Dobrotvorskaya has anyone seen the girl read. Book of September: memoirs of Karina Dobrotvorskaya

Read also

Dobrotvorskaya K. Has anyone seen my girl?

100 letters to Seryozha. M.: AST, 2014.

On the dust jacket of Karina Dobrotvorskaya’s book “Has Anyone Seen My Girl? 100 letters to Seryozha" is the epigraph:

You lost your girl.

You didn't make your own movie.

You always sat in the front row.

There was no boundary between you and the screen.

You stepped behind the screen -

How Jean Cocteau's Orpheus stepped into the mirror

Well, that's all.

Karina Dobrotvorskaya made a movie. She made a movie that Sergei Dobrotvorsky, her husband, did not make. She once left him, and he died. Then everyone said “he died of love” without surviving Karina’s departure. The legend of a romantic death lived in the “viewer’s” consciousness for many years, and now it is partly being destroyed: Dobrotvorsky died of an overdose, like many in the 90s, and Sergei’s admirers also cannot forgive the book for this detail... Many do not want to know much at all .

In “100 Letters” one constantly hears the regret that the wonderful film critic and screenwriter Seryozha Dobrotvorsky did not make a real, big, professional movie. Karina thinks a lot about this fact; it always seemed to her like some kind of cowardice, creative cowardice, lack of embodiment, or something. Now she filmed it herself, filmed it on paper: with episodes, their storyboards, role lines, characters, scenery, interior details in different apartments, cities and countries. The movie is black and white, like photographs in a book.

And the heroine of this film is her.

Everyone quarreled because of this book. Well, firstly, because of the “moral and moral”: does Karina have the right to turn to Seryozha, whom - with all his talents - she abandoned for the sake of the Moscow creamy life, a bourgeois family? And secondly and most importantly (hence the “moral and ethical” aspect) - because the tragic departure of a significant person gives rise to a “widow effect”: memory tends to be privatized and monopolized by many who were nearby in one way or another, helped, especially in difficult moment, had some spiritual contacts and, therefore, can consider himself an executor. Memory is monopolized most often by women—devout friends (including abandoned husbands). So after the book was published, the Internet space was filled with everything: “I won’t even open it, I’m afraid, I knew Dobsky too well.” - “Opened it. Crazy exhibitionism. Closed." — “The queen of glamor about her suffering? From Paris with love?" - “Where is her ethical right, he died without her!”

Not very calmly (“I don’t understand this kind of undressing...”), but with extreme interest I read, as I know, the book “Dear Mokhovaya” - Seryozha and Karina’s alma mater, the Theater Academy, a close environment, but not affected by the relations of the film crowd of the 90s. “Dear Mokhovaya” in its female incarnation perceived the book as very close to almost everyone who graduated from theater studies. I spoke to many. Almost every reader had an identification effect, if this reader is a theater expert... “Moss Wednesday” is inclined to analyze a dramatic text, which is more important than life, and Karina writes precisely a script, a psychological drama that gives the opportunity for reflection, identification, and interpretation.

In the finale I will also end with some kind of interpretation.

Once upon a time, we were sitting in the editorial basement with a former student, then our editor, and thinking about how we could earn money to publish a magazine. “It is necessary that each of the members of our women’s editorial board, a theater expert by training, write their own story, a women’s novel - and there will be a series “Russian Woman”, which will financially save “PTZh”,” she said, and I agreed.

Now she writes scripts for TV series, I write a book review, and Karina Dobrotvorskaya writes that same women’s story.

We have never been close - neither with Seryozha Dobrotvorsky, nor with Karina Zaks. But there is one bright picture in my memory.

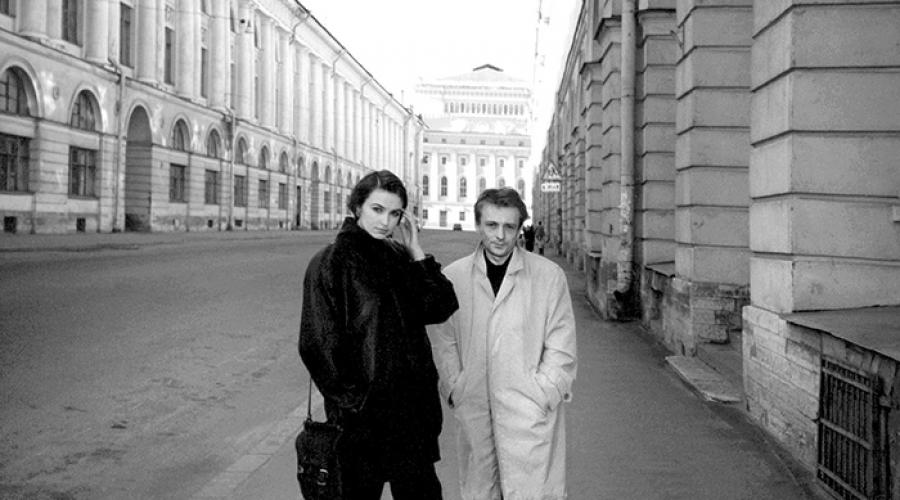

...June, thesis defenses, packed with people, sunny and stuffy auditorium 418, windows open. Karina’s course is defended, including Lenya Popov (I’m his leader) - and in the midst of defenses, the excited Karina (she’s about to defend herself) and Seryozha enter, make their way between people, carrying papers, bags, reviews, the text of the diploma, an answer to the opponent. They crawl to the window and sit on the windowsill. For some reason I remember the backdrop of the sun in Karina’s long hair at that time - and from her plasticity, from her excitement, I understand: she and Seryozha are together. At that moment this was news to me.

The picture has been in my memory for 25 years as a still from some movie. Maybe some of our common films of those years, although we followed different paths.

I call the author of the book Karina, without a last name, because we know each other. Faculty orchid, a gentle beauty with a quiet voice, gravitating towards aestheticism. Her first article in our magazine was called “Lioness” and was about Ida Rubinstein. Karina also wrote to PTZ later, although only a little: she went to Moscow to see her new husband Alexei Tarkhanov. In Moscow, she really became a “lioness” - in the sense that she worked and works in rich glamor magazines, the names of which have nothing to do with the “raznochinny” readers of “PTZ”, scattered throughout the Russian regions... Now, for example, she is the president and Editorial Director of Brand Development for Conde Nast International. The Internet reports that “this position at Conde Nast International, which publishes Vogue, Glamour, Vanity Fair, GQ, AD, Tatler, Allure, Conde Nast Traveler and other legendary magazines around the world, was introduced for the first time and specifically for Karina Dobrotvorskaya. She is responsible for the launch and development of new print and digital products for the international publishing house, which has a portfolio of more than 120 magazines and 80 websites in 26 markets.”

