Biography of Dostoevsky's last years of life. Entries of the category "Dostoevsky Fyodor Mikhailovich

Read also

In 1821, a popular Russian writer, Fyodor Dostoevsky, was born. He spent his youth in a large noble family. His father was a rude and hot-tempered man. Everything in the house was adjusted to the father. In 1837, Dostoevsky's mother and Alexander Pushkin, who meant a lot to young Fyodor, suddenly passed away.

After that, Fyodor Dostoevsky begins to live in St. Petersburg. There he enters an engineering school. At that time it was considered one of the best educational institutions in Russia. This was also indicated by the fact that among Dostoevsky's classmates there were many talented people who became famous in the future. During his studies, he also read numerous works, including those of foreign authors. He preferred reading to the noisy society of his fellow students. This was one of his favorite activities. Many contemporaries were amazed at Fyodor Mikhailovich's readiness.

In 1844, Dostoevsky began his long career as a writer. One of his first serious creations was Poor People. This novel was well received by critics and brings fame to its creator. After 5 years, a turning point occurs in the life of the writer. He is sentenced to death, but at the last moment it is commuted to hard labor. The writer comprehends a lot in a new way.

Around 1860, Dostoevsky began writing a huge number of works. He published a two-volume collection of his writings. Contemporaries did not appreciate Dostoevsky's works, although modern critics praised his works.

Dostoevsky's texts literally stunned readers who had never personally encountered the horrors of hard labor.

In 1861. The Dostoevsky brothers set about creating their own magazine, which was named Vremya.

Dostoevsky died in 1881 from bronchitis and tuberculosis. The great writer left at the age of 59.

Option 2

On November 11, 1821, the great classic, writer and thinker Dostoevsky Fyodor Mikhailovich was born. From childhood, the future writer suffered from epilepsy. The family had 7 children, Fedor was born second, he had 3 brothers and 3 sisters. Mother Maria Feodorovna in 1837 dies of tuberculosis. After her death, his father sent his two children Fyodor and Mikhail to study at the St. Petersburg School with a military engineering profile. In 1839, his father dies.

From a young age, the future classic was interested in writing, constantly reading the works of Pushkin, Shakespeare, Lermontov, Schiller, Kornel, Gogol, Balzac, Gogol. In 1843 Fyodor Mikhailovich was so impressed by the work of "Eugene Grande" by O. Balzac that he undertook to translate it.

The years 1844-1845 are considered the beginning of the writer's career. The work "Poor People" is the very first work of the writer. After the publication of the novel, the writer gained fame and popularity. Belinsky V.G. and Nekrasov N.A. highly appreciated the work of the aspiring writer.

The second work of Fyodor Mikhailovich, work on which lasted from 1845 to 1846, is the story "The Double", which was severely criticized by many writers, as well as readers of a literary magazine. At the beginning of his career, all the writer's works were published only in the magazine of his brother.

The year 1849 becomes a crisis for the writer, he was sentenced to death by the court for participating in a circle with a revolutionary mood. Soon the punishment was replaced by hard labor for a period of 4 years in the Omsk fortress. After the end of the sentence, the writer is sent to military service as a soldier. After the events he experienced in penal servitude and during the service, the worldview of the young writer completely changed, he became more devout. While on duty, the writer meets Maria Isaeva, the wife of a former official, they have a romance. After the death of her husband, Maria married Fyodor Mikhailovich in 1857. Soon the young family moved to live in the city of St. Petersburg to work with their brother Mikhail in the magazines "Time" and "Epoch".

The year 1864 becomes very tragic for the classic, his wife and brother die. After these losses, Fyodor Mikhailovich begins to play roulette, accumulates numerous debts for himself. During this difficult period of his life, he worked on the novel Crime and Punishment, then on the novel The Gambler, for which he hired stenographer Anna Sinitkina, she soon became his wife.

The second wife, Anna, was 25 years younger than her husband. After the wedding, he instructed her to manage all his financial affairs. In marriage, they had 4 children. In 1869, the writer finishes working on the novel "The Idiot", in one of Prince Myshkin's monologues, previously experienced emotions before the death penalty are displayed. The period from 1871 to 1881 is considered the most fruitful for the writer's work, he writes works: "Demons", "Diary of a Writer", "Bobok", "Teenager", "The Dream of a Funny Man", "The Collapse of Baimakov's Office", "The Brothers Karamazov" and other.

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky is a great writer, classic of literature, philosopher, innovator, thinker, publicist, translator, representative of personalism and romanticism.

Born on 10/30/1821 in Moscow at the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor of the Moscow Orphanage. Father is a writer, mother Maria Nechaeva is the daughter of a merchant. Lived in the specified hospital.

The family had a patriarchal life, everything according to the will and routine of the father. The boy was raised by his nanny Alena Frolov, whom he loved and mentioned in the novel "Demons".

Parents from childhood taught the writer to literature. By the age of 10 he knew history, at the age of 4 he had already read it. Father put a lot of effort into Fedor's education.

1834 entered one of the best educational institutions in Moscow. At the age of 16 he moved to St. Petersburg to enter the Main Engineering School. During this period I decided to become a writer.

1843 becomes an engineer-second lieutenant, but soon resigns and goes to literature.

During his studies (1840-1842) he began his dramas "Maria Steward" and "Boris Godunov", in 1844 he finished the drama "Zhid Yankel" and at the same time translated foreign novels and wrote "Poor People". Thanks to his works, Dostoevsky becomes famous and well-known among other popular writers.

Deepens into different genres: the humorous "Novel in 9 Letters", the essay "The Petersburg Chronicles", the tragedies "Another's Wife" and "The Jealous Husband", the Christmas-tree poem "Fir-Trees and Wedding", the stories "Mistress", "Weak Heart" and many others ...

11/13/1849 sentenced to death for maintaining Belinsky's literature, then changed to 4 years and military service, while he survived a staged execution. In hard labor, he continued to secretly create his masterpieces.

1854 sent to the service, where he met Isaeva Maria Dmitrievna and married in 1957. In the same year he was pardoned.

The marriage with Isaeva lasted 7 years, there were no children. 4 children were born with his second wife Anna Grigorievna.

01/28/1881 died of pulmonary tuberculosis, chronic bronchitis. Buried in St. Petersburg.

Biography of Dostoevsky by dates and interesting facts

Fedor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky was born in 1821 in Moscow. In the family of the doctor of the clinic for the poor, Mikhail Andreevich, and later received the title of nobleman. Mother's name was Maria Fedorovna. They had six children. At the age of 16, Fedor and his older brother entered the preparatory boarding house in St. Petersburg.

At the end of 1843, he served as a pre-operator in the engineering team, and a year later he retired and devoted his time entirely to literature.

The first novel was written "Poor People" was published in 1845 and had significant success.

After Dostoevsky took part in an underground printing house. Arrested in 1849, all his archives were destroyed. Dostoevsky was awaiting execution, but Nicholas I changed the sentence to 4 years of hard labor.

In 1857, Fyodor married the widow Isaeva.

Has released comedy stories: "Uncle's Dream" and "The Village of Stepanchikovo and Its Residents."

1863, the dramatic novels The Gambler and The Idiot were published.

1864 his wife died.

In 1866 he worked on the love story "Crime and Punishment" and Dostoevsky's second wedding.

In the last years of his life, he was elected a Corresponding Member of the Academy of Sciences.

In 1878, Dostoevsky's beloved son died.

The last work "The Brothers Karamazov".

The famous writer died in early 1881.

Biography by dates and interesting facts. The most important thing.

Other biographies:

- Andrey Bogolyubsky

There is no data on the exact date of birth of Andrei Bogolyubsky. Researchers are inclined to believe that he was born in Suzdal in 1111. He was the son of Prince Yuri Dolgoruky. Was educated, like all princely

- William Harvey

The great scientist was born on April 1, 1578 in the small county of Kent. Originally from a wealthy merchant family.

- Andreas Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius (1514 - 1564) - the founder of modern medical science - anatomy. Court physician of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, a contemporary of the famous Swiss scientist Paracelsus, a representative of the Whiting dynasty of medicine.

- Louis Armstrong

Louis Armstrong is the most famous representative of the jazz musical direction. He is known for his songs, masterful trumpet playing and charm. Many people still prefer classical jazz in his performance.

- Claude Debussy

Debussy is a great French composer, critic, conductor, pianist and founder of Musical Impressionism. Ashile Claude Debussy was born in a small town in 1862

Someone calls him a prophet, a gloomy philosopher, someone - an evil genius. He himself called himself "a child of the century, a child of unbelief, doubt." Much has been said about Dostoevsky as a writer, but his personality is surrounded by an aura of mystery. The multifaceted nature of the classic allowed him to leave a mark on the pages of history, to inspire millions of people around the world. His ability to expose vices, without turning away from them, made the heroes so alive, and the works - full of mental suffering. Immersion in the world of Dostoevsky can be painful, difficult, but it gives rise to something new in people, this is exactly the literature that educates. Dostoevsky is a phenomenon that needs to be studied for a long time and thoughtfully. A short biography of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, some interesting facts from his life, work will be presented to your attention in the article.

