Guerrilla warfare: historical significance. The partisan movement is “the cudgel of the people’s war. Partisan detachments during the Patriotic War of 1812

Read also

Patriotic War of 1812. Guerrilla movement

Introduction

The partisan movement was a vivid expression of the national character of the Patriotic War of 1812. Having broken out after the invasion of Napoleonic troops into Lithuania and Belarus, it developed every day, took on more active forms and became a formidable force.

At first, the partisan movement was spontaneous, consisting of performances of small, scattered partisan detachments, then it captured entire regions. Large detachments began to be created, thousands of national heroes appeared, and talented organizers of the partisan struggle emerged.

Why did the disenfranchised peasantry, mercilessly oppressed by the feudal landowners, rise up to fight against their seemingly “liberator”? Napoleon did not even think about any liberation of the peasants from serfdom or improvement of their powerless situation. If at first promising phrases were uttered about the emancipation of the serfs and there was even talk about the need to issue some kind of proclamation, then this was only a tactical move with the help of which Napoleon hoped to intimidate the landowners.

Napoleon understood that the liberation of Russian serfs would inevitably lead to revolutionary consequences, which is what he feared most. Yes, this did not meet his political goals when joining Russia. According to Napoleon's comrades, it was “important for him to strengthen monarchism in France and it was difficult for him to preach revolution to Russia.”

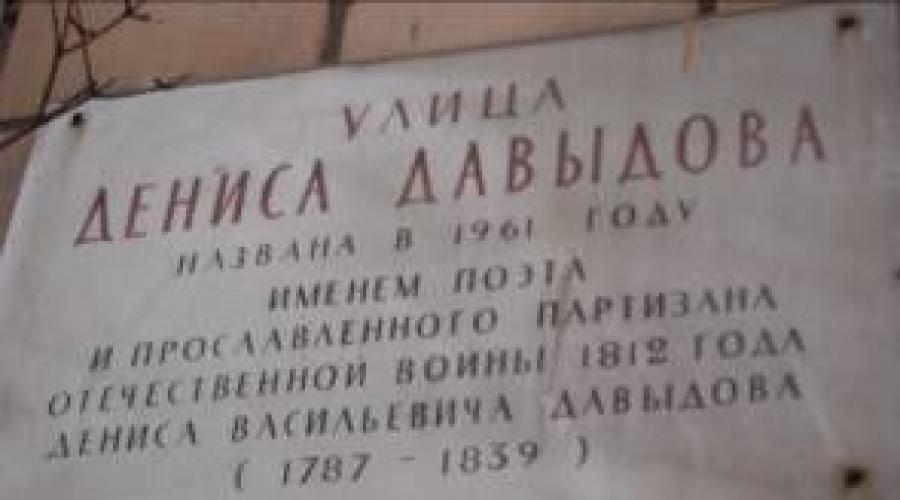

The purpose of the work is to consider Denis Davydov as a hero of the partisan war and a poet. Work objectives to consider:

Reasons for the emergence of partisan movements

Partisan movement of D. Davydov

Denis Davydov as a poet

1. Reasons for the emergence of partisan detachments

The beginning of the partisan movement in 1812 is associated with the manifesto of Alexander I of July 6, 1812, which supposedly allowed the peasants to take up arms and actively participate in the struggle. In reality the situation was different. Without waiting for orders from their superiors, when the French approached, residents fled into the forests and swamps, often leaving their homes to be looted and burned.

The peasants quickly realized that the invasion of the French conquerors put them in an even more difficult and humiliating position than they had been in before. The peasants also associated the fight against foreign enslavers with the hope of liberating them from serfdom.

At the beginning of the war, the struggle of the peasants acquired the character of mass abandonment of villages and villages and the movement of the population to forests and areas remote from military operations. And although this was still a passive form of struggle, it created serious difficulties for the Napoleonic army. The French troops, having a limited supply of food and fodder, quickly began to experience an acute shortage of them. This immediately affected the deterioration of the general condition of the army: horses began to die, soldiers began to starve, and looting intensified. Even before Vilna, more than 10 thousand horses died.

The actions of peasant partisan detachments were both defensive and offensive in nature. In the area of Vitebsk, Orsha, and Mogilev, detachments of peasant partisans made frequent day and night raids on enemy convoys, destroyed their foragers, and captured French soldiers. Napoleon was forced to remind the chief of staff Berthier more and more often about the large losses in people and strictly ordered the allocation of an increasing number of troops to cover the foragers.

2. Partisan detachment of Denis Davydov

Along with the formation of large peasant partisan detachments and their activities, army partisan detachments played a major role in the war. The first army partisan detachment was created on the initiative of M. B. Barclay de Tolly.

Its commander was General F.F. Vintsengerode, who led the united Kazan Dragoon, Stavropol, Kalmyk and three Cossack regiments, which began to operate in the area of Dukhovshchina.

After the invasion of Napoleonic troops, peasants began to go into the forests, partisan heroes began to create peasant detachments and attack individual French teams. The struggle of the partisan detachments unfolded with particular force after the fall of Smolensk and Moscow. The partisan troops boldly attacked the enemy and captured the French. Kutuzov allocated a detachment to operate behind enemy lines under the leadership of D. Davydov, whose detachment disrupted the enemy’s communication routes, freed prisoners, and inspired the local population to fight the invaders. Following the example of Denisov’s detachment, by October 1812, 36 Cossacks, 7 cavalry, 5 infantry regiments, 3 battalions of rangers and other units, including artillery, were operating.

Residents of the Roslavl district created several mounted and foot partisan detachments, arming them with pikes, sabers and guns. They not only defended their district from the enemy, but also attacked the marauders making their way into the neighboring Elny district. Many partisan detachments operated in Yukhnovsky district. Having organized defense along the Ugra River, they blocked the enemy’s path in Kaluga and provided significant assistance to the army partisans of Denis Davydov’s detachment.

The detachment of Denis Davydov was a real threat for the French. This detachment arose on the initiative of Davydov himself, lieutenant colonel, commander of the Akhtyrsky Hussar Regiment. Together with his hussars, he retreated as part of Bagration’s army to Borodin. A passionate desire to bring even greater benefit in the fight against the invaders prompted D. Davydov to “ask for a separate detachment.” He was strengthened in this intention by Lieutenant M.F. Orlov, who was sent to Smolensk to clarify the fate of the seriously wounded General P.A. Tuchkov, who was captured. After returning from Smolensk, Orlov spoke about the unrest and poor rear protection in the French army.

While driving through the territory occupied by Napoleonic troops, he realized how vulnerable the French food warehouses, guarded by small detachments, were. At the same time, he saw how difficult it was for flying peasant detachments to fight without a coordinated plan of action. According to Orlov, small army detachments sent behind enemy lines could inflict great damage on him and help the actions of the partisans.

D. Davydov asked General P.I. Bagration to allow him to organize a partisan detachment to operate behind enemy lines. For a “test,” Kutuzov allowed Davydov to take 50 hussars and -1280 Cossacks and go to Medynen and Yukhnov. Having received a detachment at his disposal, Davydov began bold raids behind enemy lines. In the very first skirmishes near Tsarev - Zaimishch, Slavkoy, he achieved success: he defeated several French detachments and captured a convoy with ammunition.

In the fall of 1812, partisan detachments surrounded the French army in a continuous mobile ring.

A detachment of Lieutenant Colonel Davydov, reinforced by two Cossack regiments, operated between Smolensk and Gzhatsk. A detachment of General I.S. Dorokhov operated from Gzhatsk to Mozhaisk. Captain A.S. Figner with his flying detachment attacked the French on the road from Mozhaisk to Moscow.

In the area of Mozhaisk and to the south, a detachment of Colonel I.M. Vadbolsky operated as part of the Mariupol Hussar Regiment and 500 Cossacks. Between Borovsk and Moscow, the roads were controlled by a detachment of captain A. N. Seslavin. Colonel N.D. Kudashiv was sent to the Serpukhov road with two Cossack regiments. On the Ryazan road there was a detachment of Colonel I. E. Efremov. From the north, Moscow was blocked by a large detachment of F.F. Wintsengerode, who, separating small detachments from himself to Volokolamsk, on the Yaroslavl and Dmitrov roads, blocked access for Napoleon’s troops to the northern regions of the Moscow region.

