Which scientist was able to decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphs? How the mystery of Egyptian hieroglyphs was solved.

Read also

Penetration into the history of Ancient Egypt for a long time was hindered by the barrier of Egyptian writing. Scientists have tried to read Egyptian hieroglyphs for a long time. However, all attempts to overcome the "Egyptian letter" remained in vain. In the end, by the beginning of the 19th century, all work on deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs had reached a dead end.

But there was a man who held a different opinion: Jean François Champollion (1790-1832). Getting acquainted with his biography, it is difficult to get rid of the feeling that this brilliant French linguist came to our world only to give science the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs. Judge for yourself: at the age of five, Champollion learned to read and write without assistance, by the age of nine he independently mastered Latin and Greek, at the age of eleven he read the Bible in Hebrew, at the age of thirteen he began to study Arabic, Syriac, Chaldean and Coptic languages, at fifteen years he began to study the Persian language and Sanskrit, and "for fun" (as he wrote in a letter to his brother) - Chinese. For all that, he did poorly at school!

Champollion began to take an interest in Egypt at the age of seven. One day he got hold of a newspaper, from which he learned that in March 1799 a soldier from Napoleon's expeditionary corps had found near Rosetta, a small Egyptian village in the Nile Delta, “a flat basalt stone the size of a writing-table, on which two Egyptian and one Greek inscription. " The stone was transported to Cairo, where one of Napoleon's generals, a passionate Hellenistic amateur, read a Greek inscription on the stone: in it, the Egyptian priests thanked Pharaoh Ptolemy I Epiphanes for the benefits rendered to them in the ninth year of his reign (196 BC) temples. To glorify the king, the priests decided to erect his statues in all the sanctuaries of the country. In conclusion, they reported that, in memory of this event, an inscription "in sacred, native and Hellenic letters" was carved on the memorial stone. The anonymous newspaper writer concluded his publication with the assumption that now "by comparison with Greek words it is possible to decipher the Egyptian text."

The Rosetta Stone became the key to unraveling Egyptian hieroglyphic and demotic writing. However, before the "era of Champollion" only very few scientists managed to make progress in deciphering the texts carved on it. Only the genius of Champollion could solve this unsolvable, as it seemed then, problem.

The scientist's path to the desired goal was not straightforward. Despite the fundamental scientific training and tremendous intuition, Champollion had to bump into dead ends every now and then, go the wrong way, turn back and again make his way to the truth. Of course, a big role was played by the fact that Champollion spoke a dozen ancient languages, and thanks to his knowledge of Coptic, he could more than anyone else come closer to understanding the very spirit of the language of the ancient Egyptians.

In 1820 Champollion correctly determines the sequence of the types of Egyptian writing (hieroglyphics - hieratic - demotics). By this time, it was already clearly established that in the latest form of writing - demotic - there are signs-letters. On this basis, Champollion comes to the conviction that sound signs should also be sought among the earliest type of writing - hieroglyphics. He examines the royal name "Ptolemy" on the Rosetta stone and singles out 7 hieroglyphs-letters in it. Studying a copy of the hieroglyphic inscription on an obelisk originating from the Temple of Isis on the island of Philae, he reads the name of Queen Cleopatra. As a result, Champollion determined the sound meaning of five more hieroglyphs, and after reading the names of other Greco-Macedonian and Roman rulers of Egypt, he increased the hieroglyphic alphabet to nineteen characters.

It remained to answer an important question: maybe only foreign names were transmitted in hieroglyphs-letters, in particular, the names of the rulers of Egypt from the Ptolemaic dynasty, and the real Egyptian words were written in a non-sound way? The answer to this question was found on September 14, 1822: on that day Champollion was able to read the name "Ramses" on a copy of a hieroglyphic inscription from a temple in Abu Simbel. Then the name of another pharaoh was read - "Thutmose". Thus, Champollion proved that already in ancient times the Egyptians, along with symbolic hieroglyphic signs, used alphabetic signs.

On September 27, 1822, Champollion spoke to members of the Academy of Inscriptions and Literature with a report on the progress of deciphering Egyptian writing. He spoke about the method of his research and concluded that the Egyptians had a semi-alphabetic writing system, since they, like some other peoples of the East, did not use vowels in writing. And in 1824 Champollion published his main work "An Outline of the Hieroglyphic System of the Ancient Egyptians." She became the cornerstone of modern Egyptology.

Champollion discovered the Egyptian writing system, establishing that it was based on the sound principle. He deciphered most of the hieroglyphs, established the relationship between hieroglyphic and hieratic writing and both of them with demotic, read and translated the first Egyptian texts, compiled a dictionary and grammar of the ancient Egyptian language. In fact, he resurrected this dead language!

In July 1828, a truly historic event took place: a person who knew the language of the ancient Egyptians came to Egypt for the first time. After many years of armchair labors, Champollion now had to make sure in practice that his conclusions were correct.

