The goals of Stolypin's agrarian reform. Agrarian reform P.A.

Read also

a set of interrelated measures for the restructuring of all components of the economic mechanism - organization, management, economic relations, forms of ownership and management, land relations, etc. 1990). Developed by a team of scientists from the Belarusian Research Institute of Economic Problems of the Agroindustrial Complex, specialists from the State Committee for Agriculture and Food with the participation of employees of the State Plan and the Research Economic Institute of the State Planning Commission. It outlines the issues of the formation of a new agrarian policy in relation to the transition period and the market economy. Contains sections: “Principles of the reform of relations in the agro-industrial complex. Political premises and their probable consequences ”,“ Property. Land ownership and reform. Denationalization and privatization "," Creation and development of peasant farms "," Formation of food stock "," Price mechanism. Price parity ”,“ Financial and credit relations and tax policy ”,“ Improvement of investment policy ”,“ Strengthening motivation and stimulation of labor ”,“ Development of social infrastructure ”,“ Personnel training ”,“ Organization of management ”,“ Target programs: “Fertility "," Grain "," Potatoes "," Vegetables "," Fruits and Berries "," Sugar "," Feed "," Flax "," Meat "," Milk "," Foreign Economic Relations ". The program provides a characteristic of the pre-market state of the agricultural economy of the republic. In 1991, the State Program for the revival of the Belarusian countryside was developed and approved by the Council of Collective Farms. It defines the priority areas of capital investments in the non-production sector, the volume of construction and commissioning of healthcare and education facilities, trade and everyday life, and preschool institutions. The expediency of construction in rural areas of a comfortable manor-type housing with autonomous engineering arrangement, the use of electricity and gas for domestic purposes is argued. The task has been set to transfer the communal services to self-sufficiency, to bring in proper order the internal road network and streets. In 1994, scientists of the Belarusian Research Institute of Economic Problems of the Agroindustrial Complex developed and approved at a joint meeting of the Board of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Presidium of the Academy of Agrarian Sciences of the Republic of Belarus the Concept of agrarian reform in the Republic of Belarus (Resolution No. No. 14/20). The concept contains the main provisions for improving the organizational and economic mechanism of the functioning of the agro-industrial complex in the context of its transition to a market economic system. It proposes a system of views on the following issues: denationalization and privatization, transformation of forms of management, establishment of farming, development of land relations, formation of a system of financing and pricing, taxation and lending to enterprises, activation of their investment, restructuring of the existing system of material and technical supply and agricultural services, regulation of employment , the formation of the food fund, the development of cooperation and integration, the non-production sphere of the village. A benchmark was taken on the republic's self-sufficiency in food, agricultural raw materials, taking into account the economic feasibility of their production, which contributes to ensuring national food security. The scientific and practical basis for reforming the agrarian sector in the republic was the State Program for Reforming the Agroindustrial Complex of the Republic of Belarus, approved by the Collegium of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus on August 6, 1996. The main goal: a gradual transition in the field of agro-industrial production from a command-administrative to a market system of management, which presupposes the free functioning of economic entities. subjects within the legal corridor under the state regulation of certain aspects of activities (see the State program for reforming the agro-industrial complex). Over the past period, the main stages of the agrarian reform can be distinguished: 1991-1992. - awareness of the sovereignty of Belarus, orientation of the mentality of the population and rural commodity producers to the development of market methods, emphasis on the formation of alternative forms of management. 1992-1995 - a sharp reduction in state subsidies to agriculture, the state's withdrawal from the problems of the agricultural economy, the accelerated destruction of the production potential of large agricultural enterprises, the beginning of a broad transformation of collective and state farms into market-type forms on a share and share basis, creating conditions for the development of farms. 1995-1998 - recognition of the diversity and diversity of agriculture, alignment of state policy in relation to various forms of farming, rehabilitation of the role and significance of large-scale production, gradual restoration of the system of direct centralized management of the economy (with a sharp shortage of material and technical resources and financial resources), increase in debt credit and loan enterprises and aggravation of insolvency problems. 1999-2000 - strengthening state centralized financial support for agriculture, an attempt to stabilize production, creating a mechanism for the country's food security and using elements of interventional regulation of the agro-industrial complex, adopting a program and a development forecast, giving priority to efficient production. In 2000, the Republican program for increasing the efficiency of the agro-industrial complex for 2000-2005 was developed and approved by the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus. Includes the main directions of development: 1. Economy and organization of the agro-industrial complex (food security - a strategy for the development of the agro-industrial complex; improving the economic mechanism; reforming agricultural enterprises). 2. Accommodation and area specialization. 3. Agriculture and plant growing (structure of sown areas; selection and seed production, grain, oilseeds, sugar beets, potatoes, flax, forage; development of fruit growing, vegetable growing; land reclamation and use of reclaimed land, etc.). 4. Development of animal husbandry (intensification of milk production, development of breeding and reproduction of the herd, development of poultry farming, etc.). 5. Mechanization and energy of agriculture. 6. Processing and food industry. 7. Development of the bakery industry. 8. Priority areas of investment. 9. Foreign economic activity. 10. Scientific support. 11. Information system of the agro-industrial complex. 12. Agrarian education and staffing. 13. Applicable and required legislation. The program did not become the main guideline for the development of the agro-industrial complex, did not find reflection in legislative acts and decisions of local government and economic management bodies. In 2001, the Program for improving the agro-industrial complex of the Republic of Belarus for 2001-2005 was developed and approved by the Decree of the President of the Republic of Belarus. The main goal: to form a micro-and macroeconomic economic system that ensures sustainable development and a consistent increase in the efficiency of agro-industrial production, a guarantee of food security of the state by increasing the volume of agricultural production to a level that ensures a minimum level of food security. In 2005, by the Decree of the President of the Republic of Belarus (dated September 14, 2003, No. 37), the State Program of Rural Revival and Development for 2005-2010 was approved. (see State Program of Rural Revival and Development for 2005-2010). During the years of agrarian reforms, contradictory processes took place, however, positive, qualitatively new phenomena were able to manifest themselves, in particular: conditions were created for multi-structure and diverse forms of management were formed; legal guarantees have been created for the equal development of two forms of ownership - state and private (the absolute majority at present are non-state agricultural enterprises; about 17% of land is privately owned); the foundations for the gradual formation of a new mentality of the population and commodity producers based on the laws and principles of a market economy have been formed; revived economic relations, providing for earning money, self-employment, self-regulation and self-management; methods of economic activity are involved, causing resource conservation and cost savings, rational use of resources and optimization of the return on investment; efforts were made to restructure production to meet market consumer demand and sales; measures were taken to master the foundations of agribusiness, entrepreneurship and foreign economic activity, commercial settlement and competition; mastered the methods of direct contractual economic relations between business partners and market counterparties, etc.

