Chronology of events of the Mongol conquests of Russia 1480. Tatar-Mongol yoke

Read also

N A SH K A L E N D A R b

November 24, 1480 - the end of the Tatar-Mongol yoke in Russia

In the distant fifties, the author of this article, then a graduate student of the State Hermitage, took part in archaeological excavations in the city of Chernigov. When we reached the layers of the middle of the 13th century, terrible pictures of the traces of Batu's invasion of 1239 were revealed before our eyes.

The Ipatiev Chronicle under. 1240 describes the assault on the city in this way: “Surrounding the city of Chernigov (“ Tartar ”- BS), the city of Chernigov is heavy in strength .. Prince Mikhail Glebovich came on foreign tribes with his warriors, and there was a battle at Chernigov ... But Mstislav was defeated and many from howl (soldiers - B.S.) were beaten by him. And the hail took and ignited with fire ... ”. Our excavations have confirmed the accuracy of the chronicle record. The city was ravaged and burned to the ground. A ten-centimeter layer of ash covered the entire area of one of the richest cities in Ancient Russia. Fierce battles were fought for every house. The roofs of houses often bore the marks of the blows of heavy stones from Tatar catapults, the weight of which reached 120-150 kg (The annals indicate that these stones could barely lift four strong people.) The inhabitants were either killed or taken prisoner. The ashes of the burnt city were mixed with the bones of thousands of dead people.

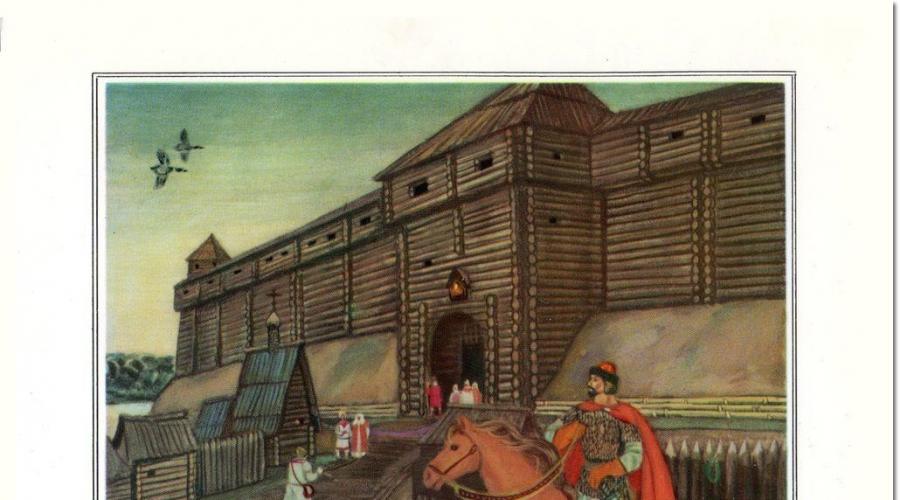

After completing my postgraduate studies, already as a research fellow at the museum, I worked on the creation of a permanent exhibition "Russian culture of the 6th-13th centuries." In the process of preparing the exposition, special attention was paid to the fate of a small ancient Russian fortress city, erected in the 12th century. on the southern borders of Ancient Rus, near the modern city of Berdichev, now called Raiki. To some extent, his fate is close to the fate of the world famous ancient Italian city of Pompeii, destroyed in 79 AD. during the eruption of Vesuvius.

But Raiki were completely destroyed not by the forces of the raging elements, but by the hordes of Khan Batu. The study of material material stored in the State Hermitage Museum, and written reports on excavations made it possible to restore a terrible picture of the death of the city. It reminded me of the pictures of Belarusian villages and cities burned by the invaders, seen by the author during our offensive during the Great Patriotic War, in which the author took part. The inhabitants of the city resisted desperately and all died in an unequal struggle. Dwelling houses were excavated, on the thresholds of which there were two skeletons - a Tatar and a Russian, killed with a sword in his hand. There were terrible scenes - the skeleton of a woman covering her child with her body. A Tatar arrow is stuck in her vertebrae. After the defeat, the city did not come to life, and everything remained in the same form as the enemy left it.

Hundreds of Russian cities shared the tragic fate of Raikov and Chernigov.

The Tatars destroyed about a third of the entire population of Ancient Rus. Considering that at that time about 6 - 8,000,000 people lived in Russia, at least 2,000,000 - 2,500,000 were killed. Foreigners passing through the southern regions of the country wrote that Russia was practically turned into a dead desert, and such a state was on the map Europe no longer exists. The horrors of the Tatar-Mongol invasion are described in detail in Russian chronicles and literary sources, such as "The Word about the Destruction of the Russian Land", "The Tale of the Ruin of Ryazan" and others. The tragic consequences of Batu's campaigns were largely multiplied by the establishment of an occupation regime, which not only led to the total plundering of Russia, but drained the soul of the people. He delayed the forward movement of our Motherland for more than 200 years.

The Great Battle of Kulikovo in 1380 inflicted a decisive defeat on the Golden Horde, but could not completely destroy the yoke of the Tatar khans. The Grand Dukes of Moscow were faced with the task of completely, legally eliminating the dependence of Russia on the Horde.

November 24 of the new style (11 old) on the church calendar marks a remarkable date in the history of our Motherland. 581 years ago, in 1480 - the “Standing on the Ugra” ended. The Golden Horde Khan Akhma (? - 1481) turned his fogs away from the borders of the Grand Duchy of Moscow and was soon killed.

This was the legal end of the Mongol-Tatar yoke. Russia became a completely sovereign state.

Unfortunately, neither the media, nor in the minds of the general public, this date was not reflected. Meanwhile, it is quite obvious that on that day the dark page of our history was turned over, and a new stage in the independent development of the Fatherland began.

It is necessary, at least briefly, to recall the development of events in those years.

Although the last khan of the Great Horde stubbornly continued to consider the Grand Duke of Moscow his tributary, in fact, Ivan Sh Vasilyevich (reigned 1462 - 1505) was actually independent of the khan. Instead of a regular tribute, he sent small gifts to the Horde, the size and regularity of which he himself determined. The Horde began to understand that the times of Batu were gone forever. The Grand Duke of Moscow became a formidable adversary, not a silent slave.

In 1472, the Khan of the Big (Golden) Horde, at the suggestion of the Polish king Casimir IV, who had promised him support, undertook the usual campaign for the Tatars against Moscow. However, it ended in complete failure for the Horde. They could not even cross the Oka, which was the traditional defensive line of the capital.

In 1476, the Khan of the Great Horde sent an embassy to Moscow, headed by Akhmet Sadyk, with a formidable demand to fully restore tributary relations. In Russian written sources, in which legends and reports of true facts were complexly intertwined, the negotiations were complex. During the first stage, Ivan III, in the presence of the Boyar Duma, was playing for time, realizing that a negative answer meant war. It is likely that Ivan III made the final decision under the influence of his wife Sophia Fominichna Palaeologus, a proud Byzantine princess, who allegedly told her husband with anger: “I married the Grand Duke of Russia, not a Horde servant.” At the next meeting with the ambassadors, Ivan III changed his tactics. He tore up the khan's letter and trampled the basma with his feet (a basma or paiza-box filled with wax with the imprint of the khan's heel was issued to the ambassadors as a credential). And the ambassadors themselves were expelled from Moscow. Both in the Horde and in Moscow it became clear that a large-scale war was inevitable.

But Akhmat did not go straight to action. In the early eighties, Casimir IV began to prepare for war with Moscow. The traditional alliance of the Horde and the Polish crown against Russia was outlined. The situation in Moscow itself was aggravated. At the end of 1479 there was a quarrel between the Grand Duke and his brothers Boris and Andrey Bolshoi. They rose from their estates with their families and "courtyards" and headed through the Novgorod lands to the Lithuanian border. There was a real threat of unification of the internal separatist opposition with the attack of external enemies - Poland and the Horde.

Given this circumstance, Khan Akhmat decided that the time had come to strike a decisive blow, which should be supported by the invasion of the Russian borders by the Polish-Lithuanian troops. Gathering a huge army, the Khan of the Great Horde at the end of the spring of 1480, when the grass, necessary for the food of his cavalry, turned green, moved to Moscow. But not directly to the North, but bypassing the capital, from the southwest, to the upper reaches of the Oka, towards the Lithuanian border to join with Casimir IV. In the summer, the Tatar hordes reached the right bank of the Ugra River, not far from its confluence with the Oka (Modern Kaluga Region). About 150 km remained to Moscow.

