Leon battista alberti biography briefly. The doctrine of man by leon battista alberti

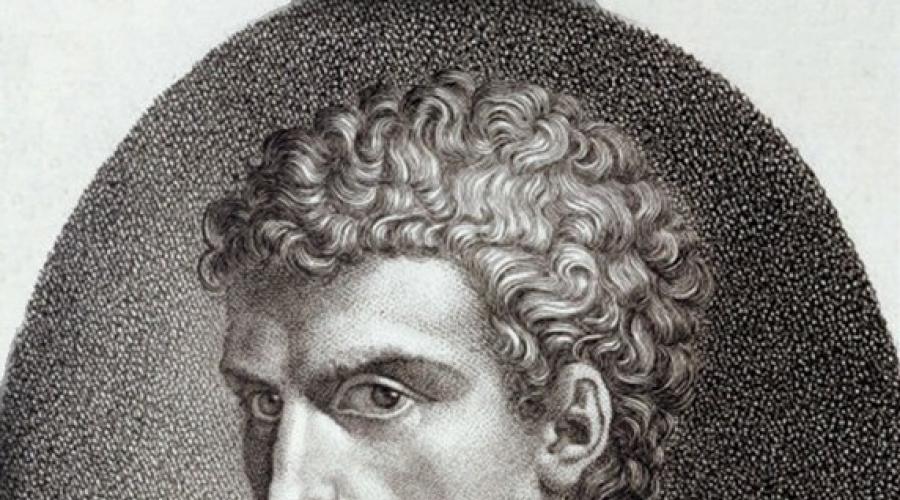

Another direction in the Italian humanism of the 15th century. was the work of Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) - an outstanding thinker and writer, art theorist and architect. Coming from a noble Florentine family in exile, Leon Battista graduated from the University of Bologna, was hired as a secretary to Cardinal Albergati, and then to the Roman Curia, where he spent more than 30 years. He owned works on ethics ("About the family", "Domostroy"), architecture ("About architecture"), cartography and mathematics. His literary talent manifested itself with particular force in a cycle of fables and allegories ("Table Conversations", "Mom, or About the Sovereign"). As a practicing architect, Alberti created several projects that laid the foundations of the Renaissance style in 15th century architecture.

In the new complex of humanities, Alberti was most attracted by ethics, aesthetics and pedagogy. Ethics for him is a "science of life", necessary for educational purposes, since it is able to answer the questions put forward by life - about the attitude to wealth, about the role of virtues in achieving happiness, about confronting Fortune. It is not by chance that the humanist writes his works on moral and didactic topics in Volgar - he intends them for numerous readers.

Alberti's humanistic concept of man is based on the philosophy of the ancients - Plato and Aristotle, Cicero and Seneca, and other thinkers. Its main thesis is harmony as an immutable law of being. It is also a harmoniously arranged space, which generates a harmonious connection between man and nature, the individual and society, the inner harmony of the individual. Inclusion in the natural world subordinates a person to the law of necessity, which creates a counterbalance to the whims of Fortune - a blind chance that can destroy his happiness, deprive him of his well-being and even life. To confront Fortune, a person must find strength in himself - they are given to him from birth. All potential human abilities Alberti unites with the capacious concept of virtu (Italian, literally - valor, ability). Upbringing and education are designed to develop in a person the natural properties of nature - the ability to cognize the world and use the knowledge gained, the will for an active, active life, the desire for good. Man is a creator by nature, his highest vocation is to be the organizer of his earthly existence. Reason and knowledge, virtue and creative work - these are the forces that help fight the vicissitudes of fate and lead to happiness. And it is in the harmony of personal and public interests, in peace of mind, in earthly glory, crowning true creativity and good deeds. Alberti's ethics were consistently secular; they were completely separated from theological issues. The humanist affirmed the ideal of an active civil life - it is in it that a person can reveal the natural properties of his nature.

One of the important forms of civic activity Alberti considered economic activity, and it is inevitably associated with hoarding. He justified the desire for enrichment, if it does not give rise to an excessive passion for acquisitiveness, because it can deprive a person of peace of mind. In relation to wealth, he calls to be guided by a reasonable measure, to see in it not an end in itself, but a means of serving society. Wealth should not deprive a person of moral perfection, on the contrary, it can become a means for fostering virtue - generosity, generosity, etc. In Alberti's pedagogical ideas, the mastery of knowledge and compulsory work play a leading role. He assigns to the family, in which he sees the main social unit, the duty to educate the younger generation in the spirit of new principles. He considers the interests of the family to be self-sufficient: one can abandon state activities and focus on economic affairs, if this will benefit the family, and this does not violate its harmony with society, since the well-being of the whole depends on the well-being of its parts. The emphasis on the family, worries about its prosperity distinguishes Alberti's ethical position from the ideas of civil humanism, with which he is related by the moral ideal of active life in society.

»The idea of a multi-alphabetic cipher.

Biography

Born in Genoa, he came from a noble Florentine family in exile in Genoa. He studied humanities in Padua and law in Bologna. In 1428 he graduated from the University of Bologna, after which he received the post of secretary from Cardinal Albergati, and in 1432 - a place in the papal chancellery, where he served for more than thirty years. In 1462 Alberti left the curia and lived in Rome until his death.

Alberti's humanistic worldview

Harmony

The multifaceted work of Leon Battista Alberti is a vivid example of the universality of the interests of the Renaissance man. Diversified and educated, he made a major contribution to the theory of art and architecture, literature and architecture, was fond of the problems of ethics and pedagogy, was engaged in mathematics and cartography. The central place in Alberti's aesthetics belongs to the doctrine of harmony as an important natural law, which a person should not only take into account in all his activities, but also extend his own creativity to different spheres of his being. The outstanding thinker and talented writer Alberti created a consistently humanistic doctrine of man, opposed by its secularity to official orthodoxy. Creation of oneself, physical perfection - become a goal, as well as spiritual.