For several days in a row, I walked home with the constant Mokhova, along the same fateful crossing through Belinsky, where Karina first saw Seryozha (this is described in detail in the book), and anticipated the pleasure: now I’ll finish my work and go to bed to read. I recorded this expectation, I was waiting for the meeting with the book. Three hundred pages that can be read in one fell swoop (the book is fascinating, dynamic, addictive, immersive...), I read it for a week in series mode (what awaits me there in the next episode?). Gradually, in small parts, slowly moving from scene to scene. In a word, I watched a serial movie (especially since I know almost all the characters, from Lyuba Arkus to Misha Brashinsky, and the chronotope of the book is also my time/space).

For several years in a row, the Dobrotvorsky family of critics played two or three films a day on video, and in the evening they went to the House of Cinema. Karina compares almost every episode of her real life in one way or another with scenes of a film. “As if I were the heroine of Rosemary’s Baby” (p. 313), “As if at any moment I could find myself in a scene from Invasion of the Body Snatchers” (p. 290), however, you don’t have to specify the pages, it’s almost on each: for the Dobrotvorskys, the second reality did not arise episodically, it was not even a context, it, accompanying life constantly, was the text itself; they communicated, often quotationally, through cinema. It seems that even now Karina watches a film a day, so the aestheticization of reality and dual worlds are inevitable. This cinematic quality aestheticizes his and Seryozha’s story, referring each episode to the figurative series of great films that seem to depict the time and life of the 90s. Well, the Dobrotvorskys are made into movie heroes. No wonder Karina always compares Seryozha to David Bowie.

And so, in fact, for everyone who is related to the second reality, to art. We always feel like characters in a film (optionally, a play). Theater people talk in quotes from Chekhov (I once even thought that we live our lives illustrating a story that has already been written: today you are Irina, then Masha, and at the same time Arkadina). We live quotationally, we walk down the street, seeing ourselves from the outside, as if in a frame, and at the same time framing the surrounding reality and watching it like a movie: oh, this should have been filmed, that’s the angle, that’s the light coming in... “Someday about our stories will be made into movies. It’s a pity that Gabin has already died, he would have played me,” a person once told me who hardly knows Bowie and to whom a book from the “Breathless” series by AST publishing house could also be dedicated, but I don’t have Karina’s courage Dobrotvorskaya, and the man is alive. Honestly, the infectiousness of “100 Letters to Seryozha” is such that I even decided to write “with my last breath” and put on the table a documentary novel called “You Will Never Die” - so that later no one would have complaints like with Dobrotvorskaya: Seryozha won’t answer, you can write your own version...

This is not the first book by Karina Dobrotvorskaya. There were also “Siege Girls”: recordings of memories of those who survived the siege as children (the plot of the action is the “siege complex” of every Leningrad child, genetic memory for hunger, phantom pains and fears). In these memories there is a lot that is the same, a lot that is different, but the real development of the action is the diary of Karina herself about how she entered into the topic of the siege and read literature from the siege. In short, as taught in the theater history seminar, Karina studies the sources and shares her thoughts about them in this diary of hers. But she thinks about the blockade (and doesn’t hide it) in expensive restaurants, while eating dishes whose names I don’t remember, and they won’t say anything to our reader, scattered across the regions... She reads blockade books on the terrace of her house in Montenegro, in Paris and New York, while torturing herself with diets to remain beautiful. Her characters thought only about food (as if to eat), she thinks about food almost as much (as if not to eat). Devout fasting for weight loss in glamorous latitudes - and the length of the siege hunger create the lyrical and eccentric texture of the book, its internal plot, and conflict. And the point here is not in understanding her satiety (Karina really has no problem buying an apartment in Paris or on Bolshaya Konyushennaya...) and not in the desire/unwillingness to return to Leningrad, but in a certain Dostoevsky “underground” consciousness of a charming mother of two lovely children and a lucky glamorous journalist. With the talent of a psychologist (why does she need psychologists and psychoanalysts when she understands everything herself?) she explores her own inner landscape and does it with the irony of a prosperous Moscow “lioness” and the insecurity of a little girl living near the Gigant cinema, next to which captured Germans were hanged in front of the crowd.

On the cover of the book are not the besieged girls, but little Karina and her joyful girlfriends of the early 1970s. And this book is about them, about themselves, this is an internal portrait of an intelligent and subtle person, reviewing the theater of his life against the backdrop of the siege scenery, this is a psychoanalysis session, because writing a book is getting rid of the siege phantom... It is very interesting to follow this brave journey.

The last paragraph also applies to the book I’m talking about now. Karina even formulates a “psychotherapeutic” law herself: through text, having fallen in love with a certain “second Seryozha,” she takes out many years of pain over Seryozha Dobrotvorsky. I don’t know if the statement is absolutely sincere that since his death she lived two parallel lives (“After he left, my life fell apart into external and internal. Externally, I had a happy marriage, wonderful children, a huge apartment, a wonderful job, a fantastic career and even a small house on the seashore. Inside there is frozen pain, dried tears and an endless dialogue with a person who was no longer there"), but I know for sure: in order to forget something that plagues you, you have to give it to paper. Is it good that the pain goes away? I don’t know, I’m not sure: having given it to the paper, you feel “mournful insensibility”, but you can’t return it...

In general, Dobrotvorskaya’s book is an internal portrait of a constantly reflective person. This is an explanation of oneself in the neorealistic scenery of the 90s: everyone has already noted the detailed reconstruction of the time with its food poverty and creative drive. Building a conflict, as taught, Karina here also resorts to the principle of contrast. She recalls her story with Seryozha, unfolding in the damp St. Petersburg underground, against the backdrop of a new romance taking place in Paris, in expensive restaurants (the new young lover does not like them, but she is used to it). If with Dobrotvorsky there is love as such (one friend of mine would say “vertical”), then here love is physical, “horizontal”. If the first Seryozha is an intellectual, then the second is a computer scientist, read three books, loves TV series. And so on. Actually, the husband Alexey Tarkhanov appears as a contrast (with Seryozha - love, here - the first orgasm, there - a miserable life, here - the white apartment of a wealthy Moscow journalist, there - the tragic impossibility of having children, here - pregnancy with his son Ivan...).

Actually, we get so used to reading the texts of reality itself, so we catch their artistic meaning and give imagery to any movement, that life itself acquires a plot. Karina has nothing to invent when she describes a trip to Seryozha’s grave - this is an uninvented, but internally constructed film episode. She brings him a small clay ox for his grave. “Just don’t turn the ox around for me!” - they often shouted to each other, quoting “The black rose is the emblem of sadness...”. Seryozha then drew a sad ox, she blinded it and then took it with her to Moscow. Now she has returned and placed it on the grave. Movie? An episode built in real life. All that remains is to remove...

Karina deals with herself, as if not showing off - and at the same time seeing herself “in the frame” and admiring herself, her outfits, her appearance and talent (at the same time she claims that she is wildly complex, and this is also true). It’s as if she sees the lost “girl” through the eyes of director Dobrotvorsky, who is making a movie about her. She builds the mise-en-scène and, having parted with the new Seryozha, lies on the floor in the same position in which she lay when she learned about Dobrotvorsky’s death. The author, of course, is characterized by extreme egocentrism, but whoever in our environment is not egocentric, is not preoccupied with himself and does not remember himself in the mise-en-scène - let him throw a stone...

