Vladimir Belyaev: The old fortress. Reviews for the book "Old Fortress

Read also

"If it happens to any of the readers of the" Old Fortress "to get to Kamenets-Podolsky, through all the layers of the new, he will definitely recognize in it the city of Vasil Mandzhura and Petka Maremukha, the hometown of the author of the trilogy, although it is not named anywhere in the book. no matter how long a visitor has read this book, he will immediately feel that amazing, full of romance, the flavor of so much surviving Ukrainian town that the author was able to convey with a truly poetic talent in the first part of his trilogy, arises in his memory. "

S.S. Smirnov, Lenin Prize Laureate. From the preface to the book.

Parts of the trilogy "The Old Fortress" were written by Vladimir Belyaev in different years: "The Old Fortress" - 1936,

"Haunted House" - 1941, "City by the Sea" - 1950.

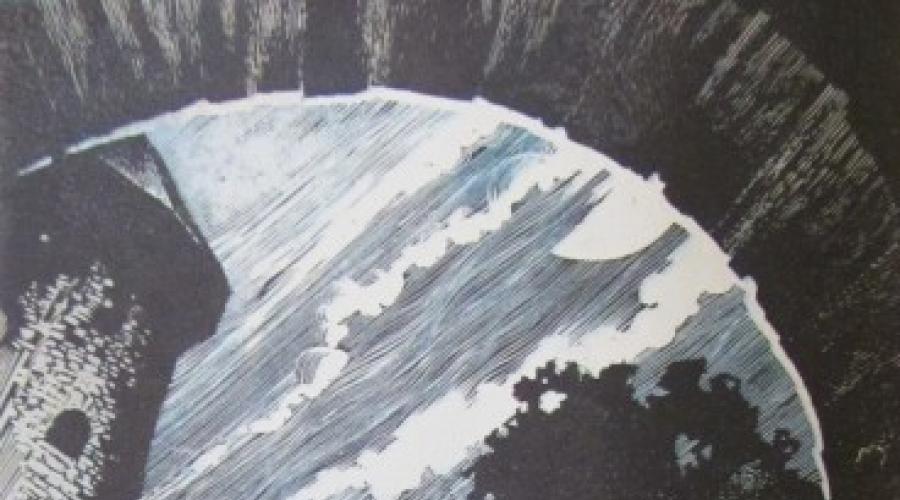

The 1984 edition was illustrated by the Ukrainian graphic artist Pavel Anatolyevich Krysachenko.

I often come across the opinion that Vladimir Belyaev described his hometown Kamenets-Podolsky quite accurately in the book and from the text you can understand in which real city objects his heroes live, study, work and where they are located.

In fact, this is not the case. The author created a collective image of an ancient Ukrainian city with a fortress, churches, churches, educational institutions, etc., without setting himself the goal of exact correspondence. This can be seen if we compare even a small fragment of the book with reality.

The beginning of the first book:

“We have become high school students quite recently. Previously, all our lads studied at the city high school. Its yellow walls and green fence are clearly visible from the District. And let’s run to be in time for lessons. And keep up. You rush along Steep Lane, fly a wooden bridge, then up a rocky path - to Old Boulevard, and now you have a school gate in front of you. ......

Three windows in our class overlook the Old Fortress and two - to the District. If you get tired of listening to the teacher, you can look out the windows. I looked to the right - the Old Fortress with all its nine towers rises above the rocks. And you will look to the left - there is our native District. From the windows of the school you can

make out every street, every house. "

First of all, it must be said that there was no district Zarechye in Kamenets, neither officially nor in the popular name. There was a place name Backwater, For water- so called Onufrievskaya street, located on a narrow strip of the left bank of the Smotrich.

To begin with, let's decide where the District is located according to the book.

The school, as we understand it, is in the Old Town: on the Old Boulevard or next to it.

A steep lane is located in the District. The district and the Old Town are separated by a river. A wooden bridge connects these two areas

"You rush along Steep Lane, fly over a wooden bridge, then up a rocky path - to Old Boulevard, and now you have a school gate in front of you."