Human

The ideal person, according to Alberti, harmoniously combines the forces of reason and will, creativity and peace of mind. He is wise, is guided in his actions by the principles of measure, has a consciousness of his own dignity. All this gives the image, created by Alberti, features of greatness. The ideal of a harmonious personality put forward by him influenced both the development of humanistic ethics and Renaissance art, including in the portrait genre. It is this type of person that is embodied in the images of painting, graphics and sculpture of Italy of that time, in the masterpieces of Antonello da Messina, Piero della Francesca, Andrea Mantegna and other major masters. Alberti wrote many of his works in Volgar, which contributed a lot to the widespread dissemination of his ideas in Italian society, including among artists.

| Nature, that is, God, has put into man an element of heaven and divine, incomparably more beautiful and noble than anything mortal. She gave him talent, the ability to learn, intelligence - divine properties, thanks to which he can explore, discern and know what to avoid and what to follow in order to preserve himself. To these great and priceless gifts, God has also put in the human soul moderation, restraint against passions and excessive desires, as well as shame, modesty and the desire to earn praise. In addition, God instilled in people the need for a strong mutual connection, which supports community, justice, justice, generosity and love, and with all this, a person can earn gratitude and praise from people, and from his creator - benevolence and mercy. God has also put into the human breast the ability to withstand every work, every misfortune, every blow of fate, to overcome all sorts of difficulties, to overcome sorrow, not to be afraid of death. He gave man strength, steadfastness, firmness, strength, contempt for insignificant trifles ... Therefore, be convinced that a person is born not to drag out a sad existence in inaction, but to work on a great and grandiose deed. By this, he can, firstly, please God and honor him and, secondly, acquire for himself the most perfect virtues and complete happiness. (Leon Battista Alberti) |

Creativity and labor

The initial premise of the humanistic concept of Alberti is the inalienable belonging of man to the natural world, which the humanist interprets from pantheistic positions as the bearer of the divine principle. A person included in the world order finds himself at the mercy of its laws - harmony and perfection. The harmony of man and nature is determined by his ability to cognize the world, to a reasonable, striving for good existence. Alberti places the responsibility for moral improvement, which has both personal and social significance, on the people themselves. The choice between good and evil depends on the free will of the person. The humanist saw the main purpose of the personality in creativity, which he understood broadly - from the labor of a humble artisan to the heights of scientific and artistic activity. Alberti especially highly appreciated the work of the architect - the organizer of people's lives, the creator of reasonable and wonderful conditions for their existence. In the creative ability of man, the humanist saw his main difference from the animal world. Labor for Alberti is not a punishment for original sin, as church morality taught, but a source of spiritual uplift, material wealth and glory. " In idleness, people become weak and insignificant”, Besides, only the life practice itself reveals the great possibilities inherent in a person. " The art of living is comprehended in deeds", - emphasized Alberti. The ideal of active life makes his ethics related to civic humanism, but there are many features in it that make it possible to characterize the teachings of Alberti as an independent direction in humanism.

A family

Alberti assigned the family an important role in the upbringing of a person who energetically multiplies his own benefits and the benefits of society and the state by honest labor. In it, he saw the basic unit of the entire system of social order. The humanist paid a lot of attention to family foundations, especially in the dialogues written in Volgar “ About family" and " Domostroy". In them, he addresses the problems of upbringing and primary education of the younger generation, solving them from a humanistic standpoint. It defines the principle of the relationship between parents and children, keeping in mind the main goal - strengthening the family, its inner harmony.

Family and community

In the economic practice of Alberti's time, family business, industrial and financial companies played an important role, in this regard, the family is considered a humanist and as the basis of economic activity. He connected the path to the prosperity and wealth of the family with the rational management of the economy, with accumulation based on the principles of thrift, zealous concern for business, and hard work. Alberti considered dishonest methods of enrichment unacceptable (partly at odds with merchant practice and mentality), because they deprive the family of a good reputation. The humanist advocated such a relationship between the individual and society, in which personal interest is consistent with the interests of other people. However, unlike the ethics of civil humanism, Alberti believed it possible in certain circumstances to put the interests of the family above the momentary public benefit. For example, he recognized as permissible the refusal from public service for the sake of focusing on economic work, since in the final analysis, as the humanist believed, the welfare of the state is based on solid material foundations of individual families.

Society

Alberti's society itself is thought of as a harmonious unity of all its layers, which should be promoted by the activities of the rulers. Pondering the conditions of achievement social harmony, Alberti in the treatise " About architecture»Draws an ideal city, beautiful in terms of rational planning and external appearance of buildings, streets, squares. The entire living environment of a person is arranged here so that it meets the needs of the individual, family, society as a whole. The city is divided into various spatial zones: in the center are the buildings of the higher magistrates and the palaces of the rulers, on the outskirts there are quarters of artisans and small merchants. The palaces of the upper strata of society are thus spatially separated from the dwellings of the poor. This urban planning principle should, according to Alberti, prevent the harmful consequences of possible popular unrest. The ideal city of Alberti, however, is characterized by the equal improvement of all its parts for the life of people of different social status and the accessibility of beautiful public buildings to all its inhabitants - schools, thermal baths, theaters.

Embodying the idea of an ideal city in word or image was one of the typical features of the Renaissance culture of Italy. The projects of such cities were paid tribute to the architect Filarete, scientist and artist Leonardo da Vinci, authors of social utopias of the 16th century. They reflect the dream of humanists about the harmony of human society, about wonderful external conditions that contribute to its stability and happiness of every person.

Moral improvement

Like many humanists, Alberti shared the idea of the possibility of providing social peace through the moral improvement of each person, the development of his active virtue and creativity. At the same time, being a thoughtful analyst of the life practice and psychology of people, he saw “ human kingdom»In all the complexity of its contradictions: refusing to be guided by reason and knowledge, people sometimes become destroyers, and not creators of harmony in the earthly world. Alberti's doubts were vividly expressed in his “ Mome" and " Table conversations”, But did not become decisive for the main line of his reflections. The ironic perception of the reality of human deeds, characteristic of these works, did not shake the deep faith of the humanist in the creative power of a person called upon to equip the world according to the laws of reason and beauty. Many of Alberti's ideas were further developed in the work of Leonardo da Vinci.

Creation

Literature

Alberti wrote his first works in the 1920s. - comedy " Philodox"(1425)," Deifyra"(1428), etc. In the 30s - early 40s. created a number of works in Latin - “ The advantages and disadvantages of scientists"(1430)," On the Right "(1437)," Pontifex"(1437); dialogues on Volgar on ethical topics - “ About family"(1434-1441)," About peace of mind"(1443).

