continuity precisely from the western group of the Baltic languages (west of the Vistula!), And not from the neighboring eastern one.

Does this mean that the Slavs are the descendants of the ancient Balts?

Who are the Balts?

First of all, “Balts” is a scientific term for the related ancient peoples of the Southern Baltic, and not a self-name. Today the descendants of the Balts are represented by Latvians and Lithuanians. It is believed that the Lithuanian and Latvian tribes (Curonians, Letgola, Zimegola, Seli, Aukshtaity, Samogit, Skalva, Nadruv, Prussians, Yatvingians) were formed from more ancient Baltic tribal formations in the first centuries of the 1st millennium AD. But who were and where did these more ancient Balts live? Until recently, it was believed that the ancient Balts were the descendants of the carriers of the late nealytic cultures of polished battle axes and corded pottery (last quarter of the 3rd millennium BC). This opinion is contradicted by the results of research by anthropologists. Already in the Bronze Age, the ancient South Baltic tribes were absorbed by the "narrow-faced" Indo-Europeans who came from the south, who became the ancestors of the Balts. The Balts were engaged in primitive agriculture, hunting, fishing, lived in weakly fortified villages in log or clay-coated houses and semi-dugouts. Militarily, the Balts were inactive and rarely attracted the attention of Mediterranean writers.

It turns out that we have to return to the initial, autochthonous version of the origin of the Slavs. But then where does the Italic and Scythian-Sarmatian components of the Old Slavic language come from? Where do all those similarities with the Scythian-Sarmatians, which we talked about in the previous chapters, come from?

Yes, if we proceed from the initial goal at all costs to establish the Slavs as the most ancient and permanent population of Eastern Europe, or as the descendants of one of the tribes who settled on the land of the future Russia, then we have to bypass the numerous contradictions arising from anthropological, linguistic, archaeological and other the facts of the history of the territory on which the Slavs lived reliably only from the 6th century AD, and only in the 9th century the state of Rus was formed.

To try to more objectively answer the mysteries of the history of the emergence of the Slavs, let's try to look at the events that took place from the 5th millennium BC to the middle of the 1st millennium AD in a wider geographical space than the territory of Russia.

So, in the V-VI millennia BC. NS. in Asia Minor, Palestine, Egypt, India, the cities of the first reliably known civilizations are developing. At the same time, in the basin of the lower Danube, a "Vincha" ("Terterian") culture was formed, associated with the civilizations of Asia Minor. The peripheral part of this culture was the "Bug-Dniester", and later the "Trypillian" culture on the territory of the future Rus. The area from the Dnieper to the Urals at that time was inhabited by the tribes of early pastoralists who still spoke the same language. Together with the "Vinchan" farmers, these tribes were the ancestors of the modern Indo-European peoples.

At the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, from the Volga region to the Yenisei, right up to the western borders of the Mongoloid settlement, the “Yamnaya” (“Afanasyevskaya”) culture of nomadic pastoralists appears. By the second quarter of the III millennium BC. e., "yamniks" spread to the lands on which the Trypillians lived, and by the middle of the 3rd millennium BC pushed them westward. "Vinchans" in the III millennium BC gave rise to the civilizations of the Pelasgians and Minoans, and by the end of the III millennium BC - the Mycenaeans.

To save your time, I am omitting the further development of the ethnogenesis of European peoples in the III-II millennia BC.

It is more important for us that by the XII century BC the "Srubniks" - Cimmerians, who were part of the Aryans, or who were their descendants and successors in Asia, came to Europe. Judging by the distribution of the South Ural Bronze throughout Eastern and Northern Europe during this period, a vast territory was influenced by the Cimmerians. Many European peoples of late times owe the Aryan part of their blood to the Cimmerians. Having conquered many tribes in Europe, the Cimmerians brought them their own mythology, but they themselves changed, they adopted the local languages. Later, the Germans, who conquered the Gauls and Romans, spoke in a similar way in the Romance languages. After some time, the Cimmerians who conquered the Balts began to speak the Baltic dialects, merged with the conquered tribes. The Balts, who settled in Europe with the previous wave of peoples' migration from the Urals and the Volga, received from the Cimmerians the first portion of the "Iranian" component of their language and Aryan mythology.

Around the 8th century BC the Wends came from the south to the regions inhabited by the Western Prabalts. They brought a significant part of the "Italic" dialect into the language of the Prabalts, as well as the self-name - Wends. From the 8th to the 3rd century BC NS. waves of immigrants from the west passed one after another - representatives of the “Luzhitsa”, “Chornolis” and “Zarubenets” cultures pressed by the Celts, that is, the Etruscans, Wends and, possibly, the Western Balts. So the "western" Balts became "southern".

Both archaeologists and linguists distinguish two large tribal formations of the Balts on the territory of the future Rus: one - in the Oka basin, the other - in the Middle Dnieper region. It was them that the ancient writers could have in mind when speaking of neurons, disputes, aists, chives, villages, gelons and boudins. Where Herodotus placed Gelons, other sources at different times called Galindians, Goldscythians, Golunians, and Goliad. This means that the name of one of the Baltic tribes living in the Middle Dnieper region can be established with high probability.

So, the Balts lived on the Oka and in the Middle Dnieper. But these territories were under the rule of the Sarmatians (“between the Pevkinnians and the Fenns” according to Tacitus, that is, from the Danube to the lands of the Finno-Ugric peoples)! And the Peutinger tables assign these territories to the Wends and the Venedo-Sarmatians. This may mean that the southern Baltic tribes for a long time were in a single tribal union with the Scythian-Sarmatians. The Balts and Scythian-Sarmatians were united by a similar religion and an increasingly common culture. The power of the weapons of the Kshatriya warriors provided farmers, cattle breeders, fishermen and forest hunters from the Oka and the upper reaches of the Dnieper to the shores of the Black Sea and the foothills of the Caucasus with the possibility of peaceful labor and, as they would say today, confidence in the future.

At the end of the 3rd century, the Goths invaded Eastern Europe. They managed to conquer many tribes of the Balts and Finno-Ugrians, to seize a gigantic territory from the shores of the Baltic to the Volga and the Black Sea, including the Crimea.

The Scythian-Sarmatians fought for a long time and fiercely with the Goths, but still suffered a defeat, such a heavy defeat that had never happened in their history. It is not just that the memory of the events of this war remained in the "Lay of Igor's Campaign"!

If the Alans and Roksolans of the forest-steppe and steppe zone could escape from the Goths by retreating to the north and south, then the “royal Scythians” had nowhere to retreat from the Crimea. Most quickly they were completely destroyed.

The Gothic possessions divided the Scythian-Sarmatians into southern and northern parts. The southern Scythian-Sarmatians (Yases, Alans), to which the leader Bus, known from the Lay of Igor's Host, belonged, retreated to the North Caucasus and became vassals of the Goths. There was a monument-tombstone of Bus, installed by his widow and known to historians of the 19th century.

The northern ones were forced to go to the lands of the Balts and Finno-Ugrians (Ilmeri), who also suffered from the Goths. Here, apparently, a rapid merger of the Balts and Scythian-Sarmatians began, who were possessed by a common will and necessity - liberation from Gothic domination.

It is logical to assume that numerically, the majority of the new community were Balts, so the Sarmatians who fell into their midst soon began to speak South Balt with an admixture of the "Iranian" dialect - the Old Slavic language. For a long time the military-princely part of the new tribes was mainly of Scythian-Sarmatian origin.

The formation of the Slavic tribes took about 100 years during the life of 3-4 generations. The new ethnic community received a new self-name - "Slavs". Perhaps it was born from the phrase "sva-alans". "Alans" is apparently the common self-name of a part of the Sarmatians, although there was also a tribe of Alans proper (this phenomenon is not uncommon: later, among the Slavic tribes with different names, there was a tribe proper "Slovenes"). The word "sva" - among the Aryans, meant both glory and sacredness. In many Slavic languages, the sounds "l" and "v" easily pass into each other. And for the former Balts, this name, in the sound of "slo-vene", had its own meaning: the Veneti who knew the word, had a common language, as opposed to the "Germans" - the Goths.

