Science methodology concept; structure and tasks of philosophical and scientific methodology. General concept of methodology

Read also

Bulletin of the Voronezh Institute of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia №4 / 2014

PHILOSOPHICAL SCIENCES

N.M. Morozov,

Doctor of Philosophy, Associate Professor

METHODOLOGY OF SCIENCE AS A SCIENCE ABOUT METHODS OF Cognition

METHODOLOGY OF SCIENCE AS A STUDY OF THE SCHOLASTIC

The article analyzes the problem of the content of the methodology of science as a doctrine of the methods of cognition. The research paper analyzes various aspects of methodology of science as a study of the scholastic attainments.

The problem of the content of the methodology of science has always raised many questions in the scientific community. An analysis of the literature on this issue allows us to state the fact that the methodology of science, as a rule, is considered in a narrow and broad sense. In a broad sense, the methodology of science has as its goal the analysis of the immediate subject of science, the structure of scientific knowledge, its dynamics, functioning, regularities, etc. science. In this sense, the methodology of science considers such important conceptual characteristics of science as the comprehension of its own being, its system, laws, categories, functions. Most scientists cite the following as the main problems it solves: the testability of scientific theories, the ratio of scientific theories and reality, the laws of the formation of scientific theories, the nature of scientific knowledge, the structure of scientific knowledge, the language of science, the ratio of scientific and natural languages, scientific style of speech, etc. This self-reflection of science testifies to the age

the role of scientific knowledge in the modern world, the right of scientific activity to exist as an independent one. In principle, one can agree with this understanding of the content of the methodology of science. But, given the extremely broad meaning of the concept itself, it would be necessary to concretize its status as, for example, "theoretical comprehension of theory", as "scientific comprehension of science."

In a narrow sense, the methodology of science is understood as the doctrine of the methods of cognition, methods of research, methods of scientific activity. With this approach, many problems find themselves on the periphery of the concept of "methodology of science" (the doctrine of categories and definitions in science, the doctrine of the subject of science, the doctrine of its system, laws, the construction of scientific research, etc.). By the way, many scientists believe that it is more expedient to use the concept of "methodology of science" in this sense, that is, as a teaching about methods, as a theory of methods. Why? It is known that in the classical sense in the history and philosophy of science, the methodology of science has always been interpreted as a doctrine of methods.

Methods, methodology, technique - concepts that are directly related not only

Philosophical Sciences

scientific, but also all organized human activity. And not just connected, but aimed at the development of various areas of human activity. There are many definitions of methods, their classifications:

"... a method is a generalized representation of the scheme of interaction between a subject and an object (subject)", "a model of activity";

"... a method is a system of rules and regulatory principles applied to solve a certain range of tasks, leading to the achievement of a given goal";

In philosophy, a method is called "a method of constructing and substantiating philosophical knowledge."

The definition of the method as such in the philosophical tradition belongs, as you know, to R. Descartes: “By method, I mean precise and simple rules, strict adherence to which always prevents the mistaken for true, and, without wasting mental energy, but gradually and continuously increasing knowledge contributes to the fact that the mind achieves true knowledge of everything that is available to it ... ".

The famous philosopher of modern times F. Bacon compared the method with a lamp illuminating the way for a traveler in the dark.

The heterogeneous, diverse nature of scientific activity predetermines the diversity of the methods used, which, in turn, constitutes the methodology of scientific activity. A technique is a mechanism for implementing methods. It is with the help of specific methods that the tasks of implementing scientific requests in the interests of science are solved. For example, the subjective method orients the researcher towards the study of personal, subjective forms of expression and existence of phenomena of reality. This method is actively used in humanitarian knowledge. So, letters, diaries, notes, questionnaires can serve as rich materials for scientific research. The source of the analyzed material, created by one subject, becomes the subject of study of another subject. The objective method of scientific research is aimed at studying external, material phenomena outside their relationship to the subject: analysis of works, scientific texts. By the way, all natural scientific methods are objective.

A modern researcher today actively uses the sociological method, when any phenomenon is viewed as a social, social phenomenon, social institution, a form of social activity.

One cannot but recall the classical empirical and theoretical methods, the distinction of which was made by Hegel in relation to aesthetics. The empirical method orients the scientist to

external, factual study of phenomena, their description. The opposite of the empirical in Hegel's theoretical method - the method of "entirely theoretical reflection." As a dialectician, Hegel deeply understood the unity of these methods, noting that philosophical research "must contain mediated two of the above extremes, since it combines metaphysical universality with the certainty of real features." The task of identifying general patterns of scientific activity orients the scientist towards the study of the general, necessary, essential, stable, and not a single, accidental, which is.

The logical and historical methods have not lost their relevance. These methods are directly related. The objective, real world (real scientific activity, for example) is the unity of the historical and the logical, the unity of its history and logic. In other words, in the real historical existence of scientific activity there is an objective logic of development. The history of scientific activity is a chronicle of the selfless labor of many generations of scientists, scientific schools, it is a chronicle of scientific discoveries, inventions, fundamentally new ideas. The logic of scientific activity is something common, natural both in the genesis and in the structure of the subject area of research. It is impossible to imagine reality only as chaos, disorder, chance. But it is also impossible to present reality as logos, order, necessity. Even the ancient Greeks drew attention to the unity of "chaos" and "logos", "immeasurable" and "measure", "disorder" and "order." Consideration of reality in the unity of opposite characteristics is the principle of dialectics. To understand the logic of scientific activity is one of the tasks of the methodology of science.

Methods of abstraction and idealization are also relevant in scientific activity. These methods are, according to scientists, "means of constructivization" of objects of knowledge. The purpose of the indicated methods is to obtain a direct object of scientific research. This object can be both abstract and idealized. But, naturally, they are not identical either in the nature of mental procedures or in the nature of the result obtained. Idealization as a method of constructing an idealized object of research occurs through some significant simplification of the object, mental exclusion or assumption, again, of some properties, relations, which in reality cannot be a priori. Thus, an idealized object arises, fixed in concepts, models, etc.

Bulletin of the Voronezh Institute of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia №4 / 2014

a stratum object acts as an abstraction of a process, genesis (development of a scientific idea), structure (content and form of scientific research). Abstraction of the process of scientific activity or the structure of scientific activity is based on the reflection of both their genetic and their structural aspects.

The methodology of science in the study of the laws of scientific activity produces objects both abstract and idealized (scientific works, style, metalanguage of science, the image of science, scientific values, etc.). These objects arise on the basis of empirical objects, which are real scientific phenomena (scientist, dissertation, monograph, article). As a result of abstraction and idealization, abstract and idealized scientific objects arise, which are fixed in the metalanguage, which makes it possible for them to enter the content of the methodology of science as “some ideal theoretical models of empirical objects”. In the history of the philosophy of science, scientific activity seems to be somewhat idealized. In fact, this is an activity in which deep disappointments, and accidents, and misunderstanding, and non-recognition, etc., are inherent.