Brief biography in dates

The main task of life, as Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky wrote, is “not to lose heart, not to fall,” in spite of all the trials sent from above. And a lot of them fell to his lot.

November 11, 1821 - birth. Where was Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky born? He was born in our glorious capital - Moscow. Father - head physician Mikhail Andreevich, a religious, pious family. Called by the name of his grandfather.

The boy began to study at a young age under the guidance of his parents, by the age of 10 he knew the history of Russia quite well, his mother taught to read. Attention was also paid to religious education: daily prayer before bedtime was a family tradition.

In 1837, the mother of Fyodor Mikhailovich, Maria, dies, in 1839, father Mikhail.

1838 - Dostoevsky entered the Main Engineering School of St. Petersburg.

1841 - becomes an officer.

1843 - Enrolled in the Engineering Corps. Studying was not pleasing, there was a strong craving for literature, the writer did his first creative experiments even then.

1847 - visiting Petrashevsky Fridays.

April 23, 1849 - Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress.

From January 1850 to February 1854 - the Omsk fortress, hard labor. This period had a strong influence on the writer's creativity and attitude.

1854-1859th - the period of military service, the city of Semipalatinsk.

1857th - a wedding with Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva.

June 7, 1862 - the first trip abroad, where Dostoevsky stays until October. I got carried away with gambling for a long time.

1863 - falling in love, relations with A. Suslova.

1864 - the writer's wife Maria, elder brother Mikhail die.

1867 - marries stenographer A. Snitkina.

Until 1871 they traveled a lot outside of Russia.

1877 - spends a lot of time with Nekrasov, then gives a speech at his funeral.

1881 - Dostoevsky Fyodor Mikhailovich dies, he was 59 years old.

Biography in detail

The childhood of the writer Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky can be called prosperous: born into a noble family in 1821, he received an excellent education at home and upbringing. Parents managed to instill a love for languages (Latin, French, German), history. After reaching the age of 16, Fedor was sent to a private boarding school. Then the training continued at the military engineering school of St. Petersburg. Dostoevsky showed interest in literature even then, visited literary salons with his brother, tried to write himself.

As the biography of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky testifies, 1839 takes the life of his father. Internal protest is looking for a way out, Dostoevsky begins to get acquainted with the socialists, attends Petrashevsky's circle. The novel "Poor People" was written under the influence of the ideas of that period. This work allowed the writer to finally finish the hated engineering service and take up literature. From an unknown student, Dostoevsky became a successful writer until the censorship intervened.

In 1849, the ideas of the Petrashevists were recognized as harmful, the members of the circle were arrested and sent to hard labor. It is noteworthy that the sentence was originally a death sentence, but the last 10 minutes changed it. The Petrashevites who were already standing on the scaffold were pardoned, limiting the punishment to four years of hard labor. Mikhail Petrashevsky was sentenced to life in prison. Dostoevsky was sent to Omsk.

The biography of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky says that serving a sentence was given to a writer hard. He compares that time to being buried alive. Heavy monotonous work like burning bricks, disgusting conditions, cold undermined Fyodor Mikhailovich's health, but also gave him food for thought, new ideas, themes for creativity.

After serving his sentence, Dostoevsky serves in Semipalatinsk, where the only joy was the first love - Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva. These relationships were tender, somewhat reminiscent of the relationship between mother and son. Stopped the writer from making a proposal to a woman, only the presence of her husband. He died a little later. In 1857, Dostoevsky finally achieves Maria Isaeva, they get married. After the marriage, the relationship changed somewhat, the writer himself speaks of them as "unfortunate".

1859 - return to St. Petersburg. Dostoevsky writes again, opens the Vremya magazine with his brother. Brother Mikhail does business clumsily, gets into debt, dies. Fyodor Mikhailovich has to deal with debts. He has to write quickly in order to be able to pay all the accumulated debts. But even in such a hurry, the most complex works of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky were created.

In 1860, Dostoevsky falls in love with the young Apollinaria Suslova, who is not at all like his wife Maria. The relationship was also different - passionate, bright, lasted three years. At the same time, Fedor Mikhailovich is fond of playing roulette, he loses a lot. This period of his life is reflected in the novel The Gambler.

1864 claimed the lives of his brother and wife. In the writer Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, something seems to have broken. Relations with Suslova are coming to naught, the writer feels lost, alone in the world. He tries to run away from himself abroad, to distract himself, but melancholy does not leave. Epileptic seizures are becoming more frequent. This is how Anna Snitkina, a young stenographer, recognized and fell in love with Dostoevsky. The man shared his life story with the girl, he needed to speak out. Gradually, they became closer, although the age difference was 24 years. Anna accepted Dostoevsky's offer to marry him sincerely, because Fyodor Mikhailovich evoked the brightest, enthusiastic feelings in her. The marriage was perceived negatively by society, Dostoevsky's adopted son Pavel. The newlyweds leave for Germany.

The relationship with Snitkina had a beneficial effect on the writer: he got rid of his addiction to roulette, became calmer. In 1868 Sophia is born, but dies three months later. After a difficult period of common experiences, Anna and Fyodor Mikhailovich continue to try to conceive a child. They succeed: Love (1869), Fedor (1871) and Alexei (1875) are born. Alexey inherited the disease from his father, died at the age of three. The wife became for Fyodor Mikhailovich support and support, a spiritual outlet. In addition, she helped improve the financial situation. The family moves to Staraya Russa to escape from the nervous life in St. Petersburg. Thanks to Anna, a wise girl beyond her years, Fyodor Mikhailovich becomes happy, at least for a short while. Here they spend their time happily and serenely until Dostoevsky's health forces them to return to the capital.

In 1881, the writer dies.

Carrot or stick: how Fedor Mikhailovich raised children

The indisputability of the father's authority was the basis of Dostoevsky's upbringing, which also passed on to his own family. Decency, responsibility - these qualities the writer managed to put into his children. Even if they did not grow up as geniuses like their father, a certain craving for literature existed in each of them.

The writer considered the main mistakes of education:

- ignoring the inner world of the child;

- intrusive attention;

- bias.

He called a crime against a child suppression of individuality, cruelty, making life easier. Dostoevsky believed that the main instrument of education was not corporal punishment, but parental love. He himself incredibly loved his children, greatly worried about their illnesses and losses.

An important place in the life of a child, as Fyodor Mikhailovich believed, should be given to spiritual light, religion. The writer rightly believed that a child always takes an example from the family where he was born. Dostoevsky's educational measures were based on intuition.

Literary evenings were a good tradition in the family of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. These evening readings of masterpieces of literature were traditional in the childhood of the author himself. Often the children of Dostoevsky Fyodor Mikhailovich fell asleep, did not understand anything they read, but he continued to educate literary taste. Often the writer read with such a feeling that in the process he began to cry. He loved to hear what impression this or that novel made on children.

Another educational element is a visit to the theater. Opera was preferred.

Lyubov Dostoevskaya

Attempts to become a writer were unsuccessful with Lyubov Fedorovna. Maybe the reason was that her work was always inevitably compared with her father's brilliant novels, maybe she was writing about the wrong one. As a result, the main work of her life was the description of her father's biography.

The girl who lost him at the age of 11 was very afraid that the sins of Fyodor Mikhailovich would not be forgiven in the next world. She believed that after death, life continues, but here, on earth, one must seek happiness. For Dostoevsky's daughter, it was primarily in a clear conscience.

Lyubov Fedorovna lived to be 56 years old, spent the last few years in sunny Italy. She was probably happier there than at home.

Fedor Dostoevsky

Fedor Fedorovich became a horse breeder. The boy began to show interest in horses as a child. I tried to create literary works, but it didn't work out. He was vain, strived to achieve success in life, these qualities were inherited from his grandfather. Fedor Fedorovich, if he was not sure that he could be the first in something, preferred not to do it, his pride was so expressed. He was nervous and withdrawn, wasteful, inclined to excitement, like his father.

Lost his father Fedor at the age of 9, but he managed to put the best qualities in him. The upbringing of his father helped him a lot in life, he received a good education. In his business, he achieved great success, perhaps because he loved what he was doing.

Creative way in dates

The beginning of Dostoevsky's career was bright, he wrote in many genres.

The genres of the early period of creativity of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky:

- humorous story;

- physiological outline;

- tragicomic story;

- Christmas story;

- story;

- novel.

In 1840-1841 - the creation of the historical dramas "Mary Stuart", "Boris Godunov".

1844 - Balzac's translation of Eugenia Grande is published.