The partisan detachments operated in difficult conditions. At first there were many difficulties. Even residents of villages and villages at first treated the partisans with great distrust, often mistaking them for enemy soldiers. Often the hussars had to dress in peasant caftans and grow beards.

The partisan detachments did not stand in one place, they were constantly on the move, and no one except the commander knew in advance when and where the detachment would go. The partisans' actions were sudden and swift. To swoop down out of the blue and quickly hide became the main rule of the partisans.

The detachments attacked individual teams, foragers, transports, took away weapons and distributed them to the peasants, and took dozens and hundreds of prisoners.

Davydov’s detachment on the evening of September 3, 1812 went to Tsarev-Zamishch. Not reaching 6 versts to the village, Davydov sent reconnaissance there, which established that there was a large French convoy with shells, guarded by 250 horsemen. The detachment at the edge of the forest was discovered by French foragers, who rushed to Tsarevo-Zamishche to warn their own. But Davydov did not let them do this. The detachment rushed in pursuit of the foragers and almost burst into the village together with them. The convoy and its guards were taken by surprise, and an attempt by a small group of French to resist was quickly suppressed. 130 soldiers, 2 officers, 10 carts with food and fodder ended up in the hands of the partisans.

3. Denis Davydov as a poet

Denis Davydov was a wonderful romantic poet. He belonged to the genre of romanticism.

It should be noted that almost always in human history, a nation that has been subjected to aggression creates a powerful layer of patriotic literature. This was the case, for example, during the Mongol-Tatar invasion of Rus'. And only some time later, having recovered from the blow, having overcome pain and hatred, thinkers and poets think about all the horrors of the war for both sides, about its cruelty and senselessness. This is very clearly reflected in the poems of Denis Davydov.

In my opinion, Davydov’s poem is one of the outbursts of patriotic militancy caused by the invasion of the enemy.

What did this unshakable strength of the Russians consist of?

This strength was made up of patriotism not in words, but in deeds of the best people from the nobility, poets and simply the Russian people.

This strength consisted of the heroism of the soldiers and best officers of the Russian army.

This invincible force was formed from the heroism and patriotism of Muscovites who leave their hometown, no matter how sorry they are to leave their property to destruction.

The invincible strength of the Russians consisted of the actions of partisan detachments. This is Denisov’s detachment, where the most needed person is Tikhon Shcherbaty, the people’s avenger. Partisan detachments destroyed Napoleonic army piece by piece.

So, Denis Davydov in his works depicts the war of 1812 as a people’s war, a Patriotic War, when the entire people rose to defend the Motherland. And the poet did this with enormous artistic power, creating a grandiose poem - an epic that has no equal in the world.

The work of Denis Davydov can be illustrated as follows:

Dream

Who could cheer you up so much, my friend?

You can hardly speak from laughter.

What joys delight your mind, Or do they lend you money without a bill?

Or a happy waist has come to you

And did the pair of trantels take the endurance test?

What happened to you that you don’t answer?

Ay! give me a rest, you know nothing!

I'm really beside myself, I almost went crazy:

Today I found Petersburg completely different!

I thought that the whole world had completely changed:

Imagine - Nn paid off his debt;

There are no more pedants and fools to be seen,

And even Zoey and Sov got smarter!

There is no courage in the unfortunate rhymers of old,

And our dear Marin does not stain papers,

And, deepening into the service, he works with his head:

How, when starting a platoon, shout at the right time: stop!

But what I was more delighted by was:

Koev, who pretended to be Lycurgus,

For our happiness he wrote laws for us,

Suddenly, fortunately for us, he stopped writing them.

A happy change has appeared in everything,

Theft, robbery, treason have disappeared,

No more complaints or grievances are visible,

Well, in a word, the city took on a completely disgusting appearance.

Nature gave beauty to the ugly,

And Lll himself stopped looking askance at nature,

Bna's nose has become shorter,

And Ditch scared people with his beauty,

Yes, I, who myself, from the beginning of my century,

It was a stretch to bear the name of a person,

I look, I’m happy, I don’t recognize myself:

Where the beauty comes from, where the growth comes from - I look;

Every word is bon mot, every look is passion,

I’m amazed how I manage to change my intrigues!

Suddenly, oh the wrath of heaven! suddenly fate struck me:

Among the blissful days Andryushka woke up,

And everything I saw, what I had so much fun with -

I saw everything in a dream, and lost everything in the dream.

Burtsov

In a smoky field, on a bivouac

By the blazing fires

In the beneficial arak

I see the savior of people.

Gather in a circle

Orthodox is all to blame!

Give me the golden tub,

Where fun lives!

Pour out vast cups

In the noise of joyful speeches,

How our ancestors drank

Among spears and swords.

Burtsev, you are a hussar of hussars!

You're on a crazy horse

The cruelest of frenzy

And a rider in war!

Let's hit cup and cup together!

Today it’s still too late to drink;

Tomorrow the trumpets will sound,

Tomorrow there will be thunder.

Let's drink and swear

That we indulge in a curse,

If we ever

Let's give way, turn pale,

Let's pity our breasts

And in misfortune we become timid;

If we ever give

Left side on the flank,

Or we'll rein in the horse,

Or a cute little cheat

Let's give our hearts for free!

Let it not be with a saber strike

My life will be cut short!

Let me be a general

How many I have seen!

Let among the bloody battles

I will be pale, fearful,

And in the meeting of heroes

Sharp, brave, talkative!

Let my mustache, the beauty of nature,

Black-brown, in curls,

Will be cut off in youth

And it will disappear like dust!

Let fortune be for vexation,

To multiply all troubles,

He will give me a rank for shift parades

And "Georgia" for the advice!

Let... But chu! This is not the time to walk!

To the horses, brother, and your foot in the stirrup,

Saber out - and cut!

Here is another feast God gives us,

And noisier and more fun...

Come on, put your shako on one side,

And - hurray! Happy day!

V. A. Zhukovsky

Zhukovsky, dear friend! Debt is rewarded by payment:

I read the poems you dedicated to me;

Now read mine, you are smoked in the bivouac

And sprinkled with wine!

It's been a long time since I chatted with either the muse or you,

Did I care about my feet?..

.........................................

But even in the thunderstorms of war, still on the battlefield,

When the Russian camp went out,

I greeted you with a huge glass

An impudent partisan wandering in the steppes!

Conclusion

It was not by chance that the War of 1812 received the name Patriotic War. The popular character of this war was most clearly manifested in the partisan movement, which played a strategic role in the victory of Russia. Responding to accusations of “war not according to the rules,” Kutuzov said that these were the feelings of the people. Responding to a letter from Marshal Bertha, he wrote on October 8, 1818: “It is difficult to stop a people embittered by everything they have seen; a people who for so many years have not known war on their territory; a people ready to sacrifice themselves for their Motherland... ". Activities aimed at attracting the masses to active participation in the war were based on the interests of Russia, correctly reflected the objective conditions of the war and took into account the broad opportunities that emerged in the national liberation war.

During the preparation for the counteroffensive, the combined forces of the army, militia and partisans constrained the actions of Napoleonic troops, inflicted damage on enemy personnel, and destroyed military property. The Smolenskaya-10 road, which remained the only guarded postal route leading from Moscow to the west, was constantly subject to partisan raids. They intercepted French correspondence, especially valuable ones were delivered to the main apartment of the Russian army.

The partisan actions of the peasants were highly appreciated by the Russian command. “The peasants,” wrote Kutuzov, “from the villages adjacent to the theater of war inflict the greatest harm on the enemy... They kill the enemies in large numbers, and deliver those captured to the army.” The peasants of the Kaluga province alone killed and captured more than 6 thousand French.

And yet, one of the most heroic actions of 1812 remains the feat of Denis Davydov and his squad.

Bibliography

Zhilin P. A. The death of Napoleonic army in Russia. M., 1974. History of France, vol. 2. M., 2001.-687p.

History of Russia 1861-1917, ed. V. G. Tyukavkina, Moscow: INFRA, 2002.-569 p.

Orlik O.V. Thunderstorm of the twelfth year.... M.: INFRA, 2003.-429p.

Platonov S.F. Textbook of Russian history for secondary school M., 2004.-735p.

Reader on the History of Russia 1861-1917, ed. V. G. Tyukavkina - Moscow: DROFA, 2000.-644 p.