As you can see, in philosophy, the importance of methods has always been highly valued. All the concepts of the authors mentioned in the article are united by the understanding of the method as a generalized model of scientific activity. It is with the help of specific methods that the problems of implementing scientific requests in the interests of science have always been and are being solved. It is known that science is a part of the spiritual life of society, a set of ideas, discoveries, inventions, theories. Each area of knowledge determines a different ratio of methods

knowledge and various forms, techniques, means of their implementation.

LITERATURE

Chapter I. GENERAL CONCEPTS ABOUT THE METHODOLOGY OF SCIENCE

I. Definitions of the methodology of science. The concept of a method in a narrow and broad sense.

In dictionaries and encyclopedias, methodology is defined as the doctrine of the method, which, in turn, means a set of techniques, methods, and regulatory principles of cognitive activity that provide it with the correct "path to the goal," that is, to objective knowledge. The appropriateness of the action of the set goal is that initial meaning of the method as a "path to the goal", which is often overshadowed by its understanding as a characteristic of the operational side of the action (method, technique, etc.).

This point of view is justified if we mean the method in the narrow sense of the word. At the same time, a broader understanding of the method can be found, for example, in the Philosophical Enzvklopedia, where it is defined as "a form of practical and theoretical assimilation of reality, proceeding from the laws of motion of the object under study." "The method is inseparably one with theory: any system of objective knowledge can become a method. In essence, a method is a theory itself certified by practice, addressed to the practice of research"; "Any law of science ... being cognized ... also acts as a principle, as a method of cognition." In this sense, one speaks of a method as a theory in action.

More definitions:

"A method is a type of relationship between elements of scientific knowledge (theories, laws, categories, etc.), historically formed or consciously formed, used in scientific cognition and practical transformation of reality as a source of obtaining new true knowledge relatively adequate to the objective laws (setting the boundaries of searches such, detecting the conditions of movement towards it, checking the degree of its truth), externally presented in the form of a system of instructions, techniques, methods, means of cognitive activity "(Boryaz).

"A method is a path of cognition, based on a certain set of previously obtained general knowledge (principles) ... Methodology is a teaching about the methods and principles of cognition. Since the method is associated with preliminary knowledge, the methodology, of course, is divided into two parts: the teaching about the initial foundations ( principles) knowledge and the doctrine of the methods and techniques of research based on these foundations. In the doctrine of the methods and techniques of research, the general aspects of particular methods of cognition that make up the general research methodology are considered "(Mostepanenko).

This definition removes the extremes of understanding methodology as an exclusively philosophical and worldview basis of cognition, or only as a set of technical means, techniques, research procedures. The second of the named points of view is characteristic of scientists and philosophers of positivist orientations, who deny the important role of the worldview in cognition.

However, behind such word usage is often not a fundamental denial of other meanings of the term, but only the use of a generic concept to designate one of the types or levels of methodological work. Thus, the sociologist generally deprives the methodological and procedural aspect of the organization of research of the methodological status and does not include it in any of the three "levels" of methodological analysis he has allocated. Therefore, it is necessary to distinguish between the peculiarities of word use and genuine differences in understanding the meaning and essence of methodological analysis among different authors. Most of them understand the term "method" somewhat narrower than the authors cited above propose to do, therefore they do not limit themselves to defining methodology as a teaching about the method of scientific knowledge.

The use of the term "methodology" in this text is close to the above interpretation. Speaking about methodology, we mean a special form of reflection, self-consciousness of science (a special kind of knowledge about scientific knowledge), which includes an analysis of the prerequisites and foundations of scientific knowledge (primarily philosophical and worldview), methods, ways of organizing cognitive activity; identification of external and internal determinants of the cognition process, its structure; a critical assessment of the knowledge obtained by science, the definition of historically specific boundaries of scientific knowledge with a given method of organizing it. With regard to a specific science, methodological analysis also includes answers to questions about the subject of science, including the criteria that delimit its subject from the subject of related sciences; about the main methods of this science, about the structure of its conceptual apparatus. The methodology also includes an analysis of the explanatory principles used in science, links with other sciences, a critical assessment of the results obtained, a general assessment of the level and prospects for the development of this science, and a number of other issues.

To discuss the types and levels of methodological analysis, it is first necessary to discuss the relationship between the concept of methodology and similar concepts of reflection, philosophy, worldview, science of science. It is precisely the insufficient differentiation of these concepts that often leads to the absence of meaningful progress in the development of problems in the methodology of science.

2. Methodology and reflection

Reflection is one of the types and even methods of cognition, the main feature of which is the focus on knowledge itself, on the process of obtaining it. We can say that reflection is the self-knowledge of a collective or individual subject. In the first case, reflection is carried out over objectified forms of knowledge and it can be conditionally called objective, and in the second case, over knowledge that is inseparable from the individual subject, and it is subjective in its form. An example of reflection over objectified knowledge is reflection over science, and an example of subjective reflection is self-observation as a method of an individual's cognition of his own mental processes.

He carried out a very meaningful analysis of the specifics of reflexive procedures and the nature of the knowledge obtained with their help. He substantiated the view of reflection as the unity of reflection and transformation of an object; its application in research leads to a creative alteration of the studied subject itself. “As a result of reflection, its object - the system of knowledge - is not only put into new relations, but the I is being rebuilt, that is, they become different from what it was before the process of reflection ... we are dealing in this case not with such an object that exists independently of cognition and consciousness, but with the cognitive reproduction of cognition and consciousness itself, that is, the appeal of cognition to itself. "

With regard to the self-knowledge of the individual, this thesis, which originates in the Hegelian understanding of reflection, seems obvious, but in the relations of objectified systems of knowledge, it has an unconditional heuristic value. In the latter case, there is not only going beyond the existing system of knowledge, but also transforming it by including the reflected knowledge into another context, into a new system of relations with other elements of knowledge. In this case, the most important mechanism for the increment of knowledge (how often psychology remains blind to this mechanism!) Is the transformation of some implicit knowledge (a set of prerequisites and assumptions that stand "behind the back" of certain formulations into explicit, directly formulated knowledge. does not remain without consequences for the knowledge itself, it leads to its clarification, often to the rejection of some, implicitly accepted premises. just misguided. "

It is extremely important to understand that whenever the framework of implicit, non-reflective knowledge is pushed back due to reflection, new implicit assumptions, implicitly present preconditions, inevitably arise. Consequently, any reflection at the same time generates new implicit knowledge, which serves as a good illustration of the dialectical nature of any act of cognition. This new implicit knowledge, in turn, can be reflected, etc. But in this case, a certain "semantic frame" is always needed, which plays the role of a means of reflection, but is not itself reflected. It is possible to comprehend it only with the help of a different semantic frame; which in the new context will remain unreflected. The limit of such movement is determined by those cognitive or practical tasks that need to be solved with the help of new knowledge.