For his part, Ivan III took decisive measures to strengthen his position. His special services established contact with the enemy of the Great Horde - the Crimean Khan Mengly-Girey, who attacked the southern regions of Lithuania and thereby prevented Casimir IV from coming to the aid of Akhmat. Towards the Horde, Ivan III moved his main forces, which approached the northern left bank of the Ugra, covering the capital.

In addition, the Grand Duke sent an auxiliary corps by water along the Volga to the capital of the Horde - the city of Sarai. Taking advantage of the fact that the main forces of the Horde were on the banks of the Ugra, the Russian troops defeated it, and, according to legend, plowed the ruins of the city, as a sign that there will never be a threat to Russia from this place (now the village of Selitryany is located on this place) ...

On the banks of a small river, two huge troops converged. The so-called "Standing on the Ugra" began, when both sides did not dare to start a general battle. Akhmat waited in vain for the help of Casimir, and Ivan had to deal with his brothers. As an extremely cautious person, the Grand Duke took decisive action only when he was confident of victory.

Several times the Tatars tried to cross the Ugra, but met with powerful fire from Russian artillery, commanded by the famous Italian architect Aristotle Fiorovanti, the builder of the Assumption Cathedral in 1479, were forced to retreat.

At this time, Ivan III, having abandoned his troops, returned to Moscow, which caused unrest in the capital, since the threat of a breakthrough by the Tatar troops was not eliminated. The inhabitants of the capital demanded active action, accusing the Grand Duke of indecision.

The Rostov Archbishop Vassian in the famous "Epistle to the Ugra" called the Grand Duke a "runner" and called on him to "harrow his fatherland." But Ivan's caution is understandable. He could not start a decisive battle without a reliable rear. In Moscow, with the assistance of church hierarchs, on October 6, he made peace with his brothers, and their retinues joined the grand ducal army.

Meanwhile, the favorable situation for Akhmat has changed dramatically. Busy with the defense of the southern borders, the Polish-Lithuanian troops never came to the aid of Akhmat. Strategically, the khan had already lost the battle that had not taken place. Time passed towards autumn. Winter was approaching, the Ugra River froze over, which made it possible for the Tatars to easily cross to the other side. Accustomed to warm winters on the shores of the Black and Azov Seas, the Tatars were worse than the Russians withstanding the coming cold.

In mid-November, Ivan III gave the command to move to winter apartments in Borovsk, located 75 km from Moscow. On the banks of the Ugra, he left the “watchman” to observe the Tatars. Further events developed according to a scenario that no one in the Russian camp could have foreseen. On the morning of November 11, the old style - 24 new, the guards unexpectedly saw that the right bank of the Ugra was empty. The Tatars secretly withdrew from their positions at night and went south. The swiftness and good disguise of the retreat of the Khan's troops were perceived by the Russians as a flight that they did not expect.

Ivan III Vasilievich, Grand Duke of Moscow and All Russia, returned to Moscow as a winner.

Khan Akhmat, who had no reason to return to the burnt Sarai, went to the lower reaches of the Volga, where on January 6, 1481 he was killed by the Nogai Tatars.

So the Tatar-Mongol yoke was eliminated, which brought innumerable calamities to our people.

November 24 of the new style is one of the most significant dates of the Patriotic history, the memory of which cannot fade into centuries.

The question of the date of the beginning and end of the Tatar-Mongol yoke in Russian historiography as a whole did not cause controversy. In this small post, he will try to dot the i's in this matter, at least for those who are preparing for the exam in history, that is, within the framework of the school curriculum.

The concept of the "Tatar-Mongol yoke"

However, first it is worth dealing with the very concept of this yoke, which is an important historical phenomenon in the history of Russia. If we turn to ancient Russian sources ("The Tale of the Ruin of Ryazan by Batu", "Zadonshchina", etc.), then the invasion of the Tatars is perceived as a given by God. The very concept of "Russian land" disappears from the sources and other concepts arise: "Horde Zalesskaya" ("Zadonshchina"), for example.

The very same "yoke" was not called that word. The words "captivity" are more common. Thus, within the framework of the medieval providential consciousness, the invasion of the Mongols was perceived as an inevitable punishment of the Lord.

Historian Igor Danilevsky, for example, also believes that this perception is due to the fact that, due to their negligence, the Russian princes in the period from 1223 to 1237: 1) did not take any measures to protect their lands, and 2) continued to maintain a fragmented state and create civil strife. It is for fragmentation that God punished the Russian land - in the minds of his contemporaries.

The very concept of "Tatar-Mongol yoke" was introduced by N.M. Karamzin in his monumental work. From this, by the way, he deduced and substantiated the need for an autocratic form of government in Russia. The emergence of the concept of yoke was necessary in order, firstly, to substantiate Russia's lag behind European countries, and, secondly, to substantiate the need for this Europeanization.

If you look at different school textbooks, the dating of this historical phenomenon will be different. However, it often dates from 1237 to 1480: from the beginning of Batu's first campaign against Russia and ending with Standing on the Ugra River, when Akhmat Khan left and thereby tacitly recognized the independence of the Moscow state. In principle, this is a logical dating: Batu, having seized and defeated Northeastern Russia, has already subjugated part of the Russian lands to himself.

However, in my studies, I always determine the date of the beginning of the Mongol yoke in 1240 - after the second campaign of Batu, already to South Russia. The meaning of this definition is that then the entire Russian land was subordinated to Batu and he had already imposed duties on it, arranged Baskaks in the occupied lands, etc.

If you think about it, the date of the beginning of the yoke can also be determined as 1242 - when Russian princes began to come to the Horde with gifts, thereby recognizing their dependence on the Golden Horde. Quite a few school encyclopedias place the date of the beginning of the yoke under this year.

The date of the end of the Mongol-Tatar yoke is usually placed in 1480 after the Standing on the river. Eel. However, it is important to understand that for a long time the Muscovy was disturbed by the "fragments" of the Golden Horde: the Kazan Khanate, the Astrakhan, the Crimean ... The Crimean Khanate was completely liquidated in 1783. Therefore, yes, we can talk about formal independence. But with reservations.

Best regards, Andrey Puchkov

The history of Russia has always been a bit sad and turbulent due to wars, power struggles and drastic reforms. These reforms were often blamed on Russia at once, forcibly, instead of introducing them gradually, measuredly, as has often happened in history. Since the first mention of the princes of different cities - Vladimir, Pskov, Suzdal and Kiev - constantly fought and argued for power and control over a small semi-united state. Under the rule of Saint Vladimir (980-1015) and Yaroslav the Wise (1015-1054)

The Kiev state was at the pinnacle of prosperity and achieved a relative peace, unlike in previous years. However, as time went on, the wise rulers died, and the struggle for power began again and wars broke out.

Before his death, in 1054, Yaroslav the Wise decided to divide the principalities between his sons, and this decision determined the future of Kievan Rus for the next two hundred years. Civil wars between the brothers ruined most of the Kiev community of cities, depriving it of the necessary resources that would be very useful to it in the future. When the princes continuously fought with each other, the former Kiev state slowly disintegrated, diminished and lost its former glory. At the same time, it was weakened by the invasions of the steppe tribes - the Polovtsy (they are the Cumans or Kipchaks), and before that the Pechenegs, and in the end the Kiev state became an easy prey for more powerful invaders from distant lands.

Russia had a chance to change its fate. Around 1219, the Mongols first entered the regions near Kievan Rus, heading for, and they asked for help from the Russian princes. A council of princes gathered in Kiev to consider the request, which greatly disturbed the Mongols. According to historical sources, the Mongols stated that they were not going to attack Russian cities and lands. The Mongol envoys demanded peace with the Russian princes. However, the princes did not trust the Mongols, suspecting that they would not stop and go to Russia. Mongol ambassadors were killed, and thus the chance for peace was destroyed by the hands of the princes of the divided Kiev state.

For twenty years, Batu Khan with an army of 200 thousand people made raids. One after another, the Russian principalities - Ryazan, Moscow, Vladimir, Suzdal and Rostov - fell into bondage to Batu and his army. The Mongols plundered and destroyed the cities, the inhabitants were killed or taken prisoner. In the end, the Mongols captured, plundered and razed to the ground Kiev, the center and symbol of Kievan Rus. Only remote northwestern principalities such as Novgorod, Pskov and Smolensk survived the onslaught, although these cities will endure indirect submission and become appendages of the Golden Horde. Perhaps, by concluding peace, the Russian princes could have prevented this. However, this cannot be called a miscalculation, because then Russia would forever have to change religion, art, language, system of government and geopolitics.