The reform of peasant land tenure in Russia, which took place from 1906 to 1917. Named after its initiator P.A.Stolypin. The essence of the reform: Permission to leave the community for farms (decree of November 9, 1906), strengthening of the Peasant Bank, compulsory land management (laws of June 14, 1910 and May 29, 1911) and strengthening of the resettlement policy (transfer of the rural population of the central regions of Russia to permanent residence in sparsely populated outlying areas - Siberia, the Far East and the Steppe Territory as a means of internal colonization) were aimed at eliminating peasant land shortages, intensifying the economic activity of the peasantry on the basis of private ownership of land, and increasing the marketability of the peasant economy.

To carry out his reform, Stolypin skillfully used economic and political “trump cards”. He used for his own purposes both the fragmentation of the revolutionary opposition and the lack of agreement among the radical intelligentsia.

1905-1911 became the years of decline of the revolutionary movement. In the party of Social Democrats, there was a final split on the issue of the possibility of continuing the social. revolution in Russia. Also, the implementation of Stolypin's plans was facilitated by the economic recovery in the country. At this time, there was an increase in nationalism. The bourgeoisie strove to get rid of the presence of foreign capital.

the main objective was to expand the social. bases of the regime at the expense of broad strata of the peasantry and prevention of a new agrarian war, by transforming the majority of the inhabitants of their native village into "a strong, imbued with the idea of property, rich peasantry," which, according to Stolypin, makes the best stronghold of order and tranquility. " In carrying out the reform, the government did not seek to affect the interests of the landowners. In the post-reform period and at the beginning of the 20th century. The government was unable to protect the noble landownership from the reduction, but the large and small landed nobility continued to constitute the most reliable support of the autocracy. To push him away would be suicide for the regime.

