What is harmony? Musical harmony - colors of music "The idea of musical harmony".

Read also

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

Chapter 1. The social purpose and content of musical art, which corresponded to classical harmony (in comparison with the previous period in the history of European art). Formation of new genres and their genesis. The development of instrumental music, as an indicator of the formation of an independent musical art - the importance of harmony in the autonomous art of music. The connection of harmony with rhythm (meter), texture and form in modern European art. The ratio of expressive and organizational principles in classical harmony

1) The social purpose and content of musical art, which corresponded to classical harmony (in comparison with the previous period in the history of European art)

As you know, the development of all types of art is ultimately determined by a single socio-historical process. But at the same time, this very process can lead to a very unequal character and unequal destinies of various arts in certain periods. Therefore, it is far from always possible to draw any convincing parallel between phenomena related to different areas of artistic creation. It is difficult, for example, to find an analogy for Bach's work in other arts of the same era. At the same time, aesthetically related phenomena in different types of art often turn out to be not synchronous.

First of all, it is necessary to recall the new attitude that took shape during the Renaissance. The human personality, its right to the fullness of feelings and their expression, the right to joy and happiness (moreover, earthly, and not heavenly) - that's what stood at the center of this attitude and the art associated with it. It was art not only about an earthly man, but also for him: hence the appeal to the natural sensory perception of the world by man and a strong reliance on the laws of such perception. Although the Renaissance, which marked a turning point in the history of all Western European culture, ultimately led to a corresponding leap in the field of musical art, this leap did not occur during the Renaissance itself, but later - in the 17th century.

The ideas, which were stimulated by the Renaissance, could begin their true development in music only when a new form of professional music-making, independent of the church, arose, i.e. when a new powerful organizational center for professional musical art was formed. It turned out to be an opera that took shape in the 17th century.

2) Formation of new genres and their genesis

Only under the conditions of a new genre could the new content of musical art find its true expression. And the new content and the new genre also led to the dominance of a new technical structure of music, new principles of musical language and form. The strict choral polyphony of church music, in which any individually bright melodies did not stand out, was replaced by an emotionally expressive melody that concentrates the main features of the image and subordinates the harmonic accompaniment. This gamophonic-harmonic warehouse somehow relied on samples of everyday and folk music (especially melodic in Italy, where the opera was born), but it received its final recognition, full development and professional development only in the aria, which became the main element of the opera and the main the exponent in it of the character, feelings and aspirations of the human person.

If the abstract-contemplative art of a strict style presupposed not only the smoothness of lines, consonance of consonance, but also a more or less the same level of general tension, a relatively flat emotional and dynamic curve, then music that embodied the various mental movements of a human personality was naturally associated with pronounced changes in tension and tranquility. Therefore, the authoritative ratio of the dominant instability and the tonic stability that resolves it, which was used in the stack style mainly for the syntactic completion of musical thought, gradually turned (together with the inverse - semi-authentic - C - M ratio) into the main harmonic means that dominates throughout the entire musical thought and acquires not only constructive and syntactic, but also expressive and dynamic meaning.

3) The development of instrumental music as an indicator of the formation of an independent musical art - the importance of harmony in the autonomous art of music

Along with the opera, purely instrumental creativity developed, new instrumental forms arose. Largely associated with the influence of opera, partly formed within it (as instrumental episodes) or experienced its strong influence (solo instrumental concert), but partly developed independently of the opera (trio sonata) and even ahead of its emergence (organ music of the late 16th century ).

Instrumental creativity, naturally, did not break with the general intonation, i.e. vocal-speech, expressive-vocal, the basis of music, nor with many more specific figurative-genre spheres that have developed in vocal art. Throughout its history, non-programmed instrumental music somehow absorbed the types of musical imagery, musical thematicism that was previously created in vocal, stage, ritual music, i.e. software in a broad sense. At the same time, instrumental creativity greatly expanded the possibilities of music in many directions and had a huge impact on other areas. In it, musical images were formed, characterized by a particularly high concentration and generalization, and in addition - and this is even more important - methods were created for a wide and multifaceted development of musical ideas, - development, which differed in large, complex and perfect musical forms, which were later also used in opera. Of course, the logic of thematic development — motivational and thematic juxtapositions and transformations — was also of great importance for large instrumental forms of music. But this logic will develop only after the crystallization of the homophonic warehouse.

4) The relationship of harmony with rhythm (meter), texture and form in modern European art

The homophonic warehouse also transformed the metro-rhythmic organization of music. A strict accent metric emerged. Heavy beats of measures began to be accentuated by bass and regular changes in harmony. With more rare changes in harmony, metric ratios began to spread to entire groups of measures: one of two, three, and even four measures of a musical phrase began to stand out as a strong one. And the location of harmonic cadances at similar points of similar structures allowed the metric organization to cover an even greater extent.

In the area of the musical fabric itself, the homophonic warehouse created that special relief (different plans), which the old polyphony, based on the relative equality of voices, did not know. In addition to dividing into a melody, which is, as it were, in the foreground, and accompaniment, the accompaniment itself, in turn, differentiates into supporting basses and middle voices that maintain (or repeat) harmony. In character and meaning, it is somewhat analogous to the consistent use of perspective in painting.

Everything described so far is a single complex of phenomena that characterizes the general appearance of post-renaissance music. It also included polyphony, but in a different form and in a different role in comparison with the strict style. This complex also characterizes the scale of the revolution that took place in the art of music after the Renaissance.

In the next large complex of phenomena, it is possible to single out - generally and schematically - two main points that determined the main ones and determined the formation of the classical system of musical thinking in the 17th - 18th centuries. These moments are the embodiment of new expressiveness (new content) and the assertion of the independence of musical art, which required its special internal organization.

The fact that this process had two closely intertwined sides is confirmed by many phenomena. The very fact of the simultaneous development of opera and instrumental creativity partly belongs to them. But this latter signified a certain emancipation of music from the vocal-speech principle, and a huge development of its own properties in a new sphere. This development was most clearly manifested in solo instrumental concert, especially in violin, which, like the opera aria, combined a new individualized melody with virtuoso elements.

In the same era, an equally intense search was conducted in the field of temperament - a search brought about by the demands of the musical system, logic, i.e. requirements, outside of which it was impossible to develop independent and developed musical forms.

5) The ratio of expressive and organizational principles in classical harmony

However, it was not always easy to combine the solution of the two main historical problems facing the music of the 17th and early 18th centuries. In order to defend the independence of the musical art, which was for the first time asserted, a very strong and clear internal organization, internal logic, moreover simple and generalized at its core, was needed. And she could not but impose serious restrictions on the free outpourings of expressiveness, on the use of especially vivid means, even if they embody a particular emotional state or successfully depict a stage situation, but do not obey the strict discipline of form. In the end, among the enormous diversity of various directions and creative attempts of that time, history has chosen and drew some optimal line of development, discarding much that may be interesting in itself, but did not contribute at this stage to solving the described two-sided complex of problems.

The homophonic melody as a whole has developed as individually expressive, melodious, extended and at the same time very strictly organized, clearly divided into large and small parts, subordinate to simple harmonic logic and dance rhythmic grouping, clearly expressed in typical vocal samples, where it is true , sometimes somewhat veiled.