Orthodox Church during the Tatar-Mongol yoke

The first Mongol raids looted and destroyed many churches and monasteries, and countless priests and monks were killed. Those who survived were often captured and sent into slavery. The size and power of the Mongol army was shocking. Not only the economy and political structure of the country suffered, but also social and spiritual institutions. The Mongols claimed that they were God's punishment, and the Russians believed that all this was sent to them by God as a punishment for their sins.

The Orthodox Church will become a powerful beacon in the "dark years" of Mongol dominance. The Russian people eventually turned to the Orthodox Church, seeking consolation in their faith and guidance and support from the clergy. The raids of the steppe people caused a shock, throwing seeds on fertile soil for the development of Russian monasticism, which in turn played an important role in the formation of the worldview of neighboring Finno-Ugric and Zyrian tribes, and also led to the colonization of the northern regions of Russia.

The humiliation suffered by the princes and city authorities undermined their political authority. This allowed the church to become the embodiment of religious and national identity, filling in the lost political identity. The unique legal concept of the label, or charter of immunity, also helped strengthen the church. During the reign of Mengu-Timur in 1267, a label was issued to Metropolitan Kirill of Kiev for the Orthodox Church.

Although the church de facto came under the protection of the Mongols ten years earlier (from the 1257 census conducted by Khan Berke), this label officially recorded the inviolability of the Orthodox Church. More importantly, he officially exempted the church from any form of taxation by the Mongols or the Russians. Priests had the right not to register during censuses and were exempted from forced labor and military service.

As expected, the label issued to the Orthodox Church has taken on a lot of significance. For the first time, the church becomes less dependent on the princely will than in any other period of Russian history. The Orthodox Church was able to acquire and secure for itself significant tracts of land, which gave it an extremely strong position that continued for centuries after the Mongol conquest. The charter strictly prohibited both Mongolian and Russian tax agents from seizing church lands or demanding anything from the Orthodox Church. This was guaranteed by a simple punishment - death.

Another important reason for the rise of the church lay in its mission - to spread Christianity and to convert the village pagans to their faith. Metropolitans traveled extensively throughout the country to strengthen the internal structure of the church and to solve administrative problems and control the activities of bishops and priests. Moreover, the relative safety of the sketes (economic, military and spiritual) attracted the peasants. As the rapidly growing cities interfered with the atmosphere of goodness that the church provided, the monks began to leave for the deserts and rebuild monasteries and hermitages there. Religious settlements continued to be built and thereby strengthened the authority of the Orthodox Church.

The last significant change was the relocation of the center of the Orthodox Church. Before the Mongols invaded the Russian lands, Kiev was the church center. After the destruction of Kiev in 1299, the Holy See moved to Vladimir, and then, in 1322 to Moscow, which significantly increased the importance of Moscow.

Fine arts during the Tatar-Mongol yoke

While mass deportations of artists began in Russia, monastic revival and attention to the Orthodox Church led to an artistic revival. What brought Russians together in that difficult time, when they found themselves without a state, is their faith and ability to express their religious beliefs. During this difficult time, the great artists Theophanes the Greek and Andrei Rublev worked.

It was during the second half of Mongol rule in the mid-fourteenth century that Russian iconography and fresco painting began to flourish again. Theophanes the Greek arrived in Russia at the end of the 1300s. He painted churches in many cities, especially in Novgorod and Nizhny Novgorod. In Moscow, he painted the iconostasis for the Church of the Annunciation, and also worked on the church of the Archangel Michael. A few decades after the arrival of Theophan, the beginner Andrei Rublev became one of his best students. Iconography came to Russia from Byzantium in the 10th century, but the Mongol invasion in the 13th century cut off Russia from Byzantium.

How the language changed after the yoke

It may seem insignificant to us such an aspect as the influence of one language on another, but this information helps us to understand to what extent one nationality influenced another or a group of nationalities - on state administration, on military affairs, on trade, as well as how it was geographically distributed. influence. Indeed, the linguistic and even sociolinguistic influences were great, as the Russians borrowed thousands of words, phrases, and other significant linguistic constructs from the Mongolian and Turkic languages, united into the Mongol Empire. Listed below are a few examples of words that are still used today. All borrowings came from different parts of the Horde:

- barn

- bazaar

- money

- horse

- box

- customs

One of the very important colloquial features of the Russian language of Turkic origin is the use of the word “come on”. Listed below are a few common examples that are still found in Russian.

- Let's have some tea.

- Let's have a drink!

- Let's go!

In addition, in the south of Russia there are dozens of local names of Tatar / Turkic origin for lands along the Volga, which are highlighted on the maps of these regions. Examples of such names: Penza, Alatyr, Kazan, regional names: Chuvashia and Bashkortostan.

Kievan Rus was a democratic state. The main governing body was the veche - a meeting of all free male citizens who gathered to discuss such issues as war and peace, law, invitation or expulsion of princes to the respective city; all cities in Kievan Rus had veche. It was, in fact, a forum for civil affairs, for discussing and solving problems. However, this democratic institution was severely curtailed under the rule of the Mongols.

By far the most influential gatherings were in Novgorod and Kiev. In Novgorod, a special veche bell (in other cities, church bells were usually used for this) served to summon the townspeople, and, theoretically, anyone could ring it. When the Mongols conquered most of Kievan Rus, the Veche ceased to exist in all cities except Novgorod, Pskov and several other cities in the northwest. Veche in these cities continued to work and develop until Moscow subdued them at the end of the 15th century. However, today the spirit of the veche as a public forum has been revived in several cities of Russia, including Novgorod.

The population censuses, which made it possible to collect tribute, were of great importance for the Mongol rulers. To support the censuses, the Mongols introduced a special dual system of regional administration, headed by military governors, Baskaks and / or civilian governors, Darugachs. In fact, the Baskaks were responsible for directing the activities of rulers in areas that resisted or did not accept Mongol rule. The Darugachi were civilian governors who controlled those areas of the empire that surrendered without a fight or that were considered already submissive to the Mongol forces and calm. However, the Baskaki and Darugachi sometimes performed the duties of the authorities, but did not duplicate it.

As is known from history, the ruling princes of Kievan Rus did not trust the Mongol ambassadors, who came to make peace with them in the early 1200s; the princes, sadly, betrayed Genghis Khan's ambassadors to the sword and soon paid dearly. Thus, in the 13th century, Baskaks were placed on the conquered lands to subjugate the people and control even the daily activities of the princes. In addition, in addition to conducting the census, the Baskaks provided recruiting for the local population.

Existing sources and research show that the Baskaks largely disappeared from the Russian lands by the middle of the 14th century, as Russia more or less recognized the rule of the Mongol khans. When the Baskaks left, power passed to the Darugachs. However, unlike the Baskaks, the Darugachi did not live on the territory of Russia. In fact, they were in Sarai, the old capital of the Golden Horde, located not far from present-day Volgograd. Darugachi served in the lands of Russia mainly as advisers and consulted the khan. Although the responsibility for collecting and delivering tribute and conscripts belonged to the Baskaks, with the transition from the Baskaks to the Darugachs, these responsibilities were actually transferred to the princes themselves, when the khan saw that the princes were quite coping with this.

The first census carried out by the Mongols took place in 1257, just 17 years after the conquest of Russian lands. The population was divided into dozens - the Chinese had such a system, the Mongols adopted it, using it throughout their empire. The main purpose of the census was conscription as well as taxation. Moscow continued this practice after it stopped recognizing the Horde in 1480. The practice attracted foreign visitors to Russia, for whom large-scale censuses were still unknown. One such visitor, Sigismund von Herberstein of Habsburg, noted that every two or three years the prince carried out a census all over the earth. The population census was not widely disseminated in Europe until the early 19th century. One significant remark that we must make: the thoroughness with which the Russians carried out the census could not have been achieved in other parts of Europe in the era of absolutism for about 120 years. The influence of the Mongol Empire, at least in this area, was obviously deep and effective and helped to create a strong centralized government for Russia.

One of the important innovations that the Baskaks oversaw and supported were the pits (a system of posts), which were built to provide travelers with food, lodging, horses, and carts or sledges, depending on the season. Originally built by the Mongols, the yam ensured the relatively rapid movement of important dispatches between the khans and their governors, as well as the rapid dispatch of envoys, local or foreign, between the various principalities throughout the vast empire. At each post there were horses to carry authorized persons, as well as to replace tired horses on especially long journeys. Each post, as a rule, was located about a day's drive from the nearest post. Local residents were required to support the caretakers, feed the horses, and meet the needs of officials traveling on business.