Another purpose was the destruction of the rural community in the struggle of 1905-1907. , the reformers understood that the main thing in the peasant movement was the question of land, and did not immediately seek to destroy the administrative organization of the community. Socio-economic goals were closely related to socio-political. It was planned to liquidate the land community, its economic land distribution mechanism, on the one hand, which constituted the basis of the social unity of the community, and on the other hand, hindered the development of agricultural technology. The ultimate economic goal of the reforms was to be a general rise in the country's agriculture, the transformation of the agricultural sector into the economic base of the new Russia.

Organization of farms and cuts.Without land management, technical improvement, the economic development of agriculture was impossible in the conditions of peasant patchwork (23 peasants of the central regions had plots divided into 6 or more strips, in various places of the communal field) and were far away (40% of the peasants of the center should were weekly to pass from their estates to allotments 5 and more versts). In economic terms, according to the plan of Gurko, strengthening without land management did not make sense.

Reform progress.

The legislative basis for the reform was the decree on November 9, 1906, after which the reform began to be implemented. The main provisions of the decree were enshrined in the law of 1910, approved by the Duma and the State Council. Serious clarifications in the course of the reform were introduced by the law of 1911, which reflected a change in the emphasis of government policy and signified the beginning of the second stage of the reform. In 1915-1916. in connection with the war, the reform actually stopped. In June 1917, the reform was officially terminated by the Provisional Government. The reform was carried out by the efforts of the main department of land management and agriculture, headed by A.V. Krivoshein, and the Stolypin Minister of Internal Affairs.

Organization of farms and cuts ov. In 1907-1910, only 1/10 of the peasants, who strengthened their allotments, formed farms and cuts.

Resettlement beyond the Urals. By decree on March 10, 1906, the right to resettle the peasants was granted to all comers without restrictions. The government allocated considerable funds for the costs of settling settlers in new places, for their medical care and public needs, for the construction of roads. The results of the resettlement campaign were as follows. First, during this period a huge leap forward was made in the economic and social development of Siberia. Also, the population of this region during the years of colonization increased by 153%.

Destruction of the community... For the transition to new economic relations, a whole system of economic and legal measures was developed to regulate the agrarian economy. The decree of November 9, 1906 proclaimed the prevalence of the fact of sole ownership of land over the legal right to use. The development of various forms of credit - mortgage, land reclamation, agricultural, land management - contributed to the intensification of market relations in the countryside.

In 1907 - 1915. 20% of the householders stood out from the community. New forms of land tenure became widespread: farmsteads and cuts.

Purchase of land by peasants with the help of a peasant bank... As a result, if until 1906 the bulk of land buyers were peasant collectives, then by 1913 79.7% of buyers were sole peasants.

Cooperative movement. Many economists have come to the conclusion that it is cooperation that is the most promising direction in the development of the Russian countryside, meeting the needs of the modernization of the peasant economy. Credit relations gave a strong impetus to the development of production, consumer and marketing cooperatives.

The peasant sector in Russia is making significant progress. A large role in this was played by the harvest years and the rise in world grain prices, but the cutting and farmsteads, where new technologies were used to a greater extent, were especially progressing. The yield in these areas exceeded those of the communal fields by 30-50%. The export of agricultural products in the pre-war years increased even more, by 61% compared to 1901-1905. Russia was the largest producer and exporter of bread and flax, a number of livestock products. So, in 1910, the export of Russian wheat amounted to 36.4% of the total world export.

But this does not mean that pre-war Russia should be presented as a "peasant paradise". The problems of hunger and agrarian overpopulation have not been resolved. The country continued to suffer from technical, economic and cultural backwardness. The growth rate of labor productivity in agriculture was relatively slow.

But a number of external circumstances (Stolypin's death, the outbreak of war) interrupted the Stolypin reform. Stolypin himself believed that the success of his undertakings would take 15-20 years. But even in the period 1906-1913, a lot was done.

Social outcomes of the community's fate.

The community as a self-governing body of the Russian village was not affected by the reform, but the socio-economic organism of the community began to collapse

Socio-political results of the reform.

* Growth of the economy * Agriculture has become sustainable

* The purchasing power of the population has increased

* Increased foreign exchange earnings associated with the export of grain

* Farms started only 10% of farms * Wealthy peasants more often left the community than poor peasants * 20% of peasants who took out loans went bankrupt * 16% of immigrants returned back

* Accelerated bundle

* The government did not satisfy the needs of the peasants in land. In 1917 it became obvious that the agrarian reform was 50 years late.