But even if melody was forced to subordinate to a large extent the particular expressive effects of a more generalized organization, then this was much more related to the harmony accompanying the melody, for its organizing role, as is clear from all the preceding, was especially great. This role required strict discipline. Harmony had to restrain and limit its natural striving for various particular, characteristic, purely specific effects. A diminished seventh chord, as an expression of horror or catastrophe, confusion or anxiety, pathetically sounding chords with an increased sixth, a Neapolitan sixth chord that deepens and elevates the minor expressiveness - this is almost the entire assortment of sharp-character chords of that time, selected in the process of forming the classical system of harmonic thinking. Basically, the content side of harmony consisted in enhancing the expressiveness of the melody itself, in explaining the modal-functional meaning of its turns, identifying and emphasizing the general major or minor color of music, in juxtapositions and mutual transitions of these modal-expressive qualities, in creating a general emotional tonic effect by alternating harmonic stability and instability ... Harmony contributes to the embodiment of the dynamic side of emotions - the rise and fall of their tension - through the appropriate use of the same properties of stability and instability. The nature and tasks of the new musical art left it to the share of classical harmony to participate in the transmission of mainly those aspects of emotional and psychological states, the embodiment of which by harmony at the same time best serves as the organization of the whole, its dynamics, logic, and form.

The ratio of melody and harmony that developed in the homophonic warehouse, which was then developed and overcome, is typical for it. It arose with such an organic necessity that it can seem eternal, and yet it was brought into being by a completely unique combination of historical circumstances and conditions. The paradox also lies in the fact that for a perfect musical ear, a homophonic melody with a simple harmonic accompaniment often seems too soft, smooth, unobstructed, while in reality the properties of the homophonic-harmonic structure considered here were the result of the action of just a particularly strict discipline necessary for the music of that time. so that it can withstand and assert itself in the struggle both for the embodiment of the new content and for the existence as an independent art.

At the beginning of the 17th century, some supporters of the homophonic warehouse declared polyphony to be "barbaric" and finally a thing of the past. They were, of course, mistaken both in their assessment of the phenomenon and in their predictions: we admire the creations of the old masters and we know that with them only the era of strict polyphony ended, and not polyphony in general. But the pattern of such mistakes is also clear to us: the new, young type of art, which asserts itself as opposed to the old and mature, is often inclined to underestimate and even deny its significance. And at the same time, this new type reaches its own maturity only when it manages to restore the temporarily interrupted connection with tradition and include the essential elements of the old art.

The new type of music that emerged in the 17th century, connected with new content, new genres and forms, and with a new technical warehouse, could not immediately reach great heights, no matter how gifted its individual representatives were. Full historical maturity was brought to the new type of music not by the 17th century, in any case, not by its first half - the time of fermentation, searches, formation - but the next period. And, perhaps, the absolutely exceptional flourishing of musical creativity in the 18th century, which gave the world such geniuses as Bach, Handel, Gluck, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, was due to a special historical concentration of tasks and accomplishments of two different eras, as if by the merger of that “ Renaissance ", which has long been felt in music, but for a long time did not find classical expression in it, with the ideas and aspirations of the Age of Enlightenment.

Chapter 2. Correlation in the era of classicism of melody and harmonious accompaniment in the plans: emotional and rational, individualized and general, in the organization of the modal (tonal) structure; take also the material from pp. 564-566. Classical harmony as a grammatical category. Possibilities of melody and harmony in shaping at various levels

1) The ratio in the era of classicism of melody and harmonious accompaniment in the plans: emotional and rational, individualized and general, in the organization of the modal (tonal) structure; take also the material from pp. 564-566

music art harmony rhythm

The specific side of the melody, which distinguishes it from other elements of music, for example from harmony, is the line of altitude changes in one voice, while the specific side of the melody that distinguishes it from life prototypes is not the line of altitude changes in itself, but a special organization - modal system of height ratios and connections.

In response to EF Napravnik's request to facilitate the role of Joanna in the opera "The Maid of Orleans", freeing her from notes that are too high for a certain performer, Tchaikovsky resolutely refused to transfer the corresponding passages to a different key. He wrote: "As for the E-major" episode in the duet of the last act, after long agonizing hesitation I preferred to disfigure the melody rather than change the modulation. about other changes and inviting Napravnik to introduce them here and there at his discretion, Tchaikovsky again points out: "Let the melodic pattern be disfigured better than the very essence of musical thought, which is directly dependent on modulation and harmony, with which I have become accustomed ...".

A change in one or two sounds of a melody, although it affects the immediate expressiveness of a given moment, can be limited to this action, i.e. have a local meaning, while the replacement of any harmony, modulation and tonality inevitably affects the general logic of any construction.

Let us now turn to the concept of Ernst Kurt, one of the outstanding theoretical musicologists of the 20th century. In his Fundamentals of Linear Counterpoint, he persistently pursues the idea that the essence of melody and the main regularities of the melodic line find their most vivid expression not in the style of the Viennese classics and, in general, in the music based on the homophonic-harmonic structure. The homophonic type of melody is too much subordinated - in Kurt's opinion - to the metric severity of uniform accents, rhythmic grouping, as well as the logic of harmonic cadences and regular changes in harmony, so that free, unrestrained melodic breathing can fully manifest itself in it - the development of the melodic line itself in accordance with by its own laws. On the contrary, in Bach's style, especially in his instrumental compositions, such a development is expressed incomparably more vividly, the melodic line is freer and more independent; therefore, one should study the patterns of melody on the basis of this particular style.

Kurt's views turned out to be related to the point of view of many theorists, who are quite far from Kurt in their musical and creative sympathies. In particular, the propagandists of atonal music emphasize even more sharply than Kurt that among the Viennese classics and romantics the melody is dependent and is only a horizontal interpretation of the harmonic sequence. Finally, Rudolf Reti, who, on the contrary, considers atonalism and dodecaphony to be one-sided phenomena, created the concept of melodic and harmonic tonality, according to which it is the harmonic tonality that dominates in classical music, which again means the subordinate position of melody in relation to harmony.

Obviously, these views contain a significant amount of truth, however, at first glance, they contradict the basic ideas about the homophonic-harmonic warehouse. After all, it presupposes the main melodic voice and harmonic accompaniment subordinate to it.

True, the words "harmonic accompaniment" and "harmony" are not equivalent: not only the accompaniment, but also the main melodic voice participates in the formation of harmony. However, the accompaniment usually and without the main voice embodies harmony quite fully. A melody without accompaniment only in one way or another hints at harmony, implies it, and at the same time it is far from always unambiguous and definite.

When they talk about the subordinate position of classical and romantic melody in relation to harmony, they mean not the strength of the emotional expressiveness of the melody and not the individual brightness of the image it represents. We are talking about the lesser forming energy of melody, the melodic line, about its less constructive "load" in comparison with the formative role of harmony among the Viennese classics, on the one hand, and with the role of the melodic line in Bach, in old tunes and in some phenomena of modern music - with another. It would be possible, bearing in mind the relatively insignificant participation of the homophonic melodic line in the organization of the form of the whole, to say: yes, the homophonic melody is, of course, the queen; but this is an English queen; she reigns but does not rule. And perhaps this kind of comparison is capable of grasping one of the most important aspects of the relationship between melody and harmony in a homophonic warehouse.

The logic of the melodic line is very individual - incomparably more individual than the logic of harmonic functions.

The comparison can be continued. A person who is not in opposition to society can perceive its laws and customs as their own and follow them naturally, without coercion. Of course, these laws and customs in some way limit the personality, but in many other things, on the contrary, they liberate, liberate it. So, in a society rich in traditions and rules, for a member of society there is no need to decide anew every time how to act in a particular typical case, and therefore the intellectual energy of a person and his individuality can more fully manifest themselves in more interesting and higher spheres of life and activities.