The military confrontation with the Goths continued all this time. Probably, the struggle was carried out mainly by partisan methods, in conditions when cities and large villages, centers of arms craft, were captured or destroyed by the enemy. This affected both armaments (darts, light bows and shields woven from rods, lack of armor) and the military tactics of the Slavs (attacks from ambushes and cover, feigned retreats, luring into traps). But the very fact of the continuation of the struggle in such conditions suggests that the military traditions of the ancestors were preserved. It is difficult to imagine how long the struggle of the Slavs with the Goths would have lasted and how the struggle of the Slavs with the Goths could have ended, but hordes of the Huns burst into the Northern Black Sea region. The Slavs had to choose between a vassal alliance with the Huns against the Goths and a fight on two fronts.

The need to obey the Huns, who came to Europe as invaders, was probably met by the Slavs ambiguously and caused not only inter-tribal, but also intra-tribal disagreements. Some tribes split into two or even three parts, fighting on the side of the Huns or Goths, or against both. The Huns and Slavs defeated the Goths, but the steppe Crimea and the Northern Black Sea region remained with the Huns. Together with the Huns, the Slavs, whom the Byzantines also called the Scythians (according to the testimony of the Byzantine author Priscus), came to the Danube. Following the Goths retreating to the northwest, part of the Slavs went to the lands of the Venets, Balts-Lugians, Celts, who also became participants in the emergence of a new ethnic community. This is how the final basis and territory of the formation of the Slavic tribes was formed. In the 6th century, the Slavs appeared on the historical stage under their new name.

Linguistically, many scholars divide the Slavs of the 5th-6th centuries into three groups: Western - Wends, Southern - Sklavins, and Eastern - Antes.

However, Byzantine historians of that time see in the Sklavins and Antes not ethnic formations, but political tribal unions of the Slavs, located from Lake Balaton to the Vistula (Sklavina) and from the mouth of the Danube to the Dnieper and the Black Sea coast (Anta). The Antes were considered "the strongest of both tribes." It can be assumed that the existence of two unions of Slavic tribes known to the Byzantines is a consequence of inter-tribal and intra-tribal strife over the "Gothic-Hunnic" issue (as well as the presence of Slavic tribes with the same names distant from each other).

The Sklavins are probably those tribes (Millingi, Ezerites, North, Draguvites (Dregovichi?), Smolens, Sagudats, Velegesites (Volynians?), Vayunits, Berzites, Rinkhin, Krivichi (Krivichi?), Timochans and others), which in In the 5th century they were allies of the Huns, went with them to the west and settled north of the Danube. Large parts of the Krivichi, Smolens, Severians, Dregovichs, Volhynians, as well as the Dulebs, Tivertsy, Uchiha, Croats, Glade, Drevlyans, Vyatichi, Polochans, Buzhans and others who did not obey the Huns, but did not side with the Goths, made up the Ant alliance, who opposed the new Huns - the Avars. But in the north of the Sklavins, Western Slavs, little-known to the Byzantines, also lived - the Veneti: other parts of the once united tribes of the Polyans, Slovenes, as well as Serbs, Lyakhs, Mazurs, Mazovians, Czechs, Bodrici, Lyutichi, Pomorians, Radimichi - the descendants of those Slavs who once left parallel to the Hunnic invasion. From the beginning of the 8th century, probably under pressure from the Germans, the Western Slavs partially moved to the south (Serbs, Slovenes) and east (Slovenes, Radimichi).

Is there a time in history that can be considered the time of the absorption of the Baltic tribes by the Slavs, or the final merger of the southern Balts and Slavs? There is. This time is the VI-VII centuries, when, according to archaeologists, there was a completely peaceful and gradual settlement of the Baltic settlements by the Slavs. This was probably due to the return of a part of the Slavs to the homeland of their ancestors after the Avars seized the lands near the Danube by the Sklavins and Antes. Since that time, the “Wends” and Scythian-Sarmatians practically disappear from the sources, and the Slavs appear, and they operate exactly where the Scythian-Sarmatians and the disappeared Baltic tribes “were listed” until recently. According to V.V. Sedova "it is possible that the tribal boundaries of the early ancient Russian tribes reflect the peculiarities of the ethnic division of this territory before the arrival of the Slavs."

Thus, it turns out that the Slavs, having absorbed the blood of very many Indo-European tribes and nationalities, are still to a greater extent the descendants and spiritual heirs of the Balts and Scythian-Sarmatians. The ancestral home of the Indo-Aryans is Southwestern Siberia from the Southern Urals to the Balkhash and Yenisei. The ancestral home of the Slavs - the Middle Dnieper, Northern Black Sea region, Crimea.

This version explains why it is so difficult to find one single ascending line of the Slavic genealogy, and explains the archaeological confusion of Slavic antiquities. And yet - this is only one of the versions.

The search continues.

It's no secret that history and culture of the Baltic Slavs for centuries it has attracted great interest not only from German historians, who often do it more out of their professional duty, but no less from Russians. What is the reason for this continuing interest? To a large extent - the "Varangian question", but not only it. Not a single researcher or lover of Slavic antiquities can pass by the Baltic Slavs. Detailed descriptions in medieval German chronicles of brave, proud and strong people, with their own distinctive and unique culture, sometimes capture the imagination. Majestic pagan temples and rituals, many-headed idols and sacred islands, unceasing wars, ancient cities and unusual for the modern ear names of princes and gods - this list can be continued for a long time.

For the first time discovering the North-West Slavic culture, they seem to find themselves in a completely new, in many ways mysterious, world. But what exactly attracts him - does he seem familiar and familiar, or, on the contrary, is it just interesting because he is unique and does not look like other Slavs? Having studied the history of the Baltic Slavs for several years, as a personal opinion, I would choose both options at once. The Baltic Slavs, of course, were Slavs, the closest relatives of all other Slavs, but they also had a number of distinctive features. The history of the Baltic Slavs and the southern Baltic still keeps many secrets and one of the most poorly studied moments is the so-called early Slavic period - from the late era of the Great Nations Migration to the end of the 8th-9th centuries. Who were the mysterious tribes of the Rugs, Varins, Vandals, Lugians and others, called "Germans" by Roman authors, and when did the Slavic language appear here? In I tried to briefly give the available linguistic indications that before the Slavic language a certain other language, but not Germanic, but more similar to the Baltic, and the history of its study, was spread here. For greater clarity, it makes sense to give a few specific examples.

I. Baltic Substratum?

In my previous article, it was already mentioned that according to archeological data, in the south of the Baltic there is a continuity of material cultures of the Bronze, Iron and Roman periods. Despite the fact that traditionally this "pre-Slavic" culture is identified with the speakers of the ancient Germanic languages, this assumption contradicts the data of linguistics. Indeed, if the ancient Germanic population left the south of the Baltic a century or two before the arrival of the Slavs here, then where does such a decent layer of "pre-Slavic toponymy" come from? If the ancient Germans were assimilated by the Slavs, then why are there no borrowings of ancient Germanic toponymy (in the case of an attempt to isolate this, the situation becomes even more contradictory), did not they borrow the “Baltic” toponymy from them?

Moreover. During colonization and assimilation, not only the borrowing of the names of rivers and places, but also words from the language of the autochthonous population, the substrate, into the language of the colonialists, is inevitable. This always happens - where the Slavs had to closely contact the non-Slavic population, borrowings of words are known. You can point to borrowings from Turkic to South Slavic, from Iranian - to East Slavic, or from German - to West Slavic. By the 20th century, the vocabulary of the Kashubians living in the German environment was up to 10% borrowed from German. In turn, in the Saxon dialects of the regions of Germany surrounding Luzhitsa, linguists count up to several hundred not even borrowings, but Slavic relic words. If we assume that the Baltic Slavs assimilated the German-speaking population in the vast spaces between the Elbe and the Vistula, one would expect many borrowings from Old East Germanic in their language. However, this is not the case. If in the case of the Polabian Wends-Drevan this circumstance could still be explained by the poor fixation of vocabulary and phonetics, then in the case of another well-known North-Lehite language that has survived to this day Kashubian, it is much more difficult to explain this. It is worth emphasizing that we are not talking about borrowing into Kashubian from German or common Slavic borrowings from East German.