Does Karina understand others? Without a doubt. And it gives you a reason to publicly deal with yourself. We're even. She puts an end to “widow privatization,” authoritatively asserting with a book: mine. My history. My Seryozha.

Do those still alive need such frank memoirs? Why not? Does the book have a boulevard flavor? Probably, but that didn't bother me.

Does the book resemble psychological prose? Yes, I think so. At least, many topics resonated with me with understanding and attention, although it is difficult to imagine more different lives than Karina’s and mine... The basement on Mokhovaya and the beggar “PTZh”, guarding the profession that Karina left for the sake of (hereinafter - according to information from the Internet... ), - isn't this the principle of contrast?

Karina Dobrotvorskaya’s prose may be a romance for women, only in the center of it is a completely “Dostoevsky” creature, aware of its “undergroundness” and interesting with this honest undergroundness (but is it only aware of glamor?). It, this female creature, sincerely unravels the labyrinths of its history in a hundred letters to... Ivan.

Yes, yes, Karina and Seryozha called each other Ivans, Ivanchiks and other derivatives. Never by name. Karina named her son Ivan (this is also in terms of the plot of life and Dostoevschina), born from Tarkhanov.

And here I have an interpretative guess. Addressing Ivan, Ivanchik, protected by his undeniable love for her, Karina describes herself and her love, her nature, her destiny, her life - for another addressee, for a new Seryozha. Dobrotvorsky already knew everything. But the second Seryozha (who is actually Sasha Voznesensky, as written in the afterword)... The book of letters to Ivan, as it seems, is addressed in the title to the current lover, these are a hundred letters to the new Seryozha, an explanation with the one who wants to open all the riches the life that has been lived and the result of which is the resulting “cumulative experience” of an intelligent and talented person.

"Has anyone seen my girl?" Yes, that’s the point, I didn’t see it! Didn't see it! Lost! Didn't make it into a movie! I missed the wealth that this girl from Mokhovaya represents! Karina Dobrotvorskaya bravely made this typical emotion public. It’s as if she’s shouting to Seryozha: “You’ve lost!” She didn't lose it - he did. I have lost the one who is now writing this book - a book by no less interesting person, no less significant personality than the late Seryozha Dobrotvorsky.

Marina DMITREVSKAYA

November 2014

" This is the first book in the memoir series “Breathless,” conceived by Elena Shubina. The book will be on sale soon. Critic Nina Agisheva wrote about “The Girl,” its author and main character for “Snob.”

Karina, dear, I remember how my Seryozha sent me your text by email with the words: “Look, you might be interested.” I was in no hurry to watch: I don’t like women’s prose and call it “snot with ice cream.” After all, Marina, whom we both adored, was not a woman - she was a genius. And the most interesting - and the most creative - people are those in whom both principles are intricately mixed. But in the evening I sat down at the computer and... woke up in the middle of the night. I haven’t read anything like the power of emotional expression, desperate fearlessness and unvulgar frankness for many years. And in general, all this was not about you, not even about us - about me.

Although I saw the hero of the book - the legendary St. Petersburg critic and your ex-husband Seryozha Dobrotvorsky - only twice in my life. Once in Moscow at the “Faces of Love” festival, where he received a prize for his articles about cinema, and I, wanting to say something nice to him, said socially: “You have a very pretty wife, Seryozha.” The answer was not entirely secular - he looked at me very angrily and said: “No, you are wrong. She's not pretty, she's beautiful." And the second time, years later, when you had already left him and lived with Lesha Tarkhanov, at Lenfilm, where I whiled away the time in the buffet, waiting for the next interview. Seryozha sat down at my table with a bottle of cognac in his hands - and, although we were not closely acquainted, he just unleashed a stream of revelations on me. Not a word was said about you: he had just returned from either Prague or Warsaw and was describing in many words how brilliantly this trip had been, and how happy, incredibly happy he was, how good everything was in his life... Less than month he died. I remember then I looked at him with pity and thought: how he suffers, poor thing. This is love. Now I understand that his behavior was inappropriate, and I know why.

Just one post on my FB speaks about who Dobrotvorsky was and remains for the St. Petersburg intellectual get-together. A student writes: oh, read everything, a book is coming out about the famous Dobrotvorsky - you know, he died the year we entered LGITMIK. So, Karina, all your experiences, for the sake of which you started this book, have faded into the shadows - what remains is the portrait of Seryozha. And he is beautiful, as is his photograph on the cover of the book of his brilliant articles, lovingly published by Luba Arcus. I like it so much that I put this book on the shelf with the cover facing out - and when you and Lesha first came to me, he was just opposite, and Seryozha looked at him bitterly and ironically all evening. He really looked like James Dean. And David Bowie. And in general, what could be more erotic than intelligence? I completely agree with you.

You knew Seryozha closely, very closely, you remembered many of his assessments and aphorisms, phenomenal in accuracy and elegance, which are scattered in the text like a handful of expensive stones - now they don’t write or speak like that! - and at the same time, you are still tormented by his under-incarnation. Yes, articles, yes, paintings, even in the Russian Museum! Yes, scripts, but who remembers these films?! You write: “How to convey a gift that has not been embodied? Talent to live? Artistry mixed with despair?.. Those whom you burned, irradiated - they remember it. But there won't be any. And you won't be there." Karina, there are many such destinies around... I remember my shock at the early films of Oleg Kovalov, at his talent - where is he now, what is he? And those who wrote like gods - what are they doing now?! When was the last time you wrote about the theater? And where are your studies about Isadora Duncan? So what? The main thing is not to take a breath, as your Seryozha wrote in an article about his beloved Godard. Live. And rejoice at the “new manifestos of freedom, permissiveness and love.”

By the way, about permissiveness. I don’t know many authors who are capable of writing so harshly, ironically and frankly about the morals of bohemian St. Petersburg in the eighties and nineties. As, by the way, women who publicly declare that they do not have a waist and that they do not know how to dress. I never expected such “immensity in the world of measures” from the coldly sleek boss of Condenast. It's like a volcano inside an iceberg. And a simple explanation, as eternal as the world, is love. She either exists or she doesn't. And if it is there, it doesn’t go anywhere. Forever with you, until your last breath - and no book can get rid of it. But this is so, a lyrical digression. Let's get back to drinking. Our generation not only paid tribute to him, but also aestheticized it as best it could. It is no coincidence that Dobrotvorsky said about the unforgettable Venichka Erofeev that he “preserved the tradition of conscience in a clot of hangover shame.” Or was this how weakness of will was justified? You write with such pain about those moments when “Mr. Hyde” woke up in Seryozha that it’s impossible not to believe you. And it’s not for us to judge. We will all die next to those with whom we “have something to drink.” But there is a line beyond which it is better not to look. Feeling it, you left - and survived. I thought about this while watching Guy Germanika’s film “Yes and Yes.” Of course, his heroine is no match for you in terms of intelligence and brilliance, but she also loved and was also saved. I don’t understand at all how the numerous detractors of this picture did not consider or hear the main thing: the story of pure and devoted love. And the surroundings - well, excuse me, what they are. Moreover, Germanika does not try to justify it or embellish it, stylize it as something - no, horror is horror. We must run. And all of us, even those who now criticize the film for nothing, somehow escaped. How can one not remember that morality awakens precisely when... And another theme arises in your book and in “women’s” cinema today (I remember Angelina Nikonova and Olga Dykhovichnaya with their stunning “Portrait at Twilight”, Svetlana Proskurina, Natalya Meshchaninova - the list is easy to continue): it is women who disagree again and again, rebel and run away from “doll” houses, although these houses today look more like “dead”. This, by the way, is exactly what Yana Troyanova plays in Sigarev’s play. In general, only girls will survive. While the boys sit on Facebook and self-destruct.