In a similar way, the classical homophonic melody, striving first of all for individual expressiveness, willingly entrusts some general “control functions” to harmony, freeing itself to solve its own problems, and in some other respects submitting to harmony very organically - not as an external principle, but as its own harmony , outside of which the homophonic melody does not seem to think of itself.

The role of harmony for a melody in homophonic music is that harmony not only supports, strengthens the melody and clarifies the modal meaning of its turns and not only subordinates it to itself in a constructive sense, but in many aspects liberates it, frees it, relieves it of some responsibilities , allows her to soar and reign freely, to set and solve such problems that would be unthinkable without harmony. As a result, listening to homophonic music, we nevertheless find ourselves first of all in the realm of melody, albeit supported and largely governed by harmony.

2) Classical harmony as a grammatical category

The described relative autonomy of classical harmony is closely related to some of its other properties. As you know, the categories, the expression of which in a given language is obligatory under certain conditions, belong to grammatical categories. Remembering that some third-order harmony must necessarily be expressed at every moment of a classical work and, in addition, knowing about the capital significance of harmonic sequence for the logic of the work, we can talk about many categories of classical harmony as grammatical obligatory categories of the corresponding musical styles

And finally, all that has been said makes it obvious the connection between the relative autonomy of classical harmony and its not very high degree of individualization. This directly follows from the fact that more or less similar chord sequences perform the function of grammatical control in topics of a different nature. Naturally, in such sequences, typical traits prevail over individual ones. Already in the first and second chapters it was explained that the homophonic-harmonic system liberated the individual expressiveness of the melody at the cost of limiting the expressiveness of harmony to several specific areas. The grammatical properties of harmony allow us to look at this issue from a somewhat new angle.

The high degree of relative autonomy of the laws of classical harmony, the grammatical meaning of many of these laws and the relatively low individualization of most functional-harmonic sequences are, in essence, different sides of one phenomenon. And a radical change in the role of harmony in the work of many composers of the 20th century who do not abandon tonality, a change in the place of harmony among other elements of music, and, finally, a new character of the chords themselves and their sequences are primarily due to the fact that harmony is losing the meaning of the generally obligatory grammatical basis of the musical language. its laws are deprived of the previous degree of autonomy, but it becomes incomparably more individualized, individually expressive.

The controlling and reconciling role of harmony is so great that if, to a certain extent, it is legitimate to compare music with verbal language, then it is natural to liken harmony in a homophonic warehouse to the basis of language grammar.

The chords of the classical system of harmony, being elements of a not very rich harmonic "vocabulary", are at the same time, as it were, grammatical categories of homophonic music. The action of these grammatical categories extends to the melody, each sound of which is easily defined in terms of its relation to harmony. And this remains in force even when several melodically individualized voices sound simultaneously on a harmonious basis and one or another type of polyphony arises.

In strictly style music, polyphony was an obligatory grammatical category. Vertical compositions, which arose as a result of voice leading and had to satisfy the conditions of consonance, could acquire one or another expressive or coloristic meaning, but did not carry the function of controlling the form and therefore their distribution according to any strict functional headings did not matter.

3) Possibilities of melody and harmony in shaping at various levels

Not only the support and strengthening of the melody, its liberation in all possible aspects, not only the elementary control of the melody form (first of all, its division into cadences), but also the very interest, novelty, freshness, originality of individual melodic turns are to a very large extent determined in homophonic music by harmony, those. the relationship between these turns and their tonal-harmonic basis.

The very fact of symmetrical harmonization of melodic sequences among the Viennese classics was noted in musicological literature, but its meaning, perhaps, has not yet been fully disclosed. A sequence is not a closed structure, it easily admits continuation by inertia and even attracts to it: if there were two links, then in principle the third and fourth can follow. The harmonic turnover of TDDT, on the other hand, is closed. And constructions similar to those given in example 9 (p. 97 Beethoven Trio op.1 no. 2) once again demonstrate the primacy of the formative role of harmony over the role of the melodic line: in the Beethoven trio we do not wait after two links for the beginning of the third, but perceive the construction, thanks to harmony as relatively closed. The number of such examples in the music of the Viennese classics is very large.

In the post-Beethoven period, a tendency towards an increase in the formative role of the melodic principle is again making its way - in various aspects. The melodic connections in harmony itself are strengthened.

In the system of homophonic-harmonic music, the functions of melody and harmony are very clearly differentiated. Above we have already described those tasks of art that made just such a differentiation vital at a certain stage of development. But once the system was established, it became possible and desirable to soften the differentiation of some sort. Indeed, the voices that make up a typical homophonic accompaniment are devoid of independent melodic interest, and their entire totality participates very little in the formation of uniquely individual features of an artistic image (the same elementary harmonic sequence can be found in a wide variety of themes). Such a situation could satisfy the conditions and requirements of simple song and dance genres, small plays, and for a long time also opera arias. But when striving for richer, more complex, developed musical expressiveness, it is easily discovered that a purely homophonic accompaniment is, as it were, an underloaded element of the system, which can be assigned, without prejudice to its basic functions, some additional responsibilities. And the accompanying voices are saturated with expressive melodic figuration, and sometimes acquire a certain independence, which ultimately leads to polyphony on a harmonious basis. Thus, the differentiation of the functions of the main and accompanying voices becomes less sharp. However, this natural internal tendency in the development of the system is realized only because it is in accordance with the tasks of the art of that time: it contributes to the deepening and enrichment of musical expressiveness, the development of musical forms; it naturally renews the connection with the polyphonic tradition, temporarily interrupted by a purely homophonic structure, and at the same time does not violate the new functional-harmonic logic. It is indicative that the seemingly equally natural tendency to saturate the accompaniment with colorful harmonious expression has not yet been fully realized in the music of the 18th century: the corresponding tasks faced the art of music only in the next century.

Chapter 3. Opposition of emotional content in the contrast of major and minor and their relationship in classical music. Possibilities of enlarging functional relations in harmony (on the example of comparative analysis of typical turnovers of TD-TD, TD-DT). Dialectics of tonal-thematic relationships in sonata form. The question of the procedural and dynamic side of the content of classical musical art and its embodiment through harmony

1) Opposition of emotional content in the contrast of major and minor and their relationship in classical music

Now it is already possible to elucidate in more detail the question of how harmony participates in solving the problems of that new musical art, which ultimately arose under the influence of the ideas and worldviews of the Renaissance, but only in the Age of Enlightenment could it acquire its highest classical forms. Let us dwell first of all on the role of harmony in a new, more open and complete expression of the emotional world of a person.

Emotions, as you know, have two sides: qualitative certainty and the degree of tension, the changes of which form a certain dynamic process.

Of all the variety of emotions, classical music has focused its attention mainly on the expression (and opposition) of joy and sadness in their various shades and gradations - from exultation and delight to sorrow and despair. Naturally, music, directly addressed to a person and his feelings, sought, in contrast to the sublimely aloof cult art, to convey the character of emotions with great relief and clarity. It is no less natural that she not only used numerous private means for this, but, having become a completely independent art, inevitably had to include the ability to express opposite emotions at the very basis of her internal organization, i.e. how to program this ability in your specific system. Hence - the double-frettedness of classical harmony, which reduces the numerous modes to two main ones - major and minor. At the same time, as already mentioned, the expressiveness of harmony in homophonic music has developed as a rather generalized one: harmony seeks to embody not so much the entire wealth of shades of various emotions as their basic character. Two opposite modes, based on the existence of two different types of consonant triad, are therefore necessary and sufficient for solving its problems.