Alberti wrote his first works in the 1920s. - comedy " Philodox"(1425)," Deifyra"(1428), etc. In the 30s - early 40s. created a number of works in Latin - “ The advantages and disadvantages of scientists"(1430)," On the Right "(1437)," Pontifex"(1437); dialogues on Volgar on ethical topics - “ About family"(1434-1441)," About peace of mind"(1443).

In the 50-60s. Alberti wrote a satirical-allegorical cycle “ Table conversations”- his main works in the field of literature, which became examples of Latin humanistic prose of the 15th century. Alberti's latest works: “ On the principles of composing codes"(Mathematical treatise, later lost) and dialogue on Volgar" Domostroy"(1470).

Alberti was one of the first to advocate the use of the Italian language in literary work. His elegies and eclogies are the first examples of these genres in Italian.

Alberti created a largely original (dating back to Plato, Aristotle, Xenophon and Cicero) concept of man, based on the idea of harmony. Alberti's ethics - secular in nature - was distinguished by attention to the problem of man's earthly existence, his moral improvement. He magnified the natural abilities of man, appreciated knowledge, creativity, and the mind of man. In the teachings of Alberti, the ideal of a harmonious personality received the most integral expression. Alberti combined all the potential abilities of a person with the concept virtu(valor, ability). It is in the power of man to reveal these natural abilities and become a full-fledged creator of his own destiny. According to Alberti, upbringing and education should develop in a person the properties of nature. Human abilities. his mind, will, courage help him to withstand the fight against the goddess of chance, Fortune. Alberti's ethical concept is full of faith in a person's ability to reasonably organize his life, family, society, and state. Alberti considered the family to be the main social unit.

Architecture

Alberti the architect had a great influence on the formation of the High Renaissance style. Following Filippo Brunelleschi, he developed antique motifs in architecture. According to his designs, the Palazzo Rucellai in Florence (1446-1451) was built, the Church of Santissima Annunziata, the facade of the Church of Santa Maria Novella (1456-1470), the churches of San Francesco in Rimini, San Sebastiano and Sant Andrea in Mantua were rebuilt - the buildings that defined the main direction in the architecture of the Quattrocento.

Alberti was also engaged in painting, tried his hand at sculpture. As the first theorist of the Italian Renaissance art, he is known for the essay “ Ten books on architecture"(De re aedificatoria) (1452), and a small Latin treatise" About the statue"(1464).

Bibliography

- Alberti Leon Battista. Ten books on architecture: In 2 volumes - M., 1935-1937.

- Alberti Leon Battista. Family books. - M .: Languages of Slavic cultures, 2008.

- Masters of arts about art. T. 2: The Renaissance / Ed. A. A. Guber, V. N. Grashchenkova. - M., 1966.

- Revyakina N.V. Italian Renaissance. Humanism of the second half of the 14th - first half of the 15th century. - Novosibirsk, 1975.

- Abramson M.L. From Dante to Alberti / Otv. ed. Corresponding Member USSR Academy of Sciences Z.V. Udaltsova. USSR Academy of Sciences. - M .: Nauka, 1979 .-- 176, p. - (From the history of world culture). - 75,000 copies(region)

- Works of Italian humanists of the Renaissance (XV century) / Ed. L. M. Bragina. - M., 1985.

- The history of culture of the countries of Western Europe in the Renaissance / Ed. L. M. Bragina. - M .: Higher school, 2001.

- V. P. Zubov Alberti's architectural theory. - SPb .: Aleteya, 2001 .-- ISBN 5-89329-450-5.

- Anikst A. Outstanding architect and art theorist // Architecture of the USSR. 1973. No. 6. S. 33-35.

- Markuson V.F. Alberti's place in the architecture of the early Renaissance // Architecture of the USSR. 1973. No. 6. S. 35-39.

- Leon Battista Alberti: Sat. articles / Otv. ed. V. N. Lazarev; Scientific Council for the History of World Culture, USSR Academy of Sciences. - M .: Nauka, 1977 .-- 192, p. - 25,000 copies.(region)

- Danilova I.E. Alberti and Florence. M., 1997. (Readings on the history and theory of culture. Issue 18. Russian State University for the Humanities. Institute of Higher Humanitarian Research). (Reprinted with attachment: Danilova IE "The fullness of times has come true ..." Reflections on art. Articles, studies, notes. M., 2004. S. 394-450).

- V.P. Zubov Alberti and the Cultural Heritage of the Past // Masters of Classical Art of the West. M., 1983.S. 5-25.

- Enenkel K. The origin of the Renaissance ideal “uomo universale”. "Autobiography" by Leon Battista Alberti // Man in the culture of the Renaissance. M., 2001.S. 79-86.

- V.P. Zubov Alberti's architectural theory. SPb., 2001.

- V.I. Pavlov L.-B. Alberti and the invention of pictorial linear perspective // Italian collection 3. SPb., 1999. S. 23-34.

- Revzina Yu. Church of San Francesco in Rimini. Architectural project in the view of Alberti and his contemporaries // Questions of art history. XI (2/97). M., 1997. S. 428-448.

- A. Renaissance in Rimini. M., 1970.

Write a review on the article "Alberti, Leon Battista"

Notes (edit)

Links

- // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - SPb. , 1890-1907.

Excerpt from Alberti, Leon Battista

- I'll let you run around the yards! He shouted.Alpatych returned to the hut and, having called the coachman, ordered him to leave. Following Alpatych and the coachman, all of Ferapontov's household went out. Seeing the smoke and even the fires of the fires, which were now visible in the beginning of dusk, the women, who had been silent until then, suddenly began to shout, looking at the fires. As if echoing them, the same cries were heard at other ends of the street. Alpatych, with the coachman shaking hands, was straightening the tangled reins and horses' trims under the canopy.

When Alpatych was driving out of the gate, he saw how ten soldiers, loudly talking, poured sacks and knapsacks with wheat flour and sunflowers in the open shop of Ferapontov. At the same time, returning from the street to the shop, Ferapontov entered. Seeing the soldier, he wanted to shout something, but suddenly stopped and, clutching a hair, burst out laughing with sobbing laughter.