Partisan movement in the Patriotic War of 1812.

Abstract on the history of an 11th grade student, 505 school Elena Afitova

Partisan movement in the War of 1812

Guerrilla movement, the armed struggle of the masses for the freedom and independence of their country or social transformation, waged in territory occupied by the enemy (controlled by the reactionary regime). Units of regular troops operating behind enemy lines can also take part in the Partisan movement.

The partisan movement in the Patriotic War of 1812, the armed struggle of the people, mainly peasants of Russia, and detachments of the Russian army against the French invaders in the rear of Napoleonic troops and on their communications. The partisan movement began in Lithuania and Belarus after the retreat of the Russian army. At first, the movement was expressed in the refusal to supply the French army with forage and food, the massive destruction of stocks of these types of supplies, which created serious difficulties for Napoleonic troops. With the entry of the region into Smolensk, and then into Moscow and Kaluga provinces, the partisan movement assumed a particularly wide scope. At the end of July-August, in Gzhatsky, Belsky, Sychevsky and other districts, peasants united into foot and horse partisan detachments, armed with pikes, sabers and guns, attacked separate groups of enemy soldiers, foragers and convoys, and disrupted the communications of the French army. The partisans were a serious fighting force. The number of individual detachments reached 3-6 thousand people. The partisan detachments of G.M. Kurin, S. Emelyanov, V. Polovtsev, V. Kozhina and others became widely known. Tsarist law treated the Partisan movement with distrust. But in an atmosphere of patriotic upsurge, some landowners and progressive-minded generals (P.I. Bagration, M.B. Barclay de Tolly, A.P. Ermolov and others). The commander-in-chief of the Russian army, Field Marshal M.I., attached especially great importance to the people's partisan struggle. Kutuzov. He saw in it a tremendous force, capable of causing significant damage to the enemy, and he contributed in every possible way to the organization of new detachments, giving instructions on their weapons and instructions on guerrilla warfare tactics. After leaving Moscow, the front of the Partisan movement was significantly expanded, and Kutuzov, in his plans, gave it an organized character. This was greatly facilitated by the formation of special detachments from regular troops operating by guerrilla methods. The first such detachment, numbering 130 people, was created at the end of August on the initiative of Lieutenant Colonel D.V. Davydova. In September, 36 Cossack, 7 cavalry and 5 infantry regiments, 5 squadrons and 3 battalions operated as part of the army partisan detachments. The detachments were commanded by generals and officers I.S. Dorokhov, M.A. Fonvizin and others. Many peasant detachments that arose spontaneously later joined the army or closely interacted with them. Individual detachments of the people's formation were also involved in partisan actions. militia. The partisan movement reached its widest scope in the Moscow, Smolensk and Kaluga provinces. Acting on the communications of the French army, partisan detachments exterminated enemy foragers, captured convoys, and provided the Russian command with valuable information about the ship. Under these conditions, Kutuzov set broader tasks for the Partisan Movement to interact with the army and strike at individual garrisons and reserves of the pr-ka. Thus, on September 28 (October 10), by order of Kutuzov, General Dorokhov’s detachment, with the support of peasant detachments, captured the city of Vereya. As a result of the battle, the French lost about 700 people killed and wounded. In total, in 5 weeks after the Battle of Borodino, 1812 pr-k lost over 30 thousand people as a result of partisan attacks. Along the entire retreat route of the French army, partisan detachments assisted Russian troops in pursuing and destroying the enemy, attacking their convoys and destroying individual detachments. In general, the Partisan movement provided great assistance to the Russian army in defeating Napoleonic troops and expelling them from Russia.

Causes of guerrilla warfare

The partisan movement was a vivid expression of the national character of the Patriotic War of 1812. Having broken out after the invasion of Napoleonic troops into Lithuania and Belarus, it developed every day, took on more active forms and became a formidable force.

At first, the partisan movement was spontaneous, consisting of performances of small, scattered partisan detachments, then it captured entire areas. Large detachments began to be created, thousands of national heroes appeared, and talented organizers of the partisan struggle emerged.

Why did the disenfranchised peasantry, mercilessly oppressed by the feudal landowners, rise up to fight against their seemingly “liberator”? Napoleon did not even think about any liberation of the peasants from serfdom or improvement of their powerless situation. If at first promising phrases were uttered about the emancipation of the serfs and there was even talk about the need to issue some kind of proclamation, then this was only a tactical move with the help of which Napoleon hoped to intimidate the landowners.

Napoleon understood that the liberation of Russian serfs would inevitably lead to revolutionary consequences, which is what he feared most. Yes, this did not meet his political goals when joining Russia. According to Napoleon's comrades, it was “important for him to strengthen monarchism in France and it was difficult for him to preach revolution in Russia.”

The very first orders of the administration established by Napoleon in the occupied regions were directed against the serfs and in defense of the feudal landowners. The temporary Lithuanian “government”, subordinate to the Napoleonic governor, in one of the very first resolutions obliged all peasants and rural residents in general to unquestioningly obey the landowners, to continue to perform all work and duties, and those who would evade were to be severely punished, attracting for this purpose , if circumstances require it, military force.

Sometimes the beginning of the partisan movement in 1812 is associated with the manifesto of Alexander I of July 6, 1812, which supposedly allowed the peasants to take up arms and actively participate in the struggle. In reality the situation was different. Without waiting for orders from their superiors, when the French approached, residents fled into the forests and swamps, often leaving their homes to be looted and burned.

The peasants quickly realized that the invasion of the French conquerors put them in an even more difficult and humiliating position than they had been in before. The peasants also associated the fight against foreign enslavers with the hope of liberating them from serfdom.

Peasants' War

At the beginning of the war, the struggle of the peasants acquired the character of mass abandonment of villages and villages and the movement of the population to forests and areas remote from military operations. And although this was still a passive form of struggle, it created serious difficulties for the Napoleonic army. The French troops, having a limited supply of food and fodder, quickly began to experience an acute shortage of them. This immediately affected the deterioration of the general condition of the army: horses began to die, soldiers began to starve, and looting intensified. Even before Vilna, more than 10 thousand horses died.

French foragers sent to villages for food faced more than just passive resistance. After the war, one French general wrote in his memoirs: “The army could only eat what the marauders, organized in entire detachments, got; Cossacks and peasants killed many of our people every day who dared to go in search.” In the villages there were clashes, including shooting, between French soldiers sent for food and peasants. Such clashes occurred quite often. It was in such battles that the first peasant partisan detachments were created, and a more active form of people's resistance arose - partisan warfare.

The actions of peasant partisan detachments were both defensive and offensive in nature. In the area of Vitebsk, Orsha, and Mogilev, detachments of peasant partisans made frequent day and night raids on enemy convoys, destroyed their foragers, and captured French soldiers. Napoleon was forced to remind the chief of staff Berthier more and more often about the large losses in people and strictly ordered the allocation of an increasing number of troops to cover the foragers.

The partisan struggle of the peasants acquired its widest scope in August in the Smolensk province. It began in the Krasnensky, Porechsky districts, and then in the Belsky, Sychevsky, Roslavl, Gzhatsky and Vyazemsky districts. At first, the peasants were afraid to arm themselves, they were afraid that they would later be brought to justice.

In the city of Bely and Belsky district, partisan detachments attacked French parties making their way towards them, destroyed them or took them prisoner. The leaders of the Sychev partisans, police officer Boguslavskaya and retired major Emelyanov, armed their detachments with guns taken from the French and established proper order and discipline. Sychevsky partisans attacked the enemy 15 times in two weeks (from August 18 to September 1). During this time, they killed 572 soldiers and captured 325 people.

Residents of the Roslavl district created several mounted and foot partisan detachments, arming them with pikes, sabers and guns. They not only defended their district from the enemy, but also attacked the marauders making their way into the neighboring Elny district. Many partisan detachments operated in Yukhnovsky district. Having organized defense along the Ugra River, they blocked the enemy’s path in Kaluga and provided significant assistance to the army partisans of Denis Davydov’s detachment.