Linking both with the opposite of the modal color, similar to the ratio of light and shadow, and with the expression of the joy of sadness, the contrast of major and minor acquires the ability to play an important role in the generalized embodiment of the most diverse contrasts of reality (good and evil, life and death, etc.) , as well as in the embodiment of man's striving for happiness, overcoming darkness. And, finally, the contrast of frets, like other contrasts, can also serve as one of the means of shaping that is widely used in classical music.

The opposition of major and minor does not mean, of course, that every piece written in the major scale is joyful, cheerful, cheerful, and in the minor scale it is sad, sad.

It should also be borne in mind that the qualities of major and minor themselves can be expressed to varying degrees and are capable of entering into various combinations with each other: for example, in a harmonic major there is an element of a minor. Combinations of this kind are capable of producing a very different expressive effect, depending on all other conditions. For example, sometimes a harmonic major, introducing an element of the opposite mode, only sharpens - due to the emerging contrast - the basic major character of the music, which takes on a more intense, exalted or ecstatic tone. In other cases, the major with abundant elements of the minor of the same name, in particular with the wide development of the harmonic sphere of low degrees, sounds like a kind of "poisonous major" or "major with the opposite sign" and can make an even stronger impression than the minor. Note, however, that the Viennese classics mainly use the basic, primary possibilities of major and minor and do this more often catchy and generalized than detailed, because the Viennese-classical harmony itself is the carrier of mainly generalized musical expressiveness and musical logic.

It goes without saying, too, that major and minor, in all their described functions, operate within the framework of a system fixed by tradition, where they are compared, contrasted and serve to distinguish between the corresponding shades of expressiveness. The classical system used for its own purposes the fact of the existence of only two types of consonant triad, sharpening their difference to the expressiveness of semantic contrast.

On the one hand, the two basic modes act as equal in their opposite expressiveness, and this reflects a certain balance of opposite principles in various contrasts of reality. On the other hand, this equality is far from complete. For the life-affirming aesthetics of the Renaissance, and then of the musical classics of the 18th century, considers darkness, shadow only as shading of light and evaluates grief and evil, as it were, from the standpoint of joy and goodness, i.e. as a kind of distortion of the natural order of things.

The very names of the two modes also do not indicate their complete equality. The French names majeur and mineur mean greater (superior) and lesser (inferior). And if these names are associated with the major and minor third, then the Italian designations dur and moll - hard and soft - acquire the meaning of expressiveness characteristics. PI Tchaikovsky gives in his Guide to Harmony the following characterization of major and minor triads: “The minor third of a minor triad imparts to this chord a character of relative weakness, softness, so that triads of this kind, in terms of the meaning they have in harmony, cannot become along with major triads; they exist as if to serve as an excellent contrast to the strength and power of the latter. "

Obviously, one cannot assert the complete equality of hard and soft, strong and weak; the above quote directly speaks of the inequality of major and minor triads.

The minor, however, also has specific advantages over the major in the sense of dynamic potencies: the strong, the highest does not strive to become weak, the lowest; the weak and the lowest would usually like to become the strong and the highest. But the point is not in the names, but in the fact that the opposite emotions, with the embodiment of which are primarily associated with major and minor, also have a clearly expressed dynamic asymmetry. The state of grief does not satisfy the person, he wants it to pass, to be replaced by another state. But he does not at all seek to exchange joy for sorrow. Ultimately connected with this is the dominance of the major over the minor in the music of the classics, and the somewhat lower stability of the minor in comparison with the major, as well as some tendency of the minor to the major, but not vice versa. Needless to say, this all has its equivalent in the material structure of major and minor.

The described unequal relationship is manifested in a number of related facts. For example, a huge number of minor works of classics ends in major (in particular, many minor cyclic works have major final), while there are very few reverse examples.

In general, major pieces often dispense with a contrasting minor theme or part, while minor pieces in most cases contain some kind of contrasting major episode. Finally, we add that a number of classical composers - Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Glinka - the very number of major works far exceeds the number of minor ones. And this, of course, is related to the foundations of the aesthetics of musical classicism.

Of all the elements of music, harmony alone developed already in the 18th century a huge variety of qualitatively different means, embodying greater or lesser stability and instability, tension and relaxation, movement and relative peace, imbalance and its restoration, possible gravitation and support. A variety of scales and forms of manifestation of this kind of relationship is one of the essential properties of classical harmony.

Of course, this or that selection of some main, reference points and the grouping around them of other - unstable or less stable - moments are inherent in musical art and serve as a necessary prerequisite for musical form. They disappear only under certain specific conditions, which represent special, as it were, extreme cases. But that definiteness of the opposition of stability and instability, that force of gravitation of instabilities to foundations, that rich differentiation of numerous phenomena related to this and a complex multi-component system of their connections, subordination and subordination, which has developed in classical harmony, is characteristic only of it alone.

Already within the limits of the tonic chord there is a more stable form - a triad in the basic form - and a less stable one - a sixth chord. But the triad in its basic form can also be given in different melodic positions, one of which (the position of the prima) is the most stable. A fundamental difference between consonance and dissonance is added to the unequal degrees of tension of the basic type of any chord and its various inversions, and the consonance that resolves the dissonance is perceived as a moment of relative tranquility also in the case when the consonant chord is unstable in a given key, i.e. non-tonic. Moreover, even a dissonant chord can serve as a solution to some of the greater tension determined by non-chord sounds, primarily retentions, and thus, in addition to opposing consonance and dissonance. For classical harmony, it is also essential to contrast the actual chords as forms of more stable and so-called random harmonic combinations, gravitating and resolving into the correct chords. Finally, the chromatic elements introduced into the chords and their sequences also create additional tension in comparison with the diatonic basis of the scale.

From this it is clear that distinguishing the influence of the modal color (major and minor) and the harmonic functions, they cannot, however, be separated from each other. It was mentioned above that the minor is inferior to the major not only in lightness of color, but also in stability. This is partly due to the fact that among the Viennese classics the share of the minor in the unstable parts of the form - developments, introductions, connecting parts, pre-events - is higher than in the stable ones (expositional, concluding). But for the realization of the dynamic and conflict-dramatic possibilities of the minor, not only the corresponding non-harmonic conditions are required, but also quite active changes in the harmonic functions themselves. Likewise, the energetic underlining of the tonic at the end of a work is capable of not only affirming stability and completeness, but also - even with a minor tonic - embody the feeling of victory, the taming of the elements, the triumph of the human spirit, etc.

2) Possibilities of enlarging functional relations in harmony (on the example of comparative analysis of typical turnovers of TD-TD, TD-DT)

But the real basis and at the same time the pearl of all this wealth is, of course, functionality in the narrow sense of the word. Three functions - one tonic, stable and two qualitatively different unstable, dominant and subdominant, each of which (especially the second) has different degrees and forms of expression - create the possibility of changes in stability and instability at very different levels and allow a single current of harmonic voltage to cover huge musical time periods, up to large pieces.

The formula tonic-dominant-dominant-tonic (TDDT) can underlie both the two-bar and the eight-bar period, and the whole old sonata form, and the gravitation of the dominant to the tonic is felt, albeit in different ways, in all cases. In the same way, the cadence formula of three chords - subdominant-dominant-tonic (SDT) - can grow to a sequence of three large constructions at the corresponding organ points, and to juxtaposition of three keys on very different scales, and a single current of harmonic or tonal voltage holds all the sections together. into one whole.