According to the opinion, reflection is one of the most essential immanent features of science, as, indeed, of any rational action of an individual. It presupposes not just a reflection of reality in knowledge, but also a conscious control over the course and conditions of the cognition process.

indicates that the very birth of science is associated with the transition from pre-reflective representations of everyday consciousness to scientific concepts with the help of reflexive procedures. The selection of the empirical and theoretical stages of the development of science, justified by him, also includes as one of the criteria the degree of reflection, awareness of cognitive means. Further "progress of scientific knowledge consists in the ever greater overcoming of this inertia of ordinary non-reflective consciousness in relation to conceptual means."

believes that the growth of self-reflectiveness of scientific and theoretical thinking is associated with the complication of the means of cognitive activity, an increase in the number of links of intermediaries between the upper levels of the theory and its empirical basis, which leads to the emergence of "fundamentally new components in the system of scientific knowledge itself: theoretical reflection on the logical structure and cognitive the meaning of those conceptual systems that reflect objective reality. " Conceptually, these components in their developed form constitute the "body" of methodology as a special branch of human knowledge.

Reflection as a form of theoretical activity of a socially developed person, aimed at understanding their own actions and their laws, is characteristic not only of scientific activity. She was born and received the highest development in philosophical knowledge. And until now, despite the appearance of reflection within science itself, philosophy retains the prerogative of providing the upper levels of self-awareness of scientific activity.

Reflection on philosophical knowledge is apparently performed by philosophy itself, possessing in this sense a "self-reflective property".

notes that since the beginning of the XX century. a sharp expansion of the sphere of reflection over science began. A fundamentally new form of it has emerged - external, "nonspecific" reflection aimed at studying social conditions and the results of the cognition process, in particular, questions about the role of science in society and the responsibility of scientists for the results of their activities. As for the tendencies in the development of specific, intrascientific reflection, then, using terminology, he designates it as a movement from ontologism through gnosologism to methodologism. Ontologism is characterized by concentration on the relationship between an object and knowledge, in the latter only its objective content is distinguished. Cognition is viewed as a forward movement on the path to objective truth, and the purpose of reflection is to control the correctness of this movement, to identify the ultimate grounds in the object, the discovery of which gives the very only sought-after truth. This type of reflection is most characteristic of empiricism.

Under the influence of German classical philosophy, and the complication of the objects of specific sciences from the middle of the 19th century. the center of self-consciousness of science becomes the subject-object relation. Philosophers begin to look for the prerequisites and the last foundations of scientific knowledge in the forms of the organization of cognitive activity, which affect the content and logical organization of knowledge. This type of reflection, conventionally called gnoseologism, presupposes a plurality of foundations of knowledge and the relative nature of truth. The truth of knowledge here can be judged by its adequacy to the task, given to the method of mastering the object, and not by its proximity to some absolute and unique truth postulated by ontological reflection.

Methodologism, as the most characteristic type of reflection in modern science, is characterized by a focus on the means of cognition in the broadest sense of the word, which were listed above when discussing the terms methodology and method. At the same time, in applied and experimental research, as he notes, "the development of methodology leads to the fact that the analysis of means of knowledge gradually develops into their systematic production, and in some parts even into a kind of industry, since the forms of organization and the nature of scientific activity are becoming industrial." ... This is evidenced by the change, or rather the increased requirements for the scientific result itself, it must have a standardized "engineering" form, that is, it must be suitable for "docking", "linking" and use together with other results in the course of collective scientific activity.

Reflection at the level of methodology and in fundamental sciences acquires a constructive character, where the construction of an ideal object of science, a model of the studied reality, is taking place. An important consequence of the qualitative development of the self-consciousness of science is the emergence of general scientific concepts and disciplines that perform the function of reflecting on certain aspects of the cognitive process in special sciences.

3. Philosophy, worldview and methodology of science

Questions of the relationship between philosophy and science, their specificity are widely discussed in modern philosophical literature. In bourgeois philosophy, there are two tendencies in solving the problem of the relationship between philosophy and science. On the one hand, such irrationalist concepts as existentialism, philosophy of life, philosophical anthropology completely reject the importance of science for the formation of a philosophical worldview and even consider it as a force hostile to man. On the other hand, neopositivism (first of all scientism) recognizes proper scientific (i.e., specially scientific) cognition as the highest cultural value, capable of providing a person's orientation in the world without other forms of social consciousness. According to the second point of view, philosophy should discard worldview aspects and value approaches, while acting only as a function of the logic and methodology of science.

Specially and systematically analyzing the issue of the specifics of the philosophical and specifically scientific types of knowledge, he comes to the conclusion that the fundamental feature that distinguishes philosophical knowledge from all other types of knowledge is that philosophy is by specifically theoretical means (and this circumstance determines its deep commonality with science ) performs an ideological function.

It can be seen from the above statements that the main question that arises when considering the relationship between philosophy and science concerns the worldview aspects of philosophical and concrete scientific knowledge, since the latter also carries a high ideological load. For further analysis of the questions posed, we will briefly consider the relationship between the concepts of "philosophy" and "worldview".

The specificity of the worldview, in contrast to other systems of knowledge, is the attitude of a person to the world, that is, it includes not just knowledge about the world itself, and not just about a person regardless of the world. The worldview aspect can have any knowledge, including specific scientific knowledge. With each discovery constituting an epoch, even in the natural-historical field, wrote F. Engels, materialism must inevitably change its form.

Not only epoch-making discoveries, but also any facts of science, knowledge, including everyday knowledge and even knowledge - a delusion, for example, religious, can acquire and acquire world outlook significance. According to some authors, it is impossible to draw a line between knowledge that is worldview meaningless and knowledge that is worldview valuable. But any knowledge, including the facts of science, does not automatically become a fact of the worldview of an individual, a group of people or a class. To acquire this last quality, special work is needed, carried out - consciously or unconsciously - by the bearer of the worldview. Its essence is to project the result obtained by science onto your inner world, to give it not only objective, but also necessarily subjective meaning.

It goes without saying, however, that different knowledge differ in their potential ability to acquire worldview status. These sciences, due to their objectivity and direct influence on the way of life of people, are beginning to acquire an ever greater worldview force, despite the surge of interest in irrationalist concepts that occurs from time to time. To one degree or another, the explication of the worldview potential of scientific knowledge is carried out within the framework of science itself, but of all sciences, only philosophy is directly and properly a worldview science whose special task is to analyze the aggregate content of the worldview, reveal its general basis and present it in the form of a generalized logical system. In carrying out this task, it thereby acts as the basis of the worldview, as the most concentrated and generalized, theoretically formalized expression of the worldview.

Philosophy is a theoretical form of worldview, its general methodological core.

The above is the basis for a fairly clear solution to the problem of the relationship between philosophy and worldview. The worldview includes not only general philosophical, but also particular provisions, including those formulated by private sciences. Moreover, and this is especially important for a psychologist to emphasize, the worldview is based on the entire spiritual culture, absorbs, synthesizes in itself the reflection of all forms and aspects of social life through the prism of the main ideological question of a person's attitude to the world. Philosophy includes the highest level of the consciously reflected and theoretically formed worldview of the individual and social strata. At the same time, certain historically established forms of worldview may not have a philosophically formalized end.

Of course, in addition to philosophical and scientific knowledge, the political, legal, ethical, aesthetic and even religious experience of an individual, group, class contributes to the formation of a worldview. The worldview of an individual is determined (although not unambiguously, not automatically) by his belonging to a particular group. Therefore, the question of the progressiveness of a particular worldview, its historical perspective, its social essence always remains legitimate.