1845 - finished the story "Poor People", met with Belinsky, Nekrasov.

1846 - "Petersburg Collection" was published, "Poor People" were published.

In February "Double" was published, in October - "Mister Prokharchin".

In 1847, Dostoevsky wrote "The Hostess", published in the "St. Petersburg Vedomosti".

In December 1848, White Nights was written, in 1849 - Netochka Nezvanova.

1854-1859th - service in Semipalatinsk, "Uncle's Dream", "Stepanchikovo Village and Its Inhabitants."

In 1860, a fragment of the "Notes of a Dead House" was published in the "Russian World". The first collected works have been published.

1861 - the beginning of the publication of the magazine "Time", the printing of a part of the novel "The Humiliated and the Insulted", "Notes from the House of the Dead".

In 1863, "Winter Notes on Summer Impressions" was created.

May of the same year - the Vremya magazine was closed.

1864 - the beginning of the publication of the "Epoch" magazine. "Notes from the Underground".

1865th - "An Unusual Event, or Passage in the Passage" is printed in "Crocodile".

1866 - written by Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky "Crime and Punishment", "The Gambler". Departure abroad with family. "Moron".

In 1870, Dostoevsky wrote the story "The Eternal Husband".

1871-1872 - "Demons".

1875th - Printing of "Teenager" in "Notes of the Fatherland".

1876 - the resumption of the activities of the "Writer's Diary".

From 1879 to 1880, The Brothers Karamazov was written.

Places in St. Petersburg

The city keeps the spirit of the writer, many of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky's books were written here.

- Dostoevsky studied at the Engineering Mikhailovsky Castle.

- The Serapinskaya hotel on Moskovsky Prospekt became the writer's place of residence in 1837, where he lived when he saw St. Petersburg for the first time in his life.

- Poor People was written in the house of the post-director Pryanichnikov.

- "Mr. Prokharchin" was created in the Kochenderfer house on Kazanskaya Street.

- Fyodor Mikhailovich lived in Soloshich's apartment building on Vasilievsky Island in the 1840s.

- Kotomin's apartment building introduced Dostoevsky to Petrashevsky.

- The writer lived on Voznesensky Prospect during his arrest, wrote "White Nights", "Honest Thief" and other stories.

- "Notes from the House of the Dead", "Humiliated and Insulted" were written on 3rd Krasnoarmeyskaya Street.

- The writer lived in the house of A. Astafyeva in 1861-1863.

- In the Strubinsky house on Grechesky Prospekt - from 1875 to 1878.

Dostoevsky's symbolism

You can endlessly analyze the books of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, finding new and new symbols. Dostoevsky mastered the art of penetrating into the essence of things, their soul. It is thanks to the ability to unravel these symbols one by one that the journey through the pages of the novels becomes so fascinating.

- Axe.

This symbol carries a deadly meaning, being a kind of emblem of Dostoevsky's work. The ax symbolizes murder, crime, a decisive desperate step, a turning point. If a person utters the word "ax", most likely, the first thing that comes to his mind is "Crime and Punishment" by Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky.

- Clean linen.

Its appearance in novels occurs at certain similar moments, which allows us to speak of symbolism. For example, a maid hanging out clean linen prevented Raskolnikov from committing murder. Ivan Karamazov had a similar situation. It is not so much the linen itself that is symbolic, but its color - white, denoting purity, correctness, and purity.

- Smells.

It is enough to skim through any of Dostoevsky's novels to understand how important smells are to him. One of them, which occurs more often than others, is the smell of a pernicious spirit.

- Silver pledge.

One of the most important symbols. The silver cigarette case was not made of silver at all. The motive of falsity, falsity, suspicion appears. Raskolnikov, having made a cigarette box out of wood, similar to a silver one, as if he had already committed a deception, a crime.

- The ringing of a brass bell.

The symbol plays a warning role. A small detail makes the reader feel the mood of the hero, present the events more vividly. Small objects are endowed with strange, unusual features, emphasizing the exclusivity of circumstances.

- Wood and iron.

In novels, there are many things from these materials, each of them carries a certain meaning. If a tree symbolizes a person, a sacrifice, bodily torment, then iron is a crime, murder, evil.

Finally, I would like to note some interesting facts from the life of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky.

- Dostoevsky wrote most of all in the last 10 years of his life.

- Dostoevsky loved sex, used the services of prostitutes, even when he was married.

- Nietzsche called Dostoevsky the best psychologist.

- He smoked a lot, loved strong tea.

- He was jealous of his women to every pillar, forbidden even to smile in public.

- He worked more often at night.

- The hero of the novel "The Idiot" is a self-portrait of the writer.

- There are many film adaptations of Dostoevsky's works, as well as those dedicated to him.

- The first child appeared at Fyodor Mikhailovich at the age of 46.

- Leonardo DiCaprio also celebrates his birthday on November 11th.

- More than 30,000 people attended the writer's funeral.

- Sigmund Freud considered Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov the greatest ever written.

We also present to your attention the famous quotes of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky:

- One must love life more than the meaning of life.

- Freedom is not about not holding yourself back, but about being in control of yourself.

- In everything there is a line beyond which it is dangerous to cross; for once stepping over it is impossible to turn back.

- Happiness is not in happiness, but only in achieving it.

- No one will take the first step, because everyone thinks that it is not mutual.

- The Russian people seem to enjoy their suffering.

- Life goes breathless without an aim.

- To stop reading books is to stop thinking.

- There is no happiness in comfort; happiness is bought by suffering.

- In a truly loving heart, either jealousy kills love, or love kills jealousy.

Conclusion

The result of each person's life is his deeds. Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (years of his life - 1821-1881) left behind great novels, having lived a relatively short life. Who knows if these novels would have been born if the author's life had been easy, without obstacles and hardships? Dostoevsky, who is known and loved, is impossible without suffering, emotional throwing, inner overcoming. It is they who make the works so real.

It always seems strange to me that even a great writer like Dostoevsky (1821-1881), and almost could not imagine what would happen in very recent times. Although he wrote "Demons", a pamphlet on the Russian revolutionaries, he could not foresee that the danger would come from a somewhat different direction and that almost everything was ready for the coming of this danger. The "conspiracy" (in which no one believes) has already been drawn up, and only some technical questions of its implementation remained.

Dostoevsky, who idolized the common Russian people, "fervently prayed" for the sovereign and for the Russian empire, hated the Western peoples and predicted their imminent death - how much malice they expressed about the Germans, French, Swiss, not to mention the Poles! - did not foresee that his beloved wife and children would live to see the greatest Russian catastrophe, fall into the dumbest Soviet land.

In 1879, he wrote to Anna Grigorievna, his wife, about the purchase of the estate:

“I’m all, my dear, thinking about my death myself (seriously thinking) and about what I’ll leave you and the children with. ... you do not like villages, but I have all the convictions that 1) the village is capital, which will triple by the age of the children, and 2) that the one who owns the land also participates in political power over the state. This is the future of our children ... "

"I am in awe of the children and their fate"

Kramskoy. Portrait of Dostoevsky.

I already wrote earlier that the writer's wife, Anna Grigorievna, lived until 1918. In April 1917, she decided to retire to her small estate near Adler to wait for the riots to calm down. But the revolutionary storm reached the Black Sea coast as well. A former gardener at the Dostoevskaya estate, who had deserted from the front, declared that he, the proletarian, should be the real owner of the estate. A.G. Dostoevskaya fled to Yalta. In the Yalta hell of 1918, when the city passed from hand to hand, she spent the last months of her life. There was even no one to bury her until six months later, Fyodor Fyodorovich Dostoevsky's son arrived from Moscow:

“At the height of the Civil War, Fyodor Dostoevsky Jr. made his way to the Crimea, but he didn’t find his mother alive. She was kicked out of her dacha by the caretaker, and she died abandoned by everyone in a Yalta hotel. According to the recollections of his son (grandson of the writer) Andrei Fyodorovich Dostoevsky, when Fyodor Fyodorovich took out Dostoevsky's archive from the Crimea to Moscow, which remained after the death of Anna Grigorievna, he was almost shot by the Chekists on suspicion of speculation, they thought they were transporting contraband in baskets. "

Dostoevsky's children were not marked by any significant talents, and they did not live long.

Dostoevsky's son, Fedor (1871 - 1921), graduated from two faculties of the University of Dorpat - legal and natural, became a specialist in horse breeding. He was proud and vain, strived to be the first everywhere. He tried to prove himself in the literary field, but was disappointed in his abilities. Lived and died in Simferopol. The grave has not survived.