After setting out and explaining the general provisions, it is appropriate to delve into the relationship between harmonic functions and thematic in more detail and using a specific example. We are not talking about the phonic effects of harmony, depending on the register, wide or close arrangement, hardness or softness of the sound, not about the coloristic effects of changing major and minor and not about the expressiveness of especially expressive, characteristic harmonies, but about the emotional impact of "ordinary" tonics and dominants dominating in countless themes of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, Glinka, Tchaikovsky and other classics. Consider the beginning of Mozart's Jupiter Symphony. Here, two contrasting motives are compared - the first on tonic, the second mainly on dominant harmony, after which these motives are repeated in the same order, but exchanging their harmonic functions. A typical combination of thematic periodicity with harmonic symmetry arises, which also occurs on the scale of the old sonata form: abab - TDDT. Since this exchange of harmonic functions did not change the nature of the contrast of a more decisive and softer motive to any noticeable degree, it is tempting to conclude that harmonic functions do not affect the direct expressiveness of music here, but have only a musical-logical meaning, providing tonal isolation and tonal unity of the eight-beat.

Firstly, harmony cannot play its logical role, bypassing the expressive role altogether, because the feeling of stability and instability, support and gravity, harmonious isolation and openness not only arise in music on the basis of sensory sound effects, but also have an emotional character, representing as if a specific kind of musical expressiveness. Secondly, although the contrast of two motives is actively formed here not by harmony, but by other means - dynamics, texture, timbre-register ratios, melodic patterns, rhythm, meter - harmony does not remain completely indifferent to it: each harmonic function has different expressive capabilities. and, as it were, allows the motive sounding along with it to extract from it exactly the opportunity that corresponds to the nature of the given motive.

Finally, the third and main circumstance is that two contrasting motives have not only those features that distinguish them from each other, but also expressive properties common to both motives that unite them. These properties are in the active, joyful, light character of the music; they are realized by means of a major scale, a fast tempo, an active bipartite metric pulsation, which has a great emotional and tonic significance. Harmonic functions are also included in the same circle of means: a clear comparison of tonic stability with dominant instability gravitating towards it; the juxtaposition, which determines a single voltage current from the starting point to the ending point, creates here a similar feeling of joyful energy.

3) Dialectics of tonal-thematic relationships in sonata form

If in the sphere of expressiveness, the functional side of harmony is precisely included in the circle of other equally important means, then as a factor of shaping, movement of a form, its turns, its general logic, especially in a more or less close-up view, it surpasses any other element of the musical language. It's about the sonata allegro.

Of the more or less large forms, only it is penetrated from beginning to end by a single and continuous current of intense tonal-harmonic development.

Chapter 4. The problem of correlation between the functionality of chords and their phonism. Get additional material from p. 254. Linking chord functionality to voice guidance. "Melodic" and "Harmonic" Approaches to Explaining the Major Scale

1) The problem of the relationship between the functionality of chords and their phonism

The concept of phonism of chords, which depends primarily on their interval composition (but also on the number of tones, their active doubling, location, register, loudness), was introduced by Yu. N. Tyulin in his "Doctrine of Harmony" (1937). Yu. N. Tyulin calls the phonism of the chord colorfulness, in contrast to the "modal function". And although in the third edition of the book some clarifying differentiation of the concepts of phonism and color is given, usually these concepts are used by Yu. N. Tyulin as more or less equal in rights.

In "the ratio of phonic and modal functions" Yu. N. Tyulin emphasizes some kind of inverse relationship: "... the more neutral the chord is in the modal-functional relation, the brighter its colorful function is revealed, and vice versa: the ladofunctional activity neutralizes its colorful function."

The phonism of the chord itself, in turn, is also not entirely homogeneous. It includes not only the interval composition of the chord (in its direct acoustic-psychological influence), but also the timbre and loudness. These last elements could even be ranked among the most "pure" carriers of phonism, since, unlike the interval composition of the chord, they do not evoke modal associations. But on the other hand, they are not specific to harmony, they represent independent elements of music. The specific side of phonism in the narrow sense, as a phenomenon related precisely to the field of harmony, is still the interval-sound composition of the chord, including the number of tones, their arrangement, octave doublings.

The phonic (in the narrow sense) side of harmony is of great musical and expressive significance and should be taken into account when analyzing both individual works and the style of various composers. It is known, for example, the special effect of softness and fullness of sound, which Chopin achieved by a certain arrangement of chords on the piano - an arrangement that closely corresponded to the overtone row. This effect belongs to the number of phonic ones proper. It is also known that Beethoven sometimes resorted to such harsh sounds that Haydn and Mozart did not have. Sometimes this manifests itself in the very interval composition of the chord: this is the famous chord in the finale of the Ninth Symphony a few measures before the first introduction of the voice (all seven tones of the harmonic minor scale simultaneously sound in the chord). No less interesting, however, are the cases when typical Beethoven phonism makes itself felt when using the simplest harmonies - major and minor triads. For example, the first chord of the Pathetique Sonata is especially impressive due to the f and the close arrangement of the seven minor triad tones in the low register of the piano (the exact same chord suddenly appears after several measures pp - in the 22nd measure of the earlier Beethoven Sonata in C minor, op.10 no. one). For the style of Haydn's and Mozart's clavier sonatas, this kind of phonism is not typical.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the role of harmonic brilliance in European music, and in particular phonism in a narrow sense, increased. The value of timbre-textured and dynamic effects also increased. In the middle of the 20th century, even a special direction of music emerged - sonoristics, in which sounds as such, and not their harmonic meaning or interval-melodic connections, are highlighted. This direction can be viewed as a one-sided and ultimate development of the phonic side that precedes music. Now it is still difficult to judge its prospects, in particular, whether it is capable of being a more or less independent branch of art, or whether it will be included in the evolutionary process, which more obviously develops the common centuries-old traditions of musical culture.

Now about the two sides of harmony in a completely different sense: harmony as a result of the movement of voices and as a sequence of integral chord complexes. Since the laws of classical harmony were formed, these two aspects of it - intonational-melodic and actually chordal - are equally important and, in principle, are inseparable from each other. The intonationally melodic side associated with vocalism is characterized, in particular, by the gravitation of unstable sounds predominantly towards tones adjacent in pitch. The chord side is manifested in the fact that individual harmonies, although their sequences are subordinated to certain norms of voice-leading, also appear as a certain unity, as relatively independent entities with their own structural laws. At the same time, the ladotonal system of chord connections, which also has its own internal logic, is based not only on the second-second relationships in melodic voices, but primarily on the acoustic quarto-fifth relationship of the main tones of the chord.

How deep the interpenetration of the two sides of harmony is, can be seen at least from the great role that the quarto-fifth combination of chords, especially triads, has acquired in classical music. This role is determined not only by the acoustic kinship of the main tones, as one might think if we stand on a purely "chord" point of view, but also by the optimality of intonation-melodic ratios: the triads have one common tone, and the rest of the melodic voices move smoothly (at the second however, the combination of triads does not have a single common tone, and in the case of the third, there are two of them within the diatonic range, i.e. the amount of melodic movement turns out to be minimal and the connection is perceived as somewhat passive).

In theoretical musicology, the two sides of harmony were only recently clearly recognized in their difference and unity, in their diverse relationships. In the past, theoretical concepts and textbooks of harmony actually focused on one of the sides, and if sometimes spontaneously they took into account both, then without stating the very fact of the existence of both of them.