Historical significance of the reform... Stolypin's agrarian reform is a conditional concept, because it does not constitute a whole concept and is divided into a number of separate measures. Stolypin did not even allow the thought of the complete elimination of landlord ownership. The immigration epic of 1906 -1916, which gave so much to Siberia, had little effect on the position of the peasantry in central Russia. The number of those who left for the Urals was only 18% of the natural increase in the rural population over the years. With the beginning of the industrial upsurge, migration from the countryside to the city increased.

Despite favorable economic and political circumstances, Stolypin nevertheless made a number of mistakes that put his reform in jeopardy. Stolypin's first mistake was the lack of a well-thought-out policy towards workers. Stolypin's second mistake was that he did not foresee the consequences of the intensive Russification of non-Russian peoples. He openly pursued a nationalist Great Russian policy and set all national minorities against himself and against the tsarist regime.

The most important of the complex of reforms conceived by P.A.Stolypin, of course, was agrarian reform.

The main provisions of the reform

The essence of the Stolypin reform was to keep landlord ownership intact and resolve the agrarian crisis at the expense of redistribution of communal peasant lands between peasants. Preserving landlord ownership, PA Stolypin protected the social stratum of landowners as the most important support of tsarism, given that as a result of the revolution of 1905-1907. the peasantry was no longer such a support. PA Stolypin hoped that the stratification of the peasantry due to the redistribution of communal lands would create a layer of new proprietors - fsrmsr as a new social support of power. Consequently, one of the most important goals of the Stolypin reform was, ultimately, the strengthening of the existing regime and the tsarist power.

The reform began with the publication on November 9, 1906 of the Decree on the additions of some provisions of the current law concerning peasant land tenure and land use. Although the Decree was formally called additions to the regulations on the land issue, in fact it was a new law that radically changed the system of land relations in the countryside.

By the time the law is promulgated, i.e. by 1906, in Russia there were 14.7 million peasant households, of which 12.3 million had land plots, including 9.5 million households on communal law (mainly in the central regions, the black earth belt, in the North and partially in Siberia) and on household law - 2.8 million households (in the Western and Vistula regions, the Baltic states, Right-Bank Ukraine).

The decree of November 9, 1906 provided the peasants "with the right to freely leave the community, with the consolidation of secular land plots into the ownership of individual householders, passing to personal ownership." Those leaving the community were assigned lands that were in their actual use, including those leased from the community (in excess of the allotments that were relied on), regardless of the change in the number of souls in the family. Moreover, in communities where there was no redistribution for 24 years, all land was fixed for free. And where redistributions were carried out, the surplus of land, in excess of the male souls owed in cash, were paid but "the initial average redemption price", i.e. much cheaper than market prices.

These rules were aimed at encouraging the most prosperous peasants who had surplus allotment and leased land to leave the community as soon as possible.

Householders leaving the community had the right to demand that the land they were entitled to be allocated in one piece - cut(if a prominent courtyard remains in the village) or farm(if this courtyard moves the estate outside the village).

In this case, two goals were pursued:

- - to eliminate the striped land (when the allotments of one peasant household were in separate plots in different places) - one of the most important reasons for the backwardness of agricultural technology;

- - to disperse, to divide the peasant masses.

Explaining the political meaning of the dispersal of the peasant masses, P.A. every occasion ".

Considering that the land allocated to the yards leaving the community by one cut or farm in most cases infringed on the interests of the other community members (therefore, the communities could not agree to the allocation), the Decree of November 9 provided for the right to demand that a part of the communal land be strengthened in personal ownership, which must be satisfied by the community. within a month. If this is not done in due time, then the allocation of land can be formalized forcibly - by order of the zemstvo chief.

Not hoping to get the approval of the Decree of November 9, 1906 by the II State Duma, P.A.Stolypin designed its publication in the order of Art. 87 Basic laws without the Duma. And, indeed, the Decree received support only in the Third Duma, elected after the third June coup d'etat of 1907 under a new electoral law. Relying on the votes of the Right and Octobrists, the government finally achieved its approval on June 14, 1910 in the form of a law.