Let's imagine that the District is Polish farms.

Indeed, a wooden bridge (now a stone one) leads from there to the Old Town.

There is a wooden bridge, but instead of a path, there is a comfortable stone staircase from Farengolts. It is difficult to imagine a "rocky path" in this place.

This is the place by the wooden bridge:

In the next two photos we see another bridge from the Polish farm to the Old Town. Along the "rocky path" near the Tower on the ford, through Kuznechnaya Street, you can just get out to Old Boulevard.

But then we run into the main discrepancy: if the school is located here, then the fortress is to the left of it, and the District (Polish farmsteads) is located directly and to the right, that is, not like Belyaev's:

"Three windows in our class overlook the Old Fortress and two - to the District.

I looked to the right - the Old Fortress with all its nine towers rises above the rocks.

And you will look to the left - there is our native District "

Let's imagine that the District is Russian Folvarks.

From here to the Old Town there is a small wooden bridge (masonry), but there is not and cannot be a "rocky path". There is a staircase and a Castle Bridge. There are steep rocks to the right and left.

Where was the school located?

We remember that both the fortress and the District are visible from its windows.

Assuming that the school is located in buildings on the cliff to the right of the bridge,

then we can assume that this is similar to Belyaev's description: the fortress on the right, the District on the left. In addition, the buildings of this part of the Russian Farms are clearly visible from the windows of the buildings.

"From the windows of the school, you can see every street, every house."

But these buildings are not located on the Old Boulevard, moreover, both on the Russians and on the Polish farms, it is difficult to understand which lane Belyaev called Cool.

"You rush along Steep Lane, fly over a wooden bridge, then up

rocky path - to the Old Boulevard, and now in front of you the school

Gates".

The name Starobulvarna is currently the street that stretches from the Trinitarian Church to the Town Hall on the Polish Market. Once the Old Boulevard was called the one that runs along the walls of the monasteries of the Franciscans and Dominicans. If the building of the school was on the Old Boulevard above the rock (which in reality is unlikely), then the fortress would be visible from its windows, but the Zarechye-Russian Folvarks would not be visible.

Where was the Old Manor?

"Having passed the Assumption Church, along the narrow Steep Lane, we turned to ... Through the bushes and weeds we rushed to the Old Estate."

This question could be answered if we determined the locations of the District, but we did not succeed. In addition, it is impossible to understand which church Belyaev called the Assumption. The Assumption Church in Kamenets was once located in the area of the Turkish bastion, i.e. not in the District, as in Belyaev, but in the Old Town. And in 1700, the Assumption Church no longer existed - it was destroyed during

There are similar inconsistencies with reality in other parts of the book, but this does not prevent you from reading with pleasure the wonderful work of the stone resident Vladimir Belyaev.

In 1972, at the film studio. A. Dovzhenko, a seven-part feature film "The Old Fortress" was shot, most of which were filmed in Kamenets.

The action-packed trilogy "The Old Fortress" by Vladimir Belyaev is based on the events of the first post-revolutionary decade. The book was reprinted more than thirty times, including in the Golden Library series, and was filmed twice - in 1938 (1st part) and 1955 (under the title "Anxious Youth").

The idea of a story about the fate of boys from a small Ukrainian town, who found themselves in the thick of the civil war, was thrown to Belyaev by S.Ya. Marshak. The author himself called his brainchild, work on which continued until 1967, "a diary of memories", so strong were autobiographical motives in it. In fact, I myself recently learned that all three stories are a kind and rather detailed autobiography of Belyaev.

The formation of the character of a teenage worker, a new Soviet man is the main theme of the trilogy, perhaps for us now this is not relevant, but in those days such books were welcomed.

If you do not delve into the patriotic and ideological considerations of the trilogy, then we can say that Belyaev wrote an interesting and adventure book for teenage boys.