The largest Gzhat partisan detachment operated successfully. Its organizer was a soldier of the Elizavetgrad regiment Fedor Potopov (Samus). Wounded in one of the rearguard battles after Smolensk, Samus found himself behind enemy lines and, after recovery, immediately began organizing a partisan detachment, the number of which soon reached 2 thousand people (according to other sources, 3 thousand). His striking force was a cavalry group of 200 people, armed and dressed in armor of French cuirassiers. The Samusya detachment had its own organization and strict discipline was established in it. Samus introduced a system of warning the population about the approach of the enemy through the ringing of bells and other conventional signs. Often in such cases, the villages became empty; according to another conventional sign, the peasants returned from the forests. Lighthouses and the ringing of bells of various sizes communicated when and in what numbers, on horseback or on foot, one should go into battle. In one of the battles, members of this detachment managed to capture a cannon. Samusya's detachment caused significant damage to the French troops. In the Smolensk province he destroyed about 3 thousand enemy soldiers.

Another partisan detachment, created from peasants, was also active in the Gzhatsk district, headed by Ermolai Chetvertak (Chetvertakov), a private in the Kyiv Dragoon Regiment. He was wounded in the battle near Tsarevo-Zamishche and taken prisoner, but he managed to escape. From the peasants of the villages of Basmany and Zadnovo, he organized a partisan detachment, which initially numbered 40 people, but soon grew to 300 people. Chetvertakov’s detachment began not only to protect villages from marauders, but to attack the enemy, inflicting heavy losses on him. In Sychevsky district, partisan Vasilisa Kozhina became famous for her brave actions.

There are many facts and evidence that the partisan peasant detachments of Gzhatsk and other areas located along the main road to Moscow caused great trouble to the French troops.

The actions of partisan detachments became especially intensified during the stay of the Russian army in Tarutino. At this time, they widely deployed the front of the struggle in the Smolensk, Moscow, Ryazan and Kaluga provinces. Not a day passed without the partisans, in one place or another, raiding a moving enemy convoy with food, or defeating a French detachment, or, finally, suddenly attacking the French soldiers and officers stationed in the village.

In Zvenigorod district, peasant partisan detachments destroyed and captured more than 2 thousand French soldiers. Here the detachments became famous, the leaders of which were the volost mayor Ivan Andreev and the centenarian Pavel Ivanov. In Volokolamsk district, partisan detachments were led by retired non-commissioned officer Novikov and private Nemchinov, volost mayor Mikhail Fedorov, peasants Akim Fedorov, Philip Mikhailov, Kuzma Kuzmin and Gerasim Semenov. In the Bronnitsky district of the Moscow province, peasant partisan detachments united up to 2 thousand people. They repeatedly attacked large enemy parties and defeated them. History has preserved for us the names of the most distinguished peasants - partisans from the Bronnitsy district: Mikhail Andreev, Vasily Kirillov, Sidor Timofeev, Yakov Kondratyev, Vladimir Afanasyev.

The largest peasant partisan detachment in the Moscow region was the Bogorodsk partisan detachment. It numbered about 6 thousand people in its ranks. The talented leader of this detachment was the serf Gerasim Kurin. His detachment and other smaller detachments not only reliably defended the entire Bogorodskaya district from the penetration of French marauders, but also entered into armed struggle with enemy troops. So, on October 1, partisans under the leadership of Gerasim Kurin and Yegor Stulov entered into battle with two enemy squadrons and, acting skillfully, defeated them.

Peasant partisan detachments received assistance from the commander-in-chief of the Russian army, M. I. Kutuzov. With satisfaction and pride, Kutuzov wrote to St. Petersburg:

The peasants, burning with love for the Motherland, organize militias among themselves... Every day they come to the Main Apartment, convincingly asking for firearms and ammunition for protection from enemies. The requests of these respectable peasants, true sons of the fatherland, are satisfied as far as possible and they are supplied with rifles, pistols and cartridges."

During the preparation for the counteroffensive, the combined forces of the army, militia and partisans constrained the actions of Napoleonic troops, inflicted damage on enemy personnel, and destroyed military property. The Smolensk road, which remained the only guarded postal route leading from Moscow to the west, was constantly subject to partisan raids. They intercepted French correspondence, especially valuable ones were delivered to the main apartment of the Russian army.

The partisan actions of the peasants were highly appreciated by the Russian command. “The peasants,” wrote Kutuzov, “from the villages adjacent to the theater of war inflict the greatest harm on the enemy... They kill the enemies in large numbers, and deliver those captured to the army.” The peasants of the Kaluga province alone killed and captured more than 6 thousand French. During the capture of Vereya, a peasant partisan detachment (up to 1 thousand people), led by priest Ivan Skobeev, distinguished itself.

In addition to direct military operations, it should be noted the participation of militias and peasants in reconnaissance.

Army partisan units

Along with the formation of large peasant partisan detachments and their activities, army partisan detachments played a major role in the war.

The first army partisan detachment was created on the initiative of M. B. Barclay de Tolly. Its commander was General F.F. Wintsengerode, who led the united Kazan Dragoon, Stavropol, Kalmyk and three Cossack regiments, which began to operate in the area of Dukhovshchina.

The detachment of Denis Davydov was a real threat for the French. This detachment arose on the initiative of Davydov himself, lieutenant colonel, commander of the Akhtyrsky Hussar Regiment. Together with his hussars, he retreated as part of Bagration’s army to Borodin. A passionate desire to bring even greater benefit in the fight against the invaders prompted D. Davydov to “ask for a separate detachment.” He was strengthened in this intention by Lieutenant M.F. Orlov, who was sent to Smolensk to clarify the fate of the seriously wounded General P.A. Tuchkov, who was captured. After returning from Smolensk, Orlov spoke about the unrest and poor rear protection in the French army.

While driving through the territory occupied by Napoleonic troops, he realized how vulnerable the French food warehouses, guarded by small detachments, were. At the same time, he saw how difficult it was for flying peasant detachments to fight without a coordinated plan of action. According to Orlov, small army detachments sent behind enemy lines could inflict great damage on him and help the actions of the partisans.

D. Davydov asked General P.I. Bagration to allow him to organize a partisan detachment to operate behind enemy lines. For a “test,” Kutuzov allowed Davydov to take 50 hussars and 80 Cossacks and go to Medynen and Yukhnov. Having received a detachment at his disposal, Davydov began bold raids behind enemy lines. In the very first skirmishes near Tsarev - Zaimishch, Slavkoy, he achieved success: he defeated several French detachments and captured a convoy with ammunition.

In the fall of 1812, partisan detachments surrounded the French army in a continuous mobile ring. A detachment of Lieutenant Colonel Davydov, reinforced by two Cossack regiments, operated between Smolensk and Gzhatsk. A detachment of General I.S. Dorokhov operated from Gzhatsk to Mozhaisk. Captain A.S. Figner with his flying detachment attacked the French on the road from Mozhaisk to Moscow. In the Mozhaisk region and to the south, a detachment of Colonel I.M. Vadbolsky operated as part of the Mariupol Hussar Regiment and 500 Cossacks. Between Borovsk and Moscow, the roads were controlled by a detachment of captain A. N. Seslavin. Colonel N.D. Kudashiv was sent to the Serpukhov road with two Cossack regiments. On the Ryazan road there was a detachment of Colonel I. E. Efremov. From the north, Moscow was blocked by a large detachment of F.F. Wintsengerode, who, separating small detachments from himself to Volokolamsk, on the Yaroslavl and Dmitrov roads, blocked access for Napoleon’s troops to the northern regions of the Moscow region.

The main task of the partisan detachments was formulated by Kutuzov: “Since now the autumn time is coming, through which the movement of a large army becomes completely difficult, then I decided, avoiding a general battle, to wage a small war, because the separated forces of the enemy and his oversight give me more ways to exterminate him , and for this purpose, being now 50 versts from Moscow with the main forces, I am giving up important units in the direction of Mozhaisk, Vyazma and Smolensk."

Army partisan detachments were created mainly from Cossack troops and were unequal in size: from 50 to 500 people. They were tasked with bold and sudden actions behind enemy lines to destroy his manpower, strike at garrisons and suitable reserves, disable transport, deprive the enemy of the opportunity to obtain food and fodder, monitor the movement of troops and report this to the General Staff Russian army. The commanders of the partisan detachments were indicated the main direction of action, and were informed of the areas of operation of neighboring detachments in the event of joint operations.

The partisan detachments operated in difficult conditions. At first there were many difficulties. Even residents of villages and villages at first treated the partisans with great distrust, often mistaking them for enemy soldiers. Often the hussars had to dress in peasant caftans and grow beards.

