Musical culture of romanticism: aesthetics, themes, genres and musical language. Analysis of the category of tragic in German romanticism Approximate word search

Ideological and artistic movement in European and American culture at the end of the 18th - 1st half of the 19th centuries. Born as a reaction to the rationalism and mechanism of the aesthetics of classicism and the philosophy of the Enlightenment, which was established in the era of the revolutionary breakdown of feudal society, the former, seemingly unshakable world order, romanticism (both as a special kind of worldview and as an artistic direction) has become one of the most complex and internally contradictory phenomena in the history of culture.

Disappointment in the ideals of the Enlightenment, in the results of the Great French Revolution, the denial of the utilitarianism of modern reality, the principles of bourgeois practicalism, the victim of which was human individuality, a pessimistic view of the prospects for social development, the mentality of "world sorrow" was combined in romanticism with the desire for harmony of the world order, spiritual integrity of the individual , with a gravitation towards the "infinite", with the search for new, absolute and unconditional ideals. A sharp discord between ideals and oppressive reality evoked in the minds of many romantics a painfully fatalistic or indignant feeling of double world, a bitter mockery of the discrepancy between dreams and reality, elevated in literature and art to the principle of "romantic irony".

The deepest interest in the human personality inherent in romanticism, understood by romantics as a unity of individual external characteristic and unique internal content, became a kind of self-defense against the increasing leveling of personality. Penetrating into the depths of a person's spiritual life, literature and the art of romanticism simultaneously transferred this acute sensation of the characteristic, original, unique to the fate of nations and peoples, to historical reality itself. The tremendous social shifts that took place before the eyes of the romantics made the progressive course of history clearly visible. In his best works, romanticism rises to the creation of symbolic and at the same time vital images associated with modern history. But images of the past, drawn from mythology, ancient and medieval history, were embodied by many romantics as a reflection of real conflicts.

Romanticism became the first artistic direction in which the awareness of the creative personality as a subject of artistic activity was clearly manifested. Romantics openly proclaimed the triumph of individual taste, complete freedom of creativity. Attaching decisive importance to the creative act itself, destroying the obstacles that held back the artist's freedom, they boldly equated the high and the low, the tragic and the comical, the ordinary and the unusual.

Romanticism captured all spheres of spiritual culture: literature, music, theater, philosophy, aesthetics, philology and other humanities, plastic arts. But at the same time, he was no longer the universal style that was classicism. Unlike the latter, romanticism had almost no state forms of its expression (therefore, it did not significantly affect architecture, influencing mainly garden and park architecture, architecture of small forms and the direction of the so-called pseudo-Gothic). Being not so much a style as a social artistic movement, romanticism paved the way for the further development of art in the 19th century, which took place not in the form of comprehensive styles, but in the form of separate trends and trends. Also, for the first time in romanticism, the language of artistic forms was not completely rethought: to a certain extent, the stylistic foundations of classicism were preserved, significantly modified and rethought in certain countries (for example, in France). At the same time, within the framework of a single style direction, the individual style of the artist received great freedom of development.

Romanticism has never been a clearly defined program or style; this is a wide range of ideological and aesthetic tendencies, in which the historical situation, country, interests of the artist created certain accents.

Musical romanticism, which significantly manifested itself in the 20s. XIX century, was a historically new phenomenon, but revealed connections with the classics. Music took possession of new means that made it possible to express both the strength and the subtlety of a person's emotional life, lyricism. These aspirations made many musicians in common in the second half of the 18th century. literary movement "Storms and Onslaught".

Musical romanticism has historically been prepared by the literary romanticism that preceded it. In Germany - among the "Jena" and "Heidelberg" romantics, in England - among the poets of the "lake" school. Further, musical romanticism was significantly influenced by such writers as Heine, Byron, Lamartine, Hugo, Mickiewicz.

The most important spheres of creativity of musical romanticism include:

1. Lyrics - is of paramount importance. In the hierarchy of the arts, music was given the most honorable place, since feeling reigns in music and therefore the creativity of the romantic artist finds its highest goal in it. Consequently, music is the lyrics, it allows a person to merge with the "soul of the world", music is the antipode of prosaic reality, it is the voice of the heart.

2. fantasy - acts as freedom of imagination, free play of thought and feeling, freedom of knowledge, striving into the world of the strange, wonderful, unknown.

3. folk and national-original - the desire to recreate in the surrounding reality authenticity, primacy, integrity; interest in history, folklore, the cult of nature (primordiality). Nature is a refuge from the troubles of civilization; it consoles a restless person. Characterized by a large contribution to the collection of folklore, as well as a common striving for the correct transmission of the folk-national artistic style ("local color") - this is a common feature of the musical romanticism of different countries and schools.

4. characteristic - strange, eccentric, caricature. To designate it is to break through the leveling gray veil of ordinary perception and touch the colorful, seething life.

Romanticism sees in all types of art a single meaning and goal - merging with the mysterious essence of life, the idea of the synthesis of arts acquires a new meaning.

“The aesthetics of one art is the aesthetics of another,” said R. Schumann. The combination of different materials increases the impressive power of the artistic whole. In a deep and organic fusion with painting, poetry and theater, new opportunities have opened up for art. In the field of instrumental music, the principle of programming has acquired great importance, i.e. inclusion of literary and other associations in the composer's intention and the process of music perception.

Romanticism is especially widely represented in the music of Germany and Austria (F. Schubert, E.T.A. Hoffmann, K.M. Weber, L. Spor), then - the Leipzig School (F. Mendelssohn-Bartholdi and R. Schumann). In the second half of the XIX century. - R. Wagner, I. Brahms, A. Bruckner, H. Wolf. In France - G. Berlioz; in Italy - G. Rossini, G. Verdi. F. Chopin, F. List, J. Meyerbeer, N. Paganini are of common European importance.

The role of miniatures and large one-part forms; new interpretation of cycles. Enrichment of expressive means in the field of melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, instrumentation; renewal and development of classical patterns of form, development of new compositional principles.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, late romanticism reveals the hypertrophy of the subjective principle. Romantic tendencies also manifested themselves in the work of 20th century composers. (D. Shostakovich, S. Prokofiev, P. Hindemith, B. Britten, B. Bartok and others).

For all the differences from realism in aesthetics and method, romanticism has deep inner connections with it. They are united by a sharply critical position in relation to epigone classicism, the desire to free themselves from the fetters of classicist canons, to break out into the open space of life's truth, to reflect the wealth and diversity of reality. It is no coincidence that Stendhal, in his treatise "Racine and Shakespeare" (1824), which puts forward new principles of realistic aesthetics, appears under the banner of romanticism, seeing in it the art of modernity. The same can be said about such an important, programmatic document of romanticism as Hugo's Preface to the drama Cromwell (1827), which openly voiced a revolutionary call to break the rules pre-established by classicism, outdated art norms and ask advice only from life itself.

Around the problem of romanticism there have been and continue to be a great controversy. This controversy is due to the complexity and contradictions of the very phenomenon of romanticism. There were many delusions in solving the problem, which resulted in underestimating the achievement of romanticism. The very application of the concept of romanticism to music was sometimes questioned, while it was in music that he gave the most significant and enduring artistic values.

In the 19th century, romanticism was associated with the flourishing of the musical culture of Austria, Germany, Italy, France, the development of national schools in Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and later in other countries - Norway, Finland, Spain. The greatest musicians of the century - Schubert, Weber, Schumann, Rossini and Verdi, Berlioz, Chopin, Liszt, Wagner and Brahms, right up to Bruckner and Mahler (in the West) - either belonged to the romantic movement or were associated with them. Romanticism and its traditions played a big role in the development of Russian music, in their own way manifested in the work of the composers of “a mighty handful of both Tchaikovsky, and, further, Glazunov, Taneyev, Rachmaninov, Scriabin.

Soviet scientists have revised much in their views on romanticism, especially in the works of the last decade. A tendentious, vulgar-sociological approach to romanticism as a product of feudal reaction, an art that leads away from reality into the world of the artist's arbitrary fantasy, that is, anti-realist in its essence, is becoming obsolete. The opposite point of view, which places the criteria for the value of romanticism entirely in dependence on the presence in it of elements of another, realistic method, did not justify itself either. Meanwhile, a truthful reflection of the essential aspects of reality is inherent in romanticism itself in its most significant, progressive manifestations. Objections are also raised by the unconditional opposition of romanticism to classicism (after all, many advanced artistic principles of classicism had a significant impact on romanticism), and the exclusive emphasis on the pessimistic features of the romantic worldview, the idea of "world sorrow", its passivity, reflection, subjectivist limitation. This angle of view influenced the general concept of romanticism in the musicological works of the 1930s – 1940s, expressed, in particular, in article II. Sollertinsky "Romanticism, its general and musical aesthetics". Along with the work of V. Asmus "The Musical Aesthetics of Philosophical Romanticism" 4, this article is one of the first significant generalizing works on romanticism in Soviet musicology, although the time has made significant amendments to some of its main provisions.