Having landed in Alexandria, Champollion first of all "kissed the Egyptian land, setting foot on it for the first time after many years of impatient waiting." He then went to Rosetta and found the place where the Rosetta Stone was found to thank the Egyptian priests for that 196 BC inscription. e., which played an extremely important role in the deciphering of hieroglyphs. From here, the scientist traveled along the Nile to Cairo, where he finally saw the famous pyramids. “The contrast between the size of the building and the simplicity of the form, between the colossal nature of the material and the weakness of the person who built these gigantic creations, defies description,” wrote Champollion. “When you think about their age, you can say after the poet:“ Their ineradicable mass has tired the time ”. In the Sakkar necropolis, the scientist made a very significant discovery: his employee dug up a stone with a hieroglyphic inscription near one of the dilapidated pyramids, and Champollion read the royal name on it and identified it with the name of the last pharaoh of the 1st dynasty of Unis (Onnos), which was known from the works of the ancient historian Manetho. Half a century passed before the correctness of Champollion's conclusion was confirmed.

However, Champollion did not study the pyramids in detail: he was looking for inscriptions. After visiting the ruins of Memphis, he went down the Nile. In Tell-el-Amarna, he discovered and investigated the remains of a temple (later on this place the city of Akhetaton was discovered), and in Dendera he saw the first surviving Egyptian temple.

This one of the largest Egyptian temples began to be built by the pharaohs of the XII dynasty, the most powerful rulers of the New Kingdom: Thutmose III and Ramses II the Great. “I will not even try to describe the deep impression that this large temple made on us, and especially its portico,” wrote Champollion. - Of course, we could give its dimensions, but it is simply impossible to describe it in such a way that the reader has a correct idea of it ... there are inscriptions on the walls. "

Until now, there was a belief that the temple at Dendera was dedicated to the goddess Isis, but Champollion was convinced that this was the temple of Hathor, the goddess of love. Moreover, it is not at all ancient. It acquired its present appearance only under the Ptolemies, and was finally completed by the Romans.

From Dendera Champollion went to Luxor, where he investigated the temple of Amun at Karnak and determined the individual stages of its long-term construction. A giant obelisk covered with hieroglyphs caught his attention. Who ordered it to be erected? The hieroglyphs enclosed in a cartouche frame answered this question: Hatshepsut, the legendary queen who ruled Egypt for more than twenty years. “These obelisks are made of hard granite from the southern quarries,” Champollion read the text engraved on the surface of the stone. - Their tops are made of pure gold, the finest that can be found in all foreign countries. They can be seen by the river from afar; the light of their rays fills both sides, and when the sun stands between them, it truly seems that it rises to the edge (?) of the sky ... To gild them, I gave out gold, which was measured by sheffels, as if they were sacks of grain ... Because I knew that Karnak is the heavenly border of the world. "

Champollion was deeply shocked. He wrote to his friends in distant France: “I finally got to the palace, or rather to the city of palaces - Karnak. There I saw all the luxury in which the pharaohs lived, everything that people could invent and create on a gigantic scale ... Not a single people of the world, neither ancient nor modern, understood the art of architecture and did not implement it on such a grand scale as it was done ancient Egyptians. Sometimes it seems that the ancient Egyptians thought in terms of the scale of people a hundred feet tall! "

Champollion crossed to the western bank of the Nile, visited the tombs in the Valley of the Kings and the ruins of the temple of Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahri. “Everything I saw delighted me,” wrote Champollion. "Although all these buildings on the left bank pale in comparison with the giant stone wonders that surrounded me on the right."

Then the scientist continued his journey south, to the rapids of the Nile, visited Elephantine and Aswan, and visited the temple of Isis on the island of Philae. And everywhere he copied inscriptions, translated and interpreted them, made sketches, compared architectural styles and established differences between them, determined to which era certain finds belong. He made discovery after discovery. “I can declare with full responsibility,” wrote Champollion, “that our knowledge about Ancient Egypt, especially about its religion and art, will be significantly enriched as soon as the results of my expedition are published”.

Champollion spent a year and a half in Egypt, and during this time he passed the country from edge to edge. The scientist did not spare himself, several times he received a sunstroke, twice he was taken out of the underground tombs unconscious. With such loads, even the healing Egyptian climate could not cure him of tuberculosis. And when Champollion returned home in December 1829, his days were numbered. He still managed to process the results of the expedition. However, the scientist did not live to see the publication of his last works - "Egyptian Grammar" (1836) and "Egyptian Dictionary in Hieroglyphic Writing" (1841). He died on March 4, 1832 from apoplectic stroke.

Champollion Jean Francois- an outstanding French scientist, founder of Egyptology. Deciphered ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. Member of the Academy of Inscriptions (since 1830).

Ancient Egyptian civilization, which existed for several millennia, gradually fell into decay, and after Ramses II (XXII century BC) the slow decline of Egypt began. In the middle of the first millennium BC, Egypt fought with Assyria, Libya, Persia, and others.

In 332 BC. the army of Alexander the Great entered Egypt and Ancient Egypt became part of his state. Then gradual Hellenization during the Ptolemaic era. Egypt became the main supplier of bread, and its culture, art, writing gradually faded.

In 332 BC. the army of Alexander the Great entered Egypt and Ancient Egypt became part of his state. Then gradual Hellenization during the Ptolemaic era. Egypt became the main supplier of bread, and its culture, art, writing gradually faded.

During the early Middle Ages, various conquerors again invaded Egypt, as a result, all the achievements of the culture of draenei Egypt were forgotten, no one used hieroglyphs, the tombs were mostly plundered in those distant times ... Egyptian writing was often perceived as part of the decorative ornament of ancient and incomprehensible culture.