Moreover, the right-wing October majority of the Third Duma supplemented this law with a new section, which indicated that those communities in which no redistribution had been made since 1863 should be considered as having passed to the estate-courtyard hereditary land use. In other words, the law on June 14, 1910 forcibly dissolved the specified category of communities, regardless of the wishes of the peasants.

The subsequent law of May 29, 1911 took the final step towards equalizing the legal status of allotment and private land. Householders were recognized as legal owners of farms and cuts, as well as allotment land in forcibly disbanded communities, if the allotment land included at least a small part of the purchased land, i.e. heads of peasant households, and not the entire peasant household as a collective owner (as was the case earlier).

However, despite the strongest government pressure, the mass of the peasantry did not accept the reform.

In total, over the period from 1907 to 1916, a little more than 2 million peasant households left the communities. In addition, 468.8 thousand households in those communities in which there have been no redistributions since 1863 received deeds of ownership of their lands without their consent, i.e. by force. In total, about 2.5 million peasant households left the communities in this way.

As stated in the State Duma, one of the closest associates of A. A. Stolypin, the chief manager of land management and agriculture A. V. Krivoshein, the land should be in the hands of "the one who is best able to take from the land everything that it can give", and for this it is necessary to abandon the "unrealizable dream that everyone in the community can be well-fed and contented." In the redistribution of communal land, he saw a guarantee that "a broad general rise in agriculture is a matter of the near future."

Indeed, the main sellers of land turned out to be landless and horseless community members who left the community. Selling land, they went to work in the city or went to new lands (to Siberia, to the Far East, to Central Asia).

Although many peasants wanted to buy land, it turned out to be by no means an easy matter. The state did not have the money needed to carry out the reform (and this amount was determined at 500 million gold rubles). The amount actually allocated to finance the reform (issuing a state loan) was completely insufficient and, moreover, was plundered by officials and did not reach the peasants.

One could only hope for a loan from the Peasant Bank. A special decree, also adopted in November 1906, abolished the previously existing ban on pledging peasant allotments. The peasant bank was allowed to issue loans on the security of allotment land for the purchase of land when settling on farms and cuts, for improving agricultural technology (buying agricultural machinery), etc.

However, the Peasant Bank, buying up land at 45 rubles. per tithe (slightly more than a hectare), I sold them for 115–125 rubles. for a tithe, and a loan secured by land and for a relatively short period of time issued on enslaving terms. In case of non-payment of interest and regular payments to repay the debt on time, the bank took from the debtors and sold the mortgaged land. The money that went to buy land and pay interest on loans fell overhead on the price of agricultural products of peasant farms.

And yet, despite the high price and onerous conditions, some of the middle peasants and even the poor were buying land, denying themselves everything, trying to "break out into the people." The rich peasants also bought land, transforming their farms into commodity farms based on capitalist principles and hired labor.

But even more land was bought by persons, as they were then called, of the non-peasant class, who were not engaged in peasant labor, from among the rural and petty urban bourgeoisie, who had accumulated capital for themselves not by working on the land, but by other means; volost chiefs and scribes, wine shop owners, police officers, clergy, merchants, etc. This category bought up land for speculation (after all, the land was constantly becoming more expensive) and for leasing it to the same peasants, and the rent reached half of the harvest.

Since the practice of buying land for speculation and renting out became widespread, the government, alarmed by this phenomenon, issued a circular setting the standard for the purchase of allotment land for no more than 6 allotments within one county. However, in reality, many speculators and rentiers bought up (using the corruption of officials and bribes) 100-200 allotments.

An important element of the Stolypin reform was resettlement policy.

In September 1906, part of the land belonging to the royal family in Western Siberia, the Far East, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan was transferred for the resettlement of peasants from Central Russia. By resettling the peasants, the government tried to solve a number of problems:

- - defuse the agrarian overpopulation in the center of the country and, above all, in the Black Earth Region;