The worldview and its theoretical core - philosophy, performing a general methodological function in psychological research, make a great contribution to ensuring the objectivity and scientific nature of the results obtained in it.

Having considered briefly the question of the relationship between worldview and philosophy and defining philosophy as a theoretical form of worldview, it should be noted that philosophy also reveals the most general laws of the development of nature and society. At the same time, philosophy is based not only on science, but also on the entire totality of spiritual culture; it uses its own specific methods, which are not limited to special scientific methods of research (an example of such a method is reflection).

The fundamental difference between philosophy and any science is reduced to the difference between the very objects of private sciences and philosophy. Philosophy has as its specific object not just reality, mastered in other forms of consciousness, but types of orientation and awareness of one's place in reality; it correlates the type of orientation given by science and all other types of orientation. Therefore, philosophy is the self-consciousness of culture and, even more broadly, of the epoch as a whole, and not of science alone; that is why it is capable of setting guidelines for science itself. Philosophy as a theoretically formalized worldview is based on the entire totality of social practice, in which science is only one of the forms of crystallization of human experience.

It is precisely the assimilation by philosophy of the entire wealth of human experience that allows it to set guidelines for science itself and even often - to perform a meaningful heuristic function. It is not out of place to recall how often science "rediscovered" on concrete material those truths that were known to philosophy in the form of more abstract formulations centuries earlier, what role the knowledge of philosophy played in making scientific discoveries in the field of such an exact science as physics (A. Einstein, N . Boron).

It remains for us to consider the relationship between the concepts of philosophy, methodology and science of science. Sometimes you can come across the statement that methodology is the totality of philosophical questions of a given science. In a less categorical form, it sounds like this: "when they talk about methodology, then we are talking primarily about the methodological function and value of philosophy." Or: "the basis of the methodological understanding of knowledge ... is a philosophical approach." Indeed, being a form of reflection on scientific knowledge, the methodology of science is closely related to philosophy. It should be borne in mind, however, that in addition to the philosophical level, the methodological analysis of science includes a number of other levels or floors, namely, private scientific methodology.

As for the science of science, it is aimed at studying the organizational specifics of scientific activity and its institutions, a comprehensive study of scientific work, the study of activities for the production of scientific knowledge. This includes questions of the structural units of science (the disciplinary structure of science, the organization of interdisciplinary research), about the factors affecting the effectiveness of the work of scientific teams, about how to assess this efficiency and many other questions from the field of sociology and social psychology of science, scientometrics, etc. Important importance, especially in our country, is acquiring the planning and management of scientific activities in the organizational aspect.

A number of issues studied by science of science have an unconditional methodological status, but they have the character of so-called external, nonspecific reflection on science, relate mainly to socio-organizational problems and are not included in the subject of our analysis (sociology of science, psychology of science, psychology scientist, ethical problems of scientific activity).

4. The structure and functions of methodological knowledge

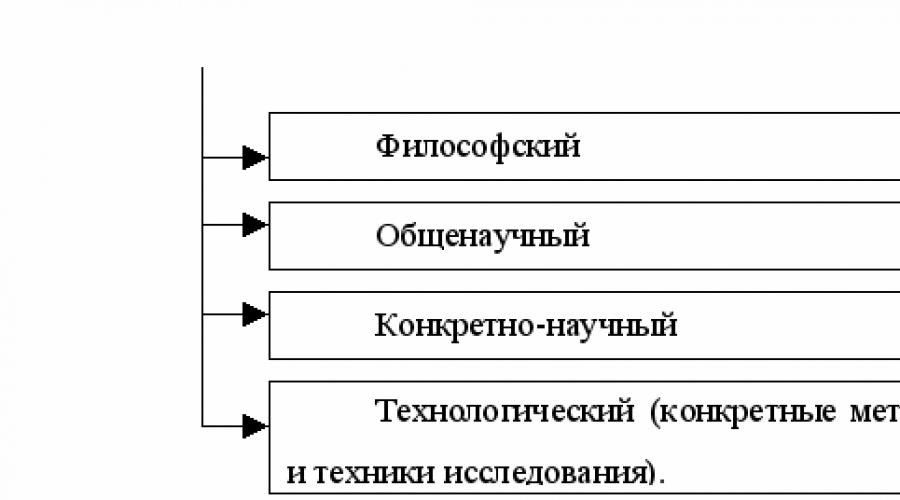

If we consider the structure of the methodology of science "vertically", then its following levels can be distinguished (161, p.86; 198, p.41-46): I) The level of philosophical methodology; 2) The level of general scientific principles and forms of research; 3) The level of specific scientific methodology; 4) The level of research methods and techniques. Some authors distinguish three levels. , for example, does not consider the research methodology and procedure as a level of methodological analysis. does not distinguish as an independent level the second of those listed above - the level of general scientific methodology.

Let's take a closer look at each of the highlighted levels. Philosophical methodology has the form of philosophical knowledge, obtained through the methods of philosophy itself, applied to the analysis of the process of scientific knowledge. The development of this level of methodology is carried out, as a rule, by professional philosophers. In his opinion, philosophy plays a double methodological role: “firstly, it carries out constructive criticism of scientific knowledge from the point of view of the conditions and boundaries of its application, the adequacy of its methodological foundation and general tendencies of its development. Secondly, philosophy gives a worldview interpretation of the results of science - in including methodological results - from the point of view of a particular picture of the world. "

The level of general scientific principles and forms of research was widely developed in the XX century. and this fact predetermined the separation of methodological research into an independent area of modern scientific knowledge. It includes: I) meaningful general scientific concepts, such as theoretical cybernetics as a science of control, the concept of the noosphere, 2) universal conceptual systems: tectology, general theory of systems by L. von Bertalanffy, 3) methodological or logical-methodological concepts proper - structuralism in linguistics and ethnography, structural and functional analysis in sociology, systems analysis, logical analysis, etc. - they perform the function of logical organization and formalization of special scientific content. A number of branches of mathematics also belong to the concepts of this type.

The general scientific nature of the concepts of this level of methodological analysis reflects their interdisciplinary nature, i.e., they are relatively indifferent to specific types of subject content, being aimed at highlighting the general features of the process of scientific cognition in its developed forms. This is precisely their methodological function in relation to concrete scientific knowledge.

The next level, the level of specific scientific methodology, is applicable to a limited class of objects and cognitive situations specific to a given area of knowledge. Usually, the recommendations that follow from it are of a pronounced disciplinary nature. The development of this level of methodological analysis is carried out both by the methodologists of science and theorists of the corresponding fields of knowledge (the latter, apparently, occurs more often). It can be said that at this level (sometimes called a private or special methodology), a certain way of knowing is adapted for a narrower field of knowledge. But this "adaptation" is by no means mechanical and is carried out not only due to the movement "from top to bottom", the movement must also come from the very subject of this science.

As a rule, philosophical and methodological principles do not directly correlate with the principles formulated at the level of special scientific methodology, they are first refracted, concretized at the level of general scientific principles and concepts.