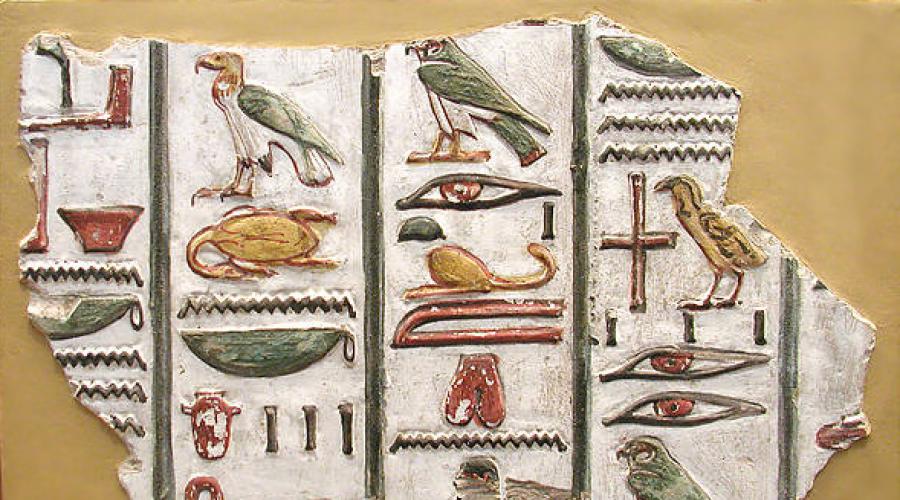

This is how the writing of Ancient Egypt looks like, the language of which also became "dead", and for many centuries no one was interested in these writings. But in the XIX century interest in Ancient Egypt arose, archaeologists made amazing discoveries, linguists and philologists tried to decipher and read the inscriptions, but alas.

Nobody succeeded. Nobody! In addition to the great genius linguist Jean Francois Champollion, whose biography we will now get to know.

JEAN-FRANCOIS CHAMPOLION. Biography

Jean-François Champollion was born on December 23, 1790 in the city of Figeac in the province of Dauphine and was the youngest of seven children, two of whom died in infancy, before his birth. Interest in ancient history in the wake of the increased attention to Ancient Egypt after the Egyptian campaign of Napoleon Bonaparte 1798-1801 was developed by his brother, archaeologist Jacques-Joseph Champollion-Figeac.

Jean-François Champollion was born on December 23, 1790 in the city of Figeac in the province of Dauphine and was the youngest of seven children, two of whom died in infancy, before his birth. Interest in ancient history in the wake of the increased attention to Ancient Egypt after the Egyptian campaign of Napoleon Bonaparte 1798-1801 was developed by his brother, archaeologist Jacques-Joseph Champollion-Figeac.

My father had a book trade, the family was well-to-do and this made it possible to give children an excellent education. From an early age, Jean-François showed a keen interest in antiquity, was extremely fond of ancient languages and literature, and showed genius aptitude for philology and the study of languages. Studying at the primary school of Figeac, and then at the "Central School" of Grenoble, where he lived with his older brother from the age of ten, he independently studies classical languages and Hebrew, is fond of reading Homer and Virgil.

At the age of eleven, Champollion first became acquainted with Egyptian antiquities. Champollion's elder brother Jacques-Joseph introduces him to the Mathematician Joseph Fourier, a member of the Napoleonic expedition to Egypt. This expedition brought hitherto unseen papyri and other Egyptian antiquities. This acquaintance irrevocably decides his future fate and scientific interests.

After three years at the Lyceum (1804 - 1807), Francois Champollion moved to Paris, where he studied Arabic and Coptic at the School of Living Oriental Languages. In addition, he becomes familiar with the Persian language, Sanskrit and the Chinese writing system. Champollion considers mastering these languages a preparatory work, providing penetration into the secret of reading the hieroglyphic writing of the ancient Egyptians.

They say that when the famous phrenologist Gall, popularizing his theory, traveled around the cities and villages, he was once introduced to a young student in a society in Paris. Barely having time to glance at the skull of Francois Champollion, the famous skull-scientist exclaimed: "Oh, what a brilliant linguist!" In this case, the phrenologist Gall was 100% right, although modern science does not recognize phrenology - the science of the relationship between the structure of the skull and the human psyche.

At the age of 16, François Champollion made a map of the Nile Valley of the era of the Ancient Kingdoms, and then presented his book "Egypt under the Pharaohs" to the court of scientists. The scientific research of the young Egyptologist was highly appreciated at a meeting of the Grenoble Academy and gray-haired scientists awarded the 19-year-old boy the title of professor.

Twenty-year-old François Champollion was fluent in French, Latin, Ancient Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Coptic, Zend, Pahlavi, Syriac, Aramaic, Farsi, Amharic, Sanskrit, and Chinese. A young scientist needs this in order to solve the main scientific problem of his life - to decipher the Egyptian hierglyphs.

In 1808 Champollion got acquainted with the text of the famous Rosetta Stone from a cast and, despite the need, led an intense research life. He wrote works on Egyptian religion and on the grammar of the Theban dialect of the Coptic language. At the age of nineteen, in 1809, Champollion returned to Grenoble as a professor at the Department of Oriental Languages and continued to work on deciphering Egyptian inscriptions.