The trilogy consists of the following books:

Old Fortress

House with the ghosts

City by the sea

The first part of the book tells about the childhood of boys, about quarrels, conflicts, dividing the street, jumping on a bet into a deep river from a bridge. I think, to show the patriotic orientation of the story, Belyaev introduced into the plot a moment when the boys climbed into an old mysterious manhole to explore the old abandoned part of the fortress and ended up at the end of the path in the garden. Night fell, and the guys involuntarily witnessed the execution of the Red Army soldier. The death of a man who had recently communicated with them, smiled, shocked the boys to the core. Which, by the way, pushed them to even more hatred towards the White Guards.

The episodes of studying at the gymnasium, the incident with the old bells are well spelled out. The first part, in my opinion, is the strongest in terms of adventure.

The second part of the book already shows the world of grown-up friends, the first timid feelings of love for a neighbor's girl, a desire to stand out and be liked against the background of other guys. The moment when the protagonist of the book invites his neighbor Valya to the cinema, and then leads her to the pastry shop, I especially sunk into the memory. The young gentleman, of course, has no money for these events. And he decides to steal the aunt's silver spoons, which make up all her wealth for the aunt. As a sin, the father will see the unlucky couple of children in the cafe, the spoons will soon come out and will have to confess everything.

In the final part of the book, yesterday's boys have become adults. Here in the plot the main place was taken by the Great Patriotic War, memories from childhood about friendship and the fact that many children are no longer alive.

Page after page takes us through almost forty years of the protagonists' lives.

The book is probably more focused on our generation, it is clearer and clearer to us, we will more correctly perceive the description of the political turmoil in the country. But my son sometimes even had to explain some points, give examples from the past, so that the plot and the idea of that state, which had long ago become different, could be fully understood.

We do not regret buying these wonderful pieces at all.

In the tradition of the series, the book was published on newsprint a little grayish, but overall, of high quality. The lacquered white cover and red letters are the hallmark of this series.

Vladimir BELYAEV

Old fortress

Book one

Old fortress

A HISTORY TEACHER

We have become high school students quite recently.

Previously, all our lads studied at the city higher primary school.

Its yellow walls and green fence are clearly visible from the District.

If they called at the schoolyard, we heard the call at our place, in the District. Grab your books, pencil case with pencils - and let's run to be in time for lessons.

And they kept up.

You rush along Steep Lane, fly over a wooden bridge, then up a rocky path - to Old Boulevard, and now there is a school gate in front of you.

As soon as you have time to run into the classroom and sit down at the desk, the teacher comes in with a magazine.

Our class was small, but very bright, the aisles between the desks were narrow, and the ceilings were low.

Three windows in our class overlook the Old Fortress and two - to the District.

If you get tired of listening to the teacher, you can look out the windows.

I looked to the right - the Old Fortress with all its nine towers rises above the rocks.

And you will look to the left - there is our native District. From the windows of the school, you can see every street, every house.

Here in the Old Manor, Petka's mother went out to hang clothes: you can see how the wind blows bubbles in the big shirts of Petka's father, the shoemaker Maremukha.

But from Krutoy Lane left to catch dogs the father of my friend Yuzik - bow-legged Starodomsky. One can see how his black oblong van - a dog's prison - is jumping up and down on the rocks. Starodomsky turns his skinny nag to the right and drives past my house. Blue smoke billows from our kitchen chimney. This means that aunt Marya Afanasyevna has already melted the stove.

Wondering what will be for lunch today? Young potatoes with sour milk, hominy with uzvar or corn on the cob?

"Now, if only fried dumplings!" - I dream. I love fried dumplings with giblets the most. Is it possible to compare with them young potatoes or buckwheat porridge with milk? Never!

Once in a lesson I was dreaming, looking out of the windows at the District, and suddenly, above my ear, the teacher's voice:

Come on, Manjura! Go to the board - help Bean ...

Slowly I leave from behind my desk, I look at the guys, and I don’t know what to help.

Freckled Sashka Bobyr, shifting from foot to foot, is waiting for me at the board. He even got chalk on his nose.