The level of research methodology and technique is most closely related to research practice. It is associated, for example, with a description of methods, specific techniques for obtaining relevant information, requirements for the process of collecting empirical data, including conducting an experiment and methods for processing experimental data, accounting for errors. The regulations and recommendations of this level are most closely related to the specifics of the object under study and the specific tasks of the research, that is, methodological knowledge is the most specialized here. It is designed to ensure the uniformity and reliability of the initial data subject to theoretical comprehension and interpretation at the level of private scientific theories.

One of the important functions of differentiating the levels of methodological knowledge is to overcome two kinds of errors: I) reassessment of the measure of the community of knowledge of lower levels; an attempt to give them a philosophical and worldview sound (often there is a philosophical interpretation of the methodology of structuralism, the systems approach and other general scientific concepts); 2) direct transfer of provisions and patterns formulated at a higher level of generalizations without refraction, concretizing them on the material of particular areas (knowledge); For example, sometimes a conclusion is made about the specific paths of development of an object based on the application of the law of negation of negation to it, etc.

In addition to the differentiation of methodological knowledge by levels, the process of its consolidation on substantive grounds around the dominant methodological principles and even ideological attitudes is becoming more and more pronounced. This process leads to the formation of more or less pronounced methodological approaches and even methodological theories. There are special methodological orientations behind them. Many of them are built on a dichotomous principle and oppose each other (dialectical and metaphysical, analytical and synthetic, atomistic and holistic (holistic), qualitative and quantitative, energetic and informational, algorithmic and heuristic).

The concept of an approach is applicable to different levels of methodological analysis, but most often such approaches cover the two upper levels - philosophical and general scientific methodology. Therefore, in order for them to perform constructive functions in the special sciences, it is necessary to "melt" these approaches so that they cease to be external in relation to a particular discipline, but are immanently linked to its subject and the system of concepts that has developed in it. The mere fact of progressiveness and obvious usefulness of one or another approach does not guarantee the success of its application. If private science is not prepared "from below" to apply, for example, a systems approach, then, figuratively speaking, there is no "engagement" between the material of private science and the conceptual apparatus of this approach, and its simple imposition "from above" does not provide meaningful advancement.

This or that approach is not always carried out in an explicit and reflective form. Most of the approaches formulated in modern methodology were the result of retrospective selection and post factum realization of the principle that was implemented in the most successful concrete scientific studies. Along with this, there are cases of direct transfer of methodological approaches and scientific categories from one science to another. For example, the concept of a field in Gestalt psychology, including K. Levin's field theory, bear clear traces of the physical field theory.

The structural organization of methodological knowledge is directly related to the functions that it performs in the process of scientific cognition. Reflection on the process of scientific cognition is not an absolutely necessary component of it. The bulk of knowledge is applied automatically, without special thinking about their truth, their correspondence to the object. Otherwise, the process of cognition would be generally impossible, because each time it went into "bad" infinity. But in the development of each science there are periods when the system of knowledge that has developed in it does not ensure the receipt of results adequate to new tasks. The main signal of the need for a methodological analysis of the knowledge system is, in the opinion, the emergence of various paradoxes, the main of which is the contradiction between theoretical predictions and actually obtained empirical data.

The above provision refers to situations where reflection is needed on the categorical structure and explanatory principles of the whole science, that is, on a complex and objectified system of knowledge. But cognitive situations of a smaller scale may also require reflection - the failure of one particular theory or another, the impossibility of solving a new problem with the existing methods, and finally, the failure of attempts to give a solution to an actual applied problem. If we draw an analogy with the processes of different levels of control of human activity, we can say that scientific reflection of one level or another, as well as a person's awareness of his own actions, is required where the existing automatisms do not provide the necessary results and need to be restructured or supplemented.

Reflection and awareness are needed when the task is to build new scientific knowledge or form a fundamentally new behavioral act.

How can methodology help here, what are its functions in the process of concrete scientific cognition? Analyzing the various answers to this question, one can encounter both underestimation and overestimation of the role of methodology. Underestimation of its role is associated with narrow empirical tendencies that ignore its philosophical and ideological basis. These tendencies are characteristic of positivist-oriented approaches. But even here, in the newest versions of the "post-positivist" philosophy of science, there are shifts in the direction of recognizing the importance of philosophy and worldview for scientific research. The growth of interest in methodological knowledge and an increase in its role in modern science is a completely objective and natural process, which is based on such reasons as the complication of the tasks of science, the emergence of new organizational forms of scientific activity, an increase in the number of people involved in this activity, and an increase in the cost of science. , complication of the means used (on the direct nature of the process of obtaining scientific knowledge). sees one of the main reasons for the natural growth of "demand for methodology" precisely in the transformation of scientific activities into a mass profession, in methodology they begin to look for a factor that provides heuristic compensation - the replenishment of the productive capabilities of the average individual.

At the same time, a naive idea is often formed that everything in science comes down to finding suitable methods and procedures, the use of which will automatically ensure the receipt of a significant scientific result. Indeed, it is often necessary to find an adequate method to solve a problem, but it is impossible to do this, especially when it comes to a new method, only by moving "from above". It is becoming more and more clear that methodology by itself cannot solve meaningful scientific problems. Insufficient awareness of this fact gives rise to a "consumer" attitude to methodology as a set of recipes that are easy enough to learn and apply in the practice of scientific research. This is precisely where the danger of overestimating the role of methodology lies, which in turn, according to the law of the pendulum, can lead to its imaginary discrediting and, as a consequence, to underestimating its significance. The use of methodological principles is a purely creative process. The history of science shows that knowledge usually remains indifferent to methodological assistance imposed on it from the outside, especially in cases when this latter is offered in the form of detailed regulations. Therefore, a new conceptual framework can and does arise not as a result of a methodological reform carried out by someone from above, but as a product of internal processes taking place in science itself. As for methodological research in the special sense of the word, at best they can act as catalysts for these processes, intensifying the self-consciousness of science, but in no way substituting for it.

So, the first can be the function of catalyzing, stimulating the process of cognition as one of the main functions of methodological analysis. Closely related to it are such functions as problematization and critical comprehension of ideas functioning in culture, the formation of a scientist's creative personality by expanding his horizons, and fostering a culture of thinking.

The second function of the methodology is associated with the organization and structuring of scientific knowledge as a whole through its integration and synthesis, through the development of general scientific means and forms of cognition - general scientific concepts, categories, methods, approaches, as well as by highlighting common philosophical and worldview principles of cognition.

One of the consequences of the reflection of the methods of a particular science is the possibility of their transfer and use in other sciences, which allows the methodology, under certain conditions, to carry out a direct heuristic function.

A certain role is played by methodology in developing a strategy for the development of science, assessing the prospects of a particular scientific direction, especially when planning complex research, substantiating target programs. We can say that the methodology here acts as a kind of "prediction", which should indicate the most probable path to success, anticipating the result that will be obtained in the future. The main place in this substantiation is occupied by the characterization of the methods and ways of moving towards the goal, their compliance with the general requirements that have developed not only in science, but also in society at the current moment.

An important function of methodology (its philosophical level) is the worldview interpretation of the results of science from the point of view of a particular picture of the world.