According to the concept of the East German substratum, it should have turned out that the Baltic Slavs assimilated the autochthonous population of the south of the Baltic after the division of the Proto-Slavic into branches. In other words, in order to prove the foreign-speaking population of the southern Baltic, assimilated by the Slavs, it is necessary to identify a unique layer of borrowings from the non-Slavic language, characteristic only for the Baltic and unknown among other Slavs. Due to the fact that practically no medieval monuments of the language of the Slavs of northern Germany and Poland have survived, except for a few mentions in chronicles written in a different linguistic environment, for the modern regions of Holstein, Mecklenburg and northwestern Poland, the study of toponymy plays the greatest role. The layer of these "pre-Slavic" names is quite extensive throughout the south of the Baltic and linguists usually associate it with "ancient European hydronymy". The results of the study of the Slavicization of the pre-Slavic hydronymy of Poland, cited by Yu. Udolph, may turn out to be very important in this regard.

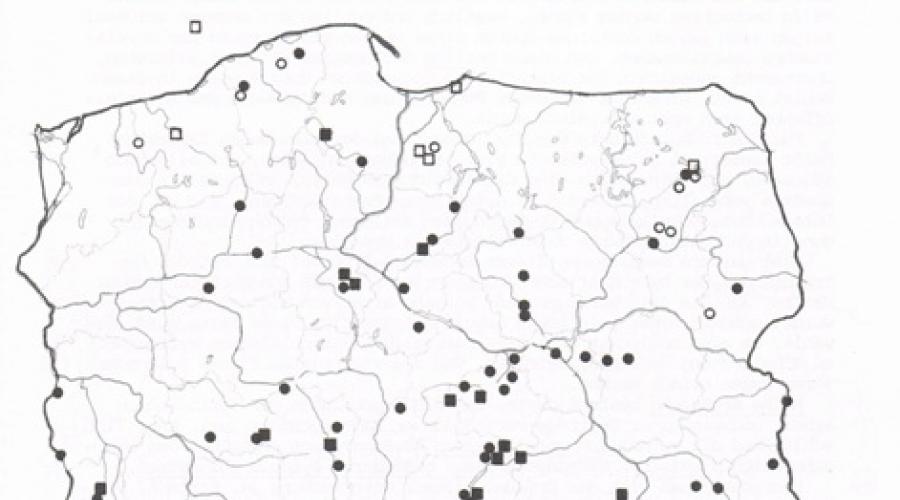

Slavic and pre-Slavic hydronyms of Poland according to Yu. Udolf, 1990

It turns out that the hydronymic situation in northern Poland is very different from its southern half. Pre-Slavic hydronymy is confirmed throughout the territory of this country, but significant differences are also noticeable. In the southern part of Poland, pre-Slavic hydronyms coexist with Slavic ones. In the north, it is exclusively pre-Slavic hydronymy. The circumstance is rather strange, since it is reliably known that since the era of at least the Great Migration of Nations, all these lands were already inhabited by speakers of the Slavic language proper, or various Slavic dialects. If we accept the presence of pre-Slavic hydronymy as a pointer to the pre-Slavic language or substrate, then this may indicate that part of the pre-Slavic population of southern Poland at some time left their lands, so that the speakers of the Slavic language proper, having settled these areas, gave the rivers new Slavic names. The line south of which Slavic hydronymics begins in Poland, on the whole, corresponds to the medieval tribal division, so that the zone of exclusively pre-Slavic hydronymy approximately corresponds to the settlement of the speakers of the Northern Lechite dialects. Simply put, the regions inhabited in the Middle Ages by various Baltic-Slavic tribes, better known under the collective name of the Pomorians, differ from the “Polish” ones by the absence of Slavic hydronymy proper.

In the eastern part of this exclusively "pre-Slavic" area, Mazov dialects began to prevail later, however, in the early Middle Ages, the Vistula River was still the border of the Pomorians and the Balto-speaking tribes. In the Old English translation of Orosius dating back to the 9th century, in the story of the traveler Wulfstan, the Vistula is indicated as the border of Windland (that is, the country of the Wends) and the Estonians. It is not known exactly how far south the Baltic dialects east of the Vistula extended to the south at that time. However, given that traces of Baltic settlements are also known west of the Vistula (see for example: Toporov V.N. New works on the traces of the stay of the Prussians to the west of the Vistula // Balto-Slavic studies, M., 1984 and further references), it can be assumed that part of this region in the early Middle Ages or during the era of the Great Migration of Peoples could speak Baltic. Another map by Yu. Udolph is no less indicative.

Slavicization of Indo-European hydronymy in Poland according to Yu. Udolph, 1990

The northern part of Poland, the southern coast of the Baltic, differs from other continental regions also in that only here are known pre-Slavic hydronyms that were not influenced by Slavic phonetics. Both circumstances bring the "Indo-European" hydronymics from the Pomorian region closer to the hydronyms from the Baltic lands. But if the fact that words did not undergo Slavicization for a long time in the lands inhabited by the Balts is quite understandable, then the Pomorian non-Slavic hydronyms seem interesting for the study of a possible pre-Slavic substrate. Two conclusions can be drawn from the maps above:

The Pomorian language was supposed to be closer to the neighboring West Baltic than the continental West Slavic dialects and to preserve some archaic Indo-European features or phonetics already forgotten in the Slavic languages proper;

Linguistic processes in the Slavic and Baltic regions of the southern Baltic proceeded in a similar way, which was reflected both in a wide layer of “Balto-Slavic” and “Baltic toponymy” and in phonetics. The "Slavization" (that is, the transition to the proper Slavic dialects) of the south of the Baltic should have begun later than in southern Poland.

It is extremely indicative that the data of the Slavicization of the phonetics of the hydronymics of northern Poland and the area of the "Baltic" toponymy of eastern Germany receive additional confirmation when compared with the differences in West Slavic languages and dialects that already existed in the Middle Ages. Linguistically and culturally, the West Slavic tribes of Germany and Poland are distinguished into two or three large groups, so that in the northern half of these lands there lived speakers of the North Lechite dialects, and in the southern half of the South Lehite and Lusatian-Serbian dialects. The southern border of "Baltic place names" in eastern Germany is Lower Lusatia, a region south of modern-day Berlin. Researchers of the Slavic toponymy of Germany E. Eichler and T. Witkowski ( Eichler E., Witkowski T. Das altpolabische Sprachgebiet unter Einschluß des Drawehnopolabischen // Slawen in Deutschland, Berlin, 1985) highlighted the approximate "border" of the distribution of Northern Lechite and Lusatian-Serbian dialects in Germany. With all the conventionality of this "border" and the possibility of small deviations to the north or south, it is worth noting that it very accurately coincides with the border of the Baltic toponymy.

Border of Northern Lechite and Lusatian-Serbian dialects in medieval Germany

In other words, the Northern Lechite dialects both on the territory of Germany and Poland in the Middle Ages became widespread in those territories where an extensive layer of "Baltic" toponymy is known. At the same time, the differences between North Lehite and other West Slavic languages are so great that in this case we are talking about an independent Proto-Slavic dialect, and not a branch or dialect of Lehite. The fact that at the same time the original Northern Lechite dialects also reveal a close connection with the Baltic in phonetics, and in some cases - much closer than with neighboring Slavic dialects - seems no longer a "strange coincidence" but a completely natural regularity (cf. . "Karva" and Baltic "karva", cow, or sev.-lech. "Guard" and Baltic. "Guard", etc.).