Similar documents

Harmony in the surrounding world and its philosophical and aesthetic concept, the idea of the consistency of the whole and parts, of beauty. The role of harmony in music, specific ideas about harmony as a pitch harmony. Chords, consonances and dissonances.

abstract, added 12/31/2009

The study of the musical category of romantic harmony and the general characteristics of the harmonic language of A.E. Scriabin. Analysis of the logic of the harmonic content of Scriabin's preludes on the example of the e-minor prelude (op.11). Scriabin's own chords in the history of music.

term paper, added 12/28/2010

The physical basis of sound. Properties of musical sound. Designation of sounds by the letter system. Definition of a melody as a sequence of sounds, as a rule, in a special way associated with a mode. The doctrine of harmony. Musical instruments and their classification.

abstract, added 01/14/2010

N.K. Medtner as one of the brightest composers at the turn of the XIX-XX centuries, an assessment of his contribution to the development of musical art. Revealing the stylistic features of harmony as a means of outlining musical images. Study of the relationship between diatonic and chromatic.

report added on 10/22/2014

Analysis of the formative means of musical harmony. Signs of a classical chord as a whole unit of pitch fabric. The use of harmonic color for solving the visual problems of music. Schumann's Harmonic Language in the Carnival Cycle.

term paper, added 08/20/2013

The meaning of the soloist's pauses, filled with performances by the orchestra (musician). An example of the simplest blues scheme in C major. Negro singing style. Blues pentatonic scale and harmony. Repeat a melodic line. Rhythmic design of harmony accompaniment.

abstract, added 12/12/2013

Intonation. The evolution of European harmony from the 17th to the 19th century The life of a piece of music. Timbre and intonation formation of music in Europe. Overcoming inertia with music. Oral music. Renaissance and the era of rationalistic thinking. Reger's phenomenon.

term paper, added 06/18/2008

Basic principles of jazz harmony. Alphanumeric and step designation of chords, their composition. Presentation of the melody in the chord texture. Basic chords of tonic, dominant and ubdominant functions. The specifics of the arrangement of chords in jazz.

term paper, added 01/16/2012

The study of the epic-dramatic genre in the works of F. Chopin on the example of Ballad No. 2, op.38. Analysis of the drama of a ballad, the study of its compositional structure. The use of elements of the musical language: melody, harmony, chord, metro rhythm, texture.

term paper, added 07/06/2014

Study of the genesis of philosophical and musical concepts (socio-anthropological aspect). Consideration of the essence of musical art from the point of view of abstract logical thinking. Analysis of the role of musical art in the spiritual formation of the individual.

Harmony in the world around

What do we usually mean by the word "harmony"? What phenomena around us are characterized by this word? We are talking about the harmony of the universe, meaning the beauty and perfection of the world (the field of scientific, natural and philosophical); we use the word "harmony" in connection with a person's personality (harmonious nature), characterizing his spiritual inner integrity (ethical and psychological area); and finally, we call a work of art harmonious - poetry, prose, paintings, films, etc. - if we feel natural in them. harmony, harmony (this is an artistic and aesthetic area).

The philosophical and aesthetic concept of harmony has been developed since ancient times. Among the Greeks, it was reflected in the myths about space and chaos, about Harmony. In the V - IV centuries. BC NS. the first evidence of the use of the word "harmony" in a special musical-theoretical sense is also noted. Philolaus and Plato call "harmony" an octave scale (a kind of octave), which was thought of as the concatenation of a fourth and a fifth. Aristoxenus calls one of the three - enharmonic - genera of melos "harmony".

In all these different areas with the word "harmony" we get the idea of the consistency of the whole and the parts, beauty, in short - that reasonable proportionality of the beginnings ", which is the basis of all that is perfect in life and art. Music is no exception here: accordion, harmony in a broad artistic and aesthetic sense characterizes every significant piece of music, the author's style.

The role of harmony in music

Since ancient times, the harmony of music has been associated with the harmony of the cosmos, and, as the philosopher I.A. Gerasimov, music also carried a certain philosophical meaning. only one who was in tune with the cosmic tone through his music could be considered a true musician

The question of why exactly music was considered as something denoting the connection between the earthly and heavenly, cosmic order and the earthly world, requires an appeal to the concept of harmony. The very concept of harmony requires some additional decoding in this connection. Despite the fact that harmony from a technical point of view is traditionally associated primarily with music, the concept itself is much broader. When mentioning the harmony of the world, we mean its order and a certain perfect structure, a structure characterized primarily by its spatial arrangement. Thus, the concept of harmony extends to spatial figures. This is evident from the numerous references to architectural harmony. The reversibility of the concept of harmony also reflects the characteristic of architecture as non-sounding, frozen music. For all the metaphorical nature of these definitions, they reflect a completely recognizable and specific combination and substitution of spatial and temporal characteristics. The geometric perception of sound is known, for example, contained in an ornament, characteristic of the Ancient East, or Pythagorean geometric images of harmonic sounds, which is only an illustration of the stability of the noted connection.

Music is a special type of modeling of the world, where it is viewed as a perfect system. The latter sets it apart from other ideas about the myth. Music has many meanings, but behind the multiplicity of its meanings lies an invariable framework of musical syntax, described by mathematical structures. Already in this duality, music is similar at the same time to the world and to science, speaking in the clear language of mathematics, but trying to embrace the diversity of the changing world.

Musical harmony is one of the most well-organized phenomena. The abstractness of sound needs an over-concentrated logic - otherwise music would not say anything to people. One look at modal and tonal systems, for example, can reveal to scientists from different fields possible models of harmonious organization, where instincts and aspirations of tones, permeated with the human creative spirit, are born in an infinite acoustic environment.

The ability of musical art to predict the greatest achievements of scientific thought is amazing. But no less amazing is the ability of musical theory: appearing with a natural delay, it steps steadily on its row on the basis of predicted scientific booms in order to master them in expanded musical theoretical systems

The concept of harmony in music dates back about 2500 years. The traditional concept of harmony for us (and the corresponding interpretation of the most important compositional and technical discipline) as the science of chords in the major-minor tonal system was formed mainly by the beginning of the 18th century.

Let's turn to ancient Greek mythology. Harmony was the daughter of Ares - the god of war and strife and Aphrodite - the goddess of love and beauty. That is why the combination of insidious and destructive power and the all-embracing power of eternal youth, life and love - this is the basis of balance and peace, personified by Harmony. And harmony in music almost never appears in its finished form, but, on the contrary, is achieved in development, struggle, formation.

The Pythagoreans very deeply and with infinite persistence understood musical harmony as a consonance, and consonance - necessarily as a fourth, fifth and octave in comparison with the fundamental tone. Some people also declared duodecimus as consonance, that is, a combination of an octave and a fifth, or even two octaves. Basically, however, it was the fourth, fifth and octave that figured everywhere, first of all, as consonances. This was the inexorable demand of the ancient ear, which clearly and very stubbornly, first of all, considered the fourth, fifth and octave to be consonants, and we must reckon with this demand as an irrefutable historical fact.

Subsequently, the concept of harmony retained its semantic basis ("logos"), however, specific ideas about harmony as pitch harmony were dictated by evaluative criteria that were relevant for this historical era of music. With the development of polyphonic music, harmony was divided into “simple” (monophonic) and “composite” (polyphonic; in the treatise of the English theoretician W. Odington “The Sum of Music Theory”, early XIV century); later, harmony began to be interpreted as the doctrine of chords and their connections (G. Tsarlino, 1558, - the theory of the chord, major and minor, major or minority of all modes; M. Mersenne, 1636-1637, - the ideas of world harmony, the role of bass as the foundation of harmony, the discovery of the phenomenon of overtones in the composition of musical sound).

Sound in music is the initial element, the core from which a piece of music is born. But the arbitrary order of sounds cannot be called a work of art, that is, the presence of the original elements is not beauty. Music, real music, begins only when its sounds are organized according to the laws of harmony - natural laws of nature to which a piece of music inevitably obeys. I want to note that this art is important not only in music, but also in any other area. Having learned harmony, you can easily apply it both in ordinary life and in magical life.