Your book is generally like a movie in which all the pictures of our common life replace one another. Here are BG and Tsoi. Kuryokhin. Here is a stupid parallel cinema in today's opinion - I didn’t like it either, although I once even supervised a dissertation about it at the journalism department. Here's Lynch's Blue Velvet - for some reason it was iconic and special for me. First Paris. First America. An opportunity to earn money, and a lot of it. It was you who wrote: “The desire for money began to eat away at the soul.” Not Seryozha’s, of course: his soul remained free, which is why it still won’t let you go.

And one last thing. I can imagine what kind of anthill you have stirred up with your book. And how much negativity will be shed - from acquaintances, of course, because strangers will most likely perceive the text simply as an artifact; whether they like it or not is another question. So, don't worry. Seryozha didn’t make his own film, but it’s as if you did it for him. She told about herself, about him, about all the boys and girls of the Russian transitional time. It is over, gone forever. And everyone will leave - but we will remain.

Nina Agisheva

Current page: 1 (book has 14 pages total) [available reading passage: 8 pages]

Loving hurts. As if she gave permission

flay yourself, knowing that the other one

can disappear from your skin at any moment.

Susan Sontag. “Diaries”

When the coffin was lowered into the grave, the wife

She even shouted: “Let me go to him!”

but she didn’t follow her husband to the grave...

A.P. Chekhov. "Speaker"

hundred 1997, Sergei Dobrotvor died

skiy. By that time we had already been two months

were divorced. So I didn't

his widow and was not even present at

funeral.

We lived with him for six years. Crazy, happy

rainy, easy, unbearable years. It so happened that these

years turned out to be the most important in my life. Love

for him, which I cut off - with the strongest love.

And his death is also my death, no matter how pathetic it may be

During these seventeen years there was not a single day when I was with him

didn't talk. The first year passed in semi-consciousness

nom condition. Joan Didion in her book “The Year of Magic”

thoughts” described the impossibility of breaking ties with a dead

our loved ones, their physically tangible presence

near. She is like my mother after my father’s death -

couldn’t give my dead husband’s shoes: well, how could he?

after all, there will be nothing to wear if he returns - and he

will definitely return.

Gradually the acute pain subsided - or did I just

I learned to live with it. The pain went away, and he stayed with me.

I discussed new and old films with him, asked

asked him questions about work, boasted about her career,

gossiped about friends and strangers, told

about her travels, resurrected him in repeating

I didn’t fall in love with him, I didn’t finish the deal, I didn’t finish

trill, did not divide. After he left, my life changed

fell into external and internal. Outwardly I have

there was a happy marriage, wonderful children, a huge apartment

great job, fantastic career

and even a small house on the seashore. Inside -

frozen pain, dried tears and endless dia-

log with a person who was no longer there.

I'm so used to this macabre connection, this

Hiroshima, my love, with a life in which

the past is more important than the present, which I almost didn’t think about

that life could be completely different. And what

I can be alive again. And - scary to think -

happy.

And then I fell in love. It started out easy

enthusiasm. Nothing serious, just pure joy.

But in a strange way this weightless feeling, no matter what

in my soul, which has no pretense, suddenly opened in it

some kind of sluices from which poured out what had been accumulating for years -

mi. Tears flowed, unexpectedly hot. It poured

happiness mixed with unhappiness. And it’s quiet inside me, like

mouse, the thought scratched: what if he, dead, me

will he let you go? What if it allows you to live in the present?

For years I talked to him. Now I started writing to him

letters. Again, step by step, living ours with him

life that holds me so tightly.

We lived on Pravda Street. Our truth with him.

These letters make no claims to objective

portrait of Dobrotvorsky. This is not a biography, not a memoir.

ry, not documentary evidence. This is an attempt

literature, where much is distorted by memory or created

imagination. Surely many knew and loved

Seryozha is completely different. But this is my Seryozha Dobrotvor-

skiy - and my truth.

Quotes from articles and lectures by Sergei Dobrotvorsky

January 2013

Hello! Why don't I have your letters left?

Only a few sheets of your funny books have survived.

poems written and drawn by hand

creative printed font. A few notes, too

written in large semi-printed letters.

Now I understand that I hardly remember yours

handwriting No emails, no SMS - there was nothing then.

No mobile phones. There was even a pager

an attribute of importance and wealth. And we transferred the articles

Vali typed - the first (286th) computer appeared in our country only two years after

how we started living together. Then into our lives

Square floppy disks also came in, which seemed somehow alien.

planetary. We often transferred them to the Moscow

“Kommersant” with a train.

Why didn't we write letters to each other? Just

because they were always together? One day you left

to England - this happened probably in a month or

two after we got married. You were not there

not for long - maximum two weeks. I don’t remember how we communicated then. Have you called home? (We

We then lived in a large apartment on 2nd Sovetskaya, which we rented from the playwright Oleg Yuryev.) And also

you were without me in America for a long time, almost two months.

Then I came to you, but this is how we kept in touch

all this time? Or maybe it wasn't so crazy after all

needs? Separation was an inevitable reality, and people, even those impatiently in love, knew how to wait.

Your longest letter took up the maximum

half a page. You wrote it in the Kuibyshev hospital -

hospital, where I was taken by ambulance with blood

course and where the diagnosis of “frozen” was made

pregnancy". The letter disappeared during my travels, but I remembered one line: “We hold everything for you.”

fists - both mommies and me.”

Life with you was not virtual. We were sitting

in the kitchen, drinking black tea from huge mugs or

sour instant coffee with milk and talked

until four in the morning, unable to tear ourselves away from each other.

I don’t remember these conversations being interspersed with kisses.

Luyami. I don’t remember much of our kisses at all. Electric

quality flowed between us, without turning off for a second, but it was not only sensual, but also intellectual

al charge. But what's the difference?