At present, the assessment of romanticism has become more differentiated, its various tendencies are considered in accordance with historical periods of development, national schools, arts and major artistic personalities. The main thing is that romanticism is evaluated in the struggle of opposite tendencies within itself. Particular attention is paid to the progressive aspects of romanticism as the art of a subtle culture of feeling, psychological truth, emotional wealth, art that reveals the beauty of the human heart and spirit. It was in this area that romanticism created immortal works and became our ally in the struggle against the anti-humanism of modern bourgeois avant-gardeism.

In the interpretation of the concept of "romanticism" it is necessary to distinguish two main, interconnected categories - artistic direction and method.

As an artistic trend, romanticism emerged at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries and developed in the first half of the 19th century, during a period of acute social conflicts associated with the establishment of the bourgeois system in Western Europe after the French bourgeois revolution of 1789-1794.

Romanticism went through three stages of development - early, mature and late. At the same time, there are significant temporary differences in the development of romanticism in different Western European countries and in different types of art.

The earliest literary schools of romanticism emerged in England (lake school) and Germany (Viennese school) at the very end of the 18th century. In painting, romanticism originated in Germany (F.O. Runge, KD Friedrich), although its true homeland is France: it was here that the general battle of classicist painting was fought by the heralds of romanticism Kernko and Delacroix. In music, romanticism received its earliest expression in Germany and Austria (Hoffmann, Weber, Schubert). Its beginning dates back to the second decade of the 19th century.

If the romantic trend in literature and painting basically completes its development by the middle of the 19th century, then the life of musical romanticism in the same countries (Germany, France, Austria) is much longer. In the 30s, he entered only the period of his maturity, and after the revolution of 1848-1849, his last stage began, lasting approximately until the 80s and 90s (late Liszt, Wagner, Brahms; the work of Bruckner, early Mahler). In some national schools, for example, in Norway, Finland, the 90s are the culmination of the development of romanticism (Grieg, Sibelius).

Each of these stages has its own significant differences. Particularly significant shifts took place in late romanticism — in its most complex and contradictory period, marked at the same time by new achievements and the emergence of crisis moments.

The most important socio-historical prerequisite for the emergence of the romantic trend was the dissatisfaction of various strata of society with the results of the French revolution of 1789-1794, that bourgeois reality, which, according to F. Engels, turned out to be "a caricature of the brilliant promises of the enlighteners." Speaking about the ideological atmosphere in Europe during the emergence of romanticism, Marx in his famous letter to Engels (dated March 25, 1868) notes: “The first reaction to the French Revolution and the Enlightenment associated with it, naturally, was to see everything in the medieval, romantic light, and even people like Grimm are not exempt from it. " In the quoted passage, Marx speaks of the first reaction to the French Revolution and the Enlightenment, which corresponds to the initial stage in the development of romanticism, when reactionary elements were strong in it (the second reaction, as is known, was linked by Marx with the direction of bourgeois socialism). They were most actively expressed in the idealistic premises of philosophical and literary romanticism in Germany (for example, among the representatives of the Viennese school - Schelling, Novalis, Schleiermacher, Wackenroder, the Schlegel brothers) with its cult of the Middle Ages, Christianity. The idealization of medieval feudal relations is inherent in literary romanticism in other countries (lake school in England. Chateaubriand, de Maistre in France). However, it would be wrong to extend the cited statement of Marx to all trends of romanticism (for example, to revolutionary romanticism). Generated by enormous social upheavals, romanticism was not, and indeed could not be, a unified trend. It developed in the struggle of opposite tendencies - progressive and reactionary.

L. Feuchtwanger recreated a vivid picture of the era, its spiritual contradictions in the novel "Goya or the Hard Path of Knowledge":

“Humanity is tired of the passionate efforts to create a new order in the shortest possible time. At the cost of the greatest exertion, the peoples tried to subordinate social life to the dictates of reason. Now the nerves were gone, from the blinding bright light of reason people ran back into the twilight of feelings. All over the world, old reactionary ideas were being spoken again. From the cold of thought, everyone strove for the warmth of faith, piety, sensitivity. Romantics dreamed of the revival of the Middle Ages, poets cursed a clear sunny day, admired the magical light of the moon. " Such is the spiritual atmosphere in which the reactionary current within romanticism was ripening, the atmosphere that gave rise to such typical works as the novel by Chateaubrnack "Rene" or the novel by Novalis "Heinrich von Ofterdingen". However, “new ideas, clear and precise, already dominated the minds,” continues Feuchtwanger, “and it was impossible to root them out. Privileges, hitherto unshakable, were shaken, absolutism, the divine origin of power, class and caste differences, the preferential rights of the church and the nobility - everything was questioned. "

A. M. Gorky correctly emphasizes the fact that romanticism is a product of a transitional era, he characterizes it as “a complex and always more or less vague reflection of all shades, feelings and moods that embrace society in transitional epochs, but its main note is the expectation of something. something new, anxiety before the new, a hasty, nervous desire to learn this new. "

Romanticism is often defined as a rebellion against the bourgeois enslavement of the human person / it is rightly associated with the idealization of extra-capitalist forms of life. It is from here that the progressive and reactionary utopias of romanticism are born. A keen sense of the negative sides and contradictions of the emerging bourgeois society, the protest against the transformation of people into "mercenaries of industry" 3 was the strong point of romanticism.! "Awareness of the contradictions of capitalism puts them (romantics. - N. N.) above the blind optimists who deny these contradictions," wrote V. I. Lenin.

The different attitude to the ongoing social processes, to the struggle between the new and the old, gave rise to deeply fundamental differences in the very essence of the romantic ideal, in the ideological orientation of artists of different romantic trends. Literary criticism distinguishes between progressive and revolutionary currents in romanticism, on the one hand, and reactionary and conservative currents, on the other. Emphasizing the opposition of these two trends in romanticism, Gorky calls them “active; and "passive". The first of them "seeks to strengthen the will of man to live, to arouse in him a rebellion against reality, against any oppression of it." The second, on the contrary, "tries or to reconcile a person with reality, embellishing it, or to distract from reality." After all, the dissatisfaction of the romantics with reality was twofold. "Disorder, discord, discord," wrote Pisarev on this matter. Lenin to the address of economic romanticism: ". The plans of" romanticism are portrayed as very easily realizable precisely because of the ignorance of real interests, which is the essence of romanticism. "

Differentiating the positions of economic romanticism, criticizing Sismondi's projects, V. I. Lenin spoke positively about such progressive representatives of utopian socialism as Owen, Fourier, Thompson: machine industry. They looked in the same direction as the actual development; they really were ahead of this development ”3. This statement can also be attributed to the progressive, primarily revolutionary, romantics in art, among whom the figures of Byron, Shelley, Hugo, Manzoni stood out in the literature of the first half of the 19th century.

Of course, living creative practice is more complex and richer than a scheme of two currents. Each trend had its own dialectic of contradictions. In music, this differentiation is especially difficult and hardly applicable.

The heterogeneity of romanticism was sharply revealed in its attitude to the Enlightenment. Romanticism's reaction to enlightenment was by no means direct and one-sidedly negative. The attitude towards the ideas of the French Revolution and the Enlightenment was a knot in the collision of various directions of romanticism. This was clearly expressed, for example, in the opposite of the positions of the English romantics. While the poets of the lake school (Coleridge, Wordsworth and others) rejected the philosophy of the Enlightenment and the traditions of classicism associated with it, the revolutionary romantics Shelley and Byron defended the idea of the French Revolution of 1789-1794, and in their work they followed the traditions of heroic citizenship, typical for revolutionary classicism.

In Germany, the most important link between enlightenment classicism and romanticism was the Sturm und Drang movement, which prepared the aesthetics and images of German literary (partly musical - early Schubert) romanticism. Educational ideas are heard in a number of journalistic, philosophical and artistic works of German romantics. So, "Hymn to Humanity" Fr. Hölderlin, an admirer of Schiller, was a poetic transposition of Rousseau's ideas. The ideas of the French Revolution are defended by Fr. Schlegel, the Jena romantics appreciated Goethe. In the philosophy and aesthetics of Schelling, the then generally recognized head of the Romantic school, there are connections with Kant and Fichte.