The partisan detachments did not stand in one place, they were constantly on the move, and no one except the commander knew in advance when and where the detachment would go. The partisans' actions were sudden and swift. To swoop down out of the blue and quickly hide became the main rule of the partisans.

The detachments attacked individual teams, foragers, transports, took away weapons and distributed them to the peasants, and took dozens and hundreds of prisoners.

Davydov’s detachment on the evening of September 3, 1812 went to Tsarev-Zamishch. Not reaching 6 versts to the village, Davydov sent reconnaissance there, which established that there was a large French convoy with shells, guarded by 250 horsemen. The detachment at the edge of the forest was discovered by French foragers, who rushed to Tsarevo-Zamishche to warn their own. But Davydov did not let them do this. The detachment rushed in pursuit of the foragers and almost burst into the village together with them. The convoy and its guards were taken by surprise, and an attempt by a small group of French to resist was quickly suppressed. 130 soldiers, 2 officers, 10 carts with food and fodder ended up in the hands of the partisans.

Sometimes, knowing the location of the enemy in advance, the partisans launched a surprise raid. Thus, General Vintsengerod, having established that in the village of Sokolov there was an outpost of two cavalry squadrons and three infantry companies, allocated 100 Cossacks from his detachment, who quickly burst into the village, destroyed more than 120 people and captured 3 officers, 15 non-commissioned officers , 83 soldiers.

Colonel Kudashev's detachment, having established that there were about 2,500 French soldiers and officers in the village of Nikolskoye, suddenly attacked the enemy, more than 100 people and took 200 prisoners.

Most often, partisan detachments ambushed and attacked enemy transport on the way, captured couriers, and freed Russian prisoners. The partisans of General Dorokhov's detachment, operating along the Mozhaisk road, on September 12 captured two couriers with dispatches, burned 20 boxes of shells and captured 200 people (including 5 officers). On September 16, Colonel Efremov’s detachment, encountering an enemy column heading towards Podolsk, attacked it and captured more than 500 people.

Captain Figner's detachment, which was always close to the enemy troops, in a short time destroyed almost all the food in the vicinity of Moscow, blew up an artillery park on the Mozhaisk road, destroyed 6 guns, killed up to 400 people, captured a colonel, 4 officers and 58 soldiers.

Later, the partisan detachments were consolidated into three large parties. One of them, under the command of Major General Dorokhov, consisting of five infantry battalions, four cavalry squadrons, two Cossack regiments with eight guns, took the city of Vereya on September 28, 1812, destroying part of the French garrison.

Conclusion

It was not by chance that the War of 1812 received the name Patriotic War. The popular character of this war was most clearly manifested in the partisan movement, which played a strategic role in the victory of Russia. Responding to accusations of “war not according to the rules,” Kutuzov said that these were the feelings of the people. Responding to a letter from Marshal Berthier, he wrote on October 8, 1818: “It is difficult to stop a people embittered by everything they have seen; a people who for so many years have not known war on their territory; a people ready to sacrifice themselves for their Motherland... ".

Activities aimed at attracting the masses to active participation in the war were based on the interests of Russia, correctly reflected the objective conditions of the war and took into account the broad opportunities that emerged in the national liberation war.

Bibliography

P.A. Zhilin The death of Napoleonic army in Russia. M., 1968.

History of France, vol.2. M., 1973.

O.V. Orlik "The Thunderstorm of the Twelfth Year...". M., 1987.

The partisan movement in the Patriotic War of 1812 significantly influenced the outcome of the campaign. The French met fierce resistance from the local population. Demoralized, deprived of the opportunity to replenish their food supplies, Napoleon's tattered and frozen army was brutally beaten by Russian flying and peasant partisan detachments.

Squadrons of flying hussars and detachments of peasants

The greatly extended Napoleonic army, pursuing the retreating Russian troops, quickly began to represent a convenient target for partisan attacks - the French often found themselves far removed from the main forces. The command of the Russian army decided to create mobile units to carry out sabotage behind enemy lines and deprive them of food and fodder.

During the Patriotic War, there were two main types of such detachments: flying squadrons of army cavalrymen and Cossacks, formed by order of Commander-in-Chief Mikhail Kutuzov, and groups of partisan peasants, uniting spontaneously, without army leadership. In addition to actual acts of sabotage, flying detachments also engaged in reconnaissance. Peasant self-defense forces mainly repelled the enemy from their villages.

Denis Davydov was mistaken for a Frenchman

Denis Davydov is the most famous commander of a partisan detachment in the Patriotic War of 1812. He himself drew up a plan of action for mobile partisan formations against the Napoleonic army and proposed it to Pyotr Ivanovich Bagration. The plan was simple: to annoy the enemy in his rear, capture or destroy enemy warehouses with food and fodder, and beat small groups of the enemy.

Under the command of Davydov there were over one and a half hundred hussars and Cossacks. Already in September 1812, in the area of the Smolensk village of Tsarevo-Zaymishche, they captured a French caravan of three dozen carts. Davydov’s cavalrymen killed more than 100 Frenchmen from the accompanying detachment, and captured another 100. This operation was followed by others, also successful.

Davydov and his team did not immediately find support from the local population: at first the peasants mistook them for the French. The commander of the flying detachment even had to put on a peasant's caftan, hang an icon of St. Nicholas on his chest, grow a beard and switch to the language of the Russian common people - otherwise the peasants would not believe him.

Over time, Denis Davydov’s detachment increased to 300 people. The cavalrymen attacked French units, which sometimes had a fivefold numerical superiority, and defeated them, taking convoys and freeing prisoners, and sometimes even captured enemy artillery.

After leaving Moscow, on the orders of Kutuzov, flying partisan detachments were created everywhere. These were mainly Cossack formations, each numbering up to 500 sabers. At the end of September, Major General Ivan Dorokhov, who commanded such a formation, captured the town of Vereya near Moscow. United partisan groups could resist large military formations of Napoleon's army. Thus, at the end of October, during a battle in the area of the Smolensk village of Lyakhovo, four partisan detachments completely defeated the more than one and a half thousand brigade of General Jean-Pierre Augereau, capturing him himself. For the French, this defeat turned out to be a terrible blow. This success, on the contrary, encouraged the Russian troops and set them up for further victories.

Peasant initiative

A significant contribution to the destruction and exhaustion of French units was made by peasants who self-organized into combat detachments. Their partisan units began to form even before Kutuzov’s instructions. While willingly helping flying detachments and units of the regular Russian army with food and fodder, the men at the same time harmed the French everywhere and in every possible way - they exterminated enemy foragers and marauders, and often, when the enemy approached, they themselves burned their houses and went into the forests. Fierce local resistance intensified as the demoralized French army increasingly turned into a crowd of robbers and marauders.

One of these detachments was assembled by dragoons Ermolai Chetvertakov. He taught the peasants how to use captured weapons, organized and successfully carried out many acts of sabotage against the French, capturing dozens of enemy convoys with food and livestock. At one time, Chetvertakov’s unit included up to 4 thousand people. And such cases when peasant partisans, led by career military men and noble landowners, successfully operated in the rear of Napoleonic troops were not isolated.

The text of the work is posted without images and formulas.

The full version of the work is available in the "Work Files" tab in PDF format

The Patriotic War of 1812 was one of the turning points in Russian history, a serious shock for Russian society, which was faced with a number of new problems and phenomena that still require comprehension by modern historians.

One of these phenomena was the People's War, which gave rise to an incredible number of rumors, and then persistent legends.

The history of the Patriotic War of 1812 has been sufficiently studied, but many controversial episodes remain in it, since there are conflicting opinions in assessing this event. The differences begin from the very beginning - with the causes of the war, go through all the battles and personalities and end only with the departure of the French from Russia. The issue of the popular partisan movement is not fully understood until today, which is why this topic will always be relevant.

In historiography, this topic is presented quite fully, however, the opinions of domestic historians about the partisan war itself and its participants, about their role in the Patriotic War of 1812 are extremely ambiguous.

Dzhivelegov A.K. wrote the following: “The peasants participated in the war only after Smolensk, but especially after the surrender of Moscow. If there had been more discipline in the Great Army, normal relations with the peasants would have begun very soon. But the foragers turned into marauders, from whom the peasants “naturally defended themselves, and for defense, precisely for defense and nothing more, peasant detachments were formed... all of them, we repeat, had in mind exclusively self-defense. The People's War of 1812 was nothing more than an optical illusion created by the ideology of the nobility...” (6, p. 219).