The listed functions can be attributed to the functions of a methodology of a predominantly descriptive type, that is, having the form of a retrospective description of already carried out processes of scientific cognition. Even when we make the choice and justification of the direction of scientific research, trying to anticipate future results, we rely on the reflection of the previously traversed path to knowledge in the hope of choosing the optimal path. Normative methodological knowledge, which includes positive recommendations and rules for the implementation of scientific activities, has a fundamentally different, constructive character.

Normative methodological knowledge has the form of prescriptions and norms, and fulfills, according to, three main functions: ensures the correct statement of the problem both from the point of view of its content and form; provides certain means for solving already set tasks (intellectual technique of scientific activity); improves the organizational side of research.

As can be seen from the above definitions, the normative methodology is more closely related to the formal-organizational side of research activity, and the descriptive methodology is aimed at revealing the initial foundations and prerequisites of scientific knowledge, which, of course, always have a pronounced meaningful aspect.

Let's consider some methodological norms and regulations concerning the process of scientific cognition, as well as the different role of methodology at different stages of scientific activity.

For the analysis of scientific activity in the relevant sections of the methodology, a number of special concepts have been introduced and developed. The most general of them is the concept of a cognitive situation, which includes cognitive difficulty (the gap between the problem formulated in science and the means available in science), the subject of research, product requirements, as well as the means of organizing and implementing scientific research. The concept of the subject of research used here presupposes its differentiation from the concept of the object of research.

Subject of study is one of the central categories of methodological analysis. The origin and development of science is associated with the formation and change of the subject of science. A radical change in the subject of research leads to a revolution in science itself. The subject of research includes the object of study, the research task, the system of methodological tools and the sequence of their application. The subjects of research can be of varying degrees of generality, the most ambitious is the subject of this science as a whole, which performs a methodological function in relation to the subject of private research.

The concept of the object of study also requires clarification - it is not just some part of external reality that can be directly pointed to. In order to turn an object as a directly observable reality into an object of science, it is required to identify stable and necessary connections in this area of phenomena and fix them in the system of scientific abstractions, as well as to separate the content of the object, independent of the cognizing subject, from the form of reflection of this content. The process of constructing an object of scientific research is impossible without the emergence of a special cognitive task, a scientific problem.

The means of research include the fundamental concepts of science, with the help of which the object of research is dismembered and the problem is formulated, the principles and methods of studying the object, the means of obtaining empirical data, including technical means.

One and the same object can be included in the subject of several different studies and even different sciences. Completely different subjects in the study of man are built by such sciences as anthropology, sociology, psychology, physiology, ergonomics. Therefore, the concept of the subject of research is opposed not to an object, but to an empirical area - a set of scientific facts and descriptions on which the subject of research unfolds.

Based on this division of scientific knowledge, it is possible to outline the successive stages of the research movement, opening through the prism of normative and methodological analysis. As such stages are distinguished: the statement of the problem, the construction and substantiation of the subject of research, the construction of the theory and verification of the results obtained.

It is important to note that the formulation of the problem is based not only on the detection of the incompleteness of the available knowledge, but also on some "prediction" about the way to overcome this incompleteness. It is critical reflection that leads to the detection of gaps in the system of knowledge or the falsity of its implicit premises that play the leading role here. The work itself on the formulation of the problem is of a fundamentally methodological nature, regardless of whether the researcher deliberately relies on certain methodological provisions or they determine the course of his thoughts in an implicit way.

The work on the construction and substantiation of the subject of research is also primarily methodological, during which the problem is developed, it is included in the system of existing knowledge. It is here that the methodology merges with the content side of the cognition process. The methodology at this stage performs rather a constructive rather than a critical function, correcting the work of the researcher. At the stage of constructing the subject of research, new concepts, methods of data processing and other means are most often introduced, suitable for solving the problem.

At the stages of building a private scientific theory and checking the results obtained, the main semantic load falls on the movement in the subject content. From this it is clear that with the help of methodology in itself it is impossible to solve any particular scientific problem and it is impossible to construct the subject content of any specific area. For the successful use of the achievements of methodological thought, it is necessary to combine the creative movement "from top to bottom" and "from bottom to top".

The methodology itself is built and enriched not through the construction of speculative schemes, it grows out of the generalization of the gains achieved through movement in the subject content when analyzing a particular area of reality.

Any successful implementation of the methodological principle in specific scientific research is not only a contribution to this science, but also to methodology, since this implementation does not remain without consequences for the knowledge that was taken as a prerequisite, a research method. The latter are not only confirmed, but also enriched, supplemented every time they begin a new life, being embodied in the material of another subject area.

5. Methodology of science and psychology

Everything that has been said above about the methodology of science and its functions in private scientific research is also true in relation to psychology. However, any private science has its own specific, only inherent aspects of relations with the science of method, ties its own unique knots of methodological problems. This specificity is determined by the object of a given science and its complexity, the level of development of science, its current state (the presence of gaps in theory or the inability to respond to requests from practice indicates the need for methodological assistance), and finally by the contribution that science itself makes to general scientific or philosophical methodology. Thus, the task arises to indicate some specific features of the "relationship" between psychology and methodology in the broad sense of the word.

The main thing is that psychology is one of the sciences about man, therefore, the initial principles of psychological research and its results cannot but have a pronounced ideological coloring, they are often directly related to the idea of the essence of man and his relationship to the world.

Another important feature of psychological knowledge, which determines its methodological significance, was noted by Aristotle in the first lines of his treatise on the soul. “Recognizing knowledge as a beautiful and worthy deed, but placing one knowledge above the other either by the degree of perfection, or because it is knowledge of something more sublime and convincing, it would be correct for one or the other reason to give the study of the soul one of the first places. that the knowledge of the soul contributes a lot to the knowledge of all truth, especially the knowledge of nature. development.

When considering the importance of psychology for methodology, it is legitimate to pose another question that has hardly been discussed in the literature. The point is that psychology has obtained data that make it possible to substantiate the need for methodological knowledge as some kind of prediction, without which the cognitive activity of a collective or individual subject is generally impossible. The need for prior knowledge in one form or another is clearly fixed already at the level of sensory cognition and is clearly manifested in the case of rational, and even more so, scientific cognition proper. Recognition of the most important role of such foreknowledge automatically leads to the requirement for the most deep reflection of it, which is the subject of methodology.

In making a contribution to methodological knowledge in general, psychology should all the more highly value the significance of methodology for itself. Moreover, psychologists have long emphasized her special need for help from methodology and the impossibility of developing guidelines for the construction and development of psychological science based on psychological knowledge itself. The very "possibility of psychology as a science is a methodological problem first of all" - noted in the work "The Historical Meaning of the Psychological Crisis", specially devoted to the discussion of the methodological problems of constructing scientific psychology. "Not a single science has so many difficulties, insoluble controversies, the combination of different in one thing, as in psychology. The subject of psychology is the most difficult of everything in the world, the least amenable to study; what is expected of him. " And further: "No other science represents such a variety and completeness of methodological problems, such tight knots, insoluble contradictions, as ours. Therefore, one cannot take a single step here without taking a thousand preliminary calculations and warnings."