In 1808 Champollion got acquainted with the text of the famous Rosetta Stone from a cast and, despite the need, led an intense research life. He wrote works on Egyptian religion and on the grammar of the Theban dialect of the Coptic language. At the age of nineteen, in 1809, Champollion returned to Grenoble as a professor at the Department of Oriental Languages and continued to work on deciphering Egyptian inscriptions.

During the Hundred Days of Napoleon, the emperor on his way to the capital visited Grenoble and met with a young scientist. He was keenly interested in his work, inquired about languages and Coptic grammar, about the dictionary, and promised to publish his books. But the Bourbons are returning to the throne. Champollion lost his professorship in Grenoble in 1815 as a Bonapartist and an opponent of the monarchy. Deprived of his livelihood in Grenoble, he moved to Paris.

Then Champollion proceeded to the final deciphering of the hieroglyphs, and after many years of work on the inscription of the Rosetta Stone. In 1822, his work "Letter to Monsieur Dassier concerning the alphabet of phonetic hieroglyphs" ("Lettre à Mr. Dacier relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques") was published Champollion summed up his first studies in the field of deciphering hieroglyphs, and the appearance of his next work "A brief outline of the hieroglyphic system of the ancient Egyptians or a study of the elements of this letter" (1824) was the beginning of the existence of Egyptology.

In these works, the foundations of deciphering hieroglyphs are set forth, which revealed the secret of Egyptian writing. The name of Jean-Francois Champollion became known to everyone who turned their eyes to the country of pyramids and temples, trying to unravel its secrets. In 1824-1826. Champollion studied Egyptian monuments in museums in Italy.

Continuing to further develop his achievements in the field of writing and language, Champollion drew attention to the issues of Egyptian geography, chronology, art. In 1828-1829. Champollion visited Egypt, where he led a large complex expedition, the results of which were published only after his death (in 1835-1845) entitled "Monuments of Egypt and Nubia." Upon his return to France, he revised a number of his works, completed the grammar of the ancient Egyptian language and organized the Paris branch of Egyptian antiquities in the Louvre Museum and was appointed curator of the Egyptian Museum at the Louvre.

Champollion clearly proved the connection between different types of Egyptian writing: hieroglyphic, hieratic (cursive) and demotic (cursive). Then he correctly grasped the mixed character of Egyptian writing. His predecessors considered certain types of Egyptian writing to be either ideographic or phonetic. Champollion, however, proved that in written records of various eras, writing signs had both phonetic and ideographic significance.

In 1828-1829, together with the Italian linguist Ippolito Rosellini, he made his first expedition to Egypt and Nubia. During the expedition, he studied a huge number of ancient Egyptian monuments and inscriptions, fruitfully worked on the collection and research of epigraphic and archaeological material.

During this expedition in Egypt, Champollion finally undermined his poor health and died in Paris as a result of a stroke at the age of 41 (1832), without having time to systematize the results of his expedition.

Further development of science showed the complete correctness of Champollion's conclusions and his complete independence from the work of other scientists who disputed the honor of opening the reading of Egyptian writing. Champollion especially challenged this honor of discovery by his unfortunate predecessor Jung. But even then the greatest orientalist Sylvester de Sacy and linguist Alexander Humboldt recognized the honor of opening the reading of the Egyptian letter belongs to Jean-François Champollion.

Ancient civilizations possessed unique and mysterious knowledge, many of which were lost over time or taken to the grave by the owners themselves. Egyptian hieroglyphs were one such mystery. People were eager to unravel their secret, desecrating tomb after tomb for this. But only one person managed to do this. So, which scientist was able to decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphs?

What it is?

The ancient Egyptians believed that hieroglyphs are the words of God. They speak, point out and remain silent. That is, they had three purposes: writing and reading, expression of thoughts, a way of transmitting secrets between generations.

During the period, more than seven hundred characters were included in the Egyptian alphabet. Hieroglyphs had many meanings. One sign could carry a variety of meanings.

In addition, there were special hieroglyphs that the priests used. They included volumetric mental forms.

In those days, hieroglyphs were much more important than modern letters. They were credited with magical powers.

Rosetta stone

In the summer of 1799, Napoleon's expedition was in Egypt. During the digging of trenches in the vicinity of the city of Rosetta, a large stone was dug out of the ground, covered with mysterious letters.

Its upper part was broken off. It contains hieroglyphs in fourteen lines. Moreover, they were knocked out from left to right, which is not typical for oriental languages.

The middle part of the stone surface contained 32 lines of hieroglyphs, engraved from right to left. They have been most fully preserved.

On the lower part of the stone, letters were engraved in Greek. They were located in 54 lines, but not completely preserved, because a corner was broken off from the stone.

Napoleon's officers realized that they had made an important find. The Greek letters were immediately translated. They told about the decision of the priests to erect a statue of the ruler of Egypt, the Greek Ptolemy Epiphanes, near the statue of the deity. And to appoint the days of his birth and accession to the throne as temple holidays. Then there was a text stating that this inscription was repeated by the sacred hieroglyphs of Egypt and demonic signs. It is known that Ptolemy Epiphanes ruled in 196 BC. NS. Nobody could translate other letters.