Darling Dostoevsky's daughter Lyubov, Lyubochka (1868-1926), according to the recollections of contemporaries, “she was arrogant, arrogant, and simply quarrelsome. She did not help her mother to perpetuate the glory of Dostoevsky, creating her image as the daughter of the famous writer, later she left Anna Grigorievna altogether. " In 1913, after another trip abroad for treatment, she remained there forever (abroad she became "Emma"). She wrote an unsuccessful book "Dostoevsky in the memoirs of his daughter" ... Her personal life did not work out. She died in 1926 from leukemia in the Italian city of Bolzano.

Dostoevsky's nephew, the son of his younger brother, Andrei Andreevich (1863-1933), amazingly modest and devoted to the memory of Fyodor Mikhailovich. He had a luxurious apartment on Pochtamtskaya. Of course, after the revolution, it was overhauled. Andrei Andreevich was sixty-six when he sent to the White Sea Canal. Six months after his release, he died ...

The former Dostoevskys' apartment was partitioned off and converted into Soviet communal apartment, and the family was squeezed into one room ... And before the centenary of Lenin, this house was declared unfit for habitation and made his great-grandson a housewarming party on the outskirts of Leningrad, in a squalid Khrushchev building.

Dostoevsky's great-grandson himself, Dmitry Andreevich, Born in 1945, lives in St. Petersburg. He is a tram driver by profession, and has worked on route 34 all his life.

Great-grandson Dmitry Dostoevsky

(October 30 (November 11) 1821, Moscow, Russian Empire - January 28 (February 9) 1881, St. Petersburg, Russian Empire)

ru.wikipedia.org

Biography

life and creation

The writer's youth

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky was born on October 30 (November 11), 1821 in Moscow. Father, Mikhail Andreevich, from the clergy, received the title of nobility in 1828, worked as a doctor in the Moscow Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor on Novaya Bozhedomka (now - Dostoevsky Street). Having acquired a small estate in the Tula province in 1831-1832, he cruelly treated the peasants. Mother, Maria Fedorovna (nee Nechaev), came from a merchant family. Fedor was the second of 7 children. According to one of the assumptions, Dostoevsky comes from the paternal line of the Pinsk gentry, whose family estate Dostoevo in the 16th-17th centuries was located in the Belarusian Polesie (now the Ivanovsky district of the Brest region, Belarus). On October 6, 1506, Danila Ivanovich Rtishchev received this estate from Prince Fyodor Ivanovich Yaroslavich for his services. From that time on, Rtishchev and his heirs began to be called Dostoevsky.

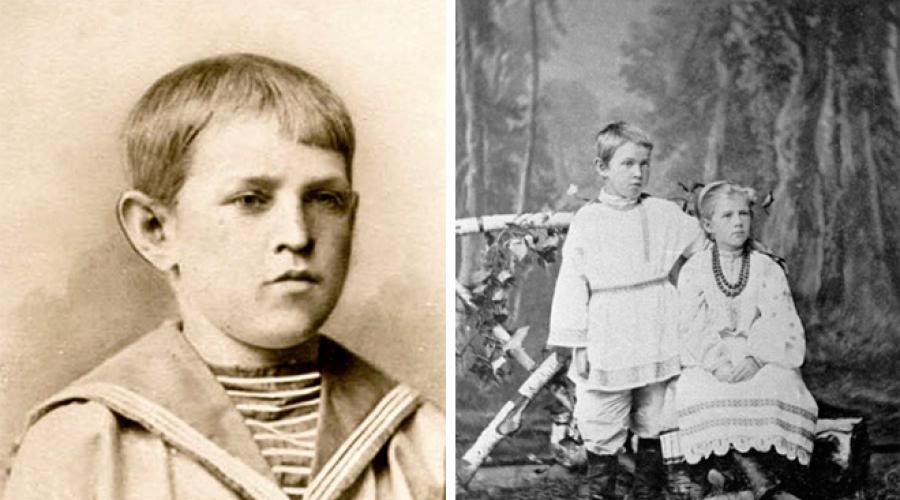

When Dostoevsky was 15 years old, his mother died of consumption, and his father sent his eldest sons, Fyodor and Mikhail (who later also became a writer), to KF Kostomarov's boarding school in St. Petersburg.

1837 was an important date for Dostoevsky. This is the year of the death of his mother, the year of the death of Pushkin, whose work he (like his brother) is read from childhood, the year of moving to St. Petersburg and entering the military engineering school, now the Military Engineering and Technical University. In 1839 he receives news of the murder of his father by serfs. Dostoevsky takes part in the work of Belinsky's circle. A year before his discharge from military service, Dostoevsky for the first time translated and published Balzac's Eugene Grande (1843). A year later, his first work, Poor People, was published, and he immediately became famous: V. G. Belinsky highly appreciated this work. But the next book, The Double, runs into a misunderstanding.

Soon after the publication of White Nights, the writer was arrested (1849) in connection with the Petrashevsky case. Although Dostoevsky denied the charges against him, the court recognized him as "one of the most important criminals."

The military court finds the defendant Dostoevsky guilty of the fact that, having received in March this year from Moscow from the nobleman Pleshcheev ... a copy of the criminal letter of the writer Belinsky, he read this letter in the meetings: first from the accused Durov, then from the accused Petrashevsky. That is why the military court sentenced him for failure to report on the spread of the criminal about religion and the government of the letter of the writer Belinsky ... to deprive him on the basis of the Code of military decrees ... of ranks and all rights of the state and subject to the death penalty by shooting ..

The trial and the harsh death sentence (December 22, 1849) on the Semyonovsky parade ground was framed as a mock execution. At the last moment, the convicts were pardoned and sentenced to hard labor. One of those sentenced to death, Grigoriev, went mad. The feelings that he might have experienced before the execution, Dostoevsky conveyed in the words of Prince Myshkin in one of the monologues in the novel The Idiot.

During a short stay in Tobolsk on the way to the place of hard labor (January 11-20, 1850), the writer met with the wives of the exiled Decembrists: Zh. A. Muravyova, P. Ye. Annenkova and ND Fonvizina. The women gave him the Gospel, which the writer kept all his life.

Dostoevsky spent the next four years in hard labor in Omsk. In 1854, when the four years to which Dostoevsky was sentenced had expired, he was released from hard labor and sent as a private to the 7th Siberian Line Battalion. During his service in Semipalatinsk, he became friends with Chokan Valikhanov, the future famous Kazakh traveler and ethnographer. A common monument was erected there to the young writer and young scientist. Here he began an affair with Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva, who was married to a high school teacher Alexander Isaev, a bitter drunkard. After some time, Isaev was transferred to the place of the assessor in Kuznetsk. On August 14, 1855, Fyodor Mikhailovich receives a letter from Kuznetsk: M.D. Isaeva's husband died after a long illness.

On February 18, 1855, Emperor Nicholas I dies. Dostoevsky writes a loyal poem dedicated to his widow, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, and as a result becomes a non-commissioned officer: on October 20, 1856 Fyodor Mikhailovich was promoted to ensign. On February 6, 1857, Dostoevsky was married to Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva in the Russian Orthodox Church in Kuznetsk.

Immediately after the wedding, they leave for Semipalatinsk, but on the way, Dostoevsky has an epileptic seizure, and they stop for four days in Barnaul.

On February 20, 1857, Dostoevsky and his wife returned to Semipalatinsk. The period of imprisonment and military service was a turning point in the life of Dostoevsky: from a still undecided in life "seeker of truth in man" he turned into a deeply religious person, whose only ideal for his entire subsequent life was Christ.

In 1859, in Otechestvennye zapiski, Dostoevsky published his stories The Village of Stepanchikovo and Its Inhabitants and Uncle's Dream.

On June 30, 1859, Dostoevsky was issued a temporary ticket number 2030, allowing him to travel to Tver, and on July 2, the writer left Semipalatinsk. In 1860, Dostoevsky returned to St. Petersburg with his wife and adopted son Pavel, but unofficial surveillance of him did not stop until the mid-1870s. From the beginning of 1861 Fyodor Mikhailovich helped his brother Mikhail to publish his own magazine "Time", after the closure of which in 1863 the brothers began to publish the magazine "Epoch". Such works of Dostoevsky appear on the pages of these magazines, such as "The Humiliated and Insulted", "Notes from the House of the Dead", "Winter Notes on Summer Impressions" and "Notes from the Underground".

Dostoevsky undertakes a trip abroad with the young emancipated special Apollinaria Suslova, in Baden-Baden he is fond of the ruinous game of roulette, feels a constant need for money and at the same time (1864) loses his wife and brother. The unusual way of European life completes the destruction of the socialist illusions of youth, forms a critical perception of bourgeois values and rejection of the West.

Six months after the death of his brother, the publication of "Epoch" ceases (February 1865). In a desperate financial situation, Dostoevsky writes the chapters of Crime and Punishment, sending them to MN Katkov directly into the magazine set of the conservative Russian Bulletin, where they are printed from issue to issue. At the same time, under the threat of losing the rights to his publications for 9 years in favor of the publisher FT Stellovsky, he undertook to write him a novel, for which he did not have enough physical strength. On the advice of friends, Dostoevsky hires a young stenographer, Anna Snitkina, who helps him cope with this task.