- Bring everything, guys! Don't get the devils! He shouted, grabbing the bags himself and throwing them out into the street. Some of the soldiers, frightened, ran out, some continued to pour. Seeing Alpatych, Ferapontov turned to him.

- I made up my mind! Race! He shouted. - Alpatych! made up my mind! I'll ignite it myself. I made up my mind ... - Ferapontov ran into the yard.

On the street, damming it all up, soldiers were continuously walking, so that Alpatych could not pass and had to wait. The owner of Ferapontova with her children was also sitting on the cart, waiting to be able to leave.

It was already quite night. There were stars in the sky and a young moon, occasionally obscured by smoke, shone. On the descent to the Dnieper, the carts of Alpatych and the hostess, slowly moving in the ranks of soldiers and other carriages, had to stop. Not far from the crossroads at which the carts stopped, in an alley, a house and shops were on fire. The fire was already burning out. The flame either died away and was lost in the black smoke, then suddenly flared up brightly, strangely clearly illuminating the faces of the crowd of people standing at the intersection. Before the fire, black figures of people flashed, and from behind the incessant crackle of the fire, talk and shouts were heard. Alpatych, dismounted from the cart, seeing that the cart would not be allowed to pass him soon, turned into the alley to watch the fire. The soldiers were constantly darting back and forth past the fire, and Alpatych saw how two soldiers and with them a man in a frieze overcoat dragged from the fire across the street to the neighboring courtyard burning logs; others carried armfuls of hay.

Alpatych approached a large crowd of people standing opposite a high barn burning in full fire. The walls were all on fire, the back one had collapsed, the plank roof had collapsed, the beams were on fire. Obviously, the crowd was waiting for the moment when the roof collapsed. Alpatych expected the same.

- Alpatych! A familiar voice suddenly called out to the old man.

- Father, your Excellency, - answered Alpatych, instantly recognizing the voice of his young prince.

Prince Andrey, in a cloak, riding a black horse, stood behind the crowd and looked at Alpatych.

- How are you here? - he asked.

- Your ... your Excellency, - said Alpatych and sobbed ... - Yours, yours ... or have we already disappeared? Father…

- How are you here? - repeated Prince Andrey.

The flame flared up brightly at that moment and illuminated Alpatych's pale and emaciated face of his young master. Alpatych told how he was sent and how he could leave by force.

- Well, your Excellency, or are we lost? He asked again.

Prince Andrey, without answering, took out a notebook and, raising his knee, began to write in pencil on a torn sheet. He wrote to his sister:

“Smolensk is being surrendered,” he wrote. “Bald Hills will be occupied by the enemy in a week. Leave now to Moscow. Answer me as soon as you leave by sending a courier to Usvyazh. "

Having written and passed the sheet to Alpatych, he verbally conveyed to him how to arrange the departure of the prince, princess and son with a teacher, and how and where to answer him immediately. He had not yet had time to finish these orders, when the mounted staff chief, accompanied by his retinue, galloped up to him.

- Are you a colonel? - shouted the chief of staff, with a German accent, familiar to Prince Andrei's voice. - In your presence, houses are lit up, and you are standing? What does this mean? You will answer, ”shouted Berg, who was now assistant chief of staff of the left flank of the infantry forces of the first army,“ the place is very pleasant and in sight, as Berg said.

Prince Andrey looked at him and, without answering, continued, addressing Alpatych:

- So tell me that until the tenth I am waiting for an answer, and if on the tenth I do not receive the news that everyone has left, I myself will have to drop everything and go to Bald Hills.

- I, prince, only because I say, - said Berg, recognizing Prince Andrei, - that I have to obey orders, because I always do exactly ... You will excuse me, please, - Berg justified himself in some way.

Something crackled in the fire. The fire died down for a moment; black clouds of smoke poured from under the roof. Something else creaked terribly in the fire, and something huge collapsed.

- Urruru! - echoing the collapsed ceiling of the barn, from which the smell of cakes from burnt bread smelled, the crowd roared. The flame flared up and illuminated the lively joyful and tortured faces of the people who stood around the fire.

A man in a frieze overcoat, raising his hand up, shouted:

- Important! went to fight! Guys, it's important! ..

“This is the master himself,” voices were heard.

- So, so, - said Prince Andrey, referring to Alpatych, - tell everything as I told you. And, not answering a word to Berg, who fell silent beside him, he touched the horse and rode into the alley.

The troops continued to retreat from Smolensk. The enemy followed them. On August 10, the regiment commanded by Prince Andrey passed along the high road, past the avenue leading to Lysye Gory. The heat and drought lasted for over three weeks. Curly clouds walked across the sky every day, occasionally blocking the sun; but in the evening it cleared again, and the sun was setting in a brownish-red haze. Only the strong dew at night refreshed the earth. The bread remaining at the root burned and poured out. The swamps are dry. The cattle roared with hunger, finding no food on the meadows burned by the sun. Only at night and in the forests there was still dew, it was cool. But along the road, along the high road along which the troops marched, even at night, even through the forests, there was no such coolness. The dew was not noticeable on the sandy dust of the road, which had been pounded by more than a quarter of an arshin. As soon as dawn broke, movement began. Carts, artillery silently walked along the hub, and the infantry was ankle-deep in soft, stuffy, hot dust that had not cooled down during the night. One part of this sandy dust was kneaded by feet and wheels, the other rose and stood like a cloud over the army, sticking into the eyes, hair, ears, nostrils and, most importantly, into the lungs of people and animals moving along this road. The higher the sun rose, the higher the cloud of dust rose, and through this thin, hot dust on the sun, not covered by clouds, one could see with the naked eye. The sun appeared to be a large crimson ball. There was no wind and people were suffocating in this still atmosphere. People walked with handkerchiefs tied around their noses and mouths. Coming to the village, everything rushed to the wells. They fought for water and drank it to the mud.