In the work of the Austrian playwright, contemporary of Beethoven and Schubert - Grillparzer - romantic and classicist elements (an appeal to antiquity) are closely intertwined. At the same time Novalis, called by Goethe "the emperor of romanticism", writes treatises and novels sharply hostile to the educational ideology ("Christianity or Europe", "Heinrich von Ofterdingen").

In musical romanticism, especially in Austrian and German, continuity from classical art is clearly visible. It is known how significant the connections of the early romantics - Schubert, Hoffmann, Weber - with the Viennese classical school (especially with Mozart and Beethoven) are. They are not lost, but in some way and strengthened in the future (Schumann, Mendelssohn), up to its later stage (Wagner, Brahms, Bruckner).

At the same time, progressive romantics opposed academism, expressed an acute dissatisfaction with the dogmatic provisions of classicist aesthetics, criticized the schematism and one-sidedness of the rationalist method. The most acute opposition to the French classicism of the 17th century was marked by the development of French art in the first third of the 19th century (although here romanticism and classicism interbred, for example, in the work of Berlioz). The polemical works of Hugo and Stendhal, the statements of Georges Sand, Delacroix are permeated with hot criticism of the classicism aesthetics of both the 17th and 18th centuries. Among writers, it is directed against the rational-conventional principles of classicist drama (in particular, against the unity of time, place and action), the immutable distinction between genres and aesthetic categories (for example, the sublime and the ordinary), the limitation of the spheres of reality that can be reflected by art. In their striving to show all the contradictory versatility of life, to link together its most diverse aspects, romantics turn to Shakespeare as an aesthetic ideal.

The dispute with the aesthetics of classicism, going in different directions and with varying degrees of acuteness, also characterizes the literary movement in other countries (in England, Germany, Poland, Italy and very brightly in Russia).

One of the most important stimuli for the development of progressive romanticism was the national liberation movement, awakened by the French Revolution, on the one hand, and the Napoleonic wars, on the other. It gave rise to such valuable aspirations of romanticism, such as interest in national history, the heroism of popular movements, in the national element and folk art. All this inspired the struggle for a national opera in Germany (Weber), determined the revolutionary-patriotic orientation of romanticism in Italy, Poland, and Hungary.

The romantic movement that swept the countries of Western Europe, the development of national romantic schools in the first half of the 19th century gave an unprecedented impetus to the collection, study and artistic development of folklore - literary and musical. German romantic writers, continuing the traditions of Herder and the Sturmers, collected and published monuments of folk art - songs, ballads, fairy tales. It is difficult to overestimate the significance of the collection The Wonderful Horn of the Boy, compiled by L. I. Arnim and K. Brentano, for the further development of German poetry and music. In music, this influence goes through the entire 19th century, right up to Mahler's song cycles and symphonies. The brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, collectors of folk tales, did a lot to study Germanic mythology and medieval literature, laying the foundation for scientific Germanic studies.

In the field of the development of Scottish folklore, the merits of V. Scott are great, the Polish - A. Mitskevich and Y. Slovatsky. In musical folklore, which was at the cradle of its development at the beginning of the 19th century, the names of composers G.I. Fogler (teacher of K.M. Weber) in Germany, O. Kolberg in Poland, A. Horvat in Hungary, etc.

It is known what a fertile soil folk music was for such brightly national composers as Weber, Schubert, Chopin, Schumann, Liszt, Brahms. The appeal to this "inexhaustible treasury of melodies" (Schumann), deep comprehension of the spirit of folk music, genre and intonation foundations determined the power of artistic generalization, democracy, the enormous universal human impact of the art of these romantic musicians.

Like any artistic direction, romanticism is based on a certain creative method peculiar to it, the principles of artistic reflection of reality, an approach to it, and understanding it, typical for this direction. These principles are determined by the artist's worldview, his position in relation to contemporary social processes (although, of course, the connection between the artist's worldview and creativity is by no means direct).

Without touching on the essence of the romantic method, we note that some aspects of it find expression in later (in relation to the direction) historical periods. However, going beyond the specific historical direction, it would be more accurate to speak of romantic traditions, continuity, influences or romance as an expression of a certain elevated emotional tone associated with the thirst for beauty, with the desire to "live a life tenfold."

Thus, for example, at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the revolutionary romanticism of early Gorky flared up in Russian literature; the romance of dreams, of poetic fantasy determines the originality of A. Green's work, finds its expression in the early Paustovsky. In Russian music of the beginning of the 20th century, the works of Scriabin and early Myaskovsky are marked by the features of romanticism, which at this stage merges with symbolism. In this regard, it is worth recalling Blok, who believed that symbolism "is associated with romanticism deeper than all other currents."

In Western European music, the line of development of romanticism in the 19th century was continuous until such late manifestations as Bruckner's last symphonies, Mahler's early works (late 80s-90s), some symphonic poems by R. Strauss (Death and Enlightenment , 1889; "Thus Spoke Zarathustra", 1896) and others.

In the characterization of the artistic method of romanticism, many factors usually appear, but they cannot give an exhaustive definition. There are disputes about whether it is possible at all to give a generalizing definition of the method of romanticism, because, indeed, it is necessary to take into account not only the opposite trends in romanticism, but also the specifics of the type of art, time, national school, creative individuality.

And yet, I think, it is possible to generalize the most essential features of the romantic method B in general, otherwise it would not be possible to speak of it as a method in general1. In this case, it is very important to take into account the complex of defining features, since, taken separately, they can be present in another creative method.

Belinsky has a generalizing definition of the two essential aspects of the romantic method. "In its closest and most essential meaning, romanticism is nothing but the inner world of a person's soul, the innermost life of his heart," writes Belinsky, noting the subjective-lyrical nature of romanticism, its psychological orientation. Developing this definition, the critic clarifies: "His sphere, as we said, is the entire inner soulful life of a person, that mysterious soil of the soul and heart, from which all vague aspirations for the best and the sublime rise, trying to find satisfaction in the ideals created by fantasy." This is one of the main features of romanticism.

Another fundamental feature of it is defined by Belinsky as "a deep inner discord with reality." II although Belinsky gave a sharply critical connotation to the last definition (the desire of romantics to go "past life"), he puts the right emphasis on the conflicting perception of the world by romantics, the principle of opposing the desired and the actual, caused by the conditions of the social life of the top era.

Similar provisions were encountered earlier in Hegel: “The world of the soul triumphs over the victory over the external world. and as a result of this, the sensory phenomenon is devalued. " Hegel notes the gap between striving and action, the “longing of the soul for the ideal” instead of action and implementation4.

It is interesting that A. V. Schlegel came to a similar description of romanticism, but from different positions. Comparing ancient and modern art, he defined Greek poetry as the poetry of joy and possession, capable of concretely expressing the ideal, and romantic as the poetry of melancholy and longing, incapable of embodying the ideal in its striving for the infinite5. Hence, the difference in the character of the hero follows: the ancient ideal of man is inner harmony, the romantic hero is an inner split.

So, the striving for the ideal and the gap between dream and reality, dissatisfaction with the existing and the expression of the positive principle through the images of the ideal, the desired are another major feature of the romantic method.

The advancement of the subjective factor is one of the defining differences between romanticism and realism. Romanticism "hypertrophied the individual, the individual, and endowed his inner world with universality, tearing him away from the objective world," writes the Soviet literary critic B. Suchkov

However, one should not elevate the subjectivity of the romantic method to an absolute and deny its ability to generalize and typify, that is, ultimately, to objectively reflect reality. Significant in this respect is the very interest of romantics in history. “Romanticism not only reflected the changes that took place in the public mind after the revolution. Feeling and conveying the mobility of life, its variability, as well as the mobility of human feelings that change with the changes taking place in the world, romanticism inevitably resorted to history in defining and understanding the prospects of social progress. "

The setting, the background of the action, appear in a bright and new way in romantic art, making up, in particular, a very important expressive element of the musical image for many romantic composers, starting with Hoffmann, Schubert and Weber.