I go up to him, take the chalk and so that the teacher does not notice, I blink at my friend Yuzik Starodomsky, nicknamed the Marten.

The marten, watching the teacher, folds his hands in a boat and whispers:

Bisector! Bisector!

And what kind of bird is this, bisector? Also, they say, prompted!

The mathematician has already approached the board with even, calm steps.

Well, young man, are you thinking?

But suddenly, at that very moment, a bell rings in the courtyard.

Bisector, Arkady Leonidovich, this is ... - I start smartly, but the teacher no longer listens to me and goes to the door.

"Cleverly twisted," I think, "otherwise I would have slapped one ..."

We loved the historian Valerian Dmitrievich Lazarev more than all the teachers in the higher primary school.

He was short, white-haired, he always wore a green sweatshirt with sleeves patched at the elbows - at first glance he seemed to us the most ordinary teacher, so-so - neither fish nor meat.

When Lazarev first came to class, before talking to us, he coughed for a long time, rummaged in a class magazine and wiped his pince-nez.

Well, the goblin brought another four-eyed one ... - Yuzik whispered to me.

We were going to invent a nickname for Lazarev, but when we got to know him better, we immediately recognized him and loved him deeply, truly, as we had not loved any of the teachers until now.

Where has it been seen before that the teacher easily walked around the city with the students?

And Valerian Dmitrievich was walking.

Often, after history lessons, he gathered us and, squinting slyly, suggested:

Today I'm going to the fortress after school. Who wants with me?

There were many hunters. Who will refuse to go there with Lazarev?

Valerian Dmitrievich knew every stone in the Old Fortress.

Once a whole Sunday, until the very evening, Valerian Dmitrievich and I spent in the fortress. He told us a lot of interesting things that day. We then learned from him that the smallest tower is called Ruzhanka, and the dilapidated one that stands near the fortress gate was nicknamed by a strange name - Donna. And near Donna, the tallest of all, the Papal Tower, rises above the fortress. It stands on a wide quadrangular foundation, octahedral in the middle, and round at the top, under the roof. Eight dark loopholes look beyond the city, to the District, and into the depths of the fortress yard.

Already in distant antiquity, - Lazarev told us, - our region was famous for its wealth. The land here gave birth very well, in the steppes there was such tall grass that the horns of the largest ox were invisible from afar. The plow, often forgotten in the field, was covered with thick, succulent grass in three or four days. There were so many bees that all of them could not accommodate in the hollows of trees and therefore swarmed right in the ground. It happened that from under the feet of a passer-by, streams of excellent honey were sprayed. Along the entire coast of the Dniester, delicious wild grapes grew without any supervision, native apricots and peaches ripened.

Our land seemed especially sweet to the Turkish sultans and neighboring Polish landowners. They rushed here with all their might, set up their lands here, wanted to conquer the Ukrainian people with fire and sword.

Lazarev said that only a hundred years ago there was a transit prison in our Old Fortress. In the walls of the destroyed white building in the fortress courtyard, gratings are still preserved. Behind them sat the prisoners who, by order of the tsar, were sent to Siberia to hard labor. The famous Ukrainian rebel Ustin Karmelyuk languished in the Papal Tower under Tsar Nicholas the First. With his brothers-in-arms, he caught the gentlemen, police officers, priests, bishops passing through the Kalinovsky forest, took money from them, horses and distributed everything taken away to the poor peasants. The peasants hid Karmelyuk in the cellars, in the heaps on the field, and none of the tsar's detectives for a long time could catch the brave rebel. He escaped from distant penal servitude three times. They beat him, but how they beat him! Karmelyuk's back withstood more than four thousand blows with gauntlets and batogs. Hungry, wounded, every time he escaped from prison and through the frosty deep taiga, for weeks without seeing a piece of stale bread, he made his way to his homeland - to Podolia.

Vladimir BELYAEV

Old fortress

A HISTORY TEACHER

We have become high school students quite recently.

Previously, all our lads studied at the city higher primary school.

Its yellow walls and green fence are clearly visible from the District.