"Balt" toponymy and North-Lehite dialects

The above circumstances contradict the generally accepted concept of living here before the Slavs of the carriers of ancient Germanic dialects. If the Slavization of the South Baltic substratum took place for a long time and slowly, then the absence of Germanic place names and exclusive East Germanic borrowings into Kashubian can be called self-explanatory. In addition to the assumption of a possible East Germanic etymology of Gdansk, it turns out to be very tight with ancient Germanic toponymy here - at a time when many river names not only go back to the pre-Slavic language, but have also been preserved so well that they do not show any traces of the influence of Slavic phonetics. Yu. Udolph attributed the entire pre-Slavic hydronymy of Poland to the Old Indo-European language, before the division into separate branches, and pointed to the possible Germanic influence for the two names of the West Polish rivers Warta and Notech, however, here we were not talking about their own Germanic origin.

At the same time, in the Kashubian language, linguists see it possible to distinguish a layer of not just borrowings from the Baltic, but also relict Baltic words. You can point to the article "Pomorian-Baltic correspondences in vocabulary" by the famous researcher and expert of the Kashubian language F. Hinze ( Hinze F. Pomoranisch-baltische Entsprechungen im Wortschatz // Zeitschrift für Slavistik, 29, Heft 2, 1984) with the presentation of exclusive Baltic-Pomorian borrowings: 1 Pomorian-Old Prussian, 4 Pomorian-Lithuanian and 4 Pomorian-Latvian. At the same time, the observation made by the author in the conclusion deserves special attention:

“Among the examples given in both previous chapters, there may well be ancient borrowings from the Baltic and even Baltic relict words (for example, the Pomorian stabuna), however, it will often be difficult to prove this. Here I would like to give just one example, which testifies to the close connections between the Pomorian and Baltic speech elements. We are talking about the Pomorian word kuling - "curlew, sandpiper". Although this word by its root is etymologically and inseparable from its Slavic relatives (kul-ik), however, by morphological features, that is, by the suffix, it goes back to the Balto-Slavic proto-form * koulinga - “bird”. The closest Baltic analogue is lit. koulinga - "curlew", however, the Pomorian kuling should be a borrowing not from Lithuanian, but from Old Prussian, in favor of which Buga has already spoken out. Unfortunately, this word is not recorded in Old Prussian. In any case, we are talking about the ancient Baltic-Slavic borrowing "( Hinze F, 1984, S. 195).

The linguistic formulation of relict words is inevitably followed by a historical conclusion about the assimilation of the Baltic substrate by the Kashubians. Unfortunately, one gets the impression that in Poland, where they mainly studied Kashubian, this issue has moved from a purely historical to a political one. In her monograph on the Kashubian language, Hanna Popovska-Taborska ( Popowska-Taborska H. Szkice z kaszubszczynzny. Leksyka, Zabytki, Kontakty jezykowe, Gdansk, 1998) cites a bibliography of the issue, the opinions of various Polish historians "for" and "against" the Baltic substratum in the lands of the Kashubians, and criticizes F. Hinze, however, the very controversy that the Kashubians were Slavs, not Balts, seems more emotional than scientific , and the statement of the question is incorrect. The Slavism of the Kashubians is undoubted, but one should not rush from one extreme to another. There are many indications of a greater similarity of the culture and language of the Baltic Slavs with the Balts, unknown among other Slavs, and this circumstance deserves the closest attention.

II. Slavs with a "Baltic accent"?

In the above quote, F. Hinze drew attention to the presence of the –ing suffix in the Pomor word kuling, considering it to be an ancient borrowing. But it seems no less likely that in this case we can talk more about a relict word from a substrate language, since in the presence of a Slavic own sandpiper from the same root common to the Balts and Slavs, all grounds for actually "borrowing" are lost. Obviously, the assumption of borrowing arose from the researcher due to the unknown suffix -ing in Slavic. Perhaps, with a broader consideration of the issue, such word formation will not be so unique, but on the contrary, it may turn out to be characteristic of the Northern Lechite dialects that arose in the places of the longest preservation of the "pre-Slavic" language.

In Indo-European languages, the –ing suffix meant belonging to something and was most typical for Germanic and Baltic. Udolph notes the use of this suffix in the pre-Slavic place names of Poland (the preforms * Leut-ing-ia for the hydronym Lucaza, * Lüt-ing-ios for the toponym Lautensee and * L (o) up-ing-ia for Lupenze). The use of this suffix in the names of hydronyms later became widely known for the Baltic-speaking regions of Prussia (for example: Dobr-ing-e, Erl-ing, Ew-ing-e, Is-ing, Elb-ing) and Lithuania (for example: Del- ing-a, Dub-ing-a, Ned-ing-is). Also, the –ing suffix was widely used in the ethnonyms of the tribes of “ancient Germany” - one can recall the tribes listed by Tacitus, whose names contained such a suffix, or the Baltic jatv-ing-i, in the Old Russian pronunciation known as Yatvyagi. In the ethnonyms of the Baltic-Slavic tribes, the suffix –ing is known among the Polabs (polab-ing-i) and Smeldings (smeld-ing-i). Since a connection is found between both tribes, it makes sense to dwell on this point in more detail.

Smeldingi are first mentioned in the Frankish annals under the year 808. During the attack of the Danes and Viltsy on the kingdom of the Cheer, the two tribes that had previously obeyed the Cheer - the Smeldings and the Linons - rebelled and went over to the side of the Danes. Obviously, this required two circumstances:

The Smeldings were not initially “encouraged”, but were forced into submission by them;

One can assume direct contact between the Smeldings and the Danes in 808.

The latter is important for the localization of daredevil. It is reported that in 808, after the conquest of two regions of encouragement, Godfried went to the Elba. In response to this, Charlemagne sent to the Elbe, to help the cheers, troops led by his son, who fought here against the Smeldings and Linons. Thus, both tribes had to dwell somewhere near the Elbe, bordering on the one hand with the encouraged, and on the other with the Frankish empire. Einhard, describing the events of those years, reports only about the "Linonian war" of the Franks, but does not mention the daredevils. The reason, as we see it, is that the Smeldings managed to withstand in 808 - for the Franks this campaign ended unsuccessfully, so no details about it have survived. This is also confirmed by the Frankish annals - in the next 809 the king of the encouraging Drazhko sets off on a retaliatory campaign against the Viltsy and on the way back conquers the daredevils after the siege of their capital. In the annals of Moissac, the latter is recorded as Smeldinconoburg - a word containing the stem smeldin or smeldincon and the German word burg, meaning fortress.

Subsequently, the Smeldings are mentioned only once more, at the end of the 9th century by the Bavarian geographer, who reports that next to the Linaa tribe are the Bethenici, Smeldingon and Morizani tribes. The Bethenichi lived in the Pringnitz region at the confluence of the Elbe and Gavola, in the area of the city of Havelberg and are subsequently referred to by Helmold as Brizani. The Linons also lived on the Elbe, west of the Bethenichs - their capital was Lenzen. Who exactly the Bavarian geographer calls Morizani is not entirely clear, since two tribes with similar names are known at once by the proximity - the Morichans (Mortsani), who lived on the Elbe south of the Bethenichi, closer to Magdeburg, and the Murichans, who lived on Lake Müritz or Moritz, to the east of betenichi. However, in both cases, Morichans are neighbors of the Betenichi. Since the Linons lived on the southeastern border of the Obodrit kingdom, the place where the dwarves lived can be determined with sufficient accuracy - in order to meet all the criteria, they had to be the western neighbors of the Linons. The southeastern border of the Saxon Nordalbingia (that is, the southwestern border of the encouraging kingdom), the imperial letters and Adam of Bremen call the Delbend Forest, located between the river of the same name Delbenda (a tributary of the Elbe) and Hamburg. It was here, between the Delbend forest and Lenzen, that the dwarves were supposed to live.

Prospective area of settlement of the Smeldings

Mention about them mysteriously ceases at the end of the 9th century, although all their neighbors (linons, cheers, Viltsy, Morichans, Brizani) are often mentioned later. At the same time, starting from the middle of the 11th century, a new large tribe of Polabs “appeared” on the Elbe. The first mention of the Polabs goes back to the charter of the Emperor Henry in 1062 as the "region of Palobe". Obviously, in this case there was a banal slip of the tongue from Polabe. A little later, the polabingi are described by Adam of Bremen as one of the most powerful obodrit tribes, it is reported about the provinces subordinate to them. Helmold called them polabi, however, as the toponym once calls them "the province of the polabing". Thus, it becomes obvious that the ethnonym polabingi comes from the Slavic toponym Labe (polab-ing-i - "inhabitants of Polabe") and the suffix –ing is used in it as expected as an indication of belonging.