The system was efficient enough. Another report by Sigismund von Herberstein of Habsburg said that the pit system allowed him to travel 500 kilometers (from Novgorod to Moscow) in 72 hours - much faster than anywhere else in Europe. The pit system helped the Mongols maintain tight control over their empire. During the gloomy years of the Mongols in Russia at the end of the 15th century, Prince Ivan III decided to continue using the idea of the pit system in order to preserve the existing system of communications and intelligence. However, the idea of a postal system as we know it today did not emerge until the death of Peter the Great in the early 1700s.

Some of the innovations brought to Russia by the Mongols satisfied the needs of the state for a long time and continued for many centuries after the Golden Horde. This greatly expanded the development and expansion of the complex bureaucracy of later, imperial Russia.

Founded in 1147, Moscow remained an insignificant city for over a hundred years. At that time, this place lay at the crossroads of three main roads, one of which connected Moscow with Kiev. The geographical location of Moscow deserves attention, since it is located at the bend of the Moscow River, which merges with the Oka and Volga. Through the Volga, which allows you to get to the Dnieper and the Don rivers, as well as the Black and Caspian seas, there have always been huge opportunities for trade with neighboring and distant lands. With the advance of the Mongols, crowds of refugees began to arrive from the devastated southern part of Russia, mainly from Kiev. Moreover, the actions of the Moscow princes in favor of the Mongols contributed to the rise of Moscow as a center of power.

Even before the Mongols gave Moscow a label, Tver and Moscow were constantly fighting for power. A major turning point occurred in 1327, when the people of Tver began to revolt. Seeing this as an opportunity to please the khan of his Mongol overlords, Prince Ivan I of Moscow with a huge Tatar army suppressed the uprising in Tver, restoring order in this city and winning the favor of the khan. To demonstrate loyalty, Ivan I was also given a label, and thus Moscow came one step closer to fame and power. Soon the princes of Moscow took on the responsibility of collecting taxes throughout the land (including from themselves), and eventually the Mongols entrusted this task exclusively to Moscow and stopped the practice of sending their tax collectors. Nevertheless, Ivan I was more than a shrewd politician and a model of sanity: he may have been the first prince to replace the traditional horizontal line of succession with a vertical one (although it was fully achieved only by the second reign of Prince Basil in the middle of 1400). This change led to greater stability in Moscow and thus strengthened its position. As Moscow grew by collecting tribute, its power over other principalities was increasingly asserted. Moscow received land, which means it collected more tribute and got more access to resources, and therefore more power.

Even before the Mongols gave Moscow a label, Tver and Moscow were constantly fighting for power. A major turning point occurred in 1327, when the people of Tver began to revolt. Seeing this as an opportunity to please the khan of his Mongol overlords, Prince Ivan I of Moscow with a huge Tatar army suppressed the uprising in Tver, restoring order in this city and winning the favor of the khan. To demonstrate loyalty, Ivan I was also given a label, and thus Moscow came one step closer to fame and power. Soon the princes of Moscow took on the responsibility of collecting taxes throughout the land (including from themselves), and eventually the Mongols entrusted this task exclusively to Moscow and stopped the practice of sending their tax collectors. Nevertheless, Ivan I was more than a shrewd politician and a model of sanity: he may have been the first prince to replace the traditional horizontal line of succession with a vertical one (although it was fully achieved only by the second reign of Prince Basil in the middle of 1400). This change led to greater stability in Moscow and thus strengthened its position. As Moscow grew by collecting tribute, its power over other principalities was increasingly asserted. Moscow received land, which means it collected more tribute and got more access to resources, and therefore more power.

At a time when Moscow was becoming more and more powerful, the Golden Horde was in a state of general decay caused by riots and coups. Prince Dmitry decided to attack in 1376 and succeeded. Soon after, one of the Mongol generals Mamai tried to create his own horde in the steppes west of the Volga, and he decided to challenge the power of Prince Dmitry on the banks of the Vozha River. Dmitry defeated Mamai, which delighted the Muscovites and of course angered the Mongols. However, he collected an army of 150 thousand people. Dmitry gathered an army of comparable size, and these two armies met at the Don River on the Kulikovo field in early September 1380. The Rusichi of Dmitry, although they lost about 100,000 people, won. Tokhtamysh, one of Tamerlane's generals, soon captured and executed General Mamai. Prince Dmitry became known as Dmitry Donskoy. However, Moscow was soon plundered by Tokhtamysh and again had to pay tribute to the Mongols.

But the great battle at Kulikovo Field in 1380 was a symbolic turning point. Despite the fact that the Mongols severely avenged Moscow for its rebelliousness, the power that Moscow showed grew and its influence over other Russian principalities expanded. In 1478, Novgorod finally submitted to the future capital, and Moscow soon threw off its obedience to the Mongol and Tatar khans, thus ending more than 250 years of Mongol rule.

Results of the period of the Tatar-Mongol yoke

Evidence suggests that the multiple effects of the Mongol invasion extended to the political, social, and religious aspects of Rus. Some of them, for example, the growth of the Orthodox Church, had a relatively positive impact on the Russian lands, while others, for example, the loss of the veche and the centralization of power, contributed to the cessation of the spread of traditional democracy and self-government for various principalities. Due to the influence on the language and form of government, the impact of the Mongol invasion is still evident today. Perhaps thanks to the chance to experience the Renaissance, as in other Western European cultures, Russia's political, religious and social thought will be very different from the political reality of today. Under the control of the Mongols, who adopted many of the ideas of government and economics from the Chinese, the Russians became, perhaps, a more Asian country in terms of administrative structure, and the deep Christian roots of the Russians established and helped maintain a connection with Europe. The Mongol invasion, perhaps more than any other historical event, determined the course of the development of the Russian state - its culture, political geography, history and national identity.

There are many rumors around the period of the Tatar-Mongol invasion, and some historians even speak of a conspiracy of silence, which was actively promoted in Soviet times. Around 44 of the last century, for some strange and incomprehensible reason, the studies of this historical time period were completely closed to specialists, that is, they completely stopped. Many retained the official version of history, in which the Horde period was presented as dark and troubled times, when evil invaders brutally exploited the Russian principalities, placing them in vassal dependence. Meanwhile, the Golden Horde had a huge impact on the economy, as well as the culture of Russia, setting aside its development just for the very three hundred years that it ruled and commanded. When the Mongol-Tatar yoke was finally overthrown, the country healed in a new way, and the cause of that was the Grand Duke of Moscow, which will be discussed.

The annexation of the Novgorod Republic: liberation from the Mongol-Tatar yoke began with a small

It is worth saying that the overthrow of the Golden Horde yoke took place under the Moscow prince, or rather Tsar Ivan III Vasilievich, and this process, which lasted more than half a century, ended in 1480. But it was preceded by quite fascinating and amazing events. It all started with the fact that the once great empire built by Genghis Khan and presented to his son, the Golden Horde by the middle of the fourteenth - early fifteenth centuries, began to simply fall apart into pieces, dividing into smaller khanates-ulus, after the death of Khan Janibek. His grandson Isataya tried to unite his lands, but was defeated. The great Khan Tokhtamysh, who came to power after that, a real Chingizid by blood, stopped the turmoil and internal strife, briefly restored its former glory, and again began to terrify the controlled lands of Russia.

Interesting

In the middle of the thirteenth century, Muslim merchants levied tribute from Russian merchants, who were called the beautiful word "desermen". It is interesting that this word has firmly entered the spoken, folk language, and a person who had a different faith, as well as exorbitant "appetites", was called a Basurman for a very long time, and even now you can hear a similar word.

The situation unfolded, meanwhile, was not at all favorable for the Horde, since from all sides the Horde was surrounded and pressed by enemies, giving no sleep or breath. Already in 1347, by order of the Moscow prince Dmitry Ivanovich (Donskoy), payments to the Horde Khan were completely stopped. Moreover, it was they who conceived to unite the Russian lands, but Novgorod stood in the way, together with its free republic. Moreover, the oligarchy, which established its own powerful enough power there, tried to restrain the onslaught, both from Muscovy and the pressure of the dissatisfied masses, the veche device began to gradually lose its relevance. The end of the Mongol-Tatar yoke was already looming on the horizon, but it was still ghostly and vague.