The broad peasant movement during the first Russian revolution forced tsarism to take urgent measures to resolve the agrarian question. In Russia at the beginning of the 20th century, two ways of solving the agrarian question were objectively possible, which corresponded to two different types of agrarian evolution along the bourgeois path. The first way of solving "from above" is "by preserving landlord ownership and the final destruction of the community, plundering it by fists", and the second way "from below" - "by destroying landlord ownership and nationalization of the entire land" (T. 17, -p. 124). The landowners, supported by the bourgeoisie, already in the course of the revolution decided decisively in favor of the first method, and the congress of the united nobility decided on the need to allow the peasants to leave the community freely and move freely to the outskirts. The peasantry opposed this measure and continued to fight for the elimination of landlord ownership, for the transfer of all the land to them. This aspiration of the peasant masses was reflected in the agrarian platform of the Trudoviks in the first two Dumas. The second method was more progressive, because it eliminated all the main vestiges of feudalism in Russia and cleared the way for the American path of bourgeois agrarian evolution, which was reflected in the development of kulak farms along the farm type. The Stolypin method was also objectively progressive, since it gave impetus to the development of capitalism along the Prussian path, but to an immeasurably lesser extent ensured the “free development of the productive forces” (T. 17. - P. 252).

The main content of the decree on November 9, 1906, approved by the Duma as law on June 13, 1910, was an attempt to direct capitalist development along the Prussian path. Seeing the inevitability of breaking the forms of land tenure, the autocracy outlined the radical destruction of peasant allotment land tenure, while the landlord was fully preserved. The Stolypin reform was by no means limited to the rout of the peasant community, as is often thought. The reform included a large complex of transformations, the main of which was the introduction of freedom to leave the community and resettlement to the outskirts. But simultaneously with the decree of November 9, 1906, several more important bills were enacted. Under the pressure of the revolution, tsarism took an extremely important measure, without which it was unthinkable to carry out all the others: on November 3, 1905, a year before the Stolypin law, the tsar's manifesto was published on the abolition of redemption payments for allotment lands. Thus, the form of land tenure changed, since allotment lands were only conditionally considered peasant property, since until their complete redemption, individual peasants (with household use) or the community (with communal use) could not sell these lands. Now the ransom was considered complete and the land was to be transferred to the full ownership of the courtyards or communities. Therefore, the question arose about the defeat of the communities. At the same time, the law on resettlement of 1904 was amended: the Regulation of the Council of Ministers of March 10, 19-06 was adopted, which radically changed this law, although it was called the Rules on the Application of the 1904 Law. "Restrictive rules on passports", introduced "freedom to choose a place of residence" for the peasants and promised a full equalization with other estates. At the same time, decrees were adopted on the allotment of part of the cabinet and specific lands for the resettlement of peasants, on new benefits for resettlement and on obtaining loans from the Peasant Bank for the purchase of land. Thus, appropriate preparation was carried out to ensure the exit from the community and the resettlement of immigrants (or rather, the majority of immigrants from among the poor and middle peasants) to the outskirts.

The meaning of the decree of November 9, 1906, like the law of June 14, 1910, was to replace communal property with courtyard ownership and courtyard land use (in non-communal areas) with the private property of the head of the courtyard, that is, personal private property. By 1906, there were 14.7 million peasant households in the villages and hamlets in Russia. Of these, 2.4 million households were already landless, and allotment lands had 12.3 million, including 9.5 million on communal law and 2.8 million on household law. There were no communities at all in the Baltic region of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus, partly there were no communities in the Left-Bank Ukraine, Eastern Belarus and Siberia. In these localities there was a courtyard use of land, and the decree introduced private land ownership here immediately (except for Siberia). If before 1906 there were only 752 thousand private landowners in Russia, now, in one fell swoop, 2.8 million landowners were added to them. The rest of the territory was dominated by the community, but to a large extent it was already decayed. Lenin noted that the decree on November 9, 1906 could not even have appeared, let alone carried out for several years, if the community itself had not disintegrated, had not singled out elements of the prosperous peasantry, which was interested in separation. The most decayed were those communities in which either there were no land redistributions at all, or they ceased in recent decades. That is why the State Duma in the law on June 14, 1910 singled out unlimited communities.