The capital of the Polabs was the city of Ratzeburg, which was located at the junction of the three provinces of encouragement - Wagria, the "land of the encouraged" and the Labe. The practice of setting up princely rates on the borders of the regions was quite typical for the Baltic Slavs - one can recall the city of Lyubitsa, which stands on the border of Vagria and the "land of the emboldened in a narrow sense" (practically - next to Ratzeburg) or the capital of the hijans, Kessin, which was located on the very border with the emboldened , on the Varnov river. However, the area of settlement of the Polabs, already based on the very meaning of the word, should have been located in the Elbe region, no matter how far from the Elbe their capital was located. The Polabings are mentioned simultaneously with the Linons, therefore, in the east, the border of their settlement could not be east of Lenzen. This means that the entire region, bounded in the northwest by Ratzeburg, in the northeast by Zverin (modern Schwerin), in the southwest by the Delbend forest, and in the southeast by the city of Lenzen, should be considered as a presumptive place for the settlement of the Polabs, so that in the eastern part of this area also includes the areas previously inhabited by smeldings.

Estimated area of settlement of the Polabs

Due to the fact that chronologically the Polabs begin to be mentioned later than the Smeldings and both tribes are never mentioned together, it can be assumed that the Labe by the 11th century became a collective name for a number of small regions and the tribes inhabiting them between the Obodrit and the Elba. Having been under the rule of the Encouraging kings at least from the beginning of the 9th century, in the 11th century these regions could have been united into a single province "Labe", ruled by the Prince of Encouragement from Ratzeburg. Thus, for two centuries the Smeldings simply “dissolved” in the “Polabs”, having not had their own self-government since 809, by the 11th century they were no longer perceived by their neighbors as a separate political force or tribe.

It seems all the more curious that the suffix -ing is found in the names of both tribes. It is worth paying attention to the name of smeldings - the most ancient of both forms. The linguists R. Trautmann and O.N. Trubachev explained the ethnonym Smeldings from the Slavic "Smolyan", however, Trubachev already admitted that methodologically such an etymology would be a stretch. The fact is that without the -ing suffix, the stem smeld- remains, and not smel- / smol-. At the root, there is another consonant, which is repeated with all mentions of smeldings in at least three independent sources, so to write off this fact as a "distortion" would be an escape from the problem. The words of Udolph and Kazemir come to mind that it would be impossible to explain dozens of toponyms and hydronyms based on Germanic or Slavic in neighboring Lower Saxony, and that such an explanation becomes possible only with the use of the Baltic. In my personal opinion, breeders are just such a case. Neither Slavic nor Germanic etymology is possible here without strong strains. The Slavic did not have the -ing suffix and it is difficult to explain why the neighboring Germans suddenly needed to transmit the word * smolani through this Germanic particle, at a time when dozens of other Slavic tribes in Germany were easily written by the Germans with the Slavic suffixes -ani, -ini.

More probable than the "Germanization" of Slavic phonetics, would be purely Germanic word formation, and smeld-ingi would mean "inhabitants of Smeld" in the language of the neighboring Saxons. The problem here is that the name of this hypothetical region Smeld is difficult to explain from Germanic or Slavic. At the same time, with the help of the Baltic, this word acquires a suitable meaning, so that neither semantics nor phonetics require any stretching. Unfortunately, linguists who compose etymological reference books, sometimes for huge regions, very rarely have a good idea of the places they describe. It can be assumed that they themselves have never been to most of them and are not thoroughly familiar with the history of each specific toponym. Their approach is simple: are the Smeldings a Slavic tribe? This means that we will look for etymology in Slavic. Are similar ethnonyms known in the Slavic world? Are Smolyans known in the Balkans? Wonderful, that means Smolyan on the Elbe too!

However, every place, every people, tribe and even a person has its own history, without taking into account which one can go down the wrong path. If the name of the Smelding tribe was a distortion of the Slavic "Smolyan", then the Smeldings should have been associated with the burning, clearing of forests by their neighbors. This was a very widespread type of activity in the Middle Ages, therefore, in order to "stand out" from the mass of others engaged in burning, the smildings probably had to do this more intensively than others. In other words, to live in some very wooded, rugged terrain, where a person had to win a place for himself to live near the forest. Wooded places are really known on the Elbe - it is enough to recall the Draven region, located on the other side of the Elbe, or neighboring with Vagria Golzatia - both names mean nothing more than “wooded areas”. Therefore, "Smolyans" would look quite natural against the background of neighboring trees and golzats - "in theory". “In practice,” everything turns out to be different. The lower course of the Elbe between Lenzen and Hamburg really stands out strongly from other neighboring regions, however, not at all on the basis of a “forest” character. This region is known for its sands. Already Adam of Bremen mentioned that the Elbe in the region of Saxony "becomes sandy". Obviously, exactly the lower course of the Elbe should have been meant, since its middle and upper course at the time of the chronicler were part of the marks, but not actually "historical Saxony", in the story about which he placed his remark. It is here, in the area of the city of Deemitz, between the villages with the speaking names Big and Small Schmölln (Gross Schmölln, Klein Schmölln), where the largest inland dune in Europe is located.

Sand dune on the Elbe near the village of Maly Schmölln

In strong winds, the sand scatters from here for many kilometers, making the entire surrounding area infertile and therefore one of the most sparsely populated in Mecklenburg. The historical name of this area is Grise Gegend (German for "gray area"). Due to the high content of sand, the soil here really takes on a gray color.

Land in the area of the town of Demitz

Geologists attribute the appearance of the Elbe sand dunes to the end of the last ice age, when sand layers of 20-40 m were brought to the river banks with melt water. accelerated the process of spreading sand. Even now, in the Demitz area, sand dunes reach many meters in height and are perfectly visible among the surrounding plains, undoubtedly being the most "striking" local landmark. Therefore, I would like to draw your attention to the fact that in the Baltic languages sand is called very similar words: "smilis" (lit.) or "smiltis" (lat.). In a word Smeltine the Balts designated large sand dunes (compare the name of the large sand dune on the Curonian Spit, Smeltine).

Due to this, the Baltic etymology in the case of the bastards would look convincing both from the point of view of semantics and from the point of view of phonetics, while having direct parallels in Baltic toponymy. There are also historical grounds for "non-Slavic" etymology. Most of the names of the rivers in the lower reaches of the Elbe are of pre-Slavic origin, and the sand dunes near Demitz and Boyzenburg are located exactly in the interfluve of three rivers with pre-Slavic names - Elbe, Elda and Delbenda. The latter can also become a clue in the question of interest to us. Here it can be noted that it does not have an intelligible Slavic etymology and the name of a tribe neighboring with the Smeldings - the Linons or Lins, who also lived in the area of concentration of pre-Slavic hydronymics and were not part of either the Union of Encouragement or the Union of Lyutichi (i.e., perhaps also former of some other origin). The name Delbend was first mentioned in the Frankish annals under the year 822:

By order of the emperor, the Saxons are building a kind of fortress beyond the Elbe, in a place called Delbend. And when the Slavs who had occupied it before were expelled from it, a Saxon garrison was placed in it against the attacks [of the Slavs].

A city or a fortress with this name is not later mentioned anywhere else, although according to the annals, the city remained with the Franks and became the location of the garrison. It seems likely that the archaeologist F. Lauks has suggested that the Delbend of the Frankish annals is the future Hamburg. The German fortress Gammaburg on the Lower Elbe began to gain importance in the first half of the 9th century. There are no reliable letters on the basis of it (the existing ones are recognized as fakes), and archaeologists define the lower layer of the Gammaburg fortress as Slavic and attribute it to the end of the VIII century. Thus, Hamburg really had the same fate as the city of Delbend - the German city was founded in the first half of the 9th century on the site of a Slavic settlement. The river Delbend itself, on which the city was previously searched, flows east of Hamburg and is one of the tributaries of the Elbe. However, the name of the city could not come from the river itself, but from the Delbend forest described by Adam of Bremen, located between the Delbend and Hamburg rivers. If Delbend is the name of a Slavic city, and after the transition to the Germans it was renamed Gammaburg, then it can be assumed that the name Delbend could be perceived by the Germans as alien. Considering that both the Baltic and the Germanic etymologies are assumed for the hydronym Delbendé as possible at the same time, this circumstance can be considered as an indirect argument in favor of the “Baltic version”.