A long campaign to Novgorod: the overthrow of the Golden Horde yoke is a matter of technology and time

It is because of this that the people began to look more and more at Moscow than at their own rulers, and even more so at the Horde who had become weakened by that time. Moreover, the posadnichy reform of 1410 became a turning point and the boyars came to power, pushing the oligarchy into the background. It is clear that the collapse was simply inevitable, and it came when in the early seventies part of the Novgorodians, under the leadership of Boretsky, completely passed under the wing of the Lithuanian prince, this was the last point in Moscow's cup of patience. Ivan III had no choice but to annex Novgorod by force, which he successfully did, gathering under his own banners the army of almost all the lands and lands under his control.

Moscow chroniclers, whose testimonies have been preserved, considered the campaign of the Moscow Tsar to Novgorod a real war for the faith, and, consequently, against the infidels, against the conversion of the Russian lands to Catholicism, and even more so to Islam. The key battle was fought in the lower reaches of the Sheloni River, and most of the Novgorodians, frankly speaking, fought carelessly, since they did not feel much need to defend the oligarchy, and they had no desire.

The archbishop of Novgorod, not an adherent of the Moscow principality, decided to make a knight's move. He wanted to preserve the independent position of his own lands, but hoped to come to an agreement with the Prince of Moscow, and not with the locals, and even more so, not with the Horde. Therefore, his entire regiment most of the time simply stood still, and did not enter the battle. These events also played a large role in the overthrow of the Tatar-Mongol yoke, significantly bringing the end of the Golden Horde closer.

Contrary to the hopes of the archbishop, Ivan III did not want to make compromises and agreements at all, and after the establishment of Moscow power in Novgorod, he radically solved the problem - he destroyed or exiled most of the disgraced boyars to the central part of the country, and simply confiscated the lands that belonged to them. Moreover, the people of Novgorod approved such actions of the tsar, because it was precisely those boyars who did not give life to people that were destroyed, establishing their own rules and orders. In the 1470s, the end of the Tatar-Mongol yoke, due to the turmoil in Novgorod, sparkled with new colors and approached excessively. By 1478 the republic was completely abolished, and even the veche bell was removed from the bell tower and taken to Muscovy. Thus, Novgorod, together with all its lands, became part of Russia, but for some time retained its status and liberties.

Liberation of Russia from the Horde yoke: the date is known even to children

In the meantime, while Russia was forcibly implanting good and light, which in fact was so, the Golden Horde began to be torn apart by petty khans, wanting to tear off a larger piece. Each of them, in words, wanted the reunification of the state, as well as the revival of its former glory, but in reality it turned out somewhat differently. Akhmed Khan, the undivided ruler of the Great Horde, decided to resume campaigns against Russia, to force her to pay tribute again, receiving labels and letters from the khanate for this. For this purpose, he decided to conclude a deal, in fact, to enter into an allied relationship with Casimir IV, king of the Polish-Lithuanian Empire, which he successfully pulled off, without even realizing what it would turn out to be for him.

If we talk about who defeated the Tatar-Mongol yoke in Russia, then the surely correct answer would be the Grand Duke of Moscow, who ruled at that time, as already mentioned, Ivan III. The Tatar-Mongol yoke was overthrown under him, and the unification of many lands under the wing of Ancient Russia was also his work. However, the brothers of the Prince of Moscow did not at all share his views, and in general, they believed that he did not deserve his place at all, therefore they were just waiting for him to take the wrong step.

In political terms, Ivan the Third turned out to be an extremely wise ruler, and at a time when the Horde was experiencing the greatest difficulties, he decided to castling, and made an alliance with the Crimean Khan, named Mengli-Girey, who had his own grudge against Ahmed Khan. The thing is that in 1476, Ivan flatly refused to visit the sovereign of the Great Horde, and he, as if in revenge, captured the Crimea, but after only two years, Mengli-Girey managed to regain the Crimean lands and power, not without military support from Turkey. From this moment it just began overthrow of the Mongol yoke, because the Crimean Khan concluded an alliance with the Moscow prince, and it was a very wise decision.

The Great Stand at Ugra: the end of the Mongol-Tatar yoke and the fall of the Great Horde

As already mentioned, Ivan was a rather advanced politician, he understood perfectly well that the fall of the Mongol-Tatar yoke was inextricably linked with the reunification of Russian lands, and for this allies were needed. Mengli-Girey could calmly help Ahmed Khan establish a new Horde, and return the tribute payments. Therefore, it was extremely important to enlist the support of the Crimea, especially in view of the alliance of the Horde with the Lithuanians and Poles. It was Mengli-Girey who struck the troops of Casimir, preventing them from helping the Horde, but it would be better if we keep the chronology of the events that took place then.

On a quiet and hot May day in 1480, Akhmet raised his army and set out on a campaign against Russia, the Russians began to occupy positions at the Oka River. Moreover, the Horde moved up the Don, destroying quite large territories along the road that were located between Serpukhov and Kaluga. The son of Ivan the Third led his army to meet the Horde, and the tsar himself went to Kolomna with a rather large detachment. At the same time, the Livonian Order was besieging Pskov.

Akhmad reached the Lithuanian lands on the southern side of the Ugra River and stopped, expecting that Casimir's allied unit would join his troops. They had to wait a long time, because just then they had to repel the furious attacks of Mengli-Giray in Podillya. That is, they were absolutely not up to some kind of Akhmat, who with all the fibers of his soul wanted only one thing - the renewal of the former glory and wealth of his own people, or maybe the state. After some time, the main forces of both armies stood on different banks of the Ugra, waiting for someone to attack first.

It didn't take long for the Horde to starve, and the lack of food supplies played a key role in the battle. So, to the question of who defeated the Mongol-Tatar yoke, there is one more answer - hunger, and it is completely correct, though somewhat indirect, and nevertheless. At the same time, Ivan III decided to make concessions to his own brothers, and those with their squads also pulled themselves up to the Ugra. They stood for quite a long time, so much so that the river was completely covered with ice. Akhmat was unwell, he was in complete confusion, and for the fullness of happiness, not at all good news came at all - a conspiracy was planned in Sarai and a ferment of minds began among the people. In late autumn, in November of the same year, poor fellow Akhmat decided to declare a retreat. Out of impotent anger, he burned and plundered everything that came his way, and soon after the New Year he was killed by another enemy - Ibak, the Khan of Tyumen.

After Russia freed itself from the Horde yoke, payments of tribute for vassal dependence were nevertheless renewed by Ivan. He was very busy with the war with Lithuania and Poland in order to argue, therefore he easily recognized the right of Ahmed, the son of Akhmat. For two years, 1501 and 1502, the tribute was regularly collected and delivered to the treasury of the Horde, which supported its life. The fall of the Golden Horde led to the fact that the Russian possessions began to border on the Crimean Khanate, because of which real disagreements began between the rulers, but this is not a story at all of the fall of the Mongol-Tatar yoke.

In Russian sources, the phrase "Tatar yoke" first appears in the 1660s in the insert (interpolation) in one of the copies of the Legend of the Mamayev Massacre. The form "Mongol-Tatar yoke", as the more correct one, was first used in 1817 by Christian Kruse, whose book was translated into Russian in the middle of the 19th century and published in St. Petersburg.

The Tatar tribe, according to the Secret Legend, was one of the most powerful enemies of Genghis Khan. After the victory over the Tatars, Genghis Khan ordered the destruction of the entire Tatar tribe. An exception was made only for young children. Nevertheless, the name of the tribe, being widely known outside Mongolia, also passed on to the Mongols themselves.

Geography and content The Mongol-Tatar yoke, the Horde yoke are a system of political and tributary dependence of the Russian principalities on the Mongol-Tatar khans (until the beginning of the 60s of the 13th century, the Mongol khans, after the khans of the Golden Horde) in the 13th-15th centuries. The establishment of the yoke became possible as a result of the Mongol invasion of Russia in 1237-1242; the yoke was established for two decades after the invasion, including in undisturbed lands. In North-Eastern Russia it lasted until 1480. In other Russian lands, it was eliminated in the XIV century as they were joined to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Poland.

Standing on the Ugra river

Etymology

The term "yoke", meaning the power of the Golden Horde over Russia, is not found in Russian chronicles. It appeared at the turn of the 15th-16th centuries in Polish historical literature. It was first used by the chronicler Jan Dlugosz ("iugum barbarum", "iugum servitutis") in 1479 and the professor at the University of Krakow Matvey Mekhovsky in 1517. In 1575, the term "jugo Tartarico" was used in Daniel Prinz's record of his diplomatic mission to Moscow.