If they called at the schoolyard, we heard the call at our place, in the District. Grab your books, pencil case with pencils - and let's run to be in time for lessons.

And they kept up.

You rush along Steep Lane, fly over a wooden bridge, then up a rocky path - to Old Boulevard, and now there is a school gate in front of you.

As soon as you have time to run into the classroom and sit down at the desk, the teacher comes in with a magazine.

Our class was small, but very bright, the aisles between the desks were narrow, and the ceilings were low.

Three windows in our class overlook the Old Fortress and two - to the District.

If you get tired of listening to the teacher, you can look out the windows.

I looked to the right - the Old Fortress with all its nine towers rises above the rocks.

And you will look to the left - there is our native District. From the windows of the school, you can see every street, every house.

Here in the Old Manor, Petka's mother went out to hang clothes: you can see how the wind blows bubbles in the big shirts of Petka's father, the shoemaker Maremukha.

But from Krutoy Lane left to catch dogs the father of my friend Yuzik - bow-legged Starodomsky. One can see how his black oblong van - a dog's prison - is jumping up and down on the rocks. Starodomsky turns his skinny nag to the right and drives past my house. Blue smoke billows from our kitchen chimney. This means that aunt Marya Afanasyevna has already melted the stove.

Wondering what will be for lunch today? Young potatoes with sour milk, hominy with uzvar or corn on the cob?

"Now, if only fried dumplings!" - I dream. I love fried dumplings with giblets the most. Is it possible to compare with them young potatoes or buckwheat porridge with milk? Never!

Once in a lesson I was dreaming, looking out of the windows at the District, and suddenly, above my ear, the teacher's voice:

Come on, Manjura! Go to the board - help Bean ...

Slowly I leave from behind my desk, I look at the guys, and I don’t know what to help.

Freckled Sashka Bobyr, shifting from foot to foot, is waiting for me at the board. He even got chalk on his nose.

I go up to him, take the chalk and so that the teacher does not notice, I blink at my friend Yuzik Starodomsky, nicknamed the Marten.

The marten, watching the teacher, folds his hands in a boat and whispers:

Bisector! Bisector!

And what kind of bird is this, bisector? Also, they say, prompted!

The mathematician has already approached the board with even, calm steps.

Well, young man, are you thinking?

But suddenly, at that very moment, a bell rings in the courtyard.

Bisector, Arkady Leonidovich, this is ... - I start smartly, but the teacher no longer listens to me and goes to the door.

"Cleverly twisted," I think, "otherwise I would have slapped one ..."

We loved the historian Valerian Dmitrievich Lazarev more than all the teachers in the higher primary school.

He was short, white-haired, he always wore a green sweatshirt with sleeves patched at the elbows - at first glance he seemed to us the most ordinary teacher, so-so - neither fish nor meat.

When Lazarev first came to class, before talking to us, he coughed for a long time, rummaged in a class magazine and wiped his pince-nez.

Well, the goblin brought another four-eyed one ... - Yuzik whispered to me.

We were going to invent a nickname for Lazarev, but when we got to know him better, we immediately recognized him and loved him deeply, truly, as we had not loved any of the teachers until now.

Where has it been seen before that the teacher easily walked around the city with the students?

And Valerian Dmitrievich was walking.

Often, after history lessons, he gathered us and, squinting slyly, suggested:

Today I'm going to the fortress after school. Who wants with me?

There were many hunters. Who will refuse to go there with Lazarev?

Valerian Dmitrievich knew every stone in the Old Fortress.

Once a whole Sunday, until the very evening, Valerian Dmitrievich and I spent in the fortress. He told us a lot of interesting things that day. We then learned from him that the smallest tower is called Ruzhanka, and the dilapidated one that stands near the fortress gate was nicknamed by a strange name - Donna. And near Donna, the tallest of all, the Papal Tower, rises above the fortress. It stands on a wide quadrangular foundation, octahedral in the middle, and round at the top, under the roof. Eight dark loopholes look beyond the city, to the District, and into the depths of the fortress yard.