The stone was placed in the Egyptian Institute, which was founded by Napoleon in Cairo. But the English fleet defeated the French army and fortified itself in Egypt. The mysterious stone was donated to the British National Museum.

The mystery of Egyptian hieroglyphs has interested scientists all over the world. But it was not so easy to find out its solution.

Chapmollion from Grenoble

Jacques-Francois Champollion was born in December 1790. He grew up a very smart boy, he loved to spend time with a book in his hand. At the age of five, he independently studied the alphabet and learned to read. At the age of 9, he was fluent in Latin and Greek.

The boy had an older brother, Joseph, who was passionate about Egyptology. Once the brothers were visiting the prefect, where they saw a collection of Egyptian papyri, covered with mysterious signs. At that moment Champollion decided that the secret of the Egyptian hieroglyphs would be revealed to him.

At the age of 13, he began to study Hebrew, Arabic, Persian, Coptic and Sanskrit. While studying at the Lyceum, François wrote a study about Egypt during the time of the pharaohs, which made a splash.

Then the young man had a period of long study and hard work. He saw a copy of the Rosetta Stone, which was of poor quality. To make out each symbol, you had to look closely at it.

In 1809 Champollion became professor of history at the University of Grenoble. But during the accession of the Bourbons, he was expelled from him. In difficult years for the scientist, he worked on solving the Rosetta Stone.

He realized that there are three times more hieroglyphs than words in Greek letters. Then Champollion was struck by the idea that they are a semblance of letters. In the course of further work, he realized that the Egyptian alphabet of hieroglyphs contained three types.

The first type is symbols that were carved in stone. They were portrayed large and clear, with meticulous artistic portrayal.

The second type is hieratic signs, which represent the same hieroglyphs, but depicted not so clearly. This writing was used on papyrus and limestone.

The third type is the Coptic alphabet, consisting of 24 and 7 letters, consonants of demonic writing.

Ancient clues

Determination of the types of Egyptian writing helped the scientist in his further work. But it took him years to determine the correspondence of hieratic and demonic hieroglyphs.

From an inscription in Greek, he knew the place where the name of Ptolemy Epiphanes was engraved, which in Egyptian sounded like Ptolemyos. He found signs corresponding to him in the middle part of the stone. Then he replaced them with hieroglyphs and found the resulting symbols at the top of the stone. He guessed that vowel sounds were often missed, therefore, the name of the pharaoh should sound differently - Ptolmis.

In the winter of 1822 Champollion received another item with inscriptions in Greek and Egyptian. He easily read the name of Queen Cleopatra in the Greek part and found the corresponding signs in the writings of Ancient Egypt.

In a similar way, he wrote other names - Tiberius, Germanicus, Alexander and Domitian. But he was amazed that there were no Egyptian names among them. Then he decided that these were the names of foreign rulers, and phonetic signs were not used for the pharaohs.

It was an incredible discovery. Egyptian writing was sound!

The scientist hastened to inform his brother about his discovery. But, having shouted: "I have found!", I lost consciousness. He lay exhausted for almost a week.

At the end of September Champollion announced his incredible discovery to the French Academy of Sciences. Egyptian hieroglyphs told about the wars and victories of the pharaohs, about the life of people, about the country. The decryption opened a new stage in Egyptology.

The last years of Champollion's life

Champollion - the one who from the scientists was able to decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphs, did not stop there. He went to Italy for new materials, because in this country many Egyptian documents were kept.

Returning from Italy, the scientist published a work describing the grammar of Egypt, containing Egyptian hieroglyphs, the decoding of which became the work of his life.

In 1822 Champollion led an expedition to the land of the pyramids. This was his old dream. He was amazed at the grandeur of the Temple of Hatshepsut, Dendera and Sakkar. He read the inscriptions on their walls with ease.

Returning from Egypt, the scientist was elected to the French Academy. He received universal acclaim. But he did not enjoy fame for very long. The only scientist who managed to decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphs died in March 1832. Thousands of people came to say goodbye to him. He was buried in the Pere Lachaise cemetery.

Egyptian alphabet

A year after the death of the scientist, his brother published his last works containing Egyptian hieroglyphs with translation.

In the beginning, Egyptian writing boiled down to a simple sketch of objects. That is, the whole word was depicted in one picture. Then the drawing began to contain the sounds that make up the word. But the ancient Egyptians did not write vowels. Therefore, different words were often depicted with one hieroglyph. To distinguish them, special qualifiers were placed near the symbol.

The writing of Ancient Egypt consisted of verbal, sound and identifying signs. Sound symbols consisted of several consonants. There were only 24 hieroglyphs, consisting of one letter. They made up the alphabet and were used to write foreign names. All this became known after the mystery of the Egyptian hieroglyphs was solved.

Scribes of Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians used papyri to write. The stems of the plant were cut lengthwise and laid so that their edges overlap a little. In this way, several layers were lined and compressed. Parts of the plant were glued together using their own juice.

The inscriptions were made with pointed sticks. Each scribe had his own sticks. The letters were done in two colors. Black ink was used for the body text, and red was used only at the beginning of the line.

Scribes were trained in schools. It was a prestigious profession.

Champollion's case is alive

When the one who deciphered the Egyptian hieroglyphs died, he worried about continuing to study the culture of Ancient Egypt. In our time, this direction has emerged as a separate science. Literature, religion, and the history of this civilization are being studied now.