A similar way could be the case in the case of daredevils. If the name of the entire sandy area between Delbend and Lenzen came from the pre-Slavic, Baltic designation of sand, then the –ing suffix, as a designation of belonging, would be exactly in its place in the ethnonym “inhabitants of [the region] Smeld”, “inhabitants of the sandy area”.

Another, more eastern tributary of the Elbe with the pre-Slavic name Elda, may also be associated with the long-term preservation of the pre-Slavic substratum. On this river is the city of Parhim, first mentioned in 1170 as Parhom. At the beginning of the 16th century, the Mecklenburg historian Nikolai Marshalk left the following message about this city: “Among their [Slavic] lands there are many cities, including Alistos, mentioned by Claudius Ptolemy, now Parhun, named after an idol whose image, cast from pure gold, as they still believe, is hidden somewhere nearby "( Mareschalci Nicolai Annalium Herulorum ac Vandalorum // Westphalen de E.J. Monumenta inedita rerum Germanicarum praecipue Cimbricarum et Megapolensium, Tomus I, 1739, S. 178).

Judging by the expression "still believe", the information transmitted by the Marshal about the origin of the name of the city on behalf of the Slavic pagan deity was based on the tradition or idea that existed in Mecklenburg back in his time. At the beginning of the 16th century, as Marshalk points out elsewhere, there was still a Slavic population in the south of Mecklenburg ( Ibid., S. 571). Similar reports about the traces and memory of Slavic paganism preserved here are, indeed, far from isolated. Including the Marshalk himself mentioned in his Rhymed Chronicle about the preservation of a certain crown of the idol of Radegast in the church of the city of Gadebusch at the same time. The connection between the Slavic past of the city in the popular memory with paganism resonates well with the discovery by archaeologists of the remains of a pagan temple in the accompanying Parkhim or replacing it at a certain stage of the fortress in Shartsin. This fortress was located just 3 km from Parhim and was a large, walled trading center on the southeastern border of the kingdom of the cheers. Among the many artifacts, many luxury goods, imports and trade indications have been found here, such as shackles for slaves, dozens of scales, and hundreds of weights ( Paddenberg D. Die Funde der jungslawischen Feuchtbodensiedlung von Parchim-Löddigsee, Kr. Parchim, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2012).

One of the structures found in the fortress is interpreted by archaeologists as a pagan temple, similar to the pagan temple in Gross Raden ( Keiling H. Eine wichtige slawische Marktsiedlung am ehemaligen Löddigsee bei Parchim // Archäologisches Freilichtmuseum Groß Raden, Museum für Ur- und Frügeschichte Schwerin, 1989). This practice of combining a place of worship and bargaining is well known from written sources. Helmold describes a large fish market on Rügen, where merchants were to make a donation to the Sventovit temple. From more distant examples, we can recall the descriptions of Ibn Fadlan about the Russians on the Volga, who started trading only after donating part of the goods to an anthropomorphic idol. At the same time, cult centers - significant temples and sanctuaries - show an amazing "vitality" in the people's memory and in the midst of historical transformations. New churches were built on the sites of old sanctuaries, and the idols themselves or parts of destroyed temples were often built into their walls. In other cases, the former sanctuaries, not without the help of church propaganda, which sought to “turn away” the flock from visiting them, were remembered as “damn”, “devilish” or just “bad” places.

Reconstruction of the Shartsin fortress and the pagan temple in the museum

Be that as it may, the form of the name of the pagan deity Parhun seems too similar to the name of the Baltic god of thunder Perkun to be an arbitrary "folk" invention. The location of Parhim on the southern border of the Obodrit lands, in close proximity to the concentration of pre-Slavic hydronymics (the city itself stands on the Elda River, whose name goes back to the pre-Slavic language) and the Smelding tribe, may be associated with the pre-Slavic Baltic substratum and indicate some of the resulting cultural or, rather, dialectal differences between the northern and southern obodrit lands.

Since the 16th century, the idea of the origin of the name Parhim from the name of the pagan god Parhun has been popular in Latin-language German works. After the Marshal in the 17th century, Bernard Latom, Konrad Dieterik and Abraham Frenzel wrote about him, who identified the Parkhim Parhun with the Prussian Perkunas and the Russian Perun. In the 18th century, Joachim von Westphalen also placed in his work the image of the Parkhim Parhun in the form of a statue standing on a pedestal, with one hand leaning on a bull standing behind it and holding a red-hot iron with lightning emanating from it in the other. The head of the Thunderer was surrounded by a halo in the form of a kind of petals, apparently symbolizing the sun's rays or fire, and at the pedestal there was a sheaf of ears and a goat. It is curious that even at the beginning of the last century, the German inhabitants of Parhim were very interested in the Slavic past of their city, and the image of the god Parhun, the patron saint of the city from the work of Westphalen, solemnly swept through the streets of Parhim at the celebration of the 700th anniversary of the city.

Parkun - god of thunder and patron saint of Parhim at the city's 700th anniversary celebration

III. Chrezpenians and the "Velet legend"

It was already briefly mentioned about the connection of the ethnonym Chrazpenyans with the toponyms and ethnonyms of the type “through + the name of the river” characteristic of the Balts. Simplified, the argumentation of the supporters of the "Balt" hypothesis boils down to the fact that ethnonyms of this type were characteristic of the Balto-speaking peoples and there are direct analogs (circispene), and the argumentation of the supporters of the "Slavic" version is that such word formation is theoretically possible and among the Slavs. The question does not seem simple, and both sides are certainly right in their own way. It seems to me that the map of ethnonyms of this type cited by A. Incomponent is in itself a sufficient basis to suspect a connection here. Since linguists very rarely use archeological and historical data in their research, it makes sense to fill this gap and check if there are any other differences in the culture and history of this region. But first you need to decide where to look.

Let it not seem strange, but the Chrazpenyan tribe itself will not play a role in this matter. The meaning of the ethnonym is quite definite and means “living across the [river] Pena”. Already in scholium 16 (17) to the chronicle of Adam of Bremen, it was reported that "the hijans and through-Penyans live on this side of the Pena River, and the Tollenzyans and Redaria - on the other side of this river."

The ethnonym “living across the Pena” was supposed to be an exo-ethnonym given to the Perepenians by their neighbors. Traditional thinking always puts itself in the "center" and no nation identifies itself in a secondary role, putting its neighbors first, does not "seem" to be someone else's neighbors. For those living north of Pena, the Chrazpenians should have been the Tollenzyans living on the other side of the river, and not themselves. Therefore, to search for other possible features of native speakers, the word formation of which shows close ties with the Balts, it is worth turning to the Tollenzyan and Redarii tribes. The capital of the Chrazpenians was the city of Demin, which stands at the confluence of the Pena and Tollenza rivers (this confluence was incorrectly called by Adam "the mouth"). The ethnonym Tollenzyan, repeating the name of the river, unequivocally says that it was they who were the direct neighbors of the Chrazpenians "across the Pena" and lived along the Tollense River. The latter takes its source in Lake Tollenz. Somewhere here, obviously, the lands of the redarians should have begun. Probably, all 4 tribes of the Khizans, Crespenians, Tollenzyans and Redarians were originally of the same origin, or they became close during the time of the great union of the Viltsy or Veletes, therefore, when examining the question of the Cherezpenians, it is impossible to ignore the “Velet legend”.