Already in distant antiquity, - Lazarev told us, - our region was famous for its wealth. The land here gave birth very well, in the steppes there was such tall grass that the horns of the largest ox were invisible from afar. The plow, often forgotten in the field, was covered with thick, succulent grass in three or four days. There were so many bees that all of them could not accommodate in the hollows of trees and therefore swarmed right in the ground. It happened that from under the feet of a passer-by, streams of excellent honey were sprayed. Along the entire coast of the Dniester, delicious wild grapes grew without any supervision, native apricots and peaches ripened.

Our land seemed especially sweet to the Turkish sultans and neighboring Polish landowners. They rushed here with all their might, set up their lands here, wanted to conquer the Ukrainian people with fire and sword.

Lazarev said that only a hundred years ago there was a transit prison in our Old Fortress. In the walls of the destroyed white building in the fortress courtyard, gratings are still preserved. Behind them sat the prisoners who, by order of the tsar, were sent to Siberia to hard labor. The famous Ukrainian rebel Ustin Karmelyuk languished in the Papal Tower under Tsar Nicholas the First. With his brothers-in-arms, he caught the gentlemen, police officers, priests, bishops passing through the Kalinovsky forest, took money from them, horses and distributed everything taken away to the poor peasants. The peasants hid Karmelyuk in the cellars, in the heaps on the field, and none of the tsar's detectives for a long time could catch the brave rebel. He escaped from distant penal servitude three times. They beat him, but how they beat him! Karmelyuk's back withstood more than four thousand blows with gauntlets and batogs. Hungry, wounded, every time he escaped from prison and through the frosty deep taiga, for weeks without seeing a piece of stale bread, he made his way to his homeland - to Podolia.

Vladimir BELYAEV

Old fortress

A HISTORY TEACHER

We have become high school students quite recently.

Previously, all our lads studied at the city higher primary school.

Its yellow walls and green fence are clearly visible from the District.

If they called at the school yard, we heard the call at our place, in the District. Grab your books, pencil case with pencils - and let's go to run to be in time for lessons.

And they kept up.

You rush along Steep Lane, fly over a wooden bridge, then up a rocky path - to Old Boulevard, and now you have a school gate in front of you.

As soon as you have time to run into the classroom and sit down at the desk, the teacher comes in with a magazine.

Our class was small, but very bright, the aisles between the desks were narrow, and the ceilings were low.

Three windows in our class overlook the Old Fortress and two - to the District.

If you get tired of listening to the teacher, you can look out the windows.

I looked to the right - the Old Fortress with all its nine towers rises above the rocks.

And you will look to the left - there is our native District. From the windows of the school, you can see every street, every house.

Here in the Old Manor, Petka's mother went out to hang clothes: you can see how the wind blows bubbles in the big shirts of Petka's father, the shoemaker Maremukha.

But from Krutoy Lane left to catch dogs the father of my friend Yuzik - bow-legged Starodomsky. One can see how his black oblong van - a dog's prison - jumps on the rocks. Starodomsky turns his skinny nag to the right and drives past my house. Blue smoke billows from our kitchen chimney. This means that aunt Marya Afanasyevna has already melted the stove.

Wondering what will be for lunch today? Young potatoes with sour milk, hominy with uzvar or corn on the cob?

"Now, if only fried dumplings!" - I dream. I love fried dumplings with giblets the most. Is it possible to compare with them young potatoes or buckwheat porridge with milk? Never!

Once in a lesson I was dreaming, looking out of the windows at the District, and suddenly, above my ear, the teacher's voice:

- Come on, Manjura! Go to the board - help Bean ...

Slowly I leave from behind my desk, I look at the guys, and I don’t know what to help.

Freckled Sashka Bobyr, shifting from foot to foot, is waiting for me at the board. He even got chalk on his nose.

I go up to him, take the chalk and so that the teacher does not notice, I blink at my friend Yuzik Starodomsky, nicknamed the Marten.