So we answered the question of which of the scientists was able to decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphs. Today modern researchers are free to work with primary sources. Thanks to Champollion, the mysterious world of ancient civilization lifts the veil of its secrets every year.

Patron saint of ancient Egyptian writing

Revered by the Egyptians as the patron saint of writing. He was called "the scribe of the gods." The people of Ancient Egypt believed that he invented the alphabet.

In addition, he made many discoveries in the fields of astrology, alchemy and medicine. Plato attributed him to the heirs of the Atlantean civilization, explaining by this his incredible knowledge.

In the XIX century. a strange way of writing biographies has taken root. Authors, the compilers of these biographies zealously sought out and informed their readers facts such as, for example, that the three-year-old Descartes, having seen the bust of Euclid, exclaimed: "Ah!"; or carefully collected and studied Goethe bills for washing clothes, trying and in a bunch of frills and cuffs see the signs of genius.The first example only testifies to a gross methodological miscalculation, the second is simply absurdity, but both are a source of anecdotes, and what, in fact, can you object to anecdotes? After all, even the story about three-year-old Descartes is worthy of a sentimental story, unless, of course, count on those who stay twenty-four hours a day in absolutely serious mood. So, let's put our doubts aside and talk about the amazing birth of Champollion.

In the middle of 1790. Jacques Champollion, bookseller in a small town Figeac in France, called to his completely paralyzed wife - all doctors turned out to be powerless - a local sorcerer, a certain Jacques. The sorcerer ordered to put the patient on the heated herbs, made her drink hot wine and, announcing that she would soon recover, predicted for her - this most of all shocked the whole family - the birth of a boy, who over time will win unfading glory. On the third day, the patient got to her feet. December 23rd 1790 g. at two o'clock in the morning, her son was born - Jean Francois Champollion, - a person who managed to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs. So both came true predictions.

If it is true that children conceived by the devil are born with hooves, then no it is not surprising that the intervention of sorcerers leads to no less noticeable results. The doctor who examined young François with great was surprised to find out that he had a yellow cornea - a feature, inherent in the inhabitants of the East, but extremely rare for Europeans. Moreover, in the boy was unusually dark, almost brown in color and oriental type faces. Twenty years later, he was called the Egyptian everywhere.

“Five years old,” notes one moved biographer, “he carried out his first decoding: comparing what he had learned by heart with printed, he himself learned to read. "At the age of seven, he first heard the magic word "Egypt" in connection with the supposed, but not realized plan of participation of his elder brother Jacques-Joseph in the Egyptian expedition of Napoleon.

In Figeac, he studied, according to eyewitnesses, poorly. Because of this, in 1801, his brother, a gifted philologist who was very interested in archeology, takes the boy to his place in Grenoble and takes care of his upbringing.

When soon the eleven-year-old François shows amazing knowledge of Latin and Greek and makes amazing progress in the study of Hebrew, his brother, also a man of brilliant abilities, as if anticipating that the younger one would ever glorify his family name, decides henceforth to be modestly called Champollion-Figeac; later he was simply called Figeac.

In the same year, Fourier spoke with young François. The famous physicist and mathematician Joseph Fourier took part in the Egyptian campaign, was the secretary of the Egyptian Institute in Cairo, the French commissioner under the Egyptian government, the head of the judicial department and the soul of the Scientific Commission. Now he was prefect of the department of Ysera and lived in Grenoble, gathering around him the best minds of the city. During one of the school inspections, he got into an argument with François, remembered him, invited him to his place and showed him his Egyptian collection.

The dark-skinned boy, as if spellbound, looks at the papyri, examines the first hieroglyphs on the stone slabs. "Can you read this?" he asks. Fourier shakes his head. "I will read this," little Champollion says confidently (later he will often tell this story), "I will read this when I grow up!"

At the age of thirteen, he begins to study Arabic, Syriac, Chaldean, and then Coptic. Note: whatever he studies, whatever he does, whatever he does, is ultimately connected with the problems of Egyptology. He studies ancient Chinese only in order to try to prove the relationship of this language with ancient Egyptian. He studies texts written in ancient Persian, Pahlavian, Persian - the most distant languages, the most distant material, which only thanks to Fourier got to Grenoble, collects everything he can collect, and in the summer of 1807, seventeen years old, he compiled the first geographical map of Ancient Egypt , the first map from the time of the reign of the pharaohs. The boldness of this work can be appreciated only knowing that Champollion had no sources at his disposal except the Bible and individual Latin, Arabic and Hebrew texts, mostly fragmentary and distorted, which he compared with Coptic, for this was the only language that could serve as a kind of bridge to the language of Ancient Egypt and which was known because in Upper Egypt it was spoken in it until the 17th century.

At the same time, he collects material for the book and decides to move to Paris, but the Grenoble Academy wants to receive the final work from him. Gentlemen, the academicians had in mind the usual purely formal speech, Champollion presents a whole book - "Egypt under the Pharaohs" ("L" Egypte sous les Pharaons "). On September 1, 1807, he reads the introduction. The result is unusual! a member of the Academy. ”In one day, yesterday's schoolboy turned into an academician.