The decree on November 9, 1906 began to be prepared from May of this year, when the first congress of noble societies recommended that the government allow peasants to freely move to the outskirts, for which they also allow a free exit from the community. The draft decree was submitted by Stolypin to the Council of Ministers on October 1, 1906. When discussing it, some of the ministers expressed serious concerns that the adoption of the decree in accordance with Article 87 of the Basic Laws of the Russian Empire, that is, before the convocation of the Second Duma, would cause a resolute rebuff from many parties and the discontent of the peasants. But Stolypin and most of the ministers insisted on the adoption of the decree, and it was signed by the tsar on November 9 and was immediately published and began to be implemented. According to the existing legislation, the decree was submitted for approval by the II Duma, but there it met resolute resistance from the majority of the members of the commission on the agrarian question and criticism in the Duma itself, which was one of the main reasons for its dispersal in the III Duma. on the contrary, it was supported by the majority of the deputies and was detained for another reason. Many deputies in the agrarian commission insisted on Solea's radical solution to the problem of liquidating the community. After a lengthy debate, criticism of the draft law both from the left (Social Democrats, Trudoviks, non-party peasants) and from the right, it was approved. The law of June 14, 1910, as can be seen from comparing it with the text of the decree, facilitated the exit from the community and actually introduced the explicit liquidation of unrestricted communities.

The Stolypin agrarian reform was of progressive importance. It gave impetus to the development of wealthy kulak farms, which were able to buy allotments of poor people who left the community (the number of allotments purchased was limited, but it was easy to get by with the purchase of allotments for relatives and dummies). The kulaks received significant benefits for the purchase of cuts and farms through the Peasant Bank, they were allocated funds for agronomic assistance, etc. In the village, the class of prosperous peasantry was strengthened and expanded, which was distinguished by both a higher culture of agriculture, and higher yields, the use of machines, fertilizers ... At the expense of these farms, the overall average grain yield increased (from 39 to 43 poods per tenth), the harvest of marketable grain, and the number of machines (in value) in agriculture increased threefold. A cooperative boom began in the village, the growth of cooperatives of all types: credit, consumer, butter-making, flax-growing, agricultural artels, etc.

At the same time, the prospects of the second way of solving the agrarian question continued to be real, the struggle of the peasants for all the land, for the seizure of the landowners' latifundia grew. If the Stolypin reform was calculated on the victory of the Prussian path through the development of capitalist Junker farms and tying the prosperous peasantry to them, turning them into Grossbauers. then the peasant struggle against the Stolypinism was a struggle for a more progressive path of development of prosperous farms of the farm type, free from the tutelage of landowners. That is why, in the final analysis, the Stolypin reform had deep reactionary features. The reactionary nature of the Black Hundred program, Lenin wrote, consists ... in the development of capitalism according to the Junker type to strengthen the power and income of the landowner, to lay a new, more solid foundation for the building of autocracy ”(T. 16.- p. 351).

The agrarian issue is always the main one for Russia

Since 1906, the Russian government under the leadership of P.A. Stolypin carried out a set of measures in the field of agriculture. These activities are collectively called "Stolypin Agrarian Reform".

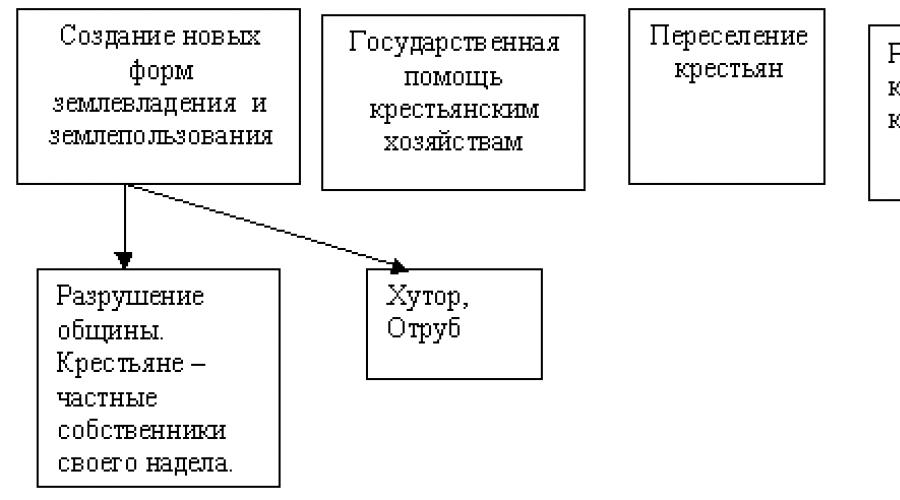

The main objectives of the reform:

- transfer of allotment land to the ownership of peasants;

- the gradual abolition of the rural community as a collective owner of land;

- extensive lending to peasants;

- purchase of landowners' land for resale to peasants on preferential terms;

- land management, which allows you to optimize the peasant economy by eliminating the striped area.