For more than half a century that have passed since the writing of this work (published in 1982), the severity of the problems he formulated has not diminished

So, the first reason for the special interest of psychology in methodological developments lies in the complexity and versatility of the subject of research itself, its qualitative originality.

The second reason is that psychology has accumulated a huge amount of empirical material that simply cannot be covered without new methodological approaches. Both of these reasons are closely related to each other, as well as with a dozen others, which could be listed, justifying the special need of psychology for methodological guidelines. But we would like to draw your attention to one more and, perhaps, the most important reason for extremely high requirements for the methodological literacy of any psychological research, especially since this requirement is rarely discussed in the pages of psychological literature. We are talking about the special responsibility of the psychologist for the results and conclusions published by him about the essence of the mental and the determinants of its development.

Conclusions based on the unlawful generalization of the results of private studies, the transfer of data obtained from the study of animals to humans, and from the study of patients - to healthy people, etc. lead to the circulation in the public consciousness of ideas that distortedly reflect the nature of man and lead to negative social -political consequences.

A great responsibility lies with psychologists who work with people and participate in the diagnosis and forecasting of professional suitability, level of development, in the formulation of a clinical diagnosis, in the conduct of a forensic psychological examination. Working in these areas requires good methodological and methodological training.

Attention should be paid to the widespread and typical for psychology methodological error, which consists in the uncritical borrowing and use of approaches and procedures (primarily tests) developed for people of a completely different culture, a different socio-economic community.

In this chapter, we have tried to summarize the existing ideas about the methodology, its objectives, levels and functions. In conclusion, it is necessary to warn against the prescription understanding of its functions. Both scientific and methodological work require creativity. Methodologically correct work requires creativity even more. Attempts by psychologists to apply new conceptual schemes developed in the modern methodology of science run up against two kinds of difficulties. The first difficulty is associated with the presence of a certain number of "degrees of freedom" in any such conceptual scheme. So, for example, among specialists in the field of the systems approach (or systems methodology), there are discussions about its essence, the limits of applicability, attitude to theory, empiricism and practice.

Discussions also concern the problems of classification of systems, their structure and functions. The systems are static and dynamic, rigid and flexible, self-adjusting and self-organizing, hierarchical and heterarchical, homogeneous and heterogeneous, correlative and combinative, permanent and temporary. There are difficulties both in the classification of components, which can be substantial and functional, and in determining the types of relationships between them. Links can be direct and reverse. Both are useful for characterizing the processes of functioning and development. Consequently, within the framework of systemic studies, there is a wide space of conceptual schemes, each of which was designed to describe real objects. There are also abstract constructions that have not yet found a real analogue. The task of using this richest apparatus for describing various types of reality cannot be solved by an arbitrary choice. It is with this that the second difficulty is connected, which already relates to psychology. It is due to the non-uniqueness of interpretations of the mental, as well as the variety of tasks that are posed when studying such a complex object as it is. The systems approach is hardly advisable to apply in any psychological research. There is a considerable number of studies included in the golden fund of psychological science, which were carried out without the influence of systemic ideas and in which they are difficult to subtract or even "read". At the same time, there are entire trends in psychological science in which the systems approach, or at least systemic ideas, originated before the works of Ludwig von Bertalanffy and before the emergence of the "systemic movement" in the methodology of science. Systemic gestalpsychology, systemic genetic epistemology of J. Piaget, as well as the molar approach in Hull's psychology. By the way, Bertalanffy also referred to these directions, but this did not save them from the subsequent and, as is well known, harsh criticism that continues in the world of psychological science to this day. We are talking about this in order to emphasize that by itself this or that methodological conceptual scheme, no matter what merits it possesses, does not exempt one from serious theoretical work in psychology as such. Now there is no need to prove that the systems approach is not suitable for organizing the data obtained (and received) in traditional functional psychology, or for psychology that considers the brain the subject of its research (although, of course, there is no reason to doubt the applicability of the systems approach to brain physiology) ...

We do not doubt the fruitfulness of the application of the systems approach in psychology. But the difficulties indicated above cannot be overcome mechanically, that is, by an arbitrary preference for a certain conceptual scheme and a certain idea of the subject of psychology. Here it is necessary to conduct a kind of experimental-methodological research, the results of which would help to clarify and substantiate both the methodological scheme itself and the idea of the subject of psychology. Such research is not only a matter of the future. It is already under way both in general psychology and in its applied fields. Moreover, there are interesting results obtained on the basis of convergence and even interpenetration, for example, functional-structural schemes developed within the framework of the systems approach and conceptual schemes developed within the framework of the activity approach in psychology. The naturalness for psychology of combining and interpenetrating systemic and active concepts and approaches is due to the fact that they originated in Marxist philosophy. The activity approach in psychology also influences the development of general systemic problems, leads to the enrichment of the methods of logical means of the systemic approach. The converse is also true. True, it is too early to overestimate the available results and underestimate the existing difficulties in the interpenetration of both approaches.

Introduction

"An experiment cannot confirm a theory, it can only refute it." A. Einstein

Methodological issues are traditionally relevant in the modern scientific world. The methodology is a theoretical substantiation of the optimal algorithm of activity, both cognitive and practical, and therefore is significant and discussed outside the time frame.

Science itself is called upon to ensure the optimality of any activity, to enable the subject to achieve the set goal, following a theoretically based algorithm. And for this, science needs its own methodology that optimizes research activities.

The question of the methodology of science began to be widely discussed in the literature, including in connection with the idea that arose at the beginning of the 20th century that the sciences of man, culture, society have their own problems and their own methods of research. And today, the debate about the demarcation of the methodology of natural and social sciences and humanities does not stop. The question is raised about the possibility of using natural scientific methods in social and humanitarian research, i.e. the question of the continuity of methods. At the same time, if we analyze the results of the development of the sciences about man and society over the past 30 years, then there is reason to believe that their development is moving along the path of rapprochement with the natural sciences.

The existing levels of scientific knowledge (empirical and theoretical) also highlight certain controversial issues. Until the middle of the twentieth century, the so-called "standard approach" prevailed in methodological research, according to which theory and its relationship with experience were chosen as the initial unit of methodological analysis. But then it turned out that the processes of functioning, development and transformation of theories cannot be adequately described, if we abstract from their interaction. It also turned out that empirical research is intricately intertwined with the development of theories and it is impossible to imagine testing the theory by facts without taking into account the previous influence of theoretical knowledge on the formation of experimental facts of science. But then the problem of the interaction of theory with experience appears as a problem of the relationship with the empirical system of theories that form a scientific discipline. In this regard, a separate theory and its empirical basis can no longer be taken as a unit of methodological analysis. Such a unit is a scientific discipline as a complex interaction of knowledge of the empirical and theoretical levels, associated in its development with other scientific disciplines.

History of methodology

The history of methodology goes back to the Ancient World. Socrates, who lived in the 5th century. BC Chr. understood the importance of methodology in knowledge and developed his own method of questions and answers - the method of Socrates (it is not for nothing that Socrates is considered a great teacher, and Plato grew up among his students). Socrates believed in a single Divine Spirit, immortality of the soul, judgment and retribution in the afterlife. His faith contradicted the state, and the authorities, accusing him of corrupting young people with their ideas, sentenced him to hemlock poisoning.