Resettlement of the tribes of the Khizans, Chezpenians, Tollenzyans and Redarians

The Viltsy were first mentioned in the Frankish annals in 789, during the campaign against them by Charlemagne. More detailed information about the Wilts is reported by the biographer of Charlemagne, Einhard:

After those disturbances were settled, a war began with the Slavs, whom we usually call the Viltsy, but in fact (that is, in their own dialect) they are called Velatab ...

A certain bay stretches from the western ocean to the East, the length of which is unknown, and the width does not exceed a hundred thousand steps, although in many places it is narrower. Many peoples live around it: the Danes, as well as the Sveons, whom we call Normans, own the northern coast and all its islands. On the east coast live Slavs, Estonians and various other peoples, among whom are the main velatabats, with whom Karl was at that time at war.

Both of Einhard's remarks seem to be very valuable, since they are reflected in other sources as well. The early medieval idea that the Slavs once had one "main" tribe with a single king, which later disintegrated, should definitely have come from the Slavs themselves and, obviously, have some kind of historical basis. The same "legend" is transmitted by Arabic sources completely unrelated to Einhard. Al-Bekri, who used for his description the not preserved story of the Jewish merchant Ibn Yakub who visited the south of the Baltic Sea, reported:

The Slavic countries stretch from the Syrian (Mediterranean) Sea to the ocean in the north ... They form different tribes. In ancient times, they were united by a single king, whom they called Maha. He was from a tribe called the velinbaba, and this tribe was notable among them.

Very similar to Al-Bekri and the message of another Arab source, Al-Masoudi:

The Slavs are from the descendants of Madai, the son of Yafet, the son of Nukh; all the tribes of the Slavs belong to it and adjoin it in their genealogies ... Their dwellings are in the north, from where they extend to the west. They are different tribes, between which there are wars, and they have kings. Some of them profess the Christian faith according to the Jacobite sense, while some do not have scripture, do not obey the laws; they are pagans and know nothing of the laws. Of these tribes, one had previously in ancient times power (over them), his king was called Majak, and the tribe itself was called Valinana.

There are various assumptions about which Slavic tribe corresponded to "velinbaba" and "velinana", however, it is usually not associated with the velet. Meanwhile, the similarity in all three descriptions is quite large: 1) phonetically similar name - velataba / velinbaba / velinana; 2) characterization as the most powerful Slavic tribe in antiquity; 3) the presence of a certain legendary ruler named Maha / Majak (another reading option - Mahak - brings both forms even closer together) in two of the three messages. In addition, it is not difficult to “find” the Slavic Velin tribe in the Middle Ages. The Chronicle of Adam of Bremen, so little analyzed on the subject of Slavic ethnonyms and simply rewritten without hesitation from the time of Helmold to the present day, it seems, can help find answers to many difficult questions.

Hijans and through-Penyans live even further, - wrote Adam - who are separated from the Tollenzyans and Redaries by the Pena River, and their city Demmin. Here is the border of the Hamburg parish. There are other Slavic tribes that live between Elbe and Oder, such as gavolians living along the river Havel, doksans, lyubushans, wilines, Stodorane and many others. The strongest among them are those who live in the middle of the redaria ... (Adam, 2-18)

I underlined the key words to make it clearer that Adam definitely did not know that many Baltic Slavic tribes had Germanic exo-ethnonyms and Slavic self-names. Gavolians and Stodorians were one tribe - German and Slavic versions of the same name. The name Doksan corresponds to the name of the Doksa River, located south of the Redaria. Lebushans were supposed to live in the vicinity of the town of Lebusch on the Audra. But other sources do not know the wilin. Particularly indicative in this regard are the letters of the Saxon kings, the Magdeburg and Havelberg bishoprics of the 10th century, listing the conquered Slavic provinces - all the lands between the Odra and the Elbe, to the north to Pena and not knowing the "Wilin provinces", in contrast to the provinces and tribes of the Redarians, Transpenians or Tollenzyans ... The similar name of the Slavs who lived in the south of the Baltic somewhere between the cheers and the Poles is also known from the chronicle of Vidukind of Corveysky, in the 69th chapter of the 3rd book, which tells how, after the destruction of Starigard, Vikhman “turned east, reappeared among the pagans and negotiated with the Slavs, whose name is Vuloini, so that they somehow involve Meshko in the war. " The Veletes were indeed hostile to Meshko and were geographically located just east of the encouraging ones, however, in this case, the Pomor tribe of the Volynians, as the prototype of Vuloini Vidukinda, would have been no less likely. Indirectly, this version is supported by other forms of writing this word in Vidukind's manuscripts: uuloun, uulouuini, and the popularity of Vidukindu veletov under the German form of the name Wilti. Therefore, here we will limit ourselves only to mentioning such a message, without involving it in the reconstruction of the “Velet legend”.

It can be assumed that the "Velins" of Adam, named by him among the Velet tribes, were not the name of a separate tribe, but the same ancient self-name of the Viltsy - the Velet. If both names were Slavic, then the meaning of both, obviously, had to be “great, big, huge, major”, which semantically and phonetically fits well with the Slavic legend about the “main tribe of Slavs” velatabi / velinbaba / velinan. At the same time, the hypothetical period of the "supremacy" of the Veletov over "all Slavs" historically could only have occurred until the 8th century. The premises of this period seem to be even more suitable during the time of the Great Migration of Nations and the moment of the separation of the Slavic language. In this case, the preservation of legends about a certain period of greatness of the Wilts in the epic of the Continental Germans also seems significant. The so-called Saga of Tidrek of Berne tells the story of King Wilkin.

There was a king named Vilkin, glorious for his victories and courage. By force and devastation, he took possession of the country that was called the country of the Wilkins, and now it is called Svitod and Gutaland, and the whole kingdom of the Swedish king, Scania, Skaland, Jutland, Vinland and all the kingdoms that belong to that. So far stretched the kingdom of Wilkin the king, as the country designated by his name. Such is the method of the story in this saga, that on behalf of the first leader his kingdom and the people ruled by him take the name. Thus, this kingdom was also called the country of the Wilkins on behalf of the king Vilkin, and the people of the Wilkinians, the people who live there - all this until the new people took dominion over that country, which is why the names change again.

Further, the saga tells about the devastation of the Polish (Pulinaland) lands and "all kingdoms to the sea" by King Wilkin. After which Vilkin defeats the Russian king Gertnit and imposes tribute on all his vast possessions - the Russian lands, the land of Austrikka, most of Hungary and Greece. In other words, in addition to the Scandinavian countries, Vilkin becomes the king of almost all lands inhabited by the Slavs since the era of the Great Migration of Peoples.

In the people who received their name from King Vilkin - that is, the Wilkins - the Germanic pronunciation of the Slavic Veletov tribe - Viltsy - is clearly recognizable. Similar legends about the origin of the name of the tribe on behalf of its legendary leader were indeed very widespread among the Slavs. Kozma Prazhsky in the XII century described the legend about the origin of Russians, Czechs and Poles (Poles) from the names of their legendary kings: brothers Rus, Chech and Lech. The legend about the origin of the names of the Radimichi and Vyatichi tribes from the names of their leaders Radim and Vyatko in the same century was recorded by Nestor in the Tale of Bygone Years.