I liked looking at your slightly arrogant

moving face, I liked your jerky

affected laughter, your rock and roll plasticity, your very light eyes. (You wrote about James Dean, whom, of course, you looked like: “neurasthenic actor

with a capricious child's mouth and sad senile

eyes”*.) When you left our home

space, then the disproportion became obvious

the awareness of your beauty to the outside world, which needs

* All quotes without references that appear in the text are taken

you are from the articles and lectures of Sergei Dobrotvorsky. – Note auto

there was always something to prove, and above all -

own wealth. The world was big - you

was small. You must have suffered from this inconsistency

dimensions. You were interested in the phenomenon of hypnotic

influence on people that makes them forget

about short stature: “Little Tsakhes”, “Perfumer”,

"Dead zone". You also knew how to bewitch. I loved

surround yourself with those who admire you. I loved it when they called you a teacher. Adored lovers

students into you. Many of your friends have contacted

to you as “you” (you to them too). Many called by

patronymic.

I never told you this, but you seemed

very beautiful to me. Especially at home where you were

proportionate to space.

And in bed there was no difference between us at all

I remember so clearly the first time I saw you.

This scene is forever stuck in my head - like

a still from a new wave film, from some “Jules”

and Jim."

I, a student at the theater institute, stand with

with their fellow students at the crossing near the embankment

Fontanka, near the park on Belinsky Street. Against

me, on the other side of the road - a short blond

Dean in a blue denim suit. I have hair

to the shoulders. It looks like yours is quite long too.

Green light - we are starting to move towards

each other. A boyish, thin figure. Springy

gait. You're hardly alone - there's a lot of people around you on Mokhovaya

There was always someone messing around. I only see you. Like a woman

finely carved face and blue (jean-like) eyes.

Your sharp gaze cut me sharply. I stopped

I’m standing on the roadway, looking around:

- Who is this?

- What are you talking about! This is Sergei Dobrotvorsky!

A, Sergei Dobrotvorsky. The same one.

Well, yes, I've heard a lot about you. Brilliant

critic, the most gifted graduate student, golden boy, favorite of Nina Aleksandrovna Rabinyants, my

and your teacher, whom you adored for

Akhmatova's beauty and for his skill the most confused thoughts

lead to a simple formula. To you with enthusiasm

aspiratedly called a genius. You're wildly smart. You

wrote a thesis on the disgraced Wajda and Polish cinema.

You are the director of your own theater studio, which is called “On the Windowsill”. There, in this

studio on Mokhovaya, a stone's throw from Teatralny

Institute (as it says on the ticket), they are studying

several of my friends - classmate Lenya Popov, friend Anush Vardanyan, university prodigy

Misha Trofimenkov. Timur Novikov, Vladimir Rekshan, the long-haired bard Frank look in there,

Maxim Pezhem, still very young, plays the guitar

skiy. My future fierce enemy and yours are hanging around there.

close friend, poet Lesha Feoktistov (Willy).

My friends are obsessed with you and your “Window Sill”

no one.” To me, who despises this kind of ritual, they remind me of sectarians. Underground films

and theater basements don’t appeal to me. I want

to become a theater historian, I excitedly rummage through the dusty

archives, I squint myopically, sometimes I wear glasses

in a thin frame (haven't switched to lenses yet) and deep

entangled in a relationship with an unemployed philosopher, gloomy and bearded. He's old enough to be my father, he torments me

me with jealousy and curses everything that somehow

takes me away from the world of pure reason (read -

From him). And the theater institute takes away - everyone

day. (No wonder the theater is in my favorite Serbian -

“a disgrace,” and the actor is a “laugher.”)

The theater institute was then, as they would say

now, a place of power. These were his last gold

days. Tovstonogov also taught here, although he lived

It didn't last long, a few months. You called him

happy death - he died instantly (about death

they say “suddenly”, they don’t talk about anything else like that

don't speak?), while driving. All the cars started moving when

the light turned green, and his famous Mercedes

didn't move. This is how Oleg Efremov’s hero dies

driving an old white Volga in a film with unbearable

with the same name “Extend, last,

charm” - to the then hysterically cheerful

Valery Leontiev’s hit “Well, why, why, why”

Was the traffic light green? And because, because, because

he was in love with life.”

We went to rehearsals with Katzman. His previous

The next course was the star course of the Karam Brothers

calling” – Petya Semak, Lika Nevolina, Maxim

Leonidov, Misha Morozov, Kolya Pavlov, Seryozha

Vlasov, Ira Selezneva. Katzman loved me, often

stopped on the institute stairs and asked

questions, was interested in what I was doing. I'm sick

she was infinitely shy, babbling something about the topics of her

coursework. He taught together with Katsman on Mokhovaya

It was then that Dodin released “Brothers and Sisters,” which we went to see ten times. The best teachers

were still alive - the theater students were thrilled

from the lectures of Barboy or Chirva, there was a feeling in the audience

erotic vibes. Student actors were running around

with his unembodied talents and unclear

future (about the brightest they said: “What a beautiful

no texture!"); female art students wore long

skirts and homemade beads (you called this style

dress “Ganges store”); student directors led

conversations about Brook and Artaud in the institute cafeteria

over a glass of sour cream. So the Leningrad theater,

and LGITMiK (it changed so many names that

I'm confused) were still full of life and attractive

gifted and passionate people.

Then, on Fontanka, when I stopped

and turned around, I saw that you had turned around too.

In a few years everyone will be singing: “I looked back

to see if she looked back, to see if I looked back.” I thought you looked

almost contemptuously at me. With your little

growth - from top to bottom.

You told me later that you don't remember this

meeting - and that he actually saw me in the wrong place

and not then.

It's such a shame that you weren't with me today.

I went to the David Bowie exhibition in London

Victoria and Albert Museum. I've heard so much about her

and I read that it seemed like I had already been there. But, having

Sitting inside, I felt that I was about to lose

consciousness. There were so many of you that I created this exhibition

slipped almost tangentially, unable to let in

into yourself. Then she sat somewhere on the windowsill of the

morning museum courtyard and tried to keep

tears (alas, unsuccessfully).

And it's not that you always admired Bowie

and he looked like Bowie himself. “A fragile mutant with a rabbit-

through whose eyes” – that’s what you once called him. And not

is that your collages, drawings, even your semi-

the printed handwriting was so reminiscent of his. And not even the fact that for you, as for him, the express meant so much

Zionist aesthetics, so important were Brecht and Berlin, which you called a ghost town full of

pathos, vulgarity and tragedy. The point is that life

Bowie was an endless attempt to transform herself

into a character, and life into a theater. Run away, hide, reinvent yourself, deceive everyone, shut down

I found your article about Bowie at 20

prescription “Cinematography, by definition, was and remains

is the art of physical reality, with which

Bowie struggled for a long time and successfully, synthesizing his own

new flesh into some kind of artistic substance.”

I remember how you admired his colorful

eyes. He called him the divine androgyne.