The novel "Crime and Punishment" was finished and paid very well, but so that the creditors would not take this money away from him, the writer went abroad with his new wife, Anna Grigorievna Snitkina. The trip is reflected in the diary that A.G. Snitkina-Dostoevskaya began to keep in 1867. On the way to Germany, the couple stopped for several days in Vilna.

The flowering of creativity

Snitkina arranged the life of the writer, took over all the economic issues of his activities, and since 1871 Dostoevsky gave up the roulette wheel forever.

In October 1866, in twenty-one days he wrote and on the 25th completed the novel "The Gambler" for FT Stellovsky.

For the last 8 years, the writer has lived in the town of Staraya Russa, Novgorod province. These years of life were very fruitful: 1872 - "Demons", 1873 - the beginning of the "Diary of a Writer" (a series of feuilletons, essays, polemical notes and passionate journalistic notes on the topic of the day), 1875 - "Teenager", 1876 - "Meek", 1879 -1880 - The Brothers Karamazov. At the same time, two events became significant for Dostoevsky. In 1878, Emperor Alexander II invited the writer to his place to introduce him to his family, and in 1880, just a year before his death, Dostoevsky made a famous speech at the opening of the monument to Pushkin in Moscow. During these years, the writer became close to conservative journalists, publicists and thinkers, corresponded with the prominent statesman K.P. Pobedonostsev.

Despite the fame that Dostoevsky gained at the end of his life, truly enduring, worldwide fame came to him after his death. In particular, Friedrich Nietzsche admitted that Dostoevsky was the only psychologist from whom he could learn a thing or two ("Twilight of the Idols").

On January 26 (February 9), 1881, Dostoevsky's sister Vera Mikhailovna came to the Dostoevsky's house to ask her brother to give up his share of the Ryazan estate, inherited from his aunt A.F. Kumanina, in favor of the sisters. According to the story of Lyubov Fedorovna Dostoevskaya, there was a stormy scene with explanations and tears, after which Dostoevsky's throat began to bleed. Perhaps this unpleasant conversation was the first impetus to the aggravation of his illness (emphysema) - two days later the great writer died.

Buried at the Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg.

Family and environment

The writer's grandfather Andrei Grigorievich Dostoevsky (1756 - circa 1819) served as a Uniate priest, later as an Orthodox priest in the village of Voytovtsy near Nemirov (now the Vinnytsia region of Ukraine).

Father, Mikhail Andreevich (1787-1839), studied at the Moscow branch of the Imperial Medical and Surgical Academy, served as a doctor in the Borodino infantry regiment, an intern at the Moscow military hospital, a doctor at the Mariinsky hospital of the Moscow orphanage (that is, in a hospital for the poor, still known called Bozhedomki). In 1831 he acquired the small village of Darovoe in the Kashirsky district of the Tula province, and in 1833 the neighboring village of Cheremoshnya (Chermashnya), where in 1839 he was killed by his own serfs:

His addiction to alcoholic beverages apparently increased, and he was almost constantly in an abnormal position. Spring came, promising little good ... It was at that time in the village of Chermashne, in the fields under the edge of the forest, an artel of peasants, of a dozen or a half dozen people worked; the case, then, was away from home. Pissed off from himself by some unsuccessful action of the peasants, or perhaps only what seemed to him as such, his father flared up and began to shout at the peasants very much. One of them, the more daring, responded to this cry with strong rudeness and after that, fearing this rudeness, shouted: "Guys, karachun to him! ..". And with this cry, all the peasants, up to 15 people, rushed at their father and in an instant, of course, finished with him ... - From the memoirs of A. M. Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky's mother, Maria Feodorovna (1800-1837), came from a wealthy Moscow merchant family of the Nechaevs, which after the Patriotic War of 1812 lost most of their fortune. At the age of 19, she married Mikhail Dostoevsky. She was, according to the recollections of the children, a kind mother and gave birth to four sons and four daughters in marriage (son Fedor was the second child). MF Dostoevskaya died of consumption. According to researchers of the great writer, certain features of Maria Feodorovna were reflected in the images of Sofia Andreevna Dolgoruka ("Teenager") and Sofia Ivanovna Karamazova ("The Brothers Karamazov") [source not specified 604 days].

Dostoevsky's elder brother Mikhail also became a writer, his work was marked by the influence of his brother, and work on the magazine "Time" was carried out by the brothers to a large extent jointly. The younger brother Andrei became an architect, Dostoevsky saw in his family a worthy example of family life. A. M. Dostoevsky left valuable memories of his brother. Of the Dostoevsky sisters, the closest relationship was established between the writer and Varvara Mikhailovna (1822-1893), about whom he wrote to his brother Andrei: “I love her; she is a glorious sister and a wonderful person ... ”(November 28, 1880). Of the numerous nephews and nieces, Dostoevsky loved and singled out Maria Mikhailovna (1844-1888), whom, according to the memoirs of L.F. her success with young people ”, however, after the death of Mikhail Dostoevsky, this closeness faded away.

Fyodor Mikhailovich's descendants continue to live in St. Petersburg.

Philosophy

As OM Nogovitsyn showed in his work, Dostoevsky is the most prominent representative of "ontological", "reflexive" poetics, which, unlike traditional, descriptive poetics, leaves the character in a sense free in his relationship with the text that describes him ( that is, the world for him), which is manifested in the fact that he is aware of his relationship with him and acts on the basis of it. Hence all the paradox, contradiction and inconsistency of Dostoevsky's characters. If in traditional poetics the character remains always in the power of the author, is always captured by the events happening to him (captured by the text), that is, it remains completely descriptive, completely included in the text, completely understandable, subordinate to causes and consequences, the movement of the narrative, then in ontological poetics we are for the first time we encounter a character who is trying to resist the textual elements, his subservience to the text, trying to "rewrite" it. With this approach, writing is not a description of the character in various situations and his positions in the world, but empathy for his tragedy - his willful unwillingness to accept the text (world), in its inescapable redundancy in relation to it, potential infinity. For the first time, M.M. Bakhtin drew attention to such a special attitude of Dostoevsky to his characters.

Political views

During Dostoevsky's life, at least two political currents were in conflict in the cultural strata of society - Slavophilism and Westernism, the essence of which is approximately as follows: the adherents of the first argued that the future of Russia in nationality, Orthodoxy and autocracy, the adherents of the second believed that Russians should take an example in everything Europeans. Both those and others reflected on the historical fate of Russia. Dostoevsky, however, had his own idea - "soil cultivation". He was and remained a Russian person, inextricably linked with the people, but at the same time did not deny the achievements of the culture and civilization of the West. Over time, Dostoevsky's views developed, and during his third stay abroad, he finally became a convinced monarchist.

Dostoevsky and the "Jewish question"

Dostoevsky's views on the role of Jews in Russian life were reflected in the writer's journalism. For example, discussing the further fate of the peasants freed from serfdom, he writes in the Writer's Diary for 1873:

“It will be so if the work continues, if the people themselves do not come to their senses; and the intelligentsia will not help him. If he doesn’t come to his senses, then the whole, entirely, in the shortest possible time will be in the hands of all kinds of Jews, and here no community will save him ... , therefore, they will have to be supported. "

The Electronic Jewish Encyclopedia claims that anti-Semitism was an integral part of Dostoevsky's worldview and found expression both in novels and stories, and in the writer's journalism. A clear confirmation of this, in the opinion of the compilers of the encyclopedia, is Dostoevsky's work "The Jewish Question". However, Dostoevsky himself in the "Jewish question" asserted: "... in my heart this hatred was never ...".

The writer Andrei Dikiy attributes the following quote to Dostoevsky:

“The Jews will destroy Russia and become the head of anarchy. The Jew and his kagal are a conspiracy against the Russians. "

Dostoevsky's attitude to the “Jewish question” is analyzed by the literary critic Leonid Grossman in his article “Dostoevsky and Judaism” and the book “Confessions of a Jew”, dedicated to the correspondence between the writer and Jewish journalist Arkady Kovner. The message to the great writer sent by Kovner from the Butyrka prison made an impression on Dostoevsky. He ends his letter in reply with the words "Believe in the complete sincerity with which I shake your hand outstretched to me," and in the chapter on the Jewish question of the "Diary of a Writer" he extensively quotes Kovner.

According to the critic Maya Turovskaya, the mutual interest of Dostoevsky and the Jews is caused by the incarnation in the Jews (and in Kovner, in particular) of the search for Dostoevsky's characters.