Prince Andrey commanded the regiment, and the structure of the regiment, the well-being of its people, the need to receive and issue orders occupied him. The fire of Smolensk and its abandonment were an era for Prince Andrei. A new feeling of bitterness against the enemy made him forget his grief. He was all devoted to the affairs of his regiment, he was caring about his people and officers and kindness to them. In the regiment they called him our prince, they were proud of him and loved him. But he was kind and meek only with his regiments, with Timokhin, etc., with people completely new and in a foreign environment, with people who could not know and understand his past; but as soon as he ran into one of his former, from the staff, he immediately bristled again; became spiteful, mocking and contemptuous. Everything that connected his memory with the past repulsed him, and therefore he tried in the relations of this former world only not to be unjust and to fulfill his duty.

True, everything seemed to Prince Andrei in a dark, gloomy light - especially after they left Smolensk (which, in his opinion, could and should have been defended) on August 6, and after the sick father had to flee to Moscow and throw the Bald Hills so beloved, built and inhabited by them, to be plundered; but in spite of this, thanks to the regiment, Prince Andrey could think of another subject, completely independent of general questions - about his regiment. On August 10, the column, in which his regiment was, drew level with the Bald Mountains. Prince Andrey two days ago received news that his father, son and sister had left for Moscow. Although Prince Andrey had nothing to do in Bald Hills, he, with his usual desire to squander his grief, decided that he should stop by in Lysy Gory.

He ordered to saddle his horse and from the crossing rode on horseback to his father's village, in which he was born and spent his childhood. Driving past the pond, where dozens of women were always chatting, beating with rollers and rinsing their linen, Prince Andrey noticed that there was no one on the pond, and a torn raft, half-flooded with water, was floating sideways in the middle of the pond. Prince Andrew drove up to the gatehouse. There was no one at the stone gate of the entrance, and the door was unlocked. The garden paths were already overgrown, and the calves and horses were walking through the English park. Prince Andrew drove up to the greenhouse; the windows were broken, and some of the trees in tubs were knocked down, some were withered. He called out to Taras the gardener. Nobody responded. Turning around the greenhouse to the exhibition, he saw that the carved board fence was all broken and the plum fruit had been torn off with branches. An old peasant (Prince Andrey had seen him at the gate as a child) was sitting and weaving bast shoes on a green bench.

He was deaf and did not hear Prince Andrew's entrance. He was sitting on a bench, on which the old prince liked to sit, and near him there was a little mark on the twigs of a broken and dried magnolia.

Prince Andrew drove up to the house. Several lindens in the old garden had been cut down, and one horse with a skewbald colt walked in front of the house between the rose trees. The house was boarded up with shutters. One window at the bottom was open. The yard boy, seeing Prince Andrey, ran into the house.

Alpatych, having sent his family, remained alone in the Bald Mountains; he sat at home and read the Life. Having learned about the arrival of Prince Andrey, he, with glasses on his nose, buttoning himself up, left the house, hurriedly went up to the Prince and, without saying anything, burst into tears, kissing Prince Andrey on the knee.

Then he turned with his heart to his weakness and began to report to him about the state of affairs. Everything valuable and dear was taken to Bogucharovo. Bread, up to one hundred quarters, was also taken out; hay and spring crops, extraordinary, as Alpatych said, this year's harvest was taken and mowed green by the troops. The peasants are ruined, some have also gone to Bogucharovo, a small part remains.

Prince Andrey, without hearing him out, asked when his father and sister had left, meaning when they had left for Moscow. Alpatych answered, believing that they were asking about leaving for Bogucharovo, that they had left the seventh, and again spread about the shares of the farm, asking for instructions.

- Will you order the teams to release oats against receipt? We still have six hundred quarters left, - asked Alpatych.

“What should I say to him? - thought Prince Andrey, looking at the bald head of the old man shining in the sun and reading in the expression on his face the consciousness that he himself understands the untimeliness of these questions, but asks only in such a way as to drown out his own grief.

“Yes, let it go,” he said.

- If you were pleased to notice the disturbances in the garden, - said Alpatych, - it was impossible to prevent: three regiments passed and spent the night, especially the dragoons. I wrote out the rank and rank of the commander for filing a petition.

- Well, what are you going to do? Will you stay if the enemy takes it? Prince Andrey asked him.

Alpatych, turning his face to Prince Andrey, looked at him; and suddenly, with a solemn gesture, he raised his hand up.

- He is my patron, so be his will! He said.

A crowd of peasants and servants walked through the meadow, with open heads, approaching Prince Andrey.

- Well, goodbye! - said Prince Andrey, bending over to Alpatych. - Leave yourself, take away what you can, and the people were led to go to Ryazan or Moscow region. - Alpatych clung to his leg and sobbed. Prince Andrew carefully pushed him aside and, touching his horse, rode at a gallop down the alley.

At the exhibition, the old man sat just as indifferently as a fly on the face of a dear dead man and tapped on a shoe of bast shoes, and two girls with plums in their skirts, which they picked from the greenhouse trees, fled from there and stumbled upon Prince Andrey. Seeing the young master, the older girl, with an expression of fear on her face, grabbed her smaller companion by the hand and with her hid behind a birch tree, not having time to pick up the scattered green plums.

Prince Andrey hastily turned away from them in fright, afraid to let them notice that he had seen them. He felt sorry for this pretty frightened girl. He was afraid to look at her, but at the same time he wanted it irresistibly. A new, gratifying and reassuring feeling came over him when, looking at these girls, he realized the existence of other, completely alien to him and just as legitimate human interests as those that occupied him. These girls, obviously, longed for one thing - to carry away and eat up these green plums and not be caught, and Prince Andrey wished with them the success of their enterprise. He couldn't help but look at them again. Believing themselves already safe, they jumped out of the ambush and, for something food in thin voices, holding their skirts, merrily and quickly ran across the grass of the meadow with their tanned bare feet.