The reform set both short-term and long-term goals.

Short term: resolution of the "agrarian question" as a source of mass discontent (first of all, the cessation of agrarian unrest). Long term: sustainable prosperity and development of agriculture and the peasantry, the integration of the peasantry into a market economy.

The goals of the agrarian reform

The agrarian reform was aimed at improving peasant allotment land use and had little effect on private land tenure. It was held in 47 provinces of European Russia (all provinces, except for three provinces of the Ostsee Territory); Cossack land tenure and land tenure of the Bashkirs were not affected.

The historical need for reform

P.A. Stolypin (third from left) during his acquaintance with a farm near Moscow, October 1910

The idea of an agrarian reform arose as a result of the revolution of 1905-1907, when agrarian unrest intensified, and the activities of the first three State Dumas. The agrarian unrest reached a special scale in 1905, the government barely had time to suppress them. Stolypin at that time was the governor of the Saratov province, where the unrest was especially strong due to the poor harvest. In April 1906 P. A. Stolypin was appointed Minister of the Interior. The government project on the compulsory alienation of part of the landowners' lands was not adopted, the Duma was dissolved, and Stolypin was appointed chairman of the Council of Ministers. Due to the fact that the situation with the agrarian question remained uncertain, Stolypin decided to adopt all the necessary legal provisions, without waiting for the convocation of the Second Duma. On August 27, a decree was issued on the sale of state lands to peasants. On October 5, 1906, a decree was issued "On the abolition of certain restrictions on the rights of rural inhabitants and persons of other former taxable states" dedicated to improving the civil status of peasants. On October 14 and 15, decrees were issued expanding the activities of the Peasant Land Bank and facilitating the conditions for the purchase of land by peasants on credit. On November 9, 1906, the main legislative act of the reform was issued - the decree "On the addition of some provisions of the current law concerning peasant land tenure and land use", proclaiming the right of peasants to secure ownership of their allotment lands.

Thanks to Stolypin's bold step (the issuance of laws under Article 87. This article allowed the government to pass urgent laws without Duma approval in the interval between the dissolution of one Duma and the convocation of a new one), the reform became irreversible. The Second Duma expressed an even more negative attitude towards any undertakings by the government. It was disbanded after 102 days. There was no compromise between the Dumas and the government.

The Third Duma, without rejecting the government course, adopted all government bills for an extremely long time. As a result, since 1907, the government abandons active legislative activity in agrarian policy and proceeds to expand the activities of government institutions, increase the volume of distributed loans and subsidies. Since 1907, peasants' applications for securing land ownership have been met with long delays (there is not enough staff of land management commissions). Therefore, the main efforts of the government were aimed at training personnel (primarily land surveyors). But the funds allocated for the reform are also increasing, in the form of funding the Peasant Land Bank, subsidizing measures for agronomic assistance, and direct benefits to peasants.

Since 1910, the government course has changed somewhat - more attention is paid to supporting the cooperative movement.

Peasant life

On September 5, 1911, P.A.Stolypin was assassinated, and Minister of Finance V.N.Kokovtsov became prime minister. Kokovtsov, who showed less initiative than Stolypin, followed the intended course, without introducing anything new into the agrarian reform. The volume of land management work for the allocation of land, the amount of land assigned to the ownership of the peasants, the amount of land sold to the peasants through the Peasant Bank, the volume of loans to peasants grew steadily until the outbreak of the First World War.

During 1906-1911. decrees were issued, as a result of which the peasants were able to:

- take the allotment into property;

- freely leave the community and choose another place of residence;

- move to the Urals in order to get land (about 15 hectares) and money from the state to raise the economy;

- immigrants received tax breaks, were exempted from military service.

Agrarian reform

Have you achieved the goals of Stolypin's reform?

This is a rhetorical question when assessing the activities of reformers; it does not have a clear answer. Each generation will give its own answer.

Stolypin stopped the revolution and began deep reforms. At the same time, he fell victim to an assassination attempt, was unable to complete his reforms and did not achieve his main goal: create a great Russia in 20 peaceful years .

Nevertheless, during his activity, the following results have been achieved:

- The cooperative movement developed.

- The number of well-to-do peasants increased.

- In terms of gross grain harvest, Russia was in 1st place in the world.

- The number of livestock increased 2.5 times.

- About 2.5 million people moved to the new lands.