The conflicting perception of the world by romantics finds expression in the principle of polar antitheses, or "double world". It is expressed in the polarity, two-dimensionality of dramatic contrasts (the real is the fantastic, the person is the world around him), in the sharp comparison of the aesthetic categories (the sublime and the everyday, the beautiful and the terrible, the tragic and the comic, etc.). It is necessary to emphasize the antinomies of romantic aesthetics itself, in which not only deliberate antitheses operate, but also internal contradictions - contradictions between its materialistic and idealistic elements. I mean, on the one hand, the sensualism of romantics, attention to the sensual-material concreteness of the world (this is strongly expressed in music), and on the other hand, the striving for some ideal absolute, abstract categories - “eternal humanity” (Wagner), “eternal femininity "(Sheet). Romantics strive to reflect the concreteness, individual originality of life phenomena and at the same time their "absolute" essence, often understood in an abstract-idealistic sense. The latter is especially characteristic of literary romanticism and its theory. Life, nature are presented here as a reflection of the "infinite", the fullness of which can only be guessed by the inspired feeling of the poet.

The theoretical philosophers of romanticism consider music to be the most romantic of all arts precisely because, in their opinion, it “has as its subject only the infinite” 1. Philosophy, literature and music, as never before, have united among themselves (a vivid example of this is the work of Wagner). Music took one of the leading places in the aesthetic concepts of such idealist philosophers as Schelling, the Schlegel brothers, Schopenhauer2. However, if literary and philosophical romanticism was to the greatest extent affected by the idealistic theory of art as a reflection of the “infinite”, “divine”, “absolute”, in music we will find, on the contrary, the objectivity of the “image” unprecedented before the romantic era, determined by the characteristic, sound-painting brilliance of images ... The approach to music as a "sensible realization of thought" 3 is at the heart of Wagner's aesthetic propositions, who, in spite of his literary predecessors, affirms the sensual concreteness of the musical image.

In assessing life phenomena, romantics are characterized by hyperbolization, which is expressed in the sharpening of contrasts, in a gravitation towards the exceptional, the unusual. “The commonplace is the death of art,” proclaims Hugo. However, in contrast to this, another romantic, Schubert, speaks in his music about "man as he is." Therefore, summarizing, it is necessary to distinguish at least two types of romantic hero. One of them is an exceptional hero, towering above ordinary people, an internally divided tragic thinker, often coming into music from fear; literary works or epics: Faust, Manfred, Childe Harold, Wotan. It is characteristic of mature and especially late musical romanticism (Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner). The other is a simple person, deeply feeling life, closely connected with the life and nature of his native land. Such is the hero of Schubert, Mendelssohn, partly Schumann, Brahms. Here romantic affectation is contrasted with sincerity, simplicity, naturalness.

Equally different is the embodiment of nature, its very understanding in romantic art, which devoted a great deal of attention to the theme of nature in its cosmic, natural-philosophical, and, on the other hand, lyrical aspect. Nature is majestic and fantastic in the works of Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner and intimate, intimate in Schubert's vocal cycles or in Schumann's miniatures. These differences are also manifested in the musical language: the song of Schubert and the pathetically upbeat, oratory melodies of Liszt or Wagner.

But no matter how different the types of heroes, the range of images, language, in general, romantic art is distinguished by special attention to the personality, a new approach to it. The problem of personality in its conflict with the environment is fundamental to romanticism. This is precisely what Gorky emphasizes when he says that the main theme of 19th century literature was "personality in its opposition to society, state, nature", "the drama of a person for whom life seems cramped." Belinsky writes about the same in connection with Byron: "This is a human personality, revolted against the common and, in its proud rebellion, leaning on itself." The romantics expressed with great dramatic force the process of alienation of the human person in bourgeois society. Romanticism illuminated new aspects of the human psyche. He embodied the personality in the most intimate, psychologically multifaceted manifestations. A man from romantics, due to the disclosure of his individuality, appears more complex and contradictory than in the art of classicism.

Romantic art generalized many typical phenomena of its era, especially in the field of human spiritual life. In different versions and solutions, the “confession of the son of the century” is embodied in romantic literature and music - sometimes elegiac, like in Musset, sometimes heightened to the grotesque (Berlioz), sometimes philosophical (Liszt, Wagner), sometimes passionately rebellious (Schumann) or modest and at the same time tragic (Schubert). But in each of them there is a leitmotif of unfulfilled aspirations, "the longing of human desires," as Wagner said, caused by the rejection of bourgeois reality and the thirst for "true humanity." The lyrical drama of the personality, in essence, turns into a social theme.

The central point in romantic aesthetics was the idea of a synthesis of arts, which played a huge positive role in the development of artistic thinking. In contrast to classicist aesthetics, romantics argue that not only are there no impassable boundaries between the arts, but, on the contrary, there are deep connections and commonality. “The aesthetics of one art is the aesthetics of another; only the material is different, ”wrote Schumann4. He saw in F. Rückert "the greatest musician of word and thought" and strove in his songs to "convey the thoughts of the poem almost literally" 2. In his piano cycles, Schumann introduced not only the spirit of romantic poetry, but also forms, compositional techniques - contrasts, interruption of narrative plans, characteristic of Hoffmann's novellas. II, on the contrary, in the literary works of Hoffmann one can feel “the birth of poetry from the spirit of music” 3.

Romantics of different directions come to the idea of synthesis of arts from opposite positions. For some, mainly philosophers and theorists of romanticism, it arises on an idealistic basis, on the idea of art as an expression of the universe, the absolute, that is, a certain unified and infinite essence of the world. For others, the idea of synthesis arises as a result of the desire to expand the boundaries of the content of an artistic image, to reflect life in all its multifaceted manifestations, that is, in essence, on a real basis. This is the position, the creative practice of the greatest artists of the era. Putting forward the well-known thesis about the theater as a "concentrated mirror of life", Hugo asserted: "Everything that exists in history, in life, in a person must and can find its reflection in him (in the theater - N.N.), but only with the help of a magic wand of art. "

The idea of a synthesis of arts is closely related to the interpenetration of various genres — epic, drama, lyricism — and aesthetic categories (sublime, comic, etc.). The ideal of modern literature is "drama, fusing in one breath the grotesque and the sublime, the terrible and the buffoonery, tragedy and comedy."

In music, the idea of a synthesis of arts was developed especially actively and consistently in the field of opera. This idea is the basis of the aesthetics of the creators of the German romantic opera - Hoffmann and Weber, the reform of Wagner's musical drama. On the same basis (synthesis of arts), the program music of the romantics developed, such a major achievement of the musical culture of the 19th century as the program symphonism.

Thanks to this synthesis, the expressive sphere of music itself has expanded and enriched. For the premise of the primacy of the word, poetry in a synthetic work by no means leads to a secondary, complementary function of music. On the contrary, in the works of Weber, Wagner, Berlioz, Liszt and Schumann, music was the most powerful and effective factor, capable in its own way, in its "natural" forms, to embody what literature and painting bring with it. "Music is the sensory realization of thought" - this thesis of Wagner has a broad meaning. Here we come to the problem of s and n-thesis of the second order, the synthesis of the internal, based on a new quality of musical imagery in romantic art. With their creativity, romantics have shown that music itself, expanding its aesthetic boundaries, is able to embody not only a generalized feeling, mood, idea, but also to "translate" into its own language with minimal help of words or even without it, images of literature and painting, to recreate the development of literary plot, be colorful, picturesque and picturesque, capable of creating a vivid characteristic, a portrait "sketch" (remember the amazing accuracy of Schumann's musical portraits) and at the same time not lose its fundamental property of expressing feelings.

This was realized not only by great musicians, but also by writers of that era. Noting the unlimited possibilities of music in revealing the human psyche, Georges Sand, for example, wrote that music “recreates even the appearance of things, without falling into petty sound effects, or into a narrow imitation of the noises of reality” i. The desire to speak and paint with music was the main thing for the creator of the romantic programmatic symphony of Berlioz, about which Sollertinsky said so vividly: “Shakespeare, Goethe, Byron, street battles, orgies of bandits, philosophical monologues of a lonely thinker, vicissitudes of a secular love story, storms and thunderstorms, exuberant fun carnival crowd, performances of farce comedians, funerals of heroes of the revolution, burial orations full of pathos - all this Berlioz seeks to translate into the language of music. " At the same time, Berlioz did not attach such a decisive importance to the word, as it might seem at first glance. “I don’t believe that in terms of the strength and power of expressiveness, such arts as painting and even poetry could be equal to music!” - said the composer3. Without this inner synthesis of musical, literary and pictorial principles, the musical work itself would not have been Liszt's programmatic symphony, his philosophical musical poem.