Prince Andrey freshened himself up a little, having driven out of the dust area of the main road along which the troops were moving. But not far beyond the Bald Mountains, he drove back onto the road and caught up with his regiment at a halt, at the dam of a small pond. It was two o'clock after noon. The sun, a red ball in the dust, was unbearably hot and burned my back through the black coat. The dust, still the same, stood motionless over the muttering of the halting troops. There was no wind, In the passage along the dam, Prince Andrew smelled of mud and the freshness of the pond. He wanted to go into the water - no matter how dirty it was. He looked back at the pond, from which shouts and laughter were heard. A small muddy pond with greenery, apparently, had risen by two quarters, flooding the dam, because it was full of human, soldier's, naked white bodies floundering in it, with brick-red hands, faces and necks. All this naked, white human meat with laughter and boom floundered in this dirty puddle, like crucians stuffed into a watering can. This floundering echoed with merriment, and that is why it was especially sad.

One young blond soldier — Prince Andrey knew him — of the third company, with a strap under his calf, crossing himself, stepped back to take a good run and plunge into the water; another, black, always shaggy non-commissioned officer, waist-deep in water, twitching his muscular waist, snorted joyfully, pouring his black hands over his head. There was a spanking on each other, and a squeal, and a hoot.

On the banks, on the dam, in the pond, there was white, healthy, muscular meat everywhere. Officer Timokhin, with a red nose, wiped himself off on the dam and was ashamed when he saw the prince, but decided to turn to him:

- That is good, your Excellency, you would have deigned! - he said.

“Dirty,” said Prince Andrew, wincing.

- We'll clean it up for you now. - And Timokhin, not yet dressed, ran to clean.

- The prince wants.

- Which? Our prince? - spoke the voices, and everyone was in such a hurry that Prince Andrey could not calm them down. He came up with a better shower in the barn.

“Meat, body, chair a canon [cannon fodder]! - he thought, looking at his naked body, and shuddering not so much from the cold as from his own incomprehensible disgust and horror at the sight of this huge number of bodies rinsing in a dirty pond.

On August 7, Prince Bagration in his parking lot Mikhailovka on the Smolensk road wrote the following:

“Dear sir, Count Alexey Andreevich.

(He wrote to Arakcheev, but he knew that his letter would be read by the sovereign, and therefore, as far as he was able to do so, he considered his every word.)

I think that the minister has already reported on the abandonment of Smolensk to the enemy. It hurts, it is sad, and the whole army is in despair that the most important place was in vain abandoned. I, for my part, asked him personally in the most convincing way, and finally wrote; but nothing agreed. I swear to you on my honor that Napoleon was in such a sack as never before, and he could have lost half of his army, but not take Smolensk. Our troops have fought and are fighting as never before. I held on with 15 thousand for more than 35 hours and beat them; but he didn’t want to stay even 14 o'clock. It is a shame, and the stain of our army; and he himself, it seems to me, should not even live in the world. If he reports that the loss is great, it is not true; maybe about 4 thousand, no more, but not even that. At least ten, how to be, war! But the enemy lost the abyss ...

Alberti's biography is also known as the story of the first architect who challenged the use of classical orders during the Renaissance. His ecclesiastical works include the exteriors of the churches of San Francesco in Rimini (beginning in 1451), San André in Mantua (completed in 1470), as well as partially the façade of the Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence (1458-1470).

On the facade of the Ruchelai Palace in Florence (1452-1470), Alberti arranged the classical elements of architecture in tiers, slightly overlapping the rows one on top of the other. So the architect gave the building a resemblance to the Roman Colosseum.

During his biography, Leon Battista Alberti wrote several treatises, one way or another related to art. His work "De re aedificatoria", written in 1450, became the first printed book on architecture (published in 1485). Despite the significant dependence on the work of Vitruvius, Alberti's book became the first modern book on this topic, includes the most important material.

Léon Battista's treatise on painting (1436) was also the first book in the field, taking theory as seriously as technique. His treatise on sculpture (1464) is another pioneering work, highly significant in the debate over the depiction of human proportions.

Biography score

Alberti Leon Battista (1404-1472)

Early Renaissance Italian scientist, architect, writer and musician. He received a humanistic education in Padua, studied law in Bologna, and later lived in Florence and Rome. In the theoretical treatises "On the Statue" (1435), "On Painting" (1435-1436), "On Architecture" (published in 1485), the experience of contemporary Italian art Alberti enriched the achievements of humanistic science and philosophy. Leon Battista Alberti defended the "folk" (Italian) language as a literary language, in the ethical treatise "On the Family" (1737-1441) he developed the ideal of a harmoniously developed personality. In architectural work, Alberti gravitated towards bold, experimental solutions.

Leon Battista Alberti designed a new type of palazzo with a façade treated with rustic stone to its full height and dissected by three tiers of pilasters that look like the structural basis of the building (Palazzo Rucellai in Florence, 1446–1451, built by B. Rossellino according to Alberti's plans). While rebuilding the façade of the Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence (1456–1470), Alberti first used volutes to connect its middle part with lowered lateral ones. Striving for grandeur and at the same time for the simplicity of the architectural image, Alberti used the motives of the ancient Roman triumphal arches and arcades in the design of the facades of the churches of San Francesco in Rimini (1447-1468) and Sant Andrea in Mantua (1472-1494), which became important a step in the mastering of the ancient heritage by the masters of the Renaissance.

Alberti was not only the greatest architect of the mid-15th century, but also the first theoretical encyclopedist in Italian art, who wrote a number of outstanding scientific treatises on art (treatises on painting, sculpture and architecture, including his famous work "Ten Books on Architecture") ...

Alberti had a significant influence on contemporary architectural practice not only with his buildings, unusual and deeply peculiar in compositional design and sharpness of the artistic image, but also with his scientific works in the field of architecture, which, along with the works of ancient theorists, were based on the building experience of the masters of the Renaissance ...

Unlike other masters of the Renaissance, Alberti, as a theoretical scientist, was not able to pay enough attention to direct activities on the construction of the structures he conceived, entrusting their implementation to his assistants. The not always successful choice of construction assistants led to the fact that there were a number of architectural errors in Alberti's buildings, and the quality of construction work, architectural details and ornamentation was sometimes low. However, the great merit of Alberti the architect lies in the fact that his constant innovative searches paved the way for the emergence and flowering of the monumental style of the High Renaissance.

The name Alberti is rightfully called one of the first among the great creators of the culture of the Italian Renaissance. His theoretical works, his artistic practice, his ideas and, finally, his very personality as a humanist played an extremely important role in the formation and development of the art of the early Renaissance.