How I admired his character - the icy blonde

beast - in a speculative and static film

Oshima’s “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,” which you loved for the inhuman beauty of the two

main characters. Like they said it's a vampire kiss

Bowie with Catherine Deneuve in “Hunger” is perhaps the most

beautiful screen kiss. Then all this doesn't bother me

was too impressive, but now it suddenly hit

straight into the heart. And in the same article of yours I read:

“Cinematography has never grasped the law according to which

this ever-changing body lives. But who knows, maybe right now, when virtual reality

ness has finally replaced the physical, we are all

we will finally see the true face of the one who does not throw away

shadows even in the blinding beam of a film projector.”

Why, why are these stupid tears flowing from me?

You died, he is alive. Happily married to a gorgeous

Iman has settled down and regained his full physical

reality - and somehow lives with its virtual

And you died.

I miss you so much today! I was rummaging through the net - suddenly

Is there something I don’t know about you at all? Found it

letters from Lenka Popov, a brilliant theatrical

critic, one of those who called you a teacher.

He died two years after you - from leukemia.

They say that on the eve of his death he asked for a theater

poster - I was sure that by the end of the week I could

go to the theater. He was thirty-three, less than

to you at the time of your death. He died so absurdly, so early. Why? He did not run away from himself (you wrote that

the romantic hero always runs from himself, which means in a circle), did not comprehend his adored

theater as a tragic medium. But what did I know about him?

I missed Lenka’s letters then. I am so much

years after your death I lived like a somnambulist - and so

a lot of things slipped past me. In one letter

Lenka writes to her friend Misha Epstein, this

1986: “Bear, have you seen this man?! So what

talk here? Should we talk about how happy he is?

work, communicate with him and in general?.. If he is far away

not a mediocre actor, a brilliant organizer (this is half-

the director's success), a great teacher, invariably

ascended storyteller, interlocutor and drinking companion,

a great connoisseur of modern art, philosophy, music - well, why list all his advantages?

After meeting with him, we met with Trofimenko-

you were about six months old and couldn't speak

about nothing but him.”

It seems that it was Lenka, your fanatical student

idiot, dragged me to the premiere of Vonnegut's play

“Happy Birthday Wanda June!” in your studio theater

“On the windowsill.” (Here I habitually wrote “Lenka”

and remembered that Popov always passionately defended

the letter “e”. So - after all - Lyonka.) Or maybe

maybe Anush, a friend of my first year, called me

institute life. In Armenian, bright Anush nosi-

la bold crimson raincoat pants that

I borrowed from her at crucial moments and played

in “Wanda June” the main female role. you later

told me more than once that the director must be in love

with his actress, and I think he was a little in love

in Anush. I went to this performance reluctantly, nothing

not expecting anything good. I felt instinctive

rejection from all amateurism - from parallel

from cinema to underground theatre. passed me by

the euphoric stage of group unity that you probably need to go through in your youth. I'm stories -

I told you that as a child I roared in horror at the demonstration

tions, I was always afraid of crowds and never fell in love

big companies. “Every herd is a refuge

lack of talent,” I quoted Pasternak. And still

I'm running away from everywhere now. That is, I even succeed

have fun, especially if I drink a lot of champagne

oh, but the moment quickly comes when I need to be quiet

disappear. When we were together you always left

with me. And when you were without me, did you stay?

Your play “Wanda June” was performed in the summer

eighty-five. So I was nineteen

twenty years old - like Trofimenkov, and Popov, and Anush.

And you are twenty-seven. Well, you seemed to me

so grown up, despite your boyish appearance.

They gave me a program printed on a photocopier, from which I learned that you drew it yourself. And what

you yourself will play one of the roles - the hanged man

a Nazi major who came from the other world. And the costumes

made by Katerina Dobrotvorskaya – it seems exactly

That's how I first found out that you have a wife.

They showed me their wife - in my opinion, she also appeared

appeared in the play in a small role. But on stage I don't have it

I remember. I was amazed at how tall she was - taller

me - and much taller than you. Dark, thin, with a hoarse

From what happened on stage, I didn’t like

nothing happened. Abstruse text, wooden Anush, more

some people, clumsily painted. I was

It's awkward to watch the stage. Lenka Popov in one of

wrote letters that the process fascinated you more than

result. I'm so ashamed now that I never speak

talked to you about this studio, about this performance, brushed aside

I dismissed them as if they were amateurish nonsense. You, with yours

pride, knowing my attitude, also not about it

remembered. I crossed out a whole one - so huge -

a theatrical piece from your life. I thought he was under-

worthy of you? She was jealous of the past, where I was not

was? I was indifferent to everything that directly affected me.

really didn't concern? Or - as always - I was afraid

any underground, feeling danger, realizing that I

there is no place, that there you are eluding me - and there

will you eventually leave? I would really like to sit down now

with you in the kitchen over a mug of cool black tea (on

your favorite mug had the Batman emblem) and that’s it

to ask you. How did you find this studio? Why

decided to make Vonnegut? Why did you choose such a boring

new play? And how this basement was taken away, and how you ran to the regional committees to fight for it and tried

charm the aunts with challah on their heads (I found out about this

only from your short letters to Lyonka Popov

to Army). And is it true that you were in love with Anush?

Would you give this role to me if I came along?

with her to your studio “On the windowsill”? And how are you on

did you spend your days and nights on this windowsill? Everyone, of course, looked at you with delighted eyes, their mouths open?

Were you swollen with pride and happy? Nothing

I never asked, editing like a pig

your life, which didn’t fit into my scheme.

Yes, everything in this basement studio (pretty painful)

beautiful and even unexpectedly light) it seemed to me

dreary and meaningless. Everything except you. You

appeared in a black shirt, covered in blood, with stains

lazy and painted like on Halloween, wearing women's boots and holding a toy monkey in his hand.

The demonic makeup was not scary, but funny, but to me

for some reason it wasn't funny. Now I'm sure that you

I did my makeup with Bowie, but then I hardly knew who he was. The energy coming from you was like this

so strong that it gave me goosebumps. I remember-

Nila your sharp gaze then, on the Fontanka. When you

went on stage, I also acutely felt your physical

ical presence.

I always believed only in the result, I didn’t care

new process. I didn't recognize geniuses until

I wasn't sure that they actually created something

brilliant. I left this performance with a feeling

I eat that I watched nonsense created by an outstanding

human.

I'm sorry I never told you this.

I haven't talked about you to anyone for many years. With no one.

I could quote you or remember one of

your brilliant remarks. But no, I couldn’t talk about you. It hurt too much. There was a feeling that by doing this I was betraying you. Or I share it with someone. Even

if your parents said something like “But

Earring would probably be right now...” I was silent in response.

And suddenly – I spoke. I was surprised to discover

lived that not only do I not feel pain when pronouncing your

name or a strange phrase “my first husband,” but I even enjoy it. What is this?

Why? Is it because I began to write to you (and about you), little by little releasing my demons? Or because

I fell in love?

Today I saw Tanya Moskvina for the first time in

many years. You studied at the institute together, you admired

admired the power of her critical gift and ability

fear nothing and no one. Tanka always cut

the truth, was irrational, biased

and clearly suffered from the fact that her subtle soul was placed

into an incongruously large body (you probably do the same

suffered from its “pocket” size). Once, when my son Ivan was still very small,

Moskvina came to visit me. Ivan carefully

looked at her bright asymmetrical face. She's like

I, too, suffered from facial neuritis in my youth. When

I was brought in at the age of eighteen with half a para-

lized person to the hospital, the nurse records-

who gave my details, asked: “Are you working?