The synthesis of expressive and pictorial principles, new in comparison with the classical style, appears in musical romanticism at all its stages as one of the specific features. In Schubert's songs, the piano part creates the mood and "outlines" the setting of the action, using the possibilities of musical painting and sound painting. Vivid examples of this are "Margarita at the Spinning Wheel", "Forest Tsar", many of the songs from "The Beautiful Miller Woman", "Winter Road". One of the most striking examples of precise and laconic sound writing is the piano part of The Double. Picture narrative is characteristic of Schubert's instrumental music, especially his symphony in C major, sonata in B major, fantasy “The Wanderer”. Schumann's piano music is permeated with a fine "soundtrack of moods"; it is no coincidence that Stasov saw him as a brilliant portrait painter.

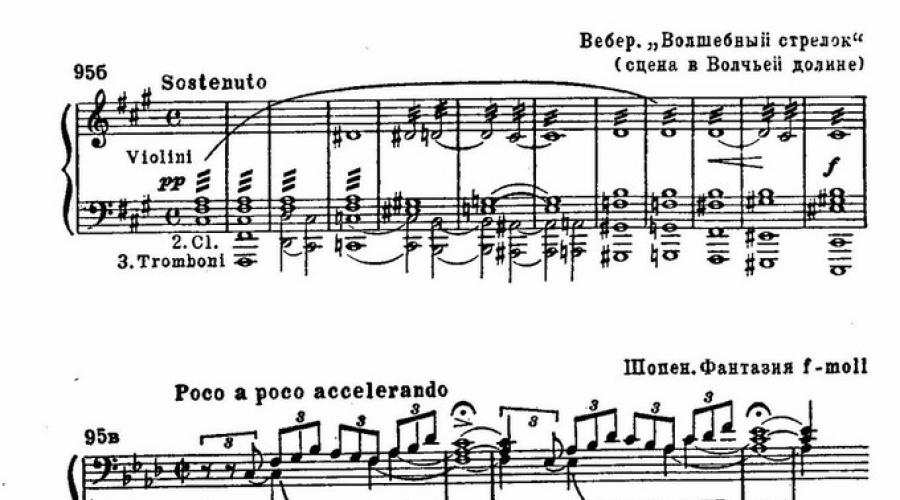

Chopin, like Schubert, who is alien to the literary program, in his ballads and f-moll fantasies creates a new type of instrumental drama, which reflects the multifaceted content, the dramatic action and the picturesque image inherent in a literary ballad.

On the basis of the drama of antitheses, free and synthetic musical forms arise, characterized by the isolation of contrasting sections within a one-part composition and continuity, the unity of the general line of ideological-figurative development.

It is, in essence, about the romantic qualities of sonata drama, a new understanding and application of its dialectical possibilities. In addition to these features, it is important here to emphasize the romantic variability of the image, its transformation. The dialectical contrasts of sonata drama acquire a new meaning among romantics. They reveal the duality of the romantic worldview, the above-mentioned principle of "double world". This finds expression in the polarity of contrasts, often created by transforming one image (for example, the single substance of the Faustian and Mephistophelian principles in Liszt). Here the factor of a sharp leap, a sudden change (even distortion) of the entire essence of the image, and not the regularity of its development and change, due to the growth of its qualities in the process of interaction of contradictory principles, as in the classics, and above all in Beethoven, is at work.

The conflict drama of romantics is characterized by its own, which has become typical, direction of the development of images - an unprecedented dynamic growth of a light lyrical image (side part) and a subsequent dramatic breakdown, a sudden interruption of the line of its development by the invasion of a formidable, tragic beginning. The typicality of this "situation" becomes obvious if we recall Schubert's symphony in h-minor, Chopin's sonata in b-minor, especially his ballads, the most dramatic works of Tchaikovsky, with renewed vigor as a realist artist who embodied the idea of a conflict between dream and reality, the tragedy of unfulfilled aspirations in conditions of a cruel reality hostile to man. Of course, one of the types of romantic drama is highlighted here, but the view is very significant and typical.

Another type of drama "- evolutionary - is associated with the romantics with a subtle nuance of the image, the disclosure of its multifaceted psychological shades, details. The main principle of development here is the melodic, harmonic, timbre variation, which does not change the essence of the image, the nature of its genre, but showing deep, outwardly barely perceptible processes of mental life, their constant movement, changes, transitions - this principle is the basis of the song symphonism born by Schubert with its lyrical nature.

The originality of the Schubert method was well defined by Asafiev: “In contrast to the dramatically dramatic development, there are those works (symphonies, sonatas, overtures, symphonic poems) in which a widely developed lyrical song line (not a general theme, but a line) generalizes and smooths out the constructive sections of the sonata-symphonic allegro. Undulating ups and downs, dynamic gradations, "swelling" and thinning of tissue - in a word, the manifestation of organic life in this kind of "song" sonatas prevails over oratorical pathos, over sudden contrasts, over dramatic dialogue and rapid disclosure of ideas. Schubert's Big B-clert "Sonata is a typical example of this trend."

Not all essential features of the romantic method and aesthetics can be found in every art form.

If we talk about music, then the most direct expression of romantic aesthetics was in opera, as a genre especially closely associated with literature. Here, such specific ideas of romanticism as the ideas of fate, redemption, overcoming the curse that gravitates over the hero, the power of selfless love ("Freischutz", "The Flying Dutchman", "Tannhäuser") are developed. The opera reflects the very plot basis of romantic literature, the opposition of the real and the fantastic worlds. It is here that the fiction inherent in romantic art, the elements of subjective idealism inherent in literary romanticism, are especially manifested. At the same time, for the first time, the poetry of the folk-national character, cultivated by romantics, flourishes so brightly in the opera.

In instrumental music, a romantic approach to reality is manifested, bypassing the plot (if it is a non-programmed composition), B the general ideological concept of the work, in the nature of its drama, embodied emotions, in the peculiarities of the psychological structure of images. The emotional and psychological tone of romantic music is distinguished by a complex and changeable range of shades, heightened expression, and the unique brightness of each experienced moment. This is embodied in the expansion and individualization of the intonational sphere of romantic melody, in the sharpening of the colorful and expressive functions of harmony. Inexhaustible discoveries of romantics in the field of orchestra, instrumental timbres.

Expressive means, the musical "speech" itself and its individual components, acquire an independent, brightly individual, and sometimes exaggerated development among romantics1. The importance of the phonism itself, the brilliance, the characteristic sound, especially in the field of harmonic and textured-timbre means, is extremely increasing. There are notions of not only a leitmotif, but also leitharmonies (for example, Wagner's stristan chord), leittembra (one of the striking examples is Berlioz's Harold in Italy symphony).

The proportional relationship of elements of the musical language observed in the classical style is giving way to a tendency towards autonomy (this tendency will be exaggerated in the music of the 20th century). On the other hand, among romantics, synthesis is intensifying - the connection between the components of the whole, mutual enrichment, and the mutual influence of expressive means. New types of melodies emerge, born of harmony, and, on the contrary, there is a melodization of harmony, its saturation with non-chord tones, exacerbating melodic gravities. A classic example of a mutually enriching synthesis of melody and harmony is Chopin's style, about which, to paraphrase Rolland's words about Beethoven, we can say that this is the absolute of melody, filled to the brim with harmony.

The interaction of opposing tendencies (autonomization and synthesis) encompasses all spheres - both the musical language and the form of romantics, who created free and synthetic forms on the basis of sonata-based Liubi.

Comparing musical romanticism with literary romanticism in their meaning for our time, it is important to emphasize the special vitality, immortality of the former. After all, romanticism is especially strong in expressing the richness of emotional life, and this is precisely what music is most subject to. That is why the differentiation of romanticism not only by trends and national schools, but also by types of arts is an important methodological moment in revealing the problem of romanticism and in its assessment.

Size: px

Start showing from page:

Transcript

1 PROGRAM - MINIMUM of the candidate exam in the specialty "Musical art" in art history Introduction The program involves testing the knowledge of graduate students and applicants for a Ph.D. degree regarding the achievements and problems of modern musicology, in-depth knowledge of the theory and history of music, orientation in the problems of modern musicology, mastering the skills of independent analysis and systematization of the material, mastering the methods of research work and the skills of scientific thinking and scientific generalization. The candidate minimum is designed for graduates of conservatories with basic education. An important place in the training of scientific and creative personnel is given to acquaintance with the problems of modern musicology (including interdisciplinary), in-depth study of the history and theory of music, including such disciplines as the analysis of musical forms, harmony, polyphony, the history of domestic and foreign music. A worthy place in the program is given to the problems of creating, preserving and distributing music, the issues of profiling scientific research of graduate students (applicants), their scientific views and interests related to the topic of the dissertation. Postgraduate students (applicants) who pass the exam in this specialty are also required to master special concepts of musicology, which make it possible to use concepts and provisions that are new for them in scientific and creative activities. An important factor in the requirements is the mastery of modern research technologies, the ability and skills to use theoretical material in practical (performing, pedagogical, scientific) activities. the factor of requirements is the mastery of modern research technologies, the ability and skills to use theoretical material in practical (performing, pedagogical, scientific) activities. The program was developed by the Astrakhan Conservatory on the basis of the minimum program of the Moscow State Tchaikovsky Conservatory, approved by the expert council of the Higher Attestation Commission of the Russian Ministry of Education for Philology and Art Criticism. QUESTIONS TO THE EXAM: 1. Theory of musical intonation. 2. Classical style in 18th century music. 3. Theory of musical drama. 4. Musical Baroque. 5. Methodology and theory of folklore.