Champollion goes headlong into his studies. Disdaining all the temptations of Parisian life, he burrows into libraries, runs from institute to institute, studies Sanskrit, Arabic and Persian. He is so imbued with the spirit of the Arabic language that his voice even changes, and in one company an Arab, mistaking him for a compatriot, bows to him and greets him in his native language. His knowledge of Egypt, which he acquired only through his studies, is so deep that it amazes the most famous traveler in Africa at that time, Somini de Manencourt; after one of the conversations with Champollion, he exclaimed in surprise: "He knows the countries about which we had a conversation, as well as I do."

With all this, he is having a tight, desperately tight situation. If not for his brother, who selflessly supported him, he would have died of hunger. He rented for eighteen francs a pitiful shack not far from the Louvre, but very soon became a debtor and turned to his brother, begging him to help; in despair that he cannot make ends meet, he is completely confused when he receives a reply letter in which Figeac says that he will have to sell his library if François cannot cut his expenses. Reduce costs? Even more? But he already has ragged soles, his suit is completely frayed, he is ashamed to appear in society! In the end, he falls ill: the unusually cold and damp Parisian winter gave impetus to the development of the disease from which he was destined to die.

Champollion returned to Grenoble again. On July 10, 1809, he was appointed professor of history at the University of Grenoble. So at the age of 19 he became a professor where he once studied; among his students were those with whom he sat together on a school bench two years ago. Should we be surprised that he was treated unkindly, that he was entangled in a network of intrigues? Especially zealous were the old professors who considered themselves left out, deprived, unfairly offended.

And what ideas did this young professor of history develop! He declared the pursuit of truth to be the highest goal of historical research, and by truth he meant absolute truth, not Bonapartist or Bourbon truth. Proceeding from this, he advocated freedom of science, also understanding by this absolute freedom, and not such, the boundaries of which are determined by decrees and prohibitions and from which prudence is required in all cases determined by the authorities. He demanded the implementation of those principles that were proclaimed in the first days of the revolution, and then betrayed, and from year to year he demanded this more and more decisively. Such beliefs should inevitably lead him to conflict with reality.

At the same time, he is engaged in what is the main task of his life: he delves deeper into the study of the secrets of Egypt, he writes countless articles, works on books, helps other authors, teaches, and suffers with careless students. All this ultimately affects his nervous system, his health. In December 1816, he writes: "My Coptic dictionary is getting thicker every day. The same cannot be said about its compiler, the opposite is true with him."

All this takes place against the backdrop of dramatic historical events. The Hundred Days comes, and then the return of the Bourbons. It was then, dismissed from the university, exiled as a state criminal, Champollion proceeds to the final deciphering of the hieroglyphs.

The exile lasts a year and a half. This is followed by further tireless work in Paris and Grenoble. Champollion is threatened with a new trial, again on charges of high treason. In July 1821 he left the city, where he went from a schoolboy to an academician. A year later, his work "A Letter to Mr. Dassier regarding the alphabet of phonetic hieroglyphs ..." is published - a book that sets out the basics of deciphering hieroglyphs; she made his name known to everyone who turned their eyes to the land of pyramids and temples, trying to unravel its secrets.

In those years, hieroglyphs were seen as kabbalistic, astrological and gnostic secret teachings, agricultural, commercial and administrative-technical guidelines for practical life; whole passages from the Bible and even from the literature of the times before the flood, Chaldean, Hebrew and even Chinese texts were "read" from hieroglyphic inscriptions. In hieroglyphs, they saw primarily drawings, and only at the moment when Champollion decided that hieroglyphic drawings were letters (more precisely, designations of syllables), a turn came, and this new path was supposed to lead to deciphering.

Champollion, who owned a dozen ancient languages and thanks to his knowledge of Coptic more than anyone else, who came closer to understanding the very spirit of the language of the ancient Egyptians, did not engage in guessing individual words or letters, but figured out the system itself. He did not confine himself to only one interpretation: he strove to make these writings understandable both for study and for reading.

Viewed in retrospect, all great ideas seem simple. Today we know how infinitely complex the hieroglyphic system is. Today the student takes for granted what was not yet known in those days, studies what Champollion, based on his first discovery, obtained through hard work. Today we know what changes hieroglyphic writing underwent in its development from ancient hieroglyphs to cursive forms of the so-called hieratic writing, and later to the so-called demotic writing - an even more abbreviated, even more polished form of Egyptian cursive; the modern scientist Champollion did not see this development. The discovery that helped him to reveal the meaning of one inscription turned out to be inapplicable to another. Who of today's Europeans is able to read a twelfth century handwritten text, even if this text is written in one of the modern languages? And in the ornamented drop cap of any medieval document, a reader who does not have any special training does not recognize the letter at all, although no more than ten centuries separate us from these texts, which belong to a familiar civilization. A scientist who studied hieroglyphs, however, had a deal with an alien, unknown civilization and with a writing that had been developing over three millennia.

It is not always given to an armchair scientist to personally verify the correctness of his theories through direct observation. Often he does not even manage to visit the places where he has been mentally for decades. Champollion was not destined to supplement his outstanding theoretical research with successful archaeological excavations. But he managed to see Egypt, and he was able, through direct observation, to be convinced of the correctness of everything that he changed his mind about in his solitude. Champollion's expedition (it lasted from July 1828 to December 1829) was truly his triumphal procession.