Opinion of historian Tarle E.V. was a little more lenient, but in general it was similar to the opinion of the author presented above: “All this led to the fact that the mythical “peasant partisans” began to be attributed to what in reality was carried out by the retreating Russian army. There were classic partisans, but mostly only in the Smolensk province. On the other hand, the peasants were terribly annoyed by endless foreign foragers and marauders. And, naturally, they were actively resisted. And “many peasants fled into the forests when the French army approached, often simply out of fear. And not from some great patriotism” (9, p. 12).

Historian Popov A.I. does not deny the existence of peasant partisan detachments, but believes that it is incorrect to call them “partisans”, that they were more like a militia (8, p. 9). Davydov clearly distinguished between “partisans and villagers.” In the leaflets, partisan detachments are clearly distinguished from “peasants from villages adjacent to the theater of war,” who “arrange militias among themselves”; they record the difference between armed villagers and partisans, between “our detached detachments and zemstvo militias” (8, p. 10). So the accusations by Soviet authors of noble and bourgeois historians that they did not consider the peasants to be partisans are completely groundless, because they were not considered such by their contemporaries.

Modern historian N.A. Troitsky in his article “The Patriotic War of 1812 From Moscow to the Neman” wrote: “Meanwhile, a partisan war, destructive for the French, flared up around Moscow. Peaceful townspeople and villagers of both sexes and all ages, armed with anything - from axes to simple clubs, multiplied the ranks of partisans and militias... The total number of people's militia exceeded 400 thousand people. In the combat zone, almost all peasants capable of carrying weapons became partisans. It was the nationwide rise of the masses who came out in defense of the Fatherland that became the main reason for Russia’s victory in the War of 1812” (11)

In pre-revolutionary historiography there were facts discrediting the actions of the partisans. Some historians called the partisans looters, showing their indecent actions not only towards the French, but also towards ordinary residents. In many works of domestic and foreign historians, the role of the resistance movement of the broad masses, which responded to a foreign invasion with a nationwide war, is clearly downplayed.

Our study presents an analysis of the works of such historians as: Alekseev V.P., Babkin V.I., Beskrovny L.G., Bichkov L.N., Knyazkov S.A., Popov A.I., Tarle E.V. ., Dzhivilegov A.K., Troitsky N.A.

The object of our research is the partisan war of 1812, and the subject of the study is a historical assessment of the partisan movement in the Patriotic War of 1812.

In doing so, we used the following research methods: narrative, hermeneutic, content analysis, historical-comparative, historical-genetic.

Based on all of the above, the purpose of our work is to give a historical assessment of such a phenomenon as the partisan war of 1812.

1. Theoretical analysis of sources and works related to the topic of our research;

2. To identify whether such a phenomenon as the “People's War” took place according to the narrative tradition;

3. Consider the concept of “partisan movement of 1812” and its reasons;

4. Consider the peasant and army partisan detachments of 1812;

5. Conduct their comparative analysis in order to determine the role of peasant and army partisan detachments in achieving victory in the Patriotic War of 1812.

Thus, the structure of our work looks like this:

Introduction

Chapter 1: People's War according to the narrative tradition

Chapter 2: General characteristics and comparative analysis of partisan detachments

Conclusion

Bibliography

Chapter 1. People's War according to the narrative tradition

Modern historians often question the existence of the People's War, believing that such actions of peasants were carried out solely for the purpose of self-defense and that detachments of peasants in no case can be distinguished as separate types of partisans.

In the course of our work, a large number of sources were analyzed, ranging from essays to collections of documents, which allowed us to understand whether such a phenomenon as the “People's War” took place.

Reporting documentation always provides the most reliable evidence, since it lacks subjectivity and clearly traces information that proves certain hypotheses. In it you can find many different facts, such as: the size of the army, the names of the units, actions at various stages of the war, the number of casualties and, in our case, facts about the location, number, methods and motives of peasant partisan detachments. In our case, this documentation includes manifestos, reports, government messages.

1) It all started with the “Manifesto of Alexander I on the collection of the zemstvo militia of July 6, 1812.” In it, the tsar directly calls on the peasants to fight the French troops, believing that a regular army alone will not be enough to win the war (4, p. 14).

2) Typical raids on small detachments of the French can be clearly seen in the report of the Zhizdra district leader of the nobility to the Kaluga civil governor (10, p. 117)

3) From the report of E.I. Vlastova Ya.X. Wittgenstein from the town of Bely “On the actions of peasants against the enemy” from the government report “On the activities of peasant detachments against Napoleon’s army in the Moscow province”, from the “Brief Journal of Military Actions” about the struggle of the peasants of Belsky district. Smolensk province. with Napoleon's army, we see that the actions of peasant partisan detachments actually took place during the Patriotic War of 1812, mainly in the Smolensk province (10, pp. 118, 119, 123).

Memoirs, as well as memories, are not the most reliable source of information, since by definition, memoirs are notes from contemporaries telling about events in which their author directly took part. Memoirs are not identical to chronicles of events, since in memoirs the author tries to comprehend the historical context of his own life; accordingly, memoirs differ from chronicles of events in their subjectivity - in that the events described are refracted through the prism of the author’s consciousness with his own sympathies and vision of what is happening. Therefore, memoirs, unfortunately, provide practically no evidence in our case.

1) The attitude of the peasants in the Smolensk province and their willingness to fight is clearly traced in the memoirs of A.P. Buteneva (10, p. 28)

2) From the memoirs of I.V. Snegirev, we can conclude that the peasants are ready to defend Moscow (10, p. 75)

However, we see that memoirs and memoirs are not a reliable source of information, since they contain too many subjective assessments, and in the end we will not take them into account.

Notes And letters are also subject to subjectivity, but their difference from memoirs is such that they were written directly during these historical events, and not for the purpose of subsequent familiarization with them to the masses, as is the case with journalism, but as personal correspondence or notes, accordingly their reliability although it is questioned, they can be considered as evidence. In our case, notes and letters provide us with evidence not so much of the existence of the People’s War as such, but they prove the courage and strong spirit of the Russian people, showing that peasant partisan detachments were created in greater numbers based on patriotism, and not on the need for self-defense.

1) The first attempts at peasant resistance can be traced in a letter from Rostopchin to Balashov dated August 1, 1812 (10, p. 28)

2) From the notes of A.D. Bestuzhev-Ryumin dated August 31, 1812, from a letter to P.M. Longinova S.R. Vorontsov, from the diary of Ya.N. Pushchin about the battle of peasants with an enemy detachment near Borodino and about the mood of the officers after leaving Moscow, we see that the actions of peasant partisan detachments during the Patriotic War of 1812 were caused not only by the need for self-defense, but also by deep patriotic feelings and the desire to protect their homeland. enemy (10, pp. 74, 76, 114).

Journalism at the beginning of the 19th century it was subject to censorship in the Russian Empire. Thus, in the “First Censorship Decree” of Alexander I dated July 9, 1804, the following is stated: “... censorship is obliged to consider all books and works intended for distribution in society,” i.e. in fact, it was impossible to publish anything without permission from the regulatory authority, and accordingly, all descriptions of the exploits of the Russian people could turn out to be banal propaganda or a kind of “call to action” (12, p. 32). However, this does not mean that journalism does not provide us with any evidence of the existence of the People's War. Despite the apparent severity of censorship, it is worth noting that it did not cope with the assigned tasks in the best way. Professor of the University of Illinois Marianna Tax Choldin writes: “... a significant number of “harmful” works entered the country despite all the efforts of the government to prevent this” (12, p. 37). Accordingly, journalism does not claim to be 100% accurate, but it also provides us with some evidence about the existence of the People’s War and a description of the exploits of the Russian people.

Having analyzed the “Domestic Notes” about the activities of one of the organizers of peasant partisan detachments Emelyanov, correspondence to the newspaper “Severnaya Pochta” about the actions of peasants against the enemy and an article by N.P. Polikarpov “The Unknown and Elusive Russian Partisan Detachment”, we see that excerpts from these newspapers and magazines support evidence of the existence of peasant partisan detachments as such and confirms their patriotic motives (10, p. 31, 118; 1, p. 125) .