According to Nikolai Nasedkin, a contradictory attitude towards Jews is generally characteristic of Dostoevsky: he very clearly distinguished between the concepts of Jew and Jew. In addition, Nasedkin also notes that the word "Jew" and its derivatives were for Dostoevsky and his contemporaries a common word-toolkit among others, was used widely and everywhere, it was natural for all Russian literature of the 19th century, in contrast to modern times ..

It should be noted that Dostoevsky's attitude to the "Jewish question", which is not subject to the so-called "public opinion", may have been associated with his religious beliefs (see Christianity and anti-Semitism) [source?].

According to BV Sokolov, Dostoevsky's quotes were used by the Nazis during the Great Patriotic War for propaganda in the occupied territories of the USSR, for example, this one from the article "The Jewish Question":

What if it were not for Jews there were three million in Russia, but Russians, and there would be 160 million Jews (in the original Dostoevsky had 80 million, but the country's population was doubled - to make the quote more relevant. - B.S.) - well What would the Russians turn to and how would they treat them? Would they have allowed them to equal themselves in rights? Would you let them pray freely among them? Wouldn't they be turned into slaves? Even worse: would they not have flayed their skin at all, would not have beaten to the ground, until the final extermination, as they did with foreign peoples in the old days? "

Bibliography

Novels

* 1845 - Poor people

* 1861 - Humiliated and insulted

* 1866 - Crime and Punishment

* 1866 - The Player

* 1868 - Idiot

* 1871-1872 - Demons

* 1875 - Teenager

* 1879-1880 - Brothers Karamazov

Stories and stories

* 1846 - The Double

* 1846 - How Dangerous it is to indulge in ambitious dreams

* 1846 - Mr. Prokharchin

* 1847 - A novel in nine letters

* 1847 - Mistress

* 1848 - Sliders

* 1848 - Weak heart

* 1848 - Netochka Nezvanova

* 1848 - White nights

* 1849 - Little Hero

* 1859 - Uncle's dream

* 1859 - The village of Stepanchikovo and its inhabitants

* 1860 - Someone else's wife and husband under the bed

* 1860 - Notes from the House of the Dead

* 1862 - Winter Notes on Summer Impressions

* 1864 - Notes from the Underground

* 1864 - Bad anecdote

* 1865 - Crocodile

* 1869 - Eternal husband

* 1876 - Meek

* 1877 - The dream of a funny man

* 1848 - An Honest Thief

* 1848 - Christmas tree and wedding

* 1876 - The boy at Christ's on the tree

Publicism and criticism, essays

* 1847 - Petersburg Chronicle

* 1861 - The stories of N.V. Uspensky

* 1880 - The verdict

* 1880 - Pushkin

Writer's diary

* 1873 - Diary of a writer. 1873 year.

* 1876 - Diary of a writer. 1876

* 1877 - Diary of a writer. January-August 1877.

* 1877 - Diary of a writer. September-December 1877.

* 1880 - Diary of a writer. 1880

* 1881 - Diary of a writer. 1881 year.

Poems

* 1854 - On European events in 1854

* 1855 - On July 1, 1855

* 1856 - For coronation and peace

* 1864 - Epigram on the Bavarian colonel

* 1864-1873 - Fighting nihilism with honesty (officer and nihilist)

* 1873-1874 - Describe all of the priests alone

* 1876-1877 - The collapse of Baimakov's office

* 1876 - Children are expensive

* 1879 - Do not rob, Fedul

Standing apart is the collection of folklore material "My Convict Notebook", also known as "Siberian Notebook", written by Dostoevsky during his hard labor.

Main literature about Dostoevsky

Domestic research

* Belinsky V. G. [Introductory article] // St. Petersburg collection, published by N. Nekrasov. SPb., 1846.

* Dobrolyubov N.A. Hammered people // Contemporary. 1861. No. 9. dep. II.

* Pisarev D.I. Struggle for existence // Business. 1868. No. 8.

* Leontiev K.N.On world love: Concerning the speech of F.M.Dostoevsky at the Pushkin holiday // Warsaw diary. 1880. July 29 (No. 162). S. 3-4; August 7 (No. 169). S. 3-4; August 12 (No. 173). S. 3-4.

* Mikhailovsky N.K. Cruel talent // Otechestvennye zapiski. 1882. No. 9, 10.

* Solovyov V.S. Three speeches in memory of Dostoevsky: (1881-1883). M., 1884.55 p.

* Rozanov V.V. The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor F.M.Dostoevsky: The Experience of a Critical Commentary // Russian Bulletin. 1891.Vol. 212, January. S. 233-274; February. S. 226-274; T. 213, March. S. 215-253; April. S. 251-274. Separate ed .: St. Petersburg: Nikolaev, 1894.244 p.

* Merezhkovsky D. S. L. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky: Christ and the Antichrist in Russian literature. T. 1. Life and creativity. Saint Petersburg: World of Art, 1901.366 p. T. 2. The religion of L. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. SPb .: World of Art, 1902. LV, 530 p.

* Shestov L. Dostoevsky and Nietzsche. SPb., 1906.

* Ivanov Viach. I. Dostoevsky and the novel-tragedy // Russian thought. 1911. Book. 5.S. 46-61; Book. 6.S. 1-17.

* Pereverzev V. F. Creativity of Dostoevsky. M., 1912. (reprinted in the book: Gogol, Dostoevsky. Research. M., 1982)

* Tynyanov Yu. N. Dostoevsky and Gogol: (To the theory of parody). Pg .: OPOYAZ, 1921.

* Berdyaev N.A. Dostoevsky's world outlook. Prague, 1923.238 p.

* Volotskaya M.V. Chronicle of the Dostoevsky family 1506-1933. M., 1933.

* Engelgardt B. M. Dostoevsky's Ideological Novel // F. M. Dostoevsky: Articles and Materials / Ed. A. S. Dolinina. L .; M .: Thought, 1924. Sat. 2.S. 71-109.

* Dostoevskaya A.G. Memoirs. M .: Fiction, 1981.

* Freud Z. Dostoevsky and parricide // Classical psychoanalysis and fiction / Comp. and general ed. V. M. Leibin. SPb .: Peter, 2002.S. 70-88.

* Mochulsky K. V. Dostoevsky: Life and Work. Paris: YMCA-Press, 1947.564 pp.

* Lossky N.O. Dostoevsky and his Christian worldview. New York: Chekhov Publishing House, 1953.406 p.

* Dostoevsky in Russian criticism. Collection of articles. M., 1956. (introductory article and note by A. A. Belkin)

* Leskov NS About the peasant of the celebrities, etc. - Sobr. cit., t. 11, M., 1958. S. 146-156;

* Grossman L.P. Dostoevsky. M .: Molodaya gvardiya, 1962.543 p. (Life of wonderful people. Series of biographies; Issue 24 (357)).

* Bakhtin M. M. Problems of Dostoevsky's work. L .: Priboy, 1929.244 p. 2nd ed., Rev. and additional: Problems of Dostoevsky's poetics. M .: Soviet writer, 1963.363 p.

* Dostoevsky in the memoirs of his contemporaries: In 2 volumes. M., 1964.Vol. 1.Vol. 2.

* Friedlander G. M. Realism of Dostoevsky. M .; L .: Nauka, 1964.404 p.

* Meyer G. A. Light in the night: (On "Crime and Punishment"): Experience of slow reading. Frankfurt / Main: Posev, 1967.515 p.

* F. M. Dostoevsky: Bibliography of F. M. Dostoevsky's works and literature about him: 1917-1965. M .: Kniga, 1968.407 p.

* Kirpotin V. Ya. Disappointment and collapse of Rodion Raskolnikov: (A book about Dostoevsky's novel "Crime and Punishment"). M .: Soviet writer, 1970.448 p.

* Zakharov V.N. Problems of studying Dostoevsky: Textbook. - Petrozavodsk. 1978.

* Zakharov V.N. Dostoevsky's system of genres: Typology and poetics. - L., 1985.

* Toporov V. N. On the structure of Dostoevsky's novel in connection with archaic schemes of mythological thinking ("Crime and Punishment") // Toporov V. N. Myth. Ritual. Symbol. Image: Research in the field of mythopoetic. M., 1995.S. 193-258.

* Dostoevsky: Materials and Research / Academy of Sciences of the USSR. IRLI. L .: Science, 1974-2007. Issue 1-18 (continuing edition).

* Odinokov V. G. Typology of images in the artistic system of F. M. Dostoevsky. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1981.144 p.

* Seleznev Yu. I. Dostoevsky. M .: Molodaya gvardiya, 1981.543 p., Ill. (The life of wonderful people. Series of biographies; Issue 16 (621)).

* Volgin I. L. The Last Year of Dostoevsky: Historical Notes. M .: Soviet writer, 1986.

* Saraskina L. I. "Demons": a warning novel. M .: Soviet writer, 1990.488 p.