The presence of harmony is felt in any piece. In its highest, harmonious manifestations, it acts as a continuously flowing light, in which, undoubtedly, there is a reflection of unearthly, divine harmony. The flow of music bears the stamp of sublime peace and balance. This does not mean, of course, that there is no dramatic development in them, the hot pulse of life is not felt. In music, in general, absolutely serene states rarely arise.

The science of harmony in the new sense of the word, as the science of chords and their successions, essentially begins with the theoretical works of Rameau.

In the works of Rameau, a tendency towards a natural-scientific explanation of musical phenomena is clearly traced. He seeks to deduce the laws of music from a single, nature-given foundation. This turns out to be a "sounding body" - a sound that includes a number of partial tones. “There is nothing more natural,” writes Rameau, “than that which directly comes from tone” ”(136, p. 64). Ramo recognizes the principle of harmony as the fundamental sound (fundamental bass) from which intervals and chords are derived. He also determines the connections of consonances in harmony, the relationship of tonalities. The chord is thought by Rameau as an acoustic and functional unity. He deduces the main, normative for his time consonant triads from three intervals, enclosed in a series of overtones: pure fifth, major and minor thirds. The reference fifth interval can be divided in various ways into two thirds, which gives a major and minor triads, and thus two frets - a major and a minor (134, p. 33). Ramo recognizes that the main chord is built in thirds. Others are seen as his conversion. This introduced an unprecedented order in the understanding of harmonic phenomena. From the so-called triple proportion, Rameau deduces the fifth ratios of the three triads. He revealed, in essence, the functional nature of harmonic connections, classified harmonic sequences and cadences. He found that the process of musical development is managed harmoniously.

Having correctly grasped the dependence of melody on harmonic logic, which is really characteristic of classical music, Rameau unilaterally absolutized this position, not wanting to notice and take into account in his theory the dynamic role of melody, which alone could endow the classically balanced model of harmony proposed by him with genuine movement. It was precisely in the one-sidedness of Rameau, who faced the no less one-sided position of J.-J. Rousseau, who asserted the primacy of melody, is the cause of the famous dispute between Rameau and Rousseau.

Musical theory operates with the word "harmony" in a strictly defined sense.

Harmony is understood as one of the main aspects of the musical language associated with the unification of sounds in simultaneity (so to speak, with a vertical "cut" of the musical fabric), and the unification of consonances with each other (horizontal "cut"). Harmony is a complex area of musical expressiveness, it unites many elements of musical speech - melody, rhythm, governs the laws of the development of a work.

In order to form an initial, most general idea of harmony, let's start with a concrete example, recalling the theme of Grieg's play "Homesickness". Let us listen to it, paying special attention to the consonances that make up the accompaniment.

First of all, we will notice that all the consonances are different: both in their composition (in some - three different sounds, in others - four), and in the sound quality, the impression produced - from a soft, rather calm (first), “durable », Stable (second, last) to the most intense, unstable (third, sixth, seventh) with a large number of intermediate shades between them. Such different accords give a rich coloring to the melodic voice, giving it such emotional nuances that it does not possess on its own.

We will find further that the accords, although separated by pauses, are closely interconnected with each other, some naturally pass into others. Any arbitrary permutation will break this connection, break the natural sound of the music.

Let's pay attention to one more feature of harmony in this example. The unaccompanied melody breaks down into four separate phrases, their similarity serving to dismember the melody. And the accompaniment, built on different consonances, moreover consistently connected with each other, as if arising from one another, masks this similarity, removes the effect of "literal" repetition, and as a result, we perceive the whole theme as a single, renewing and developing one. Finally, only in the unity of the melody and accompaniment do we get a clear idea of the completeness of the theme: after a series of rather tense chords, a more calm final one creates a feeling of the end of the musical thought. Moreover, this sensation is much more distinct and weighty in comparison with the sensation that produces the ending of only one melody.

Thus, in this one example, it is obvious how diverse and essential the role of harmony in a piece of music is. From our brief analysis it is clear that two sides are equally important in harmony - the arising sound combinations and their connection with each other.

So, harmony is a certain system of vertical combinations of sounds in consonance and a system of communication of these consonances with each other.

The term "harmony" in relation to music originated in ancient Greece and meant a certain ratio of sounds. And since the music of those times was monophonic, these regular relationships were derived from the melody - from the succession of sounds one after another (that is, in terms of melodic intervals). Over time, the concept of harmony has changed. This happened with the development of polyphony, with the appearance of not one, but several voices, when the question arose about their consistency in simultaneous sounding.

Music of the XX century. developed a slightly different concept of harmony, which is associated with considerable difficulties in its theoretical understanding and which, accordingly, constitutes one of the most important special problems of the modern doctrine of harmony.

At the same time, the perception of a particular chord as harmony (that is, consonance) or as a set of unrelated sounds depends on the listener's musical experience. Thus, to an unprepared listener, the harmony of 20th century music may seem like a chaotic set of sounds taken in simultaneity.

Let's get to know more closely the means of harmony, considering first the properties of individual consonances, and then the logic of their combinations.

Dmitry Nizyaev

The classical harmony course is based on a strictly four-part texture, and this has a deep rationale. The fact is that all music as a whole - both texture, and form, and the laws of melody construction, and all imaginable means of emotional coloring - comes from the laws of human speech, its intonations. Everything in music is from a human voice. And human voices are divided - almost unconditionally - into four registers in height. These are soprano, alto (or "mezzo" in vocal terminology), tenor and bass. All the innumerable varieties of human timbres are just special cases of these four groups. There are simply male and female timbres, and there are highs and lows among both - here are four groups. And, strange as it may seem, four voices - different voices - this is exactly the optimal amount required to sound all the harmonies existing in harmony. Coincidence? God knows ... One way or another, let's take it for granted: Four voices are the basis.

Any texture, no matter how complicated and cumbersome you create it, will in fact be a four-part, all other voices will inevitably duplicate the roles of the main four. Interesting note: the timbres of the instruments also perfectly fit into the four-part scheme. Even the ranges of notes available to them are practically the same as the ranges of human voices. Namely, in the string group: the role of the soprano is played by the violin, the mezzo - by the alto, the tenor - by the cello, the bass - by the contrabass, of course. In the group of woodwind, in the same order are: flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon. For copper: trumpet, French horn, trombone, tuba. I am listing all this for a reason. You can now safely replace the timbres of one group with another, without worrying about the pitch range, without rewriting the melodies. You can easily transfer music for a string quartet to the same quartet of wind instruments, and at the same time the music will not suffer, since the roles of the voices, the structures of their melodies, technical limitations, emotional colors - correspond to each other in the same way as in human voices.

So, the first rule: we will do everything in four voices. Secondly, since we do not pursue the goals of arrangement, but only study the interaction of consonances (as mathematics does not mean physical apples or boxes by numbers, but operates with numbers in general), we do not need any tools. Rather, anyone who can produce four notes at the same time will do, the default being a piano. In addition, for the sake of purity and transparency of our thinking, we will write examples and exercises in the so-called "harmonic" texture, that is, vertical "pillars", chords. Well, except that occasionally it will be possible to give a more developed textured example to show that the law under study is valid even in such conditions. Rule three: exercises or illustrations in harmony are written on the piano (i.e. double) stave, and the voices are equally distributed along the lines: on the top - soprano and alto, on the bottom - tenor and bass. The spelling of calmness in these conditions differs from the traditional one: regardless of the position of the note head, the calmness is always directed upwards for the soprano and tenor, and always downwards for the rest. So that the voices in your eyes are not confused. Fourth: if we need to name a polyphonic consonance with words, the notes are listed from bottom to top, indicating the sign (even if it is in the key), okay? Fifth - this is VERY important - never substitute, say, C sharp D flat in harmony, even though it's the same key. Firstly, these notes do have different meanings (they belong to different tonalities, have different gravitation, etc.), and secondly, despite the generally accepted opinion, they actually have even different pitches! If we talk about the tempered and natural tuning (I don’t know yet if this will happen), then you will see that C sharp and D flat are completely different notes, nothing in common. So let's agree for now: such a substitution of one sign for another can happen only "for a reason", and not at will. This is called "anharmonicity" - we will have such a topic yet to come. Well, let's get started with a prayer ...