Based on this reasoning, we can come to the conclusion that the most useful in proving the existence of the People's War was reporting documentation due to the lack of subjectivity. Reporting documentation provides evidence of the existence of the People's War(description of the actions of peasant partisan detachments, their methods, numbers and motives), and notes And letters confirm that the formation of such detachments and the People's War itself was caused by Not only in order to self-defense, but also based on deep patriotism And courage Russian people. Journalism also reinforces both these judgments. Based on the above analysis of numerous documentation, we can conclude that contemporaries of the Patriotic War of 1812 realized that the People’s War took place and clearly distinguished peasant partisan detachments from army partisan detachments, and also realized that this phenomenon was not caused by self-defense. Thus, from all of the above, we can say that there was a People's War.

Chapter 2. General characteristics and comparative analysis of partisan detachments

The partisan movement in the Patriotic War of 1812 is an armed conflict between Napoleon's multinational army and Russian partisans on Russian territory in 1812 (1, p. 227).

Guerrilla warfare was one of the three main forms of war of the Russian people against Napoleon's invasion, along with passive resistance (for example, the destruction of food and fodder, setting fire to their own houses, going into the forests) and mass participation in militias.

The reasons for the emergence of the Partisan War were associated, first of all, with the unsuccessful start of the war and the retreat of the Russian army deep into its territory showed that the enemy could hardly be defeated by the forces of regular troops alone. This required the efforts of the entire people. In the overwhelming majority of areas occupied by the enemy, he perceived the “Great Army” not as his liberator from serfdom, but as an enslaver. Napoleon did not even think about any liberation of the peasants from serfdom or improvement of their powerless situation. If at the beginning promising phrases were uttered about the liberation of serfs from serfdom and there was even talk about the need to issue some kind of proclamation, then this was only a tactical move with the help of which Napoleon hoped to intimidate the landowners.

Napoleon understood that the liberation of Russian serfs would inevitably lead to revolutionary consequences, which is what he feared most. Yes, this did not meet his political goals when joining Russia. According to Napoleon’s comrades, it was “important for him to strengthen monarchism in France, and it was difficult for him to preach revolution to Russia” (3, p. 12).

The very first orders of the administration established by Napoleon in the occupied regions were directed against the serfs and in defense of the feudal landowners. The temporary Lithuanian “government”, subordinate to the Napoleonic governor, in one of the very first resolutions obliged all peasants and rural residents in general to unquestioningly obey the landowners, to continue to perform all work and duties, and those who would evade were to be severely punished, attracting for this purpose , if circumstances require it, military force (3, p. 15).

The peasants quickly realized that the invasion of the French conquerors put them in an even more difficult and humiliating position than they had been in before. The peasants also associated the fight against foreign enslavers with the hope of liberating them from serfdom.

In reality, things were somewhat different. Even before the start of the war, Lieutenant Colonel P.A. Chuykevich compiled a note on the conduct of active partisan warfare, and in 1811 the work of the Prussian Colonel Valentini, “The Small War,” was published in Russian. This was the beginning of the creation of partisan detachments in the War of 1812. However, in the Russian army they looked at the partisans with a significant degree of skepticism, seeing in the partisan movement “a disastrous system of fragmentation of the army” (2, p. 27).

The partisan forces consisted of detachments of the Russian army operating in the rear of Napoleon's troops; Russian soldiers who escaped from captivity; volunteers from the local population.

§2.1 Peasant partisan detachments

The first partisan detachments were created even before the Battle of Borodino. On July 23, after joining with Bagration near Smolensk, Barclay de Tolly formed a flying partisan detachment from the Kazan Dragoon, three Don Cossack and Stavropol Kalmyk regiments under the general command of F. Wintzingerode. Wintzingerode was supposed to act against the French left flank and provide communication with Wittgenstein's corps. The Wintzingerode flying squad also proved to be an important source of information. On the night of July 26-27, Barclay received news from Wintzingerode from Velizh about Napoleon’s plans to advance from Porechye to Smolensk in order to cut off the retreat routes of the Russian army. After the Battle of Borodino, the Wintzingerode detachment was reinforced with three Cossack regiments and two battalions of rangers and continued to operate against the enemy’s flanks, breaking into smaller detachments (5, p. 31).

With the invasion of Napoleonic hordes, local residents initially simply left the villages and went to forests and areas remote from military operations. Later, retreating through the Smolensk lands, the commander of the Russian 1st Western Army M.B. Barclay de Tolly called on his compatriots to take up arms against the invaders. His proclamation, which was apparently drawn up on the basis of the work of the Prussian Colonel Valentini, indicated how to act against the enemy and how to conduct guerrilla warfare.

It arose spontaneously and represented the actions of small scattered detachments of local residents and soldiers lagging behind their units against the predatory actions of the rear units of the Napoleonic army. Trying to protect their property and food supplies, the population was forced to resort to self-defense. According to the memoirs of D.V. Davydov, “in every village the gates were locked; with them stood old and young with pitchforks, stakes, axes, and some of them with firearms” (8, p. 74).

French foragers sent to villages for food faced more than just passive resistance. In the area of Vitebsk, Orsha, and Mogilev, detachments of peasants made frequent day and night raids on enemy convoys, destroyed their foragers, and captured French soldiers.

Later, the Smolensk province was also plundered. Some researchers believe that it was from this moment that the war became domestic for the Russian people. It was here that popular resistance acquired the widest scope. It began in Krasnensky, Porechsky districts, and then in Belsky, Sychevsky, Roslavl, Gzhatsky and Vyazemsky districts. At first, before the appeal of M.B. Barclay de Tolly, the peasants were afraid to arm themselves, fearing that they would later be brought to justice. However, this process subsequently intensified (3, p. 13).

In the city of Bely and Belsky district, peasant detachments attacked French parties making their way towards them, destroyed them or took them prisoner. The leaders of the Sychev detachments, police officer Boguslavsky and retired major Emelyanov, armed their villagers with guns taken from the French and established proper order and discipline. Sychevsky partisans attacked the enemy 15 times in two weeks (from August 18 to September 1). During this time, they destroyed 572 soldiers and captured 325 people (7, p. 209).

Residents of the Roslavl district created several horse and foot peasant detachments, arming the villagers with pikes, sabers and guns. They not only defended their district from the enemy, but also attacked the marauders making their way into the neighboring Elny district. Many peasant detachments operated in Yukhnovsky district. Having organized defense along the river. Ugra, they blocked the enemy’s path in Kaluga, provided significant assistance to the army partisan detachment D.V. Davydova.

Another detachment, created from peasants, was also active in the Gzhatsk district, headed by Ermolai Chetvertak (Chetvertakov), a private in the Kyiv Dragoon Regiment. Chetvertakov’s detachment began not only to protect villages from marauders, but to attack the enemy, inflicting significant losses on him. As a result, throughout the entire space of 35 versts from the Gzhatsk pier, the lands were not devastated, despite the fact that all the surrounding villages lay in ruins. For this feat, the residents of those places “with sensitive gratitude” called Chetvertakov “the savior of that side” (5, p. 39).

Private Eremenko did the same. With the help of the landowner. In Michulovo, by the name of Krechetov, he also organized a peasant detachment, with which on October 30 he exterminated 47 people from the enemy.

The actions of peasant detachments became especially intensified during the stay of the Russian army in Tarutino. At this time, they widely deployed the front of the struggle in the Smolensk, Moscow, Ryazan and Kaluga provinces.

In Zvenigorod district, peasant detachments destroyed and captured more than 2 thousand French soldiers. Here the detachments became famous, the leaders of which were the volost mayor Ivan Andreev and the centenarian Pavel Ivanov. In Volokolamsk district, such detachments were led by retired non-commissioned officer Novikov and private Nemchinov, volost mayor Mikhail Fedorov, peasants Akim Fedorov, Philip Mikhailov, Kuzma Kuzmin and Gerasim Semenov. In the Bronnitsky district of the Moscow province, peasant detachments united up to 2 thousand people. History has preserved for us the names of the most distinguished peasants from the Bronnitsy district: Mikhail Andreev, Vasily Kirillov, Sidor Timofeev, Yakov Kondratyev, Vladimir Afanasyev (5, p. 46).