* Allen L. Dostoevsky and God / Per. with fr. E. Vorobieva. SPb .: Branch of the magazine "Youth"; Dusseldorf: The Blue Horseman, 1993.160 p.

* Guardini R. Man and Faith / Per. with him. Brussels: Life with God, 1994.332 p.

* Kasatkina T.A. The characterology of Dostoevsky: Typology of emotional-value orientations. Moscow: Heritage, 1996.335 p.

* Louth R. Dostoevsky's Philosophy in a Systematic Presentation / Per. with him. I. S. Andreeva; Ed. A. V. Gulygi. Moscow: Respublika, 1996.448 p.

* Balnep RL The structure of the "Brothers Karamazov" / Per. from English SPb .: Academic project, 1997.

* Dunaev M. M. Fedor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (1821-1881) // Dunaev M. M. Orthodoxy and Russian literature: [At 6 hours]. M .: Christian Literature, 1997.S. 284-560.

* Nakamura K. Dostoevsky's Feeling of Life and Death / Author. per. from japan. SPb .: Dmitry Bulanin, 1997.332 p.

* Meletinsky EM Notes on the work of Dostoevsky. Moscow: RGGU, 2001.190 p.

* Novel FM Dostoevsky "The Idiot": The current state of the study. Moscow: Heritage, 2001.560 p.

* Kasatkina T. A. On the creative nature of the word: The ontological nature of the word in the works of F. M. Dostoevsky as the basis of "realism in the highest sense." Moscow: IMLI RAN, 2004.480 p.

* Tikhomirov B. N. “Lazar! Come Out ": FM Dostoevsky's novel" Crime and Punishment "in a modern reading: Book-commentary. Saint Petersburg: Silver Age, 2005.472 p.

* Yakovlev L. Dostoevsky: ghosts, phobias, chimeras (reader's notes). - Kharkov: Karavella, 2006 .-- 244 p. ISBN 966-586-142-5

* Vetlovskaya V. E. Dostoevsky's novel "The Brothers Karamazov". SPb .: Publishing house "Pushkin House", 2007. 640 p.

* The novel by FM Dostoevsky "The Brothers Karamazov": the current state of study. Moscow: Nauka, 2007.835 p.

* Bogdanov N., Rogovoy A. Genealogy of the Dostoevsky. In search of lost links., M., 2008.

* John Maxwell Coetzee. "Autumn in St. Petersburg" (this is the name of this work in the Russian translation, in the original the novel is entitled "The Master from St. Petersburg"). M .: Eksmo, 2010.

* Openness to the abyss. Meetings with Dostoevsky Literary, philosophical and historiographic work of the culturologist Grigory Pomerants.

Foreign research:

English:

* Jones M.V. Dostoevsky. The novel of discord. L., 1976.

* Holquist M. Dostoievvsky and the novel. Princeton (N. Jersey), 1977.

* Hingley R. Dostoyevsky. His life and work. L., 1978.

* Kabat G.C. Ideology and imagination. The image of society in Dostoevsky. N.Y., 1978.

* Jackson R.L. The art of Dostoevsky. Princeton (N. Jersey), 1981.

* Dostoevsky Studies. Journal of the International Dostoievsky Society. v. 1 -, Klagenfurt-kuoxville, 1980-.

German:

* Zweig S. Drei Meister: Balzac, Dickens, Dostojewskij. Lpz., 1921.

* Natorp P.G: F. Dosktojewskis Bedeutung fur die gegenwartige Kulurkrisis. Jena, 1923.

* Kaus O. Dostojewski und sein Schicksal. B., 1923.

* Notzel K. Das Leben Dostojewskis, Lpz., 1925

* Meier-Crafe J. Dostojewski als Dichter. B., 1926.

* Schultze B. Der Dialog in F.M. Dostoevskijs "Idiot". Munchen, 1974.

Screen adaptations

* Fyodor Dostoevsky (English) on the Internet Movie Database

* Petersburg Night - a film by Grigory Roshal and Vera Stroeva based on Dostoevsky's novellas "Netochka Nezvanov" and "White Nights" (USSR, 1934)

* White Nights - a film by Luchino Visconti (Italy, 1957)

* White Nights - a film by Ivan Pyriev (USSR, 1959)

* White Nights - a film by Leonid Kvinikhidze (Russia, 1992)

* Beloved - a film by Sanjay Leela Bhansalia based on Dostoevsky's novel "White Nights" (India, 2007)

* Nikolai Stavrogin - a film by Yakov Protazanov based on Dostoevsky's novel "Demons" (Russia, 1915)

* Demons - film by Andrzej Wajda (France, 1988)

* Demons - a film by Igor and Dmitry Talankin (Russia, 1992)

* Demons - a film by Felix Schultess (Russia, 2007)

* The Brothers Karamazov - a film by Viktor Turyansky (Russia, 1915)

* The Brothers Karamazov - a film by Dmitry Bukhovetsky (Germany, 1920)

* The killer Dmitry Karamazov - a film by Fyodor Otsep (Germany, 1931)

* The Brothers Karamazov - a film by Richard Brooks (USA, 1958)

* The Brothers Karamazov - a film by Ivan Pyriev (USSR, 1969)

* Boys - a free fantasy film based on the novel by Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky "The Brothers Karamazov" by Renita Grigorieva (USSR, 1990)

* The Brothers Karamazov - a film by Yuri Moroz (Russia, 2008)

* The Karamazovs - film by Petr Zelenka (Czech Republic - Poland, 2008)

* Eternal Husband - a film by Evgeny Markovsky (Russia, 1990)

* Eternal Husband - Film by Denis Granier-Defer (France, 1991)

* Uncle's Dream - a film by Konstantin Voinov (USSR, 1966)

* 1938, France: The Gambler (French Le Joueur) - director: Louis Daken (French)

* 1938, Germany: "The Gamblers" (German: Roman eines Spielers, Der Spieler) - director: Gerhard Lampert (German)

* 1947, Argentina: "The Gambler" (Spanish El Jugador) - directed by Leon Klimovski (Spanish)

* 1948, USA: "The great sinner" - director: Robert Siodmak

* 1958, France: "The Gambler" (French Le Joueur) - director: Claude Otan-Lara (French)

* 1966, - USSR: "The Gambler" - director Bogatyrenko Yuri

* 1972: The Gambler - Director: Michail Olschewski

* 1972, - USSR: "The Gambler" - director Alexei Batalov

* 1974 USA: The Gambler - directed by Karel Rice

* 1997, Hungary: The Gambler - directed by Mac Carola (Hungarian)

* 2007, Germany: "The Gamblers" (German: Die Spieler, English The Gamblers) - director: Sebastian Binjeck (German)

* "The Idiot" - a film by Pyotr Chardynin (Russia, 1910)

* "The Idiot" - a film by Georges Lampen (France, 1946)

* "The Idiot" - a film by Akira Kurosawa (Japan, 1951)

* "The Idiot" - a film by Ivan Pyriev (USSR, 1958)

* "The Idiot" - TV series by Alan Bridges (UK, 1966)

* "Crazy Love" - a film by Andrzej Zulawski (France, 1985)

* "The Idiot" - TV series Mani Kaula (India, 1991)

* "Down House" - a film-interpretation by Roman Kachanov (Russia, 2001)

* "The Idiot" - TV series by Vladimir Bortko (Russia, 2003)

* Meek - a film by Alexander Borisov (USSR, 1960)

* Meek - film-interpretation of Robert Bresson (France, 1969)

* Meek - a drawn cartoon film by Petr Dumala (Poland, 1985)

* Meek - a film by Avtandil Varsimashvili (Russia, 1992)

* Meek - a film by Evgeny Rostovsky (Russia, 2000)

* Dead House (prison of peoples) - a film by Vasily Fedorov (USSR, 1931)

* Partner - film by Bernardo Bertolucci (Italy, 1968)

* Teenager - a film by Evgeny Tashkov (USSR, 1983)

* Raskolnikov - a film by Robert Wien (Germany, 1923)

* Crime and Punishment - a film by Pierre Chenal (France, 1935)

* Crime and Punishment - film by Georges Lampen (France, 1956)

* Crime and Punishment - a film by Lev Kulidzhanov (USSR, 1969)

* Crime and Punishment - Aki Kaurismäki's film (Finland, 1983)

* Crime and Punishment - hand-drawn cartoon film by Piotr Dumala (Poland, 2002)

* Crime and Punishment - Film by Julian Jarold (UK, 2003)

* Crime and Punishment - TV series by Dmitry Svetozarov (Russia, 2007)

* Dream of a funny man - cartoon by Alexander Petrov (Russia, 1992)

* The village of Stepanchikovo and its inhabitants - TV movie by Lev Tsutsulkovsky (USSR, 1989)

* A nasty anecdote - a comedy film by Alexander Alov and Vladimir Naumov (USSR, 1966)

* Humiliated and insulted - TV movie Vittorio Cottafavi (Italy, 1958)

* Humiliated and Insulted - TV series by Raul Araisa (Mexico, 1977)

* Humiliated and insulted - a film by Andrei Eshpai (USSR - Switzerland, 1990)

* Another's wife and husband under the bed - a film by Vitaly Melnikov (USSR, 1984)

Films about Dostoevsky

* "Dostoevsky". Documentary. TsSDF (RTSSDF). 1956.27 minutes. - a documentary film by Bubrik Samuil and Ilya Kopalin (Russia, 1956) about the life and work of Dostoevsky on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of his death.