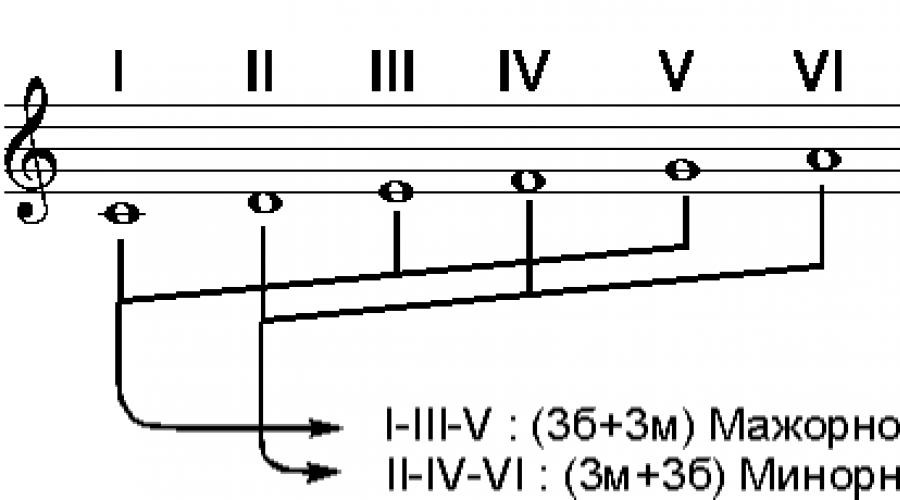

STEPS

All the patterns studied by harmony are absolutely exactly repeated in any key, they simply do not depend on the name of the tonic. Therefore, in order to express this or that consideration, suitable for any key, we cannot use the names of the notes. For convenience, the scale of any key is supplied with numbers that replace the names of the notes, and these conditional numbers are called steps. That is, the very first, main sound of the scale - it does not matter what kind of note it is, and what kind of harmony it is - becomes the first step, then the count goes up to the seventh step (in C major, for example, it is "B"), after which it follows again the first one. The step numbers will be represented by Roman numerals "I - VII". And if we find that, for example, between D and F (II and IV degrees of C major) there is an interval of a minor third, then you can be sure that the same interval will turn out to be between II and IV degrees of any major, whatever the impossible signs there nor were they at the key. Convenient, isn't it?

SOUND

We already know that a triad is a combination of three notes arranged in thirds. To make you feel at ease among triads, I advise you to practice building triads from arbitrary notes both up and down. Moreover, it would be nice to be able to do it just instantly, combining three ways: to press them on the keys (even on imaginary ones), sing them in order to memorize their color by heart, and sing them silently, in the imagination. This is how the "inner ear" is brought up, which will help you to have sounding music right in your head, to continue working right on the street, and in addition will give you the opportunity to "lead", "sing", track several melodic lines in your mind at once (after all, with your voice you won't cover more than one melody at a time!).

You've already been told that there are four types of triads: major, minor, increased and decreased. But these are only words, names. But are these words associated in your mind with color? What emotions does the word "reduced" evoke in you? Here the inner ear is at your service, and you feel a relative "minority" (due to the abundance of ma-a-a-lil thirds) and a cutting "lively" dissonance (reduced fifth). The result is a sad, aching, full of pain, and at the same time smelling of oriental exoticism. You were also told what a fret is. We already know that if we “select” for work among absolutely identical semitones several, located in a certain way on the keyboard, then the concept of tonic appears, gravitation appears, in a word, unequal relationships between the selected notes. The fret is the whole set of gravities, the stability of a particular set of sounds. Let us now introduce a new term - "diatonic". It is something like a coordinate system within which all events take place. That is, we are dealing with only seven keys out of twelve in each octave, and the other five do not seem to exist for us. These seven keys are the diatonic scale, the diatonic scale, the current coordinate system for the key and scale data, is that clear? Any sound that does not belong to this scale is considered not "diatonic", but "chromatic" (in a given key). And now let's get back to our triads. From the theory lessons, you know that a major triad consists of a major and a minor third, right? But this is out of tonality. But within the diatonic scale of the same C major, the combination of the degrees of the scale and their gravities comes to the fore, while the intervals between them lose all interest. For example, the major triad from the note "F" really consists of major (fe-la) and minor (la-do) thirds, and this does not mean anything, this is a faceless and uncolored definition. And if we press the "fa - do - la" triad, then it will be composed of a fifth and a sixth, and will not fit this definition! But in terms of the tonality of C major, our triad takes on meaning: it is a subdominant triad, regardless of the location of the notes inside it. The characters and desires of each note become noticeable in it.

"Fa" is quite firmly on its feet, but does not mind going to "mi". Because "fa" is the prima, the main sound of the chord, and if it is resolved in "e", it will become just the third of a new chord - and it is more pleasant for anyone to be the first guy in the village than to be a small fry in the city! "La" is an unstable and indecisive sound, although it smiles. Judge for yourself: "la" is not a leader here either, and after permission it does not shine anything better than being the farthest from the tonic. However, "la" is still a major, large third, therefore it exudes optimism. "Before" is another matter entirely. She is above everyone else, she is on the right track, she has to become a queen (that is, a tonic) and at the same time she will not have to move a finger. "Do" will remain in its place, and honor and respect will come to it themselves. Here is the event "fa-la-do ... mi-sol-do", containing many emotions and adventures at once. You might guess that in conditions of a different key, when the F major triad is on a different level, each note of it will have completely different colors and emotions, gravitate in a different way. Let's make the following conclusion - it's not enough to find out how this or that chord is built! The most interesting thing with this chord will only happen in the key. And from the point of view of harmony, any triad should be called not major or minor - this is not the main thing now - but the triad of one or another degree, or one or another functional group. Moreover, it can be built not only by thirds, do you agree?

Now let's just trace which triads we have in major and minor. I don’t think it should be memorized, it will be remembered gradually by itself; just follow through. To do this, take a natural (that is, the main, unchanged) major scale, and measure the triad from each of its degrees. We should not care whether big thirds or small thirds are obtained, we should only measure the steps through one, remaining in this diatonic, okay?

Etc. Having built everything that is possible, we will get the following list for the major: I degree-major; II - minor; III - minor; IV - major; V - major; VI - minor; VII - reduced. And for a minor: I degree - minor; II - reduced; III - major; IV - minor; V - minor; VI - major; VII - major.

To summarize: in both frets, the triads of the main steps (I, IV, V) coincide with the main mode. Median and submedian (III, VI) have the opposite mode. The triads of the introductory steps (these are II and VII, adjacent to the tonic) just need to be remembered, they do not fit into a symmetrical scheme. So that you do not have to return to the question of where and which triads are located in the key, practice:

1. Find the tonic from the triad (for example, the B-flat - D - F triad, major: in what keys can it occur; what is the tonic if this triad is stage VI? Or III? Or IV?).