Are you studying?” – “I study at the theater institute,

Faculty of Theater Studies." - “Thank God that on

theater studies You won’t make an actress now, with such and such a face.” What won't come out of me now?

gray woman and that is much bigger for me

drama, she was not interested.

- Why is one eye smaller than the other? -

Ivan asked Moskvina.

- Now I’ll hit you in the eye, and you’ll have it

the same thing,” Tanka immediately retorted. What

this is not usually said to small children, she

and it never occurred to me. So she lived - in nothing

no restrictions. You're your rebellious nature

painfully tamed, and was also delicate

and didn't like to offend people. And Tanka allowed herself

always and in everything be yourself and do nothing

half. If it’s a bottle of vodka, then it’s all the way to the bottom. If

passion - until the bitter end. If hatred is

then right down to the livers. She knew how to be so delightful

free and so obsessively wrong that you're a little

I envied her. She always gave you credit, as if your blood type was mixed with

St. Petersburg patriotism was the same.

Today Moskvina told me how you first

showed me to her - in the library of the Zubov Institute

on Isaakievskaya, 5, where you and her go twice a week

went to the presence.

“Look, what a girl,” you said proudly. -

This is Karina Zaks. She is very interested in rock culture.

– Did our romance already begin then? – asked

- It seems not. But he was already clearly in love.

Well, yes, rock culture, of course. In the third year

training, I wrote a term paper called

"Catcher in the rye". It was fashionable then to talk

about youth culture. Alternative youth, who show contempt for society in various ways

for some reason they called it a system, and furry tattoos

young men who chanted “We

together!" at “Alice” concerts, - by system specialists

(nowadays the system is called those who group

around power and money, and system specialists – those who

tidies up computers). “The world as we knew it is coming to an end,” with a special Leningrad approximation.

Grebenshchikov sang with his breath, throwing back his head and closing

howling eyes. He was the first rocker whose tape

I listened to it ten times a day, not yet knowing how he

golden-haired and good-looking. The Leningrad rock club, which plunged us into sexual ecstasy, the Latvian car-

Tina “Is it easy to be young?”, Tsoi, similar to

Mowgli and the always black-clad, mad Kinchev

with eyeliner in the film “Burglar”, re-

dachas “Vzglyad” and “Musical Ring” in Leningrad-

com television, where grown men condescendingly

tried to deal with the informals and somehow formalize

matte rockers (the easiest way to format this is

of course, BG succumbed to this

the system always didn’t care). I wrote a passionate

term paper in the first person, where my dad expressed

the vulgar conciliatory ideas of the older generation, where

the institute's cloakroom attendants scolded the disgusting hair-

that youth and where are the quotes from “Aquarium”, “Alice”

and Shinkarev’s “Mitki” were illustrated by my most

clear thoughts about spiritual freedom. This one is choking

The student’s work was liked by the supervisor

critical seminar to Tatyana Marchenko. She showed-

laed it to Yakov Borisovich Ioskevich, who together

I collaborated with you on a collection of articles about youth culture.

I was summoned to Isaakievskaya - to meet with you

both. I prepared for this meeting, mercilessly

curled her long hair with hot curling irons, blushed

I covered my cheeks with cotton wool and painted my eyelashes thickly (I needed mascara

diluted with saliva) and applied foundation in layers

cream. Why I did this - I have no idea, my skin

It was perfectly smooth and did not require makeup.

But since childhood, it seemed to me that I could be better, more beautiful, I wanted to bridge the gap between what I really was and what I could be, if... If only what? Well, at least the hair was curlier, the eyes were bigger, and the cheeks were rosy. As if spreading

face with foundation (a product of joint creativity

L'Oreal and the Svoboda factory, of course, is incorrect

a different shade, much darker than my pale skin required.

skin), I was hiding under a mask. At the same time I put on

Six-zip jeans - youth culture

after all. It wasn't a beetle that sneezed.

I was sure that you would praise me, because

not every third-year student is going to print

appear in an adult scientific collection. You have entered

pulpit, looked me up and down with an icy gaze (I asked

yourself, do you remember our meeting on the Fontanka) and said arrogantly:

– I’m not a fan of a writing style like yours.

I was silent. And what could be the answer? I

I thought I had written something really cool.

And in general, I didn’t ask to come here, you called me.

– You write in a very feminine, hysterical and emotional way.

rationally. Very snotty. Lots of stamps. And besides

“But this will have to be cut in half,” saying

all this, you hardly looked at me. You said later

to me: “You were so regal and beautiful that

I was completely confused, I was rude to you and even looked at

I was afraid of you.”

I continued to remain silent. At this moment to the pulpit

Yakov Borisovich entered.

- Oh, so you are the same Karina? Beautiful

work, wonderful. Will greatly decorate our collection -

written so passionately and with such personal intonation.

I remember that I felt gratitude to him

and resentment towards you, who at this moment is indifferent

looked out the window.

I actually cut the text in half. But

I didn’t remove my father and his lines from the ending

from the repertoire of the then “daddies” (“daddy’s” at that time

time was called not only cinema). This ending is for you

seemed stupid, but to me it seemed principled, because

didn't last long, I couldn't forget how you were with me

got by. Since then it seemed to me that you continued

despise me, and when I met you somewhere, I was like

style...” And muttered under her breath: “Well, I’m not a fan

your intellectual tediousness.”

But I have already begun to understand the price of this tediousness.

Hello! I start a letter and am lost - how can I contact you?

address? I never called you Seryozha or

Serezhka. And I certainly never said Sergei.

When you lectured with us, I could turn to you

“Sergey Nikolaevich.” However, hardly; Most likely, I avoided the name because I already understood that between

we have a space where patronymics are not

relies. I never addressed you by your last name, although your other girls - before me - did this.

Your first wife Katya called you “Dobsky” -

I always shuddered at this dog's name.

Or maybe just out of jealousy.

It only recently dawned on me that none of the

I couldn’t call my beloved men by name, as if I was afraid to touch something very secret.

And none of them called me Karina to my face; they always came up with some gentle or funny

nicknames But when they did call it, it hurt

me as something almost ashamed. Or maybe I just

names were needed that would only be

ours - not worn out by anyone.

When we started living together, pretty soon

began to call each other Ivan. Why Iwanami?

It's a shame, I don't remember at all. I don't remember how

and when this name made its way into our vocabulary. But I remember

all its modifications are Ivanchik, Vanka, Vanyok, Vanyushka, Ivanidze. Always in the masculine gender. And I remember how we once began to laugh when I first called

you with Ivan in bed. You didn't like to talk

in bed? And I also remember how your mother, Elena Yakov-

Levna roared into the telephone receiver:

– You named your son Ivan, right? In honor of

It was the day I learned of your death.