* The writer and his city: Dostoevsky and Petersburg - a film by Heinrich Böll (Germany, 1969)

* Twenty-six days in the life of Dostoevsky - a feature film by Alexander Zarkhi (USSR, 1980; starring Anatoly Solonitsyn)

* Dostoevsky and Peter Ustinov - from the documentary "Russia" (Canada, 1986)

* The return of the prophet - a documentary film by V.E. Ryzhko (Russia, 1994)

* The life and death of Dostoevsky - documentary (12 episodes) Klyushkin Alexander (Russia, 2004)

* Demons of St. Petersburg - feature film by Giuliano Montaldo (Italy, 2008)

* Three women of Dostoevsky - a film by Evgeny Tashkov (Russia, 2010)

* Dostoevsky - TV series by Vladimir Khotinenko (Russia, 2011) (starring Yevgeny Mironov).

The image of Dostoevsky is also used in the biographical films Sophia Kovalevskaya (Alexander Filippenko) and Chokan Valikhanov (1985).

Current events

* On October 10, 2006, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Federal Chancellor of Germany Angela Merkel unveiled a monument to Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky in Dresden by People's Artist of Russia Alexander Rukavishnikov.

* A crater on Mercury is named in honor of Dostoevsky (Latitude:? 44.5, Longitude: 177, Diameter (km): 390).

* Writer Boris Akunin wrote the work “F. M. ", dedicated to Dostoevsky.

* In 2010, director Vladimir Khotinenko began filming a multi-part film about Dostoevsky, which will be released in 2011 on the occasion of the 190th anniversary of Dostoevsky's birth.

* On June 19, 2010, the 181st station of the Moscow metro "Dostoevskaya" was opened. The exit to the city is carried out on Suvorovskaya square, Seleznevskaya street and Durov street. Station decoration: the walls of the station depict scenes illustrating four novels by FM Dostoevsky (Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, The Demons, The Brothers Karamazov).

Notes (edit)

1 IF Masanov, "Dictionary of pseudonyms of Russian writers, scientists and public figures." In 4 volumes. - M., All-Union Book Chamber, 1956-1960.

2 1 2 3 4 5 November 11 // RIA Novosti, November 11, 2008

3 Mirror of the week. - No. 3. - January 27 - February 2, 2007

4 Panaev I. I. Memories of Belinsky: (Fragments) // I. I. Panaev. From "literary memoirs" / Executive editor N. K. Piksanov. - A series of literary memoirs. - L .: Fiction, Leningrad branch, 1969. - 282 p.

5 Igor Zolotussky. String in the fog

6 Semipalatinsk. Memorial House-Museum of F.M.Dostoevsky

7 [Troyes Henri. Fedor Dostoevsky. - Moscow: Eksmo Publishing House, 2005 .-- 480 p. (Series "Russian Biographies"). ISBN 5-699-03260-6

8 1 2 3 4 [Henri Troyes. Fedor Dostoevsky. - Moscow: Eksmo Publishing House, 2005 .-- 480 p. (Series "Russian Biographies"). ISBN 5-699-03260-6

9 On the building located in the place where the hotel where the Dostoevskys stayed was, in December 2006, a memorial plaque was unveiled (by the sculptor Romualdas Kvintas) A memorial plaque to Fyodor Dostoevsky was unveiled in the center of Vilnius

10 History of the Zaraysky district // Official site of the Zaraysky municipal district

11 Nogovitsyn O. M. “Poetics of Russian prose. Metaphysical research ", VRFS, SPb., 1994

12 Ilya Brazhnikov. Dostoevsky Fyodor Mikhailovich (1821-1881).

13 F. M. Dostoevsky, "A Writer's Diary". 1873 year. Chapter XI. "Dreams and Dreams"

14 Dostoevsky Fyodor. Electronic Jewish Encyclopedia

15 F.M.Dostoevsky. The Jewish Question on Wikisource

16 Dikiy (Zankevich), Andrey Russian-Jewish Dialogue, section "F. M. Dostoevsky about the Jews." Retrieved June 6, 2008.

17 1 2 Nasedkin N., Minus Dostoevsky (F. M. Dostoevsky and the "Jewish question")

18 L. Grossman "Confessions of a Jew" and "Dostoevsky and Judaism" in the Imwerden library

19 Maya Turovskaya. Jew and Dostoevsky, "Zarubezhnye zapiski" 2006, no. 7

20 B. Sokolov. An occupation. Truth and myths

21 "Fools". Alexey Osipov - Doctor of Theology, professor at the Moscow Theological Academy.

22 http://www.gumer.info/bogoslov_Buks/Philos/bened/intro.php (see box 17)

Fedor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky

11.11.1821 - 27.01.1881

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, Russian writer, was born in 1821 in Moscow. His father was a nobleman, landowner and doctor of medicine.

He was brought up to 16 years old in Moscow. In the seventeenth year he passed the exam in St. Petersburg at the Main Engineering School. In 1842 he graduated from the military engineering course and left the school as an engineer-second lieutenant. He was left in the service in St. Petersburg, but other goals and aspirations attracted him irresistibly. He became especially interested in literature, philosophy and history.

In 1844 he retired and at the same time wrote his first rather large story, Poor People. This story at once created a position for him in literature, was met with criticism and the best Russian society extremely favorably. It was a rare success in the full sense of the word. But the constant ill health that followed for several years in a row harmed his literary pursuits.

In the spring of 1849, he was arrested along with many others for participating in a political conspiracy against the government, which had a socialist connotation. He was committed to the investigation and the highest appointed military court. After eight months in the Peter and Paul Fortress, he was sentenced to death by shooting. But the sentence was not carried out: the mitigation of the sentence was read and Dostoevsky, after being deprived of the rights of state, ranks and nobility, was exiled to Siberia to hard labor for four years, with enrollment at the end of the term of hard labor in ordinary soldiers. This verdict over Dostoevsky was, in its form, the first ever case in Russia, for anyone sentenced to hard labor in Russia loses his civil rights forever, even if he ends his term of hard labor. Dostoevsky, on the other hand, was appointed, after serving the term of hard labor, to enter the soldier - that is, the rights of a citizen were returned again. Subsequently, such pardons happened more than once, but then this was the first case and happened at the behest of the late Emperor Nicholas I, who regretted his youth and talent in Dostoevsky.

In Siberia, Dostoevsky served his four-year term of hard labor in the fortress of Omsk; and then in 1854 he was sent from penal servitude as an ordinary soldier to the Siberian line battalion _ 7 in the city of Semipalatinsk, where a year later he was promoted to non-commissioned officers, and in 1856, with the accession to the throne of the now reigning emperor Alexander II, to officers. In 1859, being in an epileptic illness, acquired while still in hard labor, he was dismissed and returned to Russia, first to the city of Tver, and then to St. Petersburg. Here Dostoevsky began to study literature again.

In 1861, his elder brother, Mikhail Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, began to publish a monthly large literary magazine ("Revue") - "Time". F. M. Dostoevsky also took part in the publication of the magazine, having published his novel "The Humiliated and the Offended" in it, which was sympathetically received by the public. But in the next two years he began and finished Notes from the House of the Dead, in which, under assumed names, he told his life in hard labor and described his former comrades-convicts. This book was read by the whole of Russia and is still highly valued, although the orders and customs described in Notes from the House of the Dead have long since changed in Russia.

In 1866, after the death of his brother and after the termination of the journal "Epoch" published by him, Dostoevsky wrote the novel "Crime and Punishment", then in 1868 - the novel "The Idiot" and in 1870 the novel "Demons". These three novels were highly appreciated by the public, although Dostoevsky, perhaps, treated them too harshly towards modern Russian society.

In 1876, Dostoevsky began to publish a monthly magazine under the original form of his "Diary", written by him alone, without collaborators. This edition was published in 1876 and 1877. in the amount of 8000 copies. It was successful. In general, Dostoevsky is loved by the Russian public. He deserved even from literary opponents his opinion of a highly honest and sincere writer. By his convictions, he is an open Slavophile; his former socialist convictions have changed quite dramatically.

Brief biographical information dictated by the writer A. G. Dostoevskaya (Published in the January 1881 issue of the "Writer's Diary").

Dostoevsky Fyodor Mikhailovich