Leaving aside the question of how such legends corresponded to reality and noting only the characteristic nature of such a tradition of explaining the names of tribes by the names of their legendary ancestors, we emphasize once again the obvious common features of the ideas of different peoples about the velet: 1) domination over the "Slavs, Estonians and other peoples" on the coast Baltics according to Frankish sources; 2) domination over all Slavs during the reign of one of their kings, according to Arab sources; 3) the possession of the Baltic Slavic lands (Vinland), the occupation of Poland, and "all land to the sea", including the Russian, Central European and Balkan lands, as well as the conquest of Jutland, Gotland and Scandinavia under King Wilkin, according to the continental Germanic epic. The legend about King Wilkin was also known in Scandinavia. In the VI book of the Acts of the Danes, in the story of the hero Starkater endowed with Thor with the power and body of giants, Saxon Grammar tells how, after Starkater's journey to Russia and Byzantium, the hero goes to Poland and defeats the noble warrior Vasse, “whom the Germans -other record as Wilcze. "

Since the Germanic epic about Tidrek dating back to the era of the Great Nations Migration already contains the “Velet legend” and the form of “wilka”, there is every reason to suspect a connection between this ethnonym and the Wilts mentioned earlier by the ancient authors. Such an initial form could well have passed in the Germanic languages into "wilzi" (however, in some sources, like the above-cited Vidukind, the Wiltsy are written exactly as Wilti), and in the Slavic languages into "veleta". By itself, the ethnonym might not mean initially “great”, but due to the subordination of this tribe at some time to neighboring Slavic tribes and phonetic similarity with the Slavic “great”, they begin to be understood in this sense. From this "folk etymology", in turn, in later times, an even simpler Slavic form "velina" with the same meaning "great" could have appeared. Since the legends place the period of the Velin domination in the time immediately before the division of the Slavic tribes and ascribe to them domination also over the Ests, comparing these data with the Balto-Slavic hypotheses of V.N. Toporov, it turns out that the Velines and should have been the very “last Balto-Slavic tribe” before the division of the Balto-Slavic into branches and the separation of Slavic dialects “on the periphery”. Opponents of the version of the existence of a single Balto-Slavic language and supporters of the temporary convergence of the Baltic and Slavic languages could also find confirmation of their views in the ancient epic, accepting the time of the Vilt's rule - the time of "rapprochement".

The name of the legendary ruler of “all Slavs” from the Velin tribe seems no less curious. Maha, Mahak / Majak - has many parallels in the ancient Indo-European languages, starting from the Sankr. máh - "great" (cf. the identical title of the supreme ruler of Mach in the ancient Indian tradition), Avestan maz- (cf. Ahura Mazda), Armenian mec, middle-upper German. "Mechel", middle lower German "mekel", old sak. "Mikel" - "big, great" (compare Old Scandal. Miklagard - "Great city"), to Latin magnus / maior / maximus and Greek μέγαζ. The German chroniclers also translate the name of the capital of the encouraged Michelenburg into Latin Magnopol, i.e. "great city". Perhaps the same ancient Indo-European root * meg'a- with the meaning “great” also goes back to the “strange” names of noble cheers - princes Niklot and Nako, priest Miko. In the 13th century, the Polish chronicler Kadlubek wrote in his chronicle a similar "tale" about the legendary ruler of the encouraged Mikkola or Miklon, from whose name the capital of the encouraged was named:

quod castrum quidam imperator, deuicto rege Slauorum nomine Mikkol, cuidam nobili viro de Dale [m] o, alias de Dalemburg, fertur donasse ipsum in comitm, Swerzyniensem specialem, quam idem imperator ibidem fundauelon. Iste etenim Mikkel castrum quoddam in palude circa villam, que Lubowo nominatur, prope Wysszemiriam edificauit, quod castrum Slaui olim Lubow nomine ville, Theutunici vero ab ipso Miklone Mikelborg nominabant. Vnde usque ad presens princeps, illius loci Mikelborg appellatur; latine vero Magnuspolensis nuncupatur, quasi ex latino et slawonico compositum, quia in slawonico pole, in latino campus dicitur

Kadlubek's messages need critical analysis, since, in addition to numerous early written and contemporary oral sources, they also contain a considerable amount of the chronicler's own fantasy. "Folk etymology" in his chronicle is a completely ordinary matter, they, as a rule, do not represent historical value. However, in this case, we can cautiously assume that the knowledge of the Slavic legend about a “great ruler” with a similar name, also recorded by Al-Bekri and Al-Masudi and included in the Germanic epic in newer, German form "Wilkin".

Thus, the name of the legendary ruler of the Velins, Makha, could simply be the "title" of the supreme ruler, who came from the "pre-Slavic language" and was preserved only in the early medieval Slavic epic and the names / titles of the Baltic-Slavic nobility. In this regard, it would be the same "pre-Slavic relic" as "pre-Slavic toponymy", while the very name of the tribe has already passed into the purely Slavic "veliny", and a little later, as its descendants diverge into different branches and the gradual loss of significance as a political force and the emergence of a new name "lutichi" for the union of four tribes, and completely went out of use.

Perhaps, for greater clarity, it is worth dividing the toponymy of the southern Baltic not into 3 (German - Slavic - pre-Slavic) layers, as it was done before, but into 4: German - Slavic - “Balto-Slavic / Baltic” - “Old Indo-European”. In view of the fact that the supporters of the "Baltic" etymologies were not able to deduce all pre-Slavic names from the Baltic, such a scheme at the moment would become the least controversial.

Returning from the “Velin legend” to the Chrazpenians and Tollensians, it is worth pointing out that it is the lands of the Tollensians and Redaries that stand out from the others in archaeological terms in two ways. In the area of the Tollenza River, which, according to linguists, has a pre-Slavic name, there is a relatively large continuity of the population between the Roman period, the era of the Great Migration of Nations and the early Slavic time (sukovo-Dzedzi ceramics). The early Slavs lived in the same settlements or in close proximity to settlements that had existed here for hundreds of years.

Settlement of the Tollenz region during the Laten period

Settlement of the Tollens region during the early Roman period

Settlement of the Tollens region in the late Roman period

Settlement of the Tollenz region during the era of the Great Nations Migration

Late Germanic and early Slavic finds in the Neubrandenburg district:

1 - the era of the Great Nations Migration; 2 - early Slavic ceramics of the Sukov type;

3 - the era of the Great Nations Migration and ceramics of the Sukov type; 4 - Late Germanic finds and ceramics of the Sukov type

Already the Frankish chronicles report a large number of veletes, and this fact is fully confirmed by archeology. The population density in the Tollenskoe Lake area is astounding. Only for the period before 1981, in these places, archaeologists identified 379 settlements of the late Slavic period, which existed simultaneously, which is approximately 10-15 settlements per 10-20 square kilometers. However, the lands on the southern coast of Tollenskoye and the neighboring Lipetsk Lake (the modern German name of the lake is Lips, but the earliest letters mention the Lipiz form) stand out strongly even in such a densely populated region. On the territory of 17 square kilometers, 29 Slavic settlements were identified here, that is, more than 3 settlements per two square kilometers. In the early Slavic period, the density was less, but still sufficient to look "very numerous" in the eyes of neighbors. Perhaps the “secret” of the population explosion is precisely in the fact that the old population of the Tollenza basin was already considerable in the 6th century, when a wave of “Jedzi bitches” was added to it. The same circumstance could also determine the linguistic peculiarity of the Tollenzyans, in some features closer to the Balts than the Slavs. The concentration of pre-Slavic place names in the Velet regions seems to be the largest in eastern Germany, especially if we take into account the region of Gavola. Was this the ancient population between the rivers Pena, Gavola, Elba and Odra the same legendary viltas, or were they the carriers of Sukovo-Dziedzica ceramics? Obviously, some questions cannot be answered.

In those days, there was a great movement in the eastern part of the Slavic land, where the Slavs waged an internal war among themselves. Theirs are four tribes, and they are called Lyutichi, or Viltsy; of these, the Hizans and the Cross-Pennians, as you know, live on the other side of the Pena, while the Redaria and Tollenzyans live on this side. A great dispute began between them about primacy in courage and power. For the Redaria and Tollenzyans wanted to dominate due to the fact that they have the most ancient city and the most famous temple in which the idol of Redegast is exhibited, and they only ascribed to themselves the sole right of primacy, because all Slavic peoples often visit them for the sake of [receiving] answers and annual sacrifices.

The name of the city-temple of the Wilts of Retra, as well as the name of the pagan god Radegast, put researchers in a difficult position. Titmar of Merseburg was the first to mention the city, calling it Ridegost, and the god who was worshiped in him - Svarozhich. This information is quite consistent with what we know about Slavic antiquities. The toponymy in -gast, like the identical place names "Radegast", is well known in the Slavic world, their origin is associated with the personal male name Radegast, i.e. with quite ordinary people, whose name, for one reason or another, was associated with a place or settlement. So for the name of the god Svarozhich, you can find direct parallels in the ancient Russian Svarog-Hephaestus and Svarozhich-fire.