The marten, watching the teacher, folds his hands in a boat and whispers:

- Bisector! Bisector!

And what kind of bird is this, bisector? Also, they say, prompted!

The mathematician has already approached the board with even, calm steps.

- Well, young man, are you thinking?

But suddenly, at that very moment, a bell rings in the courtyard.

- Bisector, Arkady Leonidovich, this is ... - I start smartly, but the teacher no longer listens to me and goes to the door.

"Cleverly twisted," I think, "otherwise I would have slapped one ..."

We loved the historian Valerian Dmitrievich Lazarev more than all the teachers in the higher primary school.

He was short, white-haired, he always wore a green sweatshirt with sleeves patched at the elbows - at first glance he seemed to us the most ordinary teacher, so-so - neither fish nor meat.

When Lazarev first came to class, before talking to us, he coughed for a long time, rummaged in a class magazine and wiped his pince-nez.

- Well, the goblin brought another four-eyed one ... - Yuzik whispered to me.

We were going to invent a nickname for Lazarev, but when we got to know him better, we immediately recognized him and loved him deeply, truly, as we had not loved any of the teachers until now.

Where has it been seen before that the teacher easily walked around the city with the students?

And Valerian Dmitrievich was walking.

Often, after history lessons, he gathered us and, squinting slyly, suggested:

- Today I'm going to the fortress after school. Who wants with me?

There were many hunters. Who will refuse to go there with Lazarev?

Valerian Dmitrievich knew every stone in the Old Fortress.

Once a whole Sunday, until the very evening, Valerian Dmitrievich and I spent in the fortress. He told us a lot of interesting things that day. We then learned from him that the smallest tower is called Ruzhanka, and the dilapidated one that stands near the fortress gate was nicknamed by a strange name - Donna. And near Donna, the tallest of all, the Papal Tower, rises above the fortress. It stands on a wide quadrangular foundation, octahedral in the middle, and round at the top, under the roof. Eight dark loopholes look beyond the city, to the District, and into the depths of the fortress yard.

“Already in ancient times,” Lazarev told us, “our land was famous for its wealth. The land here gave birth very well, in the steppes there was such tall grass that the horns of the largest ox were invisible from afar. The plow, often forgotten in the field, was covered with thick, succulent grass in three or four days. There were so many bees that all of them could not accommodate in the hollows of trees and therefore swarmed right in the ground. It happened that from under the feet of a passer-by, streams of excellent honey were sprayed. Along the entire coast of the Dniester, delicious wild grapes grew without any supervision, native apricots and peaches ripened.

Our land seemed especially sweet to the Turkish sultans and neighboring Polish landowners. They rushed here with all their might, set up their lands here, wanted to conquer the Ukrainian people with fire and sword.

Lazarev said that only a hundred years ago there was a transit prison in our Old Fortress. In the walls of the destroyed white building in the fortress courtyard, gratings are still preserved. Behind them sat the prisoners who, by order of the tsar, were sent to Siberia to hard labor. The famous Ukrainian rebel Ustin Karmelyuk languished in the Papal Tower under Tsar Nicholas the First. With his brothers-in-arms, he caught the gentlemen, police officers, priests, bishops passing through the Kalinovsky forest, took money from them, horses and distributed everything that was taken to the poor peasants. The peasants hid Karmelyuk in the cellars, in the heaps on the field, and none of the tsar's detectives for a long time could catch the brave rebel. He escaped from distant penal servitude three times. They beat him, but how they beat him! Karmelyuk's back withstood more than four thousand blows with gauntlets and batogs. Hungry, wounded, every time he escaped from prison and through the frosty deep taiga, for weeks without seeing a piece of stale bread, he made his way to his homeland - to Podolia.

“Along the roads to Siberia and back alone,” Valerian Dmitrievich told us, “Karmelyuk walked about twenty thousand miles on foot. It was not for nothing that the peasants believed that Karmelyuk would freely swim across any sea, that he could break any shackles, that there was no prison in the world from which he could not leave.