The Russian lands have retained the local princely rule. In 1243, the Grand Duke of Vladimir Yaroslav Vsevolodovich was summoned to the Horde to Batu, recognized as "old by all the prince in the Russian language" and approved in the Vladimir and, apparently, the Kiev princes (at the end of 1245, the governor of Yaroslav Dmitry Eikovich is mentioned in Kiev), although the visits to Batu by two other of the three most influential Russian princes - Mikhail Vsevolodovich, who owned Kiev by that time, and his patron (after the Mongols ruined the Chernigov principality in 1239) Daniel Galitsky - refer to a later time. This act was a recognition of political dependence on the Golden Horde. The establishment of tributary dependence occurred later.

Yaroslav's son Konstantin went to Karakorum to confirm the authority of his father as the Great Khan, after his return Yaroslav himself went there. This example of the khan's sanction to expand the possessions of a loyal prince was not the only one. Moreover, this expansion could take place not only at the expense of the possessions of another prince, but also at the expense of territories that were not ravaged during the invasion (in the second half of the 50s of the XIII century, Alexander Nevsky established his influence in Novgorod, threatening him with the Horde ruin). On the other hand, in order to persuade the princes to loyalty, they could be presented with unacceptable territorial claims, like Daniil Galitsky as the “Mighty Khan” of the Russian chronicles (Plano Carpini calls “Mauzi” among the four key figures in the Horde, localizing his nomad camps on the left bank of the Dnieper): “Give Galich ". And in order to completely preserve his patrimony, Daniel went to Batu and "called himself a slave."

The territorial differentiation of the influence of the Galician and Vladimir Grand Dukes, as well as the Sarai khans and Temnik Nogai during the period of the existence of a separate ulus, can be judged by the following data. Kiev, unlike the lands of the Galicia-Volyn principality, was not liberated by Daniil Galitsky from the Horde Baskaks in the first half of the 1250s, and continued to be controlled by them and, possibly, by the governors of Vladimir (the Horde administration retained its positions in Kiev after the introduction of the Kiev nobility oath to Gediminas in 1324). The Ipatiev Chronicle under 1276 reports that the Smolensk and Bryansk princes were sent to help Lev Danilovich Galitsky by the Sarai khan, and the Turov-Pinsk princes went with the Galicians as allies. Also, the Bryansk prince participated in the defense of Kiev from the troops of Gediminas. The Semeye bordering on the steppe (see the presence of Baskak Nogai in Kursk in the early 80s of the 13th century), located south of the Bryansk principality, apparently shared the fate of the Pereyaslavl principality, which immediately after the invasion came under the direct control of the Horde (in this case, the Danube ulus "Nogai, the eastern borders of which reached the Don), and in the XIV century Putivl and Pereyaslavl-Yuzhny became Kiev" suburbs ".

The khans issued labels to the princes, which were signs of the khan's support for the prince's occupation of this or that table. Labels were issued and were of decisive importance in the distribution of princely tables in North-Eastern Russia (but even there, during the second third of the XIV century, it almost completely disappeared, as did the regular trips of the north-eastern Russian princes to the Horde and their murders there). The rulers of the Horde in Russia were called "kings" - the highest title that was previously applied only to the emperors of Byzantium and the Holy Roman Empire. Another important element of the yoke was the tributary dependence of the Russian principalities. There is information about the population census in the Kiev and Chernigov lands no later than 1246. "They want to" was also sounded during the visit of Daniil Galitsky to Batu. In the early 50s of the XIII century, the presence of the Baskaks in the cities of Poniz'ya, Volhynia and Kiev oblast and their expulsion by the Galician troops was noted. Tatishchev, Vasily Nikitich in his "History of Russia" mentions as the reason for the Horde campaign against Andrei Yaroslavich in 1252 that he did not pay in full for the exit and the tamga. As a result of the successful campaign of Nevryuya, the Vladimir reign was occupied by Alexander Nevsky, with whose assistance in 1257 (in the Novgorod land - in 1259) the Mongolian "census" under the leadership of Kitat, a relative of the Great Khan, conducted a census, after which the regular exploitation of the lands of Vladimir the Great began. reign by collecting tribute. In the late 50s - early 60s of the XIII century, Muslim merchants - "besermen" collected tribute from the northeastern Russian principalities, who bought this right from the great Mongol khan. Most of the tribute went to Mongolia, the great khan. As a result of popular uprisings in 1262 in the northeastern Russian cities, the "besermens" were expelled, which coincided with the final separation of the Golden Horde from the Mongol Empire. In 1266, the head of the Golden Horde was first named a khan. And if most researchers consider Russia conquered by the Mongols during the invasion, then Russian principalities, as a rule, are no longer considered as components of the Golden Horde. Such a detail of Daniil Galitsky's visit to Batu, as “kneeling” (see homage), as well as the obligation of Russian princes, by order of the khan, to send soldiers to participate in campaigns and in round-up hunts (“catches”), underlies the classification of Russian dependence principalities from the Golden Horde as a vassal. There was no permanent Mongol-Tatar army on the territory of the Russian principalities.

The units of taxation were: in the cities - the yard, in the countryside - the economy ("village", "plow", "plow"). In the XIII century, the size of the output was half a hryvnia from the plow. Only the clergy were exempted from tribute, which the conquerors tried to use to strengthen their power. 14 types of "Horde burdens" are known, of which the main ones were: "exit" or "tsar's tribute", a tax directly for the Mongol khan; trade fees ("myt", "tamga"); transportation duties ("yam", "carts"); the maintenance of the khan's ambassadors ("feed"); various "gifts" and "honors" to the khan, his relatives and confidants, etc. Large "requests" for military and other needs were periodically collected.

After the overthrow of the Mongol-Tatar yoke on the territory of all of Russia, payments from Russia and the Commonwealth to the Crimean Khanate were preserved until 1685, in the Russian documentation "Wake" (mother, tysh). They were canceled only by Peter I according to the Treaty of Constantinople (1700) with the wording:

... And before the State of Moscow is an autocratic and free State, there is a dacha, which has been given to the Crimean Khan and Crimean Tatars, either past or now, henceforth may not be obliged from His sacred Imperial Majesty of Moscow, nor from his heirs: but and the Crimean Khans and Crimeans and other Tatar peoples will henceforth neither give a petition, nor any other reason, or cover what is contrary to the world, but let them maintain peace.

Unlike Russia, the Mongol-Tatar feudal lords in the Western Russian lands did not have to change their faith and could possess land with the peasants. In 1840, Emperor Nicholas I, by his decree, confirmed the right of Muslims to own Christian serfs in that part of his empire that was annexed as a result of the divisions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Igo in South Russia

Since 1258 (according to the Ipatiev Chronicle - 1260), the practice of joint Galician-Horde campaigns against Lithuania, Poland and Hungary began, including those initiated by the Golden Horde and Temnik Nogai (during the existence of a separate ulus). In 1259 (according to the Ipatiev Chronicle - 1261), the Mongolian commander Burundai forced the Romanovichs to tear down the fortifications of several Volyn cities.

The campaign of the Galician-Volyn princes, the troops of Mengu-Timur, as well as the Smolensk and Bryansk princes dependent on him, to Lithuania (at the request of Lev Danilovich Galitsky) dates back to the winter of 1274/1275. Novgorodok was taken by Leo and the Horde even before the Allies approached, so the plan for a campaign deep into Lithuania was upset. In 1277, the Galician-Volyn princes, together with Nogai's troops, invaded Lithuania (at the suggestion of Nogai). The Horde ravaged the outskirts of Novgorodok, and the Russian troops did not manage to take Volkovysk. In the winter of 1280/1281, the Galician troops, together with the troops of Nogai (at the request of Lev), besieged Sandomierz, but suffered a partial defeat. Almost immediately followed by a retaliatory Polish campaign and the capture of the Galician city of Perevoresk. In 1282, Nogai and Tula-Buga ordered the Galician-Volyn princes to go with them to the Hungarians. The troops of the Volga horde got lost in the Carpathians and suffered serious losses from hunger. Taking advantage of the absence of Leo, the Poles again invaded Galicia. In 1283, Tula-Buga ordered the Galician-Volyn princes to go with him to Poland, while the environs of the capital of the Volyn land were seriously damaged by the Horde army. Tula-Buga went to Sandomierz, wanted to go to Krakow, but he had already gone there through Przemysl Nogai. The Tula-Buga troops were stationed in the vicinity of Lviv, which were seriously affected as a result of this. In 1287, Tula-Buga, together with Alguy and the Galician-Volyn princes, invaded Poland.