Champollion passed away three years later. His death was a premature loss for the young science of Egyptology. He died too early and did not see full recognition of his merits. Immediately after his death, a number of shameful, offensive works appeared, in particular in English and German, in which his decryption system, despite the very obvious positive results, was declared a product of pure fantasy. However, it was brilliantly rehabilitated by Richard Lepsius, who in 1866 found the so-called Canopic Decree, which fully confirmed the correctness of Champollion's method. Finally, in 1896, the Frenchman Le Page Renouf, in a speech to the Royal Society in London, gave Champollion the place he deserved - this was done sixty-four years after the scientist's death.

Jean-François Champollion; (December 23, 1790 - March 4, 1832) - the great French orientalist and linguist historian, the recognized founder of Egyptology. further development of Egyptology as a science.

Jean-François Champollion was born on December 23, 1790 in the town of Figeac in Dauphiné (modern Law Department) and was the youngest of seven children, two of whom died in infancy, before his birth. Interest in ancient history in the wake of the increased attention to Ancient Egypt after the Egyptian campaign of Napoleon Bonaparte 1798-1801 was developed by his brother, archaeologist Jacques-Joseph Champollion-Figeac.

Jean-François Champollion took up early independent research, taking advantage of the advice of Sylvester de Sacy. As a child, Champollion demonstrated an ingenious ability to learn languages. By the age of 16, he had studied 12 languages and presented to the Grenoble Academy his scientific work "Egypt under the Pharaohs" ("L'Egypte sous les Pharaons", published in 1811), in which he showed a thorough knowledge of the Coptic language. In his 20s, he was fluent in French, Latin, Ancient Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Coptic, Zend, Pahlavi, Syriac, Aramaic, Farsi, Amharic, Sanskrit, and Chinese.

At the age of 19 on July 10, 1809 Champollion becomes professor of history at Grenoble. Champollion's brother, Jacques-Joseph Figeac, was a zealous Bonapartist and after the return of Napoleon Bonaparte from the island of Elba he was appointed personal secretary of the emperor. On entering Grenoble on March 7, 1815, Napoleon met with the Champollion brothers and became interested in Jean-François's research. Despite the fact that Napoleon had to solve important military-political problems, he once again personally visited the young Egyptologist in the local library and continued the conversation about the languages of the Ancient East.

Champollion lost the professorship he received in Grenoble after the restoration of the Bourbons in 1815 as a Bonapartist and an opponent of the monarchy. Moreover, for his participation in the organization of the "Delphic Union" he was exiled for a year and a half. Deprived of the means to live in Grenoble, in 1821 he moved to Paris.

He took an active part in the search for a key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs, interest in which increased after the discovery of the Rosetta stone - a slab with a gratitude inscription of the priests to Ptolemy V Epiphanes, dated 196 BC. NS. For 10 years, he tried to determine the correspondence of hieroglyphs to the modern Coptic language, derived from Egyptian, based on the research of the Swedish diplomat David Johan Okerblat. Eventually, Champollion was able to read the hieroglyphs circled in a cartouche for the names Ptolemy and Cleopatra, but his further progress was hampered by the prevailing belief that phonetic notation was used only in the Late Kingdom or Hellenistic period to designate Greek names. However, he soon came across cartouches with the names of the pharaohs Ramses II and Thutmose III, who ruled in the New Kingdom. This allowed him to put forward an assumption about the predominant use of Egyptian hieroglyphs not to designate words, but to designate consonants and syllables.

In his work Lettre à Mr. Dacier relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques "(1822) Champollion summarized his first studies in the field of deciphering hieroglyphs, and the appearance of his next work" Précis du système hiérogl. d. anciens Egyptiens ou recherches sur les élèments de cette écriture ”(1824) was the beginning of the existence of Egyptology. Champollion's work was actively supported and promoted by his teacher Sylvester de Sacy, the indispensable secretary of the Academy of Inscriptions, who himself had previously failed in his attempt to decipher the Rosetta Stone.

Around the same time, Champollion systematized Egyptian mythology on the basis of the new material received ("Panthéon égyptien"), and also studied the collections of Italian museums, drawing the attention of the scientific community to the Turin royal papyrus ("Deux lettres à M. le duc de Blacas d'Aulps relatives au musée royal de Turin, formant une histoire chronologique des dynasties égyptiennes "; 1826).

In 1826 Champollion was commissioned to organize the first museum specializing in Egyptian antiquities, and in 1831 he was given the first chair of Egyptology. In 1828-1829, together with the Italian linguist Ippolito Rosellini, he made his first expedition to Egypt and Nubia. During the expedition, he studied a huge number of ancient Egyptian monuments and inscriptions, fruitfully worked on the collection and research of epigraphic and archaeological material.

During a business trip to Egypt, Champollion finally undermined his poor health and died in Paris as a result of an apoplectic stroke at the age of only 41 (1832), without having time to systematize the results of his expedition, published after Champollion's death in four volumes under the title "Monuments de l'Egypte et de la Nubie "(1835-1845) and two volumes" Notices descriptives conformes aux manuscrits autographes rédigés sur les lieux par Champollion le jeunes "(1844). Champollion's main linguistic work, Grammaire Égyptienne, was also published after the death of the author by order of the Minister of Education Guizot. Champollion is buried in the Pere Lachaise cemetery.