“A man should have appeared,” wrote Leonardo Olszki, “who, possessing theory and having a vocation for art and practice, would put the aspirations of his time on a solid foundation and give them a certain direction in which they were to develop in the future. but at the same time the harmonious mind was Leon Battista Alberti. "

Leon Battista Alberti was born on February 18, 1404 in Genoa. His father, Leonardo Alberti, whose illegitimate son was Leon, belonged to one of the influential merchant families of Florence, expelled from his hometown by political opponents.

Leon Battista received his initial education in Padua, at the school of the famous humanist educator Gasparino da Barzizza, and after the death of his father in 1421 he left for Bologna, where he studied canon law at the university and attended lectures by Francesco Filelfo on Greek language and literature. Upon graduation from the university in 1428, he was awarded the title of Doctor of Canon Law.

Although in Bologna, Alberti fell into the brilliant circle of writers who gathered in the house of Cardinal Albergati, these university years were difficult and unlucky for him: the death of his father sharply undermined his material well-being, litigation with relatives because of the inheritance they illegally rejected, deprived him of peace, overworking he ruined his health.

With his student years, the beginning of Alberti's hobbies for mathematics and philosophy is associated. In the early works of Alberti (Philodoxus, On the Advantages and Disadvantages of Science, Table Conversations) of the Bolognese period, there is anxiety and anxiety, the consciousness of the inevitability of a blind fate. Contact with Florentine culture, after being allowed to return to their homeland, contributed to the elimination of these sentiments.

During a trip to France, the Netherlands and Germany with Cardinal Albergati's retinue in 1431, Alberti received a lot of architectural impressions. The subsequent years of his stay in Rome (1432-1434) were the beginning of his many years of studying the monuments of ancient architecture. At the same time, Alberti began to study cartography and the theory of painting, while working on the essay "On the Family", devoted to the problems of morality.

In 1432, under the patronage of influential patrons from the highest clergy, Alberti was promoted to the papal chancellery, where he served for over thirty years.

Best of the day

Alberti's hard work was truly immeasurable. He believed that a person, like a sea ship, must travel vast spaces and "strive to earn praise and the fruits of glory through labor." As a writer, he was equally interested in the foundations of society, and the life of the family, and the problems of the human personality, and questions of ethics. He was engaged not only in literature, but also in science, painting, sculpture and music.

His "Mathematical Fun", as well as the treatises "On Painting", "On the Statue", testify to the thorough knowledge of their author in the field of mathematics, optics, mechanics. He monitors the humidity of the air, which is why a hygrometer is born.

He is thinking about creating a geodetic instrument to measure the height of buildings and the depth of rivers and to facilitate the leveling of cities. Alberti designs lifting mechanisms for retrieving sunken Roman ships from the bottom of the lake. Such minor things as the cultivation of valuable breeds of horses, the secrets of the women's toilet, the code of encrypted papers, the form of writing letters, do not escape his attention.

The diversity of his interests so amazed his contemporaries that one of them wrote in the margins of the Alberti manuscript: "Tell me, what did this man not know?"

If you try to give a general description of the entire work of Alberti, then the most obvious will be the desire for innovation, organically combined with thoughtful penetration into ancient thought.

In 1434-1445, in the retinue of Pope Eugene IV, Alberti visited Florence, Ferrara, Bologna. During a long stay in Florence, he struck up friendly relations with the founders of Renaissance art - Brunelleschi, Donatello, Ghiberti. Here he wrote his treatises on sculpture and painting, as well as his best humanistic works in Italian - "On the Family", "On Peace of Mind", which made him a universally recognized theorist and a leading figure in the new artistic movement.

Repeated trips to the cities of Northern Italy also contributed a lot to awakening his keen interest in a variety of artistic activities. Returning to Rome, Alberti renewed his studies of ancient architecture with renewed vigor and in 1444 began compiling the treatise "Ten Books on Architecture".

By 1450, the treatise was roughly finished, and two years later, in a more corrected edition - the one that is known today - was given to Pope Nicholas V. did not return to him.

Alberti's first architectural experiences are usually associated with his two stays in Ferrara, in 1438 and 1443. Being on friendly terms with Lionello d "Este, who became Marquis of Ferrara in 1441, Alberti advised the construction of an equestrian monument to his father, Niccolò III.

After Brunelleschi's death in 1446 in Florence, not a single architect of his equal importance remained among his followers. Thus, at the turn of the century, Alberti found himself in the role of the leading architect of the era. Only now he received real opportunities to put his architectural theories into practice.

All of Alberti's buildings in Florence are marked by one remarkable feature. The principles of the classical order, extracted by the master from the Roman antique architecture, were applied by him with great tact to the traditions of Tuscan architecture. New and old, forming a living unity, gives these buildings a unique "Florentine" style, very different from the one in which his buildings were made in Northern Italy.

Alberti's first work in his hometown was the design of a palace for Giovanni Rucellai, the construction of which was carried out between 1446 and 1451 by Bernard Rossellino. Palazzo Rucellai is very different from all the buildings in the city. Alberti "imposes" a grid of classical orders on the traditional scheme of the three-story facade.

Instead of a massive wall formed by rusticated masonry of stone blocks, the powerful relief of which is gradually smoothed out as we move up, we have a smooth plane rhythmically dissected by pilasters and ribbons of entablatures, clearly outlined in its proportions and completed by a significantly extended cornice.

Small square windows on the first floor, raised high from the ground, columns separating the windows of the two upper floors, and the fractional running of cornice modulons greatly enrich the overall rhythm of the facade. In the architecture of the city house, traces of the former isolation and the "serf" character that was inherent in all other palaces in Florence at that time disappear. It is no coincidence that Filarete, referring to the building of Alberti in his treatise, noted that in it "the entire facade ... is made in the antique manner."

Alberti's second most important building in Florence was also associated with the Rucellai order. One of the richest people in the city, he, according to Vasari, "wanted to make at his own expense and entirely of marble the facade of the Church of Santa Maria Novella", entrusting the project to Alberti. The work on the facade of the church, which began in the 14th century, was not completed. Alberti had to continue what the Gothic masters had begun.