The principality paid an annual tribute to the Horde, but information about the census available for other regions of Russia is not available for the Galicia-Volyn principality. There was no Basque institute in it. The princes were obliged to periodically send their troops to participate in joint campaigns with the Mongols. The Galicia-Volyn principality pursued an independent foreign policy, and not one of the princes (kings) after Daniel Galitsky traveled to the Golden Horde.

The Galicia-Volyn principality did not control Ponizye in the second half of the 13th century, but then, taking advantage of the fall of the Nogai ulus, regained control over these lands, gaining access to the Black Sea. After the death of the last two princes from the male line of the Romanovichs, which one of the versions associates with the defeat from the Golden Horde in 1323, they again lost them.

Polesie was annexed by Lithuania at the beginning of the XIV century, Volyn (finally) - as a result of the War for the Galician-Volyn inheritance. Galicia was annexed by Poland in 1349.

The history of the Kiev land in the first century after the invasion is very poorly known. As in North-Eastern Russia, the institution of the Baskaks existed there and raids took place, the most destructive of which was noted at the turn of the XIII-XIV centuries. Fleeing from Mongol violence, the Kiev Metropolitan moved to Vladimir. In the 1320s, the Kiev land fell into dependence on the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, but the Khan's Baskaks continued to stay in it. As a result of Olgerd's victory over the Horde at the Battle of Blue Waters in 1362, the Horde's rule in the region was ended. The Chernihiv land has undergone strong crushing. For a short time, the Bryansk principality became its center, but at the end of the XIII century, presumably with the intervention of the Horde, it lost its independence, becoming the possession of the Smolensk princes. The final approval of Lithuanian sovereignty over the Smolensk and Bryansk lands took place in the second half of the 14th century, however, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 70s of the 14th century resumed the payment of tribute from the southern Russian lands within the framework of an alliance with the West Volga Horde.

Igo in North-Eastern Russia

Boris Chorikov "The discord of the Russian princes in the Golden Horde for the label to the great reign"

After the overthrow of the Horde army in 1252 from the Vladimir grand-ducal throne of Andrei Yaroslavich, who refused to serve Batu, in Ryazan, Prince Oleg Ingvarevich Krasny was released from his 14-year captivity, apparently under the condition of complete submission to the Mongol authorities and assistance to their policy. Under him, the Horde census took place in the Ryazan principality in 1257.

In 1274, the Khan of the Golden Horde Mengu-Timur sent troops to help Lev Galitsky against Lithuania. The Horde army passed westward through the Smolensk principality, with which historians associate the spread of the Horde's power to it. In 1275, simultaneously with the second census in North-Eastern Russia, the first census was carried out in the Smolensk principality.

After the death of Alexander Nevsky and the division of the core of the principality, a fierce struggle for the great Vladimir reign was going on between his sons in Russia, including that kindled by the Sarai khans and Nogai. Only in the 70-90s of the XIII century they organized 14 campaigns. Some of them were in the nature of the devastation of the southeastern outskirts (Mordovians, Murom, Ryazan), some were carried out in support of the Vladimir princes in the Novgorod "suburbs", but the most destructive campaigns were the campaigns, the purpose of which was to forcefully replace the princes on the grand prince's throne. Dmitry Alexandrovich was initially overthrown as a result of two campaigns by the troops of the Volga Horde, then Vladimir returned with the help of Nogai and was even able to inflict the first defeat on the Horde in the northeast in 1285, but in 1293 he first, and in 1300 Nogai himself was overthrown Tokhtoy (the principality of Kiev was ruined, Nogai fell at the hands of a Russian soldier), who had occupied the Sarai throne before that with the help of Nogai. In 1277, the Russian princes took part in the Horde campaign against the Alans in the North Caucasus.

Immediately after the unification of the western and eastern uluses, the Horde returned to the all-Russian scale of its policy. In the very first years of the XIV century, the Moscow principality expanded its territory many times at the expense of neighboring principalities, claimed Novgorod and was supported by Metropolitan Peter and the Horde. Despite this, the label was mainly owned by the princes of Tver (in the period from 1304 to 1327 for a total of 20 years). During this period, they were able to forcefully establish their governors in Novgorod, defeat the Tatars in the Battle of Bortenev, kill the Moscow prince at the headquarters of the khan. But the policy of the Tver princes collapsed when Tver was defeated by the Horde in alliance with the Muscovites and Suzdal in 1328. At the same time, this was the last power change of the Grand Duke by the Horde. Received in 1332 the label Ivan I Kalita - the prince of Moscow, which strengthened against the background of Tver and the Horde, - won the right to collect an "exit" from all the northeastern Russian principalities and Novgorod (in the XIV century, the size of the exit was equal to a ruble from two soils. "Moscow exit "Was 5-7 thousand rubles in silver," Novgorod exit "- 1.5 thousand rubles). At the same time, the Basque era ended, which is usually explained by repeated "veche" performances in Russian cities (in Rostov - 1289 and 1320, in Tver - 1293 and 1327).

The chronicler's testimony "and there was a great silence for 40 years" (from the defeat of Tver in 1328 to the first campaign of Olgerd against Moscow in 1368) was widely known. Indeed, the Horde troops did not act during this period against the holders of the label, but repeatedly invaded the territory of other Russian principalities: in 1333, together with the Muscovites, into the Novgorod land, which refused to pay tribute in an increased amount, in 1334, together with Dmitry Bryansk, against Ivan Alexandrovich Smolensky, in 1340, led by Tovlubiy - again against Ivan Smolensky, who entered into an alliance with Gedimin and refused to pay tribute to the Horde, in 1342 with Yaroslav-Dmitry Alexandrovich Pronsky against Ivan Ivanovich Korotopol.

From the middle of the XIV century, the orders of the khans of the Golden Horde, not backed up by real military force, were no longer carried out by the Russian princes, since the "great zamyatnaya" began in the Horde - a frequent change of khans who fought with each other for power and ruled simultaneously in different parts of the Horde. Its western part was under the control of the temnik Mamai, who ruled on behalf of the puppet khans. It was he who claimed supremacy over Russia. Under these conditions, the Moscow prince Dmitry Ivanovich Donskoy (1359-1389) did not obey the khan's labels issued to his rivals, and seized the Grand Duchy of Vladimir by force. In 1378 he defeated the punitive Horde army on the river. Vozhe (in Ryazan land), and in 1380 won a victory in the Battle of Kulikovo over the army of Mamai. Although after the accession to the Horde of the rival Mamai and the legitimate khan - Tokhtamysh, Moscow was devastated by the Horde in 1382, Dmitry Donskoy was forced to agree to an increased tribute (1384) and leave his eldest son Vasily in the Horde as a hostage, he retained the great reign and for the first time was able to transfer to his son without the khan's label, as "his fatherland" (1389). After Tokhtamysh's defeat from Timur in 1391-1396, the payment of tribute stopped until the invasion of Edigei (1408), but he failed to take Moscow (in particular, the Tver prince Ivan Mikhailovich did not fulfill Edigei's order "to be on Moscow" with artillery).

In the middle of the 15th century, the Mongol troops conducted several devastating military campaigns (1439, 1445, 1448, 1450, 1451, 1455, 1459), achieved private successes (after the defeat in 1445, Vasily the Dark was captured by the Mongols, paid a large ransom and gave some Russian cities to feed them, which became one of the points of accusation of other princes who captured and blinded Vasily), but they could no longer restore their power over the Russian lands. The Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan III in 1476 refused to pay tribute to the khan. After the unsuccessful campaign of the Khan of the Great Horde Akhmat and the so-called "Standing on the Ugra" in 1480, the Mongol-Tatar yoke was completely eliminated. The acquisition of political independence from the Horde, along with the spread of Moscow's influence over the Kazan Khanate (1487), played a role in the subsequent transfer of part of the lands that were under the rule of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to Moscow's rule.

In 1502, for diplomatic reasons, Ivan III recognized himself as a slave of the Khan of the Great Horde, but in the same year the troops of the Great Horde were defeated by the Crimean Khanate. Only under the treaty of 1518 were the positions of the darug of the Moscow prince of the Great Horde finally abolished, which at that time virtually ceased to exist.

And darags and duties Darazhsky other duties in no way exist ....

Military victories over the Mongol-Tatars

During the Mongol invasion of Russia in 1238, the Mongols did not reach 200 km to Novgorod and passed 30 km east of Smolensk. Of the cities that were on the way of the Mongols, only Kremenets and Holm were not taken in the winter of 1240/1241.