When did I fall in love with you? Now it seems to me that

I fell in love at first sight. And that each one follows-

This meeting was special. Actually at that time

I was in love with someone else whose value system

accepted unconditionally. I felt you keenly, that's for sure. But several more years passed before

than I realized that this was love.

This happened when you were giving lectures on

history of cinema, replacing Yakov Borisovich Ioskevich.

I was in my last year, so I was about a year old

twenty two. And you, accordingly, are thirty, quite a serious age. We like Ioskevich's lectures.

curled up, but seemed too abstruse. When in-

one hundred you came and said that Yakov Borisovich

ill and that you will conduct several classes, we

rejoiced.

You stunned us - just as you stunned all of yours.

students. Nervous beauty, mesmerizing

plastic hands, an unusual combination of unscrewed

style and composure, energy, erudition. We are told

It seems that you went through all the tiny cubes

I'm waiting for my voice to come back. The words will probably come back with him. Or maybe not. Maybe you will have to be silent for a while and cry. Cry and remain silent. A person uses words to cover up embarrassment, to plug up the black hole of fear, as if this were possible. My friend wrote a book and I just read it. Tomorrow (today) I have to submit the script, and I recklessly dived into Karina’s manuscript. I emerge in the morning - dumbfounded, speechless, helpless. There is no one to help me. Seryozha is dead, Karina... What time is it in Paris? Minus two. No, it's early, she's sleeping. And I don’t want to talk. Impossible to talk. My friend wrote a book. And all I can do now is describe my crying. An ancient woman's cry.

Karina and I had a short but incredibly acute “attack of friendship.” As if our friendship at that time was some kind of exotic disease, which our healthy and young organisms later coped with. They managed to cope, they even developed a strong antigen, but later it turned out that each of us carries the virus of attachment within us - for life. Many things happened to us at the same time, in parallel. We trained our love muscles often on the same objects, we suffered like children from the same diseases, including jaundice (at the same time) and appendicitis (within a week of each other). And after thirty years of dating, we wrote a book. I - a little earlier, my “Wax” was already published. Both books are about death and love and about the only possible sign of equality between them. “I wrote it a little earlier” - this means: I screamed a little earlier from the horror that was revealed in myself, from the inability to hold back the scream. She screamed earlier, like a twin born ten minutes early.

Karina's book concerns me in exactly the same way as her life concerns me. Like the life of Seryozha, Sergei Nikolaevich Dobrotvorsky, like his death, concern me and many others. “Touches” is not only “has a relation,” it means “touches” and with its touch causes pain, almost voluptuous, erotic, equal to pleasure. After all, you have to be able to write like this, discarding any hint of stylistic beauty or cleverness! And in order to have the right to write like this about the main event of your life, about the main sin for which you punished yourself for years, you need to live the life of Karina Dobrotvorskaya, which is impossible for an outsider. And my night cry, the cry of the first morning after reading “Letters to Seryozha” was: “My poor one! What have you done with your life?!”

They were together, she left, he died a year later - the bare facts."Has anyone seen my girl?" This courageous girl? This bitch? This angel?

One day, a mutual friend of Karina and I, listening to another exciting story about our early love escapades, suddenly asked: “I don’t understand. Here too (he studied at some technical university), girls fall in love, and go to parties, and suffer, and talk about it. But why does it come out so beautifully for you, but usually for them?!” The question was rhetorical, but it caused cheerful laughter and youthful pride. Yes, we are!

In this logic, the meeting of Karina and Seryozha, romance, marriage, partnership were as if predetermined. No, this was not engraved in imperishable gold letters on some cosmic tablets. “We should have met” - this, in my understanding, is pure logic. After all, “that’s who we are!”, everything should be the best for us, and I don’t remember anyone better than Seryozha at that time. The sacred berry of eros within these relationships remained uncrushed, unrotted until the very end. Between these people lived something that cannot be profaned. And he still lives.

And it was also not surprising that they broke up. It was a pity, it was painful, as if it was happening to me (I was talking about parallels: on those same days I was experiencing my own painful breakup), but not surprising. Love is full of pain. This is among other things.

Hey, somebody! Has anyone seen this steely woman with the eyes of a frightened teenage deer? She executed herself all her life - effectively, terribly, burning out feelings in herself, like some mystical vivisector from a horror movie about the Alien - with fire, napalm. And every line of the book is the chronicle of a survivor in the desert. And then the execution suddenly became public. And saving. Speak, people, rage, get angry, condemn, but she did it - she wrote about him, about herself and about eternal love.

The point is not in the documentary (although the book is documentary) or even in the veracity (factual and emotional) of the memories. The point is the impossibility of losing them and the impossibility of storing them. And another thing is that the deceased Seryozha did not die. He is the only reality in which Karina is confident, in which she lives.

I noticed: people are horrified by the truth, any hint of it. Despite the plebeian cult of “sincerity,” the truth—the transparent, visible and inextricable connection between a phenomenon and the word by which the phenomenon is called—is frightening. People, good, caring people, begin to look for the reasons for the emergence of a truthful statement. And they are found, of course, most often in negative space. “What kind of dancing on bones?!”, “She’s doing this for self-PR!”, “I should think about my husband and children!” This is the little that I heard when Karina's book came out. And the people are all wonderful, but they are very caring. As a rule, they did not read the book itself, limiting itself to the summary. But everything is already clear to everyone. Everyone already has ready-made answers. But I know: words grow like a palisade, fencing off from meaning, from authenticity, from human sovereignty. Otherwise, you need to confront yourself with the obviousness of a disappointing fact: everything is not so simple, and life is blood and tears, and love is pain and chaos.

In his last spring, we met on the set of a small film that my classmate was filming. Seryozha agreed to appear in a cameo. Between shots, between shots of his whiskey, he suddenly asked: “How are you?” - "Fine". He twisted his mouth in disgust: “Yes, I was told that you are holding on.” He was referring to my own breakup and my laments about it. I was surprised. Who did you hear it from? And if this is called “holding on,” then I’m already losing the meaning of the words. But I answered, proud of myself: “Yes, I’m holding on.” - “But I’m not.” All. Dot. He doesn't.

Has anyone seen a girl with a stone in her palm? With the stone she kills herself with every day, trying to reach her own heart? Calling a spade a spade is a thankless and cruel undertaking. Truth - this means to bypass, stop lengthy explanations, motivation and review of long-term goals. There is only the past, perhaps the present, and, strangely enough, there is probably a future. The connection between them is not obvious, although it is often equated to an axiom. Only one thing can connect them, passing through the past, present and illusory future, something unique, something unique, each has its own - hope, for example. Blessed is he who believes... For Karina, this is pain, the utter pain of enduring love. Has anyone seen a beautiful girl without illusions and hope? She is here, she stands and waits for the pain to subside.

Karina Dobrotvorskaya. “Has anyone seen my girl? One hundred letters to Seryozha."

Publishing house "Editing Elena Shubina"