2 6. Romanticism. Its general and musical aesthetics. 7. Genre in music. 8. Artistic and stylistic processes in Western European music of the second half of the 19th century. 9. Style in music. Polystylistics. 10. Mozartianism in the music of the XIX and XX centuries. 11. Theme and thematicism in music. 12. Imitation forms of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. 13. Fugue: concept, genesis, typology of form. 14. Traditions of Mussorgsky in Russian music of the twentieth century. 15. Ostinate and Ostinate Forms in Music. 16. Mythopoetics of Rimsky-Korsakov's operatic creativity. 17. Musical rhetoric and its manifestation in the music of the XIX and XX centuries. 18. Style processes in musical art at the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. 19. Modality. Modus. Modal technique. Modal music of the Middle Ages and the twentieth century. 20. "Faustian" theme in the music of the XIX and XX centuries. 21. Series. Serial equipment. Seriality. 22. Music of the twentieth century in the light of the ideas of the synthesis of arts. 23. The genre of opera and its typology. 24. The genre of the symphony and its typology. 25. Expressionism in music. 26. Theory of functions in musical form and in harmony. 27. Stylish processes in Russian music of the second half of the twentieth century. 28. Characteristic features of the sound organization of the music of the twentieth century. 29. Artistic trends in Russian music of the ies of the twentieth century. 30. Harmony in 19th century music. 31. Shostakovich in the context of the musical culture of the twentieth century. 32. Modern musical theoretical systems. 33. The work of I.S. Bach and its historical significance. 34. The problem of classification of chord material in modern musical theories. 35. Symphony in contemporary Russian music. 36. Problems of tonality in modern musicology. 37. Stravinsky in the context of the era. 38. Folklorism in the music of the twentieth century. 39. Word and music. 40. The main trends in Russian music of the XIX century.

3 REFERENCES: Recommended basic literature 1. Alshvang А.А. Selected works in 2 vols. M., 1964, Alshvang A.A. Tchaikovsky. M., Antique aesthetics. Introductory sketch and collection of texts by A.F. Losev. M., Anton Webern. Lectures on music. Letters. M., Aranovsky M.G. Musical text: structure, properties. M., Aranovsky M.G. Thinking, language, semantics. // Problems of Musical Thinking. M., Aranovsky M.G. Symphonic quest. L., Asafiev B.V. Selected works, T. M., Asafiev B.V. A book about Stravinsky. L., Asafiev B.V. Musical form as a process, Vol. 12 (). L., Asafiev B.V. Russian music of the 19th and early 20th centuries. L., Asafiev B.V. Symphonic Etudes. L., Aslanishvili Sh. Principles of shaping in fugues by J.S.Bach. Tbilisi, Balakirev M.A. Memories. Letters. L., Balakirev M.A. Research. Articles. L., Balakirev M.V. and V.V. Stasov. Correspondence. M., 1970, Barenboim L.A. A.G. Rubinstein. L., 1957, Barsova I.L. Essays on the history of score notation (XVI first half of the XVIII century). M., Bela Bartok. Sat Articles. M., Belyaev V.M. Mussorgsky. Scriabin. Stravinsky. M., Bershadskaya T.S. Harmony lectures. L., Bobrovsky V.P. On the variability of the functions of the musical form. M., Bobrovsky V.P. The functional foundations of the musical form. M., Bogatyrev S.S. Double canon. M.L., Bogatyrev S.S. Reversible counterpoint. M. L., Borodin A. P. Letters. M., Vasina-Grossman V.A. Russian classical romance. M., Volman B.L. Russian printed sheet music of the 18th century. L., Memories of Rachmaninoff. In 2 vols. M., Vygotsky L.S. Psychology of art. M., Glazunov A.K. Musical heritage. In 2 vols. L., 1959, 1960.

4 32. Glinka M.I. Literary heritage. M., 1973, 1975, Glinka M.I. Collection of materials and articles / Ed. Livanovoy T.M. - L., Gnesin M. Thoughts and memories of N.A. Rimsky-Korsakov. M., Gozenpud A.A. Musical theater in Russia. From the origins to Glinka. L., Gozenpud A.A. N.A. Rimsky-Korsakov. Themes and ideas of his operatic creativity. 37. Gozenpud A.A. Russian Opera House of the 19th and early 20th centuries. L., Grigoriev S.S. Theoretical course of harmony. M., Gruber R.I. The history of musical culture. Volume 1 2.M. L., Gulyanitskaya N.S. An introduction to modern harmony. M., Danilevich L. The last operas by Rimsky-Korsakov. M., Dargomyzhsky A.S. Autobiography. Letters. Memories. Pg., Dargomyzhsky A.S. Selected letters. M., Dianin S.A. Borodin. M., Diletskiy N.P. The idea of the Musiki grammar. M., Dmitriev A. Polyphony as a factor of shaping. L., Documents of the life and work of Johann Sebastian Bach. / Comp. H.- J. Schulze; per. with him. and comments. V.A. Erokhin. M., Dolzhansky A.N. On the modal basis of Shostakovich's works. (1947) // Features of D. D. Shostakovich's style. M., Druskin M.S. About Western European music of the twentieth century. M., Evdokimova Yu.K. History of polyphony. Issues I, II-a. M., 1983, Evdokimova Yu.K., Simakova N.A. Renaissance music (cantus firmus and work with it). M., Evseev S. Russian folk polyphony. M., Zhitomirsky D.V. Tchaikovsky's ballets. M., Zaderatsky V. Polyphonic thinking of I. Stravinsky. M., Zaderatsky V. Polyphony in D. Shostakovich's instrumental works. M., Zakharova O. Musical rhetoric. M., Ivanov, Boretskiy M.V. Musical and historical reader. Issue 1-2. M., History of polyphony: in 7 issues. You 2. Dubrovskaya T.N. M., History of Russian Music in Materials / Ed. K.A. Kuznetsova. M., History of Russian Music. In 10 volumes. M.,

5 61. L. P. Kazantseva Author in musical content. M., Kazantseva L.P. Foundations of the theory of musical content. Astrakhan, Kandinsky A.I. From the history of Russian symphonism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries // From the history of Russian and Soviet music, vol. 1.M., Kandinsky A.I. Monuments of Russian musical culture (choral works a capella by Rachmaninoff) // Soviet music, 1968, Karatygin V.G. Selected articles. M.L., Katuar G.L. Theoretical course of harmony, part 1 2. M., Keldysh Yu.V. Essays and studies on the history of Russian music. M., Kirillina L.V. Classical style in music of the 18th early 19th centuries: 69. The identity of the era and musical practice. M., Kirnarskaya D.K. Musical perception. M., Claude Debussy. Articles, reviews, conversations. / Per. from French M. L., Kogan G. Questions of pianism. M., Kon Yu. To the question of the concept of "musical language". // From Lully to the present day. M., Konen V.D. Theater and symphony. M., Korchinsky E.N. On the question of the theory of canonical imitation. L., Korykhalova N.P. Interpretation of music. L., Kuznetsov I.K. Theoretical foundations of polyphony of the twentieth century. M., Course E. Fundamentals of linear counterpoint. M., Kurt E. Romantic harmony and its crisis in "Tristan" by Wagner, M., Kushnarev Kh.S. Questions of the history and theory of Armenian monodic music. L., Kushnarev Kh.S. About polyphony. M., Cui Ts. Selected articles. L., Lavrent'eva I.V. Vocal forms in the analysis of musical works. M., Laroche G.A. Selected articles. In 5th issue. L., Levaya T. Russian music of the late XIX - early XX century in the artistic context of the 86. era. M., Livanova T.N. Bach's musical drama and its historical connections. M.L., Livanova T.N., Protopopov V.V. M. I. Glinka, T. M.,