Plato also believed in the immortality of the soul and recognized the possibility of knowledge through revelation.

The history of any branch of science is not complete without Aristotle. Methodology is no exception, the contribution of Aristotle to which consists primarily in the development of logic. Al-Farabi (an Arab philosopher of the 10th century, commentator of Aristotle) interpreted the task of this science as an "art" that leads the mind to correct thinking, whenever there is a possibility of error, and which indicates all precautions against error whenever any or a conclusion with the help of reason.

To create a solid foundation for practical thinking, Aristotle attempted to analyze linguistic forms and explore the formal structure of the process of inference and conclusions, regardless of their content. Aristotle's research boiled down to finding such forms of reasoning that, if used correctly, would not violate the truth of the starting points. Truth was not understood as some kind of absolute. The idea was different. How to build reasoning so that they only support the initial position (it was necessary to convince opponents of its truth), and not refute it.

Aristotle's logic was based on the following provisions:

1. The premises of the reasoning are true. At the same time, we emphasize once again: the truth was set by the prover, that is, it was about the fact that the premises are true for him, in his opinion, and not absolute.

2. Correctly applied principles from premises to statements must preserve the truth of the statements obtained, i.e. true premises give rise to true consequences.

The basic principles expressing the general requirements that reasoning and logical operations with thoughts must satisfy in order to achieve truth by rational methods were:

1. The principle of identity - in the process of reasoning, using a certain term, we must use it in the same sense, understand by it something definite. Although objects that exist in reality are constantly changing, something unchanging stands out in the concepts of these objects. In the process of reasoning, you cannot change concepts without a special reservation. In other words, if you change the meaning of a term, then stipulate it, otherwise you will be misunderstood (for example, the term mass means different things in physics, chemistry, technology, everyday life, etc.), so you need to know exactly which concept is expressed by this or that word or combination.

2. The principle of consistency requires that thinking be consistent; so that, while asserting something about something, we do not deny the same about the same in the same sense, that is, it forbids simultaneously accepting some assertion and its denial. Contradictions in linguistic contexts are sometimes implicit. So, the famous dictum of Socrates "I know that I know nothing" hides a contradiction.

3. The principle of the excluded middle requires not to reject the statement and its denial. The statement "A" and the negation of "A" cannot be rejected at the same time, since one of them is necessarily true, since an arbitrary situation either has or does not take place in reality. According to this principle, it is necessary to clarify our concepts so that it is possible to give answers to alternative questions. "Has the sun risen or not?" It is necessary to agree to consider, for example, that the Sun has risen, if it all rose above the horizon (or just a little seemed from beyond the horizon), but one thing! Having clarified the concepts, we can say about two judgments, one of which is the negation of the other, that one of them is necessarily true.

4. The principle of sufficient reason requires that any statement be substantiated to some extent, that is, the truth of statements cannot be taken on faith. The judgments from which the statement is derived when justifying it (if we consider the rules of logic as data) are called grounds, therefore the principle in question is called the principle of sufficient reason, which means: there must be enough grounds to deduce the statement from the initial premises.

This so-called formal logic has existed in an almost unchanged form from the time of Aristotle to our time. At the beginning of the twentieth century, a symbolic, or mathematical logic about utility was developed, to which Leibniz said: "The only way to improve our conclusions is to make them, like those of mathematicians, visual, so that we can find errors with our eyes, and if a dispute arises among people, it is necessary to say "Let's count!" And then without any special formalities it will be possible to see who is right. " His idea was realized at the beginning of the twentieth century.

So, the truth of the conclusions was determined by the correspondence of the conclusion to certain rules and the truth of the initial premises. And the truth of the initial premises was determined by the opinion of the author of the reasoning. They did not focus on this, and gradually reason and logical thinking began to be considered a generator of truths.

The idea that human thinking is rational, that all human reasoning has verbal premises is wrong. The rational component in thinking occupies a limited place, and the verbal component - only the part allotted to it. There is emotional reasoning that is generated on the basis of hidden analogies and associations, and is not described by rational logical schemes.

On the other hand, science must be based on language as the only means of conveying messages, so where the problem of unambiguity is of primary importance, logical schemes are needed.

As W. Heisenberg wrote: “In natural science we are trying to deduce the singular from the general: a single phenomenon must be understood as a consequence of simple general laws. These general laws, when formulated in language, can contain only a few few concepts, because, otherwise, laws would not be simple and not universal.From these concepts an infinite variety of possible phenomena must be deduced, and at the same time not only qualitatively and approximately, but also with great accuracy in relation to every detail. inaccurate, would never allow such a conclusion to be drawn.If a chain of conclusions follows from the given premises, then the total number of possible members in the chain depends on the accuracy of the premises.Therefore, in natural science, the basic concepts of general laws must be determined with extreme accuracy, and this is possible only with the help mathematical abstraction ".

Aristotle's rationalism led him to reject the Platonic concept of the possibility of knowledge through revelation. In this he shared the views of Empedocles on knowledge through the five senses - sight, hearing, smell, touch and taste. This position limited the framework of cognition by objects of the physical world. Aristotle accumulated and ordered vast knowledge in various sciences at that time, his explanations are very logical and rationalistic.

Aristotle's scientific method included logical constructions and appeal to authorities (for example, the planets are in a perfect supra-moon region and therefore must move along perfect trajectories - circles). On the basis of this method, in his works "On the Soul", "Physics", "Metaphysics" Aristotle gave a complete explanation of reality without a single mention of God.

However, it was the dominance of the rationalistic method of Aristotle in the system of cognition that delayed the development of scientific thinking for a huge period of time, almost 2000 years in length. The teachings of the Peripatetics, built on the ideas of Aristotle, were even recognized as the official doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church. The approval of new methods of natural science knowledge is associated with the names of F. Bacon, R. Descartes, G. Galileo, I. Newton.

Galileo, abandoned a purely rationalistic study of nature and began to make maximum use of observation and experiment, which was facilitated by his invention of a telescope, and then a clock. Together with the English thinker Francis Bacon, Galileo is considered the founder of the inductive method - the main method of scientific research. The scientific method of induction includes:

1. Collection and accumulation of empirical data.

2. Inductive generalization of accumulated data with the formulation of hypotheses and models.

3. Testing hypotheses by experiment based on the deductive method - a logically correct conclusion from an axiomatic assumption, the correctness of which is unprovable within the framework of the hypothetical-deductive method.

4. Rejection of inappropriate models and hypotheses and the design of suitable ones in theory.

Thus, the construction of a scientific theory assumes that a hypothesis is put forward on the basis of initial observations, then the first experiment is set up to test this hypothesis (which can be corrected in the course of experiments), then the experiments are set up one after another until all of them are satisfactorily explained within the framework of a single theory.

This method is so clear that the thought arises that scientists always follow it. However, this is not so - in many cases, when it is difficult or even fundamentally impossible to conduct experiments, dubious hypotheses are elevated to the rank of theory. An example of this are such fundamentally unverifiable and unobservable "theories" as Darwinism, the "theory" of the big bang, "theories" of the evolution of the Earth and the origin of the solar system.