The first field victory of Russia over the Mongols took place during the first campaign of Kuremsy to Volhynia (1254, according to the GVL dating in 1255), when he unsuccessfully besieged Kremenets. The Mongol vanguard approached Vladimir Volynsky, but after the battle at the city walls retreated. During the siege of Kremenets, the Mongols refused to help Prince Izyaslav to take possession of Galich, he did it on his own, but was soon defeated by an army led by Roman Danilovich, upon the dispatch of which Daniel said "if there are Tatars themselves, let your heart not be horrified." During the second campaign of Kuremsy to Volhynia, which ended in an unsuccessful siege of Lutsk (1255, according to the GVL dating in 1259), a squad of Vasilko Volynsky was sent against the Tatar-Mongols with the order to "beat the Tatars and take them prisoner." For a virtually lost military campaign against Prince Danila Romanovich, Kurems was removed from command of the army and replaced by Temnik Burunday, who forced Danil to destroy the border fortresses. Nevertheless, the power of the Horde over Galicia and Volyn Rus' Burundi failed to restore, and after that none of the Galicia-Volyn princes went to the Horde for labels to reign.

In 1285, the Horde, led by Tsarevich Eltorai, ravaged the Mordovian lands, Murom, Ryazan and went to the Vladimir principality together with the army of Andrei Alexandrovich, who claimed the grand ducal throne. Dmitry Alexandrovich gathered an army and marched against them. Further, the chronicle reports that Dmitry captured part of the boyars Andrei, "drove the Tsarevich out."

“In the historical literature, the opinion has been established that the Russians won the first victory in a field battle over the Horde only in 1378 on the Vozha River. In reality, the victory "in the field" was wrested by the regiments of the senior "Alexandrovich" - Grand Duke Dmitry - almost a hundred years earlier. Sometimes traditional assessments turn out to be surprisingly tenacious for us "

In 1301, the first Moscow prince Daniil Alexandrovich defeated the Horde at Pereyaslavl-Ryazan. The consequence of this campaign was the capture by Daniel of the Ryazan prince Konstantin Romanovich, who was later killed in a Moscow prison by Daniel's son Yuri, and the annexation of Kolomna to the Moscow principality, which marked the beginning of its territorial growth.

In 1317, Yuri Danilovich of Moscow, together with the army of Kavgadyya, came from the Horde, but was defeated by Mikhail Tverskoy, the wife of Yuri Konchak (sister of the Khan of the Golden Horde Uzbek) was captured and subsequently perished, and Mikhail was killed in the Horde.

In 1362, a battle took place between the Russian-Lithuanian army of Olgerd and the united army of the khans of the Perekop, Crimean and Yambaluk hordes. It ended with the victory of the Russian-Lithuanian forces. As a result, Podillia was liberated, and later the Kiev region.

In 1365 and 1367, respectively, took place at the Shishevsky forest, won by the Ryazan people, and the Battle of Pian won by the Suzdal people.

The Battle of the Vozha took place on August 11, 1378. Mamai's army under the command of Murza Begich was sent to Moscow, was met by Dmitry Ivanovich on Ryazan land and defeated.

The Battle of Kulikovo in 1380 took place, like the previous ones, during the period of the “great hush” in the Horde. Russian troops led by Prince of Vladimir and Moscow, Dmitry Ivanovich Donskoy, defeated the troops of the temnik beklyarbek Mamai, which led to a new consolidation of the Horde under the rule of Tokhtamysh and the restoration of dependence on the Horde of the lands of the great reign of Vladimir. In 1848, a monument was erected on Red Hill, where Mamai's headquarters was located.

And only 100 years later, after the unsuccessful raid of the last khan of the Great Horde, Akhmat, and the so-called "Standing on the Ugra" in 1480, the Moscow prince managed to withdraw from the subordination of the Great Horde, remaining only a tributary of the Crimean Khanate.

The meaning of the yoke in the history of Russia

At present, scientists have no consensus on the role of the yoke in the history of Russia. Most researchers believe that its results for the Russian lands were destruction and decline. Apologists of this point of view emphasize that the yoke threw the Russian principalities back in their development and became the main reason for Russia's lag behind the countries of the West. Soviet historians noted that the yoke was a brake on the growth of the productive forces of Russia, which were at a higher socio-economic level in comparison with the productive forces of the Mongol-Tatars, and for a long time it preserved the natural character of the economy.

These researchers (for example, the Soviet academician B.A.Rybakov) note in Russia during the yoke the decline of stone construction and the disappearance of complex crafts, such as the production of glass decorations, cloisonné enamel, niello, grain, and polychrome glazed ceramics. “Russia was thrown back several centuries, and in those centuries when the guild industry of the West was passing to the era of initial accumulation, the Russian handicraft industry had to pass a second part of the historical path that had been done to Batu” (Rybakov B. A. “Craft Ancient Rus ", 1948, p. 525-533; 780-781).

Dr. East. Sciences BV Sapunov noted: “The Tatars destroyed about a third of the entire population of Ancient Rus. Considering that at that time about 6-8 million people lived in Russia, at least two - two and a half were killed. Foreigners passing through the southern regions of the country wrote that practically Russia was turned into a dead desert, and there is no longer such a state on the map of Europe ”.

Other researchers, in particular, the outstanding Russian historian Academician N.M. Karamzin, believe that the Tatar-Mongol yoke played a crucial role in the evolution of Russian statehood. In addition, he also pointed to the Horde as the obvious reason for the rise of the Moscow principality. Following him, another prominent Russian historian, academician, professor at Moscow State University V.O. Klyuchevsky also believed that the Horde had prevented exhausting, fratricidal internecine wars in Russia. "The Mongol yoke in extreme poverty for the Russian people was a harsh school in which Moscow statehood and Russian autocracy were forged: a school in which the Russian nation realized itself as such and acquired character traits that made it easier for its subsequent struggle for existence." Supporters of the ideology of Eurasianism (G.V. Vernadsky, P.N.Savitsky and others), without denying the extreme cruelty of Mongol rule, rethought its consequences in a positive way. They highly appreciated the religious tolerance of the Mongols, opposing it to the Catholic aggression of the West. They viewed the Mongol Empire as the geopolitical predecessor of the Russian Empire.

Later, similar views, only in a more radical version, were developed by L.N. Gumilev. In his opinion, the decline of Russia began earlier and was associated with internal reasons, and the interaction of the Horde and Russia was a beneficial military-political alliance, primarily for Russia. He believed that the relationship between Russia and the Horde should be called "symbiosis". What a yoke, when "Great Russia ... voluntarily united with the Horde thanks to the efforts of Alexander Nevsky, who became Batu's adopted son." What yoke can there be if, according to L. N. Gumilyov, on the basis of this voluntary association an ethnic symbiosis of Russia with the peoples of the Great Steppe arose - from the Volga to the Pacific Ocean and from this symbiosis the Great Russian ethnos was born: “a mixture of Slavs, - Finns, Alans and Turks have merged into the Great Russian nationality? LN Gumilyov called the uncertainty that reigned in Soviet domestic history about the existence of the "Tatar-Mongol yoke" a "black legend." Before the arrival of the Mongols, numerous Russian principalities of Varangian origin, located in the basins of rivers flowing into the Baltic and Black Seas, and only in theory recognized the power of the Kiev Grand Duke over themselves, in fact did not constitute one state, and the name of a single Russian is inapplicable to the tribes of Slavic origin that inhabited them. people. Under the influence of Mongol rule, these principalities and tribes were merged into one, forming first the Muscovy and later the Russian Empire. The organization of Russia, which was the result of the Mongol yoke, was undertaken by the Asiatic conquerors, of course, not for the good of the Russian people and not for the sake of the exaltation of the Moscow Grand Duchy, but because of their own interests, namely for the convenience of ruling the conquered vast country. They could not allow in it an abundance of small rulers living at the expense of the people and the chaos of their endless strife, undermining the economic well-being of their subjects and depriving the country of the security of communications, and therefore, naturally, encouraged the formation of a strong power of the Moscow Grand Duke, which could keep in subjection and gradually absorb the specific principalities. This principle of creating autocracy, in all fairness, seemed to them for this case more appropriate than the well-known and well-tested Chinese rule: "divide and rule." Thus, the Mongols began to collect, to organize Russia, like their state, for the sake of establishing order, legality and prosperity in the country.

In 2013, it became known that the yoke would be included in a single textbook on the history of Russia in Russia called the “Horde yoke”.