6 89. Lobanova M. Western European Musical Baroque: Problems of Aesthetics and Poetics. M., Losev A.F. On the concept of artistic canon // The problem of canon in ancient and medieval art of Asia and Africa. M., Losev A.F., Shestakov V.P. History of aesthetic categories. M., Lotman Yu.M. Canonical art as an information paradox. // The problem of the canon in the ancient and medieval art of Asia and Africa. M., Lyadov An.K. Life. Portrait. Creation. Pg Mazel L.A. Music analysis questions. M., Mazel L.A. About the melody. M., Mazel L.A. Problems of classical harmony. M., Mazel L.A., Zukkerman V.A. Analysis of musical works. M., Medushevsky V.V. The intonational form of music. M., Medushevsky V.V. Musical style as a semiotic object. // CM Medushevsky V.V. On the patterns and means of artistic influence of music. M., Medtner N. Muse and Fashion. Paris, 1935, reprinted by Medtner N. Letters. M., Medtner N. Articles. Materials. Memories / Comp. Z. Apetyan. M., Milka A. Theoretical foundations of functionality. L., Mikhailov M.K. Style in music. L., Music and Musical Life of Old Russia / Ed. Asafiev. L. Musical culture of the ancient world / Ed. R.I. Gruber. L., Musical aesthetics of Germany in the XIX century. / Comp. Al.V. Mikhailov. In 2 vols. M., Musical aesthetics of the Western European Middle Ages and Renaissance. Compiled by V.P. Shestakov. M., Musical aesthetics of France in the XIX century. M., Tchaikovsky's Musical Heritage. M., Musical content: science and pedagogy. Ufa, Mussorgsky M.P. Literary heritage. M., Muller T. Polyphony. M., Myaskovsky N. Musical-critical articles: in 2 vols. M., Myasoedov A.N. About the harmony of classical music (the roots of national identity). M., 1998.

7 117. Nazaikinsky E.V. The logic of musical composition. M., Nazaikinsky E.V. On the psychology of musical perception. M., Nikolaeva N.S. "Rhine Gold" is the prologue of Wagner's concept of the universe. // 120. Problems of romantic music of the XIX century. M., Nikolaeva N.S. Symphonies by Tchaikovsky. M., Nosina V.B. The symbolism of JS Bach's music and its interpretation in the "Well 123. Tempered Clavier". M., About Rachmaninoff's symphonism and his poem "Bells" // Soviet music, 1973, 4, 6, Odoevsky V.F. Musical and literary heritage. M., Pavchinsky S.E. Scriabin's works of the late period. M., Paisov Yu.I. Politonality in the works of Soviet and foreign composers of the twentieth century. M., In memory of S.I. Taneev. M., Prout E. Fuga. M., Protopopov V.V. "Ivan Susanin" by Glinka. M., Protopopov V.V. Essays from the history of instrumental forms of the 16th early 19th century. M., Protopopov V.V. The principles of the musical form of J.S.Bach. M., Protopopov V.V., Tumanina N.V. Tchaikovsky's operatic creativity. M., Rabinovich A.S. Russian opera before Glinka. M., Rachmaninov S.V. Literary heritage / Comp. Z. Apetyan M., Riemann H. Simplified harmony or the doctrine of the tonal functions of chords. M., Rimsky-Korsakov A.N. N.A. Rimsky-Korsakov. Life and creation. M., Rimsky-Korsakov N.A. Memories of V.V. Yastrebtseva. L., 1959, Rimsky-Korsakov N.A. Literary heritage. T M., Rimsky-Korsakov N.A. Practical textbook of harmony. Complete Works, v. Iv. M., Richard Wagner. Selected works. M., Rovenko A. Practical foundations of straight simulation polyphony. M., Romain Rolland. Moose. historical heritage. Vyp M., Rubinstein A.G. Literary heritage. T. 1, 2.M., 1983, 1984.

8 145. Russian book about Bach / Ed. T.N. Livanova, V.V. Protopopova. M., Russian music and the twentieth century. M., Russian artistic culture of the late 19th early 20th century. Book. 1, 3.M., 1969, Ruchevskaya E.A. Functions of the theme music. L., Savenko S.I. I.F. Stravinsky. M., Saponov M.L. Minstrels: Essays on the Musical Culture of the Western Middle Ages. Moscow: Prest, Simakova N.A. Vocal genres of the Renaissance. M., Skrebkov S.S. Polyphony tutorial. Ed. 4. M., Skrebkov S.S. Artistic principles of musical styles. M., Skrebkov S.S. Artistic principles of musical styles. M., Skrebkova-Filatova M.S. Texture in Music: Artistic Possibilities, Structure, Functions. M., Skryabin A.N. On the 25th anniversary of his death. M., Skryabin A.N. Letters. M., Skryabin A.N. Sat. Art. M., Smirnov M.A. The emotional world of music. M., Sokolov O. On the problem of the typology of muses. genres. // Problems of 20th century music. Gorky, A.A. Solovtsov The life and work of Rimsky-Korsakov. M., Sokhor A. Questions of sociology and aesthetics of music. Part 2. L., Sokhor A. Theory of muses. genres: tasks and prospects. // Theoretical problems of musical forms and genres. M., Sposobin I.V. Lectures on the course of harmony. M., Stasov V.V. Articles. About music. In 5 issues. M., Stravinsky I.F. Dialogues. M., Stravinsky I.F. Correspondence with Russian correspondents. T / Red-sost. V.P. Varunts. M., Stravinsky I.F. Digest of articles. M., Stravinsky I.F. Chronicle of my life. M., Taneev S.I. Analysis of modulations in Beethoven's sonatas // Russian book about Beethoven. M., Taneev S.I. From the scientific and pedagogical heritage. M., Taneev S.I. Materials and documents. M., Taneev S.I. A movable counterpoint to austere writing. M., Taneev S.I. Teaching about the canon. M., Tarakanov M.E. Alban Berg Musical Theater. M., 1976.

9 176. Tarakanov M.E. New tonality in the music of the twentieth century // Problems of Musical Science. M., Tarakanov M.E. New images, new means // Soviet music, 1966, 1, M.E. Tarakanov. Creative work of Rodion Shchedrin. M., Telin Yu.N. Harmony. Theoretical course. M., Timofeev N.A. Transformability of simple canons of strict writing. M., Tumanina N.V. Tchaikovsky. In 2 vols. M., 1962, Tyulin Yu.N. The art of counterpoint. M., Tyulin Yu.N. On the origin and initial development of harmony in folk music // Questions of musical science. M., Tyulin Yu.N. Modern harmony and its historical origin / 1963 /. // Theoretical problems of 20th century music. M., Tyulin Yu.N. The doctrine of harmony (1937). M., Ferenc Liszt. Berlioz and his symphony "Harold" // Liszt F. Izbr. articles. M., Ferman V.E. Opera theatre. M., Fried E.L. Past, present and future in "Khovanshchina" by Mussorgsky. L., Kholopov Yu.N. Changing and unchanging in the evolution of the muses. thinking. // Problems of tradition and innovation in contemporary music. M., Kholopov Yu.N. Lada Shostakovich // Dedicated to Shostakovich. M., Kholopov Yu.N. About three foreign systems of harmony // Music and modernity. M., Kholopov Yu.N. Structural levels of harmony // Musica theorica, 6, MGK. M., 2000 (manuscript) Kholopova V.N. Music as an art form. SPb., Kholopova V.N. Musical themes. M., Kholopova V.N. Russian musical rhythm. M., Kholopova V.N. Texture. M., Tsukkerman V.A. "Kamarinskaya" by Glinka and its traditions in Russian music. M., Tsukkerman V.A. Analysis of musical works: Variational form. M., Tsukkerman V.A. Analysis of musical works: General principles of development and shaping in music, simple forms. M., 1980.