The largest peasant detachment in the Moscow region was a detachment of Bogorodsk partisans. In one of the first publications in 1813 about the formation of this detachment, it was written that “the head of the economic volosts of Vokhnovskaya Yegor Stulov, the centurion Ivan Chushkin and the peasant Gerasim Kurin, the Amerevskaya head Emelyan Vasilyev gathered the peasants under their jurisdiction, and also invited neighboring ones” (1, p. 228).

The detachment consisted of about 6 thousand people in its ranks, the leader of this detachment was the peasant Gerasim Kurin. His detachment and other smaller detachments not only reliably defended the entire Bogorodskaya district from the penetration of French marauders, but also entered into armed struggle with enemy troops.

It should be noted that even women took part in forays against the enemy. Subsequently, these episodes became overgrown with legends and in some cases did not even remotely resemble real events. A typical example is with Vasilisa Kozhina, to whom popular rumor and propaganda of that time attributed neither more nor less than the leadership of a peasant detachment, which in reality was not the case.

During the war, many active participants in peasant groups were awarded. Emperor Alexander I ordered to reward the people subordinate to Count F.V. Rostopchin: 23 people “in command” received insignia of the Military Order (St. George’s Crosses), and the other 27 people received a special silver medal “For Love of the Fatherland” on the Vladimir Ribbon.

Thus, as a result of the actions of military and peasant detachments, as well as militia warriors, the enemy was deprived of the opportunity to expand the zone under his control and create additional bases to supply the main forces. He failed to gain a foothold either in Bogorodsk, or in Dmitrov, or in Voskresensk. His attempt to obtain additional communications that would have connected the main forces with the corps of Schwarzenberg and Rainier was thwarted. The enemy also failed to capture Bryansk and reach Kyiv.

§2.2 Army partisan units

Along with the formation of large peasant partisan detachments and their activities, army partisan detachments played a major role in the war.

The first army partisan detachment was created on the initiative of M. B. Barclay de Tolly. Its commander was General F.F. Wintzengerode, who led the united Kazan Dragoons, 11 Stavropol, Kalmyk and three Cossack regiments, which began to operate in the area of Dukhovshchina.

The detachment of Denis Davydov was a real threat for the French. This detachment arose on the initiative of Davydov himself, lieutenant colonel, commander of the Akhtyrsky Hussar Regiment. Together with his hussars, he retreated as part of Bagration’s army to Borodin. A passionate desire to bring even greater benefit in the fight against the invaders prompted D. Davydov to “ask for a separate detachment.” Lieutenant M.F. strengthened him in this intention. Orlov, who was sent to Smolensk to find out the fate of the seriously wounded General P.A., who was captured. Tuchkova. After returning from Smolensk, Orlov spoke about the unrest and poor rear protection in the French army (8, p. 83).

While driving through the territory occupied by Napoleonic troops, he realized how vulnerable the French food warehouses, guarded by small detachments, were. At the same time, he saw how difficult it was for flying peasant detachments to fight without a coordinated plan of action. According to Orlov, small army detachments sent behind enemy lines could inflict great damage on him and help the actions of the partisans.

D. Davydov made a request to General P.I. Bagration to allow him to organize a partisan detachment to operate behind enemy lines. For a “test,” Kutuzov allowed Davydov to take 50 hussars and 1,280 Cossacks and go to Medynen and Yukhnov. Having received a detachment at his disposal, Davydov began bold raids behind enemy lines. In the very first skirmishes near Tsarev - Zaimishch, Slavkoy, he achieved success: he defeated several French detachments and captured a convoy with ammunition.

In the fall of 1812, partisan detachments surrounded the French army in a continuous mobile ring.

A detachment of Lieutenant Colonel Davydov, reinforced by two Cossack regiments, operated between Smolensk and Gzhatsk. A detachment of General I.S. operated from Gzhatsk to Mozhaisk. Dorokhova. Captain A.S. Figner and his flying detachment attacked the French on the road from Mozhaisk to Moscow.

In the area of Mozhaisk and to the south, a detachment of Colonel I.M. Vadbolsky operated as part of the Mariupol Hussar Regiment and 500 Cossacks. Between Borovsk and Moscow, the roads were controlled by a detachment of captain A.N. Seslavina. Colonel N.D. was sent to the Serpukhov road with two Cossack regiments. Kudashiv. On the Ryazan road there was a detachment of Colonel I.E. Efremova. From the north, Moscow was blocked by a large detachment of F.F. Wintzengerode, who, by detaching small detachments from himself to Volokolamsk, on the Yaroslavl and Dmitrov roads, blocked access for Napoleon’s troops to the northern regions of the Moscow region (6, p. 210).

The main task of the partisan detachments was formulated by Kutuzov: “Since now the autumn time is coming, through which the movement of a large army becomes completely difficult, then I decided, avoiding a general battle, to wage a small war, because the divided forces of the enemy and his oversight give me more ways to exterminate him , and for this, being now 50 versts from Moscow with the main forces, I am giving up important units in the direction of Mozhaisk, Vyazma and Smolensk” (2, p. 74). Army partisan detachments were created mainly from Cossack troops and were unequal in size: from 50 to 500 people. They were tasked with bold and sudden actions behind enemy lines to destroy his manpower, strike at garrisons and suitable reserves, disable transport, deprive the enemy of the opportunity to obtain food and fodder, monitor the movement of troops and report this to the General Headquarters of the Russian Army . The commanders of the partisan detachments were indicated the main direction of action and were informed of the areas of operation of neighboring detachments in the event of joint operations.

The partisan detachments operated in difficult conditions. At first there were many difficulties. Even residents of villages and villages at first treated the partisans with great distrust, often mistaking them for enemy soldiers. Often the hussars had to dress in peasant caftans and grow beards.

The partisan detachments did not stand in one place, they were constantly on the move, and no one except the commander knew in advance when and where the detachment would go. The partisans' actions were sudden and swift. To swoop down out of the blue and quickly hide became the main rule of the partisans.

The detachments attacked individual teams, foragers, transports, took away weapons and distributed them to the peasants, and took dozens and hundreds of prisoners.

Davydov’s detachment on the evening of September 3, 1812 went to Tsarev-Zamishch. Not reaching 6 versts to the village, Davydov sent reconnaissance there, which established that there was a large French convoy with shells, guarded by 250 horsemen. The detachment at the edge of the forest was discovered by French foragers, who rushed to Tsarevo-Zamishche to warn their own. But Davydov did not let them do this. The detachment rushed in pursuit of the foragers and almost burst into the village together with them. The convoy and its guards were taken by surprise, and an attempt by a small group of French to resist was quickly suppressed. 130 soldiers, 2 officers, 10 carts with food and fodder ended up in the hands of the partisans (1, p. 247).

Sometimes, knowing the location of the enemy in advance, the partisans launched a surprise raid. Thus, General Wintzengerode, having established that in the village of Sokolov - 15 there was an outpost of two cavalry squadrons and three infantry companies, allocated 100 Cossacks from his detachment, who quickly burst into the village, destroyed more than 120 people and captured 3 officers, 15 non-commissioned officers -officers, 83 soldiers (1, p. 249).

Colonel Kudashiv's detachment, having established that there were about 2,500 French soldiers and officers in the village of Nikolskoye, suddenly attacked the enemy, destroyed more than 100 people and captured 200.

Most often, partisan detachments ambushed and attacked enemy transport on the way, captured couriers, and freed Russian prisoners. The partisans of General Dorokhov's detachment, operating along the Mozhaisk road, on September 12 captured two couriers with dispatches, burned 20 boxes of shells and captured 200 people (including 5 officers). On September 6, Colonel Efremov’s detachment, having met an enemy column heading towards Podolsk, attacked it and captured more than 500 people (5, p. 56).

Captain Figner's detachment, which was always close to the enemy troops, in a short time destroyed almost all the food in the vicinity of Moscow, blew up an artillery park on the Mozhaisk road, destroyed 6 guns, killed up to 400 people, captured a colonel, 4 officers and 58 soldiers (7 , p. 215).

Later, the partisan detachments were consolidated into three large parties. One of them, under the command of Major General Dorokhov, consisting of five infantry battalions, four cavalry squadrons, two Cossack regiments with eight guns, took the city of Vereya on September 28, 1812, destroying part of the French garrison.

§2.3 Comparative analysis of peasant and army partisan detachments of 1812