This made it difficult for him, because, without destroying what had been done, he was forced to include in his project elements of the old decoration - narrow side doors with lancet tympans, lancet arches of external niches, a breakdown of the lower part of the facade with thin lisens with arcatures in the proto-Renaissance style, a large round window in top part. Its façade, which was built between 1456 and 1470 by the master Giovanni da Bertino, was a kind of classical paraphrase of samples of the proto-Renaissance style.

Alberti performed other work at the request of his patron. In the church of San Pancrazio, adjacent to the back of the Palazzo Rucellai, in 1467 the family chapel was built according to the master's design. Decorated with pilasters and geometric inlay with rosettes of various patterns, it is stylistically close to the previous building.

Despite the fact that the buildings, created in Florence according to Alberti's projects, in their style closely adjoined the traditions of Florentine architecture, they had only an indirect influence on its development in the second half of the 15th century. Alberti's work in Northern Italy developed in a different way. And although his buildings were created there simultaneously with the Florentine ones, they characterize a more significant, more mature and more classical stage in his work. In them, Alberti more freely and boldly tried to carry out his program of "revival" of Roman ancient architecture.

The first such attempt was associated with the rebuilding of the Church of San Francesco in Rimini. The tyrant of Rimini, the famous Sigismondo Malatesta, came up with the idea to make this ancient church a family temple-mausoleum. By the end of the 1440s, the memorial chapels of Sigismondo and his wife Isotta were completed inside the church. Apparently, Alberti was involved in the work at the same time. Around 1450, a wooden model was made according to his project, and later he very closely followed the progress of construction from Rome, which was led by the local master - miniaturist and medalist Matgeo de "Pasti.

Judging by the medal of Matteo de Pasti, dated to the anniversary year 1450, which depicted a new temple, Alberti's project involved a radical restructuring of the church. First of all, it was planned to make new facades on three sides, and then erect a new vault and choir, covered with a large dome.

Alberti got at his disposal a very ordinary provincial church - squat, with pointed windows and wide pointed arches of chapels, with a simple rafter roof over the main nave. He planned to transform it into a magnificent memorial temple, able to rival the ancient sanctuaries.

The monumental façade in the form of a two-tiered triumphal arch had very little in common with the familiar appearance of Italian churches. The spacious domed rotunda, which opened to the visitor in the depths of the vaulted hall, evoked memories of the buildings of ancient Rome.

Unfortunately, Alberti's plan was only partially realized. Construction was delayed. The main facade of the temple remained unfinished, and what was done in it did not exactly correspond to the original project

Simultaneously with the construction of the "Temple of Malatesta" in Rimini, according to Alberti's designs, a church was being erected in Mantua. The Marquis of Mantua, Lodovico Gonzaga, patronized humanists and artists. When in 1459 Alberti appeared in Mantua in the retinue of Pope Pius II, he received a very warm welcome from Gonzaga and maintained friendly relations with him until the end of his life.

At the same time, Gonzaga commissioned Alberti to draw up a project for the church of San Sebastiano. Remaining in Mantua after the departure of the pope, Alberti completed a model of a new church in 1460, the construction of which was entrusted to the Florentine architect Luca Fancelli, who was at the Mantuan court. At least twice more, in 1463 and 1470, Alberti came to Mantua to follow the progress of the work, corresponded on this matter with the Marquis and Fancelli:

The new Alberti Church was a centric building. Cruciform in plan, it had to be covered with a large dome. Three short protruding stands ended in semicircular apses. And from the fourth side, a wide two-story bunk-tex-vestibule adjoined the church, forming a facade facing the street.

Where the narthex was connected by its rear wall with a narrower entrance tribune, on either side of it, filling the free space, two bell towers were supposed to rise. The building is raised high above ground level. It was erected on the basement floor, which was a vast crypt under the entire temple with a separate entrance to it.

The façade of San Sebastiano was conceived by Alberti as an exact resemblance to the main portico of the ancient Roman temple-periptera. A high staircase led to five entrances to the vestibule, the steps of which extended the entire width of the facade, completely hiding the passages to the crypt.

His idea of decorating a wall with pilasters of a large order reconciles the doctrine of classical architecture, for which he so advocated in his treatise, with the practical needs of the architecture of his time.

The architecture of the Italian Renaissance has not yet known such a constructive and decorative solution for the internal space of the church. In this respect, Bramante became the true heir and successor of Alberti. Moreover, the construction of Alberti was a model for all subsequent church architecture of the late Renaissance and Baroque.

The Venetian churches of Palladio, Il Gesu Vignola and many other churches of the Roman Baroque were built on its type. But Alberti's innovation was especially important for the architecture of the High Renaissance and Baroque - the use of a large order in the decoration of the facade and interior.

In 1464, Alberti left the curia, but continued to live in Rome. His last works include a treatise in 1465 on the principles of composing codes, and an essay in 1470 on moral topics. Leon Battista Alberti died on April 25, 1472 in Rome.

Alberti's last project took place in Mantua, after his death, in the years 1478-1480. This is the Capella del Incoronata of the Mantua Cathedral. The architectural clarity of the spatial structure, the excellent proportions of the arches easily supporting the dome and vaults, the rectangular portals of the doors - all betray the classicizing style of the late Alberti.

Alberti stood at the center of Italy's cultural life. Among his friends were the greatest humanists and artists (Brunelleschi, Donatello and Luca della Robbia), scientists (Toscanelli), the powers that be (Pope Nicholas V, Piero and Lorenzo Medici, Giovanni Francesco and Lodovico Gonzaga, Sigismondo Malatesta, Lionello d "Este, Federigo de Mon-tefeltro).

And at the same time, he did not shy away from the barber Burkiello, with whom he exchanged sonnets, willingly stayed up late into the evening in the workshops of blacksmiths, architects, shipbuilders, shoemakers, in order to find out from them the secrets of their art

Alberti far surpassed his contemporaries in talent, curiosity, versatility, and a special liveliness of mind. He happily combined a subtle aesthetic feeling and the ability to think reasonably and logically, while relying on the experience gained from communication with people, nature, art, science, classical literature. Painful from birth, he managed to make himself healthy and strong. Due to failures in life, prone to pessimism and loneliness, he gradually came to accept life in all its manifestations.