10 200. Tsuckerman V.A. Expressive means of Tchaikovsky's lyrics. M., Tsukkerman V.A. Musical theoretical sketches and studies. M., 1970, Tsukkerman V.A. Musical theoretical sketches and studies. M., 1970., no. II. M., Tsukkerman V.A. Musical genres and foundations of musical forms. M., Tsukkerman V.A. Liszt's Sonata in B minor. M., Tchaikovsky M.I. The life of PI Tchaikovsky. M., Tchaikovsky P.I. and Taneev S.I. Letters. M., Tchaikovsky P.I. Literary heritage. T M., Tchaikovsky P.I. A guide to the practical study of harmony / 1872 /, Complete collection of works, vol. Iii-a. M., Cherednichenko T.V. On the problem of artistic value in music. // Problems of Musical Science. Issue 5. M., Chernova T.Yu. Drama in instrumental music. M., Chugaev A. Structural features of Bach's clavier fugues. M., Shakhnazarova N.G. Music of the East and Music of the West. M., Etinger M.A. Early classical harmony. M., Yuzhak K.I. A theoretical sketch of the polyphony of free writing. L., Yavorskiy B.L. The main elements of music // Art, 1923, Yavorsky B.L. The structure of musical speech. Ch M., Yakupov A.N. Theoretical problems of musical communication. M., Das Musikwerk. Eine Beispielsammlung zur Musikgeschichte. Hrsg. von K.G. Fellerer. Koln: Arno Volk Denkmaler der Tonkunst in Osterreich (DTO) [Multivolume Series "Monuments of Musical Art in Austria"] Denkmaler Deutscher Tonkunst (DDT) [Multivolume Series "Monuments of German Art"].

Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation PROGRAM - MINIMUM of the candidate exam in the specialty 17.00.02 "Musical art" in art history The minimum program contains 19 pages.

Introduction The program of the candidate exam in the specialty 17.00.02 musical art involves finding out the knowledge of graduate students and applicants for the degree of candidate of sciences about achievements and problems

Approved by the decision of the Academic Council of the Krasnodar State Institute of Culture dated March 29, 2016, minutes 3 ENTRANCE TEST PROGRAM for applicants

The content of the entrance exam in the specialty 50.06.01 Art history 1. Interview on the topic of the abstract 2. Answering questions on the history and theory of music Requirements for the scientific abstract Introductory

QUESTIONS FOR THE CANDIDATE EXAM ON SPECIALTIES Direction of study 50.06.01 "Art history" Direction (profile) "Musical art" Section 1. History of music History of Russian music

The compiler of the program: A.G. Alyabyeva, Doctor of Arts, Professor of the Department of Musicology, Composition and Methods of Music Education. The purpose of the entrance exam: assessment of the formation of the applicant

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE of the Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Murmansk State Humanitarian University" (MSHU) WORKING

EXPLANATORY NOTE Creative competition to identify certain theoretical and practical creative abilities of applicants, is held on the basis of the academy according to the program developed by the academy

Tambov Regional State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education "Tambov State Music and Pedagogical Institute named after S.V. Rachmaninov "INTRODUCTORY PROGRAM

Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education North Caucasus State Institute of Arts Executive

1 თბილისის ვანო სარაჯიშვილის სახელობის სახელმწიფო კონსერვატორია სადოქტორო პროგრამა: საშემსრულებლო ხელოვნება სპეციალობა: აკადემიური სიმღერა მისაღები გამოცდების მოთხოვნები I. სპეციალობა სოლო სიმღერა - 35-40

Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “Russian State University named after A.N. Kosygin (Technology. Design. Art) "

The content of the entrance test in the direction of 50.06.01 Art history 1. Interview on the topic of the abstract. 2. Answering questions about the history and theory of music. The form of the entrance test

MINISTRY OF CULTURE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION FEDERAL STATE BUDGETARY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF HIGHER EDUCATION "ORLOVSK STATE INSTITUTE OF CULTURE"

Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Novosibirsk State Conservatory (Academy)

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Murmansk State Humanitarian University" (MSHU) WORKING

The program was discussed and approved at a meeting of the Department of History and Theory of Music of the Tambov State Music and Pedagogical Institute named after S.V. Rachmaninov. Minutes 2 dated September 5, 2016 Developers:

2. Professional test (solfeggio, harmony) Write a two-three-part dictation (harmonic structure with melodic-developed voices, using alteration, deviations and modulations, including

Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education North Caucasus State Institute of Arts Executing Faculty Department of History and Theory

THE PROGRAM OF THE DISCIPLINE Musical literature (foreign and domestic) 2013 The program of the academic discipline was developed on the basis of the Federal State Educational Standard (hereinafter

Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Novosibirsk State Conservatory (Academy)

Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Novosibirsk State Conservatory (Academy)

The program was approved at a meeting of the Department of History and Theory of Music of the Federal Target Program, minutes 5 of 09.04.2017 This program is intended for applicants entering the postgraduate study of the Orthodox St.

MINISTRY OF CULTURE OF THE REPUBLIC OF CRIMEA STATE BUDGET EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF HIGHER EDUCATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF CRIMEA "CRIMEAN UNIVERSITY OF CULTURE, ARTS AND TOURISM"

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF THE LUGANSK PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC LUGANSK UNIVERSITY NAMED AFTER TARAS SHEVCHENKO Institute of Culture and Arts PROGRAM of the profile entrance test in the specialty "Musical

Explanatory note The work program of the subject "Music" for grades 5-7 was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Federal State Educational Standard of Basic General Education

Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Novosibirsk State Conservatory (Academy)

Department of Culture of the city of Moscow GBOUDOD of Moscow "Voronovskaya Children's Art School" Adopted by the Pedagogical Council Minutes of 2012. "Approved" by the Director of GBOUDOD (IN Gracheva) 2012 Teacher's work program

Planning music lessons. Grade 5. Theme of the Year: "Music and Literature" "Russian Classical Music School". 5. Acquaintance with large symphonic forms. 6. Expanding and deepening the presentation

Compiled by: O. Sokolova, Ph.D., Associate Professor Reviewer: V. Yu. Grigorieva, Ph.D., Associate Professor The program was approved at a meeting of the Department of History and Theory of Music FTP, minutes 1 of 01.09.2018. 2 This program

Program compiler: Program compilers: T.I. Strazhnikova, Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Musicology, Composition and Methods of Music Education. The program is designed

Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Nizhny Novgorod State Conservatory named after M.I. Glinka L.A. Ptushko HISTORY OF DOMESTIC MUSIC OF THE FIRST HALF OF THE XX CENTURY Textbook for students of musical

State Classical Academy named after Maimonides Faculty of World Musical Culture Department of Theory and History of Music Approved by: Rector of S. Maimonides prof. Sushkova-Irina Ya.I. Subject program

THE PROGRAM OF THE DISCIPLINE Musical literature (foreign and domestic) 208 The program of the academic discipline was developed on the basis of the Federal State Educational Standard (hereinafter

DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE AND TOURISM OF THE VOLOGDA REGION budgetary professional educational institution of the Vologda region "VOLOGDA REGIONAL COLLEGE OF ARTS" (BPOU VO "Vologda Regional College

Class: 6 Hours per week: Total hours: 35 I trimester. Total weeks 0.6 total lesson hours Thematic planning Subject: Music Section. "The transforming power of music" The transforming power of music as a species

Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Nizhny Novgorod State Conservatory (Academy) named after M.I. Glinka Department of Choral Conducting G.V. Suprunenko Principles of theatricalization in a modern choral

Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education North Caucasus State Institute of Arts Executive

Additional general developmental program "Performing arts (piano) preparation for the level of higher education programs of undergraduate programs, specialty programs" References 1. Alekseev

Budgetary professional educational institution of the Udmurt Republic "Republican Music College" FUNDS FOR EVALUATION MEANS CONTROL AND EVALUATION MATERIALS FOR EXAM Specialty 53.02.07

1. EXPLANATORY NOTE Admission in the direction of training 53.04.01 "Musical Instrumental Art" is carried out in the presence of higher education of any level. Applicants for training on this

Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education Moscow State Institute of Culture APPROVED BY L.S.Zorilova, Dean of the Faculty of Musical Art eighteen

Explanatory note. The work program is based on the standard program for "literacy and listening to music", Blagonravova NS. The work program is designed for grades 1-5. To the musical

Explanatory note Entrance tests in the direction of "Musical and instrumental art", profile "Piano" reveal the level of pre-university training of applicants for further improvement

Programs of additional entrance examinations of creative and (or) professional orientation according to the specialist training program: 53.05.05 Musicology Additional entrance examinations of creative

Municipal autonomous institution of additional education of the urban district "City of Kaliningrad" "Children's music school named after D.D. Shostakovich "Exam requirements for the subject" Musical

PRIVATE EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF HIGHER EDUCATION "ORTHODOX ST. TIKHONOVSK HUMANITARIAN UNIVERSITY" (PSTGU) Moscow APPROVED Vice-rector for scientific work, Archpriest. K. Polskov, Cand. Philos.

Elena Igorevna Luchina, PhD in Art History, Associate Professor of the Department of Music History Born in Karl-Marx-Stadt (Germany). Graduated from the theoretical and piano departments of the Voronezh College of Music

Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Novosibirsk State Conservatory (Academy)

Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education North Caucasus State Institute